Chapter 28 Mahakhitan Kaleidoscope (2): Mahakhitan Vexillology, and Brief Introduction to the Country’s Army and Navy

028 – 摩訶契丹旗幟學,兼該國陸海軍簡介

(This is the second piece in the Mahakhitan Kaleidoscope series. I wanted to make some time and carefully draw some more to show my gratitude as the column recently hit more than one thousand followers. Didn’t expect it was done in two weeks with little work each day…)

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

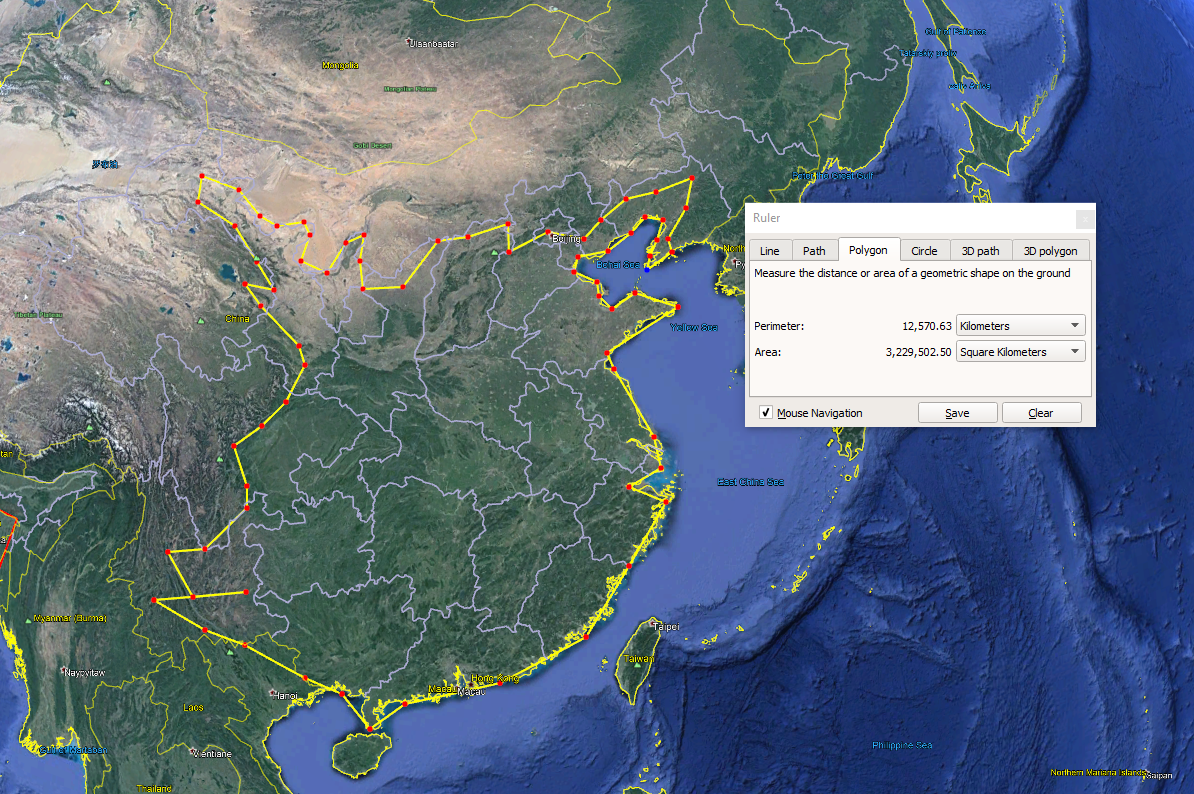

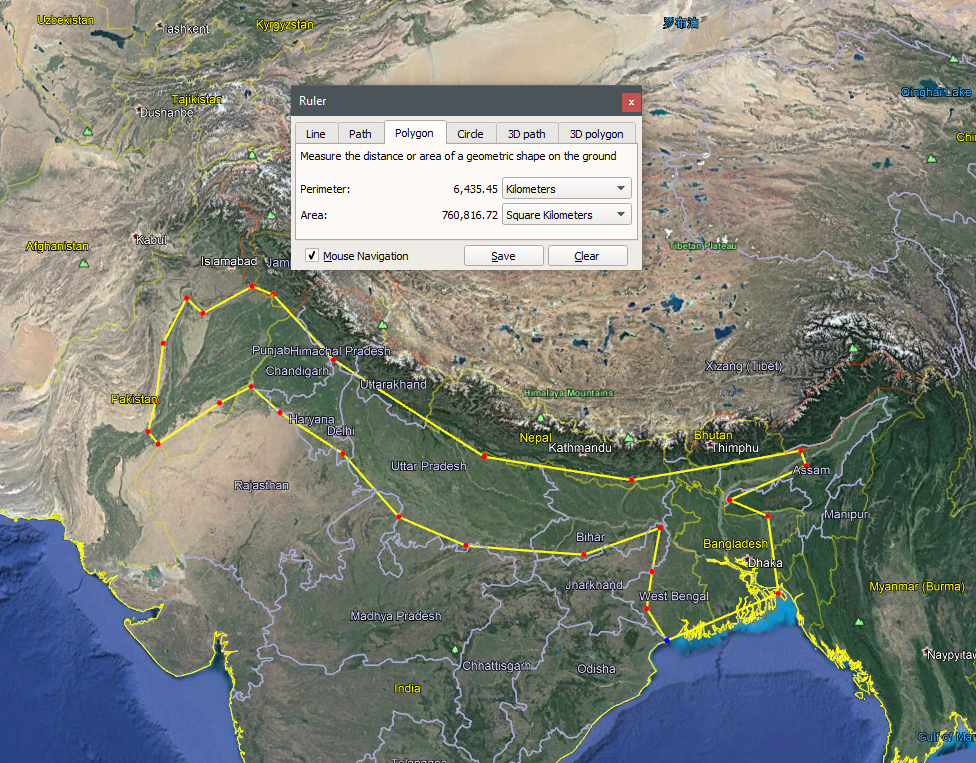

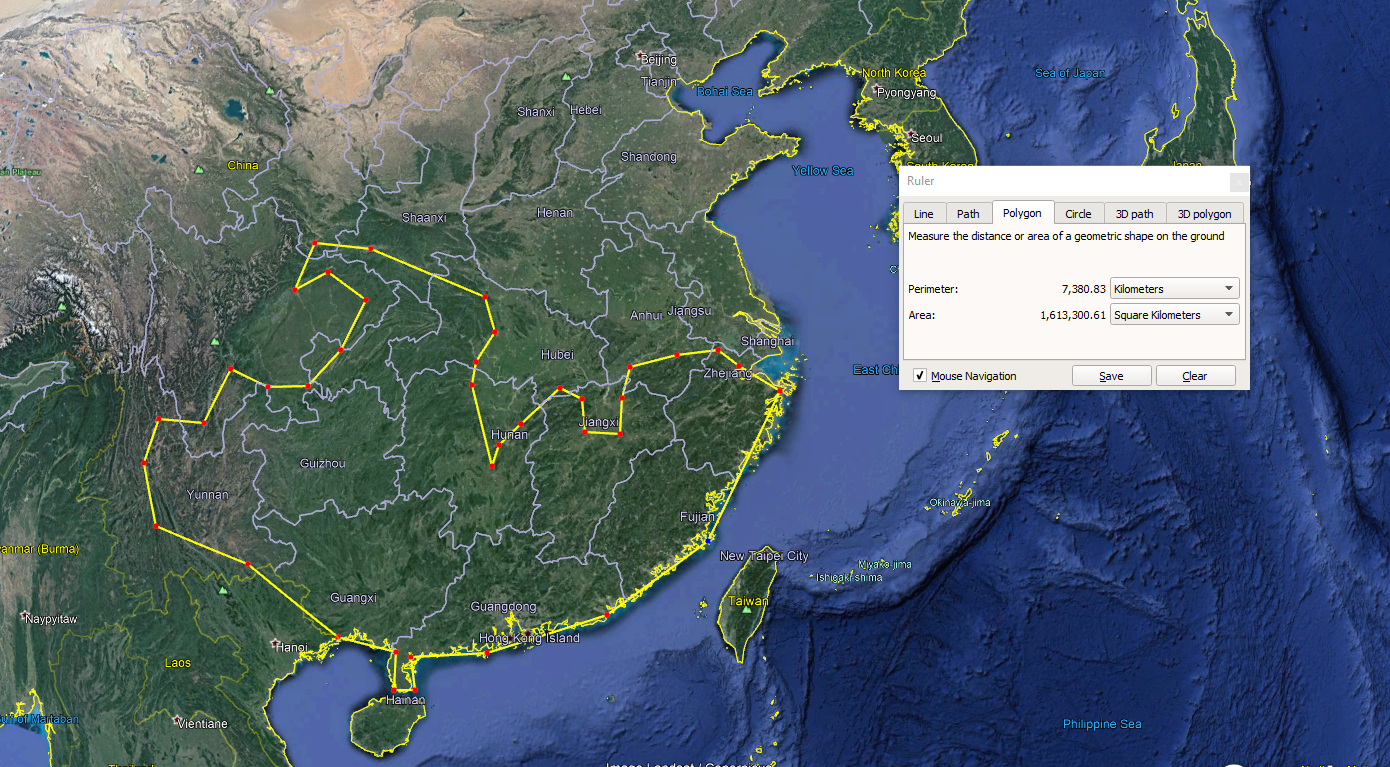

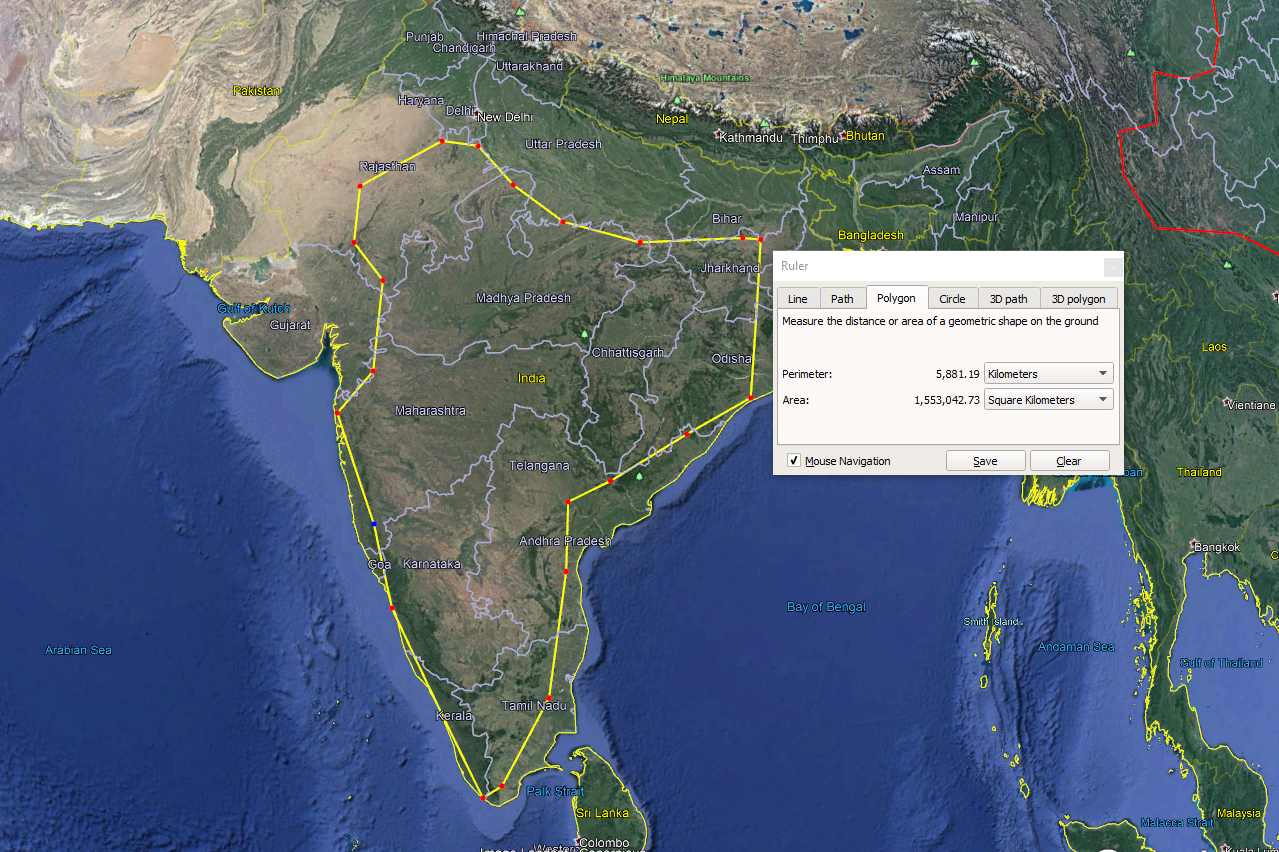

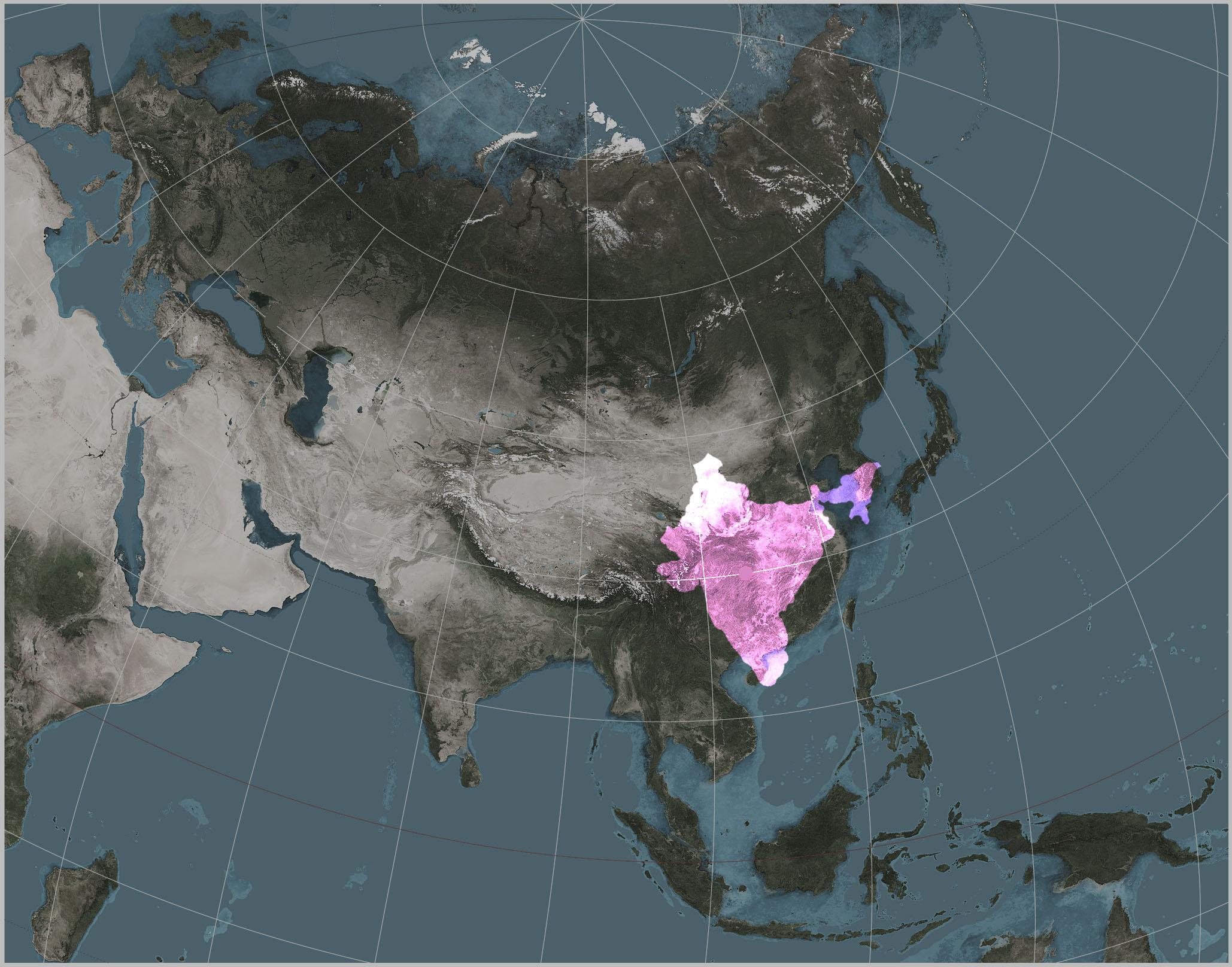

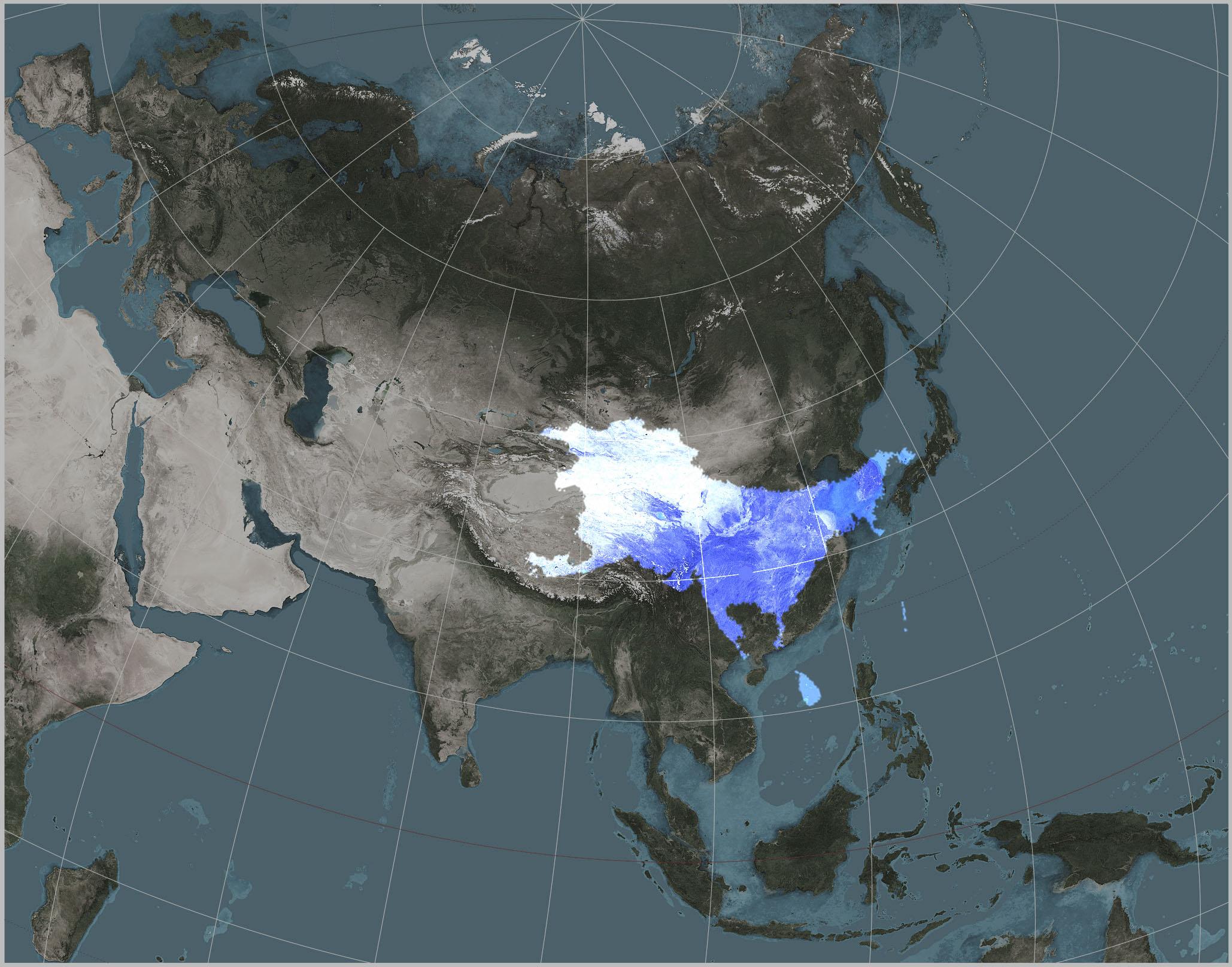

During its frequent interaction with European countries in 17th Century, Mahakhitan gradually formed a system of nationality identification. On the sea, a set of flags are sufficient to clearly show one’s identity, while the army reform following the model of the French Royal Army brought the Liao Army its army flag system. Till around 1700, the flags inherited for several centuries were gradually standardised, and became what we are to talk about today.

The conditions of the army and navy will be mentioned as we proceed.

National Flag?

The flag systems of this era do not necessarily contain the clear concept of national flags we have today. Mahakhitan, for example, divided the concept into two parts – the imperial banner (帝幟) and the public banner (公幟), in accordance with the Royal Standard and State/Government Flag in the west.

