I don't see how this changes things much. Even if you pull of this miracle Stalin trains in reinforcements and the Soviets win the next battle. Going north in 1942 does little to the Soviets except deprive them of a source of wood, fish and fur. The US would simply send their shipments in via Iran or Murmansk. The US might lose a few more freighters to U-boats but it could afford that.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

WI: Soviet Union loses the Battle of Khalkin Gol

- Thread starter A Piece of History

- Start date

In the end, the Soviets won because they were willing to pay more for victory than Tokyo was. Thing is if the Japanese were willing to pay the price the Soviets would have had their butcher's bill jacked up.

To do so was beyond both Japanese operational skill and logistical ability. They never had the option to match the Soviet forces, even had they wished to do so. The Japanese were barely able to sustain the lone division out at Khalkhin Ghol in a defensive posture as it was and when the Soviet offensive struck their hasty attempts to reinforce, which received no interference from Tokyo, were painfully slow and trivial in numbers. It wasn't until 9 September, three weeks after Zhukov's offensive begun and more than a week after the 23rd Division had been annihilated, that the Japanese had gathered the designated forces... only to find they were still grossly outmatched. That the Soviet operation was conducted on a scale the Japanese at the time considered impossible is a matter of historical record, particularly the Japanese historical record. It was only because of Soviet restraint that the Japanese didn't suffer an even worse defeat and not vice-versa.

In the end, all pointing to loss ratio does is show that the Soviet victory was hard fought. What it does not do is explain why it was a Soviet victory.

EDIT: It's also worth keeping in mind that the vast majority of sources on Nomonhan are Japanese, and I haven't yet seen a detailed English-language Soviet account of the battle. Even Coox's seminal work relies overwhelming on Japanese sources, despite still painting a grim picture of Japanese capabilities, written as it was a year before the collapse of the USSR. There are known problems with relying on sources from just one side of a battle, particularly with regards to kill claims and the size of opposing forces. If we had the same wealth of tactical sources from the Russian side we might discover that the Japanese did rather less well in battle than even they thought they did.

Last edited:

Assuming he isn't lying in a ditch after a 9mm lead poisoning in 1937-38, that is.attacks?

Zhukov.

Deleted member 1487

Numbers in all categories, Soviet willingness to escalate beyond what the Japanese government was willing to do, and the fact that Japan was balls deep in China. Of course the Kwangtung army was not in a position to fight a war, they'd have had to pull in resources from outside Manchuria to escalate. So any POD would require Japan to either not be in China already or have more forces in theater for some reason when the fight happens, which could react to the attack. Or have Tokyo willing to send reinforcements sooner for some reason (the border clashes were going on for months). Anyway my point about the loss ratios was that IF the Japanese had more forces to commit, which wouldn't have necessarily had to be that much, say an additional prepared division or two and some extra armor/aircraft/artillery, they could have probably won against the historical Soviet forces.To do so was beyond both Japanese operational skill and logistical ability. They never had the option to match the Soviet forces, even had they wished to do so. The Japanese were barely able to sustain the lone division out at Khalkhin Ghol in a defensive posture as it was and when the Soviet offensive struck their hasty attempts to reinforce, which received no interference from Tokyo, were painfully slow and trivial in numbers. It wasn't until 9 September, three weeks after Zhukov's offensive begun and more than a week after the 23rd Division had been annihilated, that the Japanese had gathered the designated forces... only to find they were still grossly outmatched. That the Soviet operation was conducted on a scale the Japanese at the time considered impossible is a matter of historical record, particularly the Japanese historical record. It was only because of Soviet restraint that the Japanese didn't suffer an even worse defeat and not vice-versa.

In the end, all pointing to loss ratio does is show that the Soviet victory was hard fought. What it does not do is explain why it was a Soviet victory.

As it was apparently Coox says that the Japanese detected the buildup but did not react.

Though again I'm not that well versed on all the specifics off hand (I haven't argued about this a while) and @BobTheBarbarian has done ungodly amounts of research on that specific battle and has the numbers.

Depends on whether they are official documents or not. The Soviet official history of WW2 is...rather loose with the facts. Still, hasn't there been something in Russian about the fighting in the Far East in 1938-39?EDIT: It's also worth keeping in mind that the vast majority of sources on Nomonhan are Japanese, and I haven't yet seen a detailed English-language Soviet account of the battle. Even Coox's seminal work relies overwhelming on Japanese sources, despite still painting a grim picture of Japanese capabilities, written as it was a year before the collapse of the USSR. There are known problems with relying on sources from just one side of a battle, particularly with regards to kill claims and the size of opposing forces. If we had the same wealth of tactical sources from the Russian side we might discover that the Japanese did rather less well in battle than even they thought they did.

Though you're certainly right, relying on only one side isn't particularly helpful, as using just the recollection of German officers captured by the Wallies in WW2 about the history on the Eastern Front shows (though it's funny reading US wartime reports on the Red Army, which venerates their military and it's prowess).

He was no where near the front as I recall, so not in a position to have that particular health issue.Assuming he isn't lying in a ditch after a 9mm lead poisoning in 1937-38, that is.

Well, it was an oblique way of saying "he got purged".He was no where near the front as I recall, so not in a position to have that particular health issue

Deleted member 1487

Gotcha...but then you should have said 7.62mm, that was the caliber the Soviets used for the NKVD TT Pistol.Well, it was an oblique way of saying "he got purged".

Though apparently Stalin's personal executioner used a .25 ACP Walther because he trusted it's reliability for...heavy use.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vasily_Blokhin#Role_in_the_Katyn_massacre

Something I've read mentioned before is that if Zhukov is in charge and loses, this could have major repercussions later on if Zhukov is executed for his failure. What would be different in the way the Soviets fought the Germans without him?

Numbers in all categories,

And the numbers were a direct result of Soviet operational-logistical superiority. The Japanese couldn't even get enough food for a single division while the Soviets were able to support everything needed for a two-corps equivalent combined-arms mechanized offensive with room to spare.

Soviet willingness to escalate beyond what the Japanese government was willing to do, and the fact that Japan was balls deep in China. Or have Tokyo willing to send reinforcements sooner for some reason (the border clashes were going on for months). Anyway my point about the loss ratios was that IF the Japanese had more forces to commit, which wouldn't have necessarily had to be that much, say an additional prepared division or two and some extra armor/aircraft/artillery, they could have probably won against the historical Soviet forces.

Your point ignores that the Japanese did historically route two more divisions, the 2nd and the 7th, as well as other elements (including additional armor and artillery) in response to the Soviet attack... only for them to prove not just inadequate to salvage the situation, but far too late. Coox comments that the increased strength was "impressive by Japanese standards... in practice, there was still a fatal inferiority in firepower vis-a-vis the Russians, especially in armour and artillery." Coox further details that despite the delay the Kwangtung Army's logistic support had been unable to stockpile sufficient materiel to take the well supported Soviets head on, and so the plan was for stealthy attacks only at night, with the troops defending in the day.

Coox makes no bones about his opinion on the Japanese chances for success even for their more escalatory plans you claim the Japanese could carry out, calling their planning simplistic and their forces insufficient. In this he echoes the opinions of Japanese contemporaries: "I personally did not think the offensive would solve things," and "a couple of divisions meant nothing - like a drop of water in a vast ocean," to quote a couple of Japanese officers. The fact that the Kwangtung Army took so long to even gather so little is a direct result of their limited logistic backbone, on top of poor intelligence assessment and insufficient contingency planning. The Japanese were left outnumbered and outgunned at Nomonhan not because of intransigence from Tokyo, but because they were operationally outmaneuvered and they lacked the logistical ability to move and support anywhere near the forces the Soviets could anywhere near as rapidly. The 23rd Division died alone (aside from some ineffective actions by the few elements of the 7th Division that were able to make it in time) because the Kwangtung lacked the operational skill and the logistical ability to send it sufficient aid in any sort of reasonable timeframe, not because of supposed intransigence from Tokyo.

As it was apparently Coox says that the Japanese detected the buildup but did not react.

Yes, and he also says the reason they did not react is because nothing could be done about it. He specifically states that the Soviet operation was conducted on a scale the Japanese considered impossible, China or no China, with "Soviet truck usage dwarfed IJA capabilities and thinking at the time." Coox concludes the section with the words, "IJA intelligence experts remain awed to this day by the amount of men and materiel moved so ruthlessly." He goes on to add later "the impressive degree of Soviet battlefield mobility enabled large-scale hostile forces to operate in a broad and desolate area 700km from the nearest railhead for two months. As soon as the Russians learned of the Japanese enveloping offensive, they broke its back by committing mechanized corps that advanced 100km in a day. IJA forces, suffering from inferior mobility, tried to check the superior mechanized units but were smashed one after another. Whereas the foe was able to move freely, the Japanese were contained." Zhukov, managed to assemble a corps-and-a-half size force and all their food, fuel, ammunition, ash, and trash in about a month. The Japanese couldn't even properly move and supply two infantry divisions in the same amount of time. The conclusion is inescapable: the Japanese were logistically badly outmatched.

Depends on whether they are official documents or not. The Soviet official history of WW2 is...rather loose with the facts.

Soviet official history is not necessarily the same thing as Soviet official documents. I mean, obviously the former constitutes a form of the latter, but what we're looking for would be stuff the Soviets didn't release publicly since that is the stuff which is bluntly the facts.

Still, hasn't there been something in Russian about the fighting in the Far East in 1938-39?

Most of the stuff I've seen tends to rely on more second-hand sources, like Zhukov's memoirs, or official histories rather then more direct use of archival material.

Last edited:

Frankly the JIA was not the Heer. it was not at all impressive against first line European/American Armies. The JIA was impressive in its ability to get its soldiers to make suicidal attacks and little else. It was basically a WWI army that learned little from WWI . I agree with Nuker, if by some miracle the Japanese win the Russians send more troops. If for some bizarre reason the Japanese attack Siberia cutting the Soviets off from salmon and moose meat it isn't going to change a whole hell of a lot.

Keep in mind that the casualty disparity actually wasn't that bad at Khalkin Gol. Highly suspect Soviet estimates put it at about a 2 to 1 level in their favor. Other estimates put it at about 2 to 3 in favor of the Japanese.

But the biggest issue for the Japanese, besides the tactical inferiority, was the fact that it was a largely non-state sanctioned act. Japanese air support for the effort would have been a lot better had the Imperial War Cabinet been consulted more, and so would reinforcements. The numbers of men engaged (28K-38K) for the Japanese was woefully too small for the task. Then again, Manchurian infrastructure was bad enough that its possible they could not have sustained more men in the area.

To make them win, you need to at least triple the Japanese present and use a much more experienced division than the 23rd for the main thrust. Yes, the Soviets had a mechanized edge, but they still suffered quite a few casualties, and their reflection of the battle was that they needed to keep a lot of men in the region rather than just writing it off.

But the biggest issue for the Japanese, besides the tactical inferiority, was the fact that it was a largely non-state sanctioned act. Japanese air support for the effort would have been a lot better had the Imperial War Cabinet been consulted more, and so would reinforcements. The numbers of men engaged (28K-38K) for the Japanese was woefully too small for the task. Then again, Manchurian infrastructure was bad enough that its possible they could not have sustained more men in the area.

To make them win, you need to at least triple the Japanese present and use a much more experienced division than the 23rd for the main thrust. Yes, the Soviets had a mechanized edge, but they still suffered quite a few casualties, and their reflection of the battle was that they needed to keep a lot of men in the region rather than just writing it off.

Keep in mind that the casualty disparity actually wasn't that bad at Khalkin Gol. Highly suspect Soviet estimates put it at about a 2 to 1 level in their favor. Other estimates put it at about 2 to 3 in favor of the Japanese.

Which just means the Soviet victory was hard fought. That you fight well in your losing battles doesn't change the fact their losing battles.

But the biggest issue for the Japanese, besides the tactical inferiority, was the fact that it was a largely non-state sanctioned act.

In practice, this meant little. The Kwangtung was able to freely use the air and ground power available to them as they chose throughout the battle. Even when IGHQ tried to put it's foot down in June by ordering the Kwangtung Army to cease air operations, the Kwangtung Army simply ignored the order: Coox records a number of air operations in July and August by the IJAAF. It wasn't until September 14th that Tokyo was able to exert any control over matters and to do that they had to fly their own men directly in to berate the commander of the Kwantung Army into coming to heel. What it really came down too is that the IJA didn't have the logistical ability or aptitude for operational planning and maneuver to field and supply the forces needed to halt the Soviets.

Then again, Manchurian infrastructure was bad enough that its possible they could not have sustained more men in the area.

The issue goes beyond infrastructure, beyond even resources, and straight into how the Japanese conceived of operations and logistics. As Coox put it: "Japanese operations officers, obsessed with battle, tended to regard logistics as a bore, in part because logisticians were cautious and deliberate by nature and not cast in the glamorous mould of the saber-wielding warrior. "Logistics follows operations," an IJA saying went; the logistical annexes of operational plans were chronically thin. At least until the Kantokuen buildup of 1941, the Kwangtung Army was seriously deficient in logistical underpinning, most notably with respect to ammunition supply and organic motorization."

Even after the build-up, though, Coox noted serious continuing deficiencies: for instance, the IJA massively increased the size of the Kwangtung Army in mid 1941 from a forward strength of 250,000 to 710,000 soldiers but paid insufficient attention to how those troops would actually survive out in northern Manchuria over the winter. When a quartermaster dared raise the issue, his superior hit him. That's the mark of a totally amateurish attitude towards logistics. Ultimately the Japanese never attacked Russia, and 88,000 troops were transferred south, which alleviated the billeting problem but it's still clear the Japanese Army had very poor attitudes towards proper logistical planning, even in 1941.

In sum, Japan's problem wasn't just that it was quantitatively outclassed by its opponents (although it was, badly) but also that in using the assets it had Japan was also qualitatively quite poor. The Japanese continually mismanaged what few logistic assets they had, making a bad situation even worse. This was due to a lack of co-ordination and long range planning, as well as a continual failure to realistically appraise the logistical demands of ongoing and upcoming operations. We can see this in instances beyond Khalkhin Ghol. The Japanese mismanagement of their merchant fleet is the best example, but there are others. For instance, the Japanese Army Air Force plunged into the New Guinea campaign with no long or even short range planning for how those air assets would be supported. This wasn't helped by the complete lack of co-operation between the Navy and the Army. For instance, Army aircraft requiring an engine change had to be flown three thousand miles to Manila in the Philippines, because no suitable depot existed in theatre. Since fuel was in short supply in New Guinea, this additional waste was crippling. Except the Navy had the capability to perform engine changes in Rabaul, just 300 miles off the coast, however the Navy never offered this capability to the Army (although in fairness, Navy preparations in Rabaul were so limited they could not even properly maintain their own aircraft complement). The result was that the logistic support of the New Guinea operation was ad hoc, disorganized, and wasted much of what limited resources were available.

Proper use of logistics requires sound planning and this is even more critical when you have very limited resources and outsized tasks. The Japanese consistently failed to perform this logistical planning, which tended to make bad situations immeasurably worse.

Or tactics/weapons (even if improvised) to counter Soviet armored superiority (keep in mind the Finns, with weapons crappier than the IJA units at Khalkin Gol, held off the Soviets for three months via tactics and weapons which were able to counter Soviet armored superiority until Timoshenko came along).Japan would probably need to develop a doctrine for mechanized units,

BobTheBarbarian

Banned

It would be very difficult for the Japanese to actually win the Battle of Khalkhin Gol given both the regional disparity in forces as well as the rules of engagement for both sides. Even if Tokyo opted to allow more reinforcements to be sent to General Komatsubara and lifted the ban on air strikes in Soviet territory, the Red Army and Air Force could simply reciprocate in kind since they had many more reserves on hand. In a contest of attrition in 1939, even a limited one like Khalkhin Gol, the Soviets had more stamina than the Kwantung Army. Probably the only way the IJA could 'win' the battle was if Zhukov pulled back after the Japanese offensive in July (which historically broke into the Soviet rear areas before being stopped by an armored counterattack), which would only have come on direct orders from Moscow.

However:

All of these are 'pop history' memes and need to die. Khalkhin Gol did very little to dissuade Japan from planning to attack the Soviet Union; even into 1944 (yes, while the US was wrecking their carrier fleet in the Marianas and launching B-29 raids on the Home Islands) the IJA envisioned launching a land invasion of Soviet territory should a war have broken out. Additionally, during the actual fighting at Khalkhin Gol both the Japanese tanks and infantry consistently outfought their Soviet opponents: although the BTs were better on paper than the Japanese Ha-Gos, the Yasuoka Group tankers knocked out many more Soviet vehicles in pitched engagements than they themselves lost in return, and each time the Red Army attempted infantry attacks on the Japanese positions they were slaughtered. The worst case of this was the series of probes Zhukov launched on 7/8 August to "feel out" the defenders prior to the big show on the 20th; the combined results of these were over 1,000 abandoned corpses on the Soviet side and several tanks knocked out, whereas Japanese casualties (not just killed, but casualties) numbered just 85.

On the whole, prior to Zhukov's general offensive on August 20th the battle was largely a stalemate, with the Soviets being on the receiving end of a nearly 3 to 1 casualty ratio (a ratio also present at Lake Khasan, where the Japanese were even more outnumbered and outgunned).

Coox relies heavily on Soviet-era sources for the narrative on the Red Army side, though most of the book consists of a tactical view of events from the Japanese perspective as described by many of the latter's veterans, either through direct interviews or war journals. The full breadth of information currently available to us from Soviet/Russian sources (Kolomiets, Kondrat'ev, or even the 2013 publication by the Institute of Oriental Studies as edited by E. V. Boykova), simply was not accessible to him in the 1970s and 1980s. From this limitation the reader gains an impression that the battle was much more one-sided than it actually was.

In reality the Japanese Army's claims of damage inflicted on the Soviet side were significantly understated compared to the real thing, a situation paralleled by the Finnish Army's claims in the Winter War. According to figures used by the Japanese in the aftermath of the battle, their estimate of Soviet casualties was about 18,000 ("not less" than their own) with 400 AFVs destroyed - the real figures were 27,880 and 386, respectively. The only major overclaim was in the air, where IJAAF aviators reported over 1,200 downed Red planes, more than six times the actual total. The Soviet 1st Army Group, for their part, initially gave Japanese casualties as 29,085, which was much closer to the truth than the 50 or 60 thousand often seen in "official" sources.

After the 23rd Division was encircled the Kwantung Army realized what was happening and put together a 'relief force' consisting of three divisions, elements of two more, another tank regiment, 47 37mm AT guns, a motorized mountain artillery regiment of two battalions (24 guns) 34 75mm regimental guns, two 150mm howitzer regiments, three engineer platoons, and 21 transport companies plus some auxiliary railway units with 1,500 vehicles. These finally arrived in-theater on the 8/9th of September, by which point the battle was long over. Even these units, as ObssesedNuker pointed out with reposted IXJac quotes, were still outnumbered by Zhukov's 1st Army Group and did not counter the imbalance in tanks, artillery, and logistical assets. Given the Soviets' losses (another 9,000+ since 20 August) they probably could have thrown them back on the defensive, but by that point though we're just back to paragraph 1 of my post, and the Soviets can sit on their superior supply lines to build up beyond Japan's capacity to respond, counterattack, (rinse and repeat) until the latter either gives up or goes to war. It especially didn't help that the Manchurian rail network was extremely sparse near the Mongolian frontier, forcing the IJA to rely on its limited stock of motor vehicles as it tried and failed to keep up with Zhukov's elite group.

Similarly, if these reinforcements had been there from the beginning it might have allowed the Japanese more tactical success (for example, their offensive in July probably would have succeeded in inflicting a temporary defeat on 1st Army Group), but again we're back to the situation where the Soviets can just rebuild until they have the strength to push back the IJA. As long as the USSR was determined at all costs to hold their claimed border in Mongolia there was little the Japanese could do to attrit them. The only time the Kwantung Army, as a whole, ever possessed a parity or superiority over the Soviet Far East forces was from the summer of 1941 through the first half of 1943, when it was at the height of its power.

However:

Gaijin is 100% correct, the effect of Gholkin Kol was to basically make the IJA go "NOPE! FUCK THAT SHIT! NOPE!" when anyone brought up the idea of a jaunt to the North...

...So it don't even help Germany that much apart from go to the Russians "Hey, guys your armed forces are a bit lacking in a few areas..." The Russians wouldn't even need to divert troops from the West, they had an absurd numerical advantage in men, guns and tanks and whilst the T-26 and BT-7 and co would fare badly against Panzers in 41, in 36 they are so far above what the IJA had that the Japanese might as well be fielding AV-7's...

...And as badly trained as the Soviet army was in 36, that are going to slap the IJA round the face with a house brick until it stops being funny if the Japanese fight a battle the way the Soviets want them to.

All of these are 'pop history' memes and need to die. Khalkhin Gol did very little to dissuade Japan from planning to attack the Soviet Union; even into 1944 (yes, while the US was wrecking their carrier fleet in the Marianas and launching B-29 raids on the Home Islands) the IJA envisioned launching a land invasion of Soviet territory should a war have broken out. Additionally, during the actual fighting at Khalkhin Gol both the Japanese tanks and infantry consistently outfought their Soviet opponents: although the BTs were better on paper than the Japanese Ha-Gos, the Yasuoka Group tankers knocked out many more Soviet vehicles in pitched engagements than they themselves lost in return, and each time the Red Army attempted infantry attacks on the Japanese positions they were slaughtered. The worst case of this was the series of probes Zhukov launched on 7/8 August to "feel out" the defenders prior to the big show on the 20th; the combined results of these were over 1,000 abandoned corpses on the Soviet side and several tanks knocked out, whereas Japanese casualties (not just killed, but casualties) numbered just 85.

On the whole, prior to Zhukov's general offensive on August 20th the battle was largely a stalemate, with the Soviets being on the receiving end of a nearly 3 to 1 casualty ratio (a ratio also present at Lake Khasan, where the Japanese were even more outnumbered and outgunned).

EDIT: It's also worth keeping in mind that the vast majority of sources on Nomonhan are Japanese, and I haven't yet seen a detailed English-language Soviet account of the battle. Even Coox's seminal work relies overwhelming on Japanese sources, despite still painting a grim picture of Japanese capabilities, written as it was a year before the collapse of the USSR. There are known problems with relying on sources from just one side of a battle, particularly with regards to kill claims and the size of opposing forces. If we had the same wealth of tactical sources from the Russian side we might discover that the Japanese did rather less well in battle than even they thought they did.

Coox relies heavily on Soviet-era sources for the narrative on the Red Army side, though most of the book consists of a tactical view of events from the Japanese perspective as described by many of the latter's veterans, either through direct interviews or war journals. The full breadth of information currently available to us from Soviet/Russian sources (Kolomiets, Kondrat'ev, or even the 2013 publication by the Institute of Oriental Studies as edited by E. V. Boykova), simply was not accessible to him in the 1970s and 1980s. From this limitation the reader gains an impression that the battle was much more one-sided than it actually was.

In reality the Japanese Army's claims of damage inflicted on the Soviet side were significantly understated compared to the real thing, a situation paralleled by the Finnish Army's claims in the Winter War. According to figures used by the Japanese in the aftermath of the battle, their estimate of Soviet casualties was about 18,000 ("not less" than their own) with 400 AFVs destroyed - the real figures were 27,880 and 386, respectively. The only major overclaim was in the air, where IJAAF aviators reported over 1,200 downed Red planes, more than six times the actual total. The Soviet 1st Army Group, for their part, initially gave Japanese casualties as 29,085, which was much closer to the truth than the 50 or 60 thousand often seen in "official" sources.

Anyway my point about the loss ratios was that IF the Japanese had more forces to commit, which wouldn't have necessarily had to be that much, say an additional prepared division or two and some extra armor/aircraft/artillery, they could have probably won against the historical Soviet forces.

As it was apparently Coox says that the Japanese detected the buildup but did not react.

Though again I'm not that well versed on all the specifics off hand (I haven't argued about this a while) and @BobTheBarbarian has done ungodly amounts of research on that specific battle and has the numbers.

After the 23rd Division was encircled the Kwantung Army realized what was happening and put together a 'relief force' consisting of three divisions, elements of two more, another tank regiment, 47 37mm AT guns, a motorized mountain artillery regiment of two battalions (24 guns) 34 75mm regimental guns, two 150mm howitzer regiments, three engineer platoons, and 21 transport companies plus some auxiliary railway units with 1,500 vehicles. These finally arrived in-theater on the 8/9th of September, by which point the battle was long over. Even these units, as ObssesedNuker pointed out with reposted IXJac quotes, were still outnumbered by Zhukov's 1st Army Group and did not counter the imbalance in tanks, artillery, and logistical assets. Given the Soviets' losses (another 9,000+ since 20 August) they probably could have thrown them back on the defensive, but by that point though we're just back to paragraph 1 of my post, and the Soviets can sit on their superior supply lines to build up beyond Japan's capacity to respond, counterattack, (rinse and repeat) until the latter either gives up or goes to war. It especially didn't help that the Manchurian rail network was extremely sparse near the Mongolian frontier, forcing the IJA to rely on its limited stock of motor vehicles as it tried and failed to keep up with Zhukov's elite group.

Similarly, if these reinforcements had been there from the beginning it might have allowed the Japanese more tactical success (for example, their offensive in July probably would have succeeded in inflicting a temporary defeat on 1st Army Group), but again we're back to the situation where the Soviets can just rebuild until they have the strength to push back the IJA. As long as the USSR was determined at all costs to hold their claimed border in Mongolia there was little the Japanese could do to attrit them. The only time the Kwantung Army, as a whole, ever possessed a parity or superiority over the Soviet Far East forces was from the summer of 1941 through the first half of 1943, when it was at the height of its power.

Deleted member 1487

Which was the result of stripping the entire region for the offensive; the Soviets were preparing for a fight, the Japanese were not. There was nothing superior with their doctrine in terms of logistics, it's just that IOTL they were willing to devote the resources to win a fight that the Japanese were not willing to escalate:And the numbers were a direct result of Soviet operational-logistical superiority. The Japanese couldn't even get enough food for a single division while the Soviets were able to support everything needed for a two-corps equivalent combined-arms mechanized offensive with room to spare.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battles_of_Khalkhin_Gol#June:_Escalation

Both sides began building up their forces in the area. Soon, Japan had 30,000 men in the theater. The Soviets dispatched a new corps commander, Comcor Georgy Zhukov, who arrived on 5 June and brought more motorized and armored forces (I Army Group) to the combat zone.[26] Accompanying Zhukov was Comcor Yakov Smushkevich with his aviation unit. J. Lkhagvasuren, Corps Commissar of the Mongolian People's Revolutionary Army, was appointed Zhukov's deputy.

On 27 June, the Japanese Army Air Force's 2nd Air Brigade struck the Soviet air base at Tamsak-Bulak in Mongolia. The Japanese won this engagement, but the strike had been ordered by the Kwantung Army without getting permission from Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) headquarters in Tokyo. In an effort to prevent the incident from escalating,[27] Tokyo promptly ordered the JAAF not to conduct any more air strikes against Soviet airbases.[28]

Throughout June, there were reports of Soviet and Mongolian activity on both sides of the river near Nomonhan and small-scale attacks on isolated Manchukoan units. At the end of the month, the commander of the 23rd Japanese Infantry Division, Lt. Gen. Komatsubara, was given permission to "expel the invaders".

So an authority, this article doesn't clarify whom, allowed the 23rd division to attack. Which they did. And were stopped by superior Soviet forces, but inflicted heavier losses than the took:

The Japanese disengaged from the attack on 25 July due to mounting casualties and depleted artillery stores. By this point they had suffered over 5,000 casualties between late May and 25 July, with Soviet losses being much higher but more easily replaced.[28][39] The battle drifted into a stalemate.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battles_of_Khalkhin_Gol#August:_Soviet_counterattack

With war apparently imminent in Europe, Zhukov planned a major offensive on 20 August to clear the Japanese from the Khalkhin Gol region and end the fighting.[40]Zhukov, using a fleet of at least 4,000 trucks (IJA officers with hindsight dispute this, saying he instead used 10,000 to 20,000 motor vehicles) transporting supplies from the nearest base in Chita (600 kilometres (370 mi) away)[8] assembled a powerful armored force of three tank brigades (the 4th, 6th and 11th), and two mechanized brigades (the 7th and 8th, which were armored car units with attached infantry support). This force was allocated to the Soviet left and right wings. The entire Soviet force consisted of three rifle divisions, two tank divisions and two more tank brigades (in all, some 498 BT-5 and BT-7 tanks[41]), two motorized infantry divisions, and over 550 fighters and bombers.[42] The Mongolians committed two cavalry divisions.[43][44][45]

In comparison, at the point of contact the Kwantung Army had only General Komatsubara's 23rd Infantry Division, which with various attached forces was equivalent to two light infantry divisions. Its headquarters had been at Hailar, over 150 km (93 mi) from the fighting. Japanese intelligence, despite demonstrating an ability to accurately track the build-up of Zhukov's force, failed to precipitate an appropriate response from below.[46] Thus, when the Soviets finally did launch their offensive, Komatsubara was caught off guard.[46][47]

......

By contrast, Tokyo's oft-stated desire that it would not escalate the fighting at Khalkhin-Gol proved immensely relieving to the Soviets, who were free to hand-pick select units from across their entire military to be concentrated for a local offensive without fear of Japanese retaliation elsewhere.[52]

After it was already decided and only the 7th Division had a FRACTION of their forces actually committed to relief attacks. Then Tokyo intervened to stop plans to commit the division:Your point ignores that the Japanese did historically route two more divisions, the 2nd and the 7th, as well as other elements (including additional armor and artillery) in response to the Soviet attack... only for them to prove not just inadequate to salvage the situation, but far too late. Coox comments that the increased strength was "impressive by Japanese standards... in practice, there was still a fatal inferiority in firepower vis-a-vis the Russians, especially in armour and artillery." Coox further details that despite the delay the Kwangtung Army's logistic support had been unable to stockpile sufficient materiel to take the well supported Soviets head on, and so the plan was for stealthy attacks only at night, with the troops defending in the day.

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Batai...etour_sur_les_positions_d'avant_mai_et_bilans

On August 30, 1939, the Kwantung Army received a clear order from the Imperial Staff to prepare for the end of hostilities. The Japanese military leadership in Manchuria trying to save time and deploy the rest of the 7th Division of the border, hoping to take the offensive on 9 September 57 , but on 3 September , the most direct orders still manage him suspend offensive operation. After a final request for counter-attack, strict orders are given to the Kwantung Army on 6 September , with an explicit quote from the Emperor's willingness to retreat, and to accept the resignation of some generals. 57. The head of the Kwantung army is relieved 40 .

Trying to attack hastily to relieve and already defeated division is explicitly not what I was talking about; instead what I'm suggesting is in late July/early August those forces are sent along with more supply elements to sustain them. The problem was that IOTL Tokyo would not allow that. Kwantung army did not have THAT much freedom, especially if it required additional resources outside their command area, which was NOT a problem the Soviets had.

Again you're talking about OTL where Tokyo was starving Kwantung of resources to avoid escalating the fight. Since we are discussing a potential for an ATL where Kwantung has the resources to win, per OP, then we also have to discuss Kwangtung getting the resources outside their command to have the means to win. You're right (AFAIK) that they lacked the resources in their command area to fight on fair terms, while the Soviets got all Zhukov wanted, in a scenario where they have the ability to win they'd be getting outside resources and sending them in a timely fashion to the front.

That was because the Kwantung Army was being throttled by Tokyo. Tokyo was explicitly trying to avoid escalating the conflict and knew that Kwantung was a trouble making organization, so they were only given the resources to do their job garrisoning Manchuria, not start a major war with the Soviets. Again totally different than the Soviets, who got a special order to do so from Moscow and non-theater resources. This is why the Soviets could concentrate the equivalent of 10 divisions hundreds of KM from the nearest rail head, while the 23rd division was effectively out of supply.Coox makes no bones about his opinion on the Japanese chances for success even for their more escalatory plans you claim the Japanese could carry out, calling their planning simplistic and their forces insufficient. In this he echoes the opinions of Japanese contemporaries: "I personally did not think the offensive would solve things," and "a couple of divisions meant nothing - like a drop of water in a vast ocean," to quote a couple of Japanese officers. The fact that the Kwangtung Army took so long to even gather so little is a direct result of their limited logistic backbone, on top of poor intelligence assessment and insufficient contingency planning. The Japanese were left outnumbered and outgunned at Nomonhan not because of intransigence from Tokyo, but because they were operationally outmaneuvered and they lacked the logistical ability to move and support anywhere near the forces the Soviets could anywhere near as rapidly. The 23rd Division died alone (aside from some ineffective actions by the few elements of the 7th Division that were able to make it in time) because the Kwangtung lacked the operational skill and the logistical ability to send it sufficient aid in any sort of reasonable timeframe, not because of supposed intransigence from Tokyo.

The Soviets had to use all of those logistics resources because they were further from their rail heads.Yes, and he also says the reason they did not react is because nothing could be done about it. He specifically states that the Soviet operation was conducted on a scale the Japanese considered impossible, China or no China, with "Soviet truck usage dwarfed IJA capabilities and thinking at the time." Coox concludes the section with the words, "IJA intelligence experts remain awed to this day by the amount of men and materiel moved so ruthlessly." He goes on to add later "the impressive degree of Soviet battlefield mobility enabled large-scale hostile forces to operate in a broad and desolate area 700km from the nearest railhead for two months. As soon as the Russians learned of the Japanese enveloping offensive, they broke its back by committing mechanized corps that advanced 100km in a day. IJA forces, suffering from inferior mobility, tried to check the superior mechanized units but were smashed one after another. Whereas the foe was able to move freely, the Japanese were contained." Zhukov, managed to assemble a corps-and-a-half size force and all their food, fuel, ammunition, ash, and trash in about a month. The Japanese couldn't even properly move and supply two infantry divisions in the same amount of time. The conclusion is inescapable: the Japanese were logistically badly outmatched.

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bataille_de_Khalkhin_Gol

Although the battlefield is almost 750 km away from the nearest railway, Zhukov is well prepared, especially thanks to the use of an impressive number of trucks: his fleet of 2,600 vehicles is further strengthened. by 1625 trucks further in mid-August, as well as buses, rare commodity in the Soviet Union 26 . This truck noria will allow him to bring to work a force far superior to that of the Japanese, not in infantry but in artillery and armored vehicles. The transfer from Ulaanbaatar lasts five days on roads in poor condition, "through one of the most inhospitable areas of the world"26 . Given the field problem, Komatsubara and his superiors do not consider such an effort possible and seriously underestimate the Soviets and their ability to fight a long battle.

Zhukov has before his counter-attack about 57,000 soldiers , supported by powerful artillery and many tanks 40 .

The Japanese did not need that many to sustain similar forces because rail was closer, they just didn't assign sufficient resources to the job because they weren't planning on a massive clash with the Soviets.

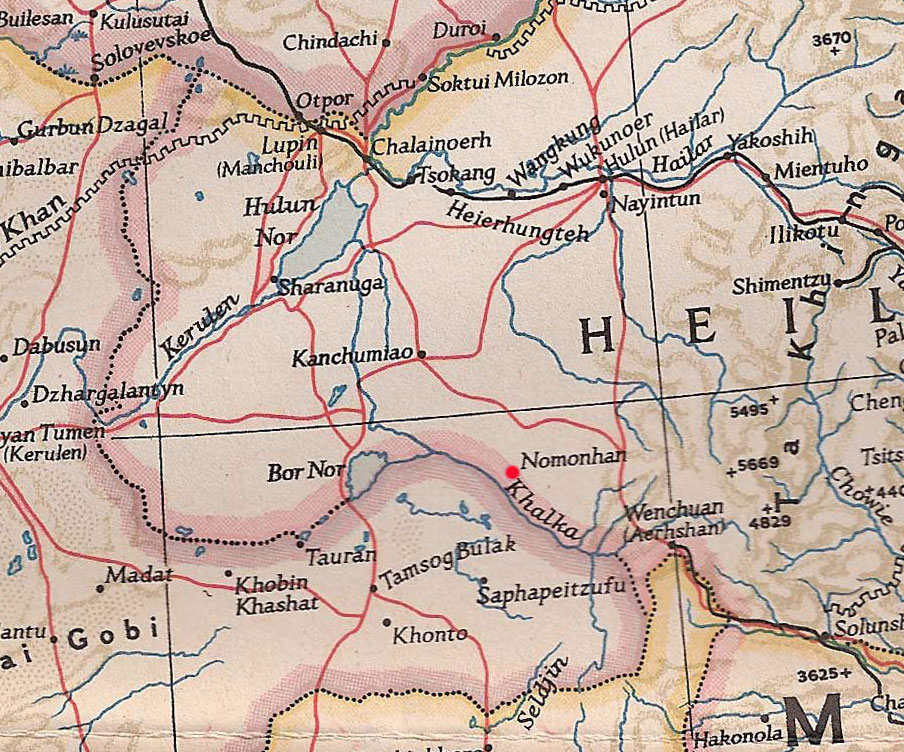

More detailed map:

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/2a/Manchuria.jpg

Note the location of the Wenchuan rail head above.

Plus of course the Japanese were not motorizing occupation divisions.

Also it was meant as a rear guard, delaying division in the event of war to allow the actual combat divisions to mobilize. Per a poor translation of the Japanese wikipedia article:

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/第23師団_(日本軍)

Anxiety of the 23rd division is that there is no practical experience in the new formation and the refinement is not high. In addition, although the West Border was judged that the threat of the Soviet Union was not so high, it is not in the environment where you concentrate on training training. It is a rear guard division so the knitting equipment is next. It was 3 units of division to expect infantry capacity shortage.

Together with the 15th , 17th , 21st and 22nd divisions in 1938 (Showa 13th) in April , it is an infantry three regiment formation division organized in Kumamoto for the back guard of the Kwantung Army .

In the situation at the time of formation, there were only two permanent divisions, including Konoe Division, in the inner area, one in Korea, five in Kwantung Army, and most of the permanent division and special division in China It was. In addition, three special divisions that had been included in the mobilization plan last year have been damaged in the maternal permanent division, the organization is impossible owing to the replenishment, and they can not be included in the mobilization plan in the Showa 13 year It was.

The Kwantung Army is in a state of great anxiety against the war against the Soviet Union, this 5-division is for the backward guard, and letting the permanent division concentrate on the front line by separating the backward direction of the front line in the pocket of little troops, It was organized to improve power.

That said I'm not arguing that the Japanese military was particularly forward thinking. Clearly the Soviets were much closer to the state of the art technologically and operationally. Still despite their massive superiority they suffered quite badly to win against a newly founded division of border guards, who's mission in the event of a major war was to fall back. The head of the Kwangtung army was sacked over this for allowing the fight to start and escalate, while Tokyo had to intervene and shut down the escalating war plans of the Kwantgung army.

Deleted member 1487

First of all thank you for commenting and your cogent response.After the 23rd Division was encircled the Kwantung Army realized what was happening and put together a 'relief force' consisting of three divisions, elements of two more, another tank regiment, 47 37mm AT guns, a motorized mountain artillery regiment of two battalions (24 guns) 34 75mm regimental guns, two 150mm howitzer regiments, three engineer platoons, and 21 transport companies plus some auxiliary railway units with 1,500 vehicles. These finally arrived in-theater on the 8/9th of September, by which point the battle was long over. Even these units, as ObssesedNuker pointed out with reposted IXJac quotes, were still outnumbered by Zhukov's 1st Army Group and did not counter the imbalance in tanks, artillery, and logistical assets. Given the Soviets' losses (another 9,000+ since 20 August) they probably could have thrown them back on the defensive, but by that point though we're just back to paragraph 1 of my post, and the Soviets can sit on their superior supply lines to build up beyond Japan's capacity to respond, counterattack, (rinse and repeat) until the latter either gives up or goes to war. It especially didn't help that the Manchurian rail network was extremely sparse near the Mongolian frontier, forcing the IJA to rely on its limited stock of motor vehicles as it tried and failed to keep up with Zhukov's elite group.

Similarly, if these reinforcements had been there from the beginning it might have allowed the Japanese more tactical success (for example, their offensive in July probably would have succeeded in inflicting a temporary defeat on 1st Army Group), but again we're back to the situation where the Soviets can just rebuild until they have the strength to push back the IJA. As long as the USSR was determined at all costs to hold their claimed border in Mongolia there was little the Japanese could do to attrit them. The only time the Kwantung Army, as a whole, ever possessed a parity or superiority over the Soviet Far East forces was from the summer of 1941 through the first half of 1943, when it was at the height of its power.

In terms of the Soviet forces I'm seeing that they had only 57,000 men, which is sounds like the Japanese relief force would match or, at least given the loss ratios, have been able to outfight what the Soviets had. Losses to what the Soviet had, their elite force, would only leave the '2nd string' that wasn't selected to be part of the 'elite' 1st Army Group, which means if the fight continues and the Soviets come back, it is only with what they can scrape together from other Far East Soviet forces. I'd think that the Soviet resources were going to get pretty drained having to maintain logistics 750km from their nearest rail hub while casualties to their best troops would quickly leave them with inferior and even worse performing replacements, while the Japanese are just bringing in their on hand 'A Team', rather than the 'C-Team' green 23rd division.

Which was the result of stripping the entire region for the offensive; the Soviets were preparing for a fight, the Japanese were not.

The Soviets proved able to mass this force far faster in a shorter span of time (roughly half the assault force was allocated and moved into position in a span of fifteen days, possibly less). The Kwangtung Army, having full authority over the forces within the entirety of Manchuria remit and little-to-no oversight from Tokyo, would have been free to use their own resources as they saw fit. They did.

There was nothing superior with their doctrine in terms of logistics,

"Soviet truck usage [at Nomonhan] dwarfed IJA capabilities and thinking at the time; the Japanese regarded 100 kilometers as "far" and 200 trucks as "many." To sustain one day of Japanese operations at Nomonhan necessitated the logistical equivalent of 320 truckloads operating across the less than 200 kilometers from Hailar. From the Trans-Baikal District, the Russians would need at least 1,300 daily truckloads. Since the Soviet command achieved its full and sustained buildup, however, IJA military observers have become convinced with the benefit of hindsight that the Russians may actually be understating the case when they say they used "only" about 4,000 trucks... In any event, IJA intelligence experts remain awed to this day by the amount of men and materiel moved so ruthlessly." [Coox, p.580]

When the practice of one sides logistical resources dwarfs not just the practice, but the theory of the other side, it is quite clear who has the superior logistical doctrine. Quotes from Coox and elsewhere, pretty much every academic you care to name has made similar remarks, fully back my statements.

After it was already decided and only the 7th Division had a FRACTION of their forces actually committed to relief attacks.

Which further proves my point: the Japanese couldn't get even a single division out there in a single week. Heck, they couldn't even get it entirely out there after nearly a month. On the other hand, the Soviets were able to move a force nearly three times the size with far more artillery and armor in less then 15 days.

Then Tokyo intervened to stop plans to commit the division:

Orders which Coox makes clear were ignored. As late as September 12th, the Kwangtung Army was undertaking hostile action against the Soviets when a detachment of the 4th Division also conducted a raid on Soviet positions south of Nomonhan. It wasn't until IGHQ personnel were directly flown in a few days later to start shouting orders in person that the Kwangtung Army was reigned in.

The Japanese did not need that many to sustain similar forces because rail was closer, they just didn't assign sufficient resources to the job because they weren't planning on a massive clash with the Soviets.

That the Japanese proved incapable of sustaining an inferior force to the Soviets despite being closer to their own railhead alone is enough to directly contradict any assertion that the Japanese could have matched Soviet forces. And the Kwangtung Army (who were the ones in control in Manchuria and at Khalkhin Ghol, regardless of what Tokyo said) was planning on a massive clash with the Soviets... that's why the 23rd division was even there in the first place.

That was because the Kwantung Army was being throttled by Tokyo.

You have repeatedly asserted this, but at no point have your demonstrated that Tokyo withdrew assets from the Kwangtung Army, which is what it would have taken to throttle them, or that the Kwangtung Army actually listened to Tokyo's orders to it in regard to Khalkhin Ghol prior to mid-September. That no additional forces were shifted on the Japanese side of the border is on the Kwangtung Army, not Tokyo.

Last edited:

Deleted member 1487

Sure, if you dedicate all the forces to a specific commander who is put in place to attack and destroy a specific force you can achieve a lot. The Japanese were belatedly given permission by some higher level of command to conduct a local offensive in July with restrictions on what their forces could do (IJA air attacks on Soviet airbases) and no reinforcements. Kwangtung wasn't trying to do more than fight a small boarder clash they though the 23rd division had in hand; Kwangtung and Moscow approached the situation very differently, which is why the Soviets acted as if they were at war, while the 23rd division and Kwangtung command acted as if they were at most fighting a limited border skirmish.The Soviets proved able to mass this force far faster in a shorter span of time (roughly half the assault force was allocated and moved into position in a span of fifteen days, possibly less). The Kwangtung Army, having full authority over the forces within the entirety of Manchuria remit and little-to-no oversight from Tokyo, would have been free to use their own resources.

Sure, the Soviets were IOTL planning on doing something completely different from what the Japanese were doing. Also the Japanese rail head was vastly closer to their border than the Soviets'. Moscow allowed Zhukov to use all the resources he wanted from all over the entire region and outside it, while Kwangtung told a single border guard division to deal with the Soviets near the border with forces at their own disposal. 200 trucks is many and 100km is far for a single division operating on the border as a guard/tripwire force. Clearly Kwangtung and the 23rd Division had no idea what they were dealing with in July and by August Kwangtung didn't really understand what was coming considering they largely left the 23rd division by itself until it was far too late."Soviet truck usage [at Nomonhan] dwarfed IJA capabilities and thinking at the time; the Japanese regarded 100 kilometers as "far" and 200 trucks as "many." To sustain one day of Japanese operations at Nomonhan necessitated the logistical equivalent of 320 truckloads operating across the less than 200 kilometers from Hailar. From the Trans-Baikal District, the Russians would need at least 1,300 daily truckloads." [Coox, p.580]

When the practice of one sides logistical resources dwarfs not just the practice, but the theory of the other side, it is quite clear which side has the superior logistical doctrine. Quotes from Coox fully back my statements.

So comparing the Soviet and Japanese effort isn't comparing the pinnacle of logistics theory or doctrine, but simply one of resources committed and concept of what was even going on; the Soviets wanted a massive victory and were willing to escalate to whatever degree necessary using all the resources they could muster, while the Japanese were just engaging a limited border skirmish without the intention of a major escalation. Kwangtung took no special interest in the situation, as they barely sent any help until after the Soviets went all in, while Tokyo was trying to stop things.

Right, because again Kwantung wasn't aware the extent of what the Soviets were willing to do; before they could actually react to a force the Soviets had been assembling for months Tokyo stepped in and fired the commander of Kwantung Army and called off the offensive actions he ordered.Which further proves my point: the Japanese couldn't get even a single division out there in a single week when the Soviets were able to move a force nearly three times the size with far more artillery and armor in less then 15 days.

So Tokyo stopped things entirely after a single raid, firing the army commander and reigning in the entire army finally.Orders which Coox makes clear were ignored. As late as September 12th, the Kwangtung Army was undertaking hostile action against the Soviets when a detachment of the 4th Division also conducted a raid on Soviet positions south of Nomonhan. It wasn't until IGHQ personnel were directly flown in a few days later to start shouting orders in person that the Kwangtung Army was reigned in.

They didn't try to. The Soviets planned for months for complex military campaign, Kwangtung didn't plan on doing more than skirmish with local resources. Funny what happens when one side decides to fight a war and the other doesn't realize they're doing more than local skirmishing. The Japanese didn't even try until after it was clear what the Soviets were willing to do and as they started to match the Soviet build up they were shut down before significant offensive action.The Japanese proved incapable of sustaining an inferior force to the Soviets despite being closer to their own railhead. That alone is enough to directly contradict any assertion that the Japanese could have matched Soviet forces.

Throttled does not mean withdraw, it means limit how much they are sent in the first place. Kwantung listened to Tokyo in September when they stopped the fighting by fiat and ended up firing the commander of that army. Beyond that they put a prohibition on air attacks on Soviet territory in June. The IJA listened.You have repeatedly asserted this, but at no point have your demonstrated that Tokyo withdrew assets from the Kwangtung Army, which is what it would have taken to throttle them, or that the Kwangtung Army actually listened to Tokyo's orders to it.

BobTheBarbarian

Banned

First of all thank you for commenting and your cogent response.

In terms of the Soviet forces I'm seeing that they had only 57,000 men, which is sounds like the Japanese relief force would match or, at least given the loss ratios, have been able to outfight what the Soviets had. Losses to what the Soviet had, their elite force, would only leave the '2nd string' that wasn't selected to be part of the 'elite' 1st Army Group, which means if the fight continues and the Soviets come back, it is only with what they can scrape together from other Far East Soviet forces. I'd think that the Soviet resources were going to get pretty drained having to maintain logistics 750km from their nearest rail hub while casualties to their best troops would quickly leave them with inferior and even worse performing replacements, while the Japanese are just bringing in their on hand 'A Team', rather than the 'C-Team' green 23rd division.

In my opinion the Japanese relief force probably would have pushed the Soviets back on the defensive, but it basically would have been a larger version of the former's July Offensive in which the IJA spearheads were checked by superior numbers of Soviet tanks and artillery. It would have re-established the stalemate, but it wouldn't have settled the issue. Then you have to consider that the Japanese relief force contained elements that came from the other side of Manchuria, weakening their position there, and that the Soviets still had considerable mechanized forces in-theater beyond what they committed to Nomonhan (potentially over 1,000 additional operational tanks between the rest of the TransBaikal Military District and the Far East Front), which they wouldn't need to worry about skimming from since the Japanese relief force already weakened their own units opposite them.

We do, however, need to consider the state of Soviet logistics as well as the atmosphere in the Kremlin: it took Zhukov the better part of two months to build up the force that he had, and he did so by amassing motor vehicles gathered from across the Trans Baikal region. If we accept that he needed 4,000 cargo trucks to sustain this force, doubling (let alone tripling it) would have required him to increase his motor pool by a similar ratio, which might not have been possible without drawing from European Russia and in any regard would have taken a good deal of time to manage. This is especially problematic since by this time the Soviets were already involved in Poland and were about to be heavily committed to the "Winter War" in Finland, which was marred by a gross deficiency in Soviet motor vehicles. Theoretically in a vacuum the USSR would always be able to trump the 1939 Kwantung Army because of its greater standing force, but if the Japanese could drag out the conflict into September politics might have started to play a part. Perhaps if the Kwantung Army had gone all-in from the beginning and prevented the 23rd Division from being encircled, Stalin might not have seen the buildup necessary to achieve a favorable ratio over them (and the exponentially increasing risk of all-out war with Japan) as worth it bearing in mind his designs in Europe.

This is all just me thinking out loud, but there was much more to this than just adding up numbers for both sides and comparing them to each other; perhaps I spoke too soon in that regard.

Share: