You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Araldyana - Rome in the West

- Thread starter Pischinovski

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

II.II. Zenith

II.II. Zenith

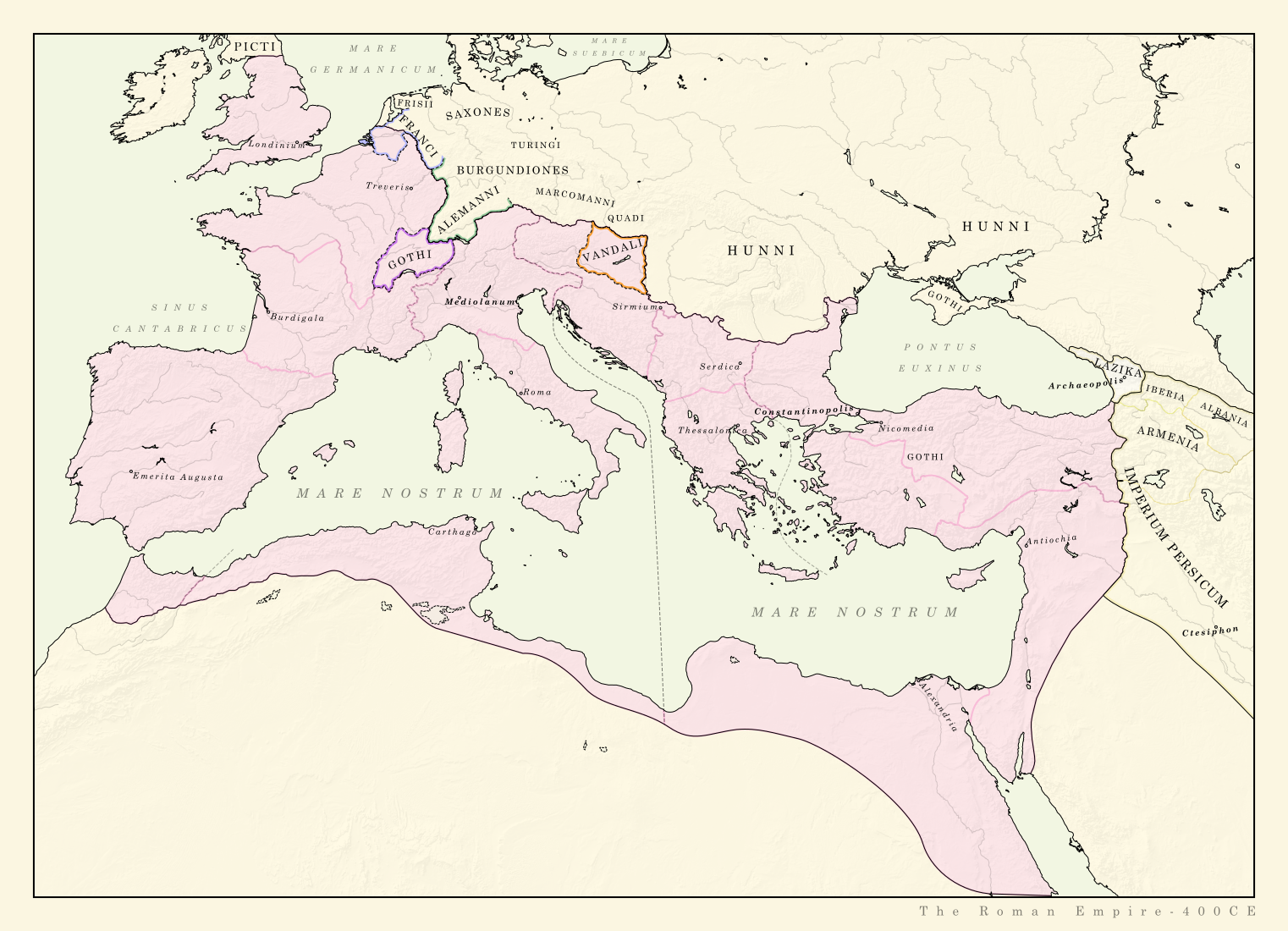

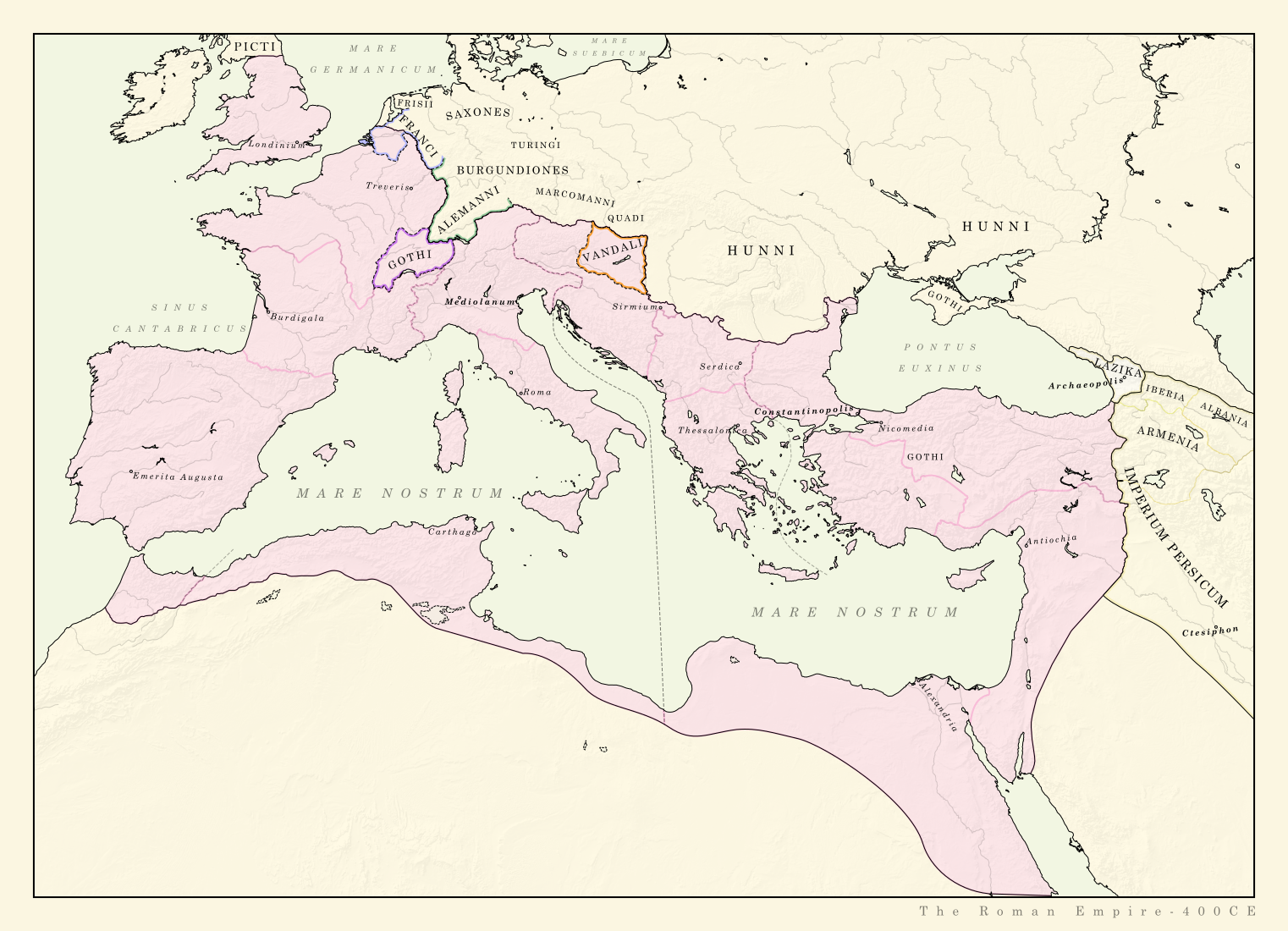

Following the war against Gaudentius the Eastern chamberlain Eutropius reached the zenith of his career. He had not only cemented his position as the power behind the Eastern throne but also succeeded in establishing himself as regent for the adolescent Western emperor Honorius. Eutropius, who was a man of the bureaucracy, based his influence in the West on two things. Firstly, the fragmentation of the once mighty military office magister utriusque militiae praesentalis, which was abolished in favor of four lesser magistri following the fall of Gaudentius, hitherto the last magister praesentalis. No single general could anymore wield the whole military power of the West. Secondly, Eutropius promoted his friends and allies and gave them key positions in the Western administration and military, while also pitching them against one another and making himself the abider of the subsequent conflicts.

The chamberlain’s strategy of divide and rule intermixed with nepotism was most obvious in the prefecture of Italia, which also encompassed Noricum and carthaginian Africa. Eutropius arranged for his friend Leo to become one of the two magistri of Italia. Leo, a mediocre commander at best, had his good relations with Eutropius to thank for his position and was short on supporters of his own. During the war for the West Leo had been overshadowed by Alaric, a far more capable commander. After the war Alaric was appointed magister for the Gallian prefecture, including Hispania and Britannia, where he had to share power with Jacobus, previously one of the duces [plural of “dux”] at the Germanic border.

Leo’s colleague as magister of Italia was the mighty berber general Gildo. Gildo, formerly ‘only’ the commander of Africa, had cast his lot with Eutropius at the beginning of the war and was awarded with the co-command of the Italian prefecture after Gaudentius’ downfall. Unlike Leo, Gildo had a power base of his own, namely the provinces of Africa, and had recently put down a revolt by his brother, squashing the last resistance to his rule in the process. The African commander was on friendly terms with Eutropius, but unlike Leo he was not dependent on the chamberlain’s mercy. In fact Gildo might not have eclipsed Eutropius in terms of power but as the scion of Berber royalty and distant in-law of the imperial house through his daughter, he surely surpassed the slave-turned-regent in matters of prestige. To assure himself of Gildo’s loyalty Eutropius, in the role of Honorius’ guardian, allowed Gildo to choose his successor as comes africae and subsequently gave the comes the prerogative to appoint subordinate officers. As a further sign of goodwill Eutropius allowed for Gildo’s daughter Salvina to return to her father’s domain from her forced exile in Constantinopolis.

In theory Leo and Gildo were to have equal authority but in practice Gildo governed his African home provinces unchallenged. This arrangement seemed to work out just fine for Eutropius: Gildo remained a valuable ally while Leo would be the chamberlain’s representative in the West and counterbalance Gildo’s ambitions. While both Gildo and Leo were generally well-disposed towards Eutropius, it became soon apparent that they disliked each other, which was something the chamberlain had anticipated and hoped would further strengthen his grip on the West.

Following the war against Gaudentius the Eastern chamberlain Eutropius reached the zenith of his career. He had not only cemented his position as the power behind the Eastern throne but also succeeded in establishing himself as regent for the adolescent Western emperor Honorius. Eutropius, who was a man of the bureaucracy, based his influence in the West on two things. Firstly, the fragmentation of the once mighty military office magister utriusque militiae praesentalis, which was abolished in favor of four lesser magistri following the fall of Gaudentius, hitherto the last magister praesentalis. No single general could anymore wield the whole military power of the West. Secondly, Eutropius promoted his friends and allies and gave them key positions in the Western administration and military, while also pitching them against one another and making himself the abider of the subsequent conflicts.

The chamberlain’s strategy of divide and rule intermixed with nepotism was most obvious in the prefecture of Italia, which also encompassed Noricum and carthaginian Africa. Eutropius arranged for his friend Leo to become one of the two magistri of Italia. Leo, a mediocre commander at best, had his good relations with Eutropius to thank for his position and was short on supporters of his own. During the war for the West Leo had been overshadowed by Alaric, a far more capable commander. After the war Alaric was appointed magister for the Gallian prefecture, including Hispania and Britannia, where he had to share power with Jacobus, previously one of the duces [plural of “dux”] at the Germanic border.

Leo’s colleague as magister of Italia was the mighty berber general Gildo. Gildo, formerly ‘only’ the commander of Africa, had cast his lot with Eutropius at the beginning of the war and was awarded with the co-command of the Italian prefecture after Gaudentius’ downfall. Unlike Leo, Gildo had a power base of his own, namely the provinces of Africa, and had recently put down a revolt by his brother, squashing the last resistance to his rule in the process. The African commander was on friendly terms with Eutropius, but unlike Leo he was not dependent on the chamberlain’s mercy. In fact Gildo might not have eclipsed Eutropius in terms of power but as the scion of Berber royalty and distant in-law of the imperial house through his daughter, he surely surpassed the slave-turned-regent in matters of prestige. To assure himself of Gildo’s loyalty Eutropius, in the role of Honorius’ guardian, allowed Gildo to choose his successor as comes africae and subsequently gave the comes the prerogative to appoint subordinate officers. As a further sign of goodwill Eutropius allowed for Gildo’s daughter Salvina to return to her father’s domain from her forced exile in Constantinopolis.

In theory Leo and Gildo were to have equal authority but in practice Gildo governed his African home provinces unchallenged. This arrangement seemed to work out just fine for Eutropius: Gildo remained a valuable ally while Leo would be the chamberlain’s representative in the West and counterbalance Gildo’s ambitions. While both Gildo and Leo were generally well-disposed towards Eutropius, it became soon apparent that they disliked each other, which was something the chamberlain had anticipated and hoped would further strengthen his grip on the West.

II.III. Consuls and Kings

II.III. Consuls and Kings

Modern OTL image of Mtskheta the capital of 5th century Iberia. © Wikimedia:User Doron, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike

For those who aspired to fame and glory the consulship was still a great achievement but the office had lost most of the political power, that has once been associated with it. It was was still extremely prestigious and a matter of public interest. Eutropius ascension to consulship in 399 had led to outrage, as many perceived a eunuch to be unworthy of this office. Had it not been for the resounding victory in the war for West, this could have caused his downfall. Eutropius was a man of increasing arrogance, who created enemies as he went, but he was also capable, cunning and ruthless - qualities that would help him hold on to the immense power he concentrated in his hands.

The consulship was in those years regularly awarded to imperial favourites, as a special honour, or simply occupied by the emperor himself to celebrate anniversaries or important events. The year 400 was no exception as the Western consulship was awarded to Leo, who had Eutropius to thank for it, and the Eastern consulship was occupied by emperor Arcadius, to celebrate the birth of his son Theodosius (called “the younger”) the year prior. Leo was no imbecile, even if Alaric’s favorite poet Claudianus likes to paint him this way, but he lacked the crucial qualities of that enabled Eutropius to rule as effective as he did. The chamberlain was well aware of that as he did never intend for Leo to be his equal. As his subordinate Leo was to act independently but in accordance with Eutropius’ policies, a task he soon showed to be incapable; not because he lacked the will but the cunning.

The seeds of Leo’s troubled career in the West were laid immediately after the end of the war for Italia. Soon after he was appointed magister for the Italian prefecture in the summer of 398, he had pushed for a quick reconstruction of the Adriatic navy which had suffered heavily in the last war. Leo’s initiative had been approved by Eutropius, but the chamberlain was unwilling to commit Eastern funds to the Adriatic navy, which he regarded as a secondary issue as best, leaving the matter of finance to the Western court. Without financial backing from the Eastern court and with a Western administration in disarray Leo had to postpone his plans for the navy and focused instead on the Italian peninsula’s Alpine defense. The office of comes italiae was established on his initiative and with the approval of Eutropius and Leo’s colleague Gildo. The dux was to survey and improve the fortifications of the eastern Alpine passes, which had fallen all too easily in the last war. Gildo put forward his own son-in-law, Nebridius the husband of Salvina, for the position, which was vetoed by Leo and subsequently denied by Eutropius, who as emperor Honorius’ regent had the last say in the appointment of military officials. Instead Bathanarius, a close acquaintance of the late Stilicho and popular with the army, received the office. Stilicho was held in high esteem by the Western soldiery, especially because his immediate successors had let the West in a profound crisis, that many believed Stilicho would have avoided. By installing Bathanarius, who had kept a low profile during the war, Leo wanted to improve his standing with the army of Italia. The choice of Bathanarius was welcomed by many common soldiers but Leo had still difficulties winning their affection and support. His poor performance on the battlefield, his extravagancy and his plump appearance made him the target of mockery and ridicule. Despite his honest attempts to improve the state of the Italian military, he was perceived as incompetent, selfish and out of touch with the soldiery. His poor diplomatic skills did not help either and would contribute to his eventual downfall.

Bathanarius in the meantime proved to be a good choice as he immediately set out to survey the Alpine passes, a enterprise that went on for the remainder of 398 and 399 before being concluded in the first weeks of 400 - the year of Leo’s consulship. The recently appointed consul set his eyes towards the reconstruction of the Adriatic navy but the year began with a disappointment: Eutropius showed himself once again unwilling to commit Eastern funds to the Adriatic navy and merely gave Leo the permission to use Western funds as he saw fit. Western resources were limited, especially because the important Illyrian provinces had been transferred to the East after the war, which had further diminished Western tax revenue. Amidst such monetary problems many at the court viewed the reconstruction of the Adriatic navy as an unnecessary pet project and were opposed to it. But as Leo had received Eutropius’ permission, which meant imperial permission, to use funds as he saw fit, he believed it to be superfluous to listen to courtly objections. The consul might have been successful with that tactic would it have not been for his colleague Gildo, who denied him support and even actively obstructed his plans. Gildo, who treated the African fleet like his personal property, had no interest in the resurrection of an potential adversary. Additionally the African commander disliked Leo on a personal level. Ever since his son-in-law Nebridius was denied the comitatus italiae in favour of Bathanarius Gildo would oppose Leo wherever possible as he saw him as a threat to the advancement of his family.

Gildo soon found himself an ally in Minervius the Younger, urban prefect of Rome, and his uncle Minervius the Elder, the comes sacrarum largitionum. Minervius the Elder was one of the highest ranking bureaucrats in the West, in control of much of the imperial finances, including the salary of the imperial guard (an extension of his duties following the war for the west). He was originally to be intended to be an impartial middleman in charge of emperor Honorius’ safety. The Minervii were however not interested in being mere trustees of the four magistri militum. To further their own political ambitions, they made common cause with Gildo. A part of the funds meant for the Adriatic fleet were instead redirected by Minervius the Elder to increase the budget of the city of Rome’s grain supply. Both his nephew and Gildo profited from this move. Minervius the Younger profited in his role as urban prefect, as he was keen to win over the city’s population, something his father and predecessor had been unable to do, by means of bread and games. “The bread” was came mostly in the form of African grain. The state funds spent by the younger Minervius to be increasing amounts of grain went mostly into Gildo’s coffers, as he was the largest landowner in Africa.

Gildo did not only retain his exalted position in the political, military and economical hierarchy of the African provinces after his promotion to the office of magister peditum, but also used his new office to in the first hand enrich himself and strengthen his own powerbase. In fact he spent most of his time away from the court at Mediolanum instead focusing his attention on Africa. Small farmers were forced from their lands or had to enter servitude, rivals were murdered or went into exile and the division between civil and military administration was slowly eradicated. Gildo’s daughter Salvina would give birth to five children under her lifetime but only two would survive childhood: the fraternal twins Flaccilla Afra and Adeodatus [1]. He granted her large swaths of land to celebrate their birth in April of 400 and cement her position as his eventual successor.

Leo rightfully felt that Gildo neglected his duties as co-commander of the Italian army and only pursued personal goals to the detriment of the empire. He wrote lengthy letters lamenting about Gildo’s misconduct to Eutropius and expected the chamberlain to act against or at least curb the ambitious general. As he saw it Gildo and the Minervii went against the imperial will (i.e. Leo’s will) and decided over matters not in their jurisdiction, but he was mistaken to believe Eutropius would act against the Gildo. Eutropius instructed Leo to let the issue rest for the moment as he had his eyes set on the east and was not keen on causing infighting between the Western generals. Gildo was to valuable as an allie to lose over, what the chamberlain believed, were minor issues. Instead he and emperor Arcadius traveled to Syria in the spring of 400, as news had reached Constantinopolis that the Sassanians were faced with a serious revolt. A Persia descending into civil war would provide a golden opportunity to extend Rome’s power over the Persian vassal kingdoms of Armenia and Iberia. Eutropius instructed his generals to gather men for a potential campaign, hoping that the rightful shahanshah (“king of kings”) Vahram IV (Greek/Latin: “Varanes”) would loose control over the situation.

Vahram had recently survived an assassination attempt and his rule seemed precarious. The conspirators had considerable support and were able to force him to flee the capital, but counter to Eutropius’ hopes Vahram was able to quickly defeated his enemies and reasserted authority over his unruly Caucasian vassals in the late summer of the year 400, before even a single Roman unit had set foot in Armenia or Iberia. The Christian rulers of those vassal-kingdoms fell back in line as soon as they heard of the execution of Vahram’s enemies and the recapture of the capital. Eutropius and emperor Arcadius, who always remained in the shadow of his mighty chamberlain, stayed in Antiochia, cautious if the civil war really was over or if it would be reignited. And indeed a few months later, in the spring of 401 the situation worsened again: Iberia and Armenia were ravaged by Huns from north of the Caucasus while the Persian east fell into disarray.

Later Armenian chroniclers claimed that the Huns had been invited by Vahram to punish the Christian nobility for their disobedience, the truthfulness of this story has however been disputed, especially because the Huns also devastated Persian Assyria later the same year. In Persian chronicles the Hunnic raids are attributed to the machinations of the Romans. Eutropius surely appreciated the renewed conflict, as he had not yet given up hope that Rome could gain something in the process. Whatever the reason for the Huns’ incursion might have been, they caused great unease in the Persian empire. Vahram had already defeated Hunnic raiders a few years earlier, but this new incursion served to reignite the civil war. Some of the lords in the east had only grudgingly accepted Vahram’s victory over his enemies a few months prior and granted refuge to some of his adversaries. When the Huns crossed into the Persian Empire proper they rose in rebellion.

Italia in the meantime became all the more divided in the struggle for power between Gildo and Leo. Leo saw himself increasingly isolated and unable to pursue projects of his own; his orders were ignored or overridden by Gildo. The scale of Gildo’s and the Minervii’s obstruction seemed to have evaded Eutropius, as he did not act upon Leo’s multiple complaints. The chamberlain acted as an arbiter in some of the conflicts between the generals, but his verdict was usually not based on careful assessment of the situation and instead on rather shortsighted consideration. Eutropius usually assured Leo that his complaints would be addressed as soon as the Persian conflict was over. He decided mostly in Gildo’s favour as he did not want to lose a valuable ally inside the empire, while most of the East’s troops were stationed in Syria and Asia Minor, readying themselves for a potential Persian campaign. Leo’s problems seemed secondary when compared to the prospect of defeating the Sassanians. Issues like the underfunded Adriatic fleet did not bother the chamberlain. Without the backing of Eutropius Leo had only a few potential allies left; the most important were Bathanarius, the commander he had put in charge of the eastern Alpine passes, and Joannes [2], the recently appointed dux of Raetia. He had few friends inside the Italian military and even fewer at the Mediolanian court. It would be Leo’s attempt to make new allies, that would more than anything else contribute to his eventual downfall. In the autumn of 401, while Eutropius was busy in the east, Leo invited the deposed bishop Chromatius of Aquileia back to the West.

Chromatius had fallen from grace because of his anti-Gothic sentiment when Leo and Alaric invaded Italia and was forced to leave the West for the holy land. In his Palaestinian exile he had plenty of time, which he used to write letters to clerics and politicians alike. Most of his fellow bishops were in favour of him returning to the West, but his pleas to both the Western and the Eastern court had been unsuccessful for several years. While not caring too much about ecclestial matters Eutropius was reluctant to lift Chromatius’ ban. The chamberlain had pro-Gothic leanings, and was not keen on supporting an outspoken critic of the Goths’ branch of christianity. Some of the most important commanders at the Persian border were Goths as was the now quite distant yet still important Alaric. Eutropius relied on Gothic support and was well aware that it would be unwise to alienate them.

Some of Chromatius’ letters were addressed directly to Honorius, but his appeals usually ended up in the hands of Minervius the Elder, who had little reason to want the bishop back in Italia. Chromatius also wrote to other important political figures, including important military men, like Gildo, Leo and Jacobus; yet not to Alaric whom he still loathed. Gildo did not care for Chromatius, as many of his Berber supporters were Donatists and opposed to the Chromatius and his branch of Christianity. Alaric’s colleague Jacobus was famed for his piety but did not feel it was his duty to intervene on Chromatius’ behalf; firstly because he was not a man of the church but a military commander and felt it would be improper to intervene in ecclesiastical matters, secondly because Aquileia lay in Italia and therefore outside of his jurisdiction and thirdly because Chromatius’ downfall was caused by the bishop’s own arrogance and obstinacy, traits the general abhored. Leo initially refused to even consider the bishop's request, but during his year as consul he started to question if Eutropius would ever assist him in any greater capacity. The chamberlain’s eyes were firmly set on the eastern border and his interest for the West seemed minuscule. For the year 401 Eutropius arranged for Gildo’s son-in-law Nebridius to be appointed Western consul; as so often a half-hearted attempt to keep the African commander content. Leo decided it would only be in his own interest to find new allies, especially because emperor Honorius was nearing maturity, which meant that Eutropius would lose his legal role as guardian. The young Honorius showed no interest in actually ruling, which meant that either Eutropius would remain the power behind the throne - a increasingly unlikely prospect - or someone else would step in and rule on the emperor’s behalf. Leo already failed in his role as Eutropius’ stewart in the West, despite the chamberlains legal guardianship, and had little to no prospect of holding onto any kind of power over the emperor, when he would reach maturity. Only if he could find new powerful allies he could hope to remain in control.

The surprising death of bishop Venerius of Mediolanum in the summer of 401, was seen by Leo as an opportunity to make new friends in the West. Venerius had occupied the episcopal see of the Western capital for only a few months before succumbing to a pneumonia, which left his see vacant until a successor could be appointed. In an attempt to win the support of the mighty Trinitarian (also known as Orthodox or Catholic) church and its bishops Leo invited Chromatius to return to Italia, albeit not to his native city of Aquileia, which had already elected a new bishop, but to the imperial capital of Mediolanum. Allegedly it had been the dying Venerius himself, who had insisted that Chromatius should succeed him. Alaric’s personal poet Claudianus claimed that this was an outright lie created by Leo and Chromatius, but surviving letters by Venerius show that he had at least been supportive of Chromatius’ return to the West in general. The alleged dying wish of Venerius openly defied the established policy of the Western court; a policy backed by the Minervii and Gildo and in name also by Honorius. Leo was aware that this would cause upheaval at the court but was confident that the gains would outweigh the losses.

One of the late Venerius’ predecessors, the renowned Ambrosius, had once excluded emperor Theodosius from the eucharist following a massacre and only readmitted him several months later after the emperor asked for forgiveness. Ambrosius had at once demonstrated the considerable power of the Trinitarian church and successfully claimed the church’s spiritual supremacy over the emperor. Some authors have claimed that the last wish of Venerius was indeed real and that he wanted to go even further than Ambrosius. With his last breath Venerius wanted to assure that Honorius would relinquish imperial influence regarding the appointment of bishops and leave it fully to the church. It might have been that Leo lacked awareness of the implications his invitation carried for the relationship between the imperial office and the church, or that he simply did not care if the weak-willed Honorius’ successors would lose even more power, as he himself had no illusions of actually ever being emperor himself. Despite the reasons that could be brought forth against inviting Chromatius back to Italia, Leo did it anyway in the hopes of gaining the support of the church in general and of Chromatius, as bishop of Mediolanum, in particular. He rightly judged, that many bishops, among them the bishops of Rome and Constantinopolis, would be easily swayed in favour of his cause, but Gildo and the Minervii felt undermined and saw Leo’s invitation for what it was: an attempt to increase his own political capital. Joannes [3], bishop of Constantinopolis, publicly praised Leo for his decision and at the same time insulted both Alaric and Gildo, who he considered heretics. Alaric’s Goths mostly followed Arianism, while many of Gildo’s Berber kinsmen were Donatists. The African general was enraged.

Alaric did not want to upset the Gallo-Roman aristocracy, whose support he was eager to win, by actually doing something to stop the popular Chromatius from returning to the West. Sending a letter, drafted by Claudianus, condemning the bishop’s character was all he did for the time being. Italian court politics were also not his priority as he was leading a minor campaign in Britannia together with Jacobus. While the Gallic generals were busy in the north-western corner of the Roman world, the relationship between Leo and Gildo reached its breaking point. Gildo sailed to northern Italia accompanied - according to Claudianus - by a guard of over two-thousand men. He reached Mediolanum a few weeks later and was joined by his son-in-law the consul Nebridius. Leo realizing he had made a crucial mistake, had fled the capital before Gildo’s and Nebridius’ arrival. According to later legend he passed the arriving Chromatius on the way through the gates, but was in too much of a hurry to recognize his guest. A few days later Chromatius was forced into exile once more, before he had been formally consecrated as bishop of the city. Instead of the holy land, he was taken to northern Africa, where he spent the last years of life as a hermit in somewhere in the Numidian mountains.

Leo in the meantime went to the comes italiae Bathanarius, one of the few subordinates he deemed trustworthy. The dux immediately opened negotiations with Gildo to avoid a renewed civil war. While Bathanarius would not outright betray Leo, he made it abundantly clear that it was now him who was in charge. All of Leo’s communication would pass through Bathanarius and his guard was replaced by the dux’ men. Leo’ was little more than a prisoner in fine garb. Bathanarius, accompanied by a large share of his troops, met with Gildo outside Mediolanum. In late September of 401 they agreed on a new arrangement. Two different accounts exist in regard to Leo during this time: the first one claims, that he refused to leave his tent in Bathanarius’ camp out of pride; the second one claims he was not allowed to participate in the talks and turned to alcohol instead. Bathanarius extended his command as comes italiae and assumed control over most units north of the Apennines. Nebridius was appointed comes africae by his father-in-law, signaling that he and Salvina were to eventually succeed Gildo, whose advantaged age and adventurous life started to take a toll on him.

Eutropius was shocked to hear that Leo had fled Mediolanum and felt forced to finally intervene in the Western power struggle. During the first half of 401 Eutropius had successfully persuaded the king of Iberia to side with the Romans and had sent several legions to Iberia to assist him against the Hunnic raiders, which plagued the Caucasus region, and aid the small kingdom in an attack into neighbouring Armenia, which this time around had stayed loyal to Vahram, and later into Persia proper together with the Roman main army advancing from Syria. Eutropius had planned to attack the Sassanians in the autumn of 401, but began to doubt if it would be wise to wage war on Persia, while the West was slipping out of his hands. His decision to return west seemed to have been finalized when he got notified that Leo had been ousted from power by Bathanarius. Those who suffered most by this change of heart were the people of the Iberia. To their detriment the Roman troops under the Gothic general Tribigild did more harm than good

According to an anonymous Iberian historiographer most problems were due to Tribigild’s haste and greed, who had arrived in Armenia in the August of 401. When the Iberian king Trdat (Greek/Latin: “Tiridates”) refused to immediately march into Armenia and instead argued to wait for the Armenian nobility to rise in support of Rome, Tribigild allegedly warned him not to stretch his patience as he and his soldiers were desiring the spoils of war. According to the historiographer Trdat told the general that patience would reward him; to which Tribigild replied “No, Iberia will reward me”. The general subsequently left and marched back to the Empire but not without looting churches and burning villages on his way; taking everything of worth. The real reason behind Tribigild returning to the Empire was probably caused by Eutropius calling back all his troops, as he wanted to consolidate his grip on the West. The premature end of the Roman enterprise in the Caucasus could be read as an acknowledgement, that the chamberlain’s overarching strategy had failed, but Eutropius himself would have probably denied it instead pointing to that Persian rule in the area had been successfully destabilized.

Around the same time Tribigild returned to Roman Asia Minor, the Huns suffered a humiliating defeat against the Persians. Most of them turned northwards afterwards but some went to the west. Indeed small Hunnic contingents would reach the Romano-Persian border and extorted tribute from some villages a few weeks later. The only thing Eutropius’ impressive Syrian army achieved was to scare those raiders into returning to the steppes. The western provinces of the Persian Empire were pacified in the summer of 402 by Vahram, who to accomplish this task had to rely heavily on auxiliaries from Arabia and central Asia. Those auxiliaries also put down the eastern rebellion in the early months of 403 and marched into Iberia the same year. The regretful king Trdat was strangled on Vahram’s orders and the kingship abolished. Instead a Sassanian marzpan [governor of a border province] was appointed by the Persian court and ruled in Vahram’s name.

Most of the Eastern troops remained in Syria and nearby Asia Minor as bandits began to cause serious trouble in the southeast of the Anatolian peninsula: extracting protection money, robbing traders and plundering villages. Those Isaurian bandits raided an increasingly large area, which convinced Eutropius to take the land route through Asia Minor back to Constantinopolis, so he could personally supervise the beginning of the punitive expedition against the bandits. The imperial family in the meantime returned to Constantinopolis in November of 401. While still on his way to the capital Eutropius penned several letters in response to the de-facto ousting of Leo in late November. He had earlier ordered Gildo to retreat from the Western capital right after he was notified that Leo fled the city. Gildo answered that he that he had merely arrived with his personal guard and intended no harm. Eutropius was quick to respond that Leo was to retain his position but did not further demands, as he was not sure how things would develop and hoped for a peaceful solution to the generals’ conflict. He nevertheless prepared for a military interventions should Gildo chose to discard the chamberlain’s orders. A few weeks later it became apparent that Bathanarius and Gildo had reached an agreement to the detriment of both Leo, whose generalship had become a legal fiction, and Eutropius, whose orders were circumvented wherever possible. Eutropius subsequently penned several letters to Eastern and Western commanders alike. Similar to the Italian invasion of 398 the heavy burden of this military intervention was to be not on Eastern troops but on Germanic foederati. Eutropius envisioned a three-front-war: Godigisel’s Pannonian Vandals were to march into Italia from the north-east, where they were to be joined by Alaric’s Goths, who currently resided in Gallia. The East in the meantime was to prepare a naval invasion of Africa to crush Gildo’s rule once and for all.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

[1] Flaccilla Afra and Adeodatus

IOTL Nebridius died around 399 (we do not know what he died of but probably not high age). Salvina was called “young widow” by Hieronymus (aka St. Jerome) and had two young children. I have no exact figures regarding Salvina’s age but I would imagine that she still would be able to bear Nebridius children had he survived in OTL.

In TTL Nebridius does not die in 399 and instead he and Salvina have a pair of twins. As I would like to further explore the future lineage of Gildo but do not have any information regarding Salvina’s OTL-children I have decided that Flaccilla and Adeodatus would be a good way to let his family live on and be a meaningful part of TTL without having to invent names for OTL characters. Seeing that child mortality was quite high in antiquity I also judge it plausible that Salvina’s older children could die during childhood leaving the twins as Gildo’s only surviving grandchildren.

Regarding the names: Flaccilla Afra is named after Nebridius’ aunt the late empress Aelia Flaccilla (mother of Honorius and Arcadius). Afra is a nod to her place of birth and Berber ancestry. Adeodatus (lat. for “given by God”) stresses the family’s Christian faith and connection to the imperial dynasty as the name is similar in meaning to Theodosius (greek for “giving to God”).

[2] Joannes, dux raetiae

This is the same Joannes who had served Leo and Alaric during the War for Italia by among others negotiating the surrender of Aquileia. He has previously served at the Eastern court and his “promotion” to commander of the Raetian border troops might have been a way for Eutropius to get rid of ambitious courtiers. Despite having to trade Constantinopolis for the rather less glamorous Danubian border, he remained a supporter of Leo and voiced his disapproval when the general had to flee Mediolanum. Yet he did nothing to actually aid his superior in the conflict with Gildo, instead opting to wait for assistance from other parts of the empire.

[3] Joannes, bishop of Constantinopolis

IOTL he would be known as John Chrystotom (greek: chrisostomos = golden-mouthed) long after his death. ITTL he will be simply addressed as Joannes, just like all the other Joannes’ in the TL.

Modern OTL image of Mtskheta the capital of 5th century Iberia. © Wikimedia:User Doron, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike

For those who aspired to fame and glory the consulship was still a great achievement but the office had lost most of the political power, that has once been associated with it. It was was still extremely prestigious and a matter of public interest. Eutropius ascension to consulship in 399 had led to outrage, as many perceived a eunuch to be unworthy of this office. Had it not been for the resounding victory in the war for West, this could have caused his downfall. Eutropius was a man of increasing arrogance, who created enemies as he went, but he was also capable, cunning and ruthless - qualities that would help him hold on to the immense power he concentrated in his hands.

The consulship was in those years regularly awarded to imperial favourites, as a special honour, or simply occupied by the emperor himself to celebrate anniversaries or important events. The year 400 was no exception as the Western consulship was awarded to Leo, who had Eutropius to thank for it, and the Eastern consulship was occupied by emperor Arcadius, to celebrate the birth of his son Theodosius (called “the younger”) the year prior. Leo was no imbecile, even if Alaric’s favorite poet Claudianus likes to paint him this way, but he lacked the crucial qualities of that enabled Eutropius to rule as effective as he did. The chamberlain was well aware of that as he did never intend for Leo to be his equal. As his subordinate Leo was to act independently but in accordance with Eutropius’ policies, a task he soon showed to be incapable; not because he lacked the will but the cunning.

The seeds of Leo’s troubled career in the West were laid immediately after the end of the war for Italia. Soon after he was appointed magister for the Italian prefecture in the summer of 398, he had pushed for a quick reconstruction of the Adriatic navy which had suffered heavily in the last war. Leo’s initiative had been approved by Eutropius, but the chamberlain was unwilling to commit Eastern funds to the Adriatic navy, which he regarded as a secondary issue as best, leaving the matter of finance to the Western court. Without financial backing from the Eastern court and with a Western administration in disarray Leo had to postpone his plans for the navy and focused instead on the Italian peninsula’s Alpine defense. The office of comes italiae was established on his initiative and with the approval of Eutropius and Leo’s colleague Gildo. The dux was to survey and improve the fortifications of the eastern Alpine passes, which had fallen all too easily in the last war. Gildo put forward his own son-in-law, Nebridius the husband of Salvina, for the position, which was vetoed by Leo and subsequently denied by Eutropius, who as emperor Honorius’ regent had the last say in the appointment of military officials. Instead Bathanarius, a close acquaintance of the late Stilicho and popular with the army, received the office. Stilicho was held in high esteem by the Western soldiery, especially because his immediate successors had let the West in a profound crisis, that many believed Stilicho would have avoided. By installing Bathanarius, who had kept a low profile during the war, Leo wanted to improve his standing with the army of Italia. The choice of Bathanarius was welcomed by many common soldiers but Leo had still difficulties winning their affection and support. His poor performance on the battlefield, his extravagancy and his plump appearance made him the target of mockery and ridicule. Despite his honest attempts to improve the state of the Italian military, he was perceived as incompetent, selfish and out of touch with the soldiery. His poor diplomatic skills did not help either and would contribute to his eventual downfall.

Bathanarius in the meantime proved to be a good choice as he immediately set out to survey the Alpine passes, a enterprise that went on for the remainder of 398 and 399 before being concluded in the first weeks of 400 - the year of Leo’s consulship. The recently appointed consul set his eyes towards the reconstruction of the Adriatic navy but the year began with a disappointment: Eutropius showed himself once again unwilling to commit Eastern funds to the Adriatic navy and merely gave Leo the permission to use Western funds as he saw fit. Western resources were limited, especially because the important Illyrian provinces had been transferred to the East after the war, which had further diminished Western tax revenue. Amidst such monetary problems many at the court viewed the reconstruction of the Adriatic navy as an unnecessary pet project and were opposed to it. But as Leo had received Eutropius’ permission, which meant imperial permission, to use funds as he saw fit, he believed it to be superfluous to listen to courtly objections. The consul might have been successful with that tactic would it have not been for his colleague Gildo, who denied him support and even actively obstructed his plans. Gildo, who treated the African fleet like his personal property, had no interest in the resurrection of an potential adversary. Additionally the African commander disliked Leo on a personal level. Ever since his son-in-law Nebridius was denied the comitatus italiae in favour of Bathanarius Gildo would oppose Leo wherever possible as he saw him as a threat to the advancement of his family.

Gildo soon found himself an ally in Minervius the Younger, urban prefect of Rome, and his uncle Minervius the Elder, the comes sacrarum largitionum. Minervius the Elder was one of the highest ranking bureaucrats in the West, in control of much of the imperial finances, including the salary of the imperial guard (an extension of his duties following the war for the west). He was originally to be intended to be an impartial middleman in charge of emperor Honorius’ safety. The Minervii were however not interested in being mere trustees of the four magistri militum. To further their own political ambitions, they made common cause with Gildo. A part of the funds meant for the Adriatic fleet were instead redirected by Minervius the Elder to increase the budget of the city of Rome’s grain supply. Both his nephew and Gildo profited from this move. Minervius the Younger profited in his role as urban prefect, as he was keen to win over the city’s population, something his father and predecessor had been unable to do, by means of bread and games. “The bread” was came mostly in the form of African grain. The state funds spent by the younger Minervius to be increasing amounts of grain went mostly into Gildo’s coffers, as he was the largest landowner in Africa.

Gildo did not only retain his exalted position in the political, military and economical hierarchy of the African provinces after his promotion to the office of magister peditum, but also used his new office to in the first hand enrich himself and strengthen his own powerbase. In fact he spent most of his time away from the court at Mediolanum instead focusing his attention on Africa. Small farmers were forced from their lands or had to enter servitude, rivals were murdered or went into exile and the division between civil and military administration was slowly eradicated. Gildo’s daughter Salvina would give birth to five children under her lifetime but only two would survive childhood: the fraternal twins Flaccilla Afra and Adeodatus [1]. He granted her large swaths of land to celebrate their birth in April of 400 and cement her position as his eventual successor.

Leo rightfully felt that Gildo neglected his duties as co-commander of the Italian army and only pursued personal goals to the detriment of the empire. He wrote lengthy letters lamenting about Gildo’s misconduct to Eutropius and expected the chamberlain to act against or at least curb the ambitious general. As he saw it Gildo and the Minervii went against the imperial will (i.e. Leo’s will) and decided over matters not in their jurisdiction, but he was mistaken to believe Eutropius would act against the Gildo. Eutropius instructed Leo to let the issue rest for the moment as he had his eyes set on the east and was not keen on causing infighting between the Western generals. Gildo was to valuable as an allie to lose over, what the chamberlain believed, were minor issues. Instead he and emperor Arcadius traveled to Syria in the spring of 400, as news had reached Constantinopolis that the Sassanians were faced with a serious revolt. A Persia descending into civil war would provide a golden opportunity to extend Rome’s power over the Persian vassal kingdoms of Armenia and Iberia. Eutropius instructed his generals to gather men for a potential campaign, hoping that the rightful shahanshah (“king of kings”) Vahram IV (Greek/Latin: “Varanes”) would loose control over the situation.

Vahram had recently survived an assassination attempt and his rule seemed precarious. The conspirators had considerable support and were able to force him to flee the capital, but counter to Eutropius’ hopes Vahram was able to quickly defeated his enemies and reasserted authority over his unruly Caucasian vassals in the late summer of the year 400, before even a single Roman unit had set foot in Armenia or Iberia. The Christian rulers of those vassal-kingdoms fell back in line as soon as they heard of the execution of Vahram’s enemies and the recapture of the capital. Eutropius and emperor Arcadius, who always remained in the shadow of his mighty chamberlain, stayed in Antiochia, cautious if the civil war really was over or if it would be reignited. And indeed a few months later, in the spring of 401 the situation worsened again: Iberia and Armenia were ravaged by Huns from north of the Caucasus while the Persian east fell into disarray.

Later Armenian chroniclers claimed that the Huns had been invited by Vahram to punish the Christian nobility for their disobedience, the truthfulness of this story has however been disputed, especially because the Huns also devastated Persian Assyria later the same year. In Persian chronicles the Hunnic raids are attributed to the machinations of the Romans. Eutropius surely appreciated the renewed conflict, as he had not yet given up hope that Rome could gain something in the process. Whatever the reason for the Huns’ incursion might have been, they caused great unease in the Persian empire. Vahram had already defeated Hunnic raiders a few years earlier, but this new incursion served to reignite the civil war. Some of the lords in the east had only grudgingly accepted Vahram’s victory over his enemies a few months prior and granted refuge to some of his adversaries. When the Huns crossed into the Persian Empire proper they rose in rebellion.

Italia in the meantime became all the more divided in the struggle for power between Gildo and Leo. Leo saw himself increasingly isolated and unable to pursue projects of his own; his orders were ignored or overridden by Gildo. The scale of Gildo’s and the Minervii’s obstruction seemed to have evaded Eutropius, as he did not act upon Leo’s multiple complaints. The chamberlain acted as an arbiter in some of the conflicts between the generals, but his verdict was usually not based on careful assessment of the situation and instead on rather shortsighted consideration. Eutropius usually assured Leo that his complaints would be addressed as soon as the Persian conflict was over. He decided mostly in Gildo’s favour as he did not want to lose a valuable ally inside the empire, while most of the East’s troops were stationed in Syria and Asia Minor, readying themselves for a potential Persian campaign. Leo’s problems seemed secondary when compared to the prospect of defeating the Sassanians. Issues like the underfunded Adriatic fleet did not bother the chamberlain. Without the backing of Eutropius Leo had only a few potential allies left; the most important were Bathanarius, the commander he had put in charge of the eastern Alpine passes, and Joannes [2], the recently appointed dux of Raetia. He had few friends inside the Italian military and even fewer at the Mediolanian court. It would be Leo’s attempt to make new allies, that would more than anything else contribute to his eventual downfall. In the autumn of 401, while Eutropius was busy in the east, Leo invited the deposed bishop Chromatius of Aquileia back to the West.

Chromatius had fallen from grace because of his anti-Gothic sentiment when Leo and Alaric invaded Italia and was forced to leave the West for the holy land. In his Palaestinian exile he had plenty of time, which he used to write letters to clerics and politicians alike. Most of his fellow bishops were in favour of him returning to the West, but his pleas to both the Western and the Eastern court had been unsuccessful for several years. While not caring too much about ecclestial matters Eutropius was reluctant to lift Chromatius’ ban. The chamberlain had pro-Gothic leanings, and was not keen on supporting an outspoken critic of the Goths’ branch of christianity. Some of the most important commanders at the Persian border were Goths as was the now quite distant yet still important Alaric. Eutropius relied on Gothic support and was well aware that it would be unwise to alienate them.

Some of Chromatius’ letters were addressed directly to Honorius, but his appeals usually ended up in the hands of Minervius the Elder, who had little reason to want the bishop back in Italia. Chromatius also wrote to other important political figures, including important military men, like Gildo, Leo and Jacobus; yet not to Alaric whom he still loathed. Gildo did not care for Chromatius, as many of his Berber supporters were Donatists and opposed to the Chromatius and his branch of Christianity. Alaric’s colleague Jacobus was famed for his piety but did not feel it was his duty to intervene on Chromatius’ behalf; firstly because he was not a man of the church but a military commander and felt it would be improper to intervene in ecclesiastical matters, secondly because Aquileia lay in Italia and therefore outside of his jurisdiction and thirdly because Chromatius’ downfall was caused by the bishop’s own arrogance and obstinacy, traits the general abhored. Leo initially refused to even consider the bishop's request, but during his year as consul he started to question if Eutropius would ever assist him in any greater capacity. The chamberlain’s eyes were firmly set on the eastern border and his interest for the West seemed minuscule. For the year 401 Eutropius arranged for Gildo’s son-in-law Nebridius to be appointed Western consul; as so often a half-hearted attempt to keep the African commander content. Leo decided it would only be in his own interest to find new allies, especially because emperor Honorius was nearing maturity, which meant that Eutropius would lose his legal role as guardian. The young Honorius showed no interest in actually ruling, which meant that either Eutropius would remain the power behind the throne - a increasingly unlikely prospect - or someone else would step in and rule on the emperor’s behalf. Leo already failed in his role as Eutropius’ stewart in the West, despite the chamberlains legal guardianship, and had little to no prospect of holding onto any kind of power over the emperor, when he would reach maturity. Only if he could find new powerful allies he could hope to remain in control.

The surprising death of bishop Venerius of Mediolanum in the summer of 401, was seen by Leo as an opportunity to make new friends in the West. Venerius had occupied the episcopal see of the Western capital for only a few months before succumbing to a pneumonia, which left his see vacant until a successor could be appointed. In an attempt to win the support of the mighty Trinitarian (also known as Orthodox or Catholic) church and its bishops Leo invited Chromatius to return to Italia, albeit not to his native city of Aquileia, which had already elected a new bishop, but to the imperial capital of Mediolanum. Allegedly it had been the dying Venerius himself, who had insisted that Chromatius should succeed him. Alaric’s personal poet Claudianus claimed that this was an outright lie created by Leo and Chromatius, but surviving letters by Venerius show that he had at least been supportive of Chromatius’ return to the West in general. The alleged dying wish of Venerius openly defied the established policy of the Western court; a policy backed by the Minervii and Gildo and in name also by Honorius. Leo was aware that this would cause upheaval at the court but was confident that the gains would outweigh the losses.

One of the late Venerius’ predecessors, the renowned Ambrosius, had once excluded emperor Theodosius from the eucharist following a massacre and only readmitted him several months later after the emperor asked for forgiveness. Ambrosius had at once demonstrated the considerable power of the Trinitarian church and successfully claimed the church’s spiritual supremacy over the emperor. Some authors have claimed that the last wish of Venerius was indeed real and that he wanted to go even further than Ambrosius. With his last breath Venerius wanted to assure that Honorius would relinquish imperial influence regarding the appointment of bishops and leave it fully to the church. It might have been that Leo lacked awareness of the implications his invitation carried for the relationship between the imperial office and the church, or that he simply did not care if the weak-willed Honorius’ successors would lose even more power, as he himself had no illusions of actually ever being emperor himself. Despite the reasons that could be brought forth against inviting Chromatius back to Italia, Leo did it anyway in the hopes of gaining the support of the church in general and of Chromatius, as bishop of Mediolanum, in particular. He rightly judged, that many bishops, among them the bishops of Rome and Constantinopolis, would be easily swayed in favour of his cause, but Gildo and the Minervii felt undermined and saw Leo’s invitation for what it was: an attempt to increase his own political capital. Joannes [3], bishop of Constantinopolis, publicly praised Leo for his decision and at the same time insulted both Alaric and Gildo, who he considered heretics. Alaric’s Goths mostly followed Arianism, while many of Gildo’s Berber kinsmen were Donatists. The African general was enraged.

Alaric did not want to upset the Gallo-Roman aristocracy, whose support he was eager to win, by actually doing something to stop the popular Chromatius from returning to the West. Sending a letter, drafted by Claudianus, condemning the bishop’s character was all he did for the time being. Italian court politics were also not his priority as he was leading a minor campaign in Britannia together with Jacobus. While the Gallic generals were busy in the north-western corner of the Roman world, the relationship between Leo and Gildo reached its breaking point. Gildo sailed to northern Italia accompanied - according to Claudianus - by a guard of over two-thousand men. He reached Mediolanum a few weeks later and was joined by his son-in-law the consul Nebridius. Leo realizing he had made a crucial mistake, had fled the capital before Gildo’s and Nebridius’ arrival. According to later legend he passed the arriving Chromatius on the way through the gates, but was in too much of a hurry to recognize his guest. A few days later Chromatius was forced into exile once more, before he had been formally consecrated as bishop of the city. Instead of the holy land, he was taken to northern Africa, where he spent the last years of life as a hermit in somewhere in the Numidian mountains.

Leo in the meantime went to the comes italiae Bathanarius, one of the few subordinates he deemed trustworthy. The dux immediately opened negotiations with Gildo to avoid a renewed civil war. While Bathanarius would not outright betray Leo, he made it abundantly clear that it was now him who was in charge. All of Leo’s communication would pass through Bathanarius and his guard was replaced by the dux’ men. Leo’ was little more than a prisoner in fine garb. Bathanarius, accompanied by a large share of his troops, met with Gildo outside Mediolanum. In late September of 401 they agreed on a new arrangement. Two different accounts exist in regard to Leo during this time: the first one claims, that he refused to leave his tent in Bathanarius’ camp out of pride; the second one claims he was not allowed to participate in the talks and turned to alcohol instead. Bathanarius extended his command as comes italiae and assumed control over most units north of the Apennines. Nebridius was appointed comes africae by his father-in-law, signaling that he and Salvina were to eventually succeed Gildo, whose advantaged age and adventurous life started to take a toll on him.

Eutropius was shocked to hear that Leo had fled Mediolanum and felt forced to finally intervene in the Western power struggle. During the first half of 401 Eutropius had successfully persuaded the king of Iberia to side with the Romans and had sent several legions to Iberia to assist him against the Hunnic raiders, which plagued the Caucasus region, and aid the small kingdom in an attack into neighbouring Armenia, which this time around had stayed loyal to Vahram, and later into Persia proper together with the Roman main army advancing from Syria. Eutropius had planned to attack the Sassanians in the autumn of 401, but began to doubt if it would be wise to wage war on Persia, while the West was slipping out of his hands. His decision to return west seemed to have been finalized when he got notified that Leo had been ousted from power by Bathanarius. Those who suffered most by this change of heart were the people of the Iberia. To their detriment the Roman troops under the Gothic general Tribigild did more harm than good

According to an anonymous Iberian historiographer most problems were due to Tribigild’s haste and greed, who had arrived in Armenia in the August of 401. When the Iberian king Trdat (Greek/Latin: “Tiridates”) refused to immediately march into Armenia and instead argued to wait for the Armenian nobility to rise in support of Rome, Tribigild allegedly warned him not to stretch his patience as he and his soldiers were desiring the spoils of war. According to the historiographer Trdat told the general that patience would reward him; to which Tribigild replied “No, Iberia will reward me”. The general subsequently left and marched back to the Empire but not without looting churches and burning villages on his way; taking everything of worth. The real reason behind Tribigild returning to the Empire was probably caused by Eutropius calling back all his troops, as he wanted to consolidate his grip on the West. The premature end of the Roman enterprise in the Caucasus could be read as an acknowledgement, that the chamberlain’s overarching strategy had failed, but Eutropius himself would have probably denied it instead pointing to that Persian rule in the area had been successfully destabilized.

Around the same time Tribigild returned to Roman Asia Minor, the Huns suffered a humiliating defeat against the Persians. Most of them turned northwards afterwards but some went to the west. Indeed small Hunnic contingents would reach the Romano-Persian border and extorted tribute from some villages a few weeks later. The only thing Eutropius’ impressive Syrian army achieved was to scare those raiders into returning to the steppes. The western provinces of the Persian Empire were pacified in the summer of 402 by Vahram, who to accomplish this task had to rely heavily on auxiliaries from Arabia and central Asia. Those auxiliaries also put down the eastern rebellion in the early months of 403 and marched into Iberia the same year. The regretful king Trdat was strangled on Vahram’s orders and the kingship abolished. Instead a Sassanian marzpan [governor of a border province] was appointed by the Persian court and ruled in Vahram’s name.

Most of the Eastern troops remained in Syria and nearby Asia Minor as bandits began to cause serious trouble in the southeast of the Anatolian peninsula: extracting protection money, robbing traders and plundering villages. Those Isaurian bandits raided an increasingly large area, which convinced Eutropius to take the land route through Asia Minor back to Constantinopolis, so he could personally supervise the beginning of the punitive expedition against the bandits. The imperial family in the meantime returned to Constantinopolis in November of 401. While still on his way to the capital Eutropius penned several letters in response to the de-facto ousting of Leo in late November. He had earlier ordered Gildo to retreat from the Western capital right after he was notified that Leo fled the city. Gildo answered that he that he had merely arrived with his personal guard and intended no harm. Eutropius was quick to respond that Leo was to retain his position but did not further demands, as he was not sure how things would develop and hoped for a peaceful solution to the generals’ conflict. He nevertheless prepared for a military interventions should Gildo chose to discard the chamberlain’s orders. A few weeks later it became apparent that Bathanarius and Gildo had reached an agreement to the detriment of both Leo, whose generalship had become a legal fiction, and Eutropius, whose orders were circumvented wherever possible. Eutropius subsequently penned several letters to Eastern and Western commanders alike. Similar to the Italian invasion of 398 the heavy burden of this military intervention was to be not on Eastern troops but on Germanic foederati. Eutropius envisioned a three-front-war: Godigisel’s Pannonian Vandals were to march into Italia from the north-east, where they were to be joined by Alaric’s Goths, who currently resided in Gallia. The East in the meantime was to prepare a naval invasion of Africa to crush Gildo’s rule once and for all.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

[1] Flaccilla Afra and Adeodatus

IOTL Nebridius died around 399 (we do not know what he died of but probably not high age). Salvina was called “young widow” by Hieronymus (aka St. Jerome) and had two young children. I have no exact figures regarding Salvina’s age but I would imagine that she still would be able to bear Nebridius children had he survived in OTL.

In TTL Nebridius does not die in 399 and instead he and Salvina have a pair of twins. As I would like to further explore the future lineage of Gildo but do not have any information regarding Salvina’s OTL-children I have decided that Flaccilla and Adeodatus would be a good way to let his family live on and be a meaningful part of TTL without having to invent names for OTL characters. Seeing that child mortality was quite high in antiquity I also judge it plausible that Salvina’s older children could die during childhood leaving the twins as Gildo’s only surviving grandchildren.

Regarding the names: Flaccilla Afra is named after Nebridius’ aunt the late empress Aelia Flaccilla (mother of Honorius and Arcadius). Afra is a nod to her place of birth and Berber ancestry. Adeodatus (lat. for “given by God”) stresses the family’s Christian faith and connection to the imperial dynasty as the name is similar in meaning to Theodosius (greek for “giving to God”).

[2] Joannes, dux raetiae

This is the same Joannes who had served Leo and Alaric during the War for Italia by among others negotiating the surrender of Aquileia. He has previously served at the Eastern court and his “promotion” to commander of the Raetian border troops might have been a way for Eutropius to get rid of ambitious courtiers. Despite having to trade Constantinopolis for the rather less glamorous Danubian border, he remained a supporter of Leo and voiced his disapproval when the general had to flee Mediolanum. Yet he did nothing to actually aid his superior in the conflict with Gildo, instead opting to wait for assistance from other parts of the empire.

[3] Joannes, bishop of Constantinopolis

IOTL he would be known as John Chrystotom (greek: chrisostomos = golden-mouthed) long after his death. ITTL he will be simply addressed as Joannes, just like all the other Joannes’ in the TL.

Last edited:

I know that atleast a couple of people are reading this TL. It would be really nice to get some feedback on how the TL is progressing, what you thought about the last updates and let me hear if you want to have an update regarding something you find particularly interesting.

Want some feedback, here it goes: The title of the TL makes no sense to me, probably about a migration to the Americas of the descendants of Alaric who somehow become "Roman" Emperors. Second, I'm loving it! I only wished Gildo's administration and wars in Africa had some more "spotlights", because I'm sure he warred against some Berbers and Numidians, maybe recruit some mercenaries amongst them too, but idk Africa in this period is not my speciality. Keep up the good work, you're an awesome writer!

Thank you very much that means a lot to me!

The timeline's title is a remnant from several years ago when I first started a map series about, as you guessed correctly, the Roman Empire migrating to the Americas. "Araldyana" does refer to the area around the St.Lawrence River and OTL New England. Because this TL is based on my old map series I wanted to keep the name.

Gildo is an intersting person. He was more or less berber royalty. His father was named Nubel and bore the title regulus. Gildo had also several brothers and atleast one sister.

His (older?) brother Firmus had revolted against the empire and was defeated by the comes Theodosius the Elder (father of the emperor of the same name and grandfather of Honorius and Arcadius). Gildo had sided with Theodosius against his brother and later became the mightiest man in Africa. To ensure Gildo's loyalty, he was forced to send his daughter Salvina (and only child we know of) to Constantinople. There she was married to Nebridius, the maternal cousin of Honorius and Arcadius. This made Gildo a part of the extended imperial family.

Gildo's power was based on his connections to (and origin from) the Berbers, who mostly adhared to the Donatist sect of Christianity. I do not know if he was a Donatist himself but he seemed to have tolerated them atleast.

IOTL Stilicho didn't surprisingly die and instead warred against Alaric in Greece before returning West (without having accomplished much) and subsequently invading Africa because Gildo was in revolt. In the end another brother of his would be his undoing: Masceldelus, whom we have met ITTL. His OTL-campaign was much more effective and Gildo was killed trying to flee Africa. Afterwards Masceldelus died under suspicious circumstances, ending several decades of dominance by the House of Nubel in northern Africa.

ITTL Gildo obviously has survived and is more powerful than ever atleast for the time being but he is also getting old. It will be interesting to further explore his role in the next updates.

The timeline's title is a remnant from several years ago when I first started a map series about, as you guessed correctly, the Roman Empire migrating to the Americas. "Araldyana" does refer to the area around the St.Lawrence River and OTL New England. Because this TL is based on my old map series I wanted to keep the name.

Gildo is an intersting person. He was more or less berber royalty. His father was named Nubel and bore the title regulus. Gildo had also several brothers and atleast one sister.

His (older?) brother Firmus had revolted against the empire and was defeated by the comes Theodosius the Elder (father of the emperor of the same name and grandfather of Honorius and Arcadius). Gildo had sided with Theodosius against his brother and later became the mightiest man in Africa. To ensure Gildo's loyalty, he was forced to send his daughter Salvina (and only child we know of) to Constantinople. There she was married to Nebridius, the maternal cousin of Honorius and Arcadius. This made Gildo a part of the extended imperial family.

Gildo's power was based on his connections to (and origin from) the Berbers, who mostly adhared to the Donatist sect of Christianity. I do not know if he was a Donatist himself but he seemed to have tolerated them atleast.

IOTL Stilicho didn't surprisingly die and instead warred against Alaric in Greece before returning West (without having accomplished much) and subsequently invading Africa because Gildo was in revolt. In the end another brother of his would be his undoing: Masceldelus, whom we have met ITTL. His OTL-campaign was much more effective and Gildo was killed trying to flee Africa. Afterwards Masceldelus died under suspicious circumstances, ending several decades of dominance by the House of Nubel in northern Africa.

ITTL Gildo obviously has survived and is more powerful than ever atleast for the time being but he is also getting old. It will be interesting to further explore his role in the next updates.

Great TL much better than the first.

In the Wikipedia article about Gildo (I have a cousin with this same name) says: " Incited by the political machinations of the eunuch Eutropius, Gildo seriously entertained the notion of joining the Eastern Roman Empire by pledging fidelity to Arcadius." It would be extremely beneficial for the ERE to control the provinces of Byzacena and Africa Proconsularis, besides the tax benefits it would provide a great political control of the WRE court. It would be better for Eutropius to have him as a subordinate and then discreetly murder him, I also find it rather stupid move to give up his hostage (Salvina).

In the Wikipedia article about Gildo (I have a cousin with this same name) says: " Incited by the political machinations of the eunuch Eutropius, Gildo seriously entertained the notion of joining the Eastern Roman Empire by pledging fidelity to Arcadius." It would be extremely beneficial for the ERE to control the provinces of Byzacena and Africa Proconsularis, besides the tax benefits it would provide a great political control of the WRE court. It would be better for Eutropius to have him as a subordinate and then discreetly murder him, I also find it rather stupid move to give up his hostage (Salvina).

I only saw your post right now! Sorry that you had to wait such a long time for an answer.Great TL much better than the first.

In the Wikipedia article about Gildo (I have a cousin with this same name) says: " Incited by the political machinations of the eunuch Eutropius, Gildo seriously entertained the notion of joining the Eastern Roman Empire by pledging fidelity to Arcadius." It would be extremely beneficial for the ERE to control the provinces of Byzacena and Africa Proconsularis, besides the tax benefits it would provide a great political control of the WRE court. It would be better for Eutropius to have him as a subordinate and then discreetly murder him, I also find it rather stupid move to give up his hostage (Salvina).

It seems to me that Gildo wanted to "join" the East on his own terms. He was the single most powerful landowner in Africa and the military power was by this point quasi-heridatary. After all these years Gildo's rule was firmly entrenched and he would not be a mere pushover to the homo novus Eutropius. He surely wanted something in return, it was afterall a pretty daring move to openly rebel against the West (IOTL it was his undoing). Allowing his adult daughter to return seems like a rather small price, especially because having her as a de-facto hostage for ever wouldn't be viable. Salvina was well-connected and an imperial in-law. She also supported the mighty bishop Joannes (John Chrysostom) who was an outspoken critic of the lavish lifestyle Eutropius represented, sending her to Gildo could actually be seen as a good idea by Eutropius, as it would remove some influential political players (Salvina and Nebridius) from the capital.

Discreetly murdering Gildo is also always an option but I think Gildo played the game of thrones long enough to not be assassinated all to easily.

II.IV. Delusion and Ambition

II.IV. Delusion and Ambition

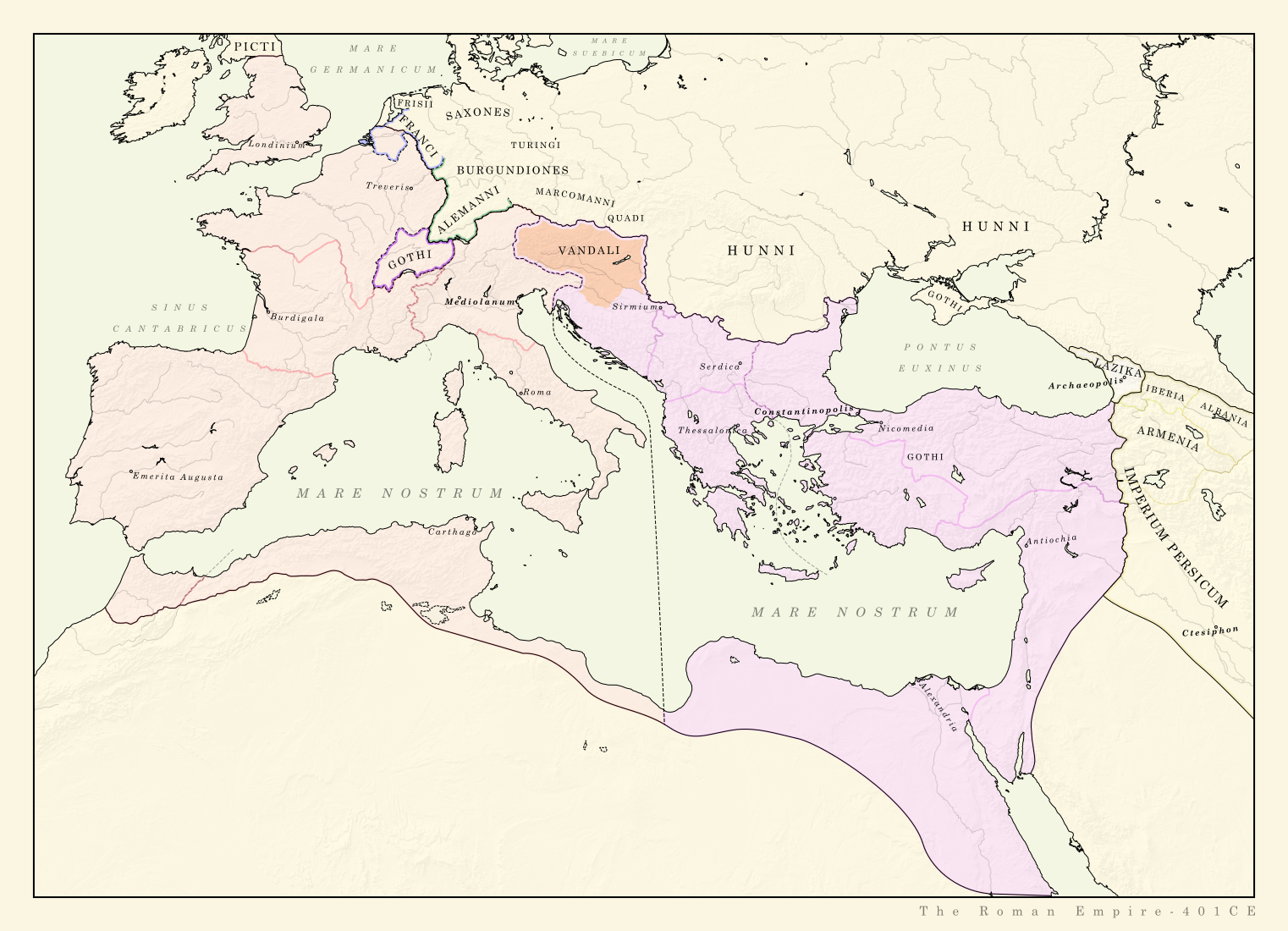

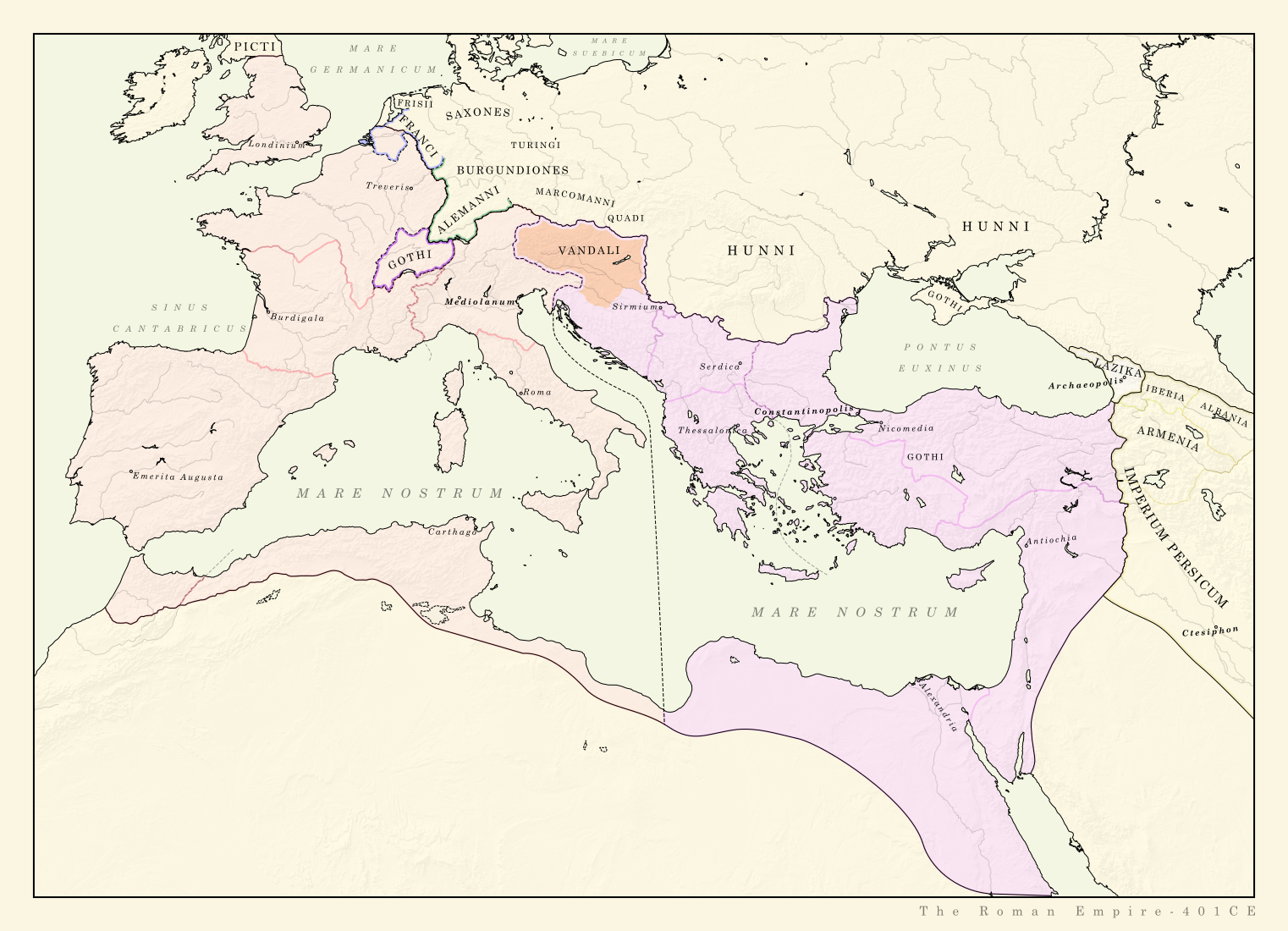

Eutropius’ Persian enterprise was considered a complete failure by many, but not by the chamberlain himself, who when he returned to the capital in February of 402 celebrated his “victories” against the Huns and Isaurians with lavish circus games. In earlier years he might have been more cautious and more aware of the political fallout of his actions, but his cunning had slowly been replaced by blind arrogance. For a few short years Eutropius felt almost untouchable: he had made himself de-facto regent of the East, he had been the first eunuch to occupy the consulship, he had pacified the warring Goths of Alaric and with their help dethroned arrogant Western generals who believed they could rule the East, he had defeated Hunnic raiders, he had persuaded the Iberians to side with Rome, and he had recently started to put an end to Isaurian banditry.

The chamberlain’s own view of his actions did not align well with how other courtiers and most commoners others perceived him. For them he was a quasi-usurper, who had undeserved power over the emperor and the court, who was a eunuch and former slave unworthy of the consulship, who send valuable troops west and made a barbaric warlord master over Gallia, who needlessly provoked the Persian king of kings, and who obviously preferred to practice the art of war against bandits over taking care of the empire’s real issues. The Danubian border was chronically understaffed, not at least because Alaric and his men were now guarding the the upper course of the Rhenus or campaigning in Britannia. Pannonia in the meanwhile was in a state of limbo as Godigisel and his Vandals had never gained a formal foedus from Eutropius. They had been allowed to settle in Roman Pannonia by Leo, who promised them annual grain rations and similar compensations in exchange for them guarding the Roman border and assisting him in case of war, but this arrangement faltered soon thereafter. Following the end of the war, mere months after Godigisel took control over the Pannonian provinces, Pannonia and the rest of the Illyrian prefecture were transferred from Western to Eastern jurisdiction, which meant that the Vandals now had to look towards Constantinopolis for payment. Godigisel had to wait in vain for formal recognition of his position by the East and had to realize that no annonaria would be forthcoming.

Godigisel had arguably done a fine job at keeping other tribes out of Pannonia but his Vandals had not been paid and instead took compensations in their own hands: small raiding parties attacked nearby villages and towns and some dared to venture as far south as Dalmatia. Those Vandal raiders were a nuisance to the provincials and to Godigisel who feared to lose control over his men. He sent letters to the Eastern court and to provincial magistrates pointing out that he and his Vandals deserved to be paid for their services as border guards. Whereas Eutropius did not sent any timely response some of the Pannonian magistrates affirmed Godigisel that his demands were just but that it was Constantinopolis responsible to pay him not theirs; they merely sent taxes to the capital and had no say in their distribution. The magistrates were rightfully blaming Eutropius for the Vandals problems and tried to stay on good terms with Godigisel but the rex seems to have read their response as an invite to cut out the unwilling middleman Eutropius.

In the spring of 400 Godigisel took control over the civil administration of the provinces he had already military control over, which included Pannonia Prima, Pannonia Valeria and Savia. The rex of the Vandals claimed that Eutropius had lost interest in the Danubian frontier and could not care less for the wellbeing of the Pannonians. His Vandals also marched into Noricum, which fell into their hands without bloodshed as its border fortifications were only manned by the bear minimum of soldiers, or in some cases completely deserted. During the war for Italia most of the Norican troops had followed their general’s command and marched southwards, only Jacobus, who organized the Roman defence further west had averted the total collapse of the Norican border by swiftly moving some of his troops there. After the war was won Jacobus was appointed magister militum in Gallia and Noricum was left to its own demise, as it was now officially under Eastern jurisdiction. Pannonia and Noricum had for a long time been a safety buffer for the Italian provinces: Germanic raiders had first to cross the Danubius and circumvent or defeat the Roman garrisons close by, before being able to even attempt a march across the fortified Alpine passes, but this buffer had mostly gone. Alemanni tribes raided Norican villages and towns with such a regularity that many settlements were deserted or moved to more defensible positions such as hilltops. Some Noricans allegedly traveled to Pannonia and urged Godigisel to restore order by driving the Alemanni back north. While this episode is certainly nothing more than thinly veiled Vandal propaganda, it shows that Godigisel was eager to not be perceived as the enemy of the Roman people.

By late summer of 400 all tax revenue from the Vandal occupied provinces seized to reach Constantinopolis. Eutropius, who at that time was still occupied with Persia, did demand that Godigisel send the outstanding taxes immediately or fear retaliation. The Vandal rex, now styling himself magister militum, did not act upon this, knowing full well that Eutropius could not muster the troops needed to defeat him while still campaigning in the East. He commanded without question the largest and most well-organized army along the course of the Danubius, all the way from the forests of the Alemanni to the Scythian delta.

The situation remained in a gridlock through most of 401. Eutropius was giving up on Persia but he was still unable to commit any troops to fight the Vandals, and Godigisel was cautious to not start an all out war. But the Vandals did not remain idle during their time in political limbo, instead the rex’ oldest son Gunderic lead some of his father’s best men southwards to the vicinity of Emona [OTL Ljubljana]. The city was an important transalpine outpost of the Western Empire. All armies that wanted to enter Italia from the East had first to pass Emona before they could try to overcome the alpine fortifications separating the peninsula from the lands to the East. To the relieve of the city’s population Gunderic did not try to sack Emona and instead went further west right to the very edge of the mountains to the fort of Nauportus. Leo had recently fled to Bathanarius and Gunderic was obviously interested in getting more information about state of affairs in the West, so he just went to Nauportus and asked the fort’s commander how things were going. He quickly realised that the Vandals had little to gain in the moment as Leo, who they had once sworn to assist in case of war was now a mere captive. The forts along the eastern alpine passes were also better manned and seemed to have better morale compared to only a few years ago when Alaric simply marched from Emona to Aquiliae without any resistance.