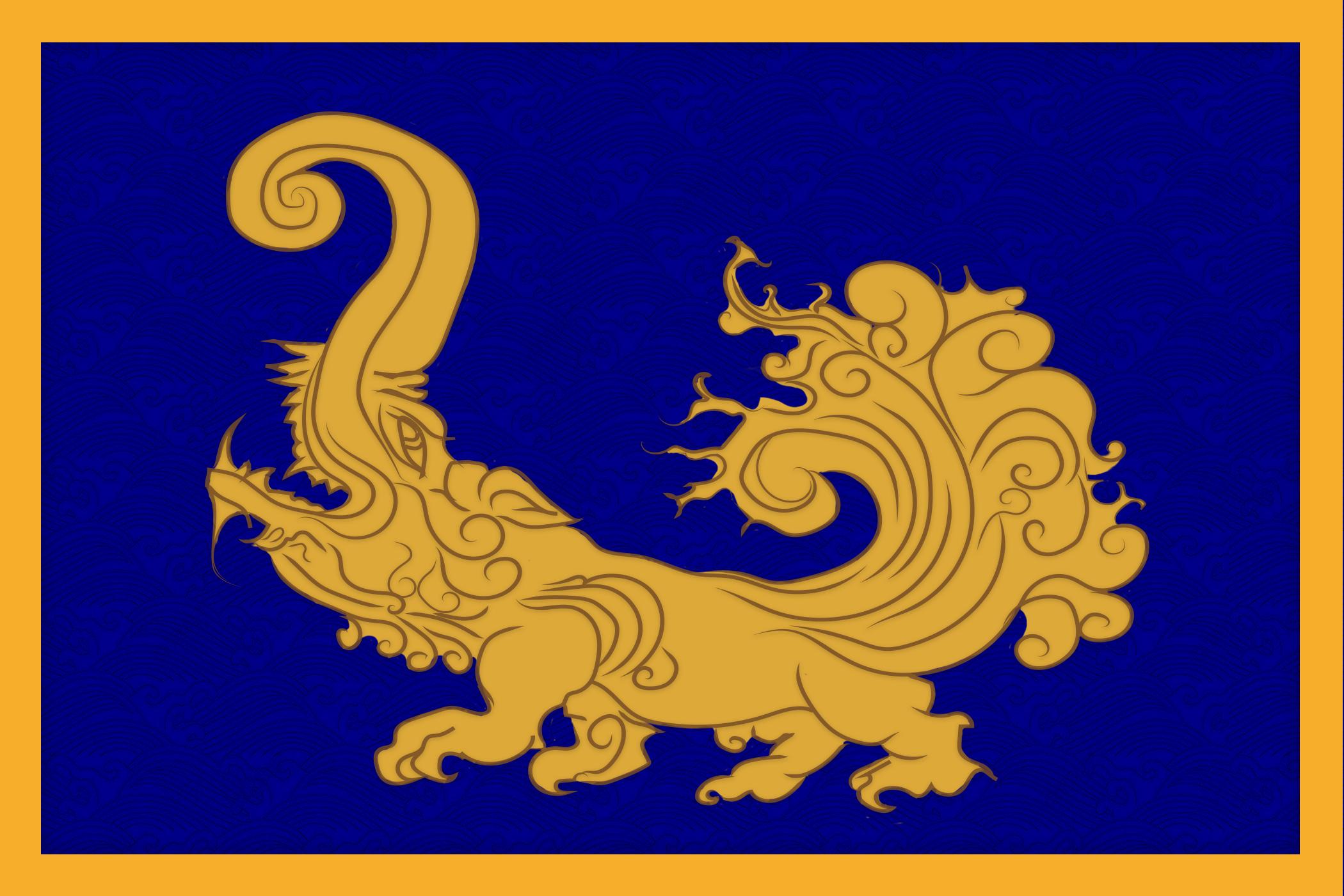

Imperial Banner: Flag of Gyrfalcon in Clouds (雲間海青旗)

The flag that represented the Yelu imperial house, hanged in occasions where imperial family members are present, or in certain scenarios related to some clans that intermarried with the imperial house. The colour black represents the Virtue of Water (水德) of the Yelu house. The pattern is on the other hand the traditional swan-hunting gyrfalcon, which has been around since ancient times, frequently used since mid 16th Century, became the symbol of Khitan aristocrats and eventually narrowed down as the symbol of the imperial house. Quite a number of other Khitan aristocrats’ flags adopted some variant of it, such as the Flag of Moon and Gyrfalcon (月海青旗) of the Xiao (蕭) clan of Hejian and so on.

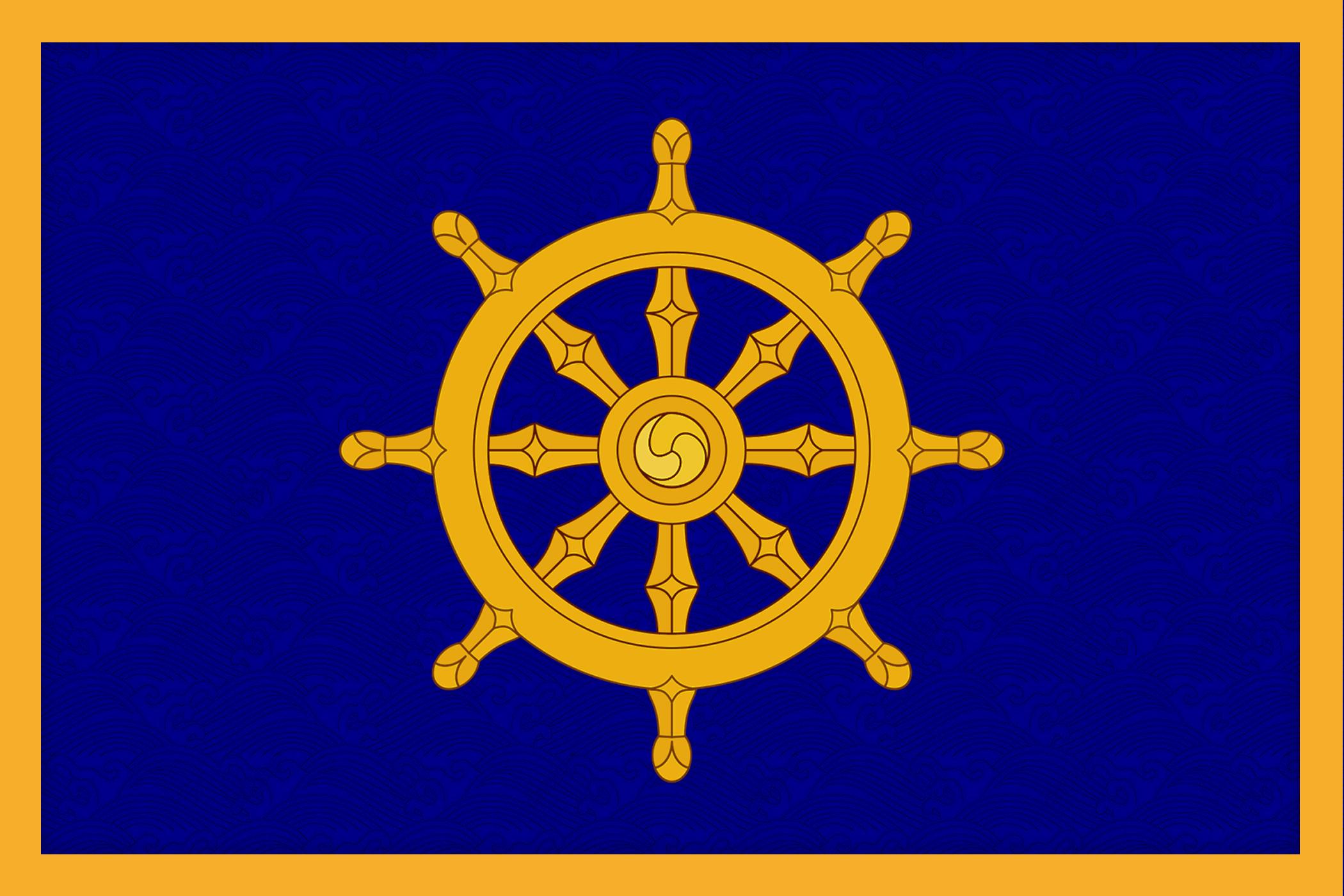

Public Banner: Flag of Dharmachakra (Dharma Wheel) on the Sea (海上寶輪旗)

The flag represents the authority of the imperial Zhongshu Department and the “government body of the sagely dynasty of turning wheel” under it. It has a very long history and carries the same as always meanings: the sea represents the wisdom of the sagely king, the dark blue close to black represents the Virtue of Water of the empire, the Dharmachakra is the symbol of the unstoppable power of the wheel-turning sagely king, and the golden margins carry the connotation of “forever firm and stable the golden cup” (金甌永固

, a metaphor where 金甌/golden cup is used to refer to land of sovereignty). This flag is to be used more and more as the national flag in the future.

The two flags above are both specially square, representing the rule of all four directions (君臨四方), grace for all beings, unbiased and equal.

As for the relationship between them, it can be put this way. The Dharmachakra flag is equivalent to the Union Jack of the United Kingdom, while the gyrfalcon flag is the equivalence of the British Royal Standard that represents the royal house with golden lions, red lion and harp respectively in the four quadrants.

The fabric of the flags – hmm, the shading is legally required on the flags, but usually the commoners still use plain cloth. Flags from the authorities use quality “cloud brocade” (雲錦) and “sea wave brocade” (海波錦) fabrics from the Ghatpot and Brocade Courts (綾錦院

, state-owned textile workshop with the name coming from Song China IOTL) of Nanjing and Gaozhou, thus complementing the full authority the two flags are supposed to carry.

Shanyang, Hanshan and Puti as traditional major feudal territories used to have their own flags, which are now almost completely out of use. The General-Governor’s Office of Videha usually uses a variant flag showing Dharmachakra on red earth with “mountain” patterns (山紋

, which more or less look like geometrical diamond patterns than abstracted “mountain shapes”).

Now about the army:

The army is a proud organisation with long traditions. They always claim their history dates back to Tang Dynasty of Mahachina (摩訶至那), although the oldest existing army unit was formed only in the 15th Century. They customarily use triangular flags commonly seen in South and Southeast Asia, and despite invited French officers brought the French Army’s flag system where troops are identified with colours, the Khitan military academies on the other hand made the decision to only adopt the colour insignia system, and disregarded the square, embroidered, tasseled banners with cross patterns.

So the fused army flags present a mixed, Khitan-foreign outlook – but overall still very traditional, just like the other modernisation effort of this military force. It learned to use bayonets and line infantry tactics, but did not equip fusils or form grenadier units due to the overly expensive cost of imported weaponry. The army also fails to closely follow the military revolution since the 18th Century. The generals however are still fully proud of their history – this is after all an army that swept from East Sea to West Sea.

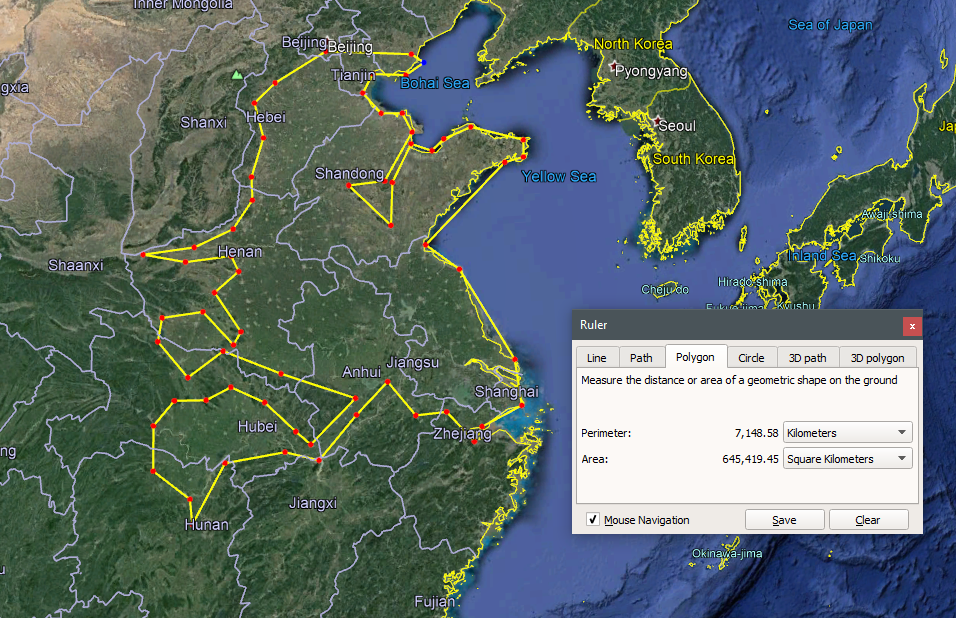

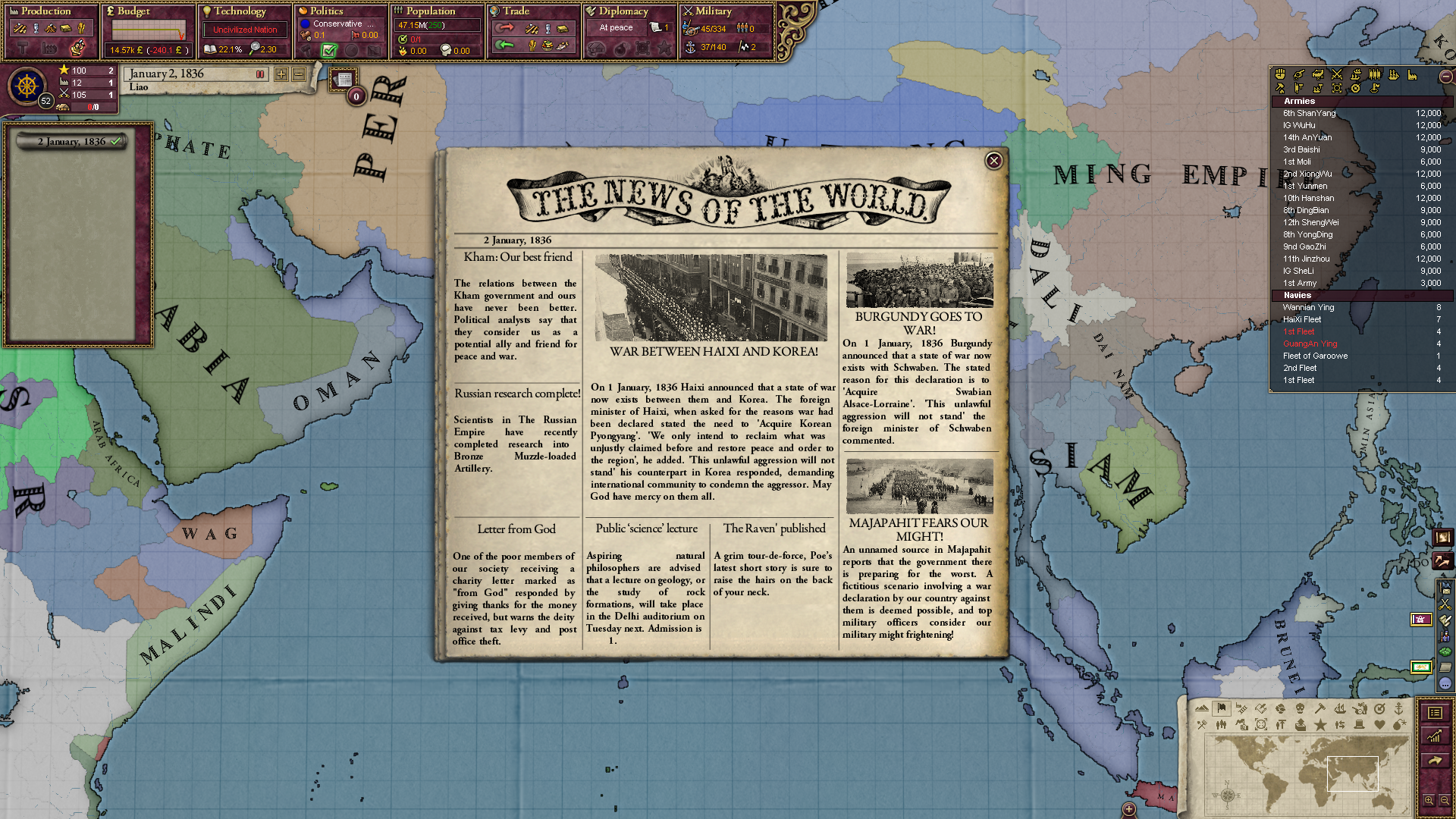

After the military reform of the 1680s following the French model, the Mahakhitan Army has the following chain of command:

Qi (旗/“Flag”) – approximately 3,000-men strong, close to the equivalence of brigades in western armies of the era, containing 3-4 ying (營/“battalions”), and is the largest tactical unit consisting of troops belonging to the same arms. The name “Qi” originated from the units’ military flags, as in each qi has a flag conferred by the emperor, which is to be guarded at all cost by the men under the qi. We shall come back to these flags after we are done with the formations. The wei (衛/“garrison”) as an important army formation of fortification is usually of similar size to the qi, but lacks the honour brought by the conferred imperial military flag.

Further, the Liao army forms every 4-6 qi as one zhen (鎮), equivalent to an army in the west at that time. As many as two zhen can be stationed within a circuit when needed by the empire. The full name of a zhen is the Commanding Agency of ** Zhen (**鎮臺指揮使司), so the chief officer of a zhen is called the commander (指揮使), whereas conventionally people would refer to him as “junzhu” (軍主/“army lord”) or “xiangwen” (詳穩/modern Pinyin transliteration of the Khitan word “general”). He is in charge of managing the regular affairs of military farming and training, where over half of the supplies of each zhen comes from military farming during peace times.

Every few years the officers are rotated to new posts in case of possible warlord-ification, and the various zhen are also often swapped. These complicated deployments (as such movements are often wheel-shaped on maps, they are constantly rumoured to be related to the wheel-turning of the sagely king) are pretty much a fairly large part of the usual work of the Ministry of War/Privy Council.

When wars break out the emperor would order the Office of Generalissimo to dispatch generals and set up the Office of Field Marshal Against ** (征**處元帥府

, where ** is name of the place targeted), and this would be the military commanding institution of the corresponding front during the war. An Office of Field Marshal also generally forms several “jun” (軍/“armies”) to facilitate wartime commanding, with one to three zhen under each jun depending on different circumstances.

Military Banners of the Army: Flags of Vajra-Holding Lion (金剛獅子旗)

Click to expand for details. The grey parts are backgrounds –

*Captions are “Imperial Conferred First Yunmen/Cloud Gate Zhen Front Qi” and “Imperial Conferred Sixth Shanyang Zhen Right Qi”, respectively.

The Vajra is solidified thunderbolt in Hindu legends and the hardest matter in the world; the lion is on the other hand linked to majestic roars and subjugation of all beings. Due to such auspicious allusions, the flag successfully survived among numerous ancient flag designs. The flag itself is still of the traditional, embroidered triangular shape, with the unit designation written on the side attached to the flagstaff. The colour of the flag varies among different qi in each zhen, as the means of distinction within the same zhen.

It is noteworthy that in Hanshan, Jinzhou and Videha the local forces have been kept and nominally also called zhen. The lions on their flags have special, different weapons in in their paws.

For example: the Tenth Hanshan Zhen (Persian shamshir), the Fourteenth Jinzhou Zhen (Malay kris), the Fourth Videha Zhen (barbed spear).

The Liao Imperial Guards on the other hand can use the triangular gyrfalcon flag as their military flag and are envied by the other various zhen.

Then we come to the sea:

For any modern country, the navy is always more progressive and modern than the army, and our Great Liao is no exception.

The Liao Navy, for identification concerns, no longer uses the traditional triangular flags and instead adopted 3:2 rectangular flags similar to those in the west. The flag patterns are in turn quite traditional. It should be noted that out on the sea, official and civilian flags of Liao are very clearly distinguished.

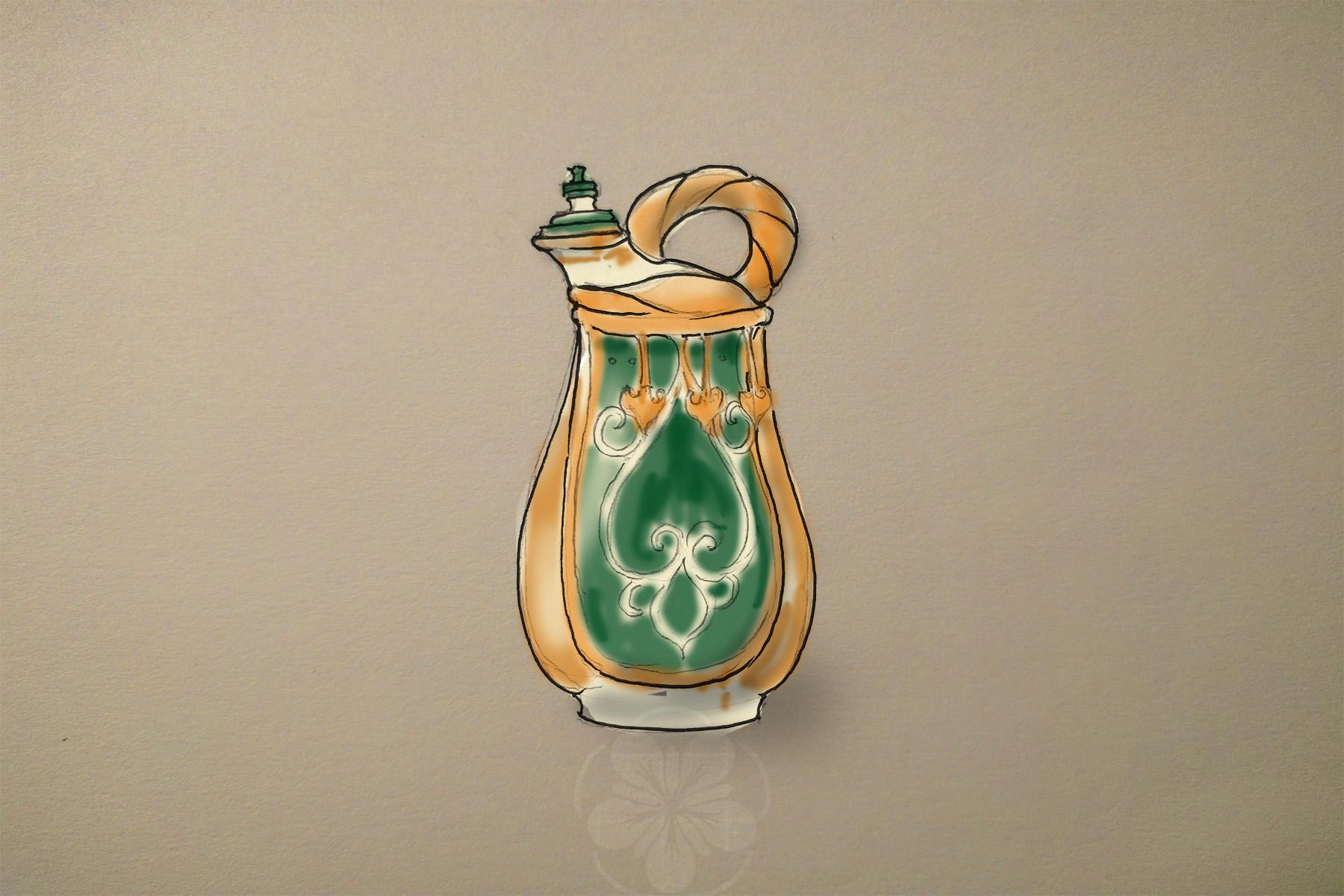

The Liao Naval Banner: Flag of Makara (摩羯旗)

The Makara is a legendary fierce sea-monster the size of a mountain, and always guards at doors and gates. This flag is believed to be able to bring the monster’s courage to warships defending the empire’s ports and straits. When the Liao fleet visited London, Sameul Pepys saw the flag and used to call it “the Leviathan Flag”. He didn’t get it quite right, but the comparison did point out the similar levels of powerfulness.

The Liao Official Ship Banner: Flag of Dharmachakra (Dharma Wheel) (寶輪旗)

Just like the case on land, Liao’s official ships on the sea, except for the warships, also hang the Dharmachakra flag. This flag has a more blue (bluer) tone, and is of the same scale as the naval flag.

The three Liao vessels “Hupo”, “Anji” and “Īśāna” accompanied by a Royal Navy’s third-rate warship on the Thames in the Small Theatre series. Note that on the tail of “Anji” the Dharmachakra flag was hanged to indicate the status of the imperial envoy, whereas the other frigates hanged the Makara flag(s).

The Liao Merchant Ship Banners: Flags of the Fortune-Gaining Mansion and of Pushya (Nourishing Mansion) (增財/熾盛旗)

Flag of Pushya

Flag of the Fortune-Gaining Mansion

As ships have been required to be subjected to inspections from the patrol battalions (巡護營) under the Bureaus of Foreign Shipping, the modern Liao has been keenly mindful of flags and banners of ships on the sea. Liao merchant ships originally hanged Dharmachakra flags, and after being prohibited to do so by the patrol battalions changed to pure blue flags.

As time went by, the merchants began to add some auspicious signs to their flags for luck, and these signs and patterns in the end gradually converged to the southern constellations familiar to all the ship captains.

Pushya, due to its lucky meanings, became the most popular choice. Some Han shipowners on the other hand voiced their dissent: Pushya had been known in the East Asian system as the “Ghost mansion” (鬼宿) and was thus unlucky. So instead they chose to fly the Well mansion (井宿) flag – the Well mansion was translated as the fortune-gaining mansion (增財宿) in some Buddhist sutras and seemed to carry a better meaning.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

There is more to this…

Stories about flags have no bound. For example, there is a special flag in Mahakhitan, called the tangerine/orange flag. Its story is more correlated to stories in the future, so let me leave this as a cliffhanger here, and save it for the later chapter about the Imperial Mahakhitan Navy.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Finally, желаю вам здоровья (zhelayu vam zdorov'ya – wish you good health), and until next time!