Thalassocracy

Μηδίζω! THE WORLD OF ACHAEMENID HELLAS

CHAPTER 7: DRAYA or THALASSA

THE LANDS BEYOND AGNIMITRA’S WAKE BY ARHAGUPTA TALISSARA (194 BCE)

YAWANA: KHORINTA

CHAPTER 7: DRAYA or THALASSA

THE LANDS BEYOND AGNIMITRA’S WAKE BY ARHAGUPTA TALISSARA (194 BCE)

YAWANA: KHORINTA

At a distance of 1500 kroshah, seated on the Neck of Yona on the southern side, there lies the famed city of Khorinta, placed in an ideal location between Northern Yona and the lands of Lora. Khorinta is at the head of a pradesha of Yawana, to which it also gives its name, which in ancient times was the lands belonging to the kingdom of Khorinta, once ruled by King Shis. It is the second most important Yawana city after Theeba itself, with a population of two hundred thousand, and the main base of the western fleet of the Iweri Empire, and it has been such since the Manishiyan kings first brought Yawana under their protection. It is governed as a republic, though it is under the command of the Iweri raja, and it has a long history of kings famous across the Yawana lands. The city was originally named for the Korandaka flower that is found there. The inhabitants believe the city to be three thousand years old, and to have been founded by Surya as a place of truce, who is worshipped in Khorinta by the token of his horses, a device widely used on the coinage of this city and widely considered to be its symbol among the Yawani. There are large temples to Surya, Varuna, and Rati here, though that which is the house of Rati is the most famous among the Yawani. The temple to Surya sits upon the Rock of Khorinta, the great mount that lies at the heart of the city, and its through its grandeur and placement above the majority of the city that the exaltation and devotion to Surya is shown by the citizens here. The city is immensely wealthy, through the endowments and patronage of its temples but also through its commanding position controlling trade through the Neck of Yona and in the bays on either side. Indeed, the city has two ports on either side of the Neck, with the walls of Khorinta extending outwards to encompass the road to its western port in the same manner that Athina does with its own nearby harbours. In earlier times there were attempts by the kings of Khorinta to dig canals across the Neck, but this was not successful, and instead an enormous paved path is maintained which allows ships to be pushed by slaves overland from one side of the Neck to the other, allowing ships to bypass the entirety of the journey around Yona. There are two houses of bhikku in the city, though there were once four. These were created by the embassies of the invincible king Agnimitra, and the two which still exist are now supported by the Iweri raja. The Khorinti are also patrons of one of the great athletic festivals of the Yawana, and are in general among the most pious and well ordered among the Yawana, though somewhat given over to love of wealth and sensual pleasures. Khorinta was also the homeland of Bhoosmegar, son of Varuna, and founder of the great city of Bhoosan, and the homeland of Phella, guardian of the horses of Surya.

THE FIRST ITALIOTE LEAGUE: THE HISTORY OF ITALIA VOLUME III

TARAS

TARAS

From the very start, Taras was both one of the greatest aids and obstacles to the formation of a lasting Italiote League. Their high martial reputation had already been established by this time, and they were already rivals to Dikaia, Lokris, Veii and Roma for sheer size. The League, combining the foremost Italian poleis and many of their less illustrious peers, could never hope to be assured of its integrity and strength against all comers if Taras did not consent to join the enterprise, and indeed Taras outside of the League might well have proven a viable threat in its own right. But the desire to include Taras in the League was ultimately about far more than just military concerns; the League was a sincere attempt to bring together the Hellenes of Italia into common purpose and harmony, to put aside the vicious wars between the various poleis. The arm of friendship and brotherhood was extended to all, with no churlishness about including the lesser Italian poleis, and the inclusion of Taras was therefore natural to achieve these more altruistic aims. The Italian project, conceived in Dikaia but adopted across the region, was one with high ambition.

There were several stumbling blocks to the assent of Taras into the more lasting Italiote League. They had been absolutely prepared to combine with the other Italians against foreign threats, first against the Iapogs alongside the Dikaians and then against the entirety of Italia against Karkhedor, but the Italiote League was a different level of commitment entirely. Firstly, the tyrant of the city, Aristotimos, was not predisposed to entirely trust the demokrats in Dikaia, Rhegion, or elsewhere, to not attempt an overthrow of the Tarentine form of constitution, particularly in the kind of intimate relationship the League seemed to presuppose. Secondly, the very power and wealth of the polis made its rulers willful and resistant to the idea of joining others in common policy where it might otherwise be able to act entirely self sufficiently and with concern only for themselves. And thirdly, perhaps crucially, it was exclusively up to Aristotimos to assent to this proposal, rather than appealing to a ruling council, assembly, or demokratic body the Italiotes had to convince a single man with entirely sovereign status.

There were several stumbling blocks to the assent of Taras into the more lasting Italiote League. They had been absolutely prepared to combine with the other Italians against foreign threats, first against the Iapogs alongside the Dikaians and then against the entirety of Italia against Karkhedor, but the Italiote League was a different level of commitment entirely. Firstly, the tyrant of the city, Aristotimos, was not predisposed to entirely trust the demokrats in Dikaia, Rhegion, or elsewhere, to not attempt an overthrow of the Tarentine form of constitution, particularly in the kind of intimate relationship the League seemed to presuppose. Secondly, the very power and wealth of the polis made its rulers willful and resistant to the idea of joining others in common policy where it might otherwise be able to act entirely self sufficiently and with concern only for themselves. And thirdly, perhaps crucially, it was exclusively up to Aristotimos to assent to this proposal, rather than appealing to a ruling council, assembly, or demokratic body the Italiotes had to convince a single man with entirely sovereign status.

However, among the Tarantinotes as a whole the prospect of a general settlement with the other Italiotes, let alone an active alliance, was extremely compelling and widely popular. The general sentiment was that Italia was much given over to conflict and that a general peace would be a welcome respite, along with a general admiration of how successful the joint adventures of the past decade had been. Pride was an emotion keenly felt by most Tarantinotes, but in the Italiote League was an opportunity for Taras to become yet greater still, as they saw it. Accordingly, by his suspicion of the other Italiotes, Aristotimos in fact guaranteed the result he feared, that of a general demokratic revolution, or at least this is how it was presented by the sources out of Dikaia written in contemporary times.

In actuality the events seem to have been more deeply ambiguous, with the initial aim being the removal of Aristotimos from power, not that of introducing a specific kind of new constitutional model. There were in fact two figures directly aiming to replace Aristotimos as tyrant during the overthrow, Mnesagoras the hipparkhos and Akesandros of Phoibea, who had both assembled retinues and mercenaries and competed to gain influence over the rest of the citizens. Events soon overtook and overwhelmed any notion of establishing a new monarch. A general and genuine call among the ordinary inhabitants of the city for a demokratic constitution began soon after Aristotimos sent in his mercenaries to put down the revolution by force. Mnesagoras and Akesandros, as well equipped and ambitious as they were, were now powerless against the tide of raw anger in Taras, and begrudgingly accepted the inevitable that had been unleashed. This, then, resulted in the creation of the Tarantine demokratic constitution after the exile of Aristotimos and his family, though the ambitions of Mnesagoras and Akesandros were in no way quelled.

The events of the revolution had passed so quickly that by the time the news had reached most of the Italiotes the new demokratic constitution had already been declared. It was difficult for the allies to disapprove of this result which guaranteed Tarantine entry into the Italiote League, and which removed one of the last tyrannies of Italia. But it made the continuation of Syrakousai participation in the League an open question, and reignited tensions in the city between its monarchy and those who wished to establish a demokratic regime. It must be said that the matter of constitution in Syrakousai had never been resolved, only delayed by common consent in order to resist the Karkhedonians. This was simply an opportunity for the tensions to break out once more. Many, however, directly pointed to Taras as having inspired the demokrats of Syrakousai, and there is certainly some truth in this. Without Taras’ revolution who knows how the century might have progressed for Syrakousai otherwise.

In actuality the events seem to have been more deeply ambiguous, with the initial aim being the removal of Aristotimos from power, not that of introducing a specific kind of new constitutional model. There were in fact two figures directly aiming to replace Aristotimos as tyrant during the overthrow, Mnesagoras the hipparkhos and Akesandros of Phoibea, who had both assembled retinues and mercenaries and competed to gain influence over the rest of the citizens. Events soon overtook and overwhelmed any notion of establishing a new monarch. A general and genuine call among the ordinary inhabitants of the city for a demokratic constitution began soon after Aristotimos sent in his mercenaries to put down the revolution by force. Mnesagoras and Akesandros, as well equipped and ambitious as they were, were now powerless against the tide of raw anger in Taras, and begrudgingly accepted the inevitable that had been unleashed. This, then, resulted in the creation of the Tarantine demokratic constitution after the exile of Aristotimos and his family, though the ambitions of Mnesagoras and Akesandros were in no way quelled.

The events of the revolution had passed so quickly that by the time the news had reached most of the Italiotes the new demokratic constitution had already been declared. It was difficult for the allies to disapprove of this result which guaranteed Tarantine entry into the Italiote League, and which removed one of the last tyrannies of Italia. But it made the continuation of Syrakousai participation in the League an open question, and reignited tensions in the city between its monarchy and those who wished to establish a demokratic regime. It must be said that the matter of constitution in Syrakousai had never been resolved, only delayed by common consent in order to resist the Karkhedonians. This was simply an opportunity for the tensions to break out once more. Many, however, directly pointed to Taras as having inspired the demokrats of Syrakousai, and there is certainly some truth in this. Without Taras’ revolution who knows how the century might have progressed for Syrakousai otherwise.

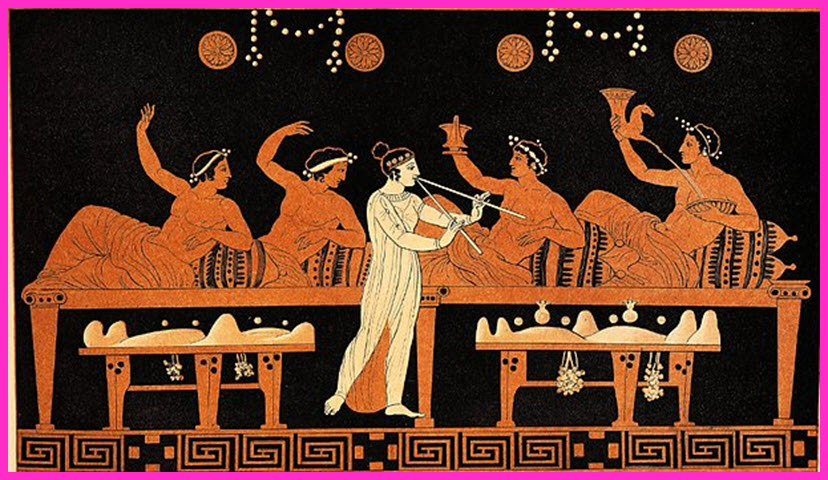

IN THE SERVICE OF APHRODITE BY KROKE (c.340 BCE)

THE GORGADES

It might be supposed that the hand of Aphrodite does not reach out to those stern warriors who are considered the most fierce and incorruptible, but the love between Ares and Aphrodite has ever been rich and fulfilling. Among their children are Harmonia, Eros, and Anteros, and they are the progenitors of all guardians of love. Though many common soldiers are the most base kind of lover, selfish and cruel and eager to gratify themselves, sometimes the very best lovers are those whose craft is war, and whose theatre is the battlefield. In fact, I would pronounce myself agreeable to the professional regiment rather than the practice of the temporary phalanx, for the quality of suitors that this produces. There are none that stand out in this manner more than the brothers of the Gorgades. Now, I am of course a Korinthian, as these fine men are in the service of my homeland it would be considered an obvious choice, but I am talking beyond my love of my motherland, deep and eternal as that love is. The Gorgades are as any body of men, their virtues are not all shared, their qualities not always equal. Nevertheless, among them are an above average number men of surpassing beauty, nobility, and wisdom, who any woman would be honoured in taking as a lover. Those who are frightened of their fearsome armour need not worry, for these men are eager to do away with their panoply, they are eager to cast aside their shell. They are often in want of tenderness and affection, all the more for their responsibility as the most feared marines of the Great Sea. Flattery will serve well but bawdiness will only serve to attract the lesser among them. Interest, affection, and above all patience will attract the finer among the Gorgades, and the rewards for all of this hard work will be more than worth it. Neither should you make a public fuss about your affection, as some men desire, for the Gorgades are already the focus of much attention, and have no need for such ostentatious displays of what they have won on the field of love.

BIBLIOTEKHE HISTORIKE BY MOHANE (29 CE)

ON YA

Ya, Kypros, the Copper Isle, is famed across the Great Sea for the quantity and quality of its copper above all, but also for its silver, its timber, and its wine. Its beaches are exceedingly pleasant, its ships proud and sturdy. It is a place of ancient piety, and has played host to many grand rulers and mighty Empires. It has never managed to manifest control over its own destiny, however, having been pulled between greater masters of loftier ambition and resources, ever since the foundation of Paphos by the Hellene Kinyras. The isle was first settled by those termed Eteokypriot by the Hellenes, who did not dwell in cities, then by the men of Phoinikia, and then by the Hellenes. This has left it with an unusual mixture of these various peoples, and was also the first occasion by which Hellenes became civilized by their contact with more developed Asian peoples. To the Hellenes this is the birthplace of Aphrodite, and the Temple of Aphrodite at Paphos is one of the most important sanctuaries of all the Hellenic regions. The island is also highly venerated by the Phoinikians, who lay claim to its foundation as the people from whom the line of Kinyras descended. As well as a centre of great piety the island is chiefly important for its naval utility for whichever great power is currently asserting control over the Great Sea, and for this reason the island has at times been a possession of the ancient empires of Assyria, Aigyptos, Parsa, Amavadata, and the Imerians. The island was divided between eight smaller kingdoms until the time of the Amavadatids, when this number was reduced to six, and it is currently now divided between three kingdoms, all of whom are loyal to the Imerian King. Merchants of Kypros are a frequent sight across the Great Sea, with a reputation of having a fine eye for glassware and metalwork. The source of many abandoned buildings of times past are Ya’s frequent, devastating tremors, held by the island’s people to be the movement of a giant serpent under the earth, or the work of the Hellenic god Poteidan. The Hellenes term this orogenia, a land where mountains are born, and this also causes them to hold the island as sacred. The snakes of this island are also held to be sacred, and frequently used by Phoinikians and Hellenes alike to invoke the healing powers of the Gods.

THALASSOKRATIA BY SITERHIRM OF TONATRIO (1671 CE)

THE ATHENIAN EXILES: THEIR SOCIETY

THE ATHENIAN EXILES: THEIR SOCIETY

We can never truly reckon the number of Athenians who left their city after the disaster at Salamis. Attempts to come to some total by assuming a minimum number necessary to found a city (Dikaia) are unsound, particularly when we know of contributions from other citizen bodies, and this yet remains the most sensible method used by scholars to solve this problem. What we can gleam is something of the makeup of this body of refugees from a few known facts. We know that men, women, and children departed, rather than soldiers and sailors alone. In some cases entire extended family units left, leaving entirely vacant lands with no familial heirs back home in Athens, most famously demonstrated in Against Porphanos where ownership of one of these abandoned plots had to be determined. We know that most of the Athenians who departed were not particularly rich nor considered socially influential, as the majority of the Athenian aristocracy remained behind, and also because such a large portion of the Athenian navy absconded. Let us not forget that, though they were free men, the citizen rowers of Athens were from the lowest classes of that society. We know that some of the resident foreigners in Athens departed alongside the citizens. Some clearly shared in the fears of their fellow residents as they departed before it was clear what would happen to Athens, others departed after it was clear that Dikaia was a firmly established enterprise that they might share in as equals.

This is the general shape of what would become the citizen body of Dikaia, although this was obviously augmented by the Sybaritai and the other contributors to the new foundation. This highly particular segment of the Athenian population was obviously not going to behave the same as the complete citizen body had previously, nor could its community simply become a second Athens. This was a reality that was not apparent at first. From the start aspects of Dikaian law, ritual life, and public behaviour sought to transplant key elements of Athens. There was a Dionysia, there were arkhontes, there were jury panels, there was even allegedly a perfect copy of the statue of Athena found in the Parthenon. The lettered men of this first generation, and many of their children, continued to talk in terms of Athenian classes and tribes. But the bedrock upon which this society was built was not the hoplite, or the clan patriarch, or the cavalryman. It was the oarsman. Without the desire of so many rowers to take exile rather than enter the service of the Persian King, could such a mass exodos ever have proven possible? These strong, trained men now also dominated the demographics of the polis. Their importance to the body as a whole, forming the first and really only viable line of defence against the Persians, was paramount. The question, as with any occasion where a specific demographic suddenly gains influence over the body as a whole, was whether the Dikaians as a whole would resist or accept this new state of affairs.

The answer, at first, was a qualified acceptance. The Dikaian navy, across the 5th century BCE, continued to expand, and this coincided with a growth in demokratic institutions and rights which cannot be considered unrelated. The quality and functionality of the Dikaian navy was vital, whether for combat against powerful foreign foes such as the Tinians and Karkhedonians, deterring incursions from Persia, or demonstrating Dikaian strength to the other Italiotes in the League of Kaulonia. Put simply, the Dikaians could not afford to alienate their rowers. Neither were the rowers passive in asserting their entitlement to greater status, pulling up their fellows in the lower classes alongside them. But this period, the era of the First Italiote League, is still one where the visual and literary icon of Dikaia and Italia in general is the hoplite, generally fighting some kind of Hesperian barbarian, at the very least in the defence of the Italiote world. The oarsmen were still in the background of the high culture of the citizen body they acted on behalf of. Their achievements were only celebrated on occasion, and even then much of the iconography of naval combat in that era focused on the marines, who notably sat entirely still on their ships unless they engaged in a boarding action.

It would be tempting to ascribe the collapse of Dikaia’s first hegemony, and the First Italiote League, to this half-hearted embrace of the oarsman and his vital service, but I must confess myself unconvinced by this line of thought. If one were to point to popular roots for the subjugation of Italia, then surely it must be with the increasingly proactive methods used by the Persian aristocracy to gain favour with their Hellenic subjects, the sheer size of the domains awarded to Taras over the course of multiple campaigns against the Iapyges, the economic strength of Syrakouse, and the lack of prestigious opportunities for the Keltoi in their own homelands. One cannot reasonably place the social position of the oarsman in Dikaia on an equal level to these truths, and indeed the Dikaian navy continued to act with skill and dignity through this period. But we can certainly point to the oarsman as bringing this low ebb for Dikaia to an end, nor the rowers of Dikaia alone.

With the collapse of Amavadatid control in Italia, generally dated to 296 BCE, there were many paths to take for Dikaia, and the Italiotes as a whole. On the one hand, revolt against the control of Syrakouse and Kapua was inevitable, as shown by the revolts in Dikaia, Rhegion, Laus, Sankle and Lokris that began in 294 BCE. But on the other hand, this did not necessarily mean a reestablishment of the Italiote League. Taras had for some time enjoyed a reasonably independent existence under the Amavadatid aigis and were now poised to become a powerful independent nation once again. The Dikaians might plausibly have hoped for something similar as they reunited their former territories. There are always temptations to forsake the more difficult path of co-operation for the more immediate gratification of hegemonia, and the Dikaians were no exception to that temptation. The moment of truth came when Syrakouse launched an expedition against Taras, who called for help from all of the former members of the Italiote League. Syrakouse seemed to have given up on recapturing Dikaia, and some accounts suggest that there had even been diplomatic negotiations between the two poleis. The Dikaians could plausibly have chosen not to interfere, and to instead expand their territory in Italia, perhaps even aligning themselves with Syrakouse. The oarsmen of Dikaia were having none of that.

The moment that news of the expedition became widely known, several Dikaian squadrons departed for Taras in order to aid their former allies, before the Boule had come to a decision or given any orders. The nauarkh who headed this ‘expedition’, Nausias, was firmly convinced of the need for unity against Syrakouse, and provided its leadership. But it was the universal belief in the rebirth of the Italiote League among his crews that enabled him to take this drastic decision. The Dikaians, having been presented with a fait accompli, ordered more ships to head to Taras, and were now committed. All they could do was wait.

The next fateful moment came when Nausias’ fleet arrived within sight of Taras, for there had been no time to send advance warning to the Tarantinotes that they were coming. The presence of a large Dikaian fleet, unannounced, was not automatically a cause for celebration, and the ships of Taras were ordered to prepare to defend the city. However, once it became clear that it was a Dikaian fleet that was approaching, the rowers of the Tarantine fleet began to cheer and celebrate, breaking up any move to intercept the new arrivals. Their faith was rewarded when the Dikaian squadrons came about and took up a defensive formation, leaving the Tarantine ships their old position on the left as had been normal in the fleets of the Italiote League. This gesture was universally understood among the Tarantinotes, and told them definitively that the Dikaians were once again taking up the cause of Italia.

The Dikaians, after all had been said and done, retroactively sanctioned all of Nausias’ actions, and could not avoid the fact that their sailors had jumped at the chance to reform the grand alliance between the Italiotes. These circumstances placed the oarsmen of Dikaia and Taras at the very heart of the Second Italiote League. Special naval coinage was issued to mark the occasion in all of the poleis party to the new League’s formation, and from this point onwards maritime imagery became a focal point of Dikian state iconography. Neither was this sentiment unique to Dikaia and its citizens; it is not coincidental that the bull-headed fish was used as a symbol of the Italiote League alongside the official federal symbol of the man-headed bull. The Italiote rebirth also marked more shifts in the structure of the Dikaian state, still recovering after its period of foreign domination (though it must be said that Syrakouse, as a fellow demokratic state, had not repressed any of Dikaia’s institutions, simply curtailing their independence and powers). The demokratic inclinations of the city became even stronger because the strength of the navy, and the lower classes it represented, was now unassailable. Members of the Ekklesia were compensated for attending its meetings, jury pay was increased, the class restrictions for becoming a member of the Boule were abolished (though candidates still had to be approved by their deme). This is the Dikaia that commentators in Hellas referred to derisively as an example of ‘radical’ demokratia, but Dikaia also captured the enthusiasm of its citizen body. Dikaia had begun as a bold enterprise, a new beginning for a body of exiled Athenians and those who chose to align with them. The polis had lost something of this lustre in its nearly two centuries of existence. The increased incentives to participate in its government changed the character of participation, and this would not have been possible without the influence of the oarsmen. The movers and shakers of that citizen body were now those who rowed their great warships, and those capable of speaking to their interests. This then is the birth of the naval demokratia of Dikaia.

This is the general shape of what would become the citizen body of Dikaia, although this was obviously augmented by the Sybaritai and the other contributors to the new foundation. This highly particular segment of the Athenian population was obviously not going to behave the same as the complete citizen body had previously, nor could its community simply become a second Athens. This was a reality that was not apparent at first. From the start aspects of Dikaian law, ritual life, and public behaviour sought to transplant key elements of Athens. There was a Dionysia, there were arkhontes, there were jury panels, there was even allegedly a perfect copy of the statue of Athena found in the Parthenon. The lettered men of this first generation, and many of their children, continued to talk in terms of Athenian classes and tribes. But the bedrock upon which this society was built was not the hoplite, or the clan patriarch, or the cavalryman. It was the oarsman. Without the desire of so many rowers to take exile rather than enter the service of the Persian King, could such a mass exodos ever have proven possible? These strong, trained men now also dominated the demographics of the polis. Their importance to the body as a whole, forming the first and really only viable line of defence against the Persians, was paramount. The question, as with any occasion where a specific demographic suddenly gains influence over the body as a whole, was whether the Dikaians as a whole would resist or accept this new state of affairs.

The answer, at first, was a qualified acceptance. The Dikaian navy, across the 5th century BCE, continued to expand, and this coincided with a growth in demokratic institutions and rights which cannot be considered unrelated. The quality and functionality of the Dikaian navy was vital, whether for combat against powerful foreign foes such as the Tinians and Karkhedonians, deterring incursions from Persia, or demonstrating Dikaian strength to the other Italiotes in the League of Kaulonia. Put simply, the Dikaians could not afford to alienate their rowers. Neither were the rowers passive in asserting their entitlement to greater status, pulling up their fellows in the lower classes alongside them. But this period, the era of the First Italiote League, is still one where the visual and literary icon of Dikaia and Italia in general is the hoplite, generally fighting some kind of Hesperian barbarian, at the very least in the defence of the Italiote world. The oarsmen were still in the background of the high culture of the citizen body they acted on behalf of. Their achievements were only celebrated on occasion, and even then much of the iconography of naval combat in that era focused on the marines, who notably sat entirely still on their ships unless they engaged in a boarding action.

It would be tempting to ascribe the collapse of Dikaia’s first hegemony, and the First Italiote League, to this half-hearted embrace of the oarsman and his vital service, but I must confess myself unconvinced by this line of thought. If one were to point to popular roots for the subjugation of Italia, then surely it must be with the increasingly proactive methods used by the Persian aristocracy to gain favour with their Hellenic subjects, the sheer size of the domains awarded to Taras over the course of multiple campaigns against the Iapyges, the economic strength of Syrakouse, and the lack of prestigious opportunities for the Keltoi in their own homelands. One cannot reasonably place the social position of the oarsman in Dikaia on an equal level to these truths, and indeed the Dikaian navy continued to act with skill and dignity through this period. But we can certainly point to the oarsman as bringing this low ebb for Dikaia to an end, nor the rowers of Dikaia alone.

With the collapse of Amavadatid control in Italia, generally dated to 296 BCE, there were many paths to take for Dikaia, and the Italiotes as a whole. On the one hand, revolt against the control of Syrakouse and Kapua was inevitable, as shown by the revolts in Dikaia, Rhegion, Laus, Sankle and Lokris that began in 294 BCE. But on the other hand, this did not necessarily mean a reestablishment of the Italiote League. Taras had for some time enjoyed a reasonably independent existence under the Amavadatid aigis and were now poised to become a powerful independent nation once again. The Dikaians might plausibly have hoped for something similar as they reunited their former territories. There are always temptations to forsake the more difficult path of co-operation for the more immediate gratification of hegemonia, and the Dikaians were no exception to that temptation. The moment of truth came when Syrakouse launched an expedition against Taras, who called for help from all of the former members of the Italiote League. Syrakouse seemed to have given up on recapturing Dikaia, and some accounts suggest that there had even been diplomatic negotiations between the two poleis. The Dikaians could plausibly have chosen not to interfere, and to instead expand their territory in Italia, perhaps even aligning themselves with Syrakouse. The oarsmen of Dikaia were having none of that.

The moment that news of the expedition became widely known, several Dikaian squadrons departed for Taras in order to aid their former allies, before the Boule had come to a decision or given any orders. The nauarkh who headed this ‘expedition’, Nausias, was firmly convinced of the need for unity against Syrakouse, and provided its leadership. But it was the universal belief in the rebirth of the Italiote League among his crews that enabled him to take this drastic decision. The Dikaians, having been presented with a fait accompli, ordered more ships to head to Taras, and were now committed. All they could do was wait.

The next fateful moment came when Nausias’ fleet arrived within sight of Taras, for there had been no time to send advance warning to the Tarantinotes that they were coming. The presence of a large Dikaian fleet, unannounced, was not automatically a cause for celebration, and the ships of Taras were ordered to prepare to defend the city. However, once it became clear that it was a Dikaian fleet that was approaching, the rowers of the Tarantine fleet began to cheer and celebrate, breaking up any move to intercept the new arrivals. Their faith was rewarded when the Dikaian squadrons came about and took up a defensive formation, leaving the Tarantine ships their old position on the left as had been normal in the fleets of the Italiote League. This gesture was universally understood among the Tarantinotes, and told them definitively that the Dikaians were once again taking up the cause of Italia.

The Dikaians, after all had been said and done, retroactively sanctioned all of Nausias’ actions, and could not avoid the fact that their sailors had jumped at the chance to reform the grand alliance between the Italiotes. These circumstances placed the oarsmen of Dikaia and Taras at the very heart of the Second Italiote League. Special naval coinage was issued to mark the occasion in all of the poleis party to the new League’s formation, and from this point onwards maritime imagery became a focal point of Dikian state iconography. Neither was this sentiment unique to Dikaia and its citizens; it is not coincidental that the bull-headed fish was used as a symbol of the Italiote League alongside the official federal symbol of the man-headed bull. The Italiote rebirth also marked more shifts in the structure of the Dikaian state, still recovering after its period of foreign domination (though it must be said that Syrakouse, as a fellow demokratic state, had not repressed any of Dikaia’s institutions, simply curtailing their independence and powers). The demokratic inclinations of the city became even stronger because the strength of the navy, and the lower classes it represented, was now unassailable. Members of the Ekklesia were compensated for attending its meetings, jury pay was increased, the class restrictions for becoming a member of the Boule were abolished (though candidates still had to be approved by their deme). This is the Dikaia that commentators in Hellas referred to derisively as an example of ‘radical’ demokratia, but Dikaia also captured the enthusiasm of its citizen body. Dikaia had begun as a bold enterprise, a new beginning for a body of exiled Athenians and those who chose to align with them. The polis had lost something of this lustre in its nearly two centuries of existence. The increased incentives to participate in its government changed the character of participation, and this would not have been possible without the influence of the oarsmen. The movers and shakers of that citizen body were now those who rowed their great warships, and those capable of speaking to their interests. This then is the birth of the naval demokratia of Dikaia.