There is indeed more to come. This next one will likely be the USA and will be the final one for the 1924-1931 series.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Red Sun Rising: The Reverse-Russo-Japanese War

- Thread starter Forbiddenparadise64

- Start date

Ooh!!!There is indeed more to come. This next one will likely be the USA and will be the final one for the 1924-1931 series.

Now some detailed resources on the 20s era US would be good for it. Something more in depth than Wikipedia if possible.Viva espana monarchia!

USA (1924-1931)

Carlos Kennedy, Revolution, Evolution and Struggle, A History of the United States of America, 2013, pp.213-215

While the rest of the world was a mixed bag following the Great War, the United States had remained neutral, and so never suffered the way other nations did from economic shortages. Nevertheless, America went through major difficulties of its own during this time, primarily economic or influential in concerns. With there former colony of the Phillipines independent, American imperialism had certainly lowered thanks to Bryan's presidency, but this would be temporary indeed. The need to restore American influence in Latin America was important too. When Bryan needed to leave the White House, a new political situation began to arise.

In the Deep South, racial tensions were as high as ever. African Americans living in the region continued to suffer at the hands of Klansmen and other racist groups. In addition to traditional racists, groups influenced by Paraguay and France were starting to gain track. In Louisiana, Social Action inspired groups began to appear, hoping to merge American nationalist values and such with the authoritarian economics and a strong leadership that democracy was not providing. Even here though, such groups remained a minority, though a very vocal one. Though Jim Crow laws were still in effect, even among the White populace there was growing opposition here. Protesters such as the progressively political youth Huey Long and African American Jazz player John Wickham [1] brought about considerable influence in their respective ethnic neighbourhoods hoping to repeal segregation and improve financial distributions within the areas. Communist parties were naturally very small, as the ideology that had taken over Japan was certainly at odds with what the American people saw as their way of life. While not as common in the Deep South as on the west coast, increased xenophobia and suspicion was drawn on people from Asia, arguing that their egalitarian philosophy could cause a revolution in the USA. Despite the actual unlikely hood of such aims, for many different reasons, this era frequently promoted such views in unofficial terms.

Further up north, in the mid-west, problems arose from the reduction of trade with Western Europe, as it was increasingly difficult to be involved wit the French, who were resentful of the US not intervening in the Great War, even if by that point the French were already on the losing sife. Perhaps in a world where the French had performed better, the USA could have desired to intervene more and prevent German victory. But regardless, the lack of ability to sell crops led to inflation.

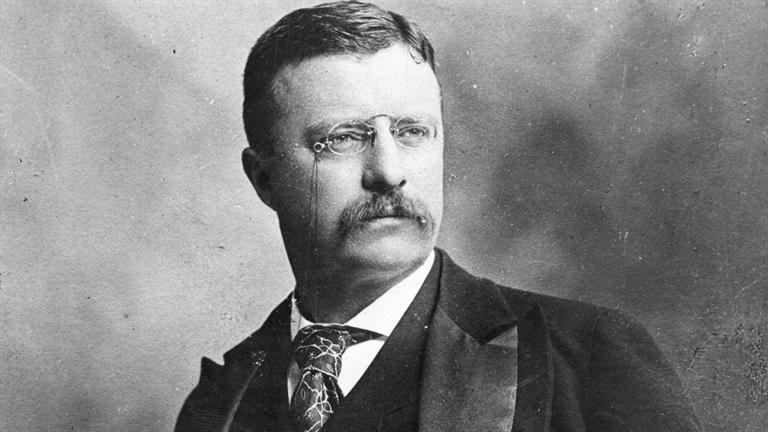

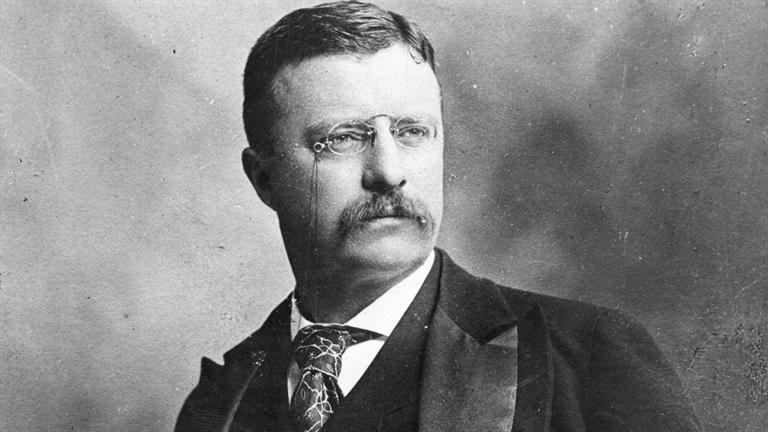

The return of the legendary 'Teddy' Roosevelt to the political stage was one of the defining moments of the early twentieth century, leaning the Republican Party towards more progressive viewpoints and away from Bryan's conservatism.

The 1924 election saw the Republicans ultimately take the main position of power, lead by a former sworn in president, Theodore 'Teddy' Roosevelt[2]. With progressive but right-orientated politics, the Republican party made headway in organising the nation towards a new direction, one more open to trade with the new orders of Europe and Asia. Despite the president's substantial age, he was in a physically healthy position and hoped that this would not undermine his career, while not wishing to simply copy opportunities he had gotten in the past. Roosevelt's experienced helped him deal with the existent bureaucracy that was present in Washington and prepare the global financial sphere for what was to come.

With somewhat deteriorating relationships with the Japanese following Bryan's descension from the Presidency, Roosevelt instead turned his head to the physically largest power in East Asia, the Republic of China. With Sun's declining health, the mentality of a fledgling democracy in Asia provided American interests with a major ace in the hole, to compensate the loss of the unstable Philippines to the south. Direct colonialism was not an option, particularly with an aggressive Russia to the north and west, but business interests were a definite possibility. The Shanghai Company was being set up in by young businessman Harold Harding in 1927 with permission from president Roosevelt for corporate interests. Goods would be gathered for resources from China and be manufactured around the world, which helped the USA become one of hte world's top manufacturers at this time, while allowing Chinese money to flow as well.

In Latin America, the rise of fascism in Paraguay in 1925 and later, French backed juntas in Chile, Colombia and Peru led to a destabilisation of power in the region as American influence became increasingly marginalised. The otherwise isolationist USA came to see this as a threat to their interests in the region, hoping to compensate by funding the rival governments in Brazil, Bolivia and Argentina, all in the name of preserving the American model of democracy in the region. The militaries were given funding, but the embassies decided it was best to keep the democratically elected government in a position of real power rather than allow governments resembling fascism to take power. Reluctantly, this sometimes involved funding socialist groups in the population who happened to be anti-fascist, which was met with significant resistance back home, even if these groups were not communist. Japanese attempts at promoting local communist parties also fell through in the democratic nations due to fears of dictatorship, though many of the poor did indeed sympathise with the message. Surprisingly, the anarchism ideology that had been present for years in Nauru, now under the leadership of Sakae Osugi following the death of founder Kotuko in 1926 [3], was spreading within the populations of certain countries. The deep jungles of the Amazon began to be breeding ground for anarchist idealists hoping to set up free territories under a utopian ideal, while similar ideas spread into the destabilising Bolivia, which was stuck between pro-French and pro-American factions, along with multiple smaller ones who desired neither. The situation in Bolivia would be one of the main points of contention in the Second Great War to come, but for now, the US focused their attention elsewhere, unaware of the problem.

The American navy particularly needed upgrading in its equipment, once President Roosevelt realised that without a war to prompt technological progress, that American naval ships were significantly behind their pears in the British, French and German Empires. President Roosevelt significantly increased the military's budget in order to protect American neutrality from the increasingly ambitious Alliance and Entente, while upholding influence in Latin America. With the USS Washington commissioned in 1928, the most largest and most heavily armed battleship in history up to that point, it was certainly a point indicating the rise of the USA as a major global power, were it not clear enough already. The British ships passing from Canada and the Bahamas seemed weaker following the advent of Washington, and Britain felt intimidated by this new weapon, hoping to construct an even more impressive naval ship of its own, the HMS Churchill, named after late politician Randolph Churchill. Neither nation had any intention of creating political tensions between the other though, so interests were made sure to remain relatively stable.

The 1928 election saw Roosevelt lose the election to Democrat Al Smith over Smith's promises to improve regulation of substances such as alcohol, which had neared being prohibited by many conservative politicians. Smith's Catholicism however found controversy within many of America's evangelical protestants, who feared a Papist takeover, and some of these offended Italian Americans present. One particularly disastrous impact of this was the 4th of July 1929 bombing of the Italian embassy in Washington, leading to the deaths of four and injuries to thirteen others. Smith did what he could in his 'Homecoming' speech three days later to mend relations with the Italian government, and made investigations to find and incarcerate those responsible. Only three out of the five responsible were caught though, and all were given the death sentence for treason, with their sentences being carried out over the next three years. Catholic Americans on the other hand found themselves prosperous under Smith's presidency, as did those who feared the overly conservative elements of society, such as many African Americans.

As a new decade began, the United States was positioning itself as a major global power, despite not being involved in the Great War of Europe. This showed that it did not take great armies and brute force to dominate the economy, but diplomacy and prosperity as well. Thus the United States did not suffer the way much of Europe did during the late 1920s.

[1] born after the POD and so a new person.

[2] managed to avoid his otl decline in health here and managed to beat Warren G. Harding as the Republican nominee as a result.

[3] This resulted in the previously atheistic anarchism evolving towards a spiritualist, even deist direction. Due to a lack of central organisation, the influence of religious anarchist groups such as Tolstoyists became noted, particularly in Latin American communes.

While the rest of the world was a mixed bag following the Great War, the United States had remained neutral, and so never suffered the way other nations did from economic shortages. Nevertheless, America went through major difficulties of its own during this time, primarily economic or influential in concerns. With there former colony of the Phillipines independent, American imperialism had certainly lowered thanks to Bryan's presidency, but this would be temporary indeed. The need to restore American influence in Latin America was important too. When Bryan needed to leave the White House, a new political situation began to arise.

In the Deep South, racial tensions were as high as ever. African Americans living in the region continued to suffer at the hands of Klansmen and other racist groups. In addition to traditional racists, groups influenced by Paraguay and France were starting to gain track. In Louisiana, Social Action inspired groups began to appear, hoping to merge American nationalist values and such with the authoritarian economics and a strong leadership that democracy was not providing. Even here though, such groups remained a minority, though a very vocal one. Though Jim Crow laws were still in effect, even among the White populace there was growing opposition here. Protesters such as the progressively political youth Huey Long and African American Jazz player John Wickham [1] brought about considerable influence in their respective ethnic neighbourhoods hoping to repeal segregation and improve financial distributions within the areas. Communist parties were naturally very small, as the ideology that had taken over Japan was certainly at odds with what the American people saw as their way of life. While not as common in the Deep South as on the west coast, increased xenophobia and suspicion was drawn on people from Asia, arguing that their egalitarian philosophy could cause a revolution in the USA. Despite the actual unlikely hood of such aims, for many different reasons, this era frequently promoted such views in unofficial terms.

Further up north, in the mid-west, problems arose from the reduction of trade with Western Europe, as it was increasingly difficult to be involved wit the French, who were resentful of the US not intervening in the Great War, even if by that point the French were already on the losing sife. Perhaps in a world where the French had performed better, the USA could have desired to intervene more and prevent German victory. But regardless, the lack of ability to sell crops led to inflation.

The return of the legendary 'Teddy' Roosevelt to the political stage was one of the defining moments of the early twentieth century, leaning the Republican Party towards more progressive viewpoints and away from Bryan's conservatism.

The 1924 election saw the Republicans ultimately take the main position of power, lead by a former sworn in president, Theodore 'Teddy' Roosevelt[2]. With progressive but right-orientated politics, the Republican party made headway in organising the nation towards a new direction, one more open to trade with the new orders of Europe and Asia. Despite the president's substantial age, he was in a physically healthy position and hoped that this would not undermine his career, while not wishing to simply copy opportunities he had gotten in the past. Roosevelt's experienced helped him deal with the existent bureaucracy that was present in Washington and prepare the global financial sphere for what was to come.

With somewhat deteriorating relationships with the Japanese following Bryan's descension from the Presidency, Roosevelt instead turned his head to the physically largest power in East Asia, the Republic of China. With Sun's declining health, the mentality of a fledgling democracy in Asia provided American interests with a major ace in the hole, to compensate the loss of the unstable Philippines to the south. Direct colonialism was not an option, particularly with an aggressive Russia to the north and west, but business interests were a definite possibility. The Shanghai Company was being set up in by young businessman Harold Harding in 1927 with permission from president Roosevelt for corporate interests. Goods would be gathered for resources from China and be manufactured around the world, which helped the USA become one of hte world's top manufacturers at this time, while allowing Chinese money to flow as well.

In Latin America, the rise of fascism in Paraguay in 1925 and later, French backed juntas in Chile, Colombia and Peru led to a destabilisation of power in the region as American influence became increasingly marginalised. The otherwise isolationist USA came to see this as a threat to their interests in the region, hoping to compensate by funding the rival governments in Brazil, Bolivia and Argentina, all in the name of preserving the American model of democracy in the region. The militaries were given funding, but the embassies decided it was best to keep the democratically elected government in a position of real power rather than allow governments resembling fascism to take power. Reluctantly, this sometimes involved funding socialist groups in the population who happened to be anti-fascist, which was met with significant resistance back home, even if these groups were not communist. Japanese attempts at promoting local communist parties also fell through in the democratic nations due to fears of dictatorship, though many of the poor did indeed sympathise with the message. Surprisingly, the anarchism ideology that had been present for years in Nauru, now under the leadership of Sakae Osugi following the death of founder Kotuko in 1926 [3], was spreading within the populations of certain countries. The deep jungles of the Amazon began to be breeding ground for anarchist idealists hoping to set up free territories under a utopian ideal, while similar ideas spread into the destabilising Bolivia, which was stuck between pro-French and pro-American factions, along with multiple smaller ones who desired neither. The situation in Bolivia would be one of the main points of contention in the Second Great War to come, but for now, the US focused their attention elsewhere, unaware of the problem.

The American navy particularly needed upgrading in its equipment, once President Roosevelt realised that without a war to prompt technological progress, that American naval ships were significantly behind their pears in the British, French and German Empires. President Roosevelt significantly increased the military's budget in order to protect American neutrality from the increasingly ambitious Alliance and Entente, while upholding influence in Latin America. With the USS Washington commissioned in 1928, the most largest and most heavily armed battleship in history up to that point, it was certainly a point indicating the rise of the USA as a major global power, were it not clear enough already. The British ships passing from Canada and the Bahamas seemed weaker following the advent of Washington, and Britain felt intimidated by this new weapon, hoping to construct an even more impressive naval ship of its own, the HMS Churchill, named after late politician Randolph Churchill. Neither nation had any intention of creating political tensions between the other though, so interests were made sure to remain relatively stable.

The 1928 election saw Roosevelt lose the election to Democrat Al Smith over Smith's promises to improve regulation of substances such as alcohol, which had neared being prohibited by many conservative politicians. Smith's Catholicism however found controversy within many of America's evangelical protestants, who feared a Papist takeover, and some of these offended Italian Americans present. One particularly disastrous impact of this was the 4th of July 1929 bombing of the Italian embassy in Washington, leading to the deaths of four and injuries to thirteen others. Smith did what he could in his 'Homecoming' speech three days later to mend relations with the Italian government, and made investigations to find and incarcerate those responsible. Only three out of the five responsible were caught though, and all were given the death sentence for treason, with their sentences being carried out over the next three years. Catholic Americans on the other hand found themselves prosperous under Smith's presidency, as did those who feared the overly conservative elements of society, such as many African Americans.

As a new decade began, the United States was positioning itself as a major global power, despite not being involved in the Great War of Europe. This showed that it did not take great armies and brute force to dominate the economy, but diplomacy and prosperity as well. Thus the United States did not suffer the way much of Europe did during the late 1920s.

[1] born after the POD and so a new person.

[2] managed to avoid his otl decline in health here and managed to beat Warren G. Harding as the Republican nominee as a result.

[3] This resulted in the previously atheistic anarchism evolving towards a spiritualist, even deist direction. Due to a lack of central organisation, the influence of religious anarchist groups such as Tolstoyists became noted, particularly in Latin American communes.

Last edited:

1932 map.

Here's the beginning of 1932 in Map form.

The descriptions describe much of the changes, but theres some more minor ones too.

The descriptions describe much of the changes, but theres some more minor ones too.

- Order is collapsing in Bolivia as the undemocratic Rodriguez government, a military dictatorship faces a coalition of opponents hoping for reforms, or at the very least the end of his regime. However, it is clear many of those in this coalition merely want a change in management in their favour.

- Along with these rebels come generic warlords out for simple power, and also radical socialists. Anarchists in particular thrive towards the north of the country, where something resembling agrarian Tolstoyism is taking root, under influence from the Free Territory of Nauru.

- Cesar uses the Bolivian Civil War as an oppurtunity to occupy the coveted lands he held claims on. None of the other South American nations, bar Peru and Colombia recognise this.

- The Hashemites, with heavy British funding, finally triumph over the unbacked Saudis. Arabia is now a British protectorate in all but name, its independence a mere rubber stamp.

- Italy maintains its claims on Jugoslavian Dalmatia, though the latter's radical Pan-Slavic nationalists, under Russian funding, wish to turn the tables on the Italians.

- The Phillipinos crush the Mindanaon insurrection, unfortunately resulting in pogroms against Muslims living in the north of the country. Drained by the war, their military is left weaker, and so the imperialistic eyes of a certain European nation is starting to turn their way.

- Talks of unification between Poland, Slovakia and Ruthenia into a federation similar to Jugoslavia are considered, though the Germans are very reluctant about allowing this, given the risks it may bring.

Last edited:

France (1932-1937)

Larry Baldwin, The French Gamble, 2011

With Rocque's Social Action regime in full swing, France's reascension as a global power seemed inevitable. The campaign to take back the lands that had been taken from France was one of propaganda to begin with, but it would not remain this way forever. Increased agitation by French-speaking peoples across Europe provided an indirect call to arms for the French people. Rocque argued that Germany's repeated crushing of French spirit would need to be readdressed once and for all, to make sure Germany could never again oppress the French peoples of Alsace-Lorraine, Nancy and Luxembourg. The new French Empire would take back all the lands that Napoleon had once acquired, and perhaps even more.

Unlike the Napoleon of old, Rocque did not have any desire for war with Russia, given that Wrangel's regime was similar both ideologically and in ambitions, with neither of their goals known to have overlapped with one another. While some in Croix's cabinet such as the notorious Jacques Doriot desired all of non-Russian Europe, including places as far as Poland and the Ukraine to be within the French sphere of influence, Rocque was able to guide the rest of Social Action into a conhesive order. Doriot's more radical take on fascism, more akin to the Turkomen regime than to Rocque's leadership became a problematic element, and so the Croix, the Social Action regime's secret police, ultimately took action. In September 1932, a wave of attacks and arrests were made around Paris, with hundreds arrested or outright killed. Among those arrested were Doriot himself, Xavier Vallat

, who had been proving increasingly restless in his own attempts for power (1), and over 200 others who were suspected of being 'those out to undermine the peace'. Mock trials were held and executions were taken place, with the worst traitors being given public deaths in Paris square, in an ironic homage to the French Revolution.

Emperor Louis Napoleon held little power over the French nation, but his influence was certainly profound. As a descendent of Napoleon Bonaparte himself, the founder of the First French Empire, he granted Social Action the legitimacy it needed to be secured as a significant government. The minister of propaganda Francois Coty claimed often in public speeches that Louis was bringing the nation under the unity of his ancestors, but the truth of these claims is at best dubious. Under force from Rocque's advisers, he signed approvals for whichever actions Rocque chose to implement over the nation. Following the regime's dismantling, the former emperor told us "I was hardly an emperor at all. Just a puppet, with Francois [Rocque] pulling the strings. It was honestly some of the worst days of my life." But to take a risk for the French nation, Rocque played God over him. Even his fellow monarchists found such behaviour repulsive. The action that would need to be taken for the new empire was to continue purges of disloyal elements, and increase propaganda production to rally fears of the nation upon the Germans, and soon the British as ties with them became increasingly severed as Britain went towards isolation.

The spring of 1933 proved to be an eventful and helpful year for the regime. With the situation in the eastern satellites of Germany deteriorating, France pressed its advantage with the already reduced demilitarised zone. With German forces repressing rebellion in Poland and the Ukraine (who also started to fight each other), Rocque seized his chance and marched east. The zone was fully reoccurred in a week, with only minor resistance present. For the Germans did not allow demilitarised French to participate in elections, they were at the mercy of the German military. Now though, the French military moved in right up to the German border, with Rocque and Social Action setting his eyes upon the lost provinces of Nancy, Alsace Lorraine and Luxembourg, as well as the industrially developed Saarland. With order restored here, the unification of the French people there with their motherland proved a great boost of morale. Yet there remained French speaking peoples outside the motherland too-not just in Germany and Spain, but also in such places as Belgium and Switzerland. These places too would require 'liberation' in Rocque's eyes, and the non-Francophone living there would be vassalised and granted chances to convert to French language, culture and even racial characteristics. This would certainly be carried on in France's North African colonies such as Algeria and Tunisia, as increased amounts of settlers poured into the regions. The living space for French people needed to grow, after all. At least in Rocque's eyes.

With militarisation under way, France's new economy was once again on the rise. The military was an area particulary emphasised under the regime, with the building of a new, technologically up to date air force was considered essential. The army and navy were already quite sizeable, so the only necessary changes were purging the officer corps to ensure loyalty to Social Action and its principles. As the year progresses, the Rocque dictatorship begin its preparations for the Second Great War. The French military was not ready to wage war against the nation's of Germany and Spain, who took its land, or even against the smaller Belgians and Swiss, so they needed a weaker target to start with and learn from.

The Recolonisation that occurred was the first major step in France's territorial expansion. With Cambodia disorganised and outside Japan's new sattelites states, it was left vulnerable to attack. In an era where colonialism was a significant element, Rocque's regime set apart the first step in reclaiming the lost Indochina. Mobilising a fleet in the thousands, Social Action began the reclamation of Cambodia- it's own Reconquista in the eyes of the world.

In December 1933, the first landings were made. While outnumbered by natives, the French possessed superior technology, discipline and training to the villagers and local feudal armies present. The events mirrored the first colonisation of Cambodia, only these were more intense in their form. The local communities quickly bent their knees in submission to their old overlords, only these were more aggressive and less tolerant of rebellion, not wishing to repeat the mistakes of their ancestors. Little Vietnam became annexed by its larger neighbour. The Free territory to the south-east once again geared itself as its imperialist neighbour fell, with thousands preparing to flee once more to a new land. The anarchists of Nauru as well began to prepare fleeing as the Japanese went to reclaim their islands. Within ten weeks, Cambodia had fallen once more to the new French military. Tens of thousands of anarchists fled these free territories once again. A new anarchic zone was developing within the failed state of Bolivia, and so this was the destination of the anarchist experiment. In the meantime, the French reclamation of Indochina had begun. It would be years before the second phase began, with the other nations as Japanese satellites, but it would begin again.

Around 1934, the la Croix government went into negotiations regarding a period of instability in Switzerland. With the economic declines across the world, Switzerland was hit particularly hard during the beginning of the 1930s, with many investments in that nation being withdrawn, their sources of income declined alongside the nations they supplied, and so living standards and wages started to decrease. In this new unstable era, old tensions rose again.

Following the assassination on the 3rd of November 1932 of Geneva's Président du Conseil administratif, Gustav Ador by a German-speaking nationalist of a local fringe protestant Pan-German group, there were increasing tensions between the different cultural groups within Switzerland. After this, tensions that had been dormant since the Sonderbund of the 19th century rose once more between German and French populations, as well as between Catholics and Protestants. With this happening, the country's political climate began to polarise away from the standard party models which had dominated before. With the government in Bern favouring the German majority a few too many times, Pan-French groups in Geneva and it's respective area campaigned increasingly to separate from Switzerland, also hoping to get past the government's seperation of Church and State. Rocque welcomed such ideas, and soon began incorporating and encouraging such separatist movements in the country. His creation of a "Pan-romantic" identity for the French people would help glue the French race together against the oppressive Germanics who had repeatedly put them down for centuries in Germany and in England. With a stagnating economy and racial tensions, the previously stable democracy in that nation began to deteriorate.

Germany and the United Kingdom both independently backed the Swiss government, for despite the hardships, many still had significant investments in that country, as a neutral area and place of stability within an increasingly hostile continent. While both normally at odds with one another, the fires stoked by the fascist French and Russians were driving them closer together, something that would eventually spell the downfall of this ideology and both empires. Along with the Turkish, Paraguay, Peru and Colombia, the move towards extreme nationalism was set to change the course of history.

But Swiss partisans soon put an end to this, as the Christmas Massacre took place. A group of French-speaking protesters spoke out against the German favouritism and cultural supremacy present in the neutral nation. Though peaceful, the conservative, unstable Federal Council had none of it, and due to miscommunication, opened fire on the protesters. Riots broke out, and even many international benefactors condemned the act. Seitzerland's status of neutrality was now compromised.

The French members of te council fell out from this, and the council faced major upheaval as a result of the disaster. To make matters worse, French nationalists grew in power and influence, using the massacre to justify rebellion and soon secession. In January 1935, the French parts of Switzerland finally broke off from the main republic, forming the short-lived National Republic of Greater Geneva, focussed on the French speaking majority there. Quick diplomacy by Croix and his followers brought this fledgling nation under sway, and on the 3rd of February 1935, Geneva was once more annexed into France as in the days of Napoleon. The rump Swiss government could do little but protest in response. Britain, Germany and the United States, repelled by Swiss behaviour, ultimately turned a blind eye on an international level.

The first territorial victory the Empire had, the acquiring of Geneva resonated throughout the realm as a sign that the Croix regime was successfully taking back land. But this simply wasn't enough. The lands that had been taken from the Fourth Republic remained, those being Alsace Lorraine, Nancy, and the French regions of Catalonia and Navarre. These were lands held under German and Spanish thumbs, respectively, and they were not all. The French once held Catalonia as a whole and the Rhineland, and the French speaking Wallonians of Belgium were no exception either. The Spanish Federation showed the most vocal international resistance to the acquiring of Geneva, but not as many listened.

Also on Croix's list of ambitions was the rebuilding of the French army and navy. With the authoritarian regime facing less economic burdens than most of the rest of the world during this part of history, it was not hard for them to find increased funding for their military, while other countries were forced to make budget cuts, particularly the Spanish to their south. This would soon have a major impact in the war to come. Following the Swiss cessetion, the rest of the country struggled to remain as a coherent nation.

Contemplations by Mitteleuropa throughout 1935 and early 1936 were made to divide Switzerland among ethnic lines, with most of the country going to Germany, and some token regions to Italy, with the Romansh being an autonomous province. International support for this was not particularly great, however, and so in April 1936, Mitteleuropa negotiations for an ethnic partition began to collapse.

Incapacitated by the loss of Geneva, the Swiss government started rejecting its foreign investments, returning them to their mother nations. With this, they bailed themselves out in August 1936, and so the Croix army moved into the country, once again mirroring the days of Napoleon where Switzerland had been the Helvetic Republic.

The nations of the world, who had previously been hesitant regarding the rise of Social Action, as well as the Wrangel and Turkoman regimes, were now turned against the French nation. The end of appeasment to Rocque took place in the Conference of Budapest, where the leaders of Mitteleuropa, the British Empire and Italy, came and wrote condemnation of the French occupation, calling it illegal, and ceasing all toleration for military aggression from Rocque's totalitarian state. In te meantime, he mobilised his army, airforce and navy to the best France could offer.

Tensions in Mexico against the unpopular secularised Redshirt government and the clerical members of Mexican society continued to boil within the country over this period of time. A vaguely socialist country was certainly not within the best interests of France, and so Social Action provided funding to radical opposition to the government.

Within the rightist movement, the charismatic excommunicated bishop "Father" Julien Rodriguez, declared a 'cult leader' by many across the seas, grew in popularity with his claims of miracles, his attitude to the poor and his aim to rid Mexico of all "godlessness", whether it be socialism, secularity, the Sexual Revolution or the corruption in the higher ranks of government.

Not all nationalist forces supported him, but increasing numbers saw him as being at least a valid alternative to the socialist leaning junta in Mexico City. America nominally backed the government, but many showed sympathy to the rightists, though not trusting Rodriguez.

As the situation deteriorated between the two parts of Mexican society, there was also an element among native groups who wished to preserve their heritage, with many feeling neither of the two main political camps satisfied their goals. Following an attempted coup by General Olivier Fernandez[2] in the 13th of January 1937, he was quickly ousted out of the presidential suite by forces loyal to the socialist president. This caused the central government to declare war on his rebellion, and those like it across the country, and so war began.

The Mexican Civil War was a brutal affair for certain. Divisions within both of the main factions became problematic in terms of organisation, especially for those whose only common goal was overthrowing the government. Fernandez was given support by France and Russia, and vocal support from Paraguay and Chile too. The Germans offered support for more moderate nationalist factions, with particular insistence from their Catholic subjects, though Rodriguez's rise over the course of the war infuriated them, with Germany soon withdrawing when moderate nationalist elements were thrown under the bus politically.

France was not particularly on the best terms with the southern seperatist groups such as the successful Yucatan and unsuccessful Tarascans. They funded Rodriguez only as a 'lesser of two evils" arrangement as the lines of the fragmented Mexican republic were drawn, resulting in the split. Rodriguez' new 'Holy State of Mexico', was only reluctantly funded by France, and drifted more towards internal affairs than organisation within the Pact of Steel. Even so, the training of French units during the war would teach them valuable lessons in their future campaigns in Europe.

By August of the same year, Mexico was partitioned forever, and France had its role in its downfall. While hoping to get Rodriguez's regime into his Pact to distract the United States and ther British Carribbean during the Second Great War, these plans were ultimately failures, and so the 'Holy State' would drift further and further into isolationism.

Ironically, the catalyst for war was not in Europe or Mexico, but in Asia. The fragile republic of the Phillipines had been facing Islamist insurrections in Mindanao as well as a corrupt military government which refused to open elections for democracy. The poor in that nation certainly did not seem particularly suppotive of the regime. Thus sympathy to both the extreme right and the extreme left within the country was strong. Whatever way the country was inclined though, it was unprepared for the first step in France's political career.

Knowing the fledgling nation was unstable and with two hungry neighbours to the north and west, the Phillipines was guaranteed independence by the Germans and the Spanish, their former colonial masters ironically. The ambivalent Americans also made friendly gestures, but isolationism ensured that no efforts of reintegration were taken, despite considerations. Before Bryan's presidency, a move against the Philippines was a move against the USA. But those days were over.

In the 8th of September 1937, large fleets leaving from newly French Cambodia made their way into The Proletarian Republic of Japan. Now under the leadership of Kanson Arahata, the former minister of propaganda under Sakai's time as shogun, the two countries had secret negotiations for something that would shock the world. Five days later, the Kamakawi-Doriot Non-aggression Pact was announced to the world. This move was controversial even among France's allies. Wrangel, strongly both anticommunist and anti-Japanese, almost resigned from the Pact of Steel upon hearing the news, while Turkomen was said to have given dozens of calls to Paris to express his outrage at the news.

The plans behind this pact were soon shown to the world after an alleged assault on French ships by Mindahoa resistance fighters. Complaining to the Filipino government regarding this, Rocque demanded that they pay the fine for this massacre of troops themselves. When they inevitably refused to pay on behalf of an armed rebel group, France declared war on the 18th of October. Military landings were made in Mindanao, fighting both the insurgents and the Filipino government forces. German diplomats issued an ultimatum demanding France withdraw from the unlawful occupation of Filipino land and cease the occupation of the Second Helvetic Republic. With no answer after four days, the Mitteleuropa pact declared war on France and Russia. Despite this, no German forces were sent to the Pacific to assist the Phillipines, particularly as Japanese troops invaded from the north in early November, with the plan to partition the archipelago. Regardless, it was clear to everyone. The Second Great War had begun.

(1) Vallat argued instead for a republican form of fascism without the compromise of a monarchy, as well as the establishment of a Latin block along with Italy and the Iberian countries, with no desires of replicating the old Napoleonic monarchy. His increased ambition for leadership of the country over Rocque led to the latter growing paranoid about him and taking action.

[2] As you can tell, he was born after the point of divergence and so is a new person, having a temperament quite like that of General MacArthur of otl, only in a more extreme form adapted to his context. Virulently anticommunist and a bit racist at the sides too.

With Rocque's Social Action regime in full swing, France's reascension as a global power seemed inevitable. The campaign to take back the lands that had been taken from France was one of propaganda to begin with, but it would not remain this way forever. Increased agitation by French-speaking peoples across Europe provided an indirect call to arms for the French people. Rocque argued that Germany's repeated crushing of French spirit would need to be readdressed once and for all, to make sure Germany could never again oppress the French peoples of Alsace-Lorraine, Nancy and Luxembourg. The new French Empire would take back all the lands that Napoleon had once acquired, and perhaps even more.

Unlike the Napoleon of old, Rocque did not have any desire for war with Russia, given that Wrangel's regime was similar both ideologically and in ambitions, with neither of their goals known to have overlapped with one another. While some in Croix's cabinet such as the notorious Jacques Doriot desired all of non-Russian Europe, including places as far as Poland and the Ukraine to be within the French sphere of influence, Rocque was able to guide the rest of Social Action into a conhesive order. Doriot's more radical take on fascism, more akin to the Turkomen regime than to Rocque's leadership became a problematic element, and so the Croix, the Social Action regime's secret police, ultimately took action. In September 1932, a wave of attacks and arrests were made around Paris, with hundreds arrested or outright killed. Among those arrested were Doriot himself, Xavier Vallat

, who had been proving increasingly restless in his own attempts for power (1), and over 200 others who were suspected of being 'those out to undermine the peace'. Mock trials were held and executions were taken place, with the worst traitors being given public deaths in Paris square, in an ironic homage to the French Revolution.

Emperor Louis Napoleon held little power over the French nation, but his influence was certainly profound. As a descendent of Napoleon Bonaparte himself, the founder of the First French Empire, he granted Social Action the legitimacy it needed to be secured as a significant government. The minister of propaganda Francois Coty claimed often in public speeches that Louis was bringing the nation under the unity of his ancestors, but the truth of these claims is at best dubious. Under force from Rocque's advisers, he signed approvals for whichever actions Rocque chose to implement over the nation. Following the regime's dismantling, the former emperor told us "I was hardly an emperor at all. Just a puppet, with Francois [Rocque] pulling the strings. It was honestly some of the worst days of my life." But to take a risk for the French nation, Rocque played God over him. Even his fellow monarchists found such behaviour repulsive. The action that would need to be taken for the new empire was to continue purges of disloyal elements, and increase propaganda production to rally fears of the nation upon the Germans, and soon the British as ties with them became increasingly severed as Britain went towards isolation.

The spring of 1933 proved to be an eventful and helpful year for the regime. With the situation in the eastern satellites of Germany deteriorating, France pressed its advantage with the already reduced demilitarised zone. With German forces repressing rebellion in Poland and the Ukraine (who also started to fight each other), Rocque seized his chance and marched east. The zone was fully reoccurred in a week, with only minor resistance present. For the Germans did not allow demilitarised French to participate in elections, they were at the mercy of the German military. Now though, the French military moved in right up to the German border, with Rocque and Social Action setting his eyes upon the lost provinces of Nancy, Alsace Lorraine and Luxembourg, as well as the industrially developed Saarland. With order restored here, the unification of the French people there with their motherland proved a great boost of morale. Yet there remained French speaking peoples outside the motherland too-not just in Germany and Spain, but also in such places as Belgium and Switzerland. These places too would require 'liberation' in Rocque's eyes, and the non-Francophone living there would be vassalised and granted chances to convert to French language, culture and even racial characteristics. This would certainly be carried on in France's North African colonies such as Algeria and Tunisia, as increased amounts of settlers poured into the regions. The living space for French people needed to grow, after all. At least in Rocque's eyes.

With militarisation under way, France's new economy was once again on the rise. The military was an area particulary emphasised under the regime, with the building of a new, technologically up to date air force was considered essential. The army and navy were already quite sizeable, so the only necessary changes were purging the officer corps to ensure loyalty to Social Action and its principles. As the year progresses, the Rocque dictatorship begin its preparations for the Second Great War. The French military was not ready to wage war against the nation's of Germany and Spain, who took its land, or even against the smaller Belgians and Swiss, so they needed a weaker target to start with and learn from.

The Recolonisation that occurred was the first major step in France's territorial expansion. With Cambodia disorganised and outside Japan's new sattelites states, it was left vulnerable to attack. In an era where colonialism was a significant element, Rocque's regime set apart the first step in reclaiming the lost Indochina. Mobilising a fleet in the thousands, Social Action began the reclamation of Cambodia- it's own Reconquista in the eyes of the world.

In December 1933, the first landings were made. While outnumbered by natives, the French possessed superior technology, discipline and training to the villagers and local feudal armies present. The events mirrored the first colonisation of Cambodia, only these were more intense in their form. The local communities quickly bent their knees in submission to their old overlords, only these were more aggressive and less tolerant of rebellion, not wishing to repeat the mistakes of their ancestors. Little Vietnam became annexed by its larger neighbour. The Free territory to the south-east once again geared itself as its imperialist neighbour fell, with thousands preparing to flee once more to a new land. The anarchists of Nauru as well began to prepare fleeing as the Japanese went to reclaim their islands. Within ten weeks, Cambodia had fallen once more to the new French military. Tens of thousands of anarchists fled these free territories once again. A new anarchic zone was developing within the failed state of Bolivia, and so this was the destination of the anarchist experiment. In the meantime, the French reclamation of Indochina had begun. It would be years before the second phase began, with the other nations as Japanese satellites, but it would begin again.

Around 1934, the la Croix government went into negotiations regarding a period of instability in Switzerland. With the economic declines across the world, Switzerland was hit particularly hard during the beginning of the 1930s, with many investments in that nation being withdrawn, their sources of income declined alongside the nations they supplied, and so living standards and wages started to decrease. In this new unstable era, old tensions rose again.

Following the assassination on the 3rd of November 1932 of Geneva's Président du Conseil administratif, Gustav Ador by a German-speaking nationalist of a local fringe protestant Pan-German group, there were increasing tensions between the different cultural groups within Switzerland. After this, tensions that had been dormant since the Sonderbund of the 19th century rose once more between German and French populations, as well as between Catholics and Protestants. With this happening, the country's political climate began to polarise away from the standard party models which had dominated before. With the government in Bern favouring the German majority a few too many times, Pan-French groups in Geneva and it's respective area campaigned increasingly to separate from Switzerland, also hoping to get past the government's seperation of Church and State. Rocque welcomed such ideas, and soon began incorporating and encouraging such separatist movements in the country. His creation of a "Pan-romantic" identity for the French people would help glue the French race together against the oppressive Germanics who had repeatedly put them down for centuries in Germany and in England. With a stagnating economy and racial tensions, the previously stable democracy in that nation began to deteriorate.

Germany and the United Kingdom both independently backed the Swiss government, for despite the hardships, many still had significant investments in that country, as a neutral area and place of stability within an increasingly hostile continent. While both normally at odds with one another, the fires stoked by the fascist French and Russians were driving them closer together, something that would eventually spell the downfall of this ideology and both empires. Along with the Turkish, Paraguay, Peru and Colombia, the move towards extreme nationalism was set to change the course of history.

But Swiss partisans soon put an end to this, as the Christmas Massacre took place. A group of French-speaking protesters spoke out against the German favouritism and cultural supremacy present in the neutral nation. Though peaceful, the conservative, unstable Federal Council had none of it, and due to miscommunication, opened fire on the protesters. Riots broke out, and even many international benefactors condemned the act. Seitzerland's status of neutrality was now compromised.

The French members of te council fell out from this, and the council faced major upheaval as a result of the disaster. To make matters worse, French nationalists grew in power and influence, using the massacre to justify rebellion and soon secession. In January 1935, the French parts of Switzerland finally broke off from the main republic, forming the short-lived National Republic of Greater Geneva, focussed on the French speaking majority there. Quick diplomacy by Croix and his followers brought this fledgling nation under sway, and on the 3rd of February 1935, Geneva was once more annexed into France as in the days of Napoleon. The rump Swiss government could do little but protest in response. Britain, Germany and the United States, repelled by Swiss behaviour, ultimately turned a blind eye on an international level.

The first territorial victory the Empire had, the acquiring of Geneva resonated throughout the realm as a sign that the Croix regime was successfully taking back land. But this simply wasn't enough. The lands that had been taken from the Fourth Republic remained, those being Alsace Lorraine, Nancy, and the French regions of Catalonia and Navarre. These were lands held under German and Spanish thumbs, respectively, and they were not all. The French once held Catalonia as a whole and the Rhineland, and the French speaking Wallonians of Belgium were no exception either. The Spanish Federation showed the most vocal international resistance to the acquiring of Geneva, but not as many listened.

Also on Croix's list of ambitions was the rebuilding of the French army and navy. With the authoritarian regime facing less economic burdens than most of the rest of the world during this part of history, it was not hard for them to find increased funding for their military, while other countries were forced to make budget cuts, particularly the Spanish to their south. This would soon have a major impact in the war to come. Following the Swiss cessetion, the rest of the country struggled to remain as a coherent nation.

Contemplations by Mitteleuropa throughout 1935 and early 1936 were made to divide Switzerland among ethnic lines, with most of the country going to Germany, and some token regions to Italy, with the Romansh being an autonomous province. International support for this was not particularly great, however, and so in April 1936, Mitteleuropa negotiations for an ethnic partition began to collapse.

Incapacitated by the loss of Geneva, the Swiss government started rejecting its foreign investments, returning them to their mother nations. With this, they bailed themselves out in August 1936, and so the Croix army moved into the country, once again mirroring the days of Napoleon where Switzerland had been the Helvetic Republic.

The nations of the world, who had previously been hesitant regarding the rise of Social Action, as well as the Wrangel and Turkoman regimes, were now turned against the French nation. The end of appeasment to Rocque took place in the Conference of Budapest, where the leaders of Mitteleuropa, the British Empire and Italy, came and wrote condemnation of the French occupation, calling it illegal, and ceasing all toleration for military aggression from Rocque's totalitarian state. In te meantime, he mobilised his army, airforce and navy to the best France could offer.

Tensions in Mexico against the unpopular secularised Redshirt government and the clerical members of Mexican society continued to boil within the country over this period of time. A vaguely socialist country was certainly not within the best interests of France, and so Social Action provided funding to radical opposition to the government.

Within the rightist movement, the charismatic excommunicated bishop "Father" Julien Rodriguez, declared a 'cult leader' by many across the seas, grew in popularity with his claims of miracles, his attitude to the poor and his aim to rid Mexico of all "godlessness", whether it be socialism, secularity, the Sexual Revolution or the corruption in the higher ranks of government.

Not all nationalist forces supported him, but increasing numbers saw him as being at least a valid alternative to the socialist leaning junta in Mexico City. America nominally backed the government, but many showed sympathy to the rightists, though not trusting Rodriguez.

As the situation deteriorated between the two parts of Mexican society, there was also an element among native groups who wished to preserve their heritage, with many feeling neither of the two main political camps satisfied their goals. Following an attempted coup by General Olivier Fernandez[2] in the 13th of January 1937, he was quickly ousted out of the presidential suite by forces loyal to the socialist president. This caused the central government to declare war on his rebellion, and those like it across the country, and so war began.

The Mexican Civil War was a brutal affair for certain. Divisions within both of the main factions became problematic in terms of organisation, especially for those whose only common goal was overthrowing the government. Fernandez was given support by France and Russia, and vocal support from Paraguay and Chile too. The Germans offered support for more moderate nationalist factions, with particular insistence from their Catholic subjects, though Rodriguez's rise over the course of the war infuriated them, with Germany soon withdrawing when moderate nationalist elements were thrown under the bus politically.

France was not particularly on the best terms with the southern seperatist groups such as the successful Yucatan and unsuccessful Tarascans. They funded Rodriguez only as a 'lesser of two evils" arrangement as the lines of the fragmented Mexican republic were drawn, resulting in the split. Rodriguez' new 'Holy State of Mexico', was only reluctantly funded by France, and drifted more towards internal affairs than organisation within the Pact of Steel. Even so, the training of French units during the war would teach them valuable lessons in their future campaigns in Europe.

By August of the same year, Mexico was partitioned forever, and France had its role in its downfall. While hoping to get Rodriguez's regime into his Pact to distract the United States and ther British Carribbean during the Second Great War, these plans were ultimately failures, and so the 'Holy State' would drift further and further into isolationism.

Ironically, the catalyst for war was not in Europe or Mexico, but in Asia. The fragile republic of the Phillipines had been facing Islamist insurrections in Mindanao as well as a corrupt military government which refused to open elections for democracy. The poor in that nation certainly did not seem particularly suppotive of the regime. Thus sympathy to both the extreme right and the extreme left within the country was strong. Whatever way the country was inclined though, it was unprepared for the first step in France's political career.

Knowing the fledgling nation was unstable and with two hungry neighbours to the north and west, the Phillipines was guaranteed independence by the Germans and the Spanish, their former colonial masters ironically. The ambivalent Americans also made friendly gestures, but isolationism ensured that no efforts of reintegration were taken, despite considerations. Before Bryan's presidency, a move against the Philippines was a move against the USA. But those days were over.

In the 8th of September 1937, large fleets leaving from newly French Cambodia made their way into The Proletarian Republic of Japan. Now under the leadership of Kanson Arahata, the former minister of propaganda under Sakai's time as shogun, the two countries had secret negotiations for something that would shock the world. Five days later, the Kamakawi-Doriot Non-aggression Pact was announced to the world. This move was controversial even among France's allies. Wrangel, strongly both anticommunist and anti-Japanese, almost resigned from the Pact of Steel upon hearing the news, while Turkomen was said to have given dozens of calls to Paris to express his outrage at the news.

The plans behind this pact were soon shown to the world after an alleged assault on French ships by Mindahoa resistance fighters. Complaining to the Filipino government regarding this, Rocque demanded that they pay the fine for this massacre of troops themselves. When they inevitably refused to pay on behalf of an armed rebel group, France declared war on the 18th of October. Military landings were made in Mindanao, fighting both the insurgents and the Filipino government forces. German diplomats issued an ultimatum demanding France withdraw from the unlawful occupation of Filipino land and cease the occupation of the Second Helvetic Republic. With no answer after four days, the Mitteleuropa pact declared war on France and Russia. Despite this, no German forces were sent to the Pacific to assist the Phillipines, particularly as Japanese troops invaded from the north in early November, with the plan to partition the archipelago. Regardless, it was clear to everyone. The Second Great War had begun.

(1) Vallat argued instead for a republican form of fascism without the compromise of a monarchy, as well as the establishment of a Latin block along with Italy and the Iberian countries, with no desires of replicating the old Napoleonic monarchy. His increased ambition for leadership of the country over Rocque led to the latter growing paranoid about him and taking action.

[2] As you can tell, he was born after the point of divergence and so is a new person, having a temperament quite like that of General MacArthur of otl, only in a more extreme form adapted to his context. Virulently anticommunist and a bit racist at the sides too.

Last edited:

Great update!!!

Question, do Communist Japanese soldiers ITTL still look like OTL IJA soldiers (just with Communist overtones)?

And what's the official name of Japan's army again?

Question, do Communist Japanese soldiers ITTL still look like OTL IJA soldiers (just with Communist overtones)?

And what's the official name of Japan's army again?

ThanksGreat update!!!

Question, do Communist Japanese soldiers ITTL still look like OTL IJA soldiers (just with Communist overtones)?

And what's the official name of Japan's army again?

Technologically, it is quite similar, though given it is a socialist state, there is little to none of the xenophobia (at least on a national or institutional level) that hindered their science program in our timeline. Aesthetically, there's definitely more of a 'worker friendly' vibe to their new uniform design than the old ones.

I'll have to look back in detail but I believe it's along the lines of the People's Navy/Army.

Thanks.Thanks

Technologically, it is quite similar, though given it is a socialist state, there is little to none of the xenophobia (at least on a national or institutional level) that hindered their science program in our timeline. Aesthetically, there's definitely more of a 'worker friendly' vibe to their new uniform design than the old ones.

I'll have to look back in detail but I believe it's along the lines of the People's Navy/Army.

Oh certainly. Not as bad as OTL's Nazis of course, but certainly not the kind of people you want to hop into bed with either. At least not without something significant to gain too.Social Action is villainous right?

So they're more Mussolini's "We will restore our glory!" than Hitler's "Kill 'em all and live in their houses!"?

Basically, yes.So they're more Mussolini's "We will restore our glory!" than Hitler's "Kill 'em all and live in their houses!"?

Japan (1932-1937)

Jonathan London, The Twentieth Century and It's Course, 2012, pp.67-70

Sakai's death in 1929 had led to the brief period of council rule, but even the most optimistic politians in the Proletarian Republic knew this was only a temporary arrangement. A new People's Shogun needed to be elected to provide a figurehead for the people and the nation.

Kazua attempted a coup in July 1932 to take over the nation, wishing to create a more authoritarian Japanese economy[1] with total control over all aspects of life, designed to be optimised for the benefit of the people. He gained support from Yamakawa, who wished a greater focus on the rural peasant's rights, forming a rival coup-attempt to Kazua. Despite support from some of the military, Both coups proved ultimately a failure and within a week, Kazua was executed and Yamakawa was imprisoned without trial and exiled. Though he died in 1935 from unknown diseases in Indonesia, some of both of their ideas would live on and have significant implications in the development of twentieth century communism, particularly the rise of the Pembebasan Revolusioner Rakyat developing from Marxist-Kotoism[2]. Meanwhile in Japan; the council's elections resumed in October that year.

The process was long and intense, but ultimately led to fruition the following year in June 1933. Following the discrediting of opposition through the efficient position of being the former minister of propaganda, Kanson Arahata managed to manoeuvre himself into the position to being considered the best hope for the Republic, and was soon ushered in as 'People's Shogun'. With the rise of his regime, he prided himself as being Sakai's successor, establishing his position as founder of the republic with statues and even holidays named in his honour[3]. Despite his position, he played an image of false humility to prevent other members of the People's Council from deeming him a threat and removing him from power. The main changes he made from Sakai's leadership was an increase in the size of the army and navy, which he argued would help protect the republic and its allies in Indochina from 'Imperialist aggression'. It was certainly true that Sakai's spending on military concerns was underwhelming in the eyes of many in the party, especially given the risk of the hard-line anticommunist Chiang Shek coming to power in China. Even when this didn't happen, many understood Arahata's emphasis on militarisation. The wish to spread socialism globally was pressured by the council, though Arahata did put emphasis on suppressing this movement within the party, wishing to quitely secure his own grip on power rather than export the Revolution, at least not directly.

The Rice Boom of 1934 was one of the big success' of Arahata's early rulership as People's Shogun. The decent harvest was a result of an unusually long summer and decent rains beforehand, as well as foreign policy gaining beneficiaries among non-communist nations wishing to gain rice exports, including China and the United States. Arahata was thus praised for this development of the food situation, something that was to be essential as the continuations of the revitalisation plans from Sakai continued. Japan already had industry and a modernised military before the revolution, unlike neighbouring nations such as Russia and China, but nevertheless the need to keep militarily and economically up to date was considered paramount. With a modernised nation itself, Japan now started to serve as a benefactor towards the Indochinese regimes it had befriended. Many in his council considered his aid sent over insufficient, given the contemporary French reclamation of Cambodia, demanding that Japan directly administrate these regions to ensure the locals were trained, defensible and with a solid source of industry to use, even suggesting to cut down yet vast forests of the region. However, Arahata spun this off as a remnant of colonialism; directly intervening would make Japan no different to the imperialist nations around it. Without this source, the council backed down for now. However, behind Arahata's nose, signs of discontent were building. This would only further be amplified by other decisions the 'People's Shogun' made.

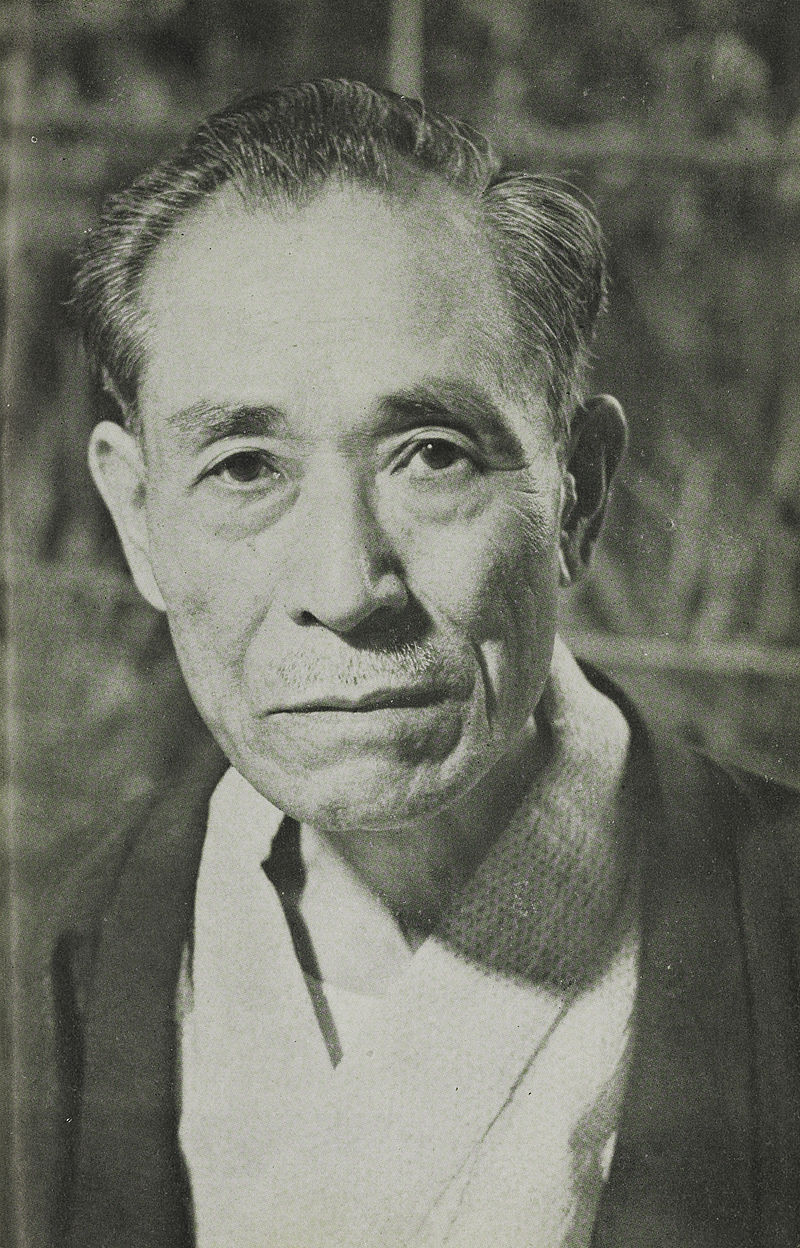

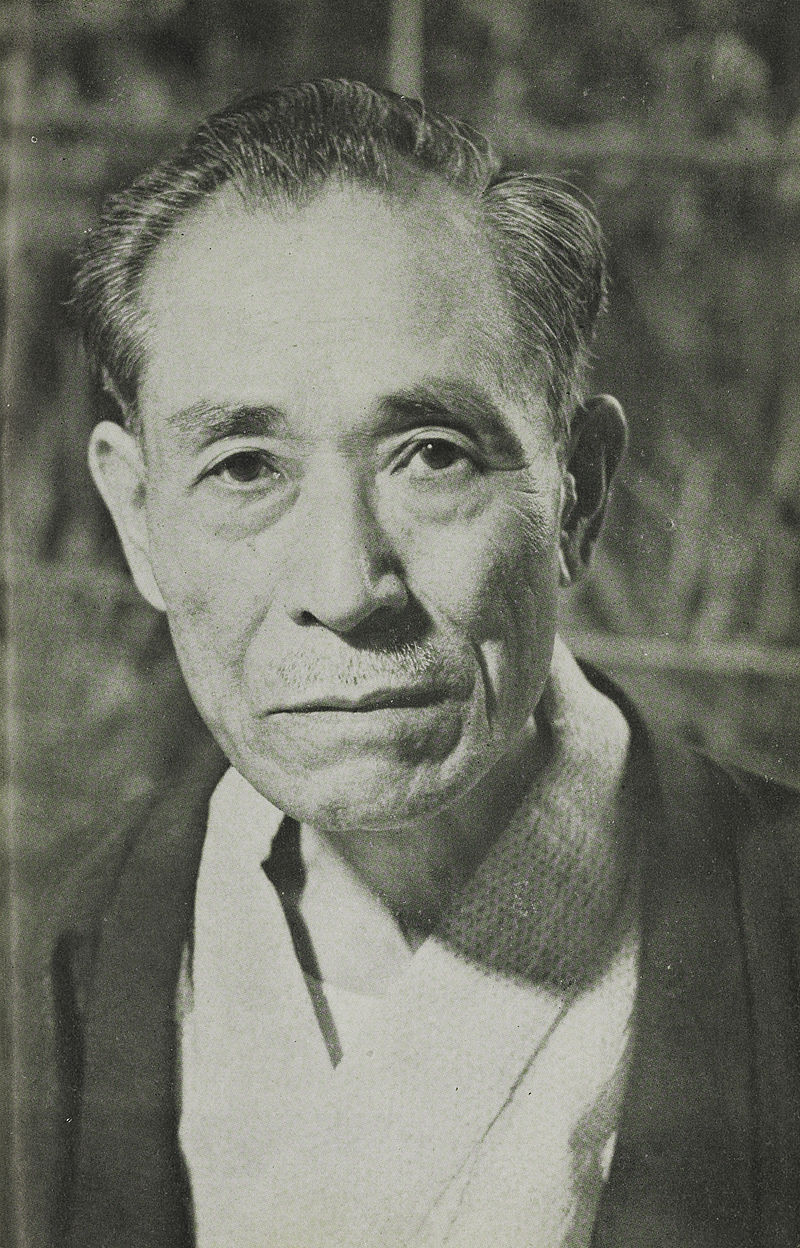

The former People's Shogun, well over a decade after he was deposed, and only a few short months before his mysterious death, believed by many to have been an assassination.

The year of 1935 was a somewhat tense year diplomatically for the Proletarian Republic, as increased Russian activity in China led to armament building up, finally spilling into war in October as the Russians launched a full scale assault from Qinghai in the west and Manchuria in the north. Tokyo, despite differences between the the two regimes, funded its mainland neighbour, led by the friendly Jingwei, who had ousted Shichang in the previous year's election, against the imperialists. The success of the French acquiring of Geneva shocked almost all in the Japanese council, and so desires to mobilise and prevent the French from strengthening their toehold in Asia were built up. The funding of arms, tactics and even volunteer divisions in exchange for food and natural resources was greatly profitable for Japan, which lacked a great deal of its own natural resources. The support of the left wing parties within China's suspended democracy spread hopes that a socialist revolution would arise there in the long term, at least temporarily. The need to contain Russian expansion was also considered of paramount importance to the Japanese at this point, as Wrangel's regime was openly anti-communist, and clearly wished to further eliminate the Japanese communists. Arahata made condemnations of the French takeover of Switzerland alongside the other nations of the world, and in September of that year, began conscription within his country, making it compulsory for all men and women between the ages of 18 and 40 to have at least 3 years of military service under their belt. This would play a significant role in the wars to come.

As the next two years rolled along, the country experienced relative prosperity, growing rich off trade and arming with China, Germany and the United States. The former anarchist fortress in Nauru was retaken and communist rule restored. The former emperor died and his son was proclaimed regent, though he would never sit the throne of Japan. Politically, the situation was quite stable, and the development of local authorities started despite the move towards a wartime economy. However, the hostility with Russia put its people on edge, and this prosperity was certainly a fragile one. Japan seemed ready for war from an economic perspective, but the people living in Japan certainly did not feel that way. Nevertheless, the People's Shogun felt his buildup would be wasted if his newly developed military was not put to use, especially to use resources that he felt were needed. With no opportunities coming to conduct war with the French in Indochina, or against Thailand after attempts to fund local socialist groups fell flat, his jingoism felt less and less satisfied. Within 1937, a building up of military presence in the southernmost islands led to complaints and militarisation from the Manilla government in the Philippines, who saw this as encroaching on their territory. Arahata saw the great resources of the Philippines as being of great potential use, both directly to Japan and to fund the economy in a war against Russia, which he regarded as inevitable. He also had support from some of the council, particularly foreign minister Kamakawi, who saw this as a way to expand the Revolution and establish another Proletarian Republic in the world. Many wanted a casus-belli against the Filippinos to be carried out as soon as possible, regardless of international condemnation. Many more in the counsel opposed such a move as imperialistic, instead seeing ripe territory within the colonies of Europe, and in the oppressed Koreans, Mongolians and Manchu under Russian rule. Arahata's more pragmatic ideals however, made him see friendship in the most unlikely of places.

The Non-Aggression Pact between Fascist France and Communist Japan on the 13th of October 1937 shocked many, both internationally and within the cabinet. Foreign Minister Marcel Déat had promised Japan the oppurtunity to spread the Revolution throughout East Asia, even offering to divide China with the Russians, and attack British and Dutch colonies nearby. This was clearly a ruse by Social Action to distract Japan with a major war, which fortunately Arahata refused to listen to. Nevertheless, it led to enormous criticism against his policies and personality[4].

It was in fact considered such an outrage among the counsel that many began to plot to have Arahata removed, for betraying Sakai's memory and Marx's ideals. The conspirators gathered round the figurehead of Fukomoto, who also wished to remove the privileges of the former royal family on Okinawa, as a final remnant of the pre-war regime. Another conspirator with his own agenda was Sen Katayama, the formerly disgraced second in command of Sakai, who had found himself pardoned in late 1934 by Arahata's judges. Katayama repayed him with treachery, being involved in the conspiracy to remove him from power and prevent a great war that would cause the collapse of the regime he had worked so hard to create. However, it would take months for the plans to start to mobilise, and more than one attempt was made to remove Arahata.

The first came just before the invasion of the northern Philippines began, on the 3rd of November 1937, under the pretense of a drunken brawl between different members of the military. This soon escalated into a shoot-out, with the conspirators charging parliament and attempting Arahata's life. Three members of the People's Council and more than twenty civilians were killed in this attack, and dozens were injured. However, the secret police, mostly answering directly to Arahata soon dealt with the conspirators and had them all hanged, though they didn't manage to find out who had started the fights in the first place. This 'Night of the Broken Glass', named for the first bottle of whiskey that had been thrown during the initial brawl, would go down in history as the start of the Troubles, a difficult time for the leadership of the Proletarian Republic. No more attempts were made on Atahama's leadership that year, even while subduing the Filipinos, but more would come the following year.

The State of the Filipino War of Resistance on the 1st of January 1938.

[1] somewhat more like OTL's Leninism or Gramsciism, whereas Sakai's model of communism is a bit like a rough cross between Menshevism and Luxembourgism.

[2] With an agrarian focus and aims to liberate the peasants and such, this branch of communism is like a somewhat tamer version of Maoism with Syndicalist, Narodnik and even Islamic influence.

[3] Sound familiar? Granted this is more sincere than a certain OTL socialist leader's pandering.

[4] Even his own allies such as his foreign minister Kamakawi privately showed protest to this diplomatic move, warning that the fascist regime, with a powerful navy and desire to restore control in the Pacific, would not tolerate a communist Japan for long, if at all. Perhaps if Arahata hadn't ignored these warnings, Japan may not have suffered the early blunders it had during Operation Leapfrog.

Sakai's death in 1929 had led to the brief period of council rule, but even the most optimistic politians in the Proletarian Republic knew this was only a temporary arrangement. A new People's Shogun needed to be elected to provide a figurehead for the people and the nation.

Kazua attempted a coup in July 1932 to take over the nation, wishing to create a more authoritarian Japanese economy[1] with total control over all aspects of life, designed to be optimised for the benefit of the people. He gained support from Yamakawa, who wished a greater focus on the rural peasant's rights, forming a rival coup-attempt to Kazua. Despite support from some of the military, Both coups proved ultimately a failure and within a week, Kazua was executed and Yamakawa was imprisoned without trial and exiled. Though he died in 1935 from unknown diseases in Indonesia, some of both of their ideas would live on and have significant implications in the development of twentieth century communism, particularly the rise of the Pembebasan Revolusioner Rakyat developing from Marxist-Kotoism[2]. Meanwhile in Japan; the council's elections resumed in October that year.

The process was long and intense, but ultimately led to fruition the following year in June 1933. Following the discrediting of opposition through the efficient position of being the former minister of propaganda, Kanson Arahata managed to manoeuvre himself into the position to being considered the best hope for the Republic, and was soon ushered in as 'People's Shogun'. With the rise of his regime, he prided himself as being Sakai's successor, establishing his position as founder of the republic with statues and even holidays named in his honour[3]. Despite his position, he played an image of false humility to prevent other members of the People's Council from deeming him a threat and removing him from power. The main changes he made from Sakai's leadership was an increase in the size of the army and navy, which he argued would help protect the republic and its allies in Indochina from 'Imperialist aggression'. It was certainly true that Sakai's spending on military concerns was underwhelming in the eyes of many in the party, especially given the risk of the hard-line anticommunist Chiang Shek coming to power in China. Even when this didn't happen, many understood Arahata's emphasis on militarisation. The wish to spread socialism globally was pressured by the council, though Arahata did put emphasis on suppressing this movement within the party, wishing to quitely secure his own grip on power rather than export the Revolution, at least not directly.

The Rice Boom of 1934 was one of the big success' of Arahata's early rulership as People's Shogun. The decent harvest was a result of an unusually long summer and decent rains beforehand, as well as foreign policy gaining beneficiaries among non-communist nations wishing to gain rice exports, including China and the United States. Arahata was thus praised for this development of the food situation, something that was to be essential as the continuations of the revitalisation plans from Sakai continued. Japan already had industry and a modernised military before the revolution, unlike neighbouring nations such as Russia and China, but nevertheless the need to keep militarily and economically up to date was considered paramount. With a modernised nation itself, Japan now started to serve as a benefactor towards the Indochinese regimes it had befriended. Many in his council considered his aid sent over insufficient, given the contemporary French reclamation of Cambodia, demanding that Japan directly administrate these regions to ensure the locals were trained, defensible and with a solid source of industry to use, even suggesting to cut down yet vast forests of the region. However, Arahata spun this off as a remnant of colonialism; directly intervening would make Japan no different to the imperialist nations around it. Without this source, the council backed down for now. However, behind Arahata's nose, signs of discontent were building. This would only further be amplified by other decisions the 'People's Shogun' made.

The former People's Shogun, well over a decade after he was deposed, and only a few short months before his mysterious death, believed by many to have been an assassination.