Chapter 26 Small Theatre: from Cathay to Ireland (Part Two)

026 – 小劇場:從契丹到愛爾蘭(下)

Picking up from last time,

the story was expanded a lot, but I can retract all these storylines…

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Story of Administrator of the Royal Navy Board

July 26th, 1661, Friday.

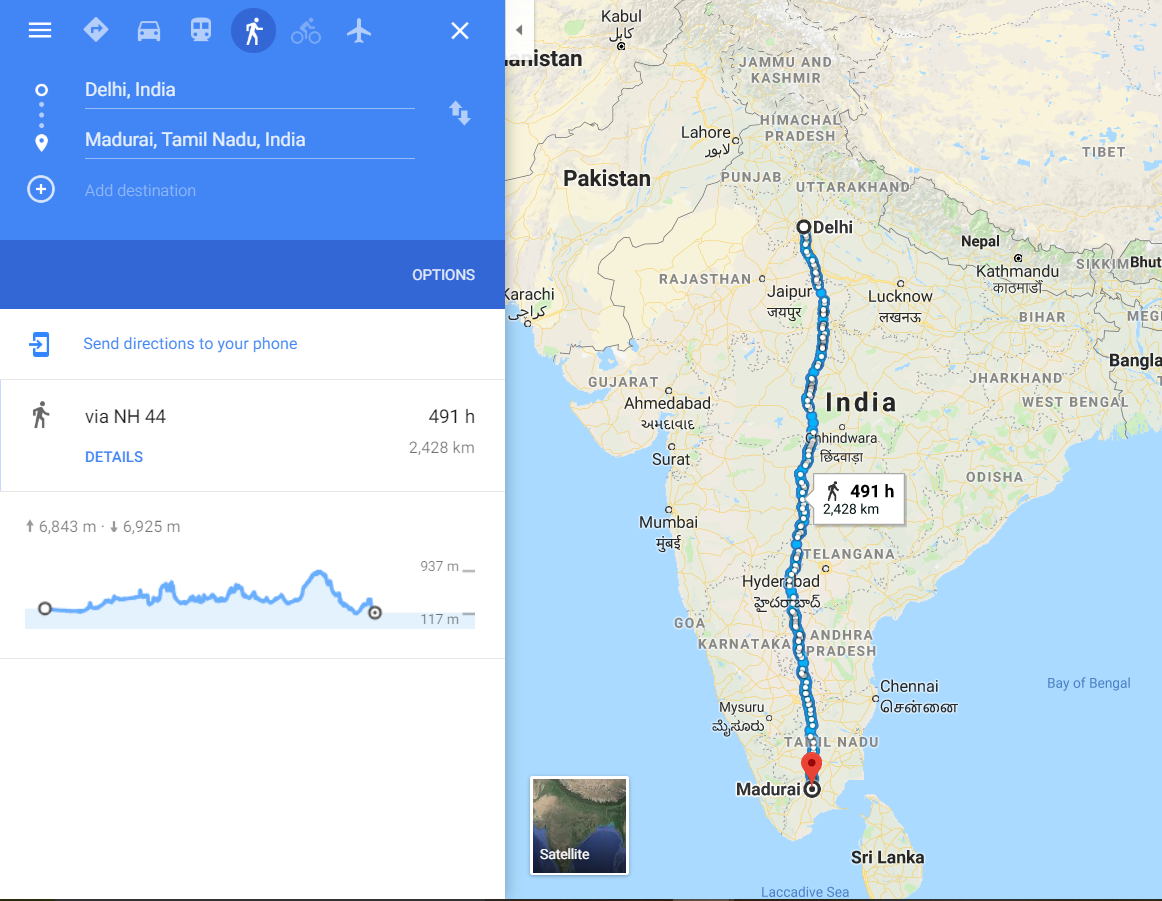

Got up early today. Went to Chatham with Sir Penn together by carriage. The largest Khitanistan ship was not terribly damaged, but the repair still took a great deal of effort. The facilities in Chatham are still being built, and the Khitan ships were built in very special ways – ocean barques but with triangular sails on all three masts are sufficient to surprise us, not to mention the panels and boards were completely seamed with ropes all ove the ships. The Khitan captain requested us to repaint the patterns on the sides. Seeing new, unfamiliar ships, old Penn jumped around like a maniac, not at all upholding the demeanour as an admiral. We had dinner with the Khitan officials. Although the Khitan interpreters only knew Greek and Sabir, that was all we needed to have pleasant conversations. Spent the night in Gillingham.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Story of the French Commissioner (Still Quite Long)

Monsieur Maisson and his colleagues from the French India Company were politely led aside almost as soon as their ship docked. The Khitan mission stayed in Chatham for a few days, negotiated with the English on the repair of the ships, and then Lord Xiao was escorted by the English to London by land. Then, the English led these French out of the critical base of the Royal Navy with maximal efficiency, and “politely placed” them in a disbanded monestry in Dartford.

Under such circumstances, Maisson still managed to record whatever news he heard about the Khitan mission in England:

Although the cussed English heresies kept us in this damp little town, we are only twelve leagues from London, so most news would only take a day to get here. I shall record what I hear one after another.

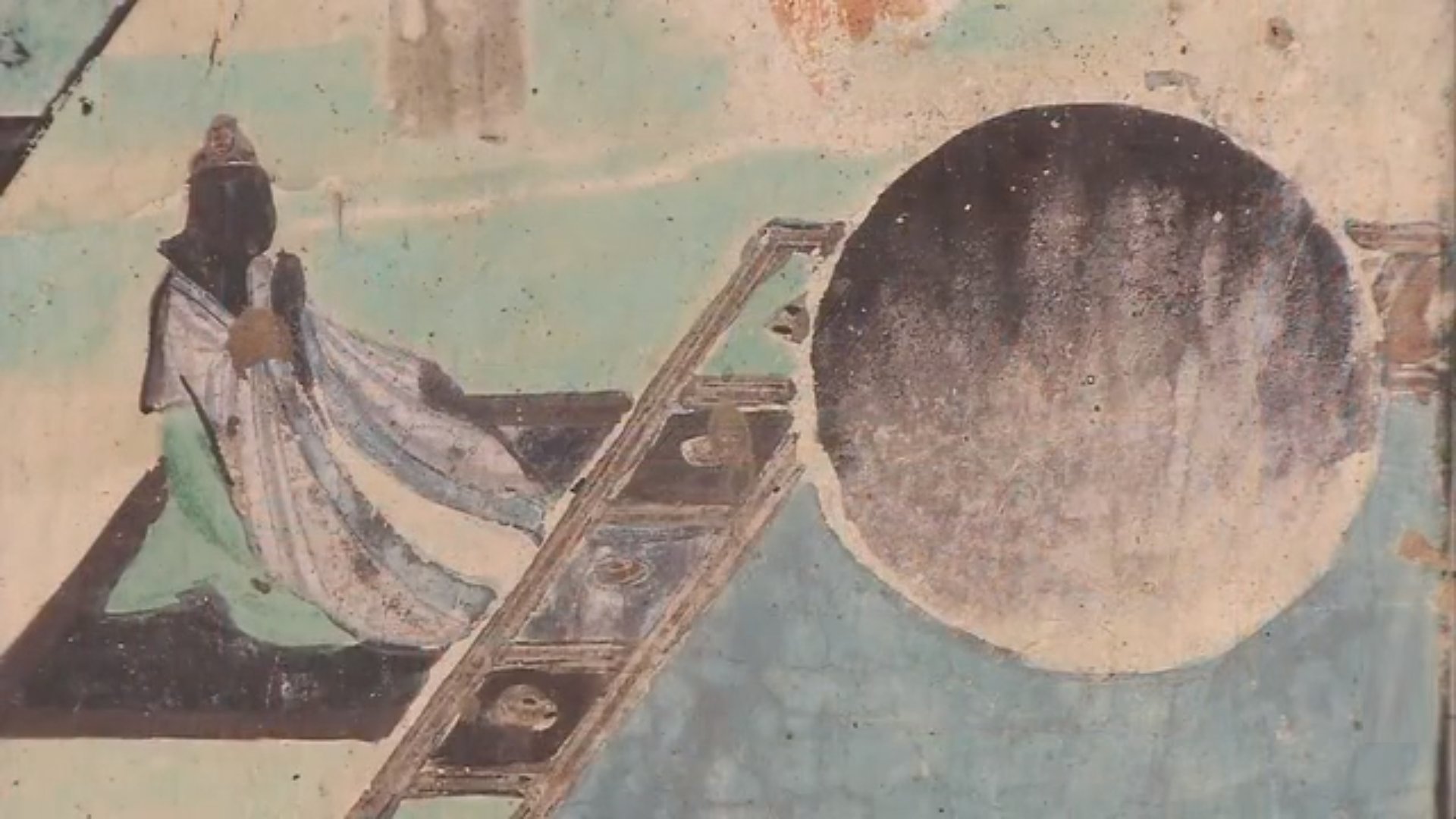

The Khitanistan envoy arrived in London on the 21st, and was accorded a grand reception. Apparently the English were gravely ashamed of what they did near the southern coast of Ceylon. Lord Xiao delivered a state diplomatic letter to the King of England. The letter is, according to the rules in the diplomatic system of Khitanistan, called “Shi” (敕) which means an edict, therefore although I never read its content, it is fair to imagine the wording must be very harsh.

Then the English seemed to have kept the Khitan envoys distracted in endless equestrian activities and hunting. Every public appearance of the Khitan envoys everywhere would drew countless local audiences. After two weeks, news came that England captured more than ten accomplices of Barlow in the English West Indies, and they were specially sent to London by the Royal Navy. These thugs, after being trialed by a special court in Westminster on St. Gregory’s Day, were hanged in front the Khitan mission. The Khitan vessel Anji was done with her repair, attended the execution with the other two warships, and fired a salute. The city of London was in an uproar because of the grand event.

The following three pages are all kinds of fancy complaints Maisson had about food of the English, which I will skip translating here~

Skipping over the part, let’s now talk about the even grander reception the Khitan envoys had in Paris after they left England.

His Majesty complained the extension project of the Versailles was showing little progress, so he could not move the Khitan mission with its majestic façade. So His Majesty invited the distinguished guests to Château de Fontainebleau. Despite Paris is indeed much more magnificent than London, we unlike the poor-tasted English refuse to let our respected envoys stay long in the city with suffocating air. The Khitans seemed to appreciate the arrangement very much.

His Majesty spent an astounding amount of 80,000 livres to prepare for this unprecedented gathering. Prince of Condé, Duke of Orléans and Duke of Berry, among others, attended the event. After four consecutive days of tea parties and dances, the premiere of Le Bourgeois gentilhomme by Monsieur Molière was on the night of the 3rd of March. With the excellent help of our interpreters from the East India Company, the comedie ballet managed to amuse the Khitan aristocrats including Lord Xiao so much that they staggered back and forth in laughter – indecency among the noveau riche is also a common scene in Khitan. The royal music director Monsieur Lully, to everyone’s surprise, even acted as a Greek bishop! The event was concluded with an unprecedented firework show.

One day before His Majesty’s birthday, led by Prince of Condé, four companies from the long prestigious Garde-du-Corps were reviewed by His Majesty and the Khitan envoys. Subsequently these most elite warriors in Europe demonstrated line infantry tactics and bayonet charges, while the royal artillery regiment presented volleys of gunfire. Lord Xiao showed deep interest in the invention of bayonets, and thoroughly enquired Prince of Condé about the tactics of line infantry as well as the formation training for bayonet engagement. The prince cleared Lord Xiao’s doubts and very pleasantly added a unscheduled demonstration where the Garde-du-Corps converted their formation from lines to squares to counter cavalry. Lord Xiao immediately proposed to invite French servicemen to India as advisors and His Majesty straightforwardly agreed.

Early 1663, after touring the north of France, the mission left the country from Brest. During the return, the Liao mission also visited Grenada, Andalusia, and was warmly welcomed by the king in Alhambra.

The voyage after that was smooth all the way. The Mahakhitan captains already gained experience of handling long journeys on the sea, and there were also ships from the French East India Company that accompanied the fleet, with more goods and commissioners.

More importantly, the Mahakhitan sailors found their new favourite during their stay in England of less than half a year – a beverage called beer. The captains trustingly allowed their men to consume it without limitations. As the beverage could also remain fresh for long periods of time, it quickly became the best drink for the Khitan life afloat. The East End of London style beer produced in Wuchuan Circuit even gained the name “Indian Pale Ale” in the English-speaking world ITTL

, or IPA in short.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Story of the Liao Emperor

1665, 18th Year of Mingshao of Liao.

When the mission returned to His Majesty’s palace, the Liezong Emperor himself had been tormented by his lung condition for several years and was almost completely drained of his energy. The imperial doctors sent by the emperor of the eastern realm

(Ming), monk doctors sent by the King of Ü-Tsang, pharmacists from Baghdad, and the French doctors with all of their Latin and Greek terms had been busy surrounding the emperor for two or three years, racking their brains all day, only showing barely any result.

His Majesty was in turn at ease himself. The Five Skandhas are all empty after all, the emperor told the imperial preceptor, the 25th-generation guardian of the First Central Gate of Nalanda, Master Jixian (寂賢

, lit. “Solitary Virtue”), and although he had led to many killings during the campaign against Pasai, committing deep, grave sins, he would unperturbedly accept any and all retribution and was even curious what would become of him in Saṃsāra.

The imperial preceptor naturally said things to comfort the emperor, as his duty required.

The biggest worry of the emperor was still what it meant for the future of the empire as western countries arrived via the ocean. Behind the hospitable reception and even excessive courtesy the English had shown towards the Xiao Gu (蕭固) mission was their powerful might and a kind of stubbornness that was difficult to comprehend. Their handling of the criminals this time showed this tendency precisely: instead of accepting the demand to send the inmates back to Mahakhitan for execution, the English publicly disposed of them on a carefully prepared rite in their own cruel way. Although this punishment of being coated in tar and then hanged in cages was indeed unheard of and quite deterring, so the Liao still managed to win back some face in front of the whole Europe, but what the empire needed the most was after all the old Liao-style punishment for pirates: salt-marinated then wind-dried hands and heads stuck up on the “Three Mountains Pillar”* (三山柱) on the seaside dam near the naval base/camp.

*A creation of Kara with probably no equivalence IOTL - a wide Trishula about one-man-tall, with the felon's head on the middle tip and his hands on the other two, left to be wind-dried for a year or so.

The emperor did not have any son that made it to adulthood, which meant Mahakhitan was to receive another empress after two hundred years.

Princess Yelü Mingxu was fifteen this year, and deeply fascinated by everything during the era of the Yizong Empress. The imperial house arranged her engagement to the crown prince of Hanshan, thus also reminding both the court and the commoners of the story between the Yizong Emperor and King Xuan of Shanyang two centuries ago.

Some nosy civilians came up the prophetic poem that crotchetily implied the the princess’ rule in the future would be like an echo of the late empress’ time.

Of course not, the emperor told his little princess. The world is not the same anymore, the ocean is no longer calm, things are changing behind the snowy mountains to the west, and the national treasury that seems to be full is also filled with holes. When you sit on the Diamond Throne, facing the longest day, you must be careful and stay alert.

The princess nodded, subconsciously clenching the curtain of the imperial bed.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Lastly we go back, to

Story of the English Pirate

This Henry Barlow dude, eh,

he fled with his own men after this one robbery of the Ten Thousand Year Convoy he committed. While on the run he also did not forget to make life for his culprit partners difficult. He first did not honour the promise he made to divide the loot with the other captains, ran all the way to the Caribbean, and then trapped his own brothers on the same ship, causing these hapless scums’ arrest by the hand of the Royal Navy. News was, their execution in London ran wild.

Then Barlow concealed himself and vanished from history.

But I’ve heard, and everyone seems to be saying this, that after a while Barlow started to slowly sell what he had when he felt the thing was over, but was tailed by a Greek fraud from New Naxos. The man cheated all of Barlow’s money with some financial operation-related gimmicky proposal, and simply disappeared. Word is, Barlow loitered around like a stray dog, got recognised by his former crew, and ended up dead in a drainage ditch in Port John Chrysostom of New Naxos (Fort-de-France Bay of Martinique IOTL).

I rather like this ending.

~ Fin ~ Thank you for reading~

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Record of the Western Regions~ the Returning Part Eight

It’s been a long time since I last wrote background introduction pieces. The small theatre series this time combines much fiction with historical reality, so I feel it is needed for me to write about the part from historical facts of OTL.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

The entire Ten Thousand Year Convoy robbery of the

Afflatus was inspired by the 1690s Indian Ocean big event IOTL – the

Ganj-i-Sawai (“Exceeding Treasure”) Incident. The large Mughal vessel en route from Hajj was attacked by the pirate Henry Every and his complices in the Mandab Strait of Red Sea, leading to inhumane pillage and ravage of the male and female pilgrims aboard, while the bountifulness of the loot also became an eternal legend. For those interested, please check further for the unfolding of the event and the subsequent rage of Aurangzeb. But of course for the Mughal Empire, even after 30 years

(than the event ITTL), its lack of focus on the sea made sure it could never dispatch large vessels to condemn the King of England.

The archetypal character of Henry Barlow is the main felon in the incident, Henry Every. As one of the most (in)famous figure in the history of piracy, he went after straggling ships, indulged his subordinates, wronged his partners, and ended up getting scammed to become a stray dog on the street of overseas colonies… these are all true stories. The ending of Barlow getting recognised and beaten to death was created by the negative and vengeful me

, to vent the anger for our Great Liao’s convoy.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

François Maisson is an imaginary figure of the Mahakhitan timeline, but his early-life experience is indeed identical to that of François Caron: being a Huguenot, working for the Dutch, becoming a high-rank executive in Japan, and then skipping back to his home country.

The part of France bears two differences from OTL, one being the French East India Company was actually only established in the 1660s, with Caron being the first director invited by the Minister of Finances of France Colbert. But in this timeline, the prosperity of maritime trade brought by [peace under Mahakhitan dominance] probably caused the company’s early establishment some ten-odd-years in advance.

The second deviation is that the premiere of Molière’s

Le Bourgeois gentilhomme was actually at Château de Chambord in 1670. But I simply love the play and the music from Lully too much, so I made Monsieur Molière finish it early regardless.

Lully did in fact play as a Turkish mufti, but a big and powerful East Rome instead of the Ottoman Turks emerged in the Mahakhitan timeline’s Near-East, so adjustments were made accordingly.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Lastly, although Samuel Pepys did not play a big part in the series, he was indeed a figure worth of a lot of coverage. His Excellency established a system of management regulations for modern British Royal Navy, but he is more famous for his diary between 1660 and 1669, in which he recorded important events in Britain back then, many interesting daily-life details of 17th Century, and infinite gossip material. I nearly became addicted to his diary while I was reading it a while back… The Small Theatre series contain two pieces of his diary, which I wrote while referring to the actual thing of roughly the same historical period.

Didn’t I also mention Sir W. Penn? He was an admiral of England back then, a fierce commander, and made frequent appearances in Pepys’ dairy as he was the latter’s colleague and neighbour. Pepys initially had a decent relation with Penn, but later found out about the admiral’s constant unreliability plus lack of integrity, so he gradually avoided him more. For more details, refer to their English Wikipedia entries.

But seriously, the young lad Pepys himself had questionable integrity as well… on the day in

OTL after seeing the Liao vessels in Chatham in this series, Sunday July 28th, 1661, Pepys first met Penn’s daughter Margret at church (

Faust anyone?). His comment was “thought she was a beauty but turned out to be average”, but later Pepys still had inexplicable entanglement with Penn’s daughter and wife… one day I specifically went over Pepys’ diary to look into the story, and it was so fun.

Oh and also, the King of England owed Admiral Penn money and couldn’t pay him back, so His Majesty instead paid with land in the New World. Penn’s son William Penn got the piece of land, which became known as Pennsylvania, woods of the Penns literally.

(Finished on the train in Pennsylvania… oops.)

Boundary marker of Pennsylvania, showing the Penns’ coat of arms; saw this a few days ago at a museum.

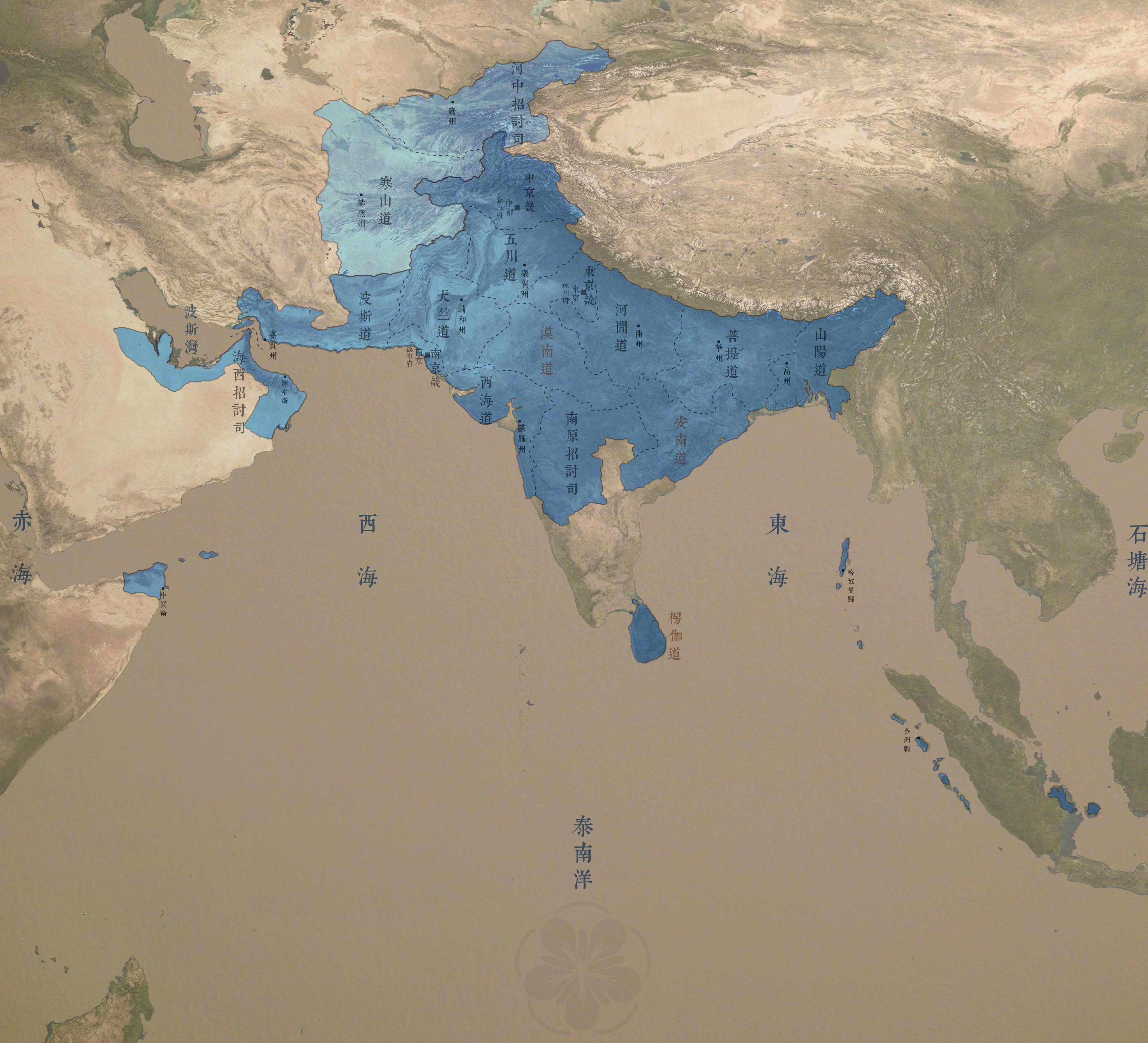

....She’s conquered parts of Persia,parts of Arabia,Central Asia,Ceylon and even parts of the Spice Islands,but she leaves out Southern India.She even wrote in one of the updates that Ceylon gets raided by the Southern India states frequently.