You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

From the Ashes of the Old: The British Republic

- Thread starter President Conor

- Start date

Chapter Eight: Gordon-Lennox and Attwood

The legacy of Charles Gordon-Lennox will be bittersweet. Yes, he led to the break-up of an empire and a state that was regarded by January 1848 as a failure. But to the revolutionaries and founding fathers he was regarded in the end as the man who would symbol that there was nothing left for people to believe in the old regime. That need for reform, and that need for revolution were realised in the 85 days of his premiership.

Bill Clinton, 1970

Charles Gordon-Lennox, the first and last 'High Protector' of the United Kingdom

By the turn of the year in 1848, Earl Bathurst was in despair at the current state of affairs in the country. Having seized control of Dublin, the Irish Republic had orchestrated similar gains in Limerick and Cork and by this time, controlled much of the south of the country and had begun a political spring unseen in most of the continent and the country. He sought counsel with many of his cabinet and the response was a letter signed by 16 members, that a series of democratic reforms would have to be undertook to control the first colony and prevent a brewing Civil War across the country as a whole. He responded to this was to produce at great hast the 'Bathurst Papers' - a blueprint for the rollback of the governmental control that had manifested itself over the past 35 years. Firstly, Bureaus would increase their power and would be directly elected by those who contributed to it. This would begin in May 1848 and would end in December 1848 with the first truly elected government in Great Britain. The plan was received well in Republican camps and Attwood himself declared it to be the beginning of a slow transition to a Republic - 'a republic of erosion', he referred to it in a letter to Fergus O'Connor on New Years Day, 1848. Candle-light vigils were held in Huddersfield to commemorate the papers publication and similar events were held in Leeds, Manchester and Birmingham, which Attwood himself attended.

Inside Parliament, however, the mood was not universally positive. A growing number of National Front politicians, led by Charles Gordon-Lennox, were opposed to the move and the Home Secretary sought an audience with the Queen, who had quietly ascended to the throne just two years earlier replacing a council of regents after the death of William IV in 1844. Victoria, seen as a more Liberal monarch than both the council and her father, was told that any attempt to reform the government would not aid the growing lawlessness and civil disobedience brewing in the country, but would most likely increase it. On January 3rd 1848, just two days after the reforms had seen many cities, plagued by riots and violence by both National and Popular Front members, Gordon-Lennox, along with a few members of the National Front militia dressed in Checkers uniforms, entered 10 Downing Street and forcibly removed Earl Bathurst. As Popular Front members in the area saw this as a Coup D'Etat, they followed the men in and engaged in a rifle battle, forming barricades and protecting the Earl from the National Front men. As the ran to the gates of the street, one man grabbed the Prime Minister and shot him in the stomach, leaving him badly wounded. A few hours later in the modern day Thomas Attwood Hospital, he died of his wounds to the shock of a nation.

In the immediate aftermath, Gordon-Lennox seized power and arrested and removed the 16 members of the cabinet who had co-signed the letter. He sought to point the blame of the assassination on the Popular Front members who had attempted to protect him, and had the 10 men who arrived at Downing Street hung in Parliament Square that day. Citing the growing instability of the country, he sought approval from the monarch to appoint a new government with him as the 'High Protector' and suspend public gatherings and Parliament. A young woman at the time, she approved the measures under advice of Gordon-Lennox himself, who had developed an excellent relationship with the Queen.

Across the northern cities and in London, measures were taken to control an unruly populous. However, as many Soldiers were confined to their barracks and National Front men were conducting the raids themselves, the Army quickly began to turn against the new regime. When the Front men arrived at the offices of the Manchester Bureau, they found a heavily armed resistance from a group of GPPU men who had sought to protect the Wardens there. As they fought back, they were heavy battles between the two factions, and after three hours of fighting, the Union Jack which topped the building was removed and replaced with the flag of the Popular Front, quickly painted on cloth in the building and stained with blood - the green, white and purple of a new Republic. They stood on the steps after the National Front men had retreated and proclaimed to a nearly empty square;

We, sons of men who have lived under tyranny for generations reject the Government of the men who seek to murder us and our comrades across the country. It is the right of man to change course when the situation around them has failed them, and we proclaim in this city an end to the oppression of the generations of the Government and of the rule of the monarch for which that Government seeks and attains its legitimacy. We raise the flag of our united front against this tyranny and declare that, as Thomas Attwood said, we can be the next peoples to rule themselves in the name of Responsible Government. This, from this day, the 3rd January 1848, is the establishment of the Free City of Manchester, ruled by no-one other than the citizens and comrades within it for the benefit of all within it.

As the men raised their rifles, the sent contact to all of the Popular Front in the city to seize control and push back the Government. Thomas Attwood was informed of this on his way back to Birmingham, where he was intended to be hidden for a few days in fear of a National Front attack. He immediately sought to go back to Birmingham City Bureau, and meet Thomas Farrar, at this point a leading member of the GPPU in London, and O'Connor. He would, in this meeting tell them that John Thadeus Delane was returning to Britain, and the time had come to prepare for the end of the Monarchy and its replacement with a Radical Republic.

The legacy of Charles Gordon-Lennox will be bittersweet. Yes, he led to the break-up of an empire and a state that was regarded by January 1848 as a failure. But to the revolutionaries and founding fathers he was regarded in the end as the man who would symbol that there was nothing left for people to believe in the old regime. That need for reform, and that need for revolution were realised in the 85 days of his premiership.

Bill Clinton, 1970

Charles Gordon-Lennox, the first and last 'High Protector' of the United Kingdom

By the turn of the year in 1848, Earl Bathurst was in despair at the current state of affairs in the country. Having seized control of Dublin, the Irish Republic had orchestrated similar gains in Limerick and Cork and by this time, controlled much of the south of the country and had begun a political spring unseen in most of the continent and the country. He sought counsel with many of his cabinet and the response was a letter signed by 16 members, that a series of democratic reforms would have to be undertook to control the first colony and prevent a brewing Civil War across the country as a whole. He responded to this was to produce at great hast the 'Bathurst Papers' - a blueprint for the rollback of the governmental control that had manifested itself over the past 35 years. Firstly, Bureaus would increase their power and would be directly elected by those who contributed to it. This would begin in May 1848 and would end in December 1848 with the first truly elected government in Great Britain. The plan was received well in Republican camps and Attwood himself declared it to be the beginning of a slow transition to a Republic - 'a republic of erosion', he referred to it in a letter to Fergus O'Connor on New Years Day, 1848. Candle-light vigils were held in Huddersfield to commemorate the papers publication and similar events were held in Leeds, Manchester and Birmingham, which Attwood himself attended.

Inside Parliament, however, the mood was not universally positive. A growing number of National Front politicians, led by Charles Gordon-Lennox, were opposed to the move and the Home Secretary sought an audience with the Queen, who had quietly ascended to the throne just two years earlier replacing a council of regents after the death of William IV in 1844. Victoria, seen as a more Liberal monarch than both the council and her father, was told that any attempt to reform the government would not aid the growing lawlessness and civil disobedience brewing in the country, but would most likely increase it. On January 3rd 1848, just two days after the reforms had seen many cities, plagued by riots and violence by both National and Popular Front members, Gordon-Lennox, along with a few members of the National Front militia dressed in Checkers uniforms, entered 10 Downing Street and forcibly removed Earl Bathurst. As Popular Front members in the area saw this as a Coup D'Etat, they followed the men in and engaged in a rifle battle, forming barricades and protecting the Earl from the National Front men. As the ran to the gates of the street, one man grabbed the Prime Minister and shot him in the stomach, leaving him badly wounded. A few hours later in the modern day Thomas Attwood Hospital, he died of his wounds to the shock of a nation.

In the immediate aftermath, Gordon-Lennox seized power and arrested and removed the 16 members of the cabinet who had co-signed the letter. He sought to point the blame of the assassination on the Popular Front members who had attempted to protect him, and had the 10 men who arrived at Downing Street hung in Parliament Square that day. Citing the growing instability of the country, he sought approval from the monarch to appoint a new government with him as the 'High Protector' and suspend public gatherings and Parliament. A young woman at the time, she approved the measures under advice of Gordon-Lennox himself, who had developed an excellent relationship with the Queen.

Across the northern cities and in London, measures were taken to control an unruly populous. However, as many Soldiers were confined to their barracks and National Front men were conducting the raids themselves, the Army quickly began to turn against the new regime. When the Front men arrived at the offices of the Manchester Bureau, they found a heavily armed resistance from a group of GPPU men who had sought to protect the Wardens there. As they fought back, they were heavy battles between the two factions, and after three hours of fighting, the Union Jack which topped the building was removed and replaced with the flag of the Popular Front, quickly painted on cloth in the building and stained with blood - the green, white and purple of a new Republic. They stood on the steps after the National Front men had retreated and proclaimed to a nearly empty square;

We, sons of men who have lived under tyranny for generations reject the Government of the men who seek to murder us and our comrades across the country. It is the right of man to change course when the situation around them has failed them, and we proclaim in this city an end to the oppression of the generations of the Government and of the rule of the monarch for which that Government seeks and attains its legitimacy. We raise the flag of our united front against this tyranny and declare that, as Thomas Attwood said, we can be the next peoples to rule themselves in the name of Responsible Government. This, from this day, the 3rd January 1848, is the establishment of the Free City of Manchester, ruled by no-one other than the citizens and comrades within it for the benefit of all within it.

As the men raised their rifles, the sent contact to all of the Popular Front in the city to seize control and push back the Government. Thomas Attwood was informed of this on his way back to Birmingham, where he was intended to be hidden for a few days in fear of a National Front attack. He immediately sought to go back to Birmingham City Bureau, and meet Thomas Farrar, at this point a leading member of the GPPU in London, and O'Connor. He would, in this meeting tell them that John Thadeus Delane was returning to Britain, and the time had come to prepare for the end of the Monarchy and its replacement with a Radical Republic.

Amazing!

Boy am I a fan of this timeline.

Cheers, got a lot more time off so I should add the next three instalments very quickly this week.

Chapter Nine: An Absurd Normalcy

In the first few weeks, months of the revolution, the country was in a paralysed state. Two factions, one clinging to the embers of a fading fire and one desperately trying to control the blaze within its citizens. Emotion and dogma ruled over sense. The losers? A generation of young men and women who fought for their beliefs, a nation who couldn't look back without a strange and frightful regret.

General Kurt Von Schliecher, 1938

William Carr Beresford, first Commander of the Army of the British Republic, a key figure in the Revolutionary Wars of 1849.

As a gunshot cracked through the air in Bow, London, few men stopped to turn and notice, nobody stopped, no-one quivered. It had become almost a sound as common as the chatter of the streets and the bustle of everyday life in our capital. As January turned to February, conflict had turned to an almighty and bloody stalemate in Britain.

Further north, Manchester, Leeds, Hull, Birmingham, Liverpool and much of Scotland had joined Ireland in their declaration of freedom from the United Kingdom. 'Town Hall Republics' had been formed across the north, with young middle class and working men and women occupying their cities and building a new kind of state - the Federation of British Free Cities and Republics had formed the prototype of the Constitution today. Thomas Attwood headed the organisation from the Birmingham Town Hall, coordinating supplies and men across the network of individual republics. In the Free City of Manchester, John Thadeus Delane worked in the office aimed at moving and coordinating information across the fronts in Derby, Grimsby, Sheffield all the way down to Newport, where the Republicans had pushed the Government troops to the edge of the Welsh border.

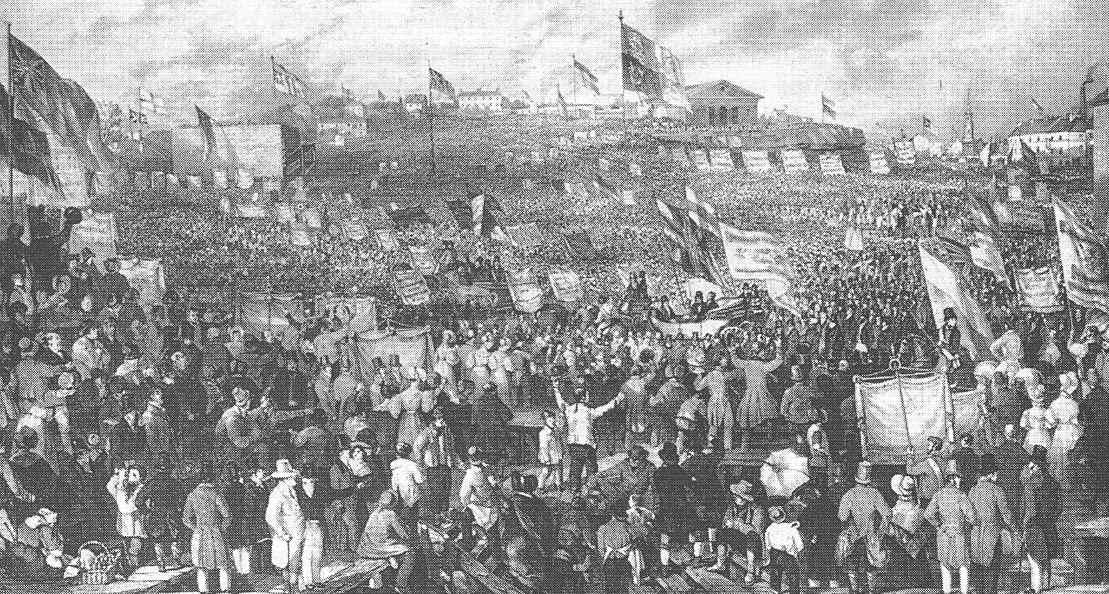

Fergus O'Connor had embarked on a tour of the new Republics, seeking to improve morale and enlist volunteers for the British Republican Brotherhood and British Republican Army. From Glasgow to Newcastle, Leeds to Manchester he spoke to large crowds about a new dawn, a new republic stretching from Southampton to Aberdeen and beyond. "Is it not strange, my friends, that we have lived in this country since our birth yet never had the audacity to ask for a stake in its future further than a cut of our wages?" he said to a roaring crowd in Manchester, one month after the revolution.

As dawn rose on the 1st March, 1848, the last father of the modern British Republic was sat, on the back of a horse and cart, on his way down to a steam-boat to Jersey. Thomas Farrar, disguised and facing a death warrant from the Government of National Salvation, formed in the aftermath of the 'unrest' sweeping across the north, went in search of a military grandee and son of the 1820 Liberal Revolution in Portugal.

After the descent in Britain into authoritarianism, Portugal too came under the increasing grasp of British influence. It's king, Joao VI, loosened his grip on the region after leaving to rule from Brazil in 1811, citing a fear of capture at the hands of Napoleon. When the threat was quelled at the end of the Napoleonic Wars, Joao did not return. This left a power vacuum the British were keen to fill with a mainland European influence. They installed a government, headed Prince Miguel I, with Joao nominally as the absolute ruler but in reality, in no such position to argue with the control the British Army had on the region.

Beresford, an aristocrat by nature, settled into a high ranking role within the regime. He assumed the position of Marshall, and oversaw maintaining the British Empire's first European colony. Slowly, the country became closer and closer aligned to Britain - town names were changed, English used on all official forms and the country by 1819 had a very British feel to it. The City of Port Douro (formally Oporto/Porto) was lined with British goods and a great many Britons were stationed there. Beresford proclaimed that the city was 'like Southampton bathed in Sunshine'.

In 1820, a small protest in Port Douro against the colonisation quickly spread across the north of the country. The British interest was threatened, and Beresford, benefiting from his influence at Whitehall, tried to persuade the Government to release control and allow home rule for Portugal. This was based in the fact that a release of the tightened grip would allow the continual of the British interest through mutual cooperation. Spencer Perceval, seeking to consolidate his European influence, dismissed his suggestion and ordered Martial Law in Portugal. A revolution broke on the 3rd January 1820, which quickly deposed Miguel's Government, and replaced it with a constitutional monarchy under Joao VI, who returned from Brazil to rule. Beresford was a forgotten man, who was quickly retired from the British Army, and disgraced at his suggestion to reel back the controlling nature of the regime. He settled into a Governor's role in Jersey, which sought to respect his tradition and his military career, but sideline him from decision-making. Despite this, as the word broke of his actions in Portugal, he became associated with the new Government in Lisbon and visited many times, often doing so in secret as to not arise suspicion from Whitehall, or to reduce the risk of a 'disappearance' on his way home. He became amassed to Liberal ideas, and as the state blossomed under the leadership, he informally rolled back some of the restrictions on political movement in Jersey, although he remained a committed Conservative until his final days.

Despite this, Farrar was not interested in his politics. Farrar was interested in his work in the Peninsular Wars - coordinating a campaign of ambush and guerrilla warfare in Iberia. He sought to draft him into the Popular Front to remove the heirs of the Perceval regime. Upon his arrival in Jersey, he was taken to the residence, itself a dangerous move. He asked him to leave Jersey and coordinate the overthrow of the Government. Initially he refused, but as the conversation went on, he was told of the regimes actions in the Northern cities and the control in the south. He told Farrar that he could be in Manchester in five days, and would assume control of the Popular Front. In exchange, he would be allowed to return to political life once the regime was ousted.

Once Farrar returned to Birmingham - he said to Attwood.

"We have our man"

In the first few weeks, months of the revolution, the country was in a paralysed state. Two factions, one clinging to the embers of a fading fire and one desperately trying to control the blaze within its citizens. Emotion and dogma ruled over sense. The losers? A generation of young men and women who fought for their beliefs, a nation who couldn't look back without a strange and frightful regret.

General Kurt Von Schliecher, 1938

William Carr Beresford, first Commander of the Army of the British Republic, a key figure in the Revolutionary Wars of 1849.

As a gunshot cracked through the air in Bow, London, few men stopped to turn and notice, nobody stopped, no-one quivered. It had become almost a sound as common as the chatter of the streets and the bustle of everyday life in our capital. As January turned to February, conflict had turned to an almighty and bloody stalemate in Britain.

Further north, Manchester, Leeds, Hull, Birmingham, Liverpool and much of Scotland had joined Ireland in their declaration of freedom from the United Kingdom. 'Town Hall Republics' had been formed across the north, with young middle class and working men and women occupying their cities and building a new kind of state - the Federation of British Free Cities and Republics had formed the prototype of the Constitution today. Thomas Attwood headed the organisation from the Birmingham Town Hall, coordinating supplies and men across the network of individual republics. In the Free City of Manchester, John Thadeus Delane worked in the office aimed at moving and coordinating information across the fronts in Derby, Grimsby, Sheffield all the way down to Newport, where the Republicans had pushed the Government troops to the edge of the Welsh border.

Fergus O'Connor had embarked on a tour of the new Republics, seeking to improve morale and enlist volunteers for the British Republican Brotherhood and British Republican Army. From Glasgow to Newcastle, Leeds to Manchester he spoke to large crowds about a new dawn, a new republic stretching from Southampton to Aberdeen and beyond. "Is it not strange, my friends, that we have lived in this country since our birth yet never had the audacity to ask for a stake in its future further than a cut of our wages?" he said to a roaring crowd in Manchester, one month after the revolution.

As dawn rose on the 1st March, 1848, the last father of the modern British Republic was sat, on the back of a horse and cart, on his way down to a steam-boat to Jersey. Thomas Farrar, disguised and facing a death warrant from the Government of National Salvation, formed in the aftermath of the 'unrest' sweeping across the north, went in search of a military grandee and son of the 1820 Liberal Revolution in Portugal.

After the descent in Britain into authoritarianism, Portugal too came under the increasing grasp of British influence. It's king, Joao VI, loosened his grip on the region after leaving to rule from Brazil in 1811, citing a fear of capture at the hands of Napoleon. When the threat was quelled at the end of the Napoleonic Wars, Joao did not return. This left a power vacuum the British were keen to fill with a mainland European influence. They installed a government, headed Prince Miguel I, with Joao nominally as the absolute ruler but in reality, in no such position to argue with the control the British Army had on the region.

Beresford, an aristocrat by nature, settled into a high ranking role within the regime. He assumed the position of Marshall, and oversaw maintaining the British Empire's first European colony. Slowly, the country became closer and closer aligned to Britain - town names were changed, English used on all official forms and the country by 1819 had a very British feel to it. The City of Port Douro (formally Oporto/Porto) was lined with British goods and a great many Britons were stationed there. Beresford proclaimed that the city was 'like Southampton bathed in Sunshine'.

In 1820, a small protest in Port Douro against the colonisation quickly spread across the north of the country. The British interest was threatened, and Beresford, benefiting from his influence at Whitehall, tried to persuade the Government to release control and allow home rule for Portugal. This was based in the fact that a release of the tightened grip would allow the continual of the British interest through mutual cooperation. Spencer Perceval, seeking to consolidate his European influence, dismissed his suggestion and ordered Martial Law in Portugal. A revolution broke on the 3rd January 1820, which quickly deposed Miguel's Government, and replaced it with a constitutional monarchy under Joao VI, who returned from Brazil to rule. Beresford was a forgotten man, who was quickly retired from the British Army, and disgraced at his suggestion to reel back the controlling nature of the regime. He settled into a Governor's role in Jersey, which sought to respect his tradition and his military career, but sideline him from decision-making. Despite this, as the word broke of his actions in Portugal, he became associated with the new Government in Lisbon and visited many times, often doing so in secret as to not arise suspicion from Whitehall, or to reduce the risk of a 'disappearance' on his way home. He became amassed to Liberal ideas, and as the state blossomed under the leadership, he informally rolled back some of the restrictions on political movement in Jersey, although he remained a committed Conservative until his final days.

Despite this, Farrar was not interested in his politics. Farrar was interested in his work in the Peninsular Wars - coordinating a campaign of ambush and guerrilla warfare in Iberia. He sought to draft him into the Popular Front to remove the heirs of the Perceval regime. Upon his arrival in Jersey, he was taken to the residence, itself a dangerous move. He asked him to leave Jersey and coordinate the overthrow of the Government. Initially he refused, but as the conversation went on, he was told of the regimes actions in the Northern cities and the control in the south. He told Farrar that he could be in Manchester in five days, and would assume control of the Popular Front. In exchange, he would be allowed to return to political life once the regime was ousted.

Once Farrar returned to Birmingham - he said to Attwood.

"We have our man"

Quite an interesting update. Will you go into detail on how the colonies at the time will react to Britain becoming a republic?

Quite an interesting update. Will you go into detail on how the colonies at the time will react to Britain becoming a republic?

There will be a colony update, but at this time in 1848, the Colonies are under the control of the Kingdom. There is unrest in some, but this is mainly political and taking place between administrations in the colonies as to who they should recognise as their colonial power.

More to come soon!

There will be a colony update, but at this time in 1848, the Colonies are under the control of the Kingdom. There is unrest in some, but this is mainly political and taking place between administrations in the colonies as to who they should recognise as their colonial power.

More to come soon!

That is not innaccurate wonder how european nations will react

I think unease will be the order of the day, however a few allies will develop for the new regime in unlikely places. The balance of power shifting away from Monarchy will be felt with a rather cast iron block across the continent going well into the future.That is not innaccurate wonder how european nations will react

That is neat. Wonder if this changes the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire the Crimean War of OTL is few years awayI think unease will be the order of the day, however a few allies will develop for the new regime in unlikely places. The balance of power shifting away from Monarchy will be felt with a rather cast iron block across the continent going well into the future.

Hi Everyone,

Will be reviving this timeline in the next week or so, just working through the scenario and getting back into zone for writing.

Will be reviving this timeline in the next week or so, just working through the scenario and getting back into zone for writing.

Hi Everyone,

Will be reviving this timeline in the next week or so, just working through the scenario and getting back into zone for writing.

Still wondering what will happen to the colonies now that the former government is removed

Chapter Ten: Piecing Together a Republic

"Mr Attwood, the holes in this country cannot be solved with a patchwork - we must forge a new society of mutual assurance, mutual assistance. We must not replace a King with a King-in-Name and we must not replace our Federation with a Kingdom-in-Name."

Thomas Farrar's letter to Thomas Attwood about the passing of the Treaty of Hull, March 1848.

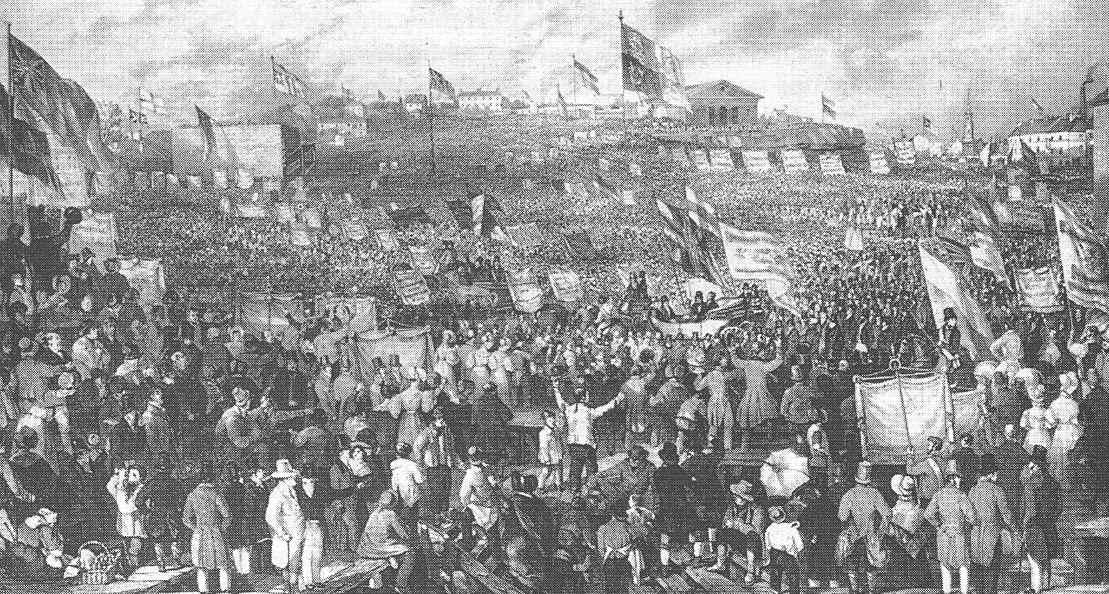

A Member of the British Republican Brotherhood addresses a crowd of Farmers about the passing of the Covenant in North Yorkshire, 13th May 1848

"The question of how strong a country is, my friend, intertwined with how ready its men are to defend it" said William Carr Beresford to Thomas Attwood on the 10th March 1848. "I saw the impact of a regime that failed to include the masses in the upkeep of the state. It was crushed and all the men, arms and naval power could not prevent that."

Beresford's insistence that his control of the Popular Front came with strict control over its organisation and composition worried members of the GPPU and especially Attwood initially. Farrar's recommendation only sought to provide amusement amongst the Federation and the approach was only made as Attwood persuaded them, providing Farrar find the man himself. Farrar took this literally, of course, and while returning back, his bodyguards found themselves caught by National Front men, where a gun battle ensued. Farrar was told to flee when one of the National Front column attacked him with a knife, gashing his left foot, before being shot by one of his men. When he returned, Attwood said "your sacrifice has been great, and makes your recommendation blood-bound", to which Farrar responded "If it weren't for my men, I wouldn't have returned at all".

The British Army, Beresford informed Attwood, was stretched between America, India and Australia, and while it's naval power was unquestionable, it could be defeated on land, and in effect, locked out of its motherland. While rump armies would fight their way to London, they would do so only to allow enough time for reinforcements from across the Empire. Therefore, a defensive strategy, with a well oiled, well trained elite force would be much more effective for their key territories of Birmingham, Leeds, and the key coastal areas. While these would secure key assets gained, a guerrilla campaign could be ensued of the enthusiastic masses of the Popular Front. A well guarded state that could protect Democracy, and an expansionist destiny to encapsulate all of Britain through a war of conversion.

Beresford quickly assembled the British Republican Army Guards, who formed a protective shield of trenches across from the Federation's border, from Grimsby to Newport. On seeing this military wall built, many south of the border felt trapped under the Government of National Salvation, and that the New Republic's had cut them off.

In Birmingham, a convention was announced to see a discussion of the next steps of the Revolution.

At the Convention, motions from the names of a new currency for the Republic to individual Republic's power to the power structures that would define it in peacetime were debated by representatives from across the Union. On the latter, Fergus O'Connor proposed a motion to create a single, elected President who would form a powerful central Government for the whole union, elected in 1849. Farrar bitterly opposed, joining the protests of the Governments of Ireland, Scotland and Wales, and Attwood, who insisted that a Confederation with a looser, Presidential Council and rotating Presidency would allow enough decentralised control to allow all people to have their voices heard. He was defeated narrowly, by 134-128. After the defeat, he gathered his supporters in the vote, and together they formed the National Liberal Alliance, later the Liberal Party.

On the final day of the convention, packing into Birmingham Town Hall, the delegates signed "The Covenant of the United States of the British Republic", essentially binding all the states into a single confederation. The Republics or Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Yorkshire, Lancashire and Cumbria, and the Free Cities of Manchester and Birmingham all rose the Purple, White and Green of the British Republican Flag next to their own on the 28th March 1848, Convention Day.

The Final Signatory of the Covenant was a structural anomaly of the Revolutions in Britain of January and February. Across the North Eastern Coast, when the Revolution broke out, many Popular Front volunteers from Yorkshire and Cumbria travelled to liberate the Port Cities of Newcastle and Hull, and in doing so, rid them of the complex Bureaucracy of the Maritime trading towns.

As they left in late January back to their homelands, a power vacuum emerged and British Ports were in fierce danger of losing their vital economic trading power. Fearing a crippling economic depression, the 'Coastal Confederation' was formed of Businessmen, Traders and the remaining bureaucracy and began to function in a similar way to the other republics. They quickly raised a Merchant Navy from deserted Naval Ships to protect them from the Royal Naval blockade, basic currency, a taxation system, a police force and a system for governance. They saw themselves as completely separate from the Revolution. As Merchants returns in mid-February, they were shocked to see Britain open for business, and quickly the East Coast became the richest area in the whole country.

Attwood sent Farrar to Hull to discuss with its leaders aligning with the Revolution. They had already allowed Popular Front troops to fortify areas of Grimsby, their Southern tip, but had refused to fly the British Republican flag. Winning them over would allow the Republic to have access to shipping routes, guarded by a Merchant Navy who could gain the Republic access to a Naval Corridor for Trade. Farrar was told that they would join the Republic, but wanted sole access over their economy, and to continue to keep their taxation systems and new laws designed to protect Merchants and Traders. He agreed and returned with a draft Treaty of Hull, to ensure that the Coastal Confederation would join the British Republic as it's 9th Republic.

The Republics discussed the Treaty in the Free City of Manchester a week later, with a sole Representative from each Republic forming the General Council of the British Republic, created in the Covenant. Fergus O'Connor, who had been sent from the Irish Dail (as he was the only one in the city at the time), argued that no exceptions to the future organic law of the Republic should be compromised, not least for traders and those who refused to join the Convention. Attwood, representing Birmingham and the Chairman of the Council (having been elected at the start of the meeting unopposed) argued that Farrar had secured the Republic badly needed access to the sea, and that individual Republic's autonomy being questioned would undermine the Revolution.

O'Connor used his influence from his Liberal Alliance to gain votes from Yorkshire, who wished to reintegrate these lands into the Yorkshire Republic, and Cumbria and Lancashire, who feared that their Ports would join the Confederation if the body was integrated. However Farrar's influence in the Socialist inclined Republics in Ireland, Scotland and Wales, and Attwood influence in the Free Cities saw O'Connor defeated again, and the Treaty of Hull was ratified five votes to three. O'Connor had felt as though a power bloc were forming without him, and wrote to Attwood on the 11th April;

"As I see it, the dictatorial control of this Republic is vastly being seized by you, Thomas. It would help if you would listen to the cries of the people who brought you this position and protected them, instead of Merchants, Traders and the people who have profited from the Revolution. We will see this out together, old friend, but we must seek the passage of democracy, I feel, to save you from yourself."

"Mr Attwood, the holes in this country cannot be solved with a patchwork - we must forge a new society of mutual assurance, mutual assistance. We must not replace a King with a King-in-Name and we must not replace our Federation with a Kingdom-in-Name."

Thomas Farrar's letter to Thomas Attwood about the passing of the Treaty of Hull, March 1848.

A Member of the British Republican Brotherhood addresses a crowd of Farmers about the passing of the Covenant in North Yorkshire, 13th May 1848

"The question of how strong a country is, my friend, intertwined with how ready its men are to defend it" said William Carr Beresford to Thomas Attwood on the 10th March 1848. "I saw the impact of a regime that failed to include the masses in the upkeep of the state. It was crushed and all the men, arms and naval power could not prevent that."

Beresford's insistence that his control of the Popular Front came with strict control over its organisation and composition worried members of the GPPU and especially Attwood initially. Farrar's recommendation only sought to provide amusement amongst the Federation and the approach was only made as Attwood persuaded them, providing Farrar find the man himself. Farrar took this literally, of course, and while returning back, his bodyguards found themselves caught by National Front men, where a gun battle ensued. Farrar was told to flee when one of the National Front column attacked him with a knife, gashing his left foot, before being shot by one of his men. When he returned, Attwood said "your sacrifice has been great, and makes your recommendation blood-bound", to which Farrar responded "If it weren't for my men, I wouldn't have returned at all".

The British Army, Beresford informed Attwood, was stretched between America, India and Australia, and while it's naval power was unquestionable, it could be defeated on land, and in effect, locked out of its motherland. While rump armies would fight their way to London, they would do so only to allow enough time for reinforcements from across the Empire. Therefore, a defensive strategy, with a well oiled, well trained elite force would be much more effective for their key territories of Birmingham, Leeds, and the key coastal areas. While these would secure key assets gained, a guerrilla campaign could be ensued of the enthusiastic masses of the Popular Front. A well guarded state that could protect Democracy, and an expansionist destiny to encapsulate all of Britain through a war of conversion.

Beresford quickly assembled the British Republican Army Guards, who formed a protective shield of trenches across from the Federation's border, from Grimsby to Newport. On seeing this military wall built, many south of the border felt trapped under the Government of National Salvation, and that the New Republic's had cut them off.

In Birmingham, a convention was announced to see a discussion of the next steps of the Revolution.

At the Convention, motions from the names of a new currency for the Republic to individual Republic's power to the power structures that would define it in peacetime were debated by representatives from across the Union. On the latter, Fergus O'Connor proposed a motion to create a single, elected President who would form a powerful central Government for the whole union, elected in 1849. Farrar bitterly opposed, joining the protests of the Governments of Ireland, Scotland and Wales, and Attwood, who insisted that a Confederation with a looser, Presidential Council and rotating Presidency would allow enough decentralised control to allow all people to have their voices heard. He was defeated narrowly, by 134-128. After the defeat, he gathered his supporters in the vote, and together they formed the National Liberal Alliance, later the Liberal Party.

On the final day of the convention, packing into Birmingham Town Hall, the delegates signed "The Covenant of the United States of the British Republic", essentially binding all the states into a single confederation. The Republics or Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Yorkshire, Lancashire and Cumbria, and the Free Cities of Manchester and Birmingham all rose the Purple, White and Green of the British Republican Flag next to their own on the 28th March 1848, Convention Day.

The Final Signatory of the Covenant was a structural anomaly of the Revolutions in Britain of January and February. Across the North Eastern Coast, when the Revolution broke out, many Popular Front volunteers from Yorkshire and Cumbria travelled to liberate the Port Cities of Newcastle and Hull, and in doing so, rid them of the complex Bureaucracy of the Maritime trading towns.

As they left in late January back to their homelands, a power vacuum emerged and British Ports were in fierce danger of losing their vital economic trading power. Fearing a crippling economic depression, the 'Coastal Confederation' was formed of Businessmen, Traders and the remaining bureaucracy and began to function in a similar way to the other republics. They quickly raised a Merchant Navy from deserted Naval Ships to protect them from the Royal Naval blockade, basic currency, a taxation system, a police force and a system for governance. They saw themselves as completely separate from the Revolution. As Merchants returns in mid-February, they were shocked to see Britain open for business, and quickly the East Coast became the richest area in the whole country.

Attwood sent Farrar to Hull to discuss with its leaders aligning with the Revolution. They had already allowed Popular Front troops to fortify areas of Grimsby, their Southern tip, but had refused to fly the British Republican flag. Winning them over would allow the Republic to have access to shipping routes, guarded by a Merchant Navy who could gain the Republic access to a Naval Corridor for Trade. Farrar was told that they would join the Republic, but wanted sole access over their economy, and to continue to keep their taxation systems and new laws designed to protect Merchants and Traders. He agreed and returned with a draft Treaty of Hull, to ensure that the Coastal Confederation would join the British Republic as it's 9th Republic.

The Republics discussed the Treaty in the Free City of Manchester a week later, with a sole Representative from each Republic forming the General Council of the British Republic, created in the Covenant. Fergus O'Connor, who had been sent from the Irish Dail (as he was the only one in the city at the time), argued that no exceptions to the future organic law of the Republic should be compromised, not least for traders and those who refused to join the Convention. Attwood, representing Birmingham and the Chairman of the Council (having been elected at the start of the meeting unopposed) argued that Farrar had secured the Republic badly needed access to the sea, and that individual Republic's autonomy being questioned would undermine the Revolution.

O'Connor used his influence from his Liberal Alliance to gain votes from Yorkshire, who wished to reintegrate these lands into the Yorkshire Republic, and Cumbria and Lancashire, who feared that their Ports would join the Confederation if the body was integrated. However Farrar's influence in the Socialist inclined Republics in Ireland, Scotland and Wales, and Attwood influence in the Free Cities saw O'Connor defeated again, and the Treaty of Hull was ratified five votes to three. O'Connor had felt as though a power bloc were forming without him, and wrote to Attwood on the 11th April;

"As I see it, the dictatorial control of this Republic is vastly being seized by you, Thomas. It would help if you would listen to the cries of the people who brought you this position and protected them, instead of Merchants, Traders and the people who have profited from the Revolution. We will see this out together, old friend, but we must seek the passage of democracy, I feel, to save you from yourself."

Last edited:

Chapter Eleven: The Politicking Game

"The Period between April and May in 1848 was a turning point for the Republic. A defeat at King's Lynn, a few more soldiers for the Loyalists and it might well have developed into a stale-mate. An election of Fergus O'Connor and it might well have been a Napoleonic Shift in the Republic's formative years. The Result of May was the stable founding of a vision based on Farrar's principles of mutual assurance and mutual decision making. For better or worse, May set the course for the British Republic as we know it today."

Andrew Marr, 2014

May 1848 meeting of the Republic of Lancashire Assembly, electing Thomas Duncombe, a key Farrar ally in the Republican Left.

The March 1848 passing of the Treaty of Hull solidified the position of the British Republic against the Kingdom. With a united front, led by Beresford, and the naval power of the Coastal Confederation, a period of relative stability within the “Founding Nine” was established. A number of key institutions were founded in this time, with Attwood at the forefront of constructing a Republic that could survive both a campaign of strife in the South of the country and a peacetime revival of British stature in the world. As Chairman of the General Council, he set about solidifying the institutions already agreed informally between the Republics.

According to his economic adviser, Richard Cobden, the fate of the Revolution would be greatly improved if there was an economic benefit to several powers if the Republic would be victorious. This could be achieved by two methods: a Treaty with European Powers to exchange future control over colonies for support in the conflict, or the establishment of a trading company that would apply free trade to Britain in exchange for naval support.

Attwood, sensed that the removal of the ability to spread the Republic message across the colonies in peacetime would be deeply unpopular with the people, who saw the Revolution as a chance to change the Empire as a whole - in the first few months of the conflict, many of the Republican Press talked of the ‘destiny’ of the Revolution to spread first to the mainland, then to the colonies and finally across the world. This would damage his and the GPPU’s credibility and the credibility on the international stage of the British Republic.

The second option, with a trading route, would prove to be more popular in the General Council and across the Republics. As stockpiles of coal and textiles grew, natural resources and vital supplies were decreasing across the Republics, causing severe pressure on the Revolutionary Leaders. Cotton from America and spices and minerals from the Empire were in short supply, and the Republic badly needed supplies or it would face economic collapse and starvation. Cobden’s idea of a British Republic Trading Company had significant merit, however the economic blockade of the Republic, supported by United Kingdom, the Russian Empire and Prussia, would force Attwood to look for alternative sources of allies.

George Robinson, President of the Coastal States, suggested that his trading bloc along the Netherlands and France would be the perfect starting platform for building a trade network. By April 1848, the Confederation had already began to secure outposts in key ports such as the Hague, and had friendly relations with trading through Belgium to France in clear contempt of the economic blockade. At this time, the Prime Minister of the Netherlands, Johan Rudolph-Thorbecke had sought to liberalise the country, and pointed to Britain as a consequence of maintaining reactionary policies. Attwood sent Farrar to The Hague to negotiate a treaty, with Farrar proposing a common trade area between the Netherlands and Britain, in exchange, Britain would be able to count upon a joint-Naval area between the East Coast of Britain and the Netherlands, patrolled by Dutch and British ships.

Farrar secured the Treaty of The Hague on the 27th April 1848, and secured a permanent Naval and Economic Ally. He followed this up with a trip to France, where he secured a trading treaty in exchange for munitions and access to the Confederation ports. In a similar fashion the French Navy and Coastal States Ships would form a protective barrier for trade along the French West Coast. Farrar was hailed as a hero, securing allies on the continent and supplying the Kingdom with a bloody nose.

The Government in London responded with an attack on the East Coast. Four steam-powered ships were launched up the East Coast from King’s Lynn on 8th May, and Admiral George Elliot launched a bombardment of Grimsby, assuming that French and Dutch ships would not come into aid of the Republic. To their surprise, a coalition force of Confederation, Dutch and French ships launched a counter-attack with 6 ships to defeat the Royal Navy. The defeat was a hammer blow for Gordon-Lennox, who was dismissed on the 1st May 1848 and replaced by a joint rule of the Privy Council.

In response to the attack, Beresford saw it necessary to claim key naval ports along the East-Coast, to open new trading routes with the French and capture Naval Ships along the outposts in King’s Lynn. On 2nd May, he launched an assault to continue along the sea. This surprise assault from the Republican Army Guards caught the Loyalists by surprise, many had been solely guarded by National Front Volunteers, and the port towns of King’s Lynn and Great Yarmouth were liberated after just three days of fighting. The Ports raised the Republican Flag on the 12th May 1848, and their Bureau’s signed the Covenant of the Republic and the Constitution of the Coastal Confederation a day later.

After this, buoyed by victory, the Popular Front moved from Hull to King’s Lynn on 15th May and launched a full scale invasion of much of Norfolk, reaching the border of within eight days and winning control of much of East Anglia. The Republic of East Anglia was proclaimed on the 16th May and headed by former Warden and long-standing member of the GPPU, Frederick Denison Maurice, becoming the 10th Republic.

Internally, the Republic’s had begun the process of rule, and over the month of May, local elections took place in all but East Anglia. At the convention, draft constitutions for the founding nine republics were put into practice. The Republics would be governed by a unicameral assembly, and would have a legislative branch headed by a Chancellor. The Republics would also elect Federal Councillors, who would act on behalf of the Republic’s on a National level and initially provide a level of National Representative government. Attwood, Delane, Farrar, O’Connor and Beresford all declined to stand, instead concentrating at the Convention in Birmingham on constitutional matters for the whole Republic. However, the campaigned across the country and supported candidates.

O’Connor concentrated on furthering candidates aligned to his National Liberal Alliance, winning key victories in Scotland, where Robert Dalglish’s coalition would control of the first Scottish Assembly and Cumbria, where reformer Joseph Ferguson garnered the support of the Cumbrian Council to be elected Chancellor. He also, ironically, won a victory in the Coastal States, where George Robinson who, despite his support for the Treaty of Hull, was a close ally of O’Connor after the Revolution. Farrar campaigned for the Socialist Robert Owen in Wales - irritating O’Connor as he called him an idealist and a socialist, rather than a revolutionary. He also secured the favour of Daniel O’Connell in his re-election as Riarthoir of the Irish Republic, and Thomas Duncombe in Lancashire. Attwood supported Progressive candidates and formed governments in Yorkshire, the Free Cities, and had already secured favour in East Anglia. In the directly elected votes for Federal Councillors, two per-Republic, Liberal factions led by O'Connor won 6 seats (two in Cumbria and one in the Confederation, Yorkshire, Birmingham and Scotland), Socialist led by Farrar in 7 seats (Two in Yorkshire and Wales, and one in Ireland, Scotland and Manchester) and the Attwood coalition in 7 (Manchester, Ireland, Coastal and two in Lancashire and Birmingham)

The Federal Council later re-assembled on May 24th for the re-election of the Chairman of the General Council. Attwood and Fergus O'Connor, along side Delane secured the nominations for the ballot, and over the course of the 25th May voting took place. Attwood had secured 13 votes, O'Connor 6 and Delane 1 (he stated his support for Attwood). Thomas Attwood, in effect, became the first President of the British Republic.

"The Period between April and May in 1848 was a turning point for the Republic. A defeat at King's Lynn, a few more soldiers for the Loyalists and it might well have developed into a stale-mate. An election of Fergus O'Connor and it might well have been a Napoleonic Shift in the Republic's formative years. The Result of May was the stable founding of a vision based on Farrar's principles of mutual assurance and mutual decision making. For better or worse, May set the course for the British Republic as we know it today."

Andrew Marr, 2014

May 1848 meeting of the Republic of Lancashire Assembly, electing Thomas Duncombe, a key Farrar ally in the Republican Left.

The March 1848 passing of the Treaty of Hull solidified the position of the British Republic against the Kingdom. With a united front, led by Beresford, and the naval power of the Coastal Confederation, a period of relative stability within the “Founding Nine” was established. A number of key institutions were founded in this time, with Attwood at the forefront of constructing a Republic that could survive both a campaign of strife in the South of the country and a peacetime revival of British stature in the world. As Chairman of the General Council, he set about solidifying the institutions already agreed informally between the Republics.

According to his economic adviser, Richard Cobden, the fate of the Revolution would be greatly improved if there was an economic benefit to several powers if the Republic would be victorious. This could be achieved by two methods: a Treaty with European Powers to exchange future control over colonies for support in the conflict, or the establishment of a trading company that would apply free trade to Britain in exchange for naval support.

Attwood, sensed that the removal of the ability to spread the Republic message across the colonies in peacetime would be deeply unpopular with the people, who saw the Revolution as a chance to change the Empire as a whole - in the first few months of the conflict, many of the Republican Press talked of the ‘destiny’ of the Revolution to spread first to the mainland, then to the colonies and finally across the world. This would damage his and the GPPU’s credibility and the credibility on the international stage of the British Republic.

The second option, with a trading route, would prove to be more popular in the General Council and across the Republics. As stockpiles of coal and textiles grew, natural resources and vital supplies were decreasing across the Republics, causing severe pressure on the Revolutionary Leaders. Cotton from America and spices and minerals from the Empire were in short supply, and the Republic badly needed supplies or it would face economic collapse and starvation. Cobden’s idea of a British Republic Trading Company had significant merit, however the economic blockade of the Republic, supported by United Kingdom, the Russian Empire and Prussia, would force Attwood to look for alternative sources of allies.

George Robinson, President of the Coastal States, suggested that his trading bloc along the Netherlands and France would be the perfect starting platform for building a trade network. By April 1848, the Confederation had already began to secure outposts in key ports such as the Hague, and had friendly relations with trading through Belgium to France in clear contempt of the economic blockade. At this time, the Prime Minister of the Netherlands, Johan Rudolph-Thorbecke had sought to liberalise the country, and pointed to Britain as a consequence of maintaining reactionary policies. Attwood sent Farrar to The Hague to negotiate a treaty, with Farrar proposing a common trade area between the Netherlands and Britain, in exchange, Britain would be able to count upon a joint-Naval area between the East Coast of Britain and the Netherlands, patrolled by Dutch and British ships.

Farrar secured the Treaty of The Hague on the 27th April 1848, and secured a permanent Naval and Economic Ally. He followed this up with a trip to France, where he secured a trading treaty in exchange for munitions and access to the Confederation ports. In a similar fashion the French Navy and Coastal States Ships would form a protective barrier for trade along the French West Coast. Farrar was hailed as a hero, securing allies on the continent and supplying the Kingdom with a bloody nose.

The Government in London responded with an attack on the East Coast. Four steam-powered ships were launched up the East Coast from King’s Lynn on 8th May, and Admiral George Elliot launched a bombardment of Grimsby, assuming that French and Dutch ships would not come into aid of the Republic. To their surprise, a coalition force of Confederation, Dutch and French ships launched a counter-attack with 6 ships to defeat the Royal Navy. The defeat was a hammer blow for Gordon-Lennox, who was dismissed on the 1st May 1848 and replaced by a joint rule of the Privy Council.

In response to the attack, Beresford saw it necessary to claim key naval ports along the East-Coast, to open new trading routes with the French and capture Naval Ships along the outposts in King’s Lynn. On 2nd May, he launched an assault to continue along the sea. This surprise assault from the Republican Army Guards caught the Loyalists by surprise, many had been solely guarded by National Front Volunteers, and the port towns of King’s Lynn and Great Yarmouth were liberated after just three days of fighting. The Ports raised the Republican Flag on the 12th May 1848, and their Bureau’s signed the Covenant of the Republic and the Constitution of the Coastal Confederation a day later.

After this, buoyed by victory, the Popular Front moved from Hull to King’s Lynn on 15th May and launched a full scale invasion of much of Norfolk, reaching the border of within eight days and winning control of much of East Anglia. The Republic of East Anglia was proclaimed on the 16th May and headed by former Warden and long-standing member of the GPPU, Frederick Denison Maurice, becoming the 10th Republic.

Internally, the Republic’s had begun the process of rule, and over the month of May, local elections took place in all but East Anglia. At the convention, draft constitutions for the founding nine republics were put into practice. The Republics would be governed by a unicameral assembly, and would have a legislative branch headed by a Chancellor. The Republics would also elect Federal Councillors, who would act on behalf of the Republic’s on a National level and initially provide a level of National Representative government. Attwood, Delane, Farrar, O’Connor and Beresford all declined to stand, instead concentrating at the Convention in Birmingham on constitutional matters for the whole Republic. However, the campaigned across the country and supported candidates.

O’Connor concentrated on furthering candidates aligned to his National Liberal Alliance, winning key victories in Scotland, where Robert Dalglish’s coalition would control of the first Scottish Assembly and Cumbria, where reformer Joseph Ferguson garnered the support of the Cumbrian Council to be elected Chancellor. He also, ironically, won a victory in the Coastal States, where George Robinson who, despite his support for the Treaty of Hull, was a close ally of O’Connor after the Revolution. Farrar campaigned for the Socialist Robert Owen in Wales - irritating O’Connor as he called him an idealist and a socialist, rather than a revolutionary. He also secured the favour of Daniel O’Connell in his re-election as Riarthoir of the Irish Republic, and Thomas Duncombe in Lancashire. Attwood supported Progressive candidates and formed governments in Yorkshire, the Free Cities, and had already secured favour in East Anglia. In the directly elected votes for Federal Councillors, two per-Republic, Liberal factions led by O'Connor won 6 seats (two in Cumbria and one in the Confederation, Yorkshire, Birmingham and Scotland), Socialist led by Farrar in 7 seats (Two in Yorkshire and Wales, and one in Ireland, Scotland and Manchester) and the Attwood coalition in 7 (Manchester, Ireland, Coastal and two in Lancashire and Birmingham)

The Federal Council later re-assembled on May 24th for the re-election of the Chairman of the General Council. Attwood and Fergus O'Connor, along side Delane secured the nominations for the ballot, and over the course of the 25th May voting took place. Attwood had secured 13 votes, O'Connor 6 and Delane 1 (he stated his support for Attwood). Thomas Attwood, in effect, became the first President of the British Republic.

Last edited:

Chapter 11: Ghost Colonies (Part 1)

"As the world reacted to the falling of the United Kingdom, the territories who reacted the slowest and with the least unity were the British Colonies - the question of loyalty, to the queen or to their homeland, was pertinent and the answers not always the same"

John Kerry, Britain: A Republic from the Ruins, 1996

The Bristol Uprising begins in earnest, 1848.

As the Republic celebrated victories on the East Coast, they continued their push to re-unify the whole of East Anglia throughout June. Suffolk was invaded on 12th June, with Ipswich being reached within a day, and Kent and the South Coast was reached on the 15th. The Republic now controlled territory from the Northern most tip of the country to the South Coast. On the 18th June, an uprising turned into a mass mutiny in the Port town of Bristol, and British Republican Troops crossed in fishing boats from Cardiff to support the rebellion. Popular Front fighters moved across the border and liberated Gloucestershire and Bristol on 21st June, and the Republic of Severn was declared later that day - the Republican flag and the flag of the new republic raised in Bristol, and the 11th Republic accepted into the United States of the British Republic.

This sparked fear amongst Ancien Regime in parts of the North, who flocked to the Northern tip of Britain to the Port Town of Cromarty Firth, where a fleet was arranged to carry refugees to Shetland. Six-thousand retreated, over half lost at sea in the treacherous conditions of the North Atlantic. They arrived on the Island on 18th June, where they remained for just over 6 weeks, when a message from the mainland informed them of a rump Loyalist state formed in the Irish Province of Ulster. They seized native’s ships and began to prepare to set sail.

They reached Larne with their munitions, ransacked from military and naval bases on Shetland, and landed, ready to join the revolution. However, instead of finding a Loyalist safe-haven, they round the Republic of Ireland in dominance. The Information was false - and provided to them by Republican forces to allow them to liberate Shetland.

Instead of surrendering, the loyalists began to fight their way down, recruiting more to their armies over a seven day period and forcing the Republicans out of both Antrim and Down. As they entered Belfast, they declared the ‘Northern Free State’ and swore an oath of loyalty to the crown and to defend the honour of the British Empire. As their men, who had reached 18,000 through recruitment in the mostly de-militarised loyalist regions in the North-East, barricaded themselves along the border and began controlling the roads, their plight brought the attention of the Government in London. They sent a shipment of munitions and supplies to the Isle of Man, where the Royal Navy was basing the majority of its attacks on Republican Ports of Liverpool and Holyhead. This was then sent up to the Free State, who now had weapons, men and supplies to last them about 6-8 months.

The Republicans responded with a full scale attack on the territory. Known loyalists were rounded up to prevent further insurrection in Ireland. The fight quickly turned into a stalemate, and defensive positions were dug on county borders. The Irish Revolutionary Wars had begun. The Free State drafted the ‘Free State Covenant’ - which declared the commitment to defend their territory until the end. It was signed by 18,000 men, women and children, most of whom signed in blood.

British Republican Army's Irish Division attempts to defeat the Loyalist insurgency in Ulster

Meanwhile, in the colonies, information on the growing conflict was sketchy and vague at best. In Australia, administrative centres quizzed travelling merchants as they entered the territories about the situation in Britain. The sailors said that the motherland was fine - as it was, when they set off in December the previous year. Still, rumours of an insurrection spread quickly to colonialists, who feared for their families lives and that either the new government or foreign powers would intervene and disturb their indirect rule. In two colonies however, Information was much more free-flowing. Dutch and French sailors received with British Republic representatives had a much shorter travel time of about 5 to 6 days, allowing a more up to date flow of news. As the Representatives went to negotiate with the United States, news reached Quebec and Newfoundland that a Revolution had taken full-hold on much of Britain.

In St John, the Revolutionaries of the First Newfoundland War began to rearm, and on the 9th July, launched a full-scale uprising, taking control of the province and expelling Colonial Troops. The Colonial Administration appealed for support to control the takeover, but received no munitions of information back from London. The Republic’s fortified and dug defensive positions to protect their territory.

As news reached Washington of the developments, a hasty Treaty was drafted between the Republic and the United States. Anti-British sentiment had been growing in the region, and the President, James Polk, was keen to establish formal relations with the new regime. In return for free access to Ports on the West Coast of Ireland and England, they would recognize and provide military support for the new regime. The delegates from Britain also negotiated support for the upstart Republics in the Treaty of Washington. They assured Washington that control over trading outposts was in the Republics hands, with the exception of Southampton, and support from the Empire take months to arrive. The British Empire, simply, had better things to do. Coastal Confederation ships had in May and June launched convoys which cut off access to British ports on the mainland, with French support. Polk accepted, and sent US munitions into Quebec and Newfoundland to fortify the positions and support the Republics.

Across the Colonies, slowly communications dried up. Administrations were left without direction, and took controlling matters into their own hands. As news of the Revolution reached their shores, they debated what side to pick.

"As the world reacted to the falling of the United Kingdom, the territories who reacted the slowest and with the least unity were the British Colonies - the question of loyalty, to the queen or to their homeland, was pertinent and the answers not always the same"

John Kerry, Britain: A Republic from the Ruins, 1996

The Bristol Uprising begins in earnest, 1848.

As the Republic celebrated victories on the East Coast, they continued their push to re-unify the whole of East Anglia throughout June. Suffolk was invaded on 12th June, with Ipswich being reached within a day, and Kent and the South Coast was reached on the 15th. The Republic now controlled territory from the Northern most tip of the country to the South Coast. On the 18th June, an uprising turned into a mass mutiny in the Port town of Bristol, and British Republican Troops crossed in fishing boats from Cardiff to support the rebellion. Popular Front fighters moved across the border and liberated Gloucestershire and Bristol on 21st June, and the Republic of Severn was declared later that day - the Republican flag and the flag of the new republic raised in Bristol, and the 11th Republic accepted into the United States of the British Republic.

This sparked fear amongst Ancien Regime in parts of the North, who flocked to the Northern tip of Britain to the Port Town of Cromarty Firth, where a fleet was arranged to carry refugees to Shetland. Six-thousand retreated, over half lost at sea in the treacherous conditions of the North Atlantic. They arrived on the Island on 18th June, where they remained for just over 6 weeks, when a message from the mainland informed them of a rump Loyalist state formed in the Irish Province of Ulster. They seized native’s ships and began to prepare to set sail.

They reached Larne with their munitions, ransacked from military and naval bases on Shetland, and landed, ready to join the revolution. However, instead of finding a Loyalist safe-haven, they round the Republic of Ireland in dominance. The Information was false - and provided to them by Republican forces to allow them to liberate Shetland.

Instead of surrendering, the loyalists began to fight their way down, recruiting more to their armies over a seven day period and forcing the Republicans out of both Antrim and Down. As they entered Belfast, they declared the ‘Northern Free State’ and swore an oath of loyalty to the crown and to defend the honour of the British Empire. As their men, who had reached 18,000 through recruitment in the mostly de-militarised loyalist regions in the North-East, barricaded themselves along the border and began controlling the roads, their plight brought the attention of the Government in London. They sent a shipment of munitions and supplies to the Isle of Man, where the Royal Navy was basing the majority of its attacks on Republican Ports of Liverpool and Holyhead. This was then sent up to the Free State, who now had weapons, men and supplies to last them about 6-8 months.

The Republicans responded with a full scale attack on the territory. Known loyalists were rounded up to prevent further insurrection in Ireland. The fight quickly turned into a stalemate, and defensive positions were dug on county borders. The Irish Revolutionary Wars had begun. The Free State drafted the ‘Free State Covenant’ - which declared the commitment to defend their territory until the end. It was signed by 18,000 men, women and children, most of whom signed in blood.

British Republican Army's Irish Division attempts to defeat the Loyalist insurgency in Ulster

Meanwhile, in the colonies, information on the growing conflict was sketchy and vague at best. In Australia, administrative centres quizzed travelling merchants as they entered the territories about the situation in Britain. The sailors said that the motherland was fine - as it was, when they set off in December the previous year. Still, rumours of an insurrection spread quickly to colonialists, who feared for their families lives and that either the new government or foreign powers would intervene and disturb their indirect rule. In two colonies however, Information was much more free-flowing. Dutch and French sailors received with British Republic representatives had a much shorter travel time of about 5 to 6 days, allowing a more up to date flow of news. As the Representatives went to negotiate with the United States, news reached Quebec and Newfoundland that a Revolution had taken full-hold on much of Britain.

In St John, the Revolutionaries of the First Newfoundland War began to rearm, and on the 9th July, launched a full-scale uprising, taking control of the province and expelling Colonial Troops. The Colonial Administration appealed for support to control the takeover, but received no munitions of information back from London. The Republic’s fortified and dug defensive positions to protect their territory.

As news reached Washington of the developments, a hasty Treaty was drafted between the Republic and the United States. Anti-British sentiment had been growing in the region, and the President, James Polk, was keen to establish formal relations with the new regime. In return for free access to Ports on the West Coast of Ireland and England, they would recognize and provide military support for the new regime. The delegates from Britain also negotiated support for the upstart Republics in the Treaty of Washington. They assured Washington that control over trading outposts was in the Republics hands, with the exception of Southampton, and support from the Empire take months to arrive. The British Empire, simply, had better things to do. Coastal Confederation ships had in May and June launched convoys which cut off access to British ports on the mainland, with French support. Polk accepted, and sent US munitions into Quebec and Newfoundland to fortify the positions and support the Republics.

Across the Colonies, slowly communications dried up. Administrations were left without direction, and took controlling matters into their own hands. As news of the Revolution reached their shores, they debated what side to pick.

Meanwhile, in the colonies, information on the growing conflict was sketchy and vague at best. In Australia, administrative centres quizzed travelling merchants as they entered the territories about the situation in Britain. The sailors said that the motherland was fine - as it was, when they set off in December the previous year. Still, rumours of an insurrection spread quickly to colonialists, who feared for their families lives and that either the new government or foreign powers would intervene and disturb their indirect rule. In two colonies however, Information was much more free-flowing. Dutch and French sailors received with British Republic representatives had a much shorter travel time of about 5 to 6 days, allowing a more up to date flow of news. As the Representatives went to negotiate with the United States, news reached Quebec and Newfoundland that a Revolution had taken full-hold on much of Britain.

In St John, the Revolutionaries of the First Newfoundland War began to rearm, and on the 9th July, launched a full-scale uprising, taking control of the province and expelling Colonial Troops. The Colonial Administration appealed for support to control the takeover, but received no munitions of information back from London. The Republic’s fortified and dug defensive positions to protect their territory.

As news reached Washington of the developments, a hasty Treaty was drafted between the Republic and the United States. Anti-British sentiment had been growing in the region, and the President, James Polk, was keen to establish formal relations with the new regime. In return for free access to Ports on the West Coast of Ireland and England, they would recognize and provide military support for the new regime. The delegates from Britain also negotiated support for the upstart Republics in the Treaty of Washington. They assured Washington that control over trading outposts was in the Republics hands, with the exception of Southampton, and support from the Empire take months to arrive. The British Empire, simply, had better things to do. Coastal Confederation ships had in May and June launched convoys which cut off access to British ports on the mainland, with French support. Polk accepted, and sent US munitions into Quebec and Newfoundland to fortify the positions and support the Republics.

Across the Colonies, slowly communications dried up. Administrations were left without direction, and took controlling matters into their own hands. As news of the Revolution reached their shores, they debated what side to pick.

With Great Britain in chaos at this time, it seems likely that the British India Company will fall from an alternate Sepoy Rebellion that is successful. The expulsion of colonial rule will result in the in Subcontinent descending into infighting between state-lets. while the colonial holdings of South East Asia will get conquered by ambitious regional or colonial powers.

The Cape Colony will see the expansion come to a grinding halt from the loss of troops being supplied by the homeland. meaning that the Natal Republic survives and could try to retake the the Cape with the Boers.

The Colony of New South Wales would probably stay loyal to the crown, and probably become the Kingdom of Australasia in the future.

The East India Company may just try going into business for itself. I don't know how much actual loyalty it felt to the United Kingdom, Crown or otherwise.

At this point in time, can the EIC survive on it's own? Maybe trading with, well, anyone and everyone? I don't know the state of it's finances at this point in time.

At this point in time, can the EIC survive on it's own? Maybe trading with, well, anyone and everyone? I don't know the state of it's finances at this point in time.

The East India Company may just try going into business for itself. I don't know how much actual loyalty it felt to the United Kingdom, Crown or otherwise.

At this point in time, can the EIC survive on it's own? Maybe trading with, well, anyone and everyone? I don't know the state of it's finances at this point in time.

That is what I suspect as well. Though I doubt it will last given how this won't immediate remove the causes that led to the Indian rebellion in OTL. So can they put it down like OTL without Great Britain to send reinforcements.

That is what I suspect as well. Though I doubt it will last given how this won't immediate remove the causes that led to the Indian rebellion in OTL. So can they put it down like OTL without Great Britain to send reinforcements.

However, it's also far enough away from from the OTL Sepoy Rebellion that it can be butterflied away. I don't know how deep the structural causes of the Sepoy Rebellion and how much of it was the spread of the rumour about the Pork Fat bullet cases.

Share: