The Great Western Salt Flats at the far end of Shindai's southern hemisphere constitute the heartland of one of the Kommersant's most storied warrior nations. Here, among the endless expanses of shallow brine pools and featureless salt pans, a proud and fierce people arose from the bloodied and battered survivors of the old Interstellar Commerce Authority's aerospace-interceptor corps. The cataclysmic orbital battle that saw the destruction of the great interstellar fleets was a contest that pitted cruiser against cruiser, frigate against frigate, and of course fighter against fighter. As they had in previous campaigns across countless star systems, the autonomous combat fighter-drone swarms of the Combined People's Liberation Fleet proved to be formidable opponents for the attack-interceptors of the ICA's aerospace superiority wings. But enough ICA pilots survived the destruction of the great fleets to haphazardly coordinate the emergency landings of three gutted attack wings and their heavily damaged carrier support elements among the Great Western Salt Flats, which afforded the best landing zones in the southern hemisphere for those small craft with enough in the way of fuel and operational systems to reach the desolate locale.

Here the survivors remained in isolation for a century among the ruins of the wrecked attack craft and interceptors that had brought them to the surface of this backwater world and which gave that stretch of the Western Salt Flats its colloquial name: the Boneyard. Far removed from the distant and primitive wars of desperate attrition fought between the reconstituted forces of the Kommersant's First Commodore and the Red shock brigades, the descendants of the Boneyard survivors were free to tinker with the battered wreckage of their forefathers' aerospace fighters. Although much technical knowledge and high technology had been irretrievably lost with the collapse of interstellar civilization, it was not long before the tribes of the Boneyard, ever cognizant of their ancestors' lofty aerospace origins and raised from childhood on tall tales of legendary interceptor-jockeys and subspace dogfights, inevitably redeveloped the basic principles of manned flight. They took to the skies in primitive gliders constructed of salvaged duralum and polymer sheet, shot into the air from catapult-operated launch ramps, and cruised high up on the gentle thermal vortexes of the arid salt flats. With the aid of their newfound aerial vantage point, it became ever easier to track and hunt the roving packs of rock lizards and migrating flocks of salt gulls that sustained their people. And it was not long, too, before they began converting these increasingly complex gliders into weapons of war.

Isolated though they were from the greater conflicts raging across both hemispheres of the planet at large, the people of the Boneyard were kept more than occupied by severe internal strife and dissension that often culminated in violent clashes. Arrayed and divided against one another by squadron rivalries and recriminations dating all the way back to the time of the Collapse, the descendants of the three attack wings fought two dozen tribal wars among the dry salt flats in the span of a century. Petty squabbles over contested hunting grounds and inequitable division of wreck salvage frequently provided the instigating impetus for aerial skirmishes and raids fought between the fiercely combative squadrons. Gliders armed with explosive rocket and revolver cannon clashed with one another in the cloudless skies of the Great Western Salt Flats, littering the land with fresh wrecks that were quickly cannibalized for spare parts, munitions, and materials. But despite the savage energy and enormous quantity of irreplaceable resources expended in these violent struggles, they were often relatively bloodless affairs. There was no loss of honor or prestige associated with ending an aerial contest by means of that universally recognized signal of surrender, the waggling by a pilot of his glider's wings. Had his valor and skill in the air been particularly praiseworthy, the surrendered pilot and sometimes even his glider, though stripped of weapons and squadron insignia of course, would be returned to his tribe to fight another day. And ultimately many a protracted war was brought to a swift resolution by single combat in the air between tribal champions, with the hosts of both warring squadrons observing the decisive duel from afar.

Thus a century was spent amidst the blood and fire of the tribal wars, driving deep divisions between the squadrons even as it molded their people into the finest aviators of their time. Even as the first exploratory gun-clipper detachment of the Kommersant's Mercantile Fleet Command beached its hulls on the northern rim of the Great Western Salt Flats and disgorged the blue-jacketed kosmodesantniki infantry pickets upon the briny shore, the pilots of the Boneyard were embroiled in yet another three-way tribal conflict between the warring squadrons, who temporarily suspended hostilities to meet the Kommersant emissaries under a flag of truce. Predictably, first contact between the two estranged peoples immediately took a turn for the worse when the Kommersant Trade Commissioner delivered the Standard Articles of Corporate Sovereignty to the high colonels of the warring squadrons. Like the Texacor nation on the other side of the hemisphere, the tribes of the Boneyard bridled at what effectively amounted to a Kommersant ultimatum for immediate and unconditional annexation, based on what they considered to be the obsolete corporate obligations of their long dead forefathers. To add insult to injury, the Kommersant Trade Commissioner announced that his fleet would return in one month's time to accept delivery of the signed Articles of Corporate Sovereignty, along with half a million Adjusted Dollars in trade tax and the first levy of conscripts for immediate service in the Kommersant's latest campaign against the ever rebellious Texacoran separatists halfway around the planet.

Practically overnight, the sudden arrival and departure of the Kommersant expeditionary force had managed to unite the tribes of the Boneyard to a hitherto unprecedented degree. Rallying under the banners of the Three Wings of old, the squadrons came together for the first time in living memory, united by a common love for their fiercely cherished tribal independence. An Ace of Aces was jointly chosen from the colonels of the squadrons to command all Three Wings in battle for the first time since the Collapse, and it was not long before the full fury of the Three Wings was unleashed upon the returning Kommersant expeditionary force. The fleet officers of the Kommersant gun-clippers and their bluejacket counterparts among the desantnik infantry detachments had all observed the aerobatic prowess of the tribal gliders from afar during a demonstration display presented by the tribes in honor of the Kommersant Trade Commissioner in the midst of the first tentative diplomatic negotiations, but they had all unanimously failed to anticipate the tactical ramifications of that maneuverability. Although the free flying gliders of the Three Wings squadrons bore a superficial resemblance to the observation kites and tethered air balloons of Djong-Kok and Red war fleets which Kommersant fleet gunners were accustomed to swatting from the sky with high elevation volleys of musketry and explosive shell, they were far from the static targets presented by the aerial observation platforms and signalling stations of the northern nations. Instead, the free-flying gliders of the Three Wings proved to be elusive prey for even the best drilled Kommersant gunnery crews and desantnik sharpshooters, while their aerial bombs and revolver cannon wrought havoc among the unarmored top decks of the Kommersant gun-clippers.

The equivalent of almost an entire Kommersant mobile squadron was sunk that day in the briny shallows to the north of the Great Western Salt Flats, with just the crippled flagship and a trio of damaged escorts escaping home to report the near total destruction of the expeditionary force. Preoccupied with the unsuccessful subjugation of the Texacoran separatists in the first War Between the Fleets, the Kommersant's First Commodore of the day ordered a blockade of the Great Western Salt Flats to contain the tribal insurrectionists of the Three Wings until sufficient forces could be assembled to mount a full-scale expeditionary effort against the insolent rebels. However, the Kommersant blockade did little to starve the Three Wings, as the united squadrons drew all the sustenance and material they required from the rich debris fields of the Boneyard. In fact the blockade stretched Kommersant fleet pickets in a thin arc across hundreds of kilometers of calm briny shallows, providing a multitude of predictable and relatively static targets for the war gliders of the Three Wings, much to the despair of those Kommersant provisional admirals and commands assigned to blockade duty. As Kommersant losses mounted and the fame of the Three Wings accordingly rose, the airborne tribals effectively became co-belligerents with the Texacoran nation in the first War Between the Fleets, despite the fact that they fought their battles on opposite ends of the hemisphere and were only aware of the other nation's existence through dispatches and propaganda captured from their common foe.

Thus, when that conflict was brought to an end by the so-called Admirals' Putsch, which saw the Chief Executive Commodore of the day deposed by the commanders of the Kommersant home fleets, the Texacoran Secretary of War successfully lobbied for the Kommersant junta to grant the Three Wings a place at the peace negotiations. So it was that the Ace of Aces, heading the diplomatic delegation of the Wingmen, came to meet the Texacoran Secretary of War and his general staff in the heart of the Kommersant capital, establishing a cordial if tenuous friendship between the two nations that would endure for almost a century despite their vast geographical separation. In the alternating decades of peace and conflict between the First and Third of the Wars Between the Fleets, the Texacor and the Three Wings would occasionally exchange military attaches and observation missions, with three consecutive generations of Wingmen colonels being educated at the Texacoran Tactical College. In times of war against the common Kommersant foe, the Texacoran amphibious brigades and the Wingmen battle squadrons synchronized the tempo of their operations at opposite ends of the globe in order to divide the attention and split the strength of the Kommersant's mobile squadrons.

But as the Texacor consolidated and even expanded their hold on their advantageously located archipelago environs through the decades, the unruly squadrons of the Three Wings gradually fell back into the old patterns of internal tribal rivalries when not united in wars against the hated Kommersant. Without the promise of the rich loot and salvage to be gained from raiding Kommersant shipping routes and commercial convoys, the free-spirited pilots of the Three Wings often felt little incentive to elevate one of their tribal rivals to the exalted title of Ace of Aces. Bereft of high level leadership in times of peace, the divided squadrons struggled to devise and execute a cohesive policy of foreign alliances and internal development despite reaping the technological benefits of the industrial revolution of the age. So even as the Wingmen traded their traditional light gliders for the first generation of high-speed steam turbined fighters and exchanged the old smoothbore revolver cannons for motor-actuated mechanical repeaters, they developed a growing dependence on foreign fuel and materials to sustain the modernization and upkeep of their battle squadrons. There was no question that modernization was essential to the survival of the Three Wings as an independent nation, as the Kommersant developed and deployed increasingly sophisticated anti-aircraft countermeasures and tactics with each new conflict between fleet and squadron. The introduction of incendiary canister shot and time-fuzed explosive shells aboard Kommersant gun-clippers crewed by gunnery officers with training in high elevation barrage drill more than matched the newest generation of turbine-powered fighters and aerial armaments employed by the modernized squadrons of the Three Wings.

By the time of the Second War Between the Fleets, the Wingmen had exhausted their ancestral Boneyard of all salvageable duralum and lightweight polymer despite relentless cannibalization and recycling of decommissioned and obsolete aircraft. To fill the vacuum, the Wingmen came to rely on peacetime imports of Kommersant duralum and ceramsteel to construct new airframes, while the mercantile Berger clans and Orbitaaler trading laagers of the nomadic Afrikander republics supplied the increasingly vast quantities of nanodust fuel required to keep the new turbine-powered fighters of the Three Wings in the air.

It was this dependence on Afrikander nanodust that would prove to be the Achilles' heel of the Three Wings. As the divided tribes vied to develop and field ever more advanced models of high performance fighters and cultivate a rather well deserved reputation for petty piracy over the southern seas, they came to take for granted the regular shipments of high-grade Afrikander nanodust from the hellish equatorial reaches, as the nomad republics of the Orbitaaler and Berger clans were always avowed neutrals in the military conflicts of the southern hemisphere, ensuring that Afrikander trade laagers and mercantile fleets enjoyed free access to the border ports of the Three Wings, even in times of war against the Kommersant. Thus, the Wingmen were rudely awakened by the outbreak of the Great Dust War, which saw the gun-clipper fleets of the Kommersant steam into battle against the Afrikander nomad republics of the equatorial latitudes. In a matter of months, the flow of Afrikander nanodust to the Wingmen of the Great Western Salt Flats had slowed to a trickle as the Afrikander republics recalled their trade laagers and mercantile squadrons to bolster the defense of their threatened equatorial territories. Although the Three Wings remained on a nominally peacetime footing, having just concluded the last in a series of non-aggression treaties with the Kommersant in order to buy enough time for a series of organizational and technological reforms in preparation for the next anticipated war, they gradually burned through their fuel stores of nanodust to the point of tapping into their emergency reserves. With the vast majority of their airframes demobilized and laid up in hangar for overhaul and modernization, the Wingmen could only watch and hope for a swift and decisive Afrikander victory in the Great Dust War.

As the war dragged on year after year, their hopes and spirits were dashed by the realization that the Kommersant would eventually gain the upper hand and likely secure nanodust trading concessions from the Afrikander republics, including the nanodust shipping routes that had hitherto replenished the fuel stores of the Three Wings. Their worst fears were realized when news arrived of the peace negotiations concluded between the Kommersant and the Afrikander republics in the last year of the war. The Afrikander clans had surrendered their southern nanodust trading routes to the Kommersant, giving the hated foe of the Wingmen a near total monopoly on the supply of nanodust to the lands of the Three Wings. Recognizing the dire nature of the situation they faced, with the very lifeblood of their nation passing exclusively through the hands of their ancestral enemy, the squadron colonels of the Wingmen elected an Ace of Aces from among their number to confer with the Texacoran Secretary of War to search for a possible solution to the crisis. An initial attempt was made at rerouting a portion of the southern Texacoran trade routes to the Great Western Salt Flats in order to provide at least a trickle of nanodust to the hungry squadrons of the Three Wings, but the Texacoran supply convoys soon found their newly plotted shipping lanes obstructed by Kommersant blockade patrols directly aimed at constricting the flow of precious nanodust to the Wingmen.

Nevertheless, the Kommersant's mobile squadrons and war fleets were worn and weary from years of bitter campaigning in the equatorial wastes against the hardy Afrikander republics, so both Wingmen and Texacor were optimistic about the chances of success for a military solution to the crisis. A series of lightning offensives into the corporate heartlands of the Kommersant was expected to bring the Chief Executive Commodore to the negotiating table before the Three Wings exhausted the last of their emergency nanodust fuel reserves. Thus the last and most recent War Between the Fleets was inaugurated, with all three nations scrambling to fight a war that none had genuinely expected nor adequately prepared for. Although the forces of the Kommersant had indeed suffered severely from their recently concluded operations in the Great Dust War, the fact that the battered mobile squadrons had not yet been demobilized and were largely crewed with campaign veterans rather than the usual green cadres of levy conscripts gave the Kommersant's provisional admirals an advantage that had not been underestimated by the strategists of Texacor and the Three Wings. Initial victories scored by the Wingmen and Texacor soon gave way to a succession of surprising defeats at the hands of Kommersant commanders and admirals whose ranks had been purged of those unable to survive the brutal conditions of equatorial campaigning against the wily Afrikander kommandants and vek-kapteins.

Although the last War Between the Fleets was to stretch on for two more years and result in an bloody stalemate between Texacor and Kommersant, the fuel-starved squadrons of the Three Wings were forced to capitulate to the despised Kommersant after decisive victory eluded their grasp within the first year. With their nanodust reserves totally exhausted and no prospect of timely resupply from the Texacoran amphibious divisions that were fighting for their very survival halfway around the planet, the Wingmen were powerless to act as the advance pickets of the Kommersant's 472nd Mobile Squadron steamed into the briny shallows north of the Great Western Salt Flats and landed khaki-clad kosmodesantniki battalions in full view of the grounded aircraft of a dozen proud Wingmen squadrons. Aboard the flagship of a mere provisional admiral of the Kommersant, the Ace of Aces and the high colonels of the Three Wings were forced to unconditionally sign the Articles of Corporate Sovereignty that their legendary forefathers had rejected a century ago. In one fell swoop, the Three Wings had lost their cherished independence, and with Kommersant annexation they feared the total ruin of their nation and the disbandment of their proud battle squadrons, whose prized airframes were already being shipped back to the Kommersant capital as war trophies.

But to the surprise of the Wingmen, they found that after the first few harsh years of Kommersant rule and armed occupation, their newly installed corporate overlords were willing to overlook their ancestral scorn for what they regarded as a savage tribe of airborne pirates in deference of military necessity. In the years following the bitter peace that settled the last War Between the Fleets, the gradual extension of Kommersant trade routes into the northern hemisphere and establishment of colonial footholds and corporate client states among the fragmented Djong Kok archipelagos and Red provinces had revealed a need for long range power projection that only the airpower of the Wingmen could hope to satisfy.

The gun-clippers of the Kommersant's mobile squadrons, fast and numerous though they were, found themselves stretched thin among the vast expanses of the northern hemisphere, where the Kommersant's colonial enterprises and intrigues often collapsed into regional conflicts and uprisings. The long range striking power offered by the mothballed fighter-bombers of the Three Wings presented an attractive means of augmenting the mobile response of the Kommersant's colonial garrisons and frontier policing fleets. Thus the Chief Executive Commodore of the Kommersant permitted the reactivation of several Wingmen squadrons on a limited basis for forward deployment to the northern hemisphere frontier with the Red Empire. The reformed battle squadrons of the Three Wings were outfitted with the last generation of high performance fighter-bombers, hastily recalled from the Kommersant military proving grounds at which they were being evaluated, and crewed by veteran Wingmen who had proven their skill in the last War Between the Fleets. Operating from flattop Kommersant clippers converted at frontier drydocks for take-off, landing, rearmament and refueling, the first flights of Wingmen took to the air since the great capitulation, though they flew through the blustery foreign skies of the northern hemisphere, in service of the Kommersant, and against the alien peoples of the Djong-Kok city states and the Red Empire.

Within a short period of time, the reactivated squadrons of the Three Wings had made their mark on Kommersant operations in the northern hemisphere. Long range Wingman reconnaissance patrols kept the Kommersant's provisional admirals well-appraised of the dispositions and deployment of hostile Red fleets and Djong-Kok pirate bands, while Wingman strafing raids harassed and broke up hostile formations long before they came within firing range of Kommersant gun-clippers. In the pitched battle of fleet-on-fleet general engagements, Wingman fighter-bombers cleared the skies of Djong-Kok signalling balloons and tethered Red gun-kites, before shifting their attention to isolated war junks, vulnerable to direct armor piercing bomb hits, and unarmored sailskimmers, which could easily be sunk by as little as one or two concentrated strafing runs. And in support of Kommersant desantnik infantry and colonial levies clinging to landing beachheads, the Wingmen flew close air support sorties, laying explosive cannon fire and incendiary dust bombs danger close among the ranks of counterattacking Red shock infantry. Although the handful of tenacious Wingmen rarely decided alone the outcome of every hard fought engagement and were limited in their scope of operations by the unpredictable weather systems of the northern hemisphere, they acted as an undeniable force multiplier for the thin-stretched squadrons of the Kommersant, who deemed the experiment a triumphal success.

On the basis of their undeniable and integral contributions to the northern colonial campaigns in the following decades, the Three Wings were rapidly integrated into the corporate structure of the Kommersant. Close collaboration with the great industrial houses of the Kommersant's corporate heartlands produced ever more efficient and powerful steam-turbine powerplants for newer generations of fighters, more destructive nanodust fuel-air bombs, and more reliable and harder hitting wing cannon. As their complete and total reliance on the nanodust and industrial output of the Kommersant's core territories ensured their national loyalty, the Three Wings were permitted an unparalleled level of independence among the nations of the Kommersant, with successive generations of Chief Executive Commodore and Trade Commissioners being convinced that the mercurial airborne tribals were better left appeased with nominal tokens of independence to forestall any renewed threat of separatism or insurrection. So long as the squadrons of the Three Wings heeded the Kommersant's calls to arms in times of war and unrest, their tribes were exempted from the heavy-handed levy-conscription and trade tax demanded of all other Kommersant nations. Though they were now nominally designated the 1st Colonial Aero Corps and subordinated to the Kommersant provisional admirals in times of war, the tribes of the Three Wings continued to choose an Ace of Aces who ranked among the great lieutenants of the Chief Executive Commodore, though these latter day Aces of Aces served largely as political liaisons rather than field commanders. Despite their diminished role, these high kings of the Three Wings proved their diplomatic skill in securing significant concessions from successive Chief Executive Commodores on the backs of battlefield victories by the brave pilots of their tribes. These Aces of Aces ensured that subsequent generations of Wingmen only among the nations of the Kommersant would enjoy a monopoly on the closely guarded secrets of powered flight. Though the great Kommersant industrial houses might manufacture the high performance steam turbines, armaments packages, and duralum fuselages of the Wingmen's airframes, the free-spirited tribals would assemble and test-fly the completed attack craft in the isolated seclusion of the arid Boneyard. And far from the prying eyes of Kommersant military attaches and technical specialists, the young pilot-initiates of the Three Wings would learn the fundamentals of flight and maneuver in the deep interior of the Great Western Salt Flats.

Still, a century of close collaboration with their Kommersant rulers and liaisons has inevitably resulted in a degree of cultural assimilation. Only a handful of Wingmen among the younger age cohorts still leave pre-flight prayer offerings at the old tribal shrines to the Sky Gods of the Wild Blue Yonder, with many of their number having embraced the Common Corporate Doctrine of the Kommersant. The stylized Trade Speech of the Kommersant's corporate elite has spread even among the high colonels of the Three Wings, although the old Inglic dialect remains the preferred medium of radio communication in combat for all classes of Wingmen. Decades of subtle Kommersant propaganda and distorted myth have turned the memory of last War Between the Fleets and the Nanodust Embargo into a tale of malicious Texacoran betrayal in the minds of many modern day Wingmen, to the point that the current Chief Executive Commodore no longer fears the political repercussions of deploying his airborne legions against their historical Texacoran allies in the colonial campaigns and proxy wars of the northern hemisphere. Nevertheless, the Wingmen retain a healthy respect for the combat prowess of their former Texacoran allies. The armored Texacoran treadnoughts with their dense point-defense batteries and incendiary canister barrages have proven time and again to be extremely dangerous targets for even the swiftest flying Wingman aviator. Just as difficult for the fighter-bombers of the Wingmen to counter are the surface cruiser convoys and mobile laagers of the Afrikander nomad republics. The treacherous storm systems of the equatorial reaches keep many Afrikander republics permanently beyond the reach of Wingmen combat patrols, while the unmanned aerial survey drones and recon scans of most Orbitaaler laagers can alert them to the approach vector of Wingmen strike flights with enough early warning to plot an evasive course.

Thus, the favored targets of the Wingmen remain the irregular pirate bands of the Djong-Kok and the war fleets of the Red Empire in the colonial territories. There, the Wingmen have become a source of feared terror among those who oppose the heavy handed trade monopoly of the Kommersant. Outside of their exploits in active combat operations, the Yankee Air Pirates, as the Wingmen are colloquially known in the colonial latitudes, have developed an unsavory reputation for strafing the civilian sailskimmers of krill-fishers and coastal merchants that mistakenly wander into the exclusion zones of Kommersant trade blockades, sometimes solely out of a playful desire to break the monotony of blockade duty. Though they prefer the tribal glory that is gained in pitched aerial battle against the gun-kites and signalling balloons of Red and Djong-Kok war fleets, oftentimes the frontier squadrons of the Wingmen are assigned to punitive bombardment and strike missions in those frontier territories beyond the reach of the Kommersant's colonial gun-clipper pickets. Thus, the first and only impression of the Wingmen for many inhabitants of the northern hemisphere is to be found in the indiscriminate aerial bombardment and strafing of Djong-Kok fishing villages suspected by the Kommersant of harboring pirates or smugglers. Downed aviators of the Three Wings on colonial campaign know better than to expert merciful treatment from their captors, and thus few take to their 'chutes in hostile territory. Even among Kommersant-aligned client states and allied port-cities of the northern hemisphere territories, the arrival of the flattop aviation clippers flying the distinctive silk banners of the 1st Colonial Aero Corps often represents a fearsome omen for the innkeepers and tavern proprietors of the local bluelight districts, for the Wingmen aviators have earned a near legendary reputation for their wild behavior on shore leave in the colonial ports.

Yet for all their mistakes and missteps in a long century of colonial campaigning, the pilots of the Three Wings have become an inseparable facet of Kommersant operations in the northern hemisphere. Though they remain arrogant and aloof tribal aviators in the eyes of the other Kommersant nations, none among the ranks of the Kommersant's kosmodesantniki and gun-clipper crews would deny that in the heat of pitched battle, the arrival of a Three Wings close support flight is always a most welcome development.

***

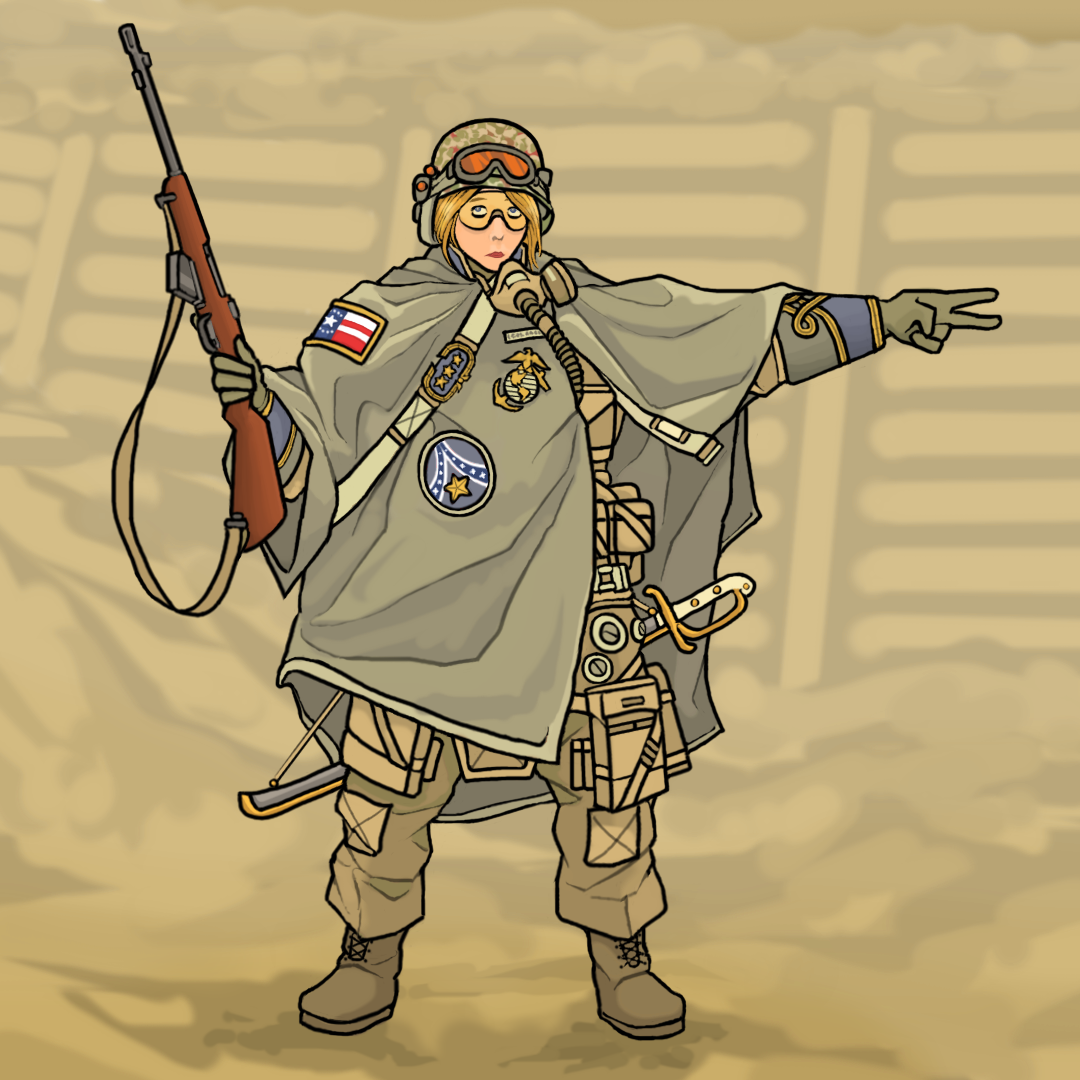

The illustration features a Three Wings aviatrix of the 1st Colonial Aero Corps at a forward archipelago airfield after returning from a successful strike sortie in the Pearl Islands Campaign. Her flight jacket and side cap are of typical tribal style and emblazoned with the hereditary unit patches and flight badges of her ancestral aerospace squadrons. Hereditary rank insignia is often worn in addition to tribal squadron affiliation, though taking a secondary precedence in prominence of display. Aviators of the Three Wings are accustomed to personalizing their flight jackets, flight gear, and headwear, with a great variety in flying goggles, tinted spectacles, neckties, silk scarves, and other accessories in evidence among all Three Wings pilots. Short trousers are the order of the day in both the arid training grounds of the Great Western Salt Flats and the sweltering humidity and heat of colonial campaigning, as long hours are often spent waiting on the flight line while squadron colonels and Kommersant military liaisons confer over pre-flight preparations in the shade of an operations tent or the bridge of a flattop gun-clipper.

The aviatrix carries a heavy ceramsteel survival knife of modern tribal origin in her utility belt and a six-shot Serrograd 7-series percussion revolver of Kommersant manufacture in her pistol holster. The survival knife is considered an essential element of the combat kit worn by Three Wings aviators, and due to its general utility as a convenient flat-bladed cutting tool, it is frequently worn on the ground as well. In comparison, the cap-and-ball Serrograd 7 percussion revolver is of rather limited utility, prized only for its relatively light weight for Three Wings pilots trying to cut every conceivable gram of excess gear from their takeoff weight. While performing adequately as a handy self-defense weapon during shore leaves in lawless colonial ports and frontier settlements, in combat over hostile territory the Serrograd 7 revolver serves as a fatal last resort for downed aviators facing the prospect of immediate capture by enemy ground or naval forces.

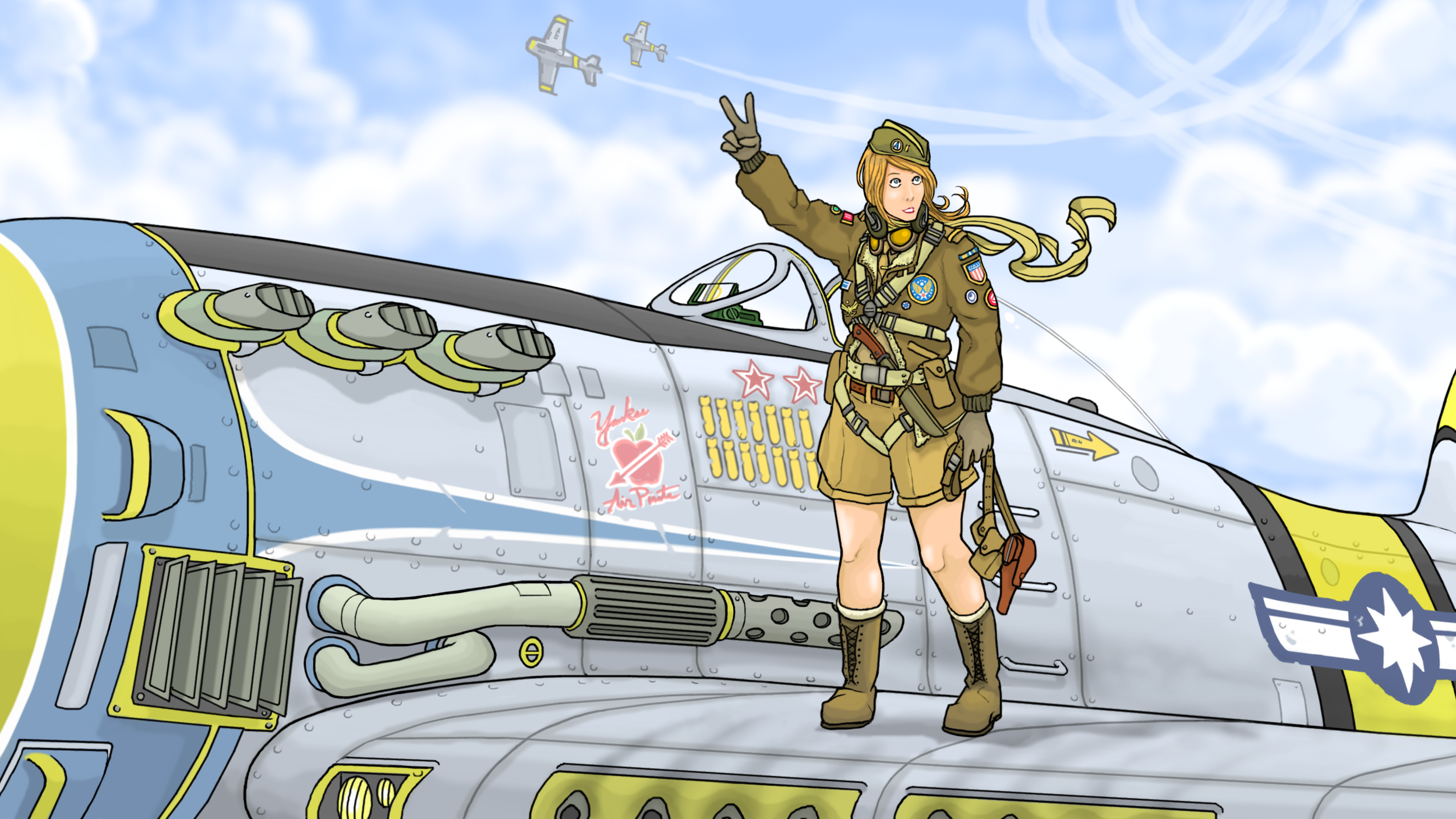

The aviatrix stands atop the port wing of her Rapier II, the latest generation model of turboprop fighter-bomber hand-fitted and assembled in the Great Western Salt Flats by General Avionics Reconstituted, the Three Wings consortium that oversees all Kommersant aviation manufacture. The semi swept-wing Rapier II fighter-bomber is scheduled to replace the aging gull-winged Comet-series of airframes in combat service, though currently only those forward-deployed squadrons in the colonial north have been reequipped and converted to the new attack craft. The Rapier II is powered by a high performance Zvesda-C steam turbine powerplant produced in the Kommersant construction yards of the New Vostok & Hyde Engineering Works. Burning a dry fuel-air mix of high-grade nanodust, Zvesda-C enables the Rapier II to reach a maximum altitude of 5000 meters and a maximum straightline cruising speed of 500 kph, though direct injection of pure nanodust fuel into the combustion reactor enables a limited maximum speed of 750 kph at the risk of rapid fuel depletion and engine damage. The duralum-ceramsteel composite alloy airframe of the Rapier II is crafted in separate wing and fuselage sections by the expert Kommersant forgemasters of Ulyanovsk Heavy Industries, and along with the pure duralum skin, are capable of shrugging off standard caliber ball rounds from conventional musketry and ground fire. Nevertheless, the airframe remains highly vulnerable to the standard anti-air incendiary canister shot employed by the better equipped military forces of the Djong-Kok and Red imperial states.

The Rapier II represents the premier fighter-bomber of the Three Wings battle squadrons not only in performance but in armaments as well. Each Rapier II is equipped with no less than sixteen M3 Windstorm .50 caliber revolver cannons. Mechanically actuated and linked to the primary power drive of the airframe's Zvesda-C steam turbine, the M3 Windstorm is the pinnacle of modern Kommersant automatic weapons design. Originally designed as crew-served weapons mounts aboard Kommersant gun-clippers, the M3 was initially thought by Kommersant tacticians to be of limited combat utility, as their requirement for an external power source prevented their forward deployment with kosmodesantniki in the field. However, once coupled to the high performance steam turbines that powered the fighter-bombers of the Three Wings, the M3 Windstorm was transformed from an auxiliary point-defense weapon with a modest automatic capability into a first-rate aerial cannon with a blisteringly high rate of fire. Although typically loaded with a general purpose mix of incendiary, armor piercing, and tracer rounds, the exact ratio of ammunition mix can be tailored by aviators to suit specific combat missions or preferences. Modular payload pylons on the underside of the Rapier II's wings allow for the deployment of several different classes of offensive systems, including a variety of unguided chemical rockets, nanodust fuel-air incendiary bombs, general purpose cluster explosives, and armor piercing bombs, all standard pattern and manufactured under contract by one of the many Kommersant weapons conglomerates.

The color scheme of the depicted Rapier II is typical of an airframe deployed in the northern hemisphere campaigns of the 1st Colonial Aero Corps, with the black-yellow-black stripes on rear fuselage, wingtip, and vertical stabilizer particular to those airframes participating in active combat operations. The blue and white engine cowling embellishment is indicative of a flight leader's airframe. The aviatrix's personal flight emblem is painted ahead of mission markings and aerial victory score. Each bomb case silhouette represents a successful strike mission, while each star marks an aerial victory scored against a tethered gun-kite or observation/signalling balloon. Aerial victories are increasingly uncommon as the Djong-Kok pirate clans and Red war fleets withdraw vulnerable aerial platforms from frontline service, making each star a highly prized trophy for the veteran combat pilots of the Three Wings. Personal and tribal airframe decorations were once ornate and highly florid affairs that decorated every exposed external surface, but in the century since the annexation of the Three Wings to the Kommersant, tribal squadron markings have been discouraged entirely and personal emblems reduced in size in order to improve the visibility of operational unit markings. The roundel painted on the rear fuselage of the airframe is unique to the 1st Colonial Air Corps and derived from the ancient emblem of the Interstellar Commerce Authority's North American Aerospace Force, symbolically acknowledging both the historical ties and modern day loyalty of the Three Wings to the ICA successor state embodied by the Kommersant.