You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Out of the Ashes: The Byzantine Empire From Basil II To The Present

- Thread starter Vasilas

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

I think a lot of people will benefit from my answer to this question, since I had not been able to write for quite a long time and people have most likely forgotten details.

Mostly luck (in avoiding bad luck) at a couple of critical junctures.

They are still mostly the same people, but they avoided the major slumps in that period and are pushing non-stop, sorta like the Republic in the first and second centuries. Phokas actually did not get much done himself. The POD was that he felt Constantinople needed his attention more than Anatolia, and so he sent John east, who was younger and (from what I can see from his brief reign) quite a bit more aggressive. Not major changes overall from OTL in territorial terms (Aside from Sicily, the rest of the red in the map is OTL although might be a couple of years ahead of OTL), but it was enough to unnerve Phokas who sent John to Sicily, where he met George Maniakes levels of success reasonable in my mind). Phokas on the other hand really fucked up the situation in the Balkans (due to having a substantial number of troops in Sicily) compared to OTL, leading to crushing defeats and finally resignation-paving the way for John to seize the power. I also had the Phokas family potential rebels (Leo and Bardas) die in the Bulgarian campaign to make things smoother for John, who becomes Basileus and wins against the Rus ans Bulgarians at Arcadiopolis (exactly as OTL, even dates-the Balkans blue not much different from OTL).

Meanwhile the Fatimids had a slightly harder time getting Egypt (I think I made them 2-4 years behind schedule)-not unrealistic, since they failed a couple of times in OTL too and just waited to get their house in order for a final push. This means the Levantine states lack a strong protector, and that, coupled with Roman naval dominance meant that Tzimiskes faced fewer issues in his second set of eastern campaigns. Nonetheless, I again kept the gains mostly similar to OTL (these were lost in the chaos of the first twenty years of Basil's reign in our timeline). Then he does not die when Basil Lekepenos wants him to (big POD).

A couple of minor PODs along the way had been Tzimiskes earlier (960s campaign) had poisoned ground relations between muslims and christians via wholesale expulsion, massacre and forced conversion of the former (y' know, standard ethnic cleansing, nothing to see here), while using kid gloves for the latter; and him actually having a biological kid in Syria. Said kid ends up married for Basil for dynastic stability, and Basil-having nothing to do since John is alive and well, decides to go check out Anatolia. He quickly realizes that he doesnt have too much power, and works to correct that. Baghdad was his major lucky break (the Abassid Caliph did in fact ask for his help against the Shia Emir, only to well, get burned), making him a bit irreplaceable. The already deteriorating Christian/Muslim relationship in the Levant gets worse after this (killing a Patriarch-same as OTL btw- does not help much), and the powder keg blows up soon, with the Empire and Fatimids fighting it out. Both are aided by (muslim) Bedouin tribes, who have not dealt with the issues their urban cousins had been facing for the past twenty years and will go the side who pays best. The Romans are that side, unfortunately. Continous fighting with a Roman coast and a Fatimid interior, until the Romans get complete naval dominance with Venetian assistance (attack on merchants in Egypt) and are able to invade the Delta. The Caliph loses his nerve and retreated (bad move, the Romans had limited ability to deal with him in the interior, but he did get scared about his supply train vanishing), leading to a crushing Roman ally victory in the Levant.

The West was described in the last update. The cometopouli fighting is similar to OTL, and John simply makes Samuel a better offer than a distracted court OTL could. Arab-Roman de-facto alliance in Southern Italy is also not new news, but it just played out in a way to make it work out better.

So the major differences from OTL is that:

1. Higher interfaith tension in Levant, making it easy for Byzantines who claim to champion the majority community. No one actually believes that, but they seem like they will be distant masters than the ones killing your family right now. Some radicalization, and the Syrian Church nearly collapsing (easy target for both muslim mobs and Imperial agents) helps.

2. John actually living, and giving the Empire two hyper-competent Emperors at a time in OTL when they had one young boy fighting to survive. 976-990s was essentially a huge slump for the Empire, allowing Bulgarians and Fatimids to gain while Basil got his house in order. Here, most usurper wannabes wind up dead and you are left with John and Basil. Could be a recipe for bad civil war, but they choose to fight on different fronts (both know the age difference allows only one outcome). Basil was in OTL described to be someone who worked more for the Empire than for himself, and while that is certainly more hagiography than fact, some aspects of it are believable enough for me to think that he would not force the issue just for marginally more power.

3. Thus they have two good leaders on two fronts, who are actually linked by marriage.

Does this explain most of it?

It's been a while since I've read this TL and I've forgotten quite a bit of the details. Could you remind me why Nikephoros, John and Basil have done so much better than OTL (Which they were already pretty successful)?

Mostly luck (in avoiding bad luck) at a couple of critical junctures.

They are still mostly the same people, but they avoided the major slumps in that period and are pushing non-stop, sorta like the Republic in the first and second centuries. Phokas actually did not get much done himself. The POD was that he felt Constantinople needed his attention more than Anatolia, and so he sent John east, who was younger and (from what I can see from his brief reign) quite a bit more aggressive. Not major changes overall from OTL in territorial terms (Aside from Sicily, the rest of the red in the map is OTL although might be a couple of years ahead of OTL), but it was enough to unnerve Phokas who sent John to Sicily, where he met George Maniakes levels of success reasonable in my mind). Phokas on the other hand really fucked up the situation in the Balkans (due to having a substantial number of troops in Sicily) compared to OTL, leading to crushing defeats and finally resignation-paving the way for John to seize the power. I also had the Phokas family potential rebels (Leo and Bardas) die in the Bulgarian campaign to make things smoother for John, who becomes Basileus and wins against the Rus ans Bulgarians at Arcadiopolis (exactly as OTL, even dates-the Balkans blue not much different from OTL).

Meanwhile the Fatimids had a slightly harder time getting Egypt (I think I made them 2-4 years behind schedule)-not unrealistic, since they failed a couple of times in OTL too and just waited to get their house in order for a final push. This means the Levantine states lack a strong protector, and that, coupled with Roman naval dominance meant that Tzimiskes faced fewer issues in his second set of eastern campaigns. Nonetheless, I again kept the gains mostly similar to OTL (these were lost in the chaos of the first twenty years of Basil's reign in our timeline). Then he does not die when Basil Lekepenos wants him to (big POD).

A couple of minor PODs along the way had been Tzimiskes earlier (960s campaign) had poisoned ground relations between muslims and christians via wholesale expulsion, massacre and forced conversion of the former (y' know, standard ethnic cleansing, nothing to see here), while using kid gloves for the latter; and him actually having a biological kid in Syria. Said kid ends up married for Basil for dynastic stability, and Basil-having nothing to do since John is alive and well, decides to go check out Anatolia. He quickly realizes that he doesnt have too much power, and works to correct that. Baghdad was his major lucky break (the Abassid Caliph did in fact ask for his help against the Shia Emir, only to well, get burned), making him a bit irreplaceable. The already deteriorating Christian/Muslim relationship in the Levant gets worse after this (killing a Patriarch-same as OTL btw- does not help much), and the powder keg blows up soon, with the Empire and Fatimids fighting it out. Both are aided by (muslim) Bedouin tribes, who have not dealt with the issues their urban cousins had been facing for the past twenty years and will go the side who pays best. The Romans are that side, unfortunately. Continous fighting with a Roman coast and a Fatimid interior, until the Romans get complete naval dominance with Venetian assistance (attack on merchants in Egypt) and are able to invade the Delta. The Caliph loses his nerve and retreated (bad move, the Romans had limited ability to deal with him in the interior, but he did get scared about his supply train vanishing), leading to a crushing Roman ally victory in the Levant.

The West was described in the last update. The cometopouli fighting is similar to OTL, and John simply makes Samuel a better offer than a distracted court OTL could. Arab-Roman de-facto alliance in Southern Italy is also not new news, but it just played out in a way to make it work out better.

So the major differences from OTL is that:

1. Higher interfaith tension in Levant, making it easy for Byzantines who claim to champion the majority community. No one actually believes that, but they seem like they will be distant masters than the ones killing your family right now. Some radicalization, and the Syrian Church nearly collapsing (easy target for both muslim mobs and Imperial agents) helps.

2. John actually living, and giving the Empire two hyper-competent Emperors at a time in OTL when they had one young boy fighting to survive. 976-990s was essentially a huge slump for the Empire, allowing Bulgarians and Fatimids to gain while Basil got his house in order. Here, most usurper wannabes wind up dead and you are left with John and Basil. Could be a recipe for bad civil war, but they choose to fight on different fronts (both know the age difference allows only one outcome). Basil was in OTL described to be someone who worked more for the Empire than for himself, and while that is certainly more hagiography than fact, some aspects of it are believable enough for me to think that he would not force the issue just for marginally more power.

3. Thus they have two good leaders on two fronts, who are actually linked by marriage.

Does this explain most of it?

Last edited:

Thanks for the summary. How's the situation in Bulgaria now? It seems like the conquest was significantly less brutal than OTL so would they be more complacent subjects now?

Bulgaria is not too bad to be honest. The Rus are gone and the land is in peace. They were never particularly rebellious (when taxation did not hit predatory levels) post Basil OTL, and I don't think that has changed. They are generally complacent-but as fellow Nicene-Chalcedonian Christians in the Greek East, they are rather close to the top of the pecking order as it is. Massive changes to tax patterns could however lead to rebellion down the line (Samuel has mostly used up all the local goodwill and wont be able to pacify based on name alone). That being said, there are demographic changes---quite a few being forced out into the Levant, many going voluntarily and then a migration to Sicily down the line. The Church is also not going to compete very well with the Greek Church, and the future of the culture is not particularly positive.

How's the economy of the Empire doing? Almost constant warfare must be a serious drain on the coffers.

Not too badly. Basil saved quite a bit of money despite fighting all his career OTL, and I think the Roman economy can take the stress of the war (notice lack of any architectural projects) as Anatolia had been spared war damage. Not swimmingly well: there are internal debts, forced requisitions from Muslims/Levantines, a few loans from Venice etc (and maybe a few treaties in exchange for more money), but they are not in dire straits. The focus on the richer east/Sicily compared to Balkans means more loot as well, which helps the deal. There is of course a major expense in paying troops and bribing Bedouins to fight for them, but the Imperial economy is in far better shape than the Fatimids, who saw the war come to their home and have no functional navy left). The balance of payments is negative, but not sufficiently negative enough for default/catastrophic failure. They could have afforded at least five more years if needed be, which was beyond the means of the Fatimids.

However, they are doing badly on one major front-manpower. They have burned out far too many tagmatic soldiers in this set of wars, and by the end were desperately reliant on hires from Armenia/Caucasus, along with new levies from Bulgaria/Levant. This is why they seized the offer of peace, so that they can rebuild their armies again in a manner to better reflect the new geopolitical situation.

This could possibly be one of the greatest timelin s of the website.

Thank you.

However, they are doing badly on one major front-manpower. They have burned out far too many tagmatic soldiers in this set of wars, and by the end were desperately reliant on hires from Armenia/Caucasus, along with new levies from Bulgaria/Levant. This is why they seized the offer of peace, so that they can rebuild their armies again in a manner to better reflect the new geopolitical situation.

While we're on the topic of reorganising army, how does the Empire compare to their neighbours in terms of technology and organisation? If I recall correctly they should still be well ahead of the competition at this stage OTL.

While we're on the topic of reorganising army, how does the Empire compare to their neighbours in terms of technology and organisation? If I recall correctly they should still be well ahead of the competition at this stage OTL.

Tech wise, I don't think they are better off than the Arabs (save of course the Greek fire trump card). Somewhat more advanced than the Latin world, but not enough for that alone to win wars. Organization is significantly better than anything west of Cathay (though the Fatimids have learned their lesson well). Neither is too different from OTL at the moment.

986-1006: Golden Interlude

Chapter 5: The Golden Interlude

The year 987 found the Empire as the undisputed master of the Eastern Mediterranean, having essentially reversed most of the major territorial losses since the advent of Islam. Syria, Palestine, Sicily and even the Cities of Carthage and Alexandria had returned to the Imperial fold, while their Bulgarian and Arab Lords rotted in their graves or begged in exile. Even the almighty Fatimid Caliphate had been defanged with its navy reduced to ashes floating the Kaisaria harbor, and its lands filled with refugees from the Levant expelled by the Romans. There did not exist a power West of Cathay that could have matched the glory and might of the Empire of Romans-a stunning reversal from seemingly irreversible decay since the time of Justinian.

The Emperor however was left with the task of securing the peace after his glories in the field of battle. The core of professional tagma troops had been almost completely burned out by the near constant wars, but the Empire had both the means and the time to remedy that. The economic situation of the Empire was in fact much better than what the seemingly fifty year long war would indicate. West Anatolia-the most economically productive region of the Empire-had been in peace for centuries and could alone supply the requisite manpower alongside a considerable amount of tax revenue without major stress. The loot from conquered territories in fact had heavily boosted the Anatolian economy, as the wealth of Baghdad and Damascus flowed into Trebizond and Ancyra alongside returning soldiers. Thrace and Macedonia, while at peace for a much smaller duration of time, were also generating a considerable net surplus in terms of the Imperial budget, allowing Constantinople a somewhat freer hand in organizing the newly acquired territories.

The economic health of those territories on the other hand was more questionable. Southern Italy was a net drain as ever-a perpetual vanity conquest that would take years to be profitable but was seen as essential to protect the Balkan territories from any avaricious Latin power. Syria and Palestine had been looted by the armies so thoroughly that the major cities could barely support themselves, but the land was sufficiently rich that the newly empowered Christian communities leaving the secure zones could soon survive without requiring assistance from the Constantinopole. The trade caravans running through the region were theoretically also a valuable source of income, though records indicate that there was a severe contraction in the amount of goods flowing from the east via land. The traditional interpretation had long blamed political instability in Mesopotamia for this, but it now slowly being recognized that Levantine Bedouin raids were also to blame. The Empire did not attempt to extend direct control to most of the Levant, being content with the coasts and the a few major cities like Jerusalem and Damascus in the interior. Most of the land was filled with (very muslim) Arab nomadic tribes, who the Empire had used as auxiliaries in the last war and who they subsidized in the interest of maintaining peace. Constantinople extended only loose control over them, merely directing their attention to rebellious communities (oftentimes muslim, but attested to be christian a few times as well) to ensure that its interests were not compromised. This left the tribes to prey on the routes, and often demand substantial protection money, leading to an overall contraction that Constantinople mostly ignored (having never budgeted for it in the first place). The Empire however was quick to use its naval leverage in Mediterannean to encourage the Red sea trade to go via Berenike in Palestine (1) instead of Egypt, and forced a large chunk of Egyptian exports to leave via Alexandria (by only ‘insuring’ those ships). A select number of Genoese and Venetian merchants proved to be the only exceptions who were allowed purchase licenses for trading from other Egyptian ports, but the worsening situation for Nicene-Chalcedonians in Egypt made most of the Italians choose to operate out of the safety of Alexandria, with a large chunk of the insurance licenses lying unclaimed.

Money thus was not a major issue for the Empire, and the stewardship of the Finance minister Stephen of Baghdad (2) under the watchful eye of the Emperor resulted in significant surpluses. The Emperor however was not particularly happy about the seemingly worsening wealth inequality happening in the Empire, with the dynatoi driving the poor farmers of Central and East Anatolia to make sheep farms. The Makedonian dynasty had long combatted the dynatoi, but the reigns of Phokas and Tzimiskes had relieved the stress somewhat, while Basil had required their assistance in the eastern push. Like his forefathers however, he was discomfited by the influence the dynatoi had on Anatolian troops and sought to curb it. To this end, he moved to double to size of the professional tagma core, staffing it with many of the now landless young men who owed their livelihood to the Basileus and not the local magnate. The Orphans were also constituted in early 990 as an elite set of soldiers raised from the children (mostly Sicilians and Syrians) orphaned during the war. Basil’s army had collected large numbers of these children during the war, and sought to hone them to a perfect weapon of unquestionable loyalty. The historian Paul of Kallinikos was one such child ‘adopted’ by the Empire, after he and his brother were orphaned by the Kallinikos riots. A limp had doomed him to the clergy over military service (which led to considerable bitterness in his writing) but he was eager to describe the adventures of his brother Petros and other fellow Orphans, giving an unparalleled account of the era [1]. Overall however, recruitment into the armed forces was not an efficient measure for poverty alleviation, driving the Emperor to seek out alternate approaches.

This is admittedly something few men in his position power would normally prioritize, and is indeed a very strong reason behind why future historians peddled hagiography over facts when it came to Basileos Megas. The years in the camp and first hand accounts of the struggles of the poor however had moved the Emperor to take dramatic measures to reduce the number of poor in the Empire. The classical route had been via massive construction projects, but this was found to be an inefficient short time fix, and no major projects were undertaken aside from some repairs and restoration of earthquake damage. In his opinion, the only viable long term solution was to provide the poor with land for settling in, but such land was not available in great supply in the densely settled Eastern Mediterranean. Syria had lost a tremendous amount of population, but there was a large enough local population to capitalize on the newly freed up territories at a time of upheaval. Attempts to impose land ceiling measures did not extend far beyond the coastal strips where the Empire had a vicelike grip, and the Emperor refrained from enforcement via military, which would likely cost local goodwill. The alternative thus was to make land appear by impounding from groups that did not have much political support. The muslims of Syria and Sicily were a convenient scapegoat, and the farmers clinging to the faith saw their tax treble between 987 and 990, enforced by an increasingly brutal Imperial army that often sold entire villages to slavery when tax targets were not met. Such predatory taxation led to uprisings that were quickly crushed, oftentimes by Lombard/Arab auxillaries that the Empire had paid off. Many locals quickly got the drift, and abandoned their land in favor of banditry (again ruthlessly crushed by the Empire) or fleeing to Egypt as cheap labor on trade ships. Settlers from the urban poor population of Constantinople and the Aegean were quickly sent to occupy the emptied land, alongside a Greek priest to ensure that they did not ‘go local’. Some major population transfers also occurred at this time (mainly Lombards in Salerno and Benevento being sent to the Levant to be replaced by Greek settlers), but overall Imperial policy was to replace undesirables with desirables by all means necessary. Introduction of rice into imperial lands also offered a route, as the Church was compelled to use its land in Thrace to cultivate the new crop through the labor of the jobless urban poor, while the resulting high-calorie cereal flowed to the various welfare kitchens run by the Church.

These projects had visible impact, as noted by Archbishop Manfred of Cologne while reflecting on his visit to Constantinople in 995. Although his claims of there being no beggars in the street as they were all tilling church lands was clearly hyperbole designed to convince secular rulers to grant more land to his church, his utopic account of the Queen of the Cities is generally assumed to hold some truth. Venetians and Genoese nobles for instance often wrote about their discomfort with the resources Constantinople spent for its poorest, as well as the trouble they had with poor young crewmen simply defecting to the Empire. Nonetheless, even they complimented the enormous effort of the Constantinopolitan church in training a large number of priests to spread the (Nicene-Chalcedonian) word of christ. Perhaps somewhat inadvertently however, the newly educated droves of churchmen drove up the literacy of the Empire in their dual capacity as village schoolmasters, leading to a generation that would play a crucial role in the future hellenization of the Empire. The influence the Basilian reforms had over literacy is often questioned by historians in light of the fact that the Empire had always been the most literate society west of Cathay, but contemporaries often noted that the those years were special. Michael Psellus, writing a half a century afterwards, stated that there “will never again be another generation as learned as those educated by Emperor Basil” [2].

The Empire also exerted significant influence in the cultural sphere in this era. The Balkan slavs never really had a hope of keeping an identity independent of the Empire in the face of geography and the sheer wealth of Constantinople, that allowed it to dump large numbers of bilingual priests into the former Bulgarian Empire to accelerate assimilation. The nobles themselves were the first to disappear into Imperial society, with distant villagers being the last to cling on-but the inevitable cultural forces would take their toll in the years to come. Further north, the Prince of the Rus would finally convert to Christianity in 989 in exchange of being allowed to marry the Emperor’s sister Anna. This secured the Empire’s northern borders, and permitted Basil to focus on other frontiers. Large scale vassalization-often via force- of Armenian and Caucasus principalities happened from 994-1006, wherein many rulers were even coerced to will their territories to Constantinople in the absence of a direct heir. The west was a trickier matter, but there was no direct intervention in the German civil war that continued to rage. Some defensive action occurred in Italy without any change in borders, while Sardinia and Corsica were brought back to the Imperial fold. The latter indirectly catapulted the Empire into affairs in Gaul, where the Count of Provence begged assistance from a distant overlord to avoid the grip of the Kings of France (themselves emboldened by eastern front being secured by the German civil war). Nikepheros Ouranos led the tagma in the first serious military mission of this era, although they never really saw action as their presence was sufficient to have scared off the northerners. While the project led to no direct gains for the Empire, it did help extend their influence into the western Mediterranean, and secured Corsica from the north.

The south was however where the main issues of the day originated from. Caliph Al-Aziz had led his country to disaster in the wars against the Empire, but it seemed like he would be able to win the peace by ensuring that Egypt remained steadfastly loyal to him. He was fully aware that legitimate grievances of Levantine Christians had given the Empire an opening, and an equivalent Coptic uprising could be ruinous. Dividing the Melkites [3] and Copts therefore was high on his agenda, which he sought to achieve by elevating a sympathetic Coptic Patriarch into office at Cairo (his predecessor being unceremoniously chucked out by the Empire from Alexandria) and promoting Miaphysite court officials. His Melkite wife and her family were also forced to make a public conversion to Coptic Christianity (her brothers would later become Patriarchs of their new church), highlighting the extent to which he was willing to go to appease the Copts. Simultaneously Melkites were persecuted, and Italian traders soon found that their security in ports outside Alexandria was not particularly guaranteed by the Caliph. Al-Aziz’s Shia faith also led him to take moves to appease the mostly Sunni populace, especially in light of the large number of Sunni Levantine refugees fleeing Imperial persecution. The easiest route to do this was same as what Basil had achieved-via giving land to the poor. The Delta had Melkite villages ripe for persecution, and many were soon made empty by the Caliphal army to secure resources for their coreligionists. A deluge of the homeless made it to Alexandria, but the Empire did not lift a finger to defend them. Soup kitchens were all that Constantinople was willing to fund at such times, and so the Melkite masses huddled in the City of Alexander, waiting for their time. They were being joined by Copts as well, as the army was less than diligent in persecuting only the right types of christian (while the coptic church hierarchy covered those issues up). A young priest from Pelusium proved to be exactly the type of preacher the homeless and the poor desired, with his radical talk of seizing Egypt for christians once the Empire had recovered and could go to war again. Protests from the Melkite Patriarch notwithstanding, Constantinople allowed Father Thomas to continue with his sermons as they themselves felt that a fight with Egypt was inevitable in the decades to come, and a local radical population could serve them as well as it had in Syria. Al Aziz was also aware of this, as he continued his military buildup, hoping that he could wage a sufficiently ruinous defensive war to force an Imperial withdrawal.

Sadly for him and Egypt-a Nile perch bone stuck happened to get stuck in his throat on an otherwise fine day in 996 and left the Caliphate to his mentally unstable eight year old son.

The regent was Al-Aziz’s eldest child, a woman known to us in the west as Sarah, but who Egyptians called Sitt al-mulk-a woman born to the Melkite mother who had been forcibly converted to the Coptic faith by Al-Aziz. Nominally a Copt, she had considerable pro-melkite sympathies, and a coup attempt by a Sunni general early on convinced both her and the Shia elite that some form of rapprochement with the Empire was needed. Direct vassalization was too humiliating, but anything short of that could be acceptable-leading them to send an emissary to Alexandria to ask for terms. Constantinople did not push too hard on the surface, only asking for an end for anti-Melkite persecutions and an increase in grain shipments. Secretly however, Basil drove a harder bargain-using the extra tribute to prop up Melkite leadership in Alexandria and feeding their flock for extra leverage. The Caliph was coerced to sign a document purely in Greek that effectively made him a vassal to the Empire by making him cede the title of “Defender of the two Holy Mosques of Mecca and Medinah” to Basil. In addition, governorships of key coastal cities like Pelusium were handed over to Melkites, who ruled most of those cities as Imperial clients than Fatimid officials.

No matter the steepness of price however, the landing of the tagma and four themes worth of troops in Alexandria under Nikepheros Xiphias put an end to Sunni rebellious thoughts. Egypt was not yet ready, and it would not be for years. For now the purple boots on their back could not be lifted, but the humiliated generals returned to their barracks seething, waiting for a day to come when they could avenge their honor.

Somewhat unexpectedly, a thirteen year old Sicilian guest of Al-Aziz would prove to be their savior.

Notes:

[1]: Through him, we observe the official hellenization policy of the Empire. It is telling that all the orphans were trained and educated at Aegean Islands, and most considered their earlier knowledge of Aramaic or Sicilian Latin to be a shame than a strength.

[2] This was no hyperbole, as it would be true till the advent of the printing press (in terms of literacy rate). Many farmers quickly found that learning Homer was a luxury their children had no need for once the funds for education dried up, leading to a decrease in overall literacy over time. Nonetheless, those who would move away from Anatolia to other parts of the Empire clung on to their culture even more tightly, and played a major role in hellenizing their societies.

[3] “Imperials”: A term originating from the semetic “melik” used to denote pro-Empire (i.e. Nicene-Chalcedonian) christians.

Vasilas’s notes

- Aqaba in Modern Jordan. Port on Red Sea.

- Originally a muslim, but a close enough friend of the Nestorian Patriarch to have survived the sack. Afterwards, Basil needed learned men-and cooperation was better than perishing.

Last edited:

The Caliph was coerced to sign a document purely in Greek that effectively made him a vassal to the Empire by making him cede the title of “Defender of the two Holy Mosques of Mecca and Medinah” to Basil. In addition, governorships of key coastal cities like Pelusium were handed over to Melkites, who ruled most of those cities into Imperial clients than Fatimid officials.

Holy shit, no doubt the rest of the house of Islam will raise hell over this, I honestly would think this would be more humiliating than direct vassalage. Now that the Empire has control over significant parts of the routes to the Holy Land and the Hajj is there the economic incentive to develop these areas to service the increased traffic that (peace?) will bring?

Holy shit, no doubt the rest of the house of Islam will raise hell over this, I honestly would think this would be more humiliating than direct vassalage. Now that the Empire has control over significant parts of the routes to the Holy Land and the Hajj is there the economic incentive to develop these areas to service the increased traffic that (peace?) will bring?

I just had the amusing thought. There are always contrarians in any situation. I wonder if we'd see a rise of "Melkite Islam" - i.e. Pro-Roman Islam that actually supports this. If they do exist - I wonder if it would facilitate the conversion from Islam to a version that Christians recognise as a Heresy. (Perhaps having Jesus as the Son of God, and Mohammed as the one to test the Vice Gerent of God - I dunno, choose your doctrine there).

It would be a massive socio-political change if it gained any level of prominence or dominance.

@All

I made one change to the previous update: Al-Aziz's son is eight, not eleven at the time of succession. OTL Al-Hakim (the loon this one is based on) was conceived in 985, right in the middle of the war with the Empire TTL, when daddy dearest was in the Levant. So we can butterfly that, and delay birth to 988-post peace. An unstable eight year old means a longer regency, making things work out better from TL perspective.

There is increased Jerusalem traffic from Europe, and the maritime republics+enterprising Greeks are capitalizing on it. This was partly the reason for the Provencal intervention-to open up some ports in southern France for Greek "travel-agencies" for a quick transfer to the Levant. The Hajj on the other hand.... Well, Western Islam is choosing to take the land route through Egypt till the Red Sea, while the Persians etc are sailing around Arabia. Romans are not exactly too welcoming.

I made one change to the previous update: Al-Aziz's son is eight, not eleven at the time of succession. OTL Al-Hakim (the loon this one is based on) was conceived in 985, right in the middle of the war with the Empire TTL, when daddy dearest was in the Levant. So we can butterfly that, and delay birth to 988-post peace. An unstable eight year old means a longer regency, making things work out better from TL perspective.

Actually, the treaty is a secret treaty. It was never ultimately exposed OTL in a time that mattered, and was only discovered centuries later in the archives. The update gets a bit of the chronology wrong (since TTL historians have no primary sources that even mention this treaty): Xiphias first landed in Alexandria, assisted the Fatimids in crushing the rebellion (mostly by preventing any uprisings in the delta while the actual Egyptian army sorted this out) and then forced the treaty down. It was supposed to be insurance-if the Caliph becomes less cooperative after the pro-Roman regency ends, the treaty could be exposed and him subsequently deposed by angry Sunnis. This Chekov's gun however does not go off.Holy shit, no doubt the rest of the house of Islam will raise hell over this, I honestly would think this would be more humiliating than direct vassalage. Now that the Empire has control over significant parts of the routes to the Holy Land and the Hajj is there the economic incentive to develop these areas to service the increased traffic that (peace?) will bring?

There is increased Jerusalem traffic from Europe, and the maritime republics+enterprising Greeks are capitalizing on it. This was partly the reason for the Provencal intervention-to open up some ports in southern France for Greek "travel-agencies" for a quick transfer to the Levant. The Hajj on the other hand.... Well, Western Islam is choosing to take the land route through Egypt till the Red Sea, while the Persians etc are sailing around Arabia. Romans are not exactly too welcoming.

See also https://www.alternatehistory.com/fo...ii-to-the-present.392656/page-4#post-13020275 . Rumi Islam will be a thing, facilitated by the Sicilian elites that cooperated with the Empire. But that will take centuries-the current administration is too rabidly anti-Muslim for that.I just had the amusing thought. There are always contrarians in any situation. I wonder if we'd see a rise of "Melkite Islam" - i.e. Pro-Roman Islam that actually supports this. If they do exist - I wonder if it would facilitate the conversion from Islam to a version that Christians recognise as a Heresy. (Perhaps having Jesus as the Son of God, and Mohammed as the one to test the Vice Gerent of God - I dunno, choose your doctrine there).

It would be a massive socio-political change if it gained any level of prominence or dominance.

I did not make it that far last time-but the Turks are coming. Not for almost another half-century, but coming.My memory of the previous TL is hazy but will there be any Turkic invaders coming in from the East? The Muslims in the East are not viable rivals and the Empire really needs a powerful foe to keep them on their toes and not get complacent after stomping everyone.

I may have missed it but how much is a theme's worth of troops? I expect that due to superior organisation the Empire is capable of producing much higher quantities (and quality) of troops on a much shorter notice than any of their neighbors.

I am actually not completely sure in OTL terms (themes probably had different numbers depending on location and population) and hence I used that wishy-washy description. For TL purposes the total number is something like just 10k thematic troops (themes not completely back to full strength either, and most were from west anatolia where the main recruitment focus is tagma driven). In general, the Empire can raise more manpower than other rivals due to superior organization, but the quality of a lot of the conscripts leave a lot to be desired. Professional tagma or orphans are inevitably what they actually want, with the rest just being cannon fodder.

1006-1008: Into the Twilight

Chapter 6: Into the Twilight

Auferre, trucidare, rapere, falsis nominibus imperium; atque, ubi solitudinem faciunt, pacem appellant.

To ravage, to slaughter, to usurp under false titles, they call empire; and where they make a desert, they call it peace.

Tacitus.

The Basilian renaissance continued for eighteen years from the end of the Sicilian war in 988 till the crisis of 1006. For almost a generation the Empire had effectively known peace and its inhabitants never had it so good. The Emperor and his men had built a land fit for heros who had toiled to restore the glory that was Rome, and it seemed like the future was bright. Until it all came crashing down in the middle of 1006 as the Empire descended into a crisis of scope unmatched after the seventh century, with even its prized Anatolian fortress breached.

The crisis was not created overnight, but had essentially been on the making since John Tzimiskes died and ceded long term planning for the Empire to Basil. Consumed with an overriding interest in domestic affairs and believing the Egyptian issue to be mostly settled, Basil made structural changes to the Imperial army which rendered them weak in the face of a truly devastating crisis. He reduced the size of the western anatolian thematic armies, seeing the probability of a land invasion in that region to be essentially null, while creating a larger professional tagmatic core which the Empire was loath to put to full use due to the extra active duty bonus promised to the soldiers. Simultaneously, no attempts were made to reorganize the Levant into proper themes-most cities had a large city guard drawn from Levantine Christian ranks charged with keeping order, with some Imperial garrisons in places like Antioch, Kaisaria and Gaza. No serious attempts to recruit an army from the countryside was made, and local disturbances were mostly settled with the aid of Arab auxiliaries the Empire paid. Their loyalty had always been questionable, but Constantinople felt that they did not represent a threat by themselves.

There were also no attempts made to intervene in the German civil war, or indeed-anywhere in Italy north of Benevento. The civil war had raged for long, but it finally ended in 1002 with the crowning of Henry of Bavaria as Emperor. At first Henry had attempted to negotiate about Italy with Constantinople, but was coldly rebuffed by Basil, who declared that there was only one Emperor of the Romans (conveniently forgetting his own brother for the time being). Incensed, the German started to look south across the Alps for support. The papacy and many other lombard princes had broken away from the German Empire during the civil war, but Henry would soon be in a position to amend that-Constantinople be damned.

Armenia was another great strategic blunder for the Empire. There had been a general migration of peasants from the poor lands to become laborers in the sheep farms of the east anatolian dynatoi, which the local princes had tried to curb. Far from assisting them in the attempt to curb the dynatoi-Basil had taken it as a personal affront and intervened militarily there from 994-1006, forcibly vassalizing many of them. It might have been acceptable had he merely stopped there, but he also left behind an annual tax bill for the Armenians to fill, alongside some bureaucrats to ensure that his will was carried out. Low level insurgency began almost immediately, but was stamped out by force. The Emperor felt confident enough at the time to even force many of the princes to will their domains to the Empire in the absence of direct heirs, seeing this as a chance to expand without significant loss of blood and treasure.

The greatest mistake however was Egyptian policy. The attempts of the Caliphate to seek Imperial protection from its Sunni masses were reciprocated strongly. Perhaps too strongly, as the Empire openly sent forces to assist the Shia elite in quenching a revolution and ordered their elaborate spy network (built over the past years) to assist the government, thereby compromising it completely. They tied themselves too strongly with the regency council and civil government while ignoring the army and the masses, who grew to resent the overt and strong Greek influence. Sending tutors for the Caliph proved to be the last straw for many of the Ulema and the other religious leaders, who started looking for alternatives and soon found one in the form of a certain Dawd. Dawd was the last known survivor of the Kalbid family that had previously ruled Sicily, and was a close friend of the young Caliph (who admired the martial prowess of the elder male). Dawd was too young and not particularly hostile to the regents to have been deemed a threat (though some might have sought to use him as a counter weight against Sitt Al mulk in the future) and he passed undetected by the channels used by the Empire to detect issues. A Fatimid officer later admitted that the spies originally hired by the Empire had long reported that he was a potential problem, but no one in Cairo had taken it seriously or had reported it to Alexandria. Dawd in the interim used his time to build connections to both the Sunni leadership and the army, now mostly made of children from Levantine refugee families.

The final problem of the Empire was strictly an internal one related to succession. Basil II had two male children-John and Michael, but neither were fit to rule. The former was drunkard who raged and swore at all weaker than him but cowered before his father, while that latter thought with his sword and lacked natural intelligence. Constantine VIII also did not have any male children, leaving the pool of potential successors narrow. In despair, Basil had forced a marriage between John and Constantine’s daughter Theodora, with that incestuous union resulting in a son called Basil in 998, but the couple despised each other and further progeny seemed unlikely. Recognizing that his focus on governance had led him to neglect his children to their detriment, he decided to not repeat the error and had his grandson brought to him at the age of five so that he could learn the art of ruling from his grandfather. Nonetheless, the Empire lacked an unambiguous successor to Basil in the early years of the eleventh century, raising the potential possibility of a coup that frightened some members of the Imperial family.

These unseen burdens weighed heavily on the Empire as the year 1006 arrived. Andronikos Doukas, the Imperial ambassador to the Fatimid Court, felt sufficiently comfortable in the Egyptian situation to request leave from his post to travel to China with a Fatimid embassy. Basil saw no issues in granting this request, and Doukas summarily left with the monsoon winds, promising to spread the word of the Empire all over the east. Meanwhile Basil personally went to tour Armenia and Mesopotamia along with his son Michael and grandson Basil, helping pacify a few problematic regions with lots of blood and fire. It was at this time when his eldest son (confined to Bari as nominal Katapeno) decided to create trouble by intervening in a papal election. The previous pope had done a fine balancing act between Basil and Henry, but Katapeno John was determined to please his father by bribing an unabashed pro-Constantinopoltan priest to power. The outraged opposition called upon the eager Emperor Henry, who marched over the Alps with a small army that rapidly swelled with Lombard support soon after entering the peninsula. Rome fell rather promptly and the Pope fled to his master at Bari (while a more pliant successor crowned Henry as Emperor of the Romans). Henry demanded that the errant Bishop be handed over, and John in a fit of pride refused-asking his father, the true Emperor of the Romans to intervene. An annoyed Basil complied, since drunkard or not-John was blood and could not completely be abandoned against a barbarian pretender. Henry on the other hand had expected similar behavior, and prepared for a long campaign to free Benevento and Salerno by driving the Greeks down to Apulia and Kalabria. Against him was arrayed the forces of Kuropalates Samuel of Sicily, while Emperor Basil himself sailed from Alexandretta to Italy, accompanied by his grandson, six thousand tagmatic troops and a large number of eastern anatolian thematic troops (expressly for the purpose of saving costs by not having the full tagma on active duty).

Italian geography from OTL

The Emperor’s departure right before winter was met with joy by the opposition in Egypt. They struck soon after, knowing that the Emperor was unlikely to risk winter storms and sail back. Sitt Al mulk and the rest of the regents were murdered, though not before some had squealed and exposed the complete Roman intelligence network in Egypt. That was quickly neutralized, and consistent false information sent to Alexandria to give an impression that all was well. Indeed, Nikepheros Xiphias would not have realized that anything was wrong till a survivor begged to be let in, being chased by a non-trivial portion of the Egyptian army. By then it was too late to reverse the situation, for the mentally unstable Caliph was no longer in actually in charge, having been replaced by the Wazir Dawd who called for an invasion of the Levant-seeing that to be the only leverage to hold over the head of the Romans who would soon attack the Nile delta with their navy. The Egyptian army (with a large chunk of Makurian slave soldiers) was summarily gathered and sent East, crushing the defenses of Gaza and being joined by many Bedouin tribes formerly allied with the Empire who saw this war as a chance to gather more loot. Kaisaria, Tyre, and other coastal fortresses steeled themselves, but the blow never came. Dawd had been focussing on the interior, and by January 1007, had been able to seize Jerusalem.

The Empire had been slow to realize the depth of the problem, and Empress Helena at first did not even inform her husband of the trouble, thinking that sending the remainder of the tagma to Egypt to remind the Caliph who was the boss would be adequate. The fall of Jerusalem radically changed the nature of the problem as it was too big a news to be contained. There was an immediate need for a major levantine force to be sent as well and the Empire scrambled to gather enough men from west anatolia and the balkans to make a push there. Some watered down reports were sent to Italy to assure Basil that the situation was firmly in control. That changed when Armenia rose in rebellion, seeing this as the perfect chance to force the Empire to listen. Prince Michael and his forces were in Nineveh at the time, and were completely cut off from the rest of the Empire into a Mesopotamian exclave, as the Armenians overran east anatolia. The dynatoi had depopulated the land for long, and most of the thematic troops were with Basil in Italy, resulting in no effective resistance as the countryside was raided-with some making it as far as the outskirts of Ancyra. Constantinople’s immediate response was paralysis, as plans of drawing soldiers from the balkans was immediately put on hold in the fear of an equivalent Bulgarian uprising (unfounded as the treatment there was much milder). The levant was forgotten as desperate levies were raised from the Aegean to send to Trebizond under the leadership of old Nikepheros Ouranos in order to contain the Armenian issue, complicated by the onset of winter. Dawd capitalized on the chaos as well, moving to seize Damascus and Aleppo that summer, further jeopardizing the situation of the Empire in the Levant. The coastal strip still held firm, but not much else.

Till then it was possible that the Egyptians were merely making temporary conquests as a show of strength to ultimately force minor concessions. But the Armenian crisis convinced Dawd that an opening had come to not just drive the Empire out of the Levant, but to actually conquer it outright. It is unclear whether his delusions of being a second, successful Muawiyah (as attested by Persian writers of the era) stemmed from from this period or not, but he certainly made moves consistent with such ideas by calling upon Arabia to provide him with ghazi warriors on his own authority as the lord of the old imperial city of Damascus and not in the name of the mad Caliph Al-Hakim. Al-Hakim was certainly not protesting at the time, praising Dawd for his victories and pulling men off the fields to supply more men for an Anatolian invasion.

Meanwhile in Italy, Basil had come extremely close to abandoning the peninsula completely after he had heard of the fall of Jerusalem, but was persuaded otherwise by Samuel to wait and engage the Germans once before calling for peace. The Armenian rebellion however complicated the whole issue as the anatolian soldiers were agitated about the fate of their homes. Basil and Samuel were left with no choice other than a march northwards to Capua in order to face Henry. The German Emperor had not been doing too well either-for the news of the second fall of Jerusalem had shaken Rome up heavily. The deeply pious Pope Stephen was openly wondering if this was divine retribution for Christendom fighting against itself, and if he had worsened the situation by dragging the Papacy into temporal politics. Lombard support was slowly melting away, and Henry knew he needed a victory. A quick decisive one was all he wanted, after which he would accept an apology but would not demand territory from the Greeks and let them go east. The two sides thus wound up clashing close to Rome itself in June 1007 and the outcome was not even close. It was a decisive German rout with Emperor Henry himself falling captive. Future western chroniclers uniformly described that God had raised the Greeks to unforeseen fury and had made Germans timid for their sin in letting Jerusalem fall. Those are obvious exaggerations with little rational basis, and I am more inclined to believe in the Imperial accounts that credit the tactical genius of Basil and Samuel in dealing a second massive German defeat in Italy, but perhaps some measure of guilt had harmed Latin morale and made their defeat to the enraged Greeks a bit more likely. Whatever the reason, Basil marched his army to Rome to find that Bishop Stephen had hanged himself in shame and there was no one ready to oppose the formerly deposed Pope John. Placing Samuel in charge of Rome, Basil immediately headed back east to Alexandria to determine the next course of action.

En route in Crete, he learned that Empress Helena had herself left the palace to handle the Armenian crisis, and had been mostly successful in containing it. The combined forces under her and Nikerpheros Ouranos’ command had held the Armenian raids from penetrating Anatolia any more, and they planned to winter in Edessa before launching a proper attack into Armenia proper to link up with Michael stuck in Nineveh. Michael was barely fending off Arab attacks from the south, (protected only by Dawd’s lack of interest in him for the moment), but their combined forces ought to be enough to handle the Armenians. Though somewhat horrified to know that his wife had gone to war on her own, Basil did not order her to return (as that would fatally undermine her position) but instead fired off instructions to Constantine VIII in Constantinople to drum up diplomatic support for them, by asking for assistance from Hungary, minor Balkan powers, Provence and the Rus. No one in the government realistically believed that Dawd had a legitimate shot taking Anatolia with the forces Ouranos and Helana commanded being there, and thus moving on to Egypt was for the best. There was an expectation that Antioch and the Levantine cities were doomed in the short term, with ships being stationed to evacuate as many people as possible to Cyprus, but the situation would be reversed after Egypt itself was taken down, which was almost guaranteed once Basil combined his forces with Xiphias’.

Edessa's position. It is possible to side step the city, but it leaves any army invading Anatolia running the risk of the Edessan's striking from the rear.

Dawd on the other hand was completely unwilling to get involved with any coastal settlement until he had a navy of his own, and was determined to take Anatolia down. It was this single minded focus that ultimately spared the coastal strip from a massacre of extraordinary proportions-for by spring 1008, no single person identifying as Nicene-Chalcedonian could be found alive outside Roman enclaves, having been massacred brutally by Dawd’s men who had in many cases been expelled from the same lands not too long ago. The fate for the converts from Islam had been the most brutal, with mass live incineration of apostates being described by Persian authors. This brutality however cemented Dawd’s position as the top dog in the region (in much the same way Basil’s Baghdad atrocities had for him), and allowed him to put together a 50,000 strong army for invading Anatolia by linking up with the Armenians. The Coptic contingent in his forces had made contact with the Armenians and were coordinating an invasion together. The forces in Edessa were the major obstacle on the road, and Dawd determined that it must first fall.

Here his miscalculations about the geography of the region became catastrophic. As a denizen of warmer climes, he decided that a winter attack was what the Empire was least expecting and were unlikely to respond properly to it. The Armenians tried to dissuade this madness, but ultimately fell in line, recognizing that Edessa contained the forces most likely to be a direct problem to them should Dawd not be there, and there was a chance that it would indeed fall and open Anatolia up for a spring campaign. Thus a fifty thousand strong Egyptian army coupled with fifteen thousand Armenians camped outside Edessa in November 1007, waiting for the city to give way.

It however ended exactly as anyone who knows geography could have predicted: there was simply not enough fuel to keep the combined army warm, and the Armenians were getting frustrated with Dawd’s demands for resources for his army as hypothermia started taking its toll. They attempted to sneak away after two weeks of siege only to be caught by the Egyptians, who attempted to restrain them by force. Ouranos and Helena led the forces in the city (themselves running low on food and fuel) in a major sortie to break up the besieging horde amidst their civil war, and succeeded with minimal casualties. The besieging horde was broken, with some Armenians escaping back their highlands to flee for Persia in spring, while Dawd retreated back to Damascus with only ten thousand men left, barely avoiding Michael who was rushing to Antioch from Nineveh while Dawd seemed distracted. The one major casualty on the Imperial side was Empress Helena herself, who had gone out to encourage her soldiers but had her horse throw her off in a moment of chaos. Her spin broken, she was paralyzed from waist down and was immediately sent back to Constantinople by a furious Ouranos, but the battle had been won. Anatolia was safe from the Arabs, and will be in perpetuity.

In Egypt meanwhile Basil and Xiphias had finally been able to break out of the delta by November and had besieged Cairo, when news of a new problem arrived. Caliph Al-Hakim had gone on a conscription spree first for Dawd and then to oppose Basil, without regard for the Egyptian economy. Large numbers of fields in upper Egypt lay unharvested, leading to a general food crisis all throughout Egypt. The Imperial attack had seriously disrupted cultivation in the delta, and even the Melkites were only holding out by virtue of Scythian grain sent by Prince Vladimir of Kiev. Reserves from granaries had already been sent to to the levant, leading to a general onset of famine. A bigger crisis however brewed in a village in upper Egypt where all the villagers had been killed for resisting the Caliph. The crop was in the field for the animals to feast, including a certain grasshopper that eagerly reproduced and expanded its numbers on the bounty.

After a certain while the population density was sufficiently high to swarm, and a seemingly biblical size locust horde rose towards the delta to pass judgement on Egypt. The fall of Cairo and execution of Al-Hakim thus proved to be far less a problem for Basil than this new menace. The horde ultimately did not cross the mediterranean but did dealt a considerable amount of damage to Egypt, already stressed from the war and forcible seizures. The southward advance by the Empire revealed no further resistance, only fields and villages of corpses bleached white by the ravenous insects. The Fatimid Caliphate had turned into a massive graveyard in its final days, while most of its men of fighting age lay dying outside the walls of Edessa. The Zirids were quick to take advantage of this by pouncing into Cyrenaica and only stopping when they met Imperial forces, quickly agreeing to partition the land between them. Makuria on the other hand could barely intervene since some fraction of the swarm had turned south and had devastated its lands, forcing them to handle their crisis and not be able to stop the Empire before Theophylact Botaniates reached the southern borders of Fatimid Egypt and had claimed it for Basil.

Meanwhile an Imperial army had landed in Kaisaria, consisting of the Orphans and a Varangian host sent by Prince Vladimir of Kiev, alongside all the palace guard Constantine VIII could find. Their mission was to cut off the retreat of the Egyptian host from the south, and they were extremely delighted to know that most of their work had already been done outside of Edessa. The strategos Alexander Komnenos decided to head north to Damascus to face the problem once and for all. Dawd had made it to Damascus with only five thousand men with him, but he had called on the last reserves and stripped the city of all men to have a twenty thousand strong host he was trying to retreat to Arabia with. The two armies faced off in an old field of battle, close to an infamous river.

Yarmouk.

The muslims were cheerful at last, for they had faced their enemy in the most favorable terrain possible, where Allah had once granted them victory over the infidel once before. The Romans however stood expressionlessly, even though the significance of the place was not lost on them.

The palace guard waited unhesitantly, ready to serve their Emperor one final time at the hour of greatest need.

The Orphans did not flinch, for this was the moment they had been praying for all their lives.

The Varangians did not show fear, with the fanatical zeal of the new convert that would have likely impressed Khaled himself.

Six times the Arabs charged south and six times the Romans held steady.

On the seventh time the northerners saw their ranks break and the survivors fled across the desert, with some supposedly making it to Persia. Only then did Alexander Komnenos smile, for his forces had finally broken the deadliest enemy the Empire had ever faced (irreversibly, though he did not know it).

The official history of the Orphans assures us that his first words after the battle were “And next year in Mecca!”.

Dawd's corpse was never found , though the Orphans assure us that he died. There are claims in Persia though that he managed to make it there, and died an old man advising the Turks, though this is not supported by any hard evidence.

Last edited:

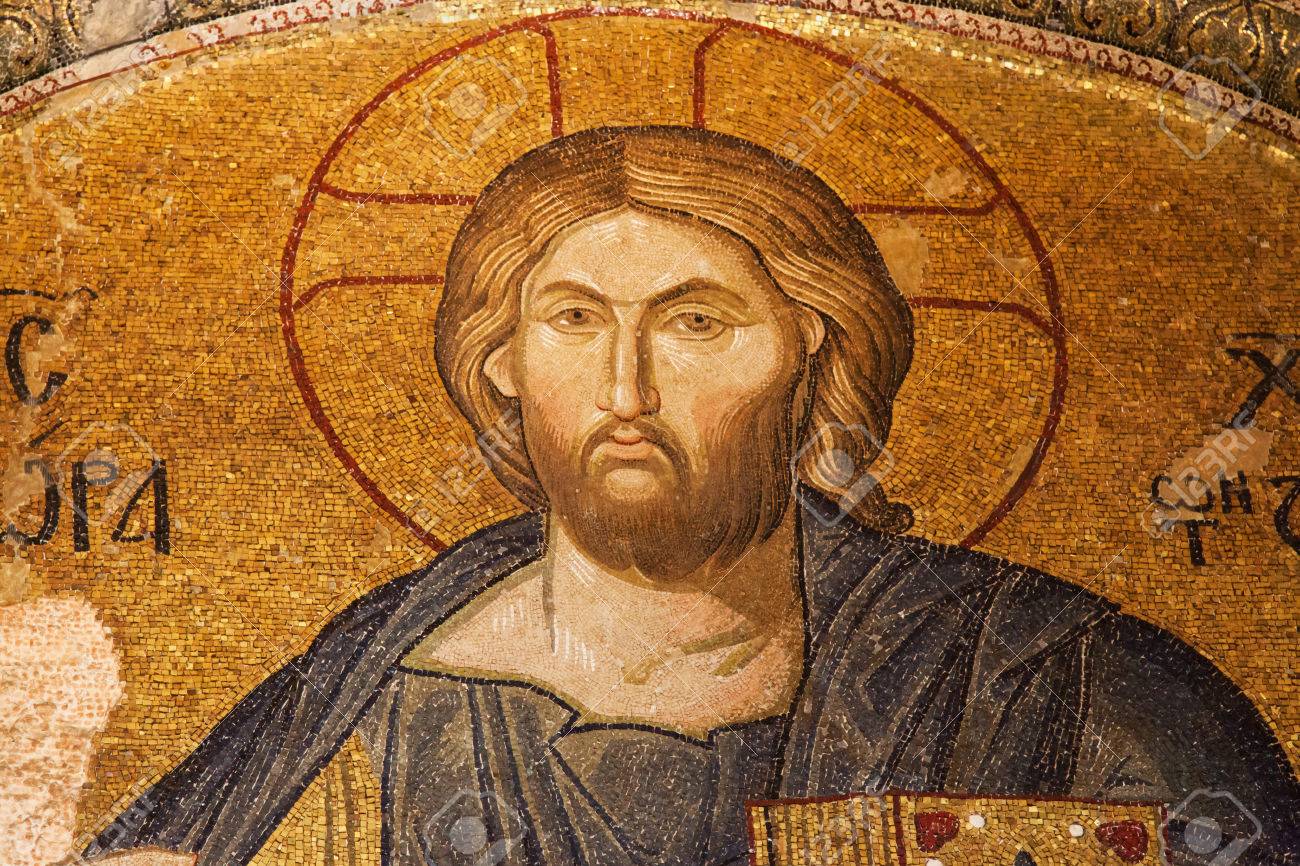

