Quick question: assuming Germanic peoples never reach Britain, what other people(s) could be suited to replace them? Is a migration from East Europe feasible? Would it just stay Celtic territory?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

World Without West

- Thread starter Concavenator

- Start date

Skallagrim

Banned

Quick question: assuming Germanic peoples never reach Britain, what other people(s) could be suited to replace them? Is a migration from East Europe feasible? Would it just stay Celtic territory?

Considering the migrations we saw in OTL, the distance shouldn't be an insurmountable problem. Groups moving through other peoples' lands before ultimately settling somewhere far away from their point of origin... well, that happened. OTL also proves that for certain Germanic peoples, moving to Britain and gaining a foothold there was easier (or otherwise more attractive) than staying on the mainland and duking it out with other Germanic tribes in a fight over territory. So it's not implausible that a group from Eastern Europe (or anywhere else) could travel through northern Europe, find it difficult to find a place (because the peoples already established there are in a superior position and cannot be displaced), and ultimately end up in Britain. They could even gain a foothold by hiring themselves out as mercenaries or something (as a bit or a parallel to OTL's Germanic settlers in Britain).

The main trick is to decide which people could fill this role, and the key factor is giving them a reason to 'go west'. Displacement was the reason in OTL. If you can have some Eastern European people utterly displaced by another people, and thus forced to either migrate or perish, you have your candidate. Important is to pick a people that is not too powerful and numerically overwhelming, because then they can just defeat some Germanic tribes and carve out a domain on the mainland. At the same time, they must also not be too weak and numericslly insignificant, because then the odds increase of them just being defeated and absorbed by other peoples during their migration.

If you want to give it a fun twist, you could have this people migrate to Britain as mercenary forces initially, and then also end up in Ireland. For the twist, have them overthrow some king or lord in Ireland, and carve out their own state there. After that, the Celts in Great Britain get wary, and most of the Eastern European migrants end up in the Irish state that one of their kinsmen has conquered. celtic great Britain remainsd, but Ireland gets settled (at least to some degree) and governed by a foreign people. (Anyway, that's just a suggestion. Do as you will with all my ravings.

The invaders conquering Ireland and mostly leaving Britain alone is a great idea, and fits the timelines tone well.

This is a great timeline BTW.

What is the Nyamist opinion on the slave trade? Considering that part of the reason for the chaos they were fighting against was slave raiding, they could be abolitionist in nature.

An anti-slavery religion dominating northwest Africa would have a huge impact on the history of the region.

Also, do the Bantu migrations still happen?

This is a great timeline BTW.

What is the Nyamist opinion on the slave trade? Considering that part of the reason for the chaos they were fighting against was slave raiding, they could be abolitionist in nature.

An anti-slavery religion dominating northwest Africa would have a huge impact on the history of the region.

Also, do the Bantu migrations still happen?

@Skallagrim: many thanks, that will be very useful. Now I have this vision of a Slavic Britain... (even better! Finnish Britain!) I'm pretty close to completing the makeup of Europe after the Age of Migration, you'll see it in the next chapters.

@Balaur: indeed, Nyamists have a very dim view of the slave trade. This is also part of their general distaste for large scale, long-range trade; however, they aren't opposed to local trade, like city markets and such. Because of that, they are mostly fine with some forms of slavery, for example as a way to pay debts or for prisoners of war: what they can't stand is large numbers of people being rounded up for the purpose of selling them. And then most slaves would be used as household servants.

Of course, they are about as hypocritical as any other human being, so they still allow access to foreign merchants (mostly Celts) in a few harbors on the Atlantic coast (think the southern ports during the isolation of Japan). There could be local populations of non-Nyamist people employed to deal with the merchants, like Jewish moneylenders in medieval Europe. That's a perfect recipe to get a hated minority, I suppose.

As dor the Bantu migrations, most of them occurred before the PoD, and while the most recent ones are in the future, it will take a while yet for the butterflies to reach southern Africa, so for now I'd say they all do.

@Balaur: indeed, Nyamists have a very dim view of the slave trade. This is also part of their general distaste for large scale, long-range trade; however, they aren't opposed to local trade, like city markets and such. Because of that, they are mostly fine with some forms of slavery, for example as a way to pay debts or for prisoners of war: what they can't stand is large numbers of people being rounded up for the purpose of selling them. And then most slaves would be used as household servants.

Of course, they are about as hypocritical as any other human being, so they still allow access to foreign merchants (mostly Celts) in a few harbors on the Atlantic coast (think the southern ports during the isolation of Japan). There could be local populations of non-Nyamist people employed to deal with the merchants, like Jewish moneylenders in medieval Europe. That's a perfect recipe to get a hated minority, I suppose.

As dor the Bantu migrations, most of them occurred before the PoD, and while the most recent ones are in the future, it will take a while yet for the butterflies to reach southern Africa, so for now I'd say they all do.

I'm having some difficulties with the developments in Korea. Back in Chapter 11 I had Gojoseon break down in the Three Kingdoms, but I realize now that it was a century too early even ignoring the butterflies... Anyone have any advice on that?

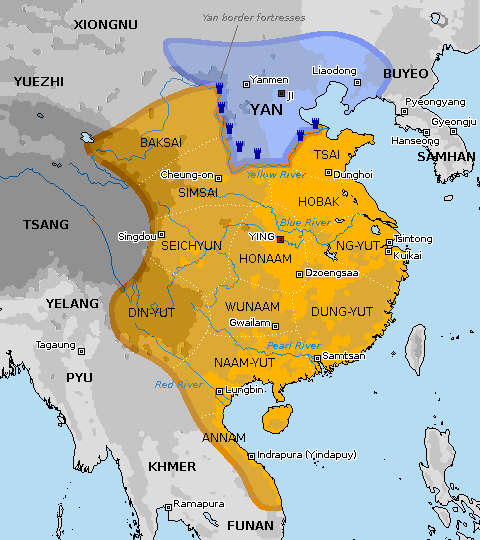

In the meantime, as I work on the next chapter, enjoy this map of the Chu Empire at its greatest extent:

To make things clearer, here's the Mandarin name of cities and provinces:

Baksai = Beixi

Din-yut = Dianyue

Dung-yut = Dongyue

Hobak = Hebei

Honaam = Henan

Naam-yut = Nanyue

Ng-yut = Wuyue

Seichyun = Sichuan

Simsai = Shaanxi

Tsai = Qi

Wunaam = Hunan

Cheung-on = Chang'an (Xi'an)

Dunghoi = Donghai

Dzoengsaa = Changsha

Gwailam = Guilin

Kuikai = Kuaiji (Shaoxing)

Lungbin = Longbien (Hanoi)

Samtsang = Shenzhen

Singdou = Chengdu

Tsintong = Qiantang (Hangzhou)

Ying = Ying

In the meantime, as I work on the next chapter, enjoy this map of the Chu Empire at its greatest extent:

To make things clearer, here's the Mandarin name of cities and provinces:

Baksai = Beixi

Din-yut = Dianyue

Dung-yut = Dongyue

Hobak = Hebei

Honaam = Henan

Naam-yut = Nanyue

Ng-yut = Wuyue

Seichyun = Sichuan

Simsai = Shaanxi

Tsai = Qi

Wunaam = Hunan

Cheung-on = Chang'an (Xi'an)

Dunghoi = Donghai

Dzoengsaa = Changsha

Gwailam = Guilin

Kuikai = Kuaiji (Shaoxing)

Lungbin = Longbien (Hanoi)

Samtsang = Shenzhen

Singdou = Chengdu

Tsintong = Qiantang (Hangzhou)

Ying = Ying

Last edited:

Really pretty map, but I'll point out that the Chu's language would have sounded more like Hubeinese and not Cantonese...Hubeinese being something I'm sure no one on this board speaks, and is much, much harder to find info for. So I guess it's fine.In the meantime, as I work on the next chapter, enjoy this map of the Chu Empire at its greatest extent:

Samstan would also have been named Pun yu (Pun jyu in Cantonese), capital of Nanyue

Last edited:

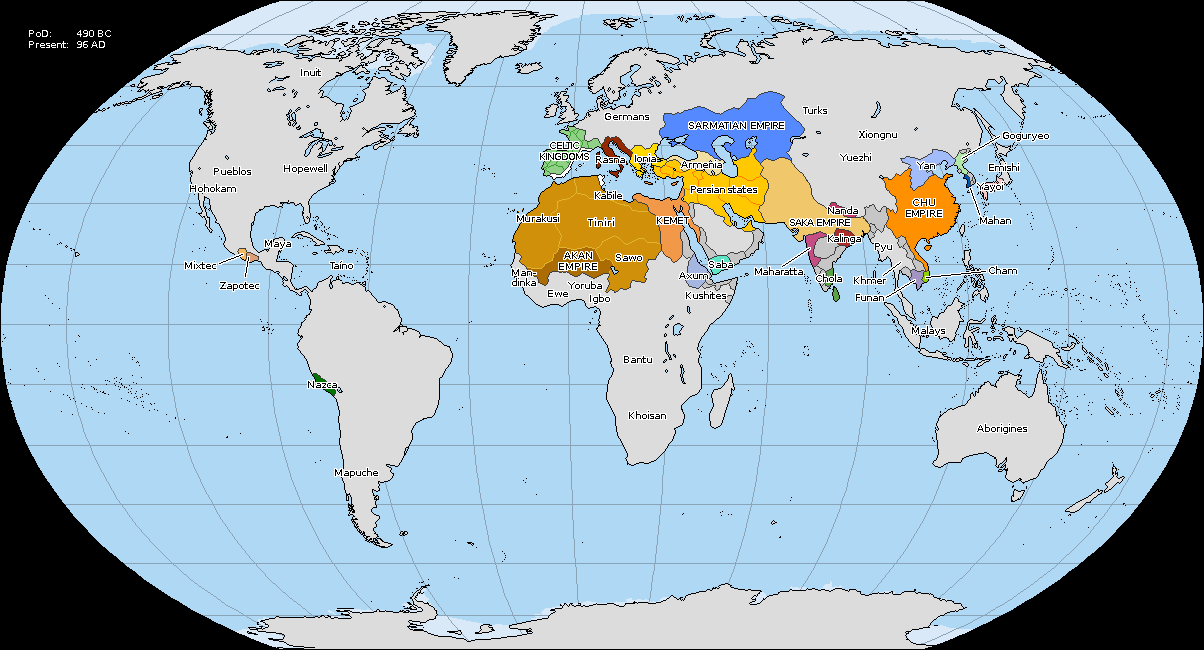

The world in 96 AD, or 230 AS, at Artadeva's death. This corresponds very roughly with the maximum extent of the Saka, Chu, Akan and Sarmatian empires.

Also, retcon in chapter 11. What used to be: "The war was interrupted by troubles in the far north. In Goryeo, Gojoseon had long since fractured into warring kingdoms much like the Zhou before them – chiefly, Goguryeo in the north, Silla in the southeast and Baekje in the southwest. Now this war was turning in favor of Baekje after the fall of Qi had deprived Goguryeo of a staunch ally. In 5 AS [129 BC], with Yan's support, Baekje seized Pyeongyang and pushed north, deep into Goguryeo territory. As frequent Baekje raids threatened Qi coasts, the Chu Empire had to withdraw ships from the Yue Sea and redeploy them in the north."

Now reads: "The war was interrupted by troubles in the far north. In Goryeo, Gojoseon had fractured into warring kingdoms much like the Zhou before them: the largest ones were Goguryeo, highly centralized and militarized, in the north and the elective confederation of Mahan in the southwest. Now the situation was turning in favor of Mahan since the fall of Qi had deprived Goguryeo of a staunch ally, leaving it vulnerable to encroaching from Yan. In 5 AS [129 AS], with Yan support, Mahan seized Pyeongyang and pushed north, deep in Goguryeo territory. As frequent Mahan raids threatened Qi coasts, the Chu Empire had to withdraw ships from the Yue Sea and redeploy them in the north."

(That said, Korean history is still largely a mystery to me, and I'd very much welcome any suggestion or advice in the matter)

Also, retcon in chapter 11. What used to be: "The war was interrupted by troubles in the far north. In Goryeo, Gojoseon had long since fractured into warring kingdoms much like the Zhou before them – chiefly, Goguryeo in the north, Silla in the southeast and Baekje in the southwest. Now this war was turning in favor of Baekje after the fall of Qi had deprived Goguryeo of a staunch ally. In 5 AS [129 BC], with Yan's support, Baekje seized Pyeongyang and pushed north, deep into Goguryeo territory. As frequent Baekje raids threatened Qi coasts, the Chu Empire had to withdraw ships from the Yue Sea and redeploy them in the north."

Now reads: "The war was interrupted by troubles in the far north. In Goryeo, Gojoseon had fractured into warring kingdoms much like the Zhou before them: the largest ones were Goguryeo, highly centralized and militarized, in the north and the elective confederation of Mahan in the southwest. Now the situation was turning in favor of Mahan since the fall of Qi had deprived Goguryeo of a staunch ally, leaving it vulnerable to encroaching from Yan. In 5 AS [129 AS], with Yan support, Mahan seized Pyeongyang and pushed north, deep in Goguryeo territory. As frequent Mahan raids threatened Qi coasts, the Chu Empire had to withdraw ships from the Yue Sea and redeploy them in the north."

(That said, Korean history is still largely a mystery to me, and I'd very much welcome any suggestion or advice in the matter)

15. Ten Thousand Sorrows (274 – 530 AS)

As grand and long-lived as the Chu empire had been, it wasn't meant to last forever. With the frontier of the Yellow River well defended, the Nanda Empire defeated and then destroyed by the Saka invasion, and outposts maintained on every coast of the Yue Sea, at the turn of the 3rd century AS it was larger than ever before. However, corruption and unrest were increasing everywhere. The gwan were not always as virtuous and frugal as Mohist doctrine prescribed, nepotism prevailed in appointing rulers, and many rebellions burst in exasperated villages. Eventually, the army was needed more to keep order within the empire than to secure its borders.

Now the corruption of the Late Chu had its upsides. The lords of this century were great patrons of the arts, as they competed for the magnificence of their courts as Mohist austerity faded away. Palaces were decorated with elaborate mural calligraphy and geometric art, the traditional zithers splintered into a multitude of string instruments with different qualities, and even cuisine became much more refined (the famous honey-glazed carps of Tsintong were probably invented in this time for the local gung).

Hỏa Văn Khiêm (Fo Man Him for the Chu rulers) [1] was born to an impoverished Annamite family around 274 AS [140 AD] in a village near the Red River. He became a bandit on the path to Indrapura, until he was found by imperial officers with a stolen bag of cinnamon in 295 AS [161 AD]. Scheduled for execution, he boasted to the guards about his cunning and his knowledge of the southern lands, impressing the captain Mang enough to be not only released, but appointed a police officer. [2]

Hoa proved himself apt at catching bandits in the Yue regions, and began climbing the military hierarchy; he passed from hunting bandits to squashing rebellions in Nanyue, finally becoming general in 307 AS [173 AD]. He became a common presence in the palace of the gung Kwan Dzoen in Lungbin, and eventually entered in a relationship with his daughter, Kwan Lai. Their story, set on the backdrop of the decaying Chu dynasty, is recounted in Li Angxi's masterpiece Southern Fire (late 8th century); the title is actually wordplay, since the Chinese character for “fire” (fo or huo) is pronounced “hỏa” in Vietnamese.

Hoa's career took a sharp downturn in 313 AS [179 AD], when an excessively aggressive attack against Burmese invaders in Din-Yut [Yunnan] resulted in the loss of a large portion of his army. Because of his connection to Kwan, he couldn't be executed without alienating the gung; instead, he was summoned to Ying by the young emperor Fai. Hoa's personal charm has long been a mystery to historians; other generals and advisers regarded him as boorish and arrogant. He was to be harshly reprimanded, but his boisterous personality fascinated the emperor; he retained his role, and even took one as minor advisor.

But then, in 317 AS [183 AD], Fai died from a fever, leaving only children too young for the throne. Hoa quickly returned to Lungbin, where he had had a son from Kwan Lai, worried for his safety. The regent minister Yim called him back to Ying, possibly to be executed. After long deliberation, Hoa decided to rebel. He did set off for Ying – with a new army he had assembled in the years with Fai's blessing. The march northward was slow and grueling, hindered by the forces loyal to minister Yim.

As if it were a signal from heaven, in 320 AS [186 AD] the skies turned red and ash fell from the sky, brought by the southern wind. Days became darker and colder, a year's worth of crops would be lost. Today we ca assign the responsibility for this to the eruption of the Kagutsuchi caldera in Shin-Nihon [New Zealand] [3], though for the people of China it might have been the signal that the Chu dynasty had finally lost the Mandate of Heaven. Many popular rebellions erupted in the south and spread northwards; if it hadn't been for them, maybe Hoa's army would have been defeated.

The rebel army turned increasingly to guerrilla tactics; Yim tried to prevent the population from helping the rebels by rounding up the inhabitants of towns on their path and deporting them in nearby valleys, or executing whole villages suspected of collaboration. Hoa was blamed for the emperor's death, and captured rebel officers were subjected to gruesome public execution. Getting close to the capital, Hoa besieged the loyalist stronghold of Dzoengsaa [Changsha], which resulted in the death by starvation and disease of almost all inhabitants. Fields were burned, villages razed or depopulated; we'll probably never know how many people died in Hoa's revolt, but they can't have been much fewer than a quarter of the whole Chinese population.

In 323 AS [189 AD], Hoa finally entered Ying. Minister Yim fled the city to Cheung'on [Chang'an]; Fai's son, by now about 12 years old, was found in the gynaeceum; and quickly seized and castrated, to remain there as a eunuch. Hoa set himself up as emperor, and the child he had had from Kwan Lai would be heir to the throne. Kwan Dzoen, who had explicitly backed Hoa only in the latter years of the revolt, was tasked with the pacification of the rebel peasants in the south. Soon the new imperial family would move the court to the more familiar Lungbin, to better control this process. After nearly half a millennium, the Chu dynasty was over; the Huo dynasty had begun.

It took long decades to Hoa Van Khiem, his descendants and their collaborators (the Hoa family was rather quickly assimilated in the Kwan) to restore order to the lands south of the Blue River. There was a significant northwards movement of people, especially with the depopulation of the mid latitudes; Annamite traditions followed them, such as the preparation of fermented fish sauces (which was quickly adapted to the Blue River aquaculture) and ca trù religious singing (go tsau). Under the Huo, the southernization of China reached its peak. Disruption of trade with the southwest pushed Hindu traders to attempt new routes to Goryeo and Nihon.

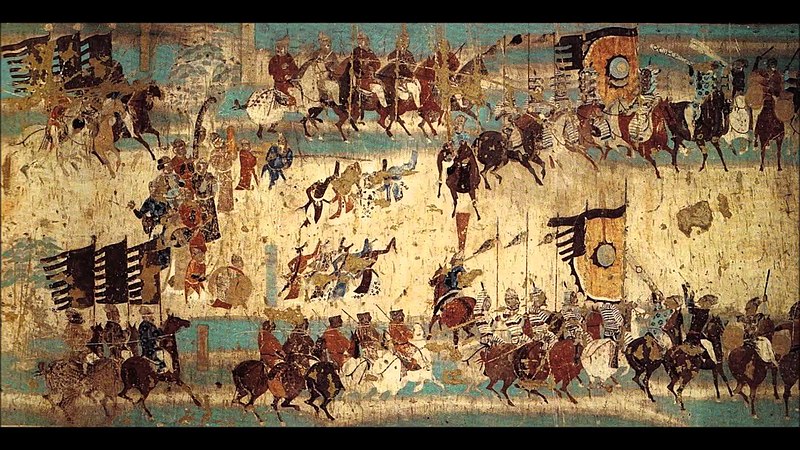

This depiction of the Liang horde is based on artwork posterior to the event by centuries, and may not be completely accurate.

Then things took a turn for the worse. People known in later Chinese histories as the Liang (the “shining”) appeared in the far northwest. Their origins are poorly known; they are first mentioned in 2nd century histories as horse and cattle breeders. They were probably a group of Turkic tribes that lived just beyond the borders, and had often been employed as mercenaries to deal with barbarians further away. The payment for their services was traditionally a task for the gung of Cheung'on – a position that had been left vacant since Yim had taken over the city.

It's still not clear to what point the Liang incursion was a migration of people or a military invasion; large numbers of women and children were reported to settle near the attacked cities. The Kagutsuchi eruption would, after all, leave pastures less productive for many years. They had tried buying grain from China, but trade in the north still suffered, and all food was prohibitively expensive. The Yan kingdom largely managed to deflect them: the fortresses beyond the southward tract of the Yellow River proved themselves effective enough.

The Liang didn't have a single leader, but a number of chiefs that met yearly in a ceremonial horse-skin tent to coordinate their strategies. One of them, known to the Yan as Anjue, pushed southwest to Singdou [Chengdu], in the Seichyun [Sichuan] basin. The siege lasted six months before the city governor delivered himself to the Liang in exchange for the city to be spared. Anjue accepted the deal, and nobody was killed except for the governor and the gung of Seichyun. Other chiefs, however, weren't so accommodating, and the Liang march to the Qi region resulted in millions of casualties.

The Liang people left civilian settlements wherever they went; often, killing the Chinese population was simply a mean to open living space. Cities such as Hepang (“beside the river”) or Yeshi (from a Turkic word for “green”) were founded then; however, most of the Liang lived in the countryside. The Huo dynasty, of course, tried to fight off the invasion; but the diminished and underfunded army was even less effective when directed from the far south. In 358 AS [224 CE] the emperor Tong signed a treaty in Singdou that acknowledged Liang rule in Seichyun and the north. After that, it didn't take long for the chief Yuai to sit in that city as a ruler barely distinguishable from the emperor in Lungbin.

The Liang never really managed to replace the Chinese; at any given time, Turkic people never made up more than a fourth of the population on their territory (except immediately after the plague of 365 AS [231 CE], to which the Chinese were disproportionately susceptible, possibly because carried by parasites of horses). The two peoples interacted quite rarely, though Chinese women were often given in marriage to Liang officers in a rather weak attempt at integration.

Several provinces had broken off from Huo territory. The next centuries will see the empire losing and regaining ever different parts, never achieving again the unity and expansion it had under the late Chu. This unfortunate century is remembered in Chinese history as the Man Beisoeng, the “Ten Thousand Sorrows”; in art it has left behind haunting poetry of lamentation; in history, layers of ruins and countless bones.

[1] Huǒ Wén Qiān in Mandarin. I apologize for the confusion between languages.

[2] Hoa's story is loosely based on OTL Turkic-born general An Lushan, whose rebellion devastated Tang China in the 8th century AD.

[3] As IOTL (though the caldera is known as Taupo; Kagutsuchi is a Japanese deity of fire and volcanoes).

In the next installment: we venture further east.

As grand and long-lived as the Chu empire had been, it wasn't meant to last forever. With the frontier of the Yellow River well defended, the Nanda Empire defeated and then destroyed by the Saka invasion, and outposts maintained on every coast of the Yue Sea, at the turn of the 3rd century AS it was larger than ever before. However, corruption and unrest were increasing everywhere. The gwan were not always as virtuous and frugal as Mohist doctrine prescribed, nepotism prevailed in appointing rulers, and many rebellions burst in exasperated villages. Eventually, the army was needed more to keep order within the empire than to secure its borders.

Now the corruption of the Late Chu had its upsides. The lords of this century were great patrons of the arts, as they competed for the magnificence of their courts as Mohist austerity faded away. Palaces were decorated with elaborate mural calligraphy and geometric art, the traditional zithers splintered into a multitude of string instruments with different qualities, and even cuisine became much more refined (the famous honey-glazed carps of Tsintong were probably invented in this time for the local gung).

Hỏa Văn Khiêm (Fo Man Him for the Chu rulers) [1] was born to an impoverished Annamite family around 274 AS [140 AD] in a village near the Red River. He became a bandit on the path to Indrapura, until he was found by imperial officers with a stolen bag of cinnamon in 295 AS [161 AD]. Scheduled for execution, he boasted to the guards about his cunning and his knowledge of the southern lands, impressing the captain Mang enough to be not only released, but appointed a police officer. [2]

Hoa proved himself apt at catching bandits in the Yue regions, and began climbing the military hierarchy; he passed from hunting bandits to squashing rebellions in Nanyue, finally becoming general in 307 AS [173 AD]. He became a common presence in the palace of the gung Kwan Dzoen in Lungbin, and eventually entered in a relationship with his daughter, Kwan Lai. Their story, set on the backdrop of the decaying Chu dynasty, is recounted in Li Angxi's masterpiece Southern Fire (late 8th century); the title is actually wordplay, since the Chinese character for “fire” (fo or huo) is pronounced “hỏa” in Vietnamese.

Hoa's career took a sharp downturn in 313 AS [179 AD], when an excessively aggressive attack against Burmese invaders in Din-Yut [Yunnan] resulted in the loss of a large portion of his army. Because of his connection to Kwan, he couldn't be executed without alienating the gung; instead, he was summoned to Ying by the young emperor Fai. Hoa's personal charm has long been a mystery to historians; other generals and advisers regarded him as boorish and arrogant. He was to be harshly reprimanded, but his boisterous personality fascinated the emperor; he retained his role, and even took one as minor advisor.

But then, in 317 AS [183 AD], Fai died from a fever, leaving only children too young for the throne. Hoa quickly returned to Lungbin, where he had had a son from Kwan Lai, worried for his safety. The regent minister Yim called him back to Ying, possibly to be executed. After long deliberation, Hoa decided to rebel. He did set off for Ying – with a new army he had assembled in the years with Fai's blessing. The march northward was slow and grueling, hindered by the forces loyal to minister Yim.

As if it were a signal from heaven, in 320 AS [186 AD] the skies turned red and ash fell from the sky, brought by the southern wind. Days became darker and colder, a year's worth of crops would be lost. Today we ca assign the responsibility for this to the eruption of the Kagutsuchi caldera in Shin-Nihon [New Zealand] [3], though for the people of China it might have been the signal that the Chu dynasty had finally lost the Mandate of Heaven. Many popular rebellions erupted in the south and spread northwards; if it hadn't been for them, maybe Hoa's army would have been defeated.

The rebel army turned increasingly to guerrilla tactics; Yim tried to prevent the population from helping the rebels by rounding up the inhabitants of towns on their path and deporting them in nearby valleys, or executing whole villages suspected of collaboration. Hoa was blamed for the emperor's death, and captured rebel officers were subjected to gruesome public execution. Getting close to the capital, Hoa besieged the loyalist stronghold of Dzoengsaa [Changsha], which resulted in the death by starvation and disease of almost all inhabitants. Fields were burned, villages razed or depopulated; we'll probably never know how many people died in Hoa's revolt, but they can't have been much fewer than a quarter of the whole Chinese population.

In 323 AS [189 AD], Hoa finally entered Ying. Minister Yim fled the city to Cheung'on [Chang'an]; Fai's son, by now about 12 years old, was found in the gynaeceum; and quickly seized and castrated, to remain there as a eunuch. Hoa set himself up as emperor, and the child he had had from Kwan Lai would be heir to the throne. Kwan Dzoen, who had explicitly backed Hoa only in the latter years of the revolt, was tasked with the pacification of the rebel peasants in the south. Soon the new imperial family would move the court to the more familiar Lungbin, to better control this process. After nearly half a millennium, the Chu dynasty was over; the Huo dynasty had begun.

It took long decades to Hoa Van Khiem, his descendants and their collaborators (the Hoa family was rather quickly assimilated in the Kwan) to restore order to the lands south of the Blue River. There was a significant northwards movement of people, especially with the depopulation of the mid latitudes; Annamite traditions followed them, such as the preparation of fermented fish sauces (which was quickly adapted to the Blue River aquaculture) and ca trù religious singing (go tsau). Under the Huo, the southernization of China reached its peak. Disruption of trade with the southwest pushed Hindu traders to attempt new routes to Goryeo and Nihon.

This depiction of the Liang horde is based on artwork posterior to the event by centuries, and may not be completely accurate.

Then things took a turn for the worse. People known in later Chinese histories as the Liang (the “shining”) appeared in the far northwest. Their origins are poorly known; they are first mentioned in 2nd century histories as horse and cattle breeders. They were probably a group of Turkic tribes that lived just beyond the borders, and had often been employed as mercenaries to deal with barbarians further away. The payment for their services was traditionally a task for the gung of Cheung'on – a position that had been left vacant since Yim had taken over the city.

It's still not clear to what point the Liang incursion was a migration of people or a military invasion; large numbers of women and children were reported to settle near the attacked cities. The Kagutsuchi eruption would, after all, leave pastures less productive for many years. They had tried buying grain from China, but trade in the north still suffered, and all food was prohibitively expensive. The Yan kingdom largely managed to deflect them: the fortresses beyond the southward tract of the Yellow River proved themselves effective enough.

The Liang didn't have a single leader, but a number of chiefs that met yearly in a ceremonial horse-skin tent to coordinate their strategies. One of them, known to the Yan as Anjue, pushed southwest to Singdou [Chengdu], in the Seichyun [Sichuan] basin. The siege lasted six months before the city governor delivered himself to the Liang in exchange for the city to be spared. Anjue accepted the deal, and nobody was killed except for the governor and the gung of Seichyun. Other chiefs, however, weren't so accommodating, and the Liang march to the Qi region resulted in millions of casualties.

The Liang people left civilian settlements wherever they went; often, killing the Chinese population was simply a mean to open living space. Cities such as Hepang (“beside the river”) or Yeshi (from a Turkic word for “green”) were founded then; however, most of the Liang lived in the countryside. The Huo dynasty, of course, tried to fight off the invasion; but the diminished and underfunded army was even less effective when directed from the far south. In 358 AS [224 CE] the emperor Tong signed a treaty in Singdou that acknowledged Liang rule in Seichyun and the north. After that, it didn't take long for the chief Yuai to sit in that city as a ruler barely distinguishable from the emperor in Lungbin.

The Liang never really managed to replace the Chinese; at any given time, Turkic people never made up more than a fourth of the population on their territory (except immediately after the plague of 365 AS [231 CE], to which the Chinese were disproportionately susceptible, possibly because carried by parasites of horses). The two peoples interacted quite rarely, though Chinese women were often given in marriage to Liang officers in a rather weak attempt at integration.

Several provinces had broken off from Huo territory. The next centuries will see the empire losing and regaining ever different parts, never achieving again the unity and expansion it had under the late Chu. This unfortunate century is remembered in Chinese history as the Man Beisoeng, the “Ten Thousand Sorrows”; in art it has left behind haunting poetry of lamentation; in history, layers of ruins and countless bones.

[1] Huǒ Wén Qiān in Mandarin. I apologize for the confusion between languages.

[2] Hoa's story is loosely based on OTL Turkic-born general An Lushan, whose rebellion devastated Tang China in the 8th century AD.

[3] As IOTL (though the caldera is known as Taupo; Kagutsuchi is a Japanese deity of fire and volcanoes).

In the next installment: we venture further east.

Last edited:

So Japanese colonization of New Zealand?

This looks like an ever harsher version of thr "barbarian" migrations in the late Roman Empire. But it seems they will have no lasting effect compared to the mass Mediterranean migrations. Or will they?

This looks like an ever harsher version of thr "barbarian" migrations in the late Roman Empire. But it seems they will have no lasting effect compared to the mass Mediterranean migrations. Or will they?

This looks like an ever harsher version of thr "barbarian" migrations in the late Roman Empire. But it seems they will have no lasting effect compared to the mass Mediterranean migrations. Or will they?

Oh, this is just the beginning.

The Eurasian empires are past their prime - some are already decaying, which will encourage peoples on the fringes to encroach on their territory. Plus, the classical warm period is ending; the colder climate will bring hunger, disease and migrations, which will exacerbate the former two. As for the specific impact of the Liang, it's early to tell, but the balance of Eurasia is going to change drastically. Africa, too, will start to be affected even south of the Sahara.

whats your plans for scandinavia?

A combination of Celtic influence and Volkswanderung - it will be covered a few chapters from here.

and how diffrent is music and art going to be in this world.

I don't really know much about the history of art outside of Europe (as always, all help and advice is appreciated), but certainly pretty different. Since Mohism frowns on opulence, Chinese visual art is rather subdued, largely focusing on geometrical patterns and calligraphy. The Nyamist tradition instead favors colourful and well-detailed pictures: as the Nyamist doctrine doesn't allow writing down directly the teachings of the Sarmuhene, missionaries go around it by making books entirely out of pictures, a sort of Poor Man's Bible - think of it as a reverse Islam in that regard. The Saka Empire likes monumental statues, while the Celts prefer jewelry or other artwork that you can carry on yourself. Less sure about music; it will probably dominated by the pentatonic scale, since the heptatonic one seems to have appeared much fewer times IOTL.

for music you could probably make heptatonic and other uncommon scales become the common scales, which could lead to an interesting music world and are there any instrument in Europe that not in there in otl and make church hymens and Gregorian chants not popular since they lead to the creation of modern music and make Persian music keep evolving and mix with African music to make it non western.

Interesting... it goes without saying that Christian music is not going to exist. Maybe migrations could carry in Europe music from Central Asia (Tuvan throat singing, anyone?), but TTL religious landscape would definitely be fortunate for Persian and West African music. From a quick search, I'd say harps, setar and other lute-like things for the Persian side, and zithers, balafon (a sort of xylophone made out of gourds) and other percussions for the African one (Nigerian talking drums are awesome)

... So, the Migration Age is coming... does anybody have a people they would like to see expand? The Eurasian steppe, the Caucasus-Persia region, and possibly West Africa and the Horn should be the main sources.

@altwere: many thanks!

@altwere: many thanks!

... So, the Migration Age is coming... does anybody have a people they would like to see expand? The Eurasian steppe, the Caucasus-Persia region, and possibly West Africa and the Horn should be the main sources.

@altwere: many thanks!

I'd be interested in a less widespread but more unified Slavic people.

I could picture them forming an empire centered around modern Poland in a similar fashion to the early Kingdom of Hungary IOTL.

16. The White Bear (ca. 300 – 600 AS)

If the centuries after the apogees of power under Agyenim, Artadeva and the Late Chu mostly see a deterioration and fragmentation of empires, the reverse process was occurring on the islands east of China. By this time, the Four Islands of Nihon were divided in dozens of warring kingdoms. Each of them was centered on a fortified city (almost always on water, fish still being the stock of their diet) surrounded by tributary villages and ruled by a king or queen [1] that also served as priest. Pig breeding was spreading, and the swine were very prized plunder in war.

We don't have direct historical testimonies of this age, as writing didn't yet exist in Nihon; we have to rely on archaeology and on histories written by Chinese and Korean scholars. We know that rice, soy and millet were cultivated, and that sporadic contacts with China and Goryeo occurred, possibly introducing Chu writing in the islands. As the former Chu empire was devastated by rebellion and invasions, many civil servants sought shelter in Nihon, selling their skills and knowledge to one or another kingdom.

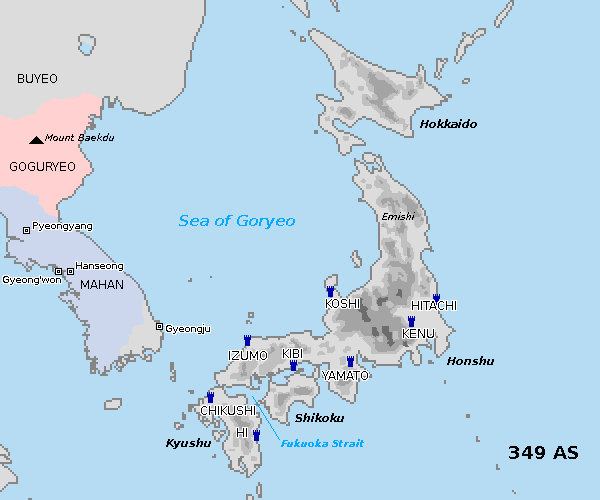

The most powerful polities in Nihon were located in the southern reaches of Honshu (Kibi, Izumo, Kenu) or on Kyushu (Hi, Chikushi). However, we also find Hitachi farther north on Honshu's eastern coast [2]. The southern centers were more influenced by the continent, while Hitachi retained cultural elements from the northern Emishi people, such as the worship of bears (kuma-kami).

The reasons for the rise of Hitachi are debated. It’s often pointed out that a kingdom in southern Honshu could never have held large territories for long, since it would be exposed to attack from all directions, while Hitachi had its back to the ocean and could point all of its resources forward.

For countless centuries, the Nihonese people had lived on hunting, gathering and fishing in extremely abundant waters; now the introduction of agriculture had allowed the southern kingdoms to grow in the scattered plains and basins. Population had almost doubled in size over the last two centuries, and now it rested just below the carrying capacity of the islands. Hitachi, on the other hand, was located in a colder, rockier region where rice had never grown in large amounts. People here were considered barbarous by their southern neighbors: they lived in reed huts, wrapped their food in leaves, and men sported bushy beards.

Curiously, this apparent defect could have been their greatest asset. Presumably, the Kagutsuchi eruption of 320 AS hit cruelly Nihonese agriculture, while it had a much milder effect on fishing. There’s evidence of unrest and raiding; trees felled in this period bear traces of stunted growth, and the bones of a whole generation show signs of malnutrition. The sudden change of weather also raised religious issues.

Okazaki, the half-mythical queen of Hitachi, ordered a thousand sacrifices to restore warmth. This was a modification of the ancient hitobashira custom, in which people were buried alive under important buildings to ensure their stability, apparently now applied to the nation as a whole.

The apparent effectiveness of the ritual strengthened of the central power under Okazaki and her successors. In the years after Kagutsuchi, her blessing of fishermen, foragers and raiders was considered necessary for successful expeditions, and she took the personal responsibility of allocating food among families. This in turn made the favor of the queen the most disputed resource in Hitachi; noble families even offered to the gods of earth some of their less valuable children.

The disturbance of fish migrations had allowed algae to grow more plentiful, and so in that century a bread-like meal prepared with boiled seaweeds, known as kuroi, became one of the most common food in the Islands. Again, Hitachi fishermen profited from this.

The later fate of Nihon was influenced by events on the mainland. In Goryeo, the Mahan Confederation had grew increasingly powerful and increasingly centralized – not to mention no longer elective, to the point of ruling most of the peninsula out of Pyeongyang under the han [3]. Chinese administrators fleeing the fall of the Chu dynasty were employed, curbing the power of the old aristocracy. Mahan culture was at once militaristic and refined, respected in the region for both gold and iron. Thanks to this Chinese infusion, it was also steeped in Mohist philosophy, all the pacifism of the original teachings long purged.

Over the 4th century AS, the influence of Hitachi grows and spreads westward; as population increased, food gathering required more and more blessings; sacrifices had become so frequent that prisoners had to be taken from nearby kingdoms; purchased at first, then captured in ritualistic wars. The western states increasingly resented Hitachi, but none felt confident enough to mount a war. Then, in 349 AS [215 AD], Han Kyeonggeon offered to coordinate a joint attack against the feared eastern kingdom – perhaps to restore his prestige after a failed campaign against Goguryeo.

Preaching the sanctity of the Islands and the overthrow of the Korean influence, queen Shirokuma rallied the villages around Hitachi to its defense. Those villages had been saved from famine with the fish and kuroi purchased with holy blood, and protected from robberies by her soldiers. A vast army marched west under a banner depicting a white bear. Though the very existence of the army has long been believed a myth – especially by Chinese and Korean scholars – recent discoveries seem to support its existence, including one of the original banners.

Shirokuma's strategy appears to have been appealing to the satellite villages which had lost much of their autonomy with the strengthening of the kingdoms. They feared oppression less from a faraway imperial court than from a nearby royal palace. Her control area grew quickly – especially after the Korean attempt to supply soldiers to Izumo was foiled by a storm in 353 AS [219 AD]. By the end of the decade, Korean influence in Nihon was confined to the coast of Kyushu. Kyeonggeon and his heir focused on bringing this island under their rule, and the later han eventually lost interest in the other ones.

Each of the Nihonese states was ruled by a clan with its own ancestral deity or kami. With the unification under Hitachi underway, these hundreds of deities now had to be incorporated in a coherent belief system, which bore some resemblance to the proto-Daoism of southern China. The empress took the title of “servant of all kami”, which made her a necessary intermediary between the clans and the gods. As she claimed direct divine heritage, her imperial name would go down as Ichihiko, the one daughter of the Sun.

The government of Nihon wasn't established along Chinese lines as that of Mahan. Rather, each clan would keep administrating its own lands while acknowledging political and religious submission to the court of Hitachi. Villages had a right to appeal to the imperial court for injustices. In fact, we don't really know how much direct control the earliest empresses had on Nihon outside the Hitachi province, and the claims of complete supremacy by certain recent historians seem too ideologically motivated to be reliable.

Empress Ichihiko appears for the spring religious ceremonies.

Except for scattered fishermen, there was no significant contact between the mainland and the Island for almost half a century. Our next source on Nihon is Ho Seung'eun, a Mohist philosopher who was sent as envoy to Nihon in 400 AS [266 AD] by Han Bangmun. His impressions are collected in the Saeyugi (“Journey to the East”), which would remain for centuries one of the most popular texts of Korean literature. Leaving from Kyushu, he landed in the harbor of Osaka, and traveled northeast to Hitachi.

He describes a quickly growing population building many new villages in the mountain valleys, sustained mostly by fishing in rivers, but also by kuroi rations carried by a special class of messengers. Buildings were mostly in wood and bamboo, though the largest cities had temples built from massive limestone blocks. Human sacrifices were practiced on these temples every spring, the offers picked through an elaborate system of lotteries and sacred games. Despite this bloody practice, the population was mostly peaceful, if wary of foreigners.

According to Seung'eun, the provinces were administered with great autonomy by the tributary clans, except the regions around major harbors such as Izumo and Osaka, which were controlled more directly by representatives of the empress. There was a caste of scholars whom he met several times, and who studied Chinese and Korean texts. Except for these – both written in the Chinese niu tsung characters [4] – there was no written language in all Nihon.

Over a century later, most of the Korean peninsula had been united under the Mahan. Generations of han ruled there harshly, with the constant threat of the Goguryeo remnant in the north. This still held sacred sites such as Mount Baekdu, leading to great resentment. The far south produced most of the food, in form of rice and fish, and was entrusted to a complex hierarchy of ministers, while the less fertile north was ruled via military governors. A class of slaves, derived from prisoners of war and bankrupt commoners, was employed in great public projects like irrigation channels and paved roads.

The great harbor at Gyeong'won [Incheon] was built in this period, to assist exchanges with China. The new culture that had arose under the Huo rule was fascinating to Korean scholars; silk weaving was introduced, and Annamite spices were exchanged with iron from the northern mines for the pleasure of the royal family. The infusion of Chinese culture had lasted for many generations; but towards the end of the 6th century the ports grew quieter, and Goryeo closed in itself, much like their kin in the east.

Ruins of a temple complex near Osaka.

[1] From what I found, Yayoi era Japan was at least partially matriarchal, with children raised in the mother's household and female rulers until the 8th century AD.

[2] While a city with this name existed (and exists) OTL, Hitachi as described here is largely a product of butterflies. You might see Okazaki as an alternate Queen Himiko.

[3] No relation to the Chinese Han people or state: it's a term for “ruler” of Central Asian origin, cognate of khan.

[4] The “bird and worms” seal script developed in Chu during the Warring States period.

In the next installment: kingdoms rise and fall in the far north.

If the centuries after the apogees of power under Agyenim, Artadeva and the Late Chu mostly see a deterioration and fragmentation of empires, the reverse process was occurring on the islands east of China. By this time, the Four Islands of Nihon were divided in dozens of warring kingdoms. Each of them was centered on a fortified city (almost always on water, fish still being the stock of their diet) surrounded by tributary villages and ruled by a king or queen [1] that also served as priest. Pig breeding was spreading, and the swine were very prized plunder in war.

We don't have direct historical testimonies of this age, as writing didn't yet exist in Nihon; we have to rely on archaeology and on histories written by Chinese and Korean scholars. We know that rice, soy and millet were cultivated, and that sporadic contacts with China and Goryeo occurred, possibly introducing Chu writing in the islands. As the former Chu empire was devastated by rebellion and invasions, many civil servants sought shelter in Nihon, selling their skills and knowledge to one or another kingdom.

The most powerful polities in Nihon were located in the southern reaches of Honshu (Kibi, Izumo, Kenu) or on Kyushu (Hi, Chikushi). However, we also find Hitachi farther north on Honshu's eastern coast [2]. The southern centers were more influenced by the continent, while Hitachi retained cultural elements from the northern Emishi people, such as the worship of bears (kuma-kami).

The reasons for the rise of Hitachi are debated. It’s often pointed out that a kingdom in southern Honshu could never have held large territories for long, since it would be exposed to attack from all directions, while Hitachi had its back to the ocean and could point all of its resources forward.

For countless centuries, the Nihonese people had lived on hunting, gathering and fishing in extremely abundant waters; now the introduction of agriculture had allowed the southern kingdoms to grow in the scattered plains and basins. Population had almost doubled in size over the last two centuries, and now it rested just below the carrying capacity of the islands. Hitachi, on the other hand, was located in a colder, rockier region where rice had never grown in large amounts. People here were considered barbarous by their southern neighbors: they lived in reed huts, wrapped their food in leaves, and men sported bushy beards.

Curiously, this apparent defect could have been their greatest asset. Presumably, the Kagutsuchi eruption of 320 AS hit cruelly Nihonese agriculture, while it had a much milder effect on fishing. There’s evidence of unrest and raiding; trees felled in this period bear traces of stunted growth, and the bones of a whole generation show signs of malnutrition. The sudden change of weather also raised religious issues.

Okazaki, the half-mythical queen of Hitachi, ordered a thousand sacrifices to restore warmth. This was a modification of the ancient hitobashira custom, in which people were buried alive under important buildings to ensure their stability, apparently now applied to the nation as a whole.

The apparent effectiveness of the ritual strengthened of the central power under Okazaki and her successors. In the years after Kagutsuchi, her blessing of fishermen, foragers and raiders was considered necessary for successful expeditions, and she took the personal responsibility of allocating food among families. This in turn made the favor of the queen the most disputed resource in Hitachi; noble families even offered to the gods of earth some of their less valuable children.

The disturbance of fish migrations had allowed algae to grow more plentiful, and so in that century a bread-like meal prepared with boiled seaweeds, known as kuroi, became one of the most common food in the Islands. Again, Hitachi fishermen profited from this.

The later fate of Nihon was influenced by events on the mainland. In Goryeo, the Mahan Confederation had grew increasingly powerful and increasingly centralized – not to mention no longer elective, to the point of ruling most of the peninsula out of Pyeongyang under the han [3]. Chinese administrators fleeing the fall of the Chu dynasty were employed, curbing the power of the old aristocracy. Mahan culture was at once militaristic and refined, respected in the region for both gold and iron. Thanks to this Chinese infusion, it was also steeped in Mohist philosophy, all the pacifism of the original teachings long purged.

Over the 4th century AS, the influence of Hitachi grows and spreads westward; as population increased, food gathering required more and more blessings; sacrifices had become so frequent that prisoners had to be taken from nearby kingdoms; purchased at first, then captured in ritualistic wars. The western states increasingly resented Hitachi, but none felt confident enough to mount a war. Then, in 349 AS [215 AD], Han Kyeonggeon offered to coordinate a joint attack against the feared eastern kingdom – perhaps to restore his prestige after a failed campaign against Goguryeo.

Preaching the sanctity of the Islands and the overthrow of the Korean influence, queen Shirokuma rallied the villages around Hitachi to its defense. Those villages had been saved from famine with the fish and kuroi purchased with holy blood, and protected from robberies by her soldiers. A vast army marched west under a banner depicting a white bear. Though the very existence of the army has long been believed a myth – especially by Chinese and Korean scholars – recent discoveries seem to support its existence, including one of the original banners.

Shirokuma's strategy appears to have been appealing to the satellite villages which had lost much of their autonomy with the strengthening of the kingdoms. They feared oppression less from a faraway imperial court than from a nearby royal palace. Her control area grew quickly – especially after the Korean attempt to supply soldiers to Izumo was foiled by a storm in 353 AS [219 AD]. By the end of the decade, Korean influence in Nihon was confined to the coast of Kyushu. Kyeonggeon and his heir focused on bringing this island under their rule, and the later han eventually lost interest in the other ones.

Each of the Nihonese states was ruled by a clan with its own ancestral deity or kami. With the unification under Hitachi underway, these hundreds of deities now had to be incorporated in a coherent belief system, which bore some resemblance to the proto-Daoism of southern China. The empress took the title of “servant of all kami”, which made her a necessary intermediary between the clans and the gods. As she claimed direct divine heritage, her imperial name would go down as Ichihiko, the one daughter of the Sun.

The government of Nihon wasn't established along Chinese lines as that of Mahan. Rather, each clan would keep administrating its own lands while acknowledging political and religious submission to the court of Hitachi. Villages had a right to appeal to the imperial court for injustices. In fact, we don't really know how much direct control the earliest empresses had on Nihon outside the Hitachi province, and the claims of complete supremacy by certain recent historians seem too ideologically motivated to be reliable.

Empress Ichihiko appears for the spring religious ceremonies.

Except for scattered fishermen, there was no significant contact between the mainland and the Island for almost half a century. Our next source on Nihon is Ho Seung'eun, a Mohist philosopher who was sent as envoy to Nihon in 400 AS [266 AD] by Han Bangmun. His impressions are collected in the Saeyugi (“Journey to the East”), which would remain for centuries one of the most popular texts of Korean literature. Leaving from Kyushu, he landed in the harbor of Osaka, and traveled northeast to Hitachi.

He describes a quickly growing population building many new villages in the mountain valleys, sustained mostly by fishing in rivers, but also by kuroi rations carried by a special class of messengers. Buildings were mostly in wood and bamboo, though the largest cities had temples built from massive limestone blocks. Human sacrifices were practiced on these temples every spring, the offers picked through an elaborate system of lotteries and sacred games. Despite this bloody practice, the population was mostly peaceful, if wary of foreigners.

According to Seung'eun, the provinces were administered with great autonomy by the tributary clans, except the regions around major harbors such as Izumo and Osaka, which were controlled more directly by representatives of the empress. There was a caste of scholars whom he met several times, and who studied Chinese and Korean texts. Except for these – both written in the Chinese niu tsung characters [4] – there was no written language in all Nihon.

Over a century later, most of the Korean peninsula had been united under the Mahan. Generations of han ruled there harshly, with the constant threat of the Goguryeo remnant in the north. This still held sacred sites such as Mount Baekdu, leading to great resentment. The far south produced most of the food, in form of rice and fish, and was entrusted to a complex hierarchy of ministers, while the less fertile north was ruled via military governors. A class of slaves, derived from prisoners of war and bankrupt commoners, was employed in great public projects like irrigation channels and paved roads.

The great harbor at Gyeong'won [Incheon] was built in this period, to assist exchanges with China. The new culture that had arose under the Huo rule was fascinating to Korean scholars; silk weaving was introduced, and Annamite spices were exchanged with iron from the northern mines for the pleasure of the royal family. The infusion of Chinese culture had lasted for many generations; but towards the end of the 6th century the ports grew quieter, and Goryeo closed in itself, much like their kin in the east.

Ruins of a temple complex near Osaka.

[1] From what I found, Yayoi era Japan was at least partially matriarchal, with children raised in the mother's household and female rulers until the 8th century AD.

[2] While a city with this name existed (and exists) OTL, Hitachi as described here is largely a product of butterflies. You might see Okazaki as an alternate Queen Himiko.

[3] No relation to the Chinese Han people or state: it's a term for “ruler” of Central Asian origin, cognate of khan.

[4] The “bird and worms” seal script developed in Chu during the Warring States period.

In the next installment: kingdoms rise and fall in the far north.

Skallagrim

Banned

There was a caste of scholars whom he met several times, and who studied Chinese and Korean texts. Except for these – both written in the Chinese niu tsung characters [4] – there was no written language in all Nihon.

[4] The “bird and worms” seal script developed in Chu during the Warring States period.

Awesome to see the "birds and worms" script get a shout-out. I've always thought it's extremely pretty. Of course, with Chu being a dominant empire, at least for the time being, the script may well get a boost. I'm not sure if it can work out timeframe-wise, but how cool would it be for Japan - or Nihon, rather - to base its own script on the "birds and worms" script, borrowing from China as in OTL, but just in a different way?

(Yes, I'm aware that I picked a really weird detail to focus on. Apologies.)

What was the language spoken by the people of Nihon (I mean south of the Emishi)? Was it related to the language of Mahan?

Share: