Chapter 1: The Spark of Revolution

Chapter 1: The Spark of Revolution

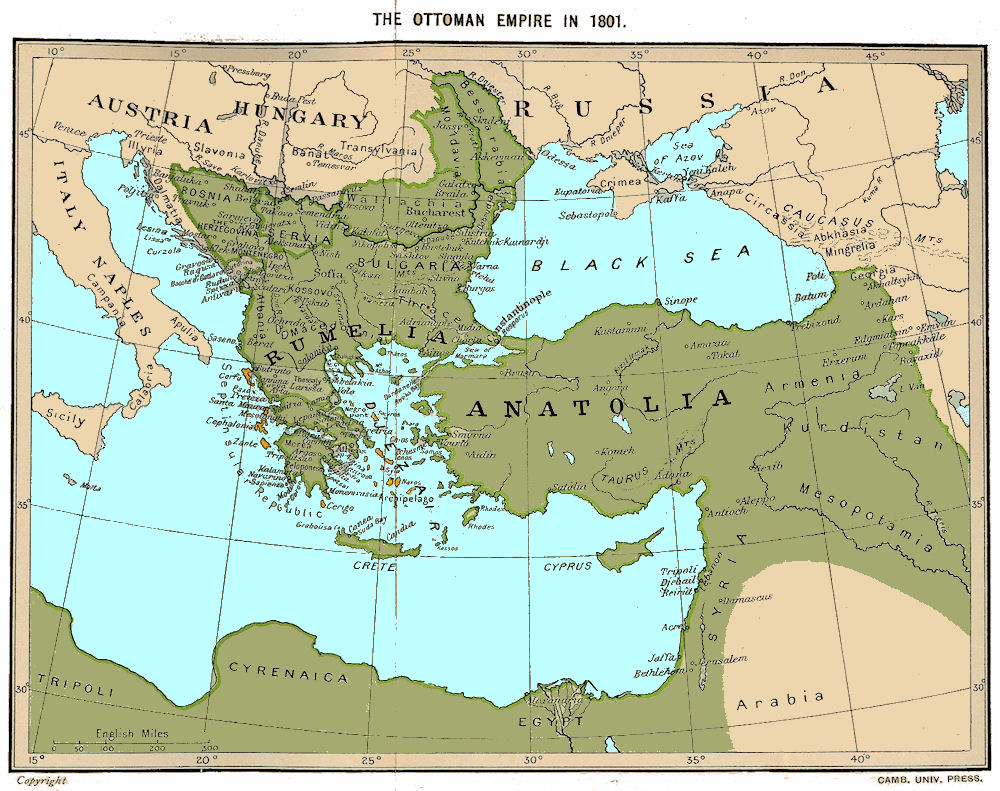

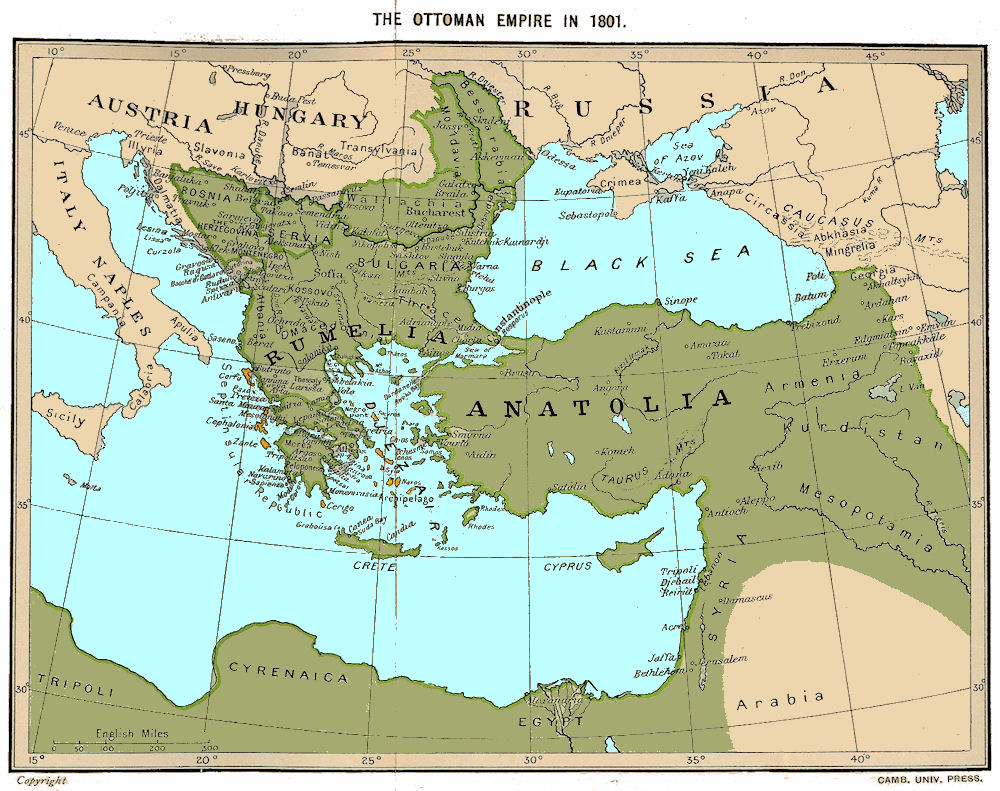

The Ottoman Empire, 1801

On the 22nd of February 1821, the Phanariot Alexander Ypsilantis crossed the Pruth River into the Danubian Principality of Moldavia and in doing so sparked an open revolt against the Ottoman Empire. Across all of Rumelia, Greeks rose in armed rebellion against their oppressors in the name of God, Liberty, and Hellas. Despite their valor, their efforts in the North would end in disaster when Ypsilantis and his followers were defeated on the field of battle in Wallachia. With no other choice, the Phanariot fled into exile in Austria where he would remain imprisoned for many years to come. This setback was soon followed by others in Cyprus, Macedonia, Thessaly, and Thrace. By the beginning of Fall, the rebellion was effectively dead in Northern Rumelia.

The defeat of Ypsilantis, however, did little to extinguish the fires of rebellion that had been lit across Greece. In Southern Rumelia, the Greeks achieved more lasting results as the important cities of Missolonghi, Salona, and Thebes fell to the Greeks. Even the ancient city of Athens, the birthplace of democracy, was liberated after a prolonged siege of the Acropolis. In the Aegean, the islands of Hydra, Psara, Samos, and Spetses joined the conflict, bringing with them their great wealth and their great merchant fleets which inflicted devastating losses against the Ottoman navy. But it was in the Morea where the Greeks had achieved their greatest victories.

The warlike Moreots of the Peloponnese did credit to their ancient ancestors as they swiftly beat back their hated adversary in a series of battles. Beginning with the liberation of Kalamata on the 25th of March, by the end of 1821 the entirety of the Morea had been freed from Ottoman rule with only a few remote castles along the coast remaining in Turkish hands. Even the provincial capital of the Morea, the mighty walled city of Tripolitsa had fallen to the Greeks after 8 short months. It was a great victory for the Greeks, but an even greater humiliation for the Ottoman Sultan.

In response to this latest insult, the Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II ordered his Serasker Khursid Ahmed Pasha, to crush the Greek rebels with the utmost haste and ruthlessness.[2] Should he fail, Khursid would meet the same fate as all the Sultan’s enemies, death. Obliging his angered liege, Khursid Pasha orchestrated a grand offensive against the rebel strongholds in the south during the Spring and Summer months of 1822. One army led by the Albanian general Omer Vrioni would advance through the mountains of Western Greece, where he would crush the last remaining pockets of resistance in the North. Moving south, he would then be tasked with securing the important city of Missolonghi from the rebels before crossing into the Morea at Patras.

The other army led by Mahmud Dramali Pasha would force its way south along the Aegean coast and cross the Isthmus into the Morea. From there, they would retake Corinth and Argos, break the siege in Nafplion, and then move against the rebels in Tripolitsa. With Vrioni’s force attacking from the West and Dramali’s from the East, their combined forces would overwhelm the remaining Greek partisans and extinguish the fires of the rebellion in the Morea. Their marching orders set, Dramali’s host departed from Lamia on the 5th of July, advancing south.

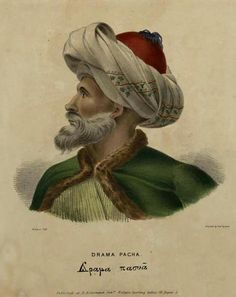

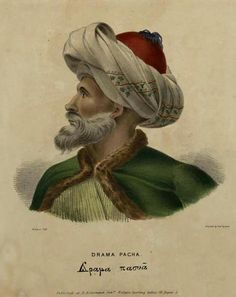

Khursid Pasha, Serasker (Commander in Chief) of the Ottoman Empire (Left) Mahmud Dramali Pasha, Commander of the Ottoman Army in Eastern Greece (Right)

Passing through Phocis, Boeotia, and Attica without so much as a shot fired in their defense, the Ottomans were lulled into a sense of security and imminent victory. This changed as soon as they crossed into the Morea. There they found the fields scorched, the wells filled in, and the livestock slaughtered to deny the Turks any supplies with which to sustain themselves. The campaign was made even more rigorous by the unusually dry summer which had left Greece in a terrible drought and the Turks in short supply of fresh water. Nevertheless, Dramali Pasha quickly established himself in the city of Corinth, where he and his officers planned their operation to crush the rebellion. Dramali was of the mind to seize Argos, the capital of the Greek traitors, while his captains, Yusuf Pasha of Evvia and Ali Bey of Argos urged him to move on Tripolitsa, to restore Ottoman rule in the Morea, and then proceed onto Patras where they would join in support of Vrioni. Dramali Pasha having come to detest Vrioni as a rival, refused to share the glory, and the spoils, with a man he considered a brigand. Ignoring the stratagems of his officers, Dramali chose to push onto Argos.

Arriving on the 24th of July, Dramali discovered much to his disappointment that the city had been abandoned with nary a shot fired in its defense. The Greek government had fled before him denying Dramali his chance at capturing them in one fell swoop. The people had similarly escaped his grasp, having fled by ship to the islands or by foot to the hills. Worst of all, the Greeks had thoroughly emptied the city of its riches and stores of grain before his arrival. While the city had been abandoned to him, the castle Larissa upon the old acropolis had not. 700 men under the command of the Phanariot Prince Demetrios Ypsilantis had holed up within its old walls, ready and willing to fight to the end if need be.

Through deception and valor, Ypsilantis managed to bravely resist the Ottomans for twelve long days and nights before fleeing under the cover of darkness in the early hours of the 5th of August. Once more, Dramali Pasha had been denied a decisive battle with which to earn his own personal glory. Adding to his woes was the failure of the Ottoman fleet to land at Nafplion, traveling instead to Patras and in the process denying his army of desperately needed supplies. To sustain themselves, Dramali dispatched several scavenging parties to scour the many surrounding vineyards for food. Several men ran afoul of Greek sharpshooters and most returned with nothing to show for their efforts. While a few managed to forage perishables from the vineyards, their goods were generally found to be unripe or riddled with maggots. Yet in their extreme hunger, the men ate these afflicted foods despite the concerns and in the process, a terrible illness began to spread through the ranks. With his foodstuffs running low, his troops beginning to fall ill, and Argos no longer of interest, Dramali Pasha reluctantly agreed to return to Corinth by way of the Dervenakia pass.

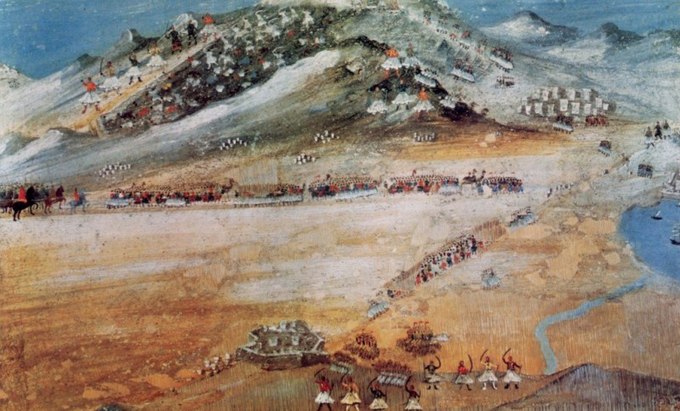

The Ottomans at ArgosNext Time: On a Horse They Fall

[1] The Oath of Agia Lavra, or The Blessing of Agia Lavra is one of the most famous legends of the Greek War of Independence. It recounts the bravery of Bishop Yermanos in defying the Ottoman governor, Khursid Pasha and declaring his opposition to the Ottoman Empire alongside the hero Theodoros Kolokotronis and the captains of the Morea. This event is considered the effective beginning of the war in the South of Greece yet there is one major problem with it, it is almost certainly a fictional event created by Francis Pouqueville, French Consul to the Ottoman Empire. Neither Bishop Yermanos nor Theodoros Kolokotronis were present at Agia Lavra on the 25th of March when this event supposedly took place, Kolokotronis was in Messenia, having just returned from the Ionian Islands, and Bishop Yermanos was likely at his home in Patras. Khursid Pasha who is also mentioned in this story as summoning Yermanos, was in Epirus and not Tripolitsa, where he made his court. Despite its dubious authenticity, the Oath of Agia Lavra is still considered an important aspect of modern Greek mythos.

[2] Khursid Ahmed Pasha was a very powerful and competent leader in the Ottoman Empire in the years prior to the Greek War of Independence. Khursid was originally born to a Christian family in Modern day Georgia and at a young age he was conscripted to the Janissaries. Due to his skill, he became Mayor of Alexandria, then governor of Ottoman Egypt and was later appointed Serasker of the Ottoman Empire during the Serbian Revolution and for his success he was made Grand Vizier (1812-1815). Khursid Pasha was once again appointed Serasker in 1820, first to defeat Ali Pasha of Ioannina, and then to defeat the Greeks.

The Ottoman Empire, 1801

The defeat of Ypsilantis, however, did little to extinguish the fires of rebellion that had been lit across Greece. In Southern Rumelia, the Greeks achieved more lasting results as the important cities of Missolonghi, Salona, and Thebes fell to the Greeks. Even the ancient city of Athens, the birthplace of democracy, was liberated after a prolonged siege of the Acropolis. In the Aegean, the islands of Hydra, Psara, Samos, and Spetses joined the conflict, bringing with them their great wealth and their great merchant fleets which inflicted devastating losses against the Ottoman navy. But it was in the Morea where the Greeks had achieved their greatest victories.

The warlike Moreots of the Peloponnese did credit to their ancient ancestors as they swiftly beat back their hated adversary in a series of battles. Beginning with the liberation of Kalamata on the 25th of March, by the end of 1821 the entirety of the Morea had been freed from Ottoman rule with only a few remote castles along the coast remaining in Turkish hands. Even the provincial capital of the Morea, the mighty walled city of Tripolitsa had fallen to the Greeks after 8 short months. It was a great victory for the Greeks, but an even greater humiliation for the Ottoman Sultan.

In response to this latest insult, the Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II ordered his Serasker Khursid Ahmed Pasha, to crush the Greek rebels with the utmost haste and ruthlessness.[2] Should he fail, Khursid would meet the same fate as all the Sultan’s enemies, death. Obliging his angered liege, Khursid Pasha orchestrated a grand offensive against the rebel strongholds in the south during the Spring and Summer months of 1822. One army led by the Albanian general Omer Vrioni would advance through the mountains of Western Greece, where he would crush the last remaining pockets of resistance in the North. Moving south, he would then be tasked with securing the important city of Missolonghi from the rebels before crossing into the Morea at Patras.

The other army led by Mahmud Dramali Pasha would force its way south along the Aegean coast and cross the Isthmus into the Morea. From there, they would retake Corinth and Argos, break the siege in Nafplion, and then move against the rebels in Tripolitsa. With Vrioni’s force attacking from the West and Dramali’s from the East, their combined forces would overwhelm the remaining Greek partisans and extinguish the fires of the rebellion in the Morea. Their marching orders set, Dramali’s host departed from Lamia on the 5th of July, advancing south.

Khursid Pasha, Serasker (Commander in Chief) of the Ottoman Empire (Left) Mahmud Dramali Pasha, Commander of the Ottoman Army in Eastern Greece (Right)

Passing through Phocis, Boeotia, and Attica without so much as a shot fired in their defense, the Ottomans were lulled into a sense of security and imminent victory. This changed as soon as they crossed into the Morea. There they found the fields scorched, the wells filled in, and the livestock slaughtered to deny the Turks any supplies with which to sustain themselves. The campaign was made even more rigorous by the unusually dry summer which had left Greece in a terrible drought and the Turks in short supply of fresh water. Nevertheless, Dramali Pasha quickly established himself in the city of Corinth, where he and his officers planned their operation to crush the rebellion. Dramali was of the mind to seize Argos, the capital of the Greek traitors, while his captains, Yusuf Pasha of Evvia and Ali Bey of Argos urged him to move on Tripolitsa, to restore Ottoman rule in the Morea, and then proceed onto Patras where they would join in support of Vrioni. Dramali Pasha having come to detest Vrioni as a rival, refused to share the glory, and the spoils, with a man he considered a brigand. Ignoring the stratagems of his officers, Dramali chose to push onto Argos.

Arriving on the 24th of July, Dramali discovered much to his disappointment that the city had been abandoned with nary a shot fired in its defense. The Greek government had fled before him denying Dramali his chance at capturing them in one fell swoop. The people had similarly escaped his grasp, having fled by ship to the islands or by foot to the hills. Worst of all, the Greeks had thoroughly emptied the city of its riches and stores of grain before his arrival. While the city had been abandoned to him, the castle Larissa upon the old acropolis had not. 700 men under the command of the Phanariot Prince Demetrios Ypsilantis had holed up within its old walls, ready and willing to fight to the end if need be.

Through deception and valor, Ypsilantis managed to bravely resist the Ottomans for twelve long days and nights before fleeing under the cover of darkness in the early hours of the 5th of August. Once more, Dramali Pasha had been denied a decisive battle with which to earn his own personal glory. Adding to his woes was the failure of the Ottoman fleet to land at Nafplion, traveling instead to Patras and in the process denying his army of desperately needed supplies. To sustain themselves, Dramali dispatched several scavenging parties to scour the many surrounding vineyards for food. Several men ran afoul of Greek sharpshooters and most returned with nothing to show for their efforts. While a few managed to forage perishables from the vineyards, their goods were generally found to be unripe or riddled with maggots. Yet in their extreme hunger, the men ate these afflicted foods despite the concerns and in the process, a terrible illness began to spread through the ranks. With his foodstuffs running low, his troops beginning to fall ill, and Argos no longer of interest, Dramali Pasha reluctantly agreed to return to Corinth by way of the Dervenakia pass.

The Ottomans at Argos

[1] The Oath of Agia Lavra, or The Blessing of Agia Lavra is one of the most famous legends of the Greek War of Independence. It recounts the bravery of Bishop Yermanos in defying the Ottoman governor, Khursid Pasha and declaring his opposition to the Ottoman Empire alongside the hero Theodoros Kolokotronis and the captains of the Morea. This event is considered the effective beginning of the war in the South of Greece yet there is one major problem with it, it is almost certainly a fictional event created by Francis Pouqueville, French Consul to the Ottoman Empire. Neither Bishop Yermanos nor Theodoros Kolokotronis were present at Agia Lavra on the 25th of March when this event supposedly took place, Kolokotronis was in Messenia, having just returned from the Ionian Islands, and Bishop Yermanos was likely at his home in Patras. Khursid Pasha who is also mentioned in this story as summoning Yermanos, was in Epirus and not Tripolitsa, where he made his court. Despite its dubious authenticity, the Oath of Agia Lavra is still considered an important aspect of modern Greek mythos.

[2] Khursid Ahmed Pasha was a very powerful and competent leader in the Ottoman Empire in the years prior to the Greek War of Independence. Khursid was originally born to a Christian family in Modern day Georgia and at a young age he was conscripted to the Janissaries. Due to his skill, he became Mayor of Alexandria, then governor of Ottoman Egypt and was later appointed Serasker of the Ottoman Empire during the Serbian Revolution and for his success he was made Grand Vizier (1812-1815). Khursid Pasha was once again appointed Serasker in 1820, first to defeat Ali Pasha of Ioannina, and then to defeat the Greeks.

Last edited: