You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Extra Girl: For the first heaven and the first earth were passed away.

- Thread starter Dr. Waterhouse

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 109 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Supplemental Note on Contemporary Crime, New Amsterdam Supplemental Note, The Construction of the Elbe Underpass, 20th Century Supplemental on the History and Goverment of New Amsterdam The Life of Elector Alexander of Saxony, 1566-1567 The Life of Elector Alexander of Saxony, 1567-1571 The Life of Julius of Braunschweig, 1550-1571 Supplemental Note on the Contemporary German Imperial Monarchy The Life of the Elector Alexander of Saxony, 1569-1573

The Life of Elector Friedrich IV, Saxony, 1523-34

.jpg)

Sibylle of Cleves by Lucas Cranach (1526, the actual portrait rendered on her betrothal to the Duke Johann Friedrich)

from Enthusiast: A Magazine of Royal History

Friedrich and the Four Princesses: How the Holy Prince got his consort.

Dorothea, Princess of Denmark

During the rule in Saxony of Elector Friedrich III the Wise, while Elizabeth was still a duchess and her son Friedrich still just the son of the elector’s younger brother, she agitated for an English match for her firstborn son. Failing that, she insisted that any bride for the young Friedrich be of royal blood. While the Ernestine Wettins had less interest than Elizabeth in plotting to win the English throne, they took to heart her admonitions that any match for the heir in the generation after her not the daughter of a king would be a step down.

Christina, the elder sister of Friedrich III and Johann had become queen of Denmark. A renewal of the Danish alliance by marriage was to the Wettin princes more practical than competing with the Habsburgs and Valois for the hand of the Princess of Wales. However, these negotiations were upended in 1523, when rebellious nobles evicted the king of Denmark and installed in his place his uncle. The previous, deposed king had been the son of Christina of Saxony, Queen of Denmark, whereas the new one was her brother-in-law.

That said, the new Danish king, Frederik I, was willing to consider a match with Saxony between Duke Friedrich and his daughter Dorothea, to cement the acceptance of his rule, and resistance among the Wettins to such a plan was slight. Christina had already died some years prior, and they felt little was to be gained in snubbing Denmark’s new king.

Where these plans ran aground was that the new Danish king ultimately preferred a match with the newly created Duchy of Prussia, which would give his kingdom a competitive advantage in the never-ending struggle for power in the Baltic. Thus, the Wettins’ overtures were set aside, and Dorothea wed Duke Albrecht of Prussia in 1526.

Sybille of Cleves

Few possible electoral consorts were more attractive than Sybille of Cleves. Her father Johann was the heir to the dukedom of Cleves and the county of Mark. Her mother Maria was heir to the dukedoms of Juelich and Berg and the county of Ravensberg. If her brother Wilhelm died, Sybille as the eldest daughter was herself heir to the combined patrimony of her mother and father. Thus in the 1520’s the Wettins eagerly pursued the match, thinking that the pairing of Sybille with Friedrich would bring under the Ernestine Wettins a large collection of prosperous territories clustered around the Rhine.

The complications this idea ran into had less to do with any misgivings of the House of Marck for the Wettins than with arrangements surrounding the Wettin succession. Elizabeth had bore Johann two surviving sons, Friedrich and Johann the Younger. Almost as much as she disliked the idea of a non-royal match for her eldest son, she disdained the Saxon custom of divided inheritance. So she was able to prevail upon Friedrich to offer the match with Sybille of Cleves to Johann the younger, which would mean that if she inherited by jure uxoris he would be Duke of Juelich, Cleves and Berg, and Count of Mark and Ravensberg. But in return, Johann would have to agree to the rule of primogeniture within Saxony both with respect to himself and his heirs.

In addition to the matter of inheritance, Sybille was beautiful and high-spirited. Johann accepted, the Duke of Cleves was pleased to not have his realms subordinated within a larger Wettin super-state stretching across northern Germany, and Elizabeth and Friedrich the Younger were able to return to their more grandiose schemes for a royal match. Johann the Younger and Sybille of Cleves married in 1527.

Because Wilhelm inherited his parents’ lands instead of his older sister Sybille, the dynastic plan of the Wettins on the Rhine came to nothing, for the moment. However, in eighty years a similar question of succession would trigger the conflict that would be the prologue to the First General War. In the meantime, Johann the Younger and Sybille’s marriage would be happy, though their involvement in the crises of the sixteenth century was anything but uneventful.

Mary I of England

It might seem strange for contemporary readers to imagine, but for a long time the future Queen Mary I was mooted as a marriage prospect for the future Elector Frederick IV of Saxony. Though Mary spent most of her early years betrothed to either Emperor Charles V or King Francis I, the electoral court hoped that Duke Friedrich’s Tudor blood would give him a chance at marrying Henry VIII’s heir. During this time, because of the absence of a previous tradition of female rulers in England, it was presumed actual rule would pass to the queen’s husband. The Saxons believed this would make Friedrich a more palatable choice to the English than their traditional enemies the French or the alien Spanish.

Following the annulment of Henry VIII’s marriage to Katherine of Aragon, Mary was de-legitimized. This was sufficient to end the possibility of a match with Charles V, but it only enticed the Saxon court further. In the schemes of the Electress Elizabeth, the bastardization of the “Lady Mary” would amount to a small matter in the event King Henry died without lawful male issue. Thus the Saxons sought her hand constantly, and had in their unlikely corner the Imperial Ambassador, Eustace Chapuys. The Empire lent its support to the project likely as little more than a ruse to get Mary out of the country and the control of her father. What would have happened had she arrived on the continent, who knows?

The role of religion in the matter was magnified over time. Distaste for the Wettins’ Lutheranism was cited not just in Mary’s objections to the project but Henry’s too. The Electress Elizabeth for her part tried to leverage some promise of a return to the Roman Catholic fold in order to win Mary’s hand for her son, but in these matters she clearly ventured beyond her authority and contradicted the wishes of first her husband the Elector Johann the Steadfast, and after that her son Friedrich IV.

Nonetheless, the effort to win Mary’s hand, and with it the English Succession for the House of Wettin, was so obsessive it was only until after the Elector and his mother paid their unsuccessful 1533 visit to England, in which Elizabeth was only able to win the consolation match of the marriage of her daughter Katarina to the Brandon heir, Henry Earl of Lincoln, that serious negotiations began for another match.

(The Other) Dorothea of Denmark

Unlike the other Dorothea, she was the daughter of the usurped king Christian II and granddaughter of Christina of Saxony. Dorothea’s mother was Isabella, sister of the Emperor Charles V. Following her father’s overthrow in 1523, the former Danish royal family fled to Friedrich the Wise’s court in Saxony. This was during the period of the Duchess Elizabeth’s confinement away from the court, so she had no interaction with Christian II, Isabella or their children. However, Queen Isabella, only 22, made a strong impression on the young Duke Friedrich. For her part, Dorothea was only a child of two. Failing to receive the assistance in retaking the throne they desired from the Elector Friedrich the Wise, they left for the Burgundian court in the Netherlands maintained by Margaret of Austria and Mary of Hungary.

In these travels both Christian and Isabella expressed interest in the ideas of reformed religion. Christian in fact corresponded with Luther. Though young, Isabella died not long after she arrived in the Netherlands. Following her death, Dorothea and her younger sister were taken from their father because he was seen as a heretic. In 1532, Dorothea’s brother Hans died, which meant that she would be the heir to her father’s claim to the Danish throne. Immediately thereafter Dorothea began receiving interest as a marriage prospect for various young rulers and heirs, including James V of Scotland and Henry, Duke of Richmond.

Early overtures by Friedrich the Wise and Johann the Steadfast for a marriage between the young Friedrich and Dorothea had been rejected pending the end of their assistance to Luther and Saxony’s return to Roman Catholicism. Following the death of the Elector Johann in 1532, Friedrich the Younger renewed these efforts and was told the price of Dorothea’s hand would be the relinquishing of the Reform movement and the restoration of traditional religious practice in Saxony, regardless of any arrangements that could be made with respect to recapturing for Dorothea the Danish crown.

By now all the schemes for a marital alliance with the reigning Danish royal family or with the Tudors had failed. Friedrich IV now determined to pursue the match with Dorothea, daughter of the exiled Danish king, even in the face of this intransigence, but with a motive that had very little to do with a dowry, territory or any potential gambit to recover the Danish throne. Friedrich IV believed Charles V would be loath to make war on his own niece and her heirs, and so believed marrying Dorothea and making her the mother of the future electors of Saxony would provide the only durable means of preventing the emperor from going to war to reclaim Saxony for Roman Catholicism.

By 1534 the young elector was 23, unmarried, and ruling without an heir of his body. A pose of desperation on his part was plausible, to say the least. Thus he opened formal negotiations over Dorothea with Mary of Hungary, who was acting on behalf of the emperor, with no preconditions. In the secret final agreement, reached June 26, he assented through his ambassadors to return to the Church of Rome, cease the suppression of religious orders and return all church property, though not to surrender the person of Luther or engage in any violence against believers in the Lutheran faith. Perhaps best of all for the Habsburgs, the young Friedrich would recognize the election of Ferdinand, King of Bohemia and Hungary, as King of the Romans, a substantial reversal of one of his father’s policies. He would immediately raise an army to restore King Frederik to the Danish throne on the understanding that the inheritance would pass to his wife, on whose behalf he would rule, and through her to their heirs.

It was the understanding that because the Elector Frederick’s younger brother, a devout Lutheran, would likely revolt on the occasion of the re-imposition of the Catholic faith, the terms would have to remain secret for long enough to allow the Elector to get physical custody of him and secure him. Finally, though the treaty provided for a rich dowry from the Habsburgs, it was only payable on the publication of all the terms of the treaty.

After the treaty was circulated to the Emperor and the King of the Romans, additional terms were demanded. Thus when Friedrich arrived in Brussels to gather his bride, he was confronted with the insistence that all the terms be made known at once, or else the marriage could not go forward. Friedrich IV refused, but added in his counter-offer a spectacular inducement to the Habsburgs: he would surrender Luther. As to publication of the terms, Friedrich insisted that to proceed with an immediate publication would be equivalent to surrendering his lands to his brother, as there would be no way he could rule Saxony as a Catholic without first resolving the problem of Johann the Younger.

Moreover, Friedrich protested, this was the fulfillment of his mother’s fondest wish for him. The electress dowager was with him in Brussels, and he ably deployed Elizabeth in meetings with Mary of Hungary to verify his intent to follow through the treaty. And without hesitation, he took Catholic communion. And so Mary of Hungary relented. On September 23, Friedrich and Dorothea were married in a Roman Catholic ceremony at the court in Brussels, during which Friedrich showed unfamiliarity, but not reluctance with the Latin and other traditional elements of the service.

Together, he, his mother, and his new bride then promptly returned to Wittenberg, where Friedrich announced he was not bound by the treaty. Dorothea had no trouble demonstrating the love for the reformed faith instilled in her by her parents, and on her arrival kissed a copy of the German New Testament in the market at Wittenberg. Then Friedrich and Dorothea were married in a second ceremony, which was officiated by Martin Luther himself.

On its surface, the agreement negotiated by Mary of Hungary had been a windfall for the House of Habsburg: it would bring back into the fold the most prestigious German defender of Lutheranism, it secured his recognition of Ferdinand as King of the Romans, it committed the young Elector to try to restore the emperor’s niece to the throne of Denmark, and in doing so, it would create an enormous military distraction in northern Europe which would work to increase the net strength of the House of Habsburg.

But even as that mirage dissipated, and Martin Luther proclaimed Friedrich and Dorothea man and wife, the full measure of the betrayal had not yet been registered. In lieu of the Habsburgs’ promised dowry, Friedrich received a huge indemnity from King Frederik I of Denmark, whereby he disclaimed the succession to Denmark on part of himself and his and Dorothea’s descendants, similar to a famous instrument whereby he disclaimed the English succession. King Christian would not be restored to his throne by Saxon force of arms. The Saxons would not be militarily occupied waging war against Denmark. The Saxon electors were now more identified with Lutheranism than ever. And their heirs would have Habsburg blood, creating uncertainty as to whether, even if all were lost, they could be easily committed to an auto da fe.

Last edited:

Good updates; can't wait to see more and subscribed...

Hope this gets nominated for 2019's Turtledoves, @Dr. Waterhouse...

Hope this gets nominated for 2019's Turtledoves, @Dr. Waterhouse...

Good updates; can't wait to see more and subscribed...

Hope this gets nominated for 2019's Turtledoves, @Dr. Waterhouse...

Thank you!

The Life of Elector Friedrich IV: Supplemental Note on the English Succession

ASK PROFESSOR BENN

(English History, November, 1977)

Why didn't the Wettins become Kings of England?

Q: In my history class we were discussing the War of the English Succession. I think I understand why the Brandons were able to defeat the Stuarts, and why the help of the Ernestine Wettins was so important in their winning the throne. But what I don't understand is why the Saxon electors were helping the dukes of Suffolk in the first place. Margaret Tudor was born in 1489. Elizabeth Tudor was born in 1492. Mary Tudor, from we all know the Brandon claim comes, was born in 1497. Didn't the Saxons have the better claim to the throne in the first place?

A: No doubt the Electress Elizabeth, were she alive today, would think the same as you do! She ardently plotted ways for her son to succeed, either on his own, or by, jure uxoris, marriage to Mary I. This had much to do with the famous visit to England of the Saxon elector and his mother in 1533. Now, much attention in the historiography of this momentous visit is given to the pageantry, the opulence, and the drama. The Electress Elizabeth's slights against a pregnant Anne Boleyn and her efforts to meet Katherine of Aragon pushed diplomatic matters to their breaking point on their own. Add to that the young Elector challenging a morbidly obese and unwell Henry VIII to joust in the German style, which is to say, standing in the stirrups, and without a barrier between the two oncoming horses, and we are very lucky all the principles ended the visit intact, and without a very immediate succession crisis at that.

But beneath all that, King Henry found his nephew far more pragmatic than his sister. It was Elizabeth who had planned the visit around the fool's errand of a match between young Friedrich and the Lady Mary. As ever, Friedrich had his own agenda which he had not apprised her of. He wanted a military alliance, he wanted a stipend, and in return he was willing, quite grankly, to sell his place in the English succession. All this found a receptive ear in an English king deeply anxious about, first the possibility of an invasion by the continental Catholic powers and second, an effort by foreign claimants (read: the Stuarts) to usurp the throne from the son he was certain Anne was either carrying at the time or would shortly bear him. Thus in the Treaty of Windsor, which obligated uncle and nephew to come to each other's aid if attacked and which gave Friedrich his much-desired stipend, Friedrich disclaimed forever, for himself and his heirs, the English throne, and to respect absolutely Henry's wishes in the matter of succession.

In fact, it is this precise Treaty of Windsor that the Saxon elector Alexander would cite in 1603 when he intervened in the disputed English succession. Alexander cited Henry VIII's will, which specified the English throne would go first to Henry's children, and then after that the descendants of his youngest sister Mary, in joining the Testamentarian side of the war against the Stuarts. Would that this was the last time we would face the thorny question of whether the English throne could be handed down in a will, like a grandmother's wedding ring!

Of course, there were also some secret terms to the treaty between Henry VIII and Friedrich IV having to do with the Brandons, and specifically the person of the same young Earl of Lincoln whom the treaty betrothed to Friedrich's sister, but we need not deal with them here as they are unnecessary to your question.

Below: a replica, as The State Imperial Crown of England, in use for all coronations of the kings and queens of England from at least 1521 to the present day.

(English History, November, 1977)

Why didn't the Wettins become Kings of England?

Q: In my history class we were discussing the War of the English Succession. I think I understand why the Brandons were able to defeat the Stuarts, and why the help of the Ernestine Wettins was so important in their winning the throne. But what I don't understand is why the Saxon electors were helping the dukes of Suffolk in the first place. Margaret Tudor was born in 1489. Elizabeth Tudor was born in 1492. Mary Tudor, from we all know the Brandon claim comes, was born in 1497. Didn't the Saxons have the better claim to the throne in the first place?

A: No doubt the Electress Elizabeth, were she alive today, would think the same as you do! She ardently plotted ways for her son to succeed, either on his own, or by, jure uxoris, marriage to Mary I. This had much to do with the famous visit to England of the Saxon elector and his mother in 1533. Now, much attention in the historiography of this momentous visit is given to the pageantry, the opulence, and the drama. The Electress Elizabeth's slights against a pregnant Anne Boleyn and her efforts to meet Katherine of Aragon pushed diplomatic matters to their breaking point on their own. Add to that the young Elector challenging a morbidly obese and unwell Henry VIII to joust in the German style, which is to say, standing in the stirrups, and without a barrier between the two oncoming horses, and we are very lucky all the principles ended the visit intact, and without a very immediate succession crisis at that.

But beneath all that, King Henry found his nephew far more pragmatic than his sister. It was Elizabeth who had planned the visit around the fool's errand of a match between young Friedrich and the Lady Mary. As ever, Friedrich had his own agenda which he had not apprised her of. He wanted a military alliance, he wanted a stipend, and in return he was willing, quite grankly, to sell his place in the English succession. All this found a receptive ear in an English king deeply anxious about, first the possibility of an invasion by the continental Catholic powers and second, an effort by foreign claimants (read: the Stuarts) to usurp the throne from the son he was certain Anne was either carrying at the time or would shortly bear him. Thus in the Treaty of Windsor, which obligated uncle and nephew to come to each other's aid if attacked and which gave Friedrich his much-desired stipend, Friedrich disclaimed forever, for himself and his heirs, the English throne, and to respect absolutely Henry's wishes in the matter of succession.

In fact, it is this precise Treaty of Windsor that the Saxon elector Alexander would cite in 1603 when he intervened in the disputed English succession. Alexander cited Henry VIII's will, which specified the English throne would go first to Henry's children, and then after that the descendants of his youngest sister Mary, in joining the Testamentarian side of the war against the Stuarts. Would that this was the last time we would face the thorny question of whether the English throne could be handed down in a will, like a grandmother's wedding ring!

Of course, there were also some secret terms to the treaty between Henry VIII and Friedrich IV having to do with the Brandons, and specifically the person of the same young Earl of Lincoln whom the treaty betrothed to Friedrich's sister, but we need not deal with them here as they are unnecessary to your question.

Below: a replica, as The State Imperial Crown of England, in use for all coronations of the kings and queens of England from at least 1521 to the present day.

Last edited:

I'm not familiar with the first iteration of this TL and my knowledge of Tudor history is admittedly patchy at best, but this has been incredibly well-written so far. You're doing a good job of adding background info, though, so even a novice like me can follow along. I wish I knew more about the period so I could comment in more detail, but you can be sure that I'll be reading with interest!

Prefatory Note IV: The Rise of the Brandons

Prefatory Note IV: The Origins of the Brandons

William and Thomas Brandon were knights from Suffolk part of an affinity loyal to Edward IV. In particular, William had an unsavory reputation, and was once accused of the attempted rape of an old woman. The brothers were involved in Buckingham's revolt against Richard III, and fled to France following its failure, William with his pregnant wife. There they joined the court-in-exile of Henry Tudor. The next year when Henry Tudor landed at Milfordhaven, the Brandons were part of his army. In the Battle of Bosworth, William Brandon was Henry Tudor's standard-bearer. In the heat of the battle, when Richard III mounted a desperate attempt to reach and kill Henry Tudor, he personally struck William Brandon down.

Charles Brandon was the son William's wife, Elizabeth de Bruyn, carried when they crossed the channel. Born in 1484, after the accession of Henry VII he was raised at court. He first appears in the lives of the Tudors as a companion to Prince Arthur. His uncle, Thomas Brandon, assumed several important positions at Henry VII's court, including master of the horse. The Brandons held lands, a house in Southwark, and several streams of revenue from lucrative positions like the King's Bench.

While at court, Charles romanced Anne Browne, the daughter of a prominent courtier. While in pre-contract, he got her pregnant. He then broke off their betrothal to marry her aunt, Margaret Mortimer. During that brief marriage, he engaged in a number of self-interested land transactions from which he made a significant amount of money. Brandon then annulled the marriage with Mortimer, and after a difficult period of reconciliation that may have included a forcible abduction, he married Anne. After bearing Charles a second daughter, Anne died.

During this same period Charles' skill on the tiltyard and his close friendship with the young Henry VIII distinguished him at court. Thus after Anne's death Charles was given the wardship of the young noblewoman Elizabeth Grey, Viscountess Lisle. Charles was then able to betroth himself to the seven year old Grey, and use the title Viscount. Following his successful participation in the campaigns of 1514 he then received the dukedom of Suffolk in his own right.

Brandon during this period also attempted to woo Margaret of Austria, who had previously been betrothed to Charles VIII of France, then married to Prince Juan the heir of Ferdinand and Isabella, and after him to Duke Philibert of Savoy. Margaret was at this time tutress and regent to the young prince who would become Charles V, who was in turn betrothed to Princess Mary Tudor. Had Charles Brandon's scheme worked out, he would have been married to Margaret at the same court Mary would be as the consort of Charles V.

When the alliance of the Tudors and Habsburgs was broken in 1514, Mary was married not to Charles of Castile but to Louis XII, of France. She was 17, he was a gouty 52. Charles accompanied Mary to France, famously fought in the tournaments celebrating the marriage, and for the next several months served as an envoy between Henry and Louis. During these times, he developed a rapport with Louis too, and chatted amiably with him in his chambers.

And in what I am sure is an innocent coincidence, Mary's lady of the bedchamber as Queen of France, Joan Guildford, was engaged in a complex real estate leaseback transaction with Brandon involving the house in Southwark, herself having been left in deep debt following the death of her husband. And not long after the wedding, Louis sent Guildford back to England with many of the rest of the Englishwomen Mary wanted to have with her at court. Allowed to stay was one Anne Boleyn.

Louis died on New Year's Day, 1515, the sixteenth century gossip being he had exhausted himself sexually with his young bride. After his death, Mary entered the mandatory period of sequestration prescribed for the widows of all French kings in order to make sure they did not carry a child significant to the succession. During this time she was visited by the new putative king, Francois I, in what may have been an effort to manufacture suspicion of bastardy with respect to any heir of Louis's she might produce. During this time, Brandon also visited her.

Francois wanted to assert his right to control Mary's remarriage as a woman of the House of Valois, just as Henry wanted Mary for another diplomatic match. Henry had apparently promised Mary she could have a love match as her second marriage before her departure for France, but now thought better of it. Mary in response became desperate, histrionic correspondence went back and forth between Charles and Mary and key figures at the English court, and as Brandon explained because he felt Mary might do herself harm if he refused her, he agreed to marry her.

Francois relented, and with everyone convinced Mary was not bearing a son of Louis XII, he permitted them to leave. Charles and Mary then absconded with a fortune in jewels that they claimed Louis XII had given her, but which apparently were part of the collection of the French crown. Also, Mary was permitted to keep some lands in France previously negotiated for her, basically making the Suffolks economically dependent on revenues that the French king could shut off in a time of war. In England, they faced Henry's fury, but he forgave the couple following their agreement to a huge indemnity whereby Brandon agreed to pay Henry a huge amount of money spread out over a great many years.

Mary then bore Brandon several children, whom we will save for later. During the rise of Anne Boleyn Charles positioned himself as an ally of the Boleyns, while Mary remained loyal to Katherine of Aragon, whom by now she had known, and thought of as a sister-in-law, for almost thirty years. Because Mary did not want to recognize Anne as queen in the etiquette of the court, she stayed away at the Suffolks' estates. Brandon, for whom proximity to the king was indispensable, stayed. Mary grew sick with cancer while Brandon was assisting Henry VIII with Anne Boleyn's coronation, and died that summer.

In 1528, while Brandon and Mary was still married, Henry VIII had given Brandon the wardship of one Katherine Willoughby. Brandon planned to marry Willoughby to his own heir. But once Mary died, he decided to marry Willoughby himself, waiting all of three months after Mary died. He was 49, she was 14. With her he had more children.

Also, at Mary Tudor's funeral, apparently the first two Brandon daughters were unhappy that they held a lower place of respect than Brandon's children by the queen, so there was something of an undignified shoving match.

Finally, around the time Brandon himself died in 1545 Henry was growing dissatisfied with his queen at the time, Katherine Parr. He considered Willoughby as a potential queen #7. After Henry VIII died, Parr herself remarried, to Thomas Seymour. Parr then died herself in childbed with Seymour's daughter, who was given to Katherine Willoughby to raise, since they were actually good friends.

Katherine Willoughby was known not just for her beauty, but for her learning, piety and fierce Protestantism.

Now in our timeline, not only Brandon's sons by Mary Tudor, but his sons by Katherine Willoughby who could continue the Suffolk title, die out. This is probably a good place to leave things, since it is these deaths where the timeline starts to play with the fortunes of the Brandon family.

What I would leave you all with is this: in the world of the timeline the Brandons, the timeless and eternal royal family of England, are known for their piety, fidelity and above all, their moral integrity.

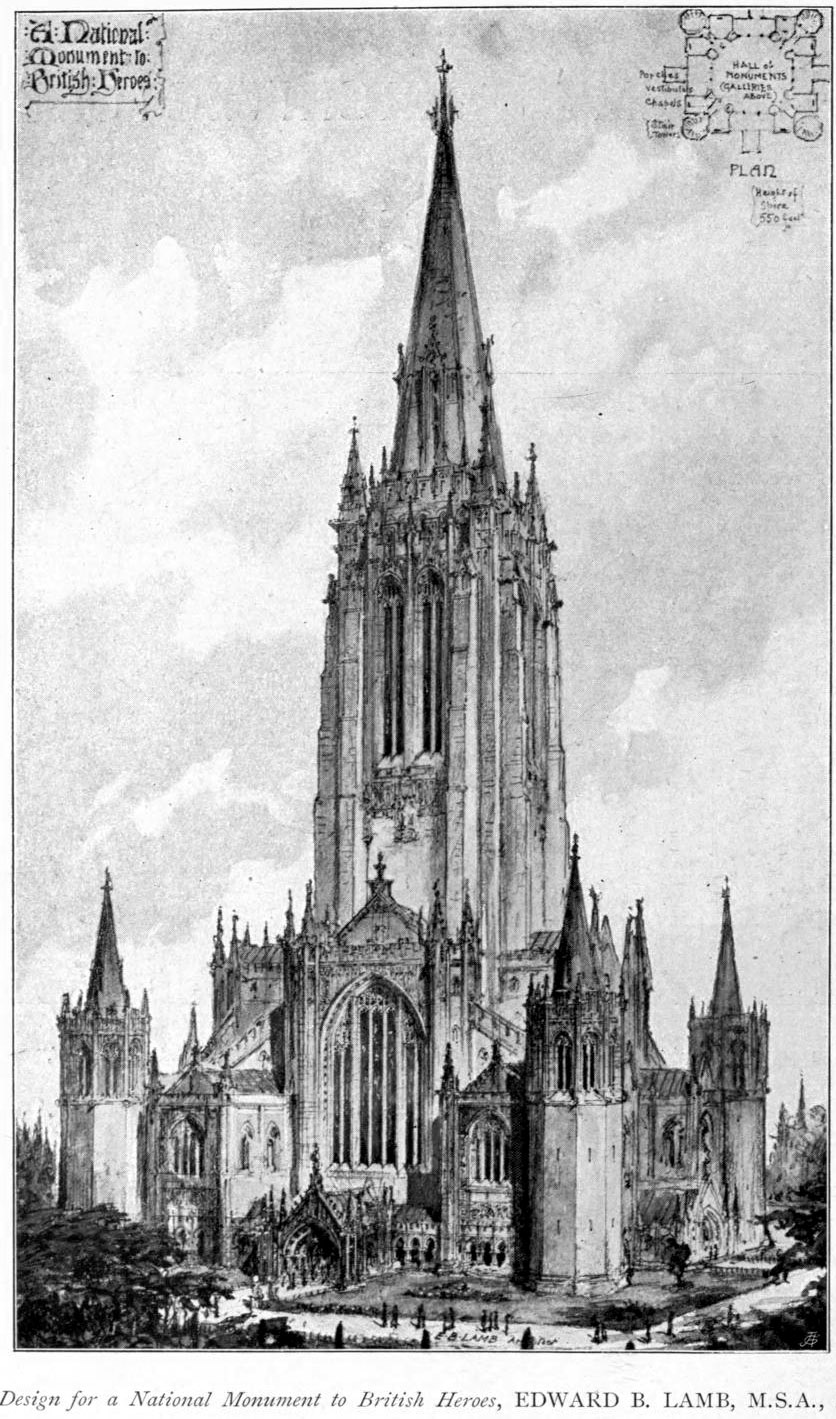

Below, a projected Monument to British Heroes, 19th century, as The William Brandon Monument at Bosworth

William and Thomas Brandon were knights from Suffolk part of an affinity loyal to Edward IV. In particular, William had an unsavory reputation, and was once accused of the attempted rape of an old woman. The brothers were involved in Buckingham's revolt against Richard III, and fled to France following its failure, William with his pregnant wife. There they joined the court-in-exile of Henry Tudor. The next year when Henry Tudor landed at Milfordhaven, the Brandons were part of his army. In the Battle of Bosworth, William Brandon was Henry Tudor's standard-bearer. In the heat of the battle, when Richard III mounted a desperate attempt to reach and kill Henry Tudor, he personally struck William Brandon down.

Charles Brandon was the son William's wife, Elizabeth de Bruyn, carried when they crossed the channel. Born in 1484, after the accession of Henry VII he was raised at court. He first appears in the lives of the Tudors as a companion to Prince Arthur. His uncle, Thomas Brandon, assumed several important positions at Henry VII's court, including master of the horse. The Brandons held lands, a house in Southwark, and several streams of revenue from lucrative positions like the King's Bench.

While at court, Charles romanced Anne Browne, the daughter of a prominent courtier. While in pre-contract, he got her pregnant. He then broke off their betrothal to marry her aunt, Margaret Mortimer. During that brief marriage, he engaged in a number of self-interested land transactions from which he made a significant amount of money. Brandon then annulled the marriage with Mortimer, and after a difficult period of reconciliation that may have included a forcible abduction, he married Anne. After bearing Charles a second daughter, Anne died.

During this same period Charles' skill on the tiltyard and his close friendship with the young Henry VIII distinguished him at court. Thus after Anne's death Charles was given the wardship of the young noblewoman Elizabeth Grey, Viscountess Lisle. Charles was then able to betroth himself to the seven year old Grey, and use the title Viscount. Following his successful participation in the campaigns of 1514 he then received the dukedom of Suffolk in his own right.

Brandon during this period also attempted to woo Margaret of Austria, who had previously been betrothed to Charles VIII of France, then married to Prince Juan the heir of Ferdinand and Isabella, and after him to Duke Philibert of Savoy. Margaret was at this time tutress and regent to the young prince who would become Charles V, who was in turn betrothed to Princess Mary Tudor. Had Charles Brandon's scheme worked out, he would have been married to Margaret at the same court Mary would be as the consort of Charles V.

When the alliance of the Tudors and Habsburgs was broken in 1514, Mary was married not to Charles of Castile but to Louis XII, of France. She was 17, he was a gouty 52. Charles accompanied Mary to France, famously fought in the tournaments celebrating the marriage, and for the next several months served as an envoy between Henry and Louis. During these times, he developed a rapport with Louis too, and chatted amiably with him in his chambers.

And in what I am sure is an innocent coincidence, Mary's lady of the bedchamber as Queen of France, Joan Guildford, was engaged in a complex real estate leaseback transaction with Brandon involving the house in Southwark, herself having been left in deep debt following the death of her husband. And not long after the wedding, Louis sent Guildford back to England with many of the rest of the Englishwomen Mary wanted to have with her at court. Allowed to stay was one Anne Boleyn.

Louis died on New Year's Day, 1515, the sixteenth century gossip being he had exhausted himself sexually with his young bride. After his death, Mary entered the mandatory period of sequestration prescribed for the widows of all French kings in order to make sure they did not carry a child significant to the succession. During this time she was visited by the new putative king, Francois I, in what may have been an effort to manufacture suspicion of bastardy with respect to any heir of Louis's she might produce. During this time, Brandon also visited her.

Francois wanted to assert his right to control Mary's remarriage as a woman of the House of Valois, just as Henry wanted Mary for another diplomatic match. Henry had apparently promised Mary she could have a love match as her second marriage before her departure for France, but now thought better of it. Mary in response became desperate, histrionic correspondence went back and forth between Charles and Mary and key figures at the English court, and as Brandon explained because he felt Mary might do herself harm if he refused her, he agreed to marry her.

Francois relented, and with everyone convinced Mary was not bearing a son of Louis XII, he permitted them to leave. Charles and Mary then absconded with a fortune in jewels that they claimed Louis XII had given her, but which apparently were part of the collection of the French crown. Also, Mary was permitted to keep some lands in France previously negotiated for her, basically making the Suffolks economically dependent on revenues that the French king could shut off in a time of war. In England, they faced Henry's fury, but he forgave the couple following their agreement to a huge indemnity whereby Brandon agreed to pay Henry a huge amount of money spread out over a great many years.

Mary then bore Brandon several children, whom we will save for later. During the rise of Anne Boleyn Charles positioned himself as an ally of the Boleyns, while Mary remained loyal to Katherine of Aragon, whom by now she had known, and thought of as a sister-in-law, for almost thirty years. Because Mary did not want to recognize Anne as queen in the etiquette of the court, she stayed away at the Suffolks' estates. Brandon, for whom proximity to the king was indispensable, stayed. Mary grew sick with cancer while Brandon was assisting Henry VIII with Anne Boleyn's coronation, and died that summer.

In 1528, while Brandon and Mary was still married, Henry VIII had given Brandon the wardship of one Katherine Willoughby. Brandon planned to marry Willoughby to his own heir. But once Mary died, he decided to marry Willoughby himself, waiting all of three months after Mary died. He was 49, she was 14. With her he had more children.

Also, at Mary Tudor's funeral, apparently the first two Brandon daughters were unhappy that they held a lower place of respect than Brandon's children by the queen, so there was something of an undignified shoving match.

Finally, around the time Brandon himself died in 1545 Henry was growing dissatisfied with his queen at the time, Katherine Parr. He considered Willoughby as a potential queen #7. After Henry VIII died, Parr herself remarried, to Thomas Seymour. Parr then died herself in childbed with Seymour's daughter, who was given to Katherine Willoughby to raise, since they were actually good friends.

Katherine Willoughby was known not just for her beauty, but for her learning, piety and fierce Protestantism.

Now in our timeline, not only Brandon's sons by Mary Tudor, but his sons by Katherine Willoughby who could continue the Suffolk title, die out. This is probably a good place to leave things, since it is these deaths where the timeline starts to play with the fortunes of the Brandon family.

What I would leave you all with is this: in the world of the timeline the Brandons, the timeless and eternal royal family of England, are known for their piety, fidelity and above all, their moral integrity.

Below, a projected Monument to British Heroes, 19th century, as The William Brandon Monument at Bosworth

Last edited:

Oh, one last note about Brandon: there may have been some legal imperfections in Brandon's annulment of Margaret Mortimer (wife #1, if we're not counting the pre-contract with Anne Browne). Anyway, during the 1520's he had to apply to the pope for a new annulment sufficient to clear away any uncertainties. Since Margaret Mortimer was still alive, if their marriage was still effective as of the time he married Mary Tudor, that second marriage would be null. Which would mean he had defiled the King of England's sister and the widow of a King of France. Apparently it was a few years into the marriage before this even crossed his mind.

The Life of the Elector Friedrich IV, Saxony, 1525-1534

The Days of Nit Kopf Ab, from The Heresiarchs, by Sigismunda Killinger & Lise Freitag (1987)

In 1525, Georg, the Albertine duke of Saxony, mentioned for the first time the possibility that the Ernestine Wettins’ support of Luther and his reforms might lose them the electoral dignity. In those turbulent years, such a notion could be seen as fanciful: following his election as emperor, Charles V had returned to Spain leaving behind a regency council to run the Empire in his absence. This regency council had included the Saxon Elector Friedrich III, whose support had been necessary to Charles’s election, and after Friedrich’s death would include his brother the Elector Johann, who also contributed to the defeat of the rebellious peasants at Frankenhausen.

During these same years, Charles V faced an endless series of crises across his other realms: rebellion in Spain, the effort of Francois I to overrun Italy, the chaotic relationship with a pope endlessly trying to build alliances to serve as a diplomatic counterweight to excessive Habsburg power, and the invasion of Hungary by the Ottomans being just the most pressing. Though the Habsburgs frequently made broad statements during this time about the necessity of stamping out heresy and repairing the unity of the church, undertaking that in the face of so much other instability seemed, both to themselves and the Reform-minded princes of Germany, a lethal overreach.

So it was hardly coincidental Charles returned to Germany to face the Lutheran threat in 1530. Francois I had been taken prisoner at Pavia, humiliating terms imposed upon him and his sons and heirs exchanged as hostages for him. Clement VII had been shown the consequences of his defiance in the horrendous Sack of Rome, and had subsequently personally crowned Charles V at Bologna. Even the Ottoman menace had for the moment abated. With his rule settled and his power secure, Charles V showed at the Diet of Augsburg a different face than he had previously.

For his part, the Elector Johann found this change bracing. In their personal meetings at Augsburg, Charles informed Johann that he might have his own succession to the electoral dignity challenged, and moreover, might have his younger son’s marriage to Sybille of Cleves declared invalid. A man of sixty, well versed with the procedural hurdles the emperor would have to surmount to do any of this, Johann was not easily frightened by these threats. He was more annoyed by the decision to dispense with the regency council, which he and the other reform-minded princes had used to prevent the re-imposition of orthodoxy, and instead elect a new King of the Romans, who in addition to serving as the heir-apparent to the emperor would be able to administer and execute the emperor’s policies in a more expedited fashion. The emperor’s choice for this role of his younger brother Ferdinand, now the king of Bohemia and Hungary, hardly put the Protestant princes at ease.

The Diet of Augsburg ended in disarray, with no resolution to the religious question. Enraged, Charles V reverted to the terms of the 1521 Edict of Worms, whereby he declared it illegal to support or defend Luther, or to interact with Luther in any way other than to capture him and convey him to the emperor’s authority. Catholicism was restored as the state religion of all the German lands, all property and legal authority were restored to the bishops, and any prince resisting these terms would be brought to justice. All these provisions were codified as the Recess of Augsburg, issued by Charles on November 22, 1530.

The response to the Recess was quick. A month later the Protestant princes met at Schmalkald, a Hessian town in Thuringia near the Saxon border, and on December 31 the League of Schmalkald was formed, consisting of Electoral Saxony, Hesse, Anhalt, Braunschweig, Mansfeld, and the imperial cities of Magdeburg and Bremen. Over the course of 1531 the Schmalkaldic League expanded to include the imperial cities of Strassburg, Konstanz, Memmingen, Lindau, Luebeck, Gottingen and Ulm. The co-leaders of the League were Johann of Saxony and Philip II, Landgrave of Hesse. Realizing that if Ferdinand were recognized as King of the Romans Charles V would be better able to enforce the terms of the Recess, Johann decided to strenuously oppose his election.

Thus Johann sent his son Friedrich to meet Charles at Cologne with a set of legal protests against Ferdinand becoming King of the Romans. This proved to be a miserable failure, and Ferdinand was the choice of the other six electors when they voted January 6. For Saxony, the only silver lining of Cologne was that the electors decided not to formally strip Johann of his vote, on account of his separation from the Christian church. On January 8 Ferdinand was crowned King of the Romans, and immediately declared his intent to implement the Recess of Augsburg. Virtually the only actual positive development for the Schmalkaldic League in 1531 was the fact that the dukes of Bavaria, still smarting over their defeat by Ferdinand in the election to be kings of Bohemia five years earlier, allowed their dynastic rivalry with the Habsburgs to overcome their religious loyalties, and they entered into an alliance with the League.

By now, Johann’s health was failing. Increasingly, matters fell to his son the Duke Friedrich. For the Wettins the next diplomatic success came in the summer of 1532, when at Kloster Zevern, the German states of Saxony, Bavaria and Hesse entered into an alliance with France, which had as its goal sewing unrest against Ferdinand as the King of the Romans. An unofficial fifth party to the alliance was the Hungarians under Zapolya. At the same time, for unrelated reasons, the Habsburgs’ efforts to make a peace with the Ottomans that would enable them to focus their resources against the Protestant princes of Germany fell through. Instead, Suleiman demanded the surrender of the Habsburgs’ Hungarian lands.

As quickly as matters had reached an absolute crisis for the Saxons, they now moved the other direction. Ferdinand begged Charles to relent in his policy toward the Protestant princes so the Empire could be united against the Ottomans. With the Archbishop of Mainz and the Count Palatine acting as mediators, in August 1532 a peace was reached among the German princes at Nuremberg. By its terms, the Lutherans would be free to observe and preach the tenets they had declared to the world in the Diet at Augsburg, they could keep the Church property they already held, and that the jurisdiction of the imperial courts would not apply to cases of religion. In return the Lutherans were obligated to not offer succor to Zwinglians and Anabaptists, and to provide assistance in the war against the Ottomans. These terms would last until either the next imperial diet or a General Council of the Catholic Church.

Virtually at the same time the peace of Nuremberg was reached, the Elector Johann died. The co-leader of the Schmalkaldic League, Philip of Hesse, rejected the peace partly because it would prevent the acquisition of new church lands by the Protestant princes, but also because he was more closely aligned with the branches of Protestant thought proscribed by the peace. Philip, who had succeeded his father as landgrave while still a boy, had been raised at the court of the Saxon electors, and had been something of an elder brother to the Duke Friedrich, who now on his father’s death was the Elector Friedrich IV. The younger Friedrich had been closely involved in negotiating the Peace of Nuremberg, but some believed this was only to allay suspicions in his own Lutheran religious orthodoxy until after his father had died, and that his more natural leanings were with Philip of Hesse.

Instead, Friedrich moved decisively to signify his allegiance to the emperor and promptly sent a force to aid against the Turks. And just as he led the Saxon forces dispatched to defend Vienna in 1527, now he sent his heir, presently Johann the Younger. For his own part, Friedrich used the respite the Habsburgs’ renewed troubles with the Ottomans provided to its utmost. In 1532 Friedrich had found Henry VIII’s ambassador to the court of the Holy Roman Emperor, one Thomas Cranmer, sympathetic to his cause. They formed a friendship, and when Cranmer was elevated by Henry to the position of Archbishop of Canterbury Friedrich IV found Cranmer gave him the means to exploit English diplomatic isolation. In 1533 Friedrich IV and his mother were invited to England.

Electoral Saxony was still in sufficient danger that Friedrich decided against making his journey public. Instead, he disseminated the story that he was spending the summer hunting in his lodge at Annaberg, and that his mother, having fallen out with him, had been returned to her jail at the Wartburg. Traveling incognito by way of Hamburg, they had been in England a month by the time their absence in Saxony was discovered. In Friedrich IV’s absence, Johann the Younger was made regent. While the bond of trust between the brothers was strong, Friedrich IV nonetheless took the measure of sending Johann the Younger’s own son, little more than an infant, to live with Philip of Hesse for the duration of his time away. The word hostage was not used, but it did not have to be.

In England, Henry and Friedrich found each other ready partners in transacting significant deals: Friedrich relinquished his place in the English succession, swore to uphold Henry’s choice in the matter, and got for his trouble a large annual subsidy. Both the King of England and the Elector of Saxony agreed to aid each other in the event of an attack by the Emperor. Finally, a marital alliance was concluded, albeit not the most impressive one, as the elector’s sister Katarina was betrothed to the king’s other nephew, Henry Brandon, the Earl of Lincoln. Collectively known as the Treaty of Windsor, these arrangements broke through decades of antipathy between Henry VIII and the Lutherans, and between Henry VIII and Friedrich’s mother. It was far more significant for the Saxons in every way than the deal reached at Kloster Zevern, in which the Protestant princes were really only incidental to a much deeper alliance between the Catholic powers of France and Bavaria.

When Friedrich IV returned from England in January 1534 he had pulled off a diplomatic coup. Charles could not move against the Schmalkaldic League without threatening to draw in one of the great powers of northwest Europe. The idea of a localized war, in which the Habsburgs could leverage their possessions and resources across Europe to overwhelm scattered resistance among parochial princes, which loomed so large two years before, now seemed fanciful.

Friedrich however still needed a consort, and he needed more security for his rule than could be found on the shifting sands of European alliance politics. The Princess Dorothea of Denmark, herself the daughter of Charles V’s sister, was enthusiastic for the Reformed faith, had a claim to the Danish throne that had a value even if Friedrich did not intend to advance it directly, and most importantly would produce heirs the Habsburgs would be reluctant to move against. Also, crucially, whatever benefits a match with Dorothea might confer on the Wettins, would be a set of inducements the Habsburgs could not confer in their own diplomatic politics.

Charles V had been negotiating to marry Dorothea to the Elector Palatine. If the Elector married Dorothea, he would have a claim through her to the Danish throne. Not only would he himself be bound by marriage to the Habsburgs, but the Habsburgs could use the promise of aid to him in advancing his claim to induce him to vote in their cause in imperial elections and to support their policies in the diets. While inevitably, Friedrich making his own match for Dorothea would create enmity with the Elector Palatine, that friction would not be the same as the unshakeable bond of self-interest the imagined match would create between the Wittelsbachs and the Habsburgs.

Thus Friedrich opened negotiations through Mary of Hungary for Dorothea’s hand, representing himself as having inherited a situation as elector of Saxony far from his liking, and casting himself as a secret Catholic longing for a return to the church. Friedrich secured the marriage to Dorothea on false pretenses, but the terms of his marriage contract were still significant. He promised the return of Saxony to Catholic orthodoxy, the surrender of Luther, and the commencement of an effort to depose the king of Denmark in favor of Dorothea’s claim. Of course, he broke these commitments at the first opportunity. But he also promised to end his protest of Ferdinand’s election as king of the Romans, which crucially meant severing the alliance with Bavaria and France.

Even as he faced the most histrionic protests from the emissaries of the Emperor and the King of the Romans in late 1534 over his “rape by fraud” of the Princess Dorothea, Friedrich offered to continue to recognize Ferdinand as King of the Romans. Moreover, he made a new overture to Ferdinand: he would permit freedom of worship to his subjects who wished to remain in the Catholic Church, reversing a policy of his father’s, so long as Ferdinand permitted his Lutheran subjects the same liberty. Moreover, he would decline to offer state support for any Lutheran proselytizing in Habsburg lands, if likewise Ferdinand refrained from the same with respect to Electoral Saxony. Finally, at Ferdinand’s insistence, Friedrich also relented and officially repressed the Anabaptist and Sacramentarian reformists. The king and elector’s representatives sealed the substance of this arrangement at Dohna, on the Elbe near the border of Saxony and Bohemia.

If Ferdinand’s willingness to decline to make war against Saxony over the insult of the marriage to Dorothea seems unreasonable to our eyes, it needs to be remembered his own religious situation was unstable, not merely in Bohemia and Hungary, but even in Austria, where the reformers had made illicit inroads. From his perspective, the situation following the Concessions of Dohna represented both less than what he had hoped he would get by marrying Dorothea into the Ernestine Wettins, and more than what he had had before, with himself recognized as king, the pernicious alliance between the Protestants and France broken, and curbs in place on how far the Saxons would buck religious orthodoxy.

Of course, even now Friedrich was dishonest: while his belief in religious license made the grant of freedom of worship to his Catholic subjects only too easy for him, he had no intention of withholding the same freedom from his more radical Protestant subjects whose beliefs so closely mirrored his own mentor, Karlstadt, and moreover, he accelerated, rather than withheld, efforts to spread the new beliefs in Bohemia and Austria. Friedrich was sure, as his surviving letters attest, that repression of the Lutherans by force of arms would be inevitable. As far as he was concerned, especially until Dorothea bore an heir, and that heir was old enough to be confirmed in his belief in the reformed church, all he had done was buy himself and Saxony time. He intended to use that time to the utmost.

Dorothea of Denmark, Electress Palatine by Michael Coxcie as Dorothea of Denmark, Electress of Saxony

In 1525, Georg, the Albertine duke of Saxony, mentioned for the first time the possibility that the Ernestine Wettins’ support of Luther and his reforms might lose them the electoral dignity. In those turbulent years, such a notion could be seen as fanciful: following his election as emperor, Charles V had returned to Spain leaving behind a regency council to run the Empire in his absence. This regency council had included the Saxon Elector Friedrich III, whose support had been necessary to Charles’s election, and after Friedrich’s death would include his brother the Elector Johann, who also contributed to the defeat of the rebellious peasants at Frankenhausen.

During these same years, Charles V faced an endless series of crises across his other realms: rebellion in Spain, the effort of Francois I to overrun Italy, the chaotic relationship with a pope endlessly trying to build alliances to serve as a diplomatic counterweight to excessive Habsburg power, and the invasion of Hungary by the Ottomans being just the most pressing. Though the Habsburgs frequently made broad statements during this time about the necessity of stamping out heresy and repairing the unity of the church, undertaking that in the face of so much other instability seemed, both to themselves and the Reform-minded princes of Germany, a lethal overreach.

So it was hardly coincidental Charles returned to Germany to face the Lutheran threat in 1530. Francois I had been taken prisoner at Pavia, humiliating terms imposed upon him and his sons and heirs exchanged as hostages for him. Clement VII had been shown the consequences of his defiance in the horrendous Sack of Rome, and had subsequently personally crowned Charles V at Bologna. Even the Ottoman menace had for the moment abated. With his rule settled and his power secure, Charles V showed at the Diet of Augsburg a different face than he had previously.

For his part, the Elector Johann found this change bracing. In their personal meetings at Augsburg, Charles informed Johann that he might have his own succession to the electoral dignity challenged, and moreover, might have his younger son’s marriage to Sybille of Cleves declared invalid. A man of sixty, well versed with the procedural hurdles the emperor would have to surmount to do any of this, Johann was not easily frightened by these threats. He was more annoyed by the decision to dispense with the regency council, which he and the other reform-minded princes had used to prevent the re-imposition of orthodoxy, and instead elect a new King of the Romans, who in addition to serving as the heir-apparent to the emperor would be able to administer and execute the emperor’s policies in a more expedited fashion. The emperor’s choice for this role of his younger brother Ferdinand, now the king of Bohemia and Hungary, hardly put the Protestant princes at ease.

The Diet of Augsburg ended in disarray, with no resolution to the religious question. Enraged, Charles V reverted to the terms of the 1521 Edict of Worms, whereby he declared it illegal to support or defend Luther, or to interact with Luther in any way other than to capture him and convey him to the emperor’s authority. Catholicism was restored as the state religion of all the German lands, all property and legal authority were restored to the bishops, and any prince resisting these terms would be brought to justice. All these provisions were codified as the Recess of Augsburg, issued by Charles on November 22, 1530.

The response to the Recess was quick. A month later the Protestant princes met at Schmalkald, a Hessian town in Thuringia near the Saxon border, and on December 31 the League of Schmalkald was formed, consisting of Electoral Saxony, Hesse, Anhalt, Braunschweig, Mansfeld, and the imperial cities of Magdeburg and Bremen. Over the course of 1531 the Schmalkaldic League expanded to include the imperial cities of Strassburg, Konstanz, Memmingen, Lindau, Luebeck, Gottingen and Ulm. The co-leaders of the League were Johann of Saxony and Philip II, Landgrave of Hesse. Realizing that if Ferdinand were recognized as King of the Romans Charles V would be better able to enforce the terms of the Recess, Johann decided to strenuously oppose his election.

Thus Johann sent his son Friedrich to meet Charles at Cologne with a set of legal protests against Ferdinand becoming King of the Romans. This proved to be a miserable failure, and Ferdinand was the choice of the other six electors when they voted January 6. For Saxony, the only silver lining of Cologne was that the electors decided not to formally strip Johann of his vote, on account of his separation from the Christian church. On January 8 Ferdinand was crowned King of the Romans, and immediately declared his intent to implement the Recess of Augsburg. Virtually the only actual positive development for the Schmalkaldic League in 1531 was the fact that the dukes of Bavaria, still smarting over their defeat by Ferdinand in the election to be kings of Bohemia five years earlier, allowed their dynastic rivalry with the Habsburgs to overcome their religious loyalties, and they entered into an alliance with the League.

By now, Johann’s health was failing. Increasingly, matters fell to his son the Duke Friedrich. For the Wettins the next diplomatic success came in the summer of 1532, when at Kloster Zevern, the German states of Saxony, Bavaria and Hesse entered into an alliance with France, which had as its goal sewing unrest against Ferdinand as the King of the Romans. An unofficial fifth party to the alliance was the Hungarians under Zapolya. At the same time, for unrelated reasons, the Habsburgs’ efforts to make a peace with the Ottomans that would enable them to focus their resources against the Protestant princes of Germany fell through. Instead, Suleiman demanded the surrender of the Habsburgs’ Hungarian lands.

As quickly as matters had reached an absolute crisis for the Saxons, they now moved the other direction. Ferdinand begged Charles to relent in his policy toward the Protestant princes so the Empire could be united against the Ottomans. With the Archbishop of Mainz and the Count Palatine acting as mediators, in August 1532 a peace was reached among the German princes at Nuremberg. By its terms, the Lutherans would be free to observe and preach the tenets they had declared to the world in the Diet at Augsburg, they could keep the Church property they already held, and that the jurisdiction of the imperial courts would not apply to cases of religion. In return the Lutherans were obligated to not offer succor to Zwinglians and Anabaptists, and to provide assistance in the war against the Ottomans. These terms would last until either the next imperial diet or a General Council of the Catholic Church.

Virtually at the same time the peace of Nuremberg was reached, the Elector Johann died. The co-leader of the Schmalkaldic League, Philip of Hesse, rejected the peace partly because it would prevent the acquisition of new church lands by the Protestant princes, but also because he was more closely aligned with the branches of Protestant thought proscribed by the peace. Philip, who had succeeded his father as landgrave while still a boy, had been raised at the court of the Saxon electors, and had been something of an elder brother to the Duke Friedrich, who now on his father’s death was the Elector Friedrich IV. The younger Friedrich had been closely involved in negotiating the Peace of Nuremberg, but some believed this was only to allay suspicions in his own Lutheran religious orthodoxy until after his father had died, and that his more natural leanings were with Philip of Hesse.

Instead, Friedrich moved decisively to signify his allegiance to the emperor and promptly sent a force to aid against the Turks. And just as he led the Saxon forces dispatched to defend Vienna in 1527, now he sent his heir, presently Johann the Younger. For his own part, Friedrich used the respite the Habsburgs’ renewed troubles with the Ottomans provided to its utmost. In 1532 Friedrich had found Henry VIII’s ambassador to the court of the Holy Roman Emperor, one Thomas Cranmer, sympathetic to his cause. They formed a friendship, and when Cranmer was elevated by Henry to the position of Archbishop of Canterbury Friedrich IV found Cranmer gave him the means to exploit English diplomatic isolation. In 1533 Friedrich IV and his mother were invited to England.

Electoral Saxony was still in sufficient danger that Friedrich decided against making his journey public. Instead, he disseminated the story that he was spending the summer hunting in his lodge at Annaberg, and that his mother, having fallen out with him, had been returned to her jail at the Wartburg. Traveling incognito by way of Hamburg, they had been in England a month by the time their absence in Saxony was discovered. In Friedrich IV’s absence, Johann the Younger was made regent. While the bond of trust between the brothers was strong, Friedrich IV nonetheless took the measure of sending Johann the Younger’s own son, little more than an infant, to live with Philip of Hesse for the duration of his time away. The word hostage was not used, but it did not have to be.

In England, Henry and Friedrich found each other ready partners in transacting significant deals: Friedrich relinquished his place in the English succession, swore to uphold Henry’s choice in the matter, and got for his trouble a large annual subsidy. Both the King of England and the Elector of Saxony agreed to aid each other in the event of an attack by the Emperor. Finally, a marital alliance was concluded, albeit not the most impressive one, as the elector’s sister Katarina was betrothed to the king’s other nephew, Henry Brandon, the Earl of Lincoln. Collectively known as the Treaty of Windsor, these arrangements broke through decades of antipathy between Henry VIII and the Lutherans, and between Henry VIII and Friedrich’s mother. It was far more significant for the Saxons in every way than the deal reached at Kloster Zevern, in which the Protestant princes were really only incidental to a much deeper alliance between the Catholic powers of France and Bavaria.

When Friedrich IV returned from England in January 1534 he had pulled off a diplomatic coup. Charles could not move against the Schmalkaldic League without threatening to draw in one of the great powers of northwest Europe. The idea of a localized war, in which the Habsburgs could leverage their possessions and resources across Europe to overwhelm scattered resistance among parochial princes, which loomed so large two years before, now seemed fanciful.

Friedrich however still needed a consort, and he needed more security for his rule than could be found on the shifting sands of European alliance politics. The Princess Dorothea of Denmark, herself the daughter of Charles V’s sister, was enthusiastic for the Reformed faith, had a claim to the Danish throne that had a value even if Friedrich did not intend to advance it directly, and most importantly would produce heirs the Habsburgs would be reluctant to move against. Also, crucially, whatever benefits a match with Dorothea might confer on the Wettins, would be a set of inducements the Habsburgs could not confer in their own diplomatic politics.

Charles V had been negotiating to marry Dorothea to the Elector Palatine. If the Elector married Dorothea, he would have a claim through her to the Danish throne. Not only would he himself be bound by marriage to the Habsburgs, but the Habsburgs could use the promise of aid to him in advancing his claim to induce him to vote in their cause in imperial elections and to support their policies in the diets. While inevitably, Friedrich making his own match for Dorothea would create enmity with the Elector Palatine, that friction would not be the same as the unshakeable bond of self-interest the imagined match would create between the Wittelsbachs and the Habsburgs.

Thus Friedrich opened negotiations through Mary of Hungary for Dorothea’s hand, representing himself as having inherited a situation as elector of Saxony far from his liking, and casting himself as a secret Catholic longing for a return to the church. Friedrich secured the marriage to Dorothea on false pretenses, but the terms of his marriage contract were still significant. He promised the return of Saxony to Catholic orthodoxy, the surrender of Luther, and the commencement of an effort to depose the king of Denmark in favor of Dorothea’s claim. Of course, he broke these commitments at the first opportunity. But he also promised to end his protest of Ferdinand’s election as king of the Romans, which crucially meant severing the alliance with Bavaria and France.

Even as he faced the most histrionic protests from the emissaries of the Emperor and the King of the Romans in late 1534 over his “rape by fraud” of the Princess Dorothea, Friedrich offered to continue to recognize Ferdinand as King of the Romans. Moreover, he made a new overture to Ferdinand: he would permit freedom of worship to his subjects who wished to remain in the Catholic Church, reversing a policy of his father’s, so long as Ferdinand permitted his Lutheran subjects the same liberty. Moreover, he would decline to offer state support for any Lutheran proselytizing in Habsburg lands, if likewise Ferdinand refrained from the same with respect to Electoral Saxony. Finally, at Ferdinand’s insistence, Friedrich also relented and officially repressed the Anabaptist and Sacramentarian reformists. The king and elector’s representatives sealed the substance of this arrangement at Dohna, on the Elbe near the border of Saxony and Bohemia.

If Ferdinand’s willingness to decline to make war against Saxony over the insult of the marriage to Dorothea seems unreasonable to our eyes, it needs to be remembered his own religious situation was unstable, not merely in Bohemia and Hungary, but even in Austria, where the reformers had made illicit inroads. From his perspective, the situation following the Concessions of Dohna represented both less than what he had hoped he would get by marrying Dorothea into the Ernestine Wettins, and more than what he had had before, with himself recognized as king, the pernicious alliance between the Protestants and France broken, and curbs in place on how far the Saxons would buck religious orthodoxy.

Of course, even now Friedrich was dishonest: while his belief in religious license made the grant of freedom of worship to his Catholic subjects only too easy for him, he had no intention of withholding the same freedom from his more radical Protestant subjects whose beliefs so closely mirrored his own mentor, Karlstadt, and moreover, he accelerated, rather than withheld, efforts to spread the new beliefs in Bohemia and Austria. Friedrich was sure, as his surviving letters attest, that repression of the Lutherans by force of arms would be inevitable. As far as he was concerned, especially until Dorothea bore an heir, and that heir was old enough to be confirmed in his belief in the reformed church, all he had done was buy himself and Saxony time. He intended to use that time to the utmost.

Dorothea of Denmark, Electress Palatine by Michael Coxcie as Dorothea of Denmark, Electress of Saxony

Last edited:

The Life of the Elector Friedrich IV: Supplemental Note, Friedrich's Goals

Sigismunda Killinger, from her Opening Remarks at the St. James University Public Conference, "Uncle and Nephew: The Treaty of Windsor at 450 Years" (1983)

Is the simulmission working? Good. Let's begin.

There has been a retrospective and triumphalist tendency in the scholarship to say Friedrich IV went to England, saw Windsor, saw Richmond Palace, saw, really the splendor of the late medieval kingdom, and decided he must have one of his own. And dates the project of the German Second Realm from that moment.

Several problems with this: not least, the project of the Elector Friedrich IV is not that of Christian I. Friedrich's reign lay not at the end of the long twilight struggle, but at its beginning. In his time there was not the sense that imperial institutions had been exhausted, their guarantees and procedural rights destroyed, the polity of the empire broken beyond compare [sic]. To our best awareness, Friedrich was not unhappy with the empire, or even with the state of imperial institutions apart from their perceived misuse by the Habsburgs.

It is likewise a mistake to assume, even given his association with von Hutten, Friedrich desired a consolidation of imperial power. Such in fact gets his program with respect to the political life of the princely states within the empire backward. He wanted stronger princely states, not weaker ones, greater guarantees against centralized authority, not the creation of a post-feudal monarchy on the English model.

And while no doubt he would not have turned down an offer of the imperial throne, who would? he did not covet it to our knowledge. It is easy to assume, because he was a man willing to rebel against the Church of the time, to challenge even the Lutheran beliefs championed by his family, and to countenance ideas of freedom of observance and expression, that he was otherwise a prophet of the modern state. Yet Friedrich would have been content to see the constitutional system of the Holy Roman Empire he was born into continue forever.

Rather than an innovator, he saw himself as a defender of German imperial tradition against innovation, specifically against what he saw as the tyrannical influence of the House of Habsburg, and what he saw as the tyrannical and corruptive influence of their economic and military power on that tradition.

We are free to think about it as a paradox that a prince so deeply embedded in the most radical change of religion to strike central Europe since Christianization itself saw himself as a conservative, but that nonetheless describes his self-perception.

This is in fact one reason why his Friedrich's policies are to our eyes so transactional. They are not meant to synthesize, to create new political structures, to replace what those who came after him, but not Friedrich himself, would think of as a failed system. He saw himself, certainly not without reason considering the power aligned against him, as only ever one step ahead of checkmate, as improvising for survival. Not transformation. Certainly not even conquest. Though, once again, he did not turn the chance down when it presented itself.

And that is why I would say if any contemporary prince provided an example to Friedrich, it would actually be not Henry Tudor, though I hope it does not dismay the organizers of this lovely gathering for me to say that. It is instead Francis I, who had by the time Friedrich came to power been engaged in his own closely fought chess match against Charles V for the better part of twenty years, outwitting him by diplomacy and even outright deception when he could not triumph by force.

What Friedrich realized about Henry was how inapposite their circumstances were. As he wrote in a letter from 1535, "the fairest part of that country by my light is not the castles its kings built, but the moat around it that God built. Would I had one for my own."

Is the simulmission working? Good. Let's begin.

There has been a retrospective and triumphalist tendency in the scholarship to say Friedrich IV went to England, saw Windsor, saw Richmond Palace, saw, really the splendor of the late medieval kingdom, and decided he must have one of his own. And dates the project of the German Second Realm from that moment.

Several problems with this: not least, the project of the Elector Friedrich IV is not that of Christian I. Friedrich's reign lay not at the end of the long twilight struggle, but at its beginning. In his time there was not the sense that imperial institutions had been exhausted, their guarantees and procedural rights destroyed, the polity of the empire broken beyond compare [sic]. To our best awareness, Friedrich was not unhappy with the empire, or even with the state of imperial institutions apart from their perceived misuse by the Habsburgs.

It is likewise a mistake to assume, even given his association with von Hutten, Friedrich desired a consolidation of imperial power. Such in fact gets his program with respect to the political life of the princely states within the empire backward. He wanted stronger princely states, not weaker ones, greater guarantees against centralized authority, not the creation of a post-feudal monarchy on the English model.

And while no doubt he would not have turned down an offer of the imperial throne, who would? he did not covet it to our knowledge. It is easy to assume, because he was a man willing to rebel against the Church of the time, to challenge even the Lutheran beliefs championed by his family, and to countenance ideas of freedom of observance and expression, that he was otherwise a prophet of the modern state. Yet Friedrich would have been content to see the constitutional system of the Holy Roman Empire he was born into continue forever.

Rather than an innovator, he saw himself as a defender of German imperial tradition against innovation, specifically against what he saw as the tyrannical influence of the House of Habsburg, and what he saw as the tyrannical and corruptive influence of their economic and military power on that tradition.

We are free to think about it as a paradox that a prince so deeply embedded in the most radical change of religion to strike central Europe since Christianization itself saw himself as a conservative, but that nonetheless describes his self-perception.

This is in fact one reason why his Friedrich's policies are to our eyes so transactional. They are not meant to synthesize, to create new political structures, to replace what those who came after him, but not Friedrich himself, would think of as a failed system. He saw himself, certainly not without reason considering the power aligned against him, as only ever one step ahead of checkmate, as improvising for survival. Not transformation. Certainly not even conquest. Though, once again, he did not turn the chance down when it presented itself.

And that is why I would say if any contemporary prince provided an example to Friedrich, it would actually be not Henry Tudor, though I hope it does not dismay the organizers of this lovely gathering for me to say that. It is instead Francis I, who had by the time Friedrich came to power been engaged in his own closely fought chess match against Charles V for the better part of twenty years, outwitting him by diplomacy and even outright deception when he could not triumph by force.

What Friedrich realized about Henry was how inapposite their circumstances were. As he wrote in a letter from 1535, "the fairest part of that country by my light is not the castles its kings built, but the moat around it that God built. Would I had one for my own."

Last edited:

The Life of Elector Friedrich IV, Holy Roman Empire, 1526-42

"The Road to Dueren", from Outlaw Saxony: New Perspectives on the Sechszentes Jahrhundert Empire by Louis Hadrami

No sooner had the Turkish menace abated in the east but Charles V found himself embroiled in a fresh conflict in Germany. Some decades prior, Duke Ulrich of Wurttemburg, formerly a friend of the emperor Maximilian, had murdered one of his knights to take his wife for himself, alienated his commons with extortionate taxation, faced extensive revolts, and been driven from power by the Swabian League. The League then sold Wurttemberg to the Habsburgs. At the height of the Great Peasants Revolt, Ulrich had returned to power as “Ulrich the Peasant” only to be evicted again. In 1526 he gained the support of Philip, Landgrave of Hesse. During his long years of exile, Ulrich had been reduced to brigandage and mercenary work, some of it for France. Thus, he had little trouble procuring French assistance for the project of recovering his patrimony, albeit through a legal fiction and the intermediary of Hesse so that Francois I did not violate his fragile peace treaty with Charles V.