It's interesting and unexpected to see Incans coming back as a modern nation. Best of luck for them, they're the only native American nation in the whole of Americas.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Down the Parallel Road: An Afsharid Persia Timeline

- Thread starter Nassirisimo

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 61 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Africa - 1829 to 1862 South and Central America - 1829 to 1862 North America - 1829 to 1862 Eastern Europe - 1829 to 1862 Central Europe - 1829 to 1860 Western Europe - 1829 to 1860 The European Revolutions - 1860 The European Revolutions - 1861The growth of the Philippines in particular in the 20th century is really something. Part of the enormous growth of the "Global South" in the 20th century I would suppose, but I do wonder if that growth would be curbed by a more prosperous Philippines. I suppose what happens depends on how and when the Philippines gets independence and what happens afterward.Around 1900, the Philippines had something in the order of 8 million people. Japan was somewhere in the whereabouts of 60 millions IIRC. (Currently, the Philippines are at around 100M and increasing, Japan in the 120M province and decreasing, in a couple of generations or less the Philippines might overtake Japan in pop. numbers).

Well, those problems are still present in the OTL American South (Columbia) as we will see in the next update. Brazil is (and was in OTL) the only Latin American country with a large population of slaves. Although the Transatlantic Slave Trade has been ended earlier than OTL, that doesn't mean that slavery itself will necessarily be stamped out earlier. Indeed, we could possibly see legal slaveholding in the Western Hemisphere into the 20th century depending on how things go.Interesting to see the race problems that plagued the United States of American in OTL installed in Latin America this time around.

Culturally and politically, this Inca state probably owes more to Europe than to the Incas of old, though self-identification counts for a lot. Although the national costume is colonial-era Spanish in origin, and although they practice small-holding rather than the centrally planned economy of the Incas, there is a very strong identification with the past.Okay, the neo-Incan republic is a nice surprise! And interesting to see how its leaders are basing their rule on European forms of governance, with a parliament and all. Do they augment indigenous forms of rule at the local level? Given the struggles of their independence, I'd wager there would be a aversion to large landholdings and a call to "return" back to old traditions.

And the Mexican government's discrimination of Chinese workers has a lot of potential paths. Do they restrict the laborers from obtaining brides? And are the laborers allowed contact with the native tribes of California?

Oh God, slave farms.Looks like Brazil has taken up the mantle of the OTL American South.

The discriminatory laws against the Chinese are mainly to do with land ownership, which the Chinese are forbidden to do within Mexico. As a result, much of the land is held by absentee warlords. The Chinese population tends toward males in California but as Chinatowns are established in the cities, an increasing number of women are joining their menfolk.

It is likely that Brazil and Columbia will be something of "Partners in Crime" when it comes to slavery, and may be able to resist European pressure for quite some time, especially if nice cheap cash crops such as cotton and coffee keep coming.

While I think only Peru is likely to hold antipathy toward them, the Incas may have a problem when it comes to other anti-Colonial movements on the part of Natives elsewhere in South America and what attitude should be taken toward them.It's interesting and unexpected to see Incans coming back as a modern nation. Best of luck for them, they're the only native American nation in the whole of Americas.

North America - 1829 to 1862

Pierre Moreau; Great Power Politics Revisited: The Economic and Military Power of States 1500-2000

Anglophone North America

Of all areas of the world, it was North America that saw the most immigration by quite some margin in the 19th century. As technologies such as the railway and the steam ship began to make the vast continent more accessible, increasing numbers of people, not all from Europe, went to make their new lives on the continent. Initially, it seemed as though it would be Alleghany that would benefit the most from this immigration. Its population skyrocketed, from around 5.5 million in 1835 to over 8 million by 1860 as people fled from the poverty and repression found in Europe. Many of these new arrivals settled in the rapidly growing cities of the East Coast, particularly Boston, Philadelphia and above all, New York. New York’s population quadrupled in 30 years, a testament to the swift growth of cities in Allegheny, a feat which up to that point had not been emulated anywhere else in North America. The cities of Allegheny were quickly becoming “Shock Cities” of modern industrialism, to a similar extent of Leeds and Manchester across the Atlantic.

Columbia, the erstwhile cousin of Allegheny, tended much less toward the path of urbanization. Her population grew far more slowly, reaching around 6 million by 1860. This was in part due to lower rates of immigration from Europe, who had far less factory jobs and free land to be attracted by, but was also caused by the phenomenon of runaway slaves. Columbia remained the only corner of the North American mainland where slavery was still legal following Mexico’s abolition in 1836, but there appeared to be no lessening of the intensity of the institution. The slave population grew in relation to that of free blacks, especially with the emigration of the latter to Allegheny and increasingly Louisiana. Among the elites in Columbian society, the value of slavery in maintaining appropriate relationship between different races, as well as in ensuring quality of life for slaves was emphasised, though this contrasted to the cruel reality found on most plantations. After the slave trade out of Africa was cut off in the 1820s, the slave trade within Columbia intensified. The growth of the cotton trade in the Deep South in particular led to an internal pattern in which slaves were sold from Virginian farms to the more productive cotton plantations of southern states such as Alabama and Georgia.

The changing dynamics of the slave trade also had their impact on the economy of Columbia. Despite the opposition of many governments in Europe to slavery, there was little pressure on European manufactures to stop importing from the slaveholding south, nor was there much in the way of pressure on Columbia to curb the practice. While the manufacturing based economy of Allegheny did grow in the first half of the 19th century, it could not compare to the massive boom in exports from Columbia, based mainly on cotton. By 1860, Columbia’s exports were worth 50% more than those from Allegheny. Many of the profits from these exports went to the planter class, who as well as building elegant houses on their estates, maintained neoclassical villas in Charleston. Numerous European visitors were greatly impressed by Charleston, and contrasted the elegant buildings, clean streets and general air of prosperity favourably with the squalid conditions in many of Allegheny’s cities. It seemed to be limited to a few liberal activists to point out that the city’s prosperity was based upon the largely invisible human misery inflicted on millions of slaves throughout Columbia.

Both of the Anglophone American states saw economic and population growth in the era, which added to the increased desire for more land to settle, in Allegheny for family-owned homestead farms, and in Columbia for further fertile land for cotton plantations. Aside from occasional border clashes, both states were too scared of the other to consider a war for expansion, and considered the densely populated border areas as unsuitable at any rate. Hungry eyes instead turned westwards to the Mississippi Valley, controlled by France. Both Columbia and Allegheny were aware that intrusion by either of them would mean an unwinnable war with the strongest power in the world. Nevertheless, demands from settlers, as well as politicians who saw the future potential of the Mississippi Valley, put pressure to find some accommodation with France. After the death of King François in 1831, the new French government proved more amenable to selling the east bank of the Mississippi. After two years of negotiations, the three powers agreed on a purchase and fair separation of the land. For the enormous sum of 50 million livres each, both would gain hundreds of thousands of square kilometres of land, as well as access to the east bank of the Mississippi.

* * * * * *

Francophone North America

Francophone North America

After the death of King François, France’s policy toward her North American colonies began to change somewhat. In his last years, even he had become somewhat wary of their developing identities, which came as the population of New France began to skyrocket. Nervous that the process that had taken place in Britain’s colonies would happen to her own, the French implemented various measures, including regional parliaments to keep her colonies loyal to the metropole. However, with British and Alleghanian support of the independence movement, the Quebecois felt confident enough to declare independence in 1836, precipitating a war that would last four years before the French recognised the independence of her erstwhile colony. New France, now renamed the Republic of Quebec, forged close relations with Allegheny and to some extent followed her model. The city of Montreal began to grow, though not quite to the same extent of New York, while the countryside became dominated by small farmers.

In Louisiana however, the circumstances were rather different. Far more sparsely populated than Quebec, the French government saw little use for the colony, and had at one point mooted selling almost all of it to pay off some of the national debt. However, the 1820s saw the growth of the port of New Orleans, as well as increased immigration into Louisiana both from Europeans as well as Free Blacks from elsewhere in the Americas, attracted by the lack of restrictive racial laws. By 1835, the population had exceeded a million, and many of these had been greatly angered by the sale of much of the East Bank of the Mississippi to Allegheny and Columbia. Voices for independence grew louder, but envisioned a different kind of state than any of the existing North American states. More than any others, the founding fathers of independent Louisiana were inspired by “Classical Liberalism”, a pro-Industry ideology that had emerged in the United Kingdom. Rather than a nation of smallholding but poor farmers, or of a slavery-dominated export economy, the founding fathers of Louisiana envisioned free markets that would guarantee an increase in prosperity.

Louisiana proved to be very prosperous indeed after independence. As the Mississippi and Ohio valleys became increasingly populated, it was New Orleans more than any other city in North America that benefitted. The wealth of rapidly growing cities in both the Anglophone and Francophone areas of the Mississippi such as Losantiville and Memphis, as well as the growing agricultural wealth of the Mississippi basin all flowed to the outside world through New Orleans [1]. As a result, the population of the city skyrocketed, to hit around 400,000 by 1860. The increasing prosperity and population of Louisiana however did leave some “Old French” settlers uneasy about the pace of change. In the 1860s, a new religious movement that echoed Christian Revivalism in the Anglophone world and which preached a simpler, less materialistic life, supposedly in the mould of Jesus Christ himself, emerged among French Protestant communities in Louisiana and to a lesser extent, Quebec. These communities eventually settled in the “Great Plains” region of America led by their charismatic leader, Claude Cartier, and numbered some 50,000 in all. Following the “Treaty of the Open Sky” with many of the native peoples of the region such as the Lakota, a government based on mixed white-native sovereignty and cooperation was founded.

This model of cooperation between whites and natives contrasted with the dispossession of the native peoples experience elsewhere in North America. In the Anglophone territories and Louisiana, native peoples continually saw white settlers move into their lands, often acting violently toward the native inhabitants. “Indian Removals” became part and parcel of government policy in both Columbia and Allegheny, though this did not happen without protest among the white populations of both countries. In Mexico, the native peoples fared somewhat better due to the distant nature of Mexico’s central government. Although in coastal Alta California, natives saw themselves dispossessed due to the influx of Chinese labourers, natives in the interior such as the Apache and Comanche peoples enjoyed a measure of autonomy. Indeed, during the period the Comanche people prospered in the absence of white settlement and with various victories over their native American neighbours.

[1] – Losantiville is Cincinnati in OTL. Memphis in this timeline is a French speaking city on the opposite bank of the Missisippi

* * * * * *

Author's Notes - North America's much more fragmented political geography when compared to OTL is starting to show its effects. As Louisiana becomes increasingly more populated, it becomes unlikely that Anglophone settlers will ever be able to push into the "Wild West", which buys the natives of the Far West quite a bit of time. An equally interesting development is a kind of alt-Mormonism (though only in the sense it is a new religious movement) among the small Francophone Protestant communities that appears to be positively accepting of the natives. Although tensions do exist between the Great Plains Indians and the new arrivals, a collective shunning of alcohol and attempts not to infringe on each other could mean that the Great Plains Indians may do somewhat better than OTL. And of course, without much in the way of white settlement of the Northwest Coast, Natives there are doing somewhat better.

Although the split between the North and South, as well as the limitation of its settlement is having a big effect on Anglophone North America, it is nevertheless doing fairly well for itself.

Around 1900, the Philippines had something in the order of 8 million people. Japan was somewhere in the whereabouts of 60 millions IIRC. .

Japan was more like 45 million in 1900: they were still growing fast.

I presume Peru here includes Bolivia? The split between "Inca" and Hispanic Peru might be more northwest/southeast than east/west, since "east" ultimately means the Amazon basin in Peru, and the Tupac Amaru rebellion of OTL was in the south. Or is Hispanic Peru a long thin stringbean of a purely coastal state, with the natives taking back the highlands?

Re the "French Mormons", good relations with the plains Indians depends on them remaining a fairly light presence on the plains. Buffalo tend to keep away from farmed and fenced land: they are capable of plowing right through, but generally they just change their routes, which for Buffalo-dependent tribes can be a severe disruption.

Re the "French Mormons", good relations with the plains Indians depends on them remaining a fairly light presence on the plains. Buffalo tend to keep away from farmed and fenced land: they are capable of plowing right through, but generally they just change their routes, which for Buffalo-dependent tribes can be a severe disruption.

I presume Peru here includes Bolivia? The split between "Inca" and Hispanic Peru might be more northwest/southeast than east/west, since "east" ultimately means the Amazon basin in Peru, and the Tupac Amaru rebellion of OTL was in the south. Or is Hispanic Peru a long thin stringbean of a purely coastal state, with the natives taking back the highlands?

The Aymara are also an important group in Peru, in what is now Bolivia, and they still make up a majority in much of Bolivia such as the land around La Paz. It seems to me that they'll be a major headache in Spanish Peru for the foreseeable future.

And so springs an independent Quebec and an alternate French identity. With a less English-speaking North America, I wonder what forms of popular culture will develop ITTL; French Jazz with English loanwords in New Orleans, maybe?

Could it have been the higher figure if the very-happy-to-be-in-the-empire peoples of Korea and Taiwan were included as part of the total?Japan was more like 45 million in 1900: they were still growing fast.

Correct. No Simon Bolivar so... yeah. I'd envisioned this revolt largely as inspired by the revolt of Tupac Amaru, and indeed the first map you drew up actually corresponds fairly closely to the territory I had in mind for the Inca, with the exception that Hispanic Peru is slightly bigger than it is in yours. As far as I'm aware (and the demographics of Peru aren't my strong suit) pretty much whole of the interior of Peru and Bolivia at this point would have been majority native at this point right?I presume Peru here includes Bolivia? The split between "Inca" and Hispanic Peru might be more northwest/southeast than east/west, since "east" ultimately means the Amazon basin in Peru, and the Tupac Amaru rebellion of OTL was in the south. Or is Hispanic Peru a long thin stringbean of a purely coastal state, with the natives taking back the highlands?

View attachment 336373

Re the "French Mormons", good relations with the plains Indians depends on them remaining a fairly light presence on the plains. Buffalo tend to keep away from farmed and fenced land: they are capable of plowing right through, but generally they just change their routes, which for Buffalo-dependent tribes can be a severe disruption.

As long as the population of these French settlers on the plains remains relatively low, there shouldn't be too much of a problem. However, if OTL showed us one thing, it's that the white man just cannot resist huge amounts of sparsely populated and very fertile agricultural land.

I think to some extent it all depends on what foreign policy stance is taken by the neo-Inca. On one hand, they could attempt to isolate themselves and not provoke a reaction against them, but on the other hand they could see an interest in creating some neighbouring native ruled friendly states.The Aymara are also an important group in Peru, in what is now Bolivia, and they still make up a majority in much of Bolivia such as the land around La Paz. It seems to me that they'll be a major headache in Spanish Peru for the foreseeable future.

Louisiana will if anything be even more African influenced than OTL, so the mingling of French, African-American and Caribbean Creole influences could certainly make for some interesting cultural developments once popular culture really gets going later on in the century! I think culturally as well as in other respects, New Orleans is going to be a giant of a city in TTL.And so springs an independent Quebec and an alternate French identity. With a less English-speaking North America, I wonder what forms of popular culture will develop ITTL; French Jazz with English loanwords in New Orleans, maybe?

Eastern Europe - 1829 to 1862

Theodoros Marinou; The Mountainous Periphery: A History of Southeastern Europe

The Consolidation of the Modern Balkans

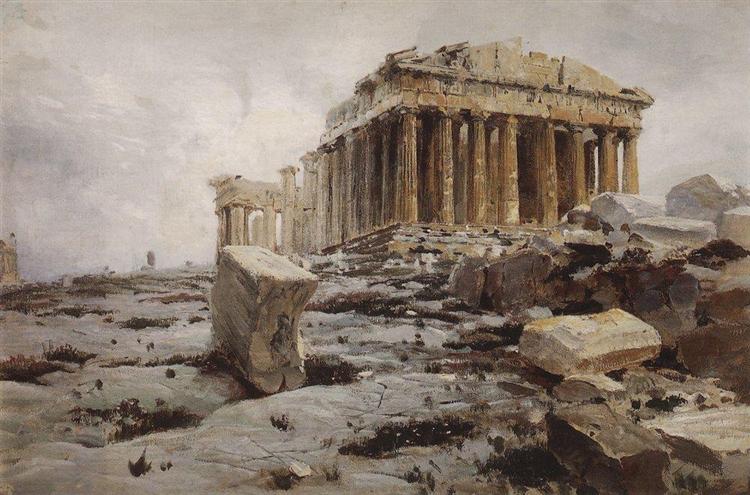

Upon winning their independence from the Ottoman Empire, the Balkan Kingdoms of Serbia, Montenegro, Greece and Bulgaria were seen as nothing more than “Bandit Kingdoms”, to use the phrase of the British King William. Although their former Turkish rulers were not seen in any more positive of a light, the Balkan nations were viewed as backward, with almost none of the amenities found in “Civilized Europe”. While the British and French sneered at the new nations, both the Russians and Austrians attempted to wield influence in these new nations. Indeed, it was largely Russian actions that had secured the independence of the Balkan states with their war against Turkey. Due to this, as well as the sympathy generated by their common Orthodox faith (and Slavic ethnicity in the cases of Serbia, Montenegro and Bulgaria), Russia was seen by many to be the dominant ideological influence in the new states. However, most of the new countries were landlocked, sharing borders only with the hostile Turks as well as Austria. No matter what vague feelings of brotherhood remained toward the Russians, for Serbia and Bulgaria it became paramount to maintain good relations with Austria, who was the primary trading partner of each country.

Greece however, even at this early point appeared to be diverging somewhat with the other two larger Balkan countries. Unlike Serbia and Bulgaria, she was dominated by her long coastline, which endowed her with a more maritime-focused identity. Utilising her connections with large Greek communities that remained under Ottoman rule, Greece steadily began to build up a comparatively large merchant marine, making up for in trade what she lacked in agricultural potential. However, Greece was also hobbled by the stronger regional interests, who strongly resented the imposition of a centralised state upon them. The first king of Greece, Andreas Pierrakos, lasted a mere four years on the throne before he was unseated by a coalition of warlords from the Morea, who placed his young son Ioannis on the throne. For ten years, Greece was dominated by regional warlords and chieftains, who had been the chief force in driving out the Ottomans but who were now also beginning to seriously harm Greece themselves as the countryside fell to disorder. Once Ioannis came to the throne, it was hoped that he could be safely dominated, but the young king had a mind of his own.

Properly securing the tax base of Attica, and more importantly, some income from the many merchants based in Athens, Ioannis began building up his own personal guard. With their distinctive Fustanella uniforms, the size of the guard was built up into the most significant armed force in Greece. This would be the core of the Royalist army in the Greek Civil War of 1844-47. During this fierce conflict between the king and Greece’s powerful regional rulers, much of Greece was left devastated and the government was kept afloat only by loans from Britain, keen to cultivate an ally in the region, as well as by the activities of its merchant fleet. Eventually, King Ioannis triumphed and was able to establish himself as more than just a “first amongst equals”. He was able to push through a number of reforms that centralised power in his state. While he had gone some way toward centralising Greece however, he was left with a country which largely had no sense of itself. Local and religious identities prevailed over a national Greek identity, which made the task of governance somewhat harder. It was only in the 1850s that the beginnings of a Modern Greek identity, looking in equal parts to restore Byzantine greatness, as well as that of Classical Greece, was born.

While both Serbia and Bulgaria emulated Greece’s strategy of developing an incipient nationalism from looking back onto medieval glories, the ways in which the two states dealt with the difficult internal situations of their own countries differed. The Prince of Serbia attempted a policy of consensus, working with local elites to give them a share of power in his own government and for a time, even tolerating what remained of the Muslim populations of Serbia’s towns. By mirroring the Muslim concept of the Dhimmi, he taxed the Muslim population while allowing them a measure of freedom. In Bulgaria, the remaining Muslim population fared less well, yet those local elites who had fought alongside the new King of Bulgaria during the war for independence were allowed a great deal of autonomy. Unlike Greece which was going down the path of centralisation, the other large Balkan States were aiming for consensus and local autonomy. Yet common to all three was a sense that the national missions were not yet complete, and that more homeland remained to be liberated from the Turk.

However, following a formal alliance and a steady rise of tension at the borders, full-blown war erupted between the Balkan Nations and the Ottoman Empire in 1854. Traditionally, the narrative had been that the Balkan Alliance had underestimated Ottoman strength, though more recent studies emphasise that the war had actually been launched due to concerns about the growing strength of the Ottomans. By 1855, the Ottomans were gaining ground, and the alliance was only saved due to the intervention of the Russians, who swept the Ottomans from much of the Balkans and came within sight of Constantinople. However, following a valiant defence at Çatalca, the Turks were able to gain back some ground and establish defensible borders over a hundred kilometres from Constantinople. Despite the setback at the end of the war, the subsequent Treaty of Vienna left huge swathes of the Balkans in the hands of the new Balkan states. Despite initial scepticism amongst many in Europe about the durability of the new Balkan states, which incorporated huge heterogeneous populations, the predicted Great War for supremacy in the 1860s never occurred. This was in large part due to the need to focus on internal consolidation and general war exhaustion on the part of the Balkan Nations. As each year passed, it seemed as if the tensions which had dogged the Balkans were now beginning to lessen.

* * * * * *

James Hamlin; Great Power Politics in Europe, 1700 to 2000

Russia in the Mid 19th Century

With the Triumph of France over Austria in 1829 and the subsequent reordering of Europe which saw France preserve the Hapsburgs and Poles as a shield against Russian influence in the Continent, Russia’s influence in Europe reached its nadir. Tsar Alexander’s attempts of turning the Balkans into a Russian sphere of influence had largely failed, and had left Russia weakened for the “decisive conflict” in Europe at the end of the 1820s. His foreign policies largely recognised as failure, he turned his energy as best he could toward internal governance. For the reactionary Tsar, this meant crushing all impulses toward liberalism and nationalism, and the preservation of Russia’s autocratic system of government. A Lithuanian uprising in 1828 was crushed, as was an attempt by army officers to implement a parliament among French lines in 1830. For ten more years, the Tsar kept Russia backwards and increasingly isolated from the outside world, though in practice this did not mean that Russia saw no change. The country’s population began to grow, easily keeping pace with France’s which she would overtake in 1847. In Moscow and St Petersburg, rising rates of literacy saw the popularisation of newspapers as well as a flowering of Russian culture in which novelists such as Mikhalkov and Vorontsov made their marks.

The cities, and to some extent the Russian aristocracy began to change, with French being abandoned as the language of the aristocracy in favour of Russian. However, for the rural peasantry, approximately half of whom were not free but were serfs, there was less change in their day to day lives. Russian agriculture, outside of some modernized estates, remained medieval. The focus of day to day life was the Mir or village, to which Russian peasants including those who were free remained tied to. Unlike in North America, there was little migration to the wide open spaces to the South or to the East, and the Russian population was concentrated rather in “Old Russia” or the Ukraine. Due in part to Russia’s increasing isolation from the rest of Europe, there appeared to be little desire for reform among the majority of the population, although with so few peasants literate, this cannot be confirmed with certainty. However, peasant uprisings were still not so uncommon, especially when compared to Western and Central Europe, and the Tsar’s armies found themselves involved in many a police action.

Change at last began to come to Russia with the death of Tsar Alexander. With the accession of his son Konstantin, a reformer came to the throne of Russia, albeit one with similar expansionist tendencies as his father had possessed in his youth. However, in contrast to his father Konstantin was far less of a conservative, and believed in implementing at least some of the social, organizational and technological innovations coming from Western Europe. In 1847, Russia’s first major railway was built between St Petersburg and Great Novgorod. A system of state funded schools was established in the major cities of the Empire, and the army was reformed with the advice of a British military mission. However, despite these advances, no concessions were given toward political liberalisation, or the abolition of serfdom which had already been undertaken in the rest of Europe outside the Balkans by this point. Instead Tsar Konstantin would let the “Régime du Sabre” do its work, and win the approval of his subjects with military adventurism.

The first target of Russia was the ailing Qing Empire in China, which had recently suffered a heavy defeat at the hands of the British. Using the pretext of a territorial dispute along the Amur River, Russian troops attacked Manchuria, the homeland of the Qing. Following several defeats, the Qing signed a treaty with the Russians fixing the border in Manchuria at the Amur River. Realistically this gained Russia little in the way of economic resources or even strategic advantage, though the Tsar was keen to brandish this victory, a task made easier with the new technologies of the telegraph and photography, which allowed a front that was thousands of kilometres away from Moscow to remain within contact. With success in the Far East, as well as consistent gains against Kazakh nomads in Central Asia, Konstantin turned his eyes south to the prize that had eluded his father. The Russians had long been enemies with the Ottoman Empire, and in the past century had gained the upper hand in the conflict. Although in the 18th century the Ottomans had been protected by Persia, the 19th century saw real gains against the Ottomans, with the Crimea seized and multiple areas of the Balkans liberated in 1825.

Konstantin wanted to emulate this success, and saw his opportunity when low-scale struggles in the Balkans erupted into full scale war in the 1850s. When the international situation had become less amenable to the Ottomans, the Russians dispatched their forces south, defeating the Ottomans in a number of key battles. At home, newspapers loyal to the Tsar announced that the retaking of Constantinople or “Tsargrad” for Orthodoxy was almost in sight which inspired a great deal of euphoria among the middle classes and the religious. However, following French intervention and an Ottoman victory at Çatalca, the Russians were forced to pull back some 100 kilometres where the front stabilised. The war had won vast swathes of territory for Russia’s Balkan Allies, though Russia herself had gained little even for the loss of over 50,000 men. In the end, Russia was left exhausted and indebted due to the conflict, and had little to show for it but some rather independently minded “client states” in the Balkans. In 1859, Greece signed an alliance with the British, ending any fiction that the Balkans were the Russian sphere of influence that was hoped for.

Tsar Konstantin’s popularity never quite recovered from this setback. Unrest in the countryside was on the rise in the 1850s, and under pressure from reformists as well as the peasantry themselves, the Tsar finally followed the lead of the rest of Europe and abolished Serfdom in 1860. However, Russian peasants were still not free in the sense that those elsewhere in Europe were, as they remained tied to the village. Although this went some way toward resolving the tensions that existed in Russia, it did less to solve the problem of Russia’s growing foreign debt, or the exhaustion of her army. When Europe appeared to be on the brink of a general war in 1861, Russia was once again in no condition to be a serious player in the conflict, and it was to be this continued rehabilitation that was to sting the Russian psyche for many years to come.

* * * * * *

Author's Notes - Historically, the Balkan Kingdoms had a difficult time actually building nations. With an earlier birth, and growth into Ottoman territory, these difficulties have been far more severe than OTL. Rather than fighting each other for the scraps gained from the Ottomans, the Balkan Powers will have to struggle to hold onto what they have and prevent their states from falling apart into warlordism. This is likely to have its own significance for the development of national identities in the Balkans.

Russia appears once again to have rolled the dice at the wrong time. Cheated out of the great prize of Constantinople, it remains to be seen what Russia will do in the future. Further expansion into Europe is likely to provoke a reaction, so any expansion on the part of Russia will likely have to be timed well to exploit division on the continent. Despite Russia's setbacks though, she has undertaken a few key reforms a bit earlier than OTL. With the Ottomans destroyed as a Great Power to the south, future expansion may be directed further east in China, or dare I say south in the direction of Persia. All depends on how well Russia can exploit her growing resources.

Russia appears once again to have rolled the dice at the wrong time. Cheated out of the great prize of Constantinople, it remains to be seen what Russia will do in the future. Further expansion into Europe is likely to provoke a reaction, so any expansion on the part of Russia will likely have to be timed well to exploit division on the continent. Despite Russia's setbacks though, she has undertaken a few key reforms a bit earlier than OTL. With the Ottomans destroyed as a Great Power to the south, future expansion may be directed further east in China, or dare I say south in the direction of Persia. All depends on how well Russia can exploit her growing resources.

Last edited:

Could it have been the higher figure if the very-happy-to-be-in-the-empire peoples of Korea and Taiwan were included as part of the total?

Sounds right.

Correct. No Simon Bolivar so... yeah. I'd envisioned this revolt largely as inspired by the revolt of Tupac Amaru, and indeed the first map you drew up actually corresponds fairly closely to the territory I had in mind for the Inca, with the exception that Hispanic Peru is slightly bigger than it is in yours. As far as I'm aware (and the demographics of Peru aren't my strong suit) pretty much whole of the interior of Peru and Bolivia at this point would have been majority native at this point right?

Given that the indigenous people make up a majority of the population of Bolivia now, and perhaps 45% of the population of Peru, that's probably correct. (Of course, this is somewhat complicated by that fact that many people who are classified as native American by the sort of people who do this sort of classifying self-identify as mestizo)

You mentioned Tsar Alexander twice in the last three paragraphs. Did you mean Konstantin, instead? And when will you write about the Cape Colony and South Africa in general? (maybe you already have and i just forgot it. It that case, forgive me for my horrid sin, my memory has seen its better days). And what more will be butterflied away? Uuuuuhhh the hype is killing me!

Konstantin wanted to emulate this success, and saw his opportunity when low-scale struggles in the Balkans erupted into full scale war in the 1850s. When the international situation had become less amenable to the Ottomans, the Russians dispatched their forces south, defeating the Ottomans in a number of key battles. At home, newspapers loyal to the Tsar announced that the retaking of Constantinople or “Tsargrad” for Orthodoxy was almost in sight which inspired a great deal of euphoria among the middle classes and the religious. However, following French intervention and an Ottoman victory at Çatalca, the Russians were forced to pull back some 100 kilometres where the front stabilised. The war had won vast swathes of territory for Russia’s Balkan Allies, though Russia herself had gained little even for the loss of over 50,000 men. In the end, Russia was left exhausted and indebted due to the conflict, and had little to show for it but some rather independently minded “client states” in the Balkans. In 1859, Greece signed an alliance with the British, ending any fiction that the Balkans were the Russian sphere of influence that was hoped for.

If Russia never gets it's hand on Constantinople, will their be any hope of liberating the city from Turkish rule in the future?

As each year passed, it seemed as if the tensions which had dogged the Balkans were now beginning to lessen.

Seemed? Uh oh.

And Russia continues to find itself lagging behind everyone else in political reform. If the liberation of the serfs goes something like OTL, then the old landlords would hike up the price for the best lands they have, further aggravating the freed farmers. Maybe that would finally drive the peasant class to migrate around the empire, or beyond.

If Russia never gets it's hand on Constantinople, will their be any hope of liberating the city from Turkish rule in the future?

Probably not. With the war turn out to be waste of money and manpower and little to no gain from it. And no other balkan except maybe greece want to continue the war against the turk but if greece gone too far someone else may see the opportunity to stab her in the back especially regarding macedonia question (greece is the one who get aegean macedonia ittl right?)

And ottoman in this tl is different creatures from otl with higher literacy among her populace. Heh I wonder with nassirisimo said russia plan to make a move against Iran what gain they want to have from that war? Aside to gain some land will russia try to reduce persia to mere puppet maybe?

Probably not. With the war turn out to be waste of money and manpower and little to no gain from it. And no other balkan except maybe greece want to continue the war against the turk but if greece gone too far someone else may see the opportunity to stab her in the back especially regarding macedonia question (greece is the one who get aegean macedonia ittl right?)

It's a shame since I don't many threads about the religious consequences of the Eastern Rome reborn.

It's a shame since I don't many threads about the religious consequences of the Eastern Rome reborn.

Well to be fair I also want to see a tl where russia less successful in baltic but black sea and the strait under some form of russian control either directly or indirectly and have some influence in mediterranian sea. Probably need a pod so far back before both french and british have real interest in eastern mediterranian

Well to be fair I also want to see a tl where russia less successful in baltic but black sea and the strait under some form of russian control either directly or indirectly and have some influence in mediterranian sea. Probably need a pod so far back before both french and british have real interest in eastern mediterranian

And easy one would be killing Mahmud II during the Ottoman Coups of 1807-08, which would make the empire fall apart.

Just read through the whole timeline, and it's definitely one of my favorite on the site! Fantastic job!

Threadmarks

View all 61 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Africa - 1829 to 1862 South and Central America - 1829 to 1862 North America - 1829 to 1862 Eastern Europe - 1829 to 1862 Central Europe - 1829 to 1860 Western Europe - 1829 to 1860 The European Revolutions - 1860 The European Revolutions - 1861

Share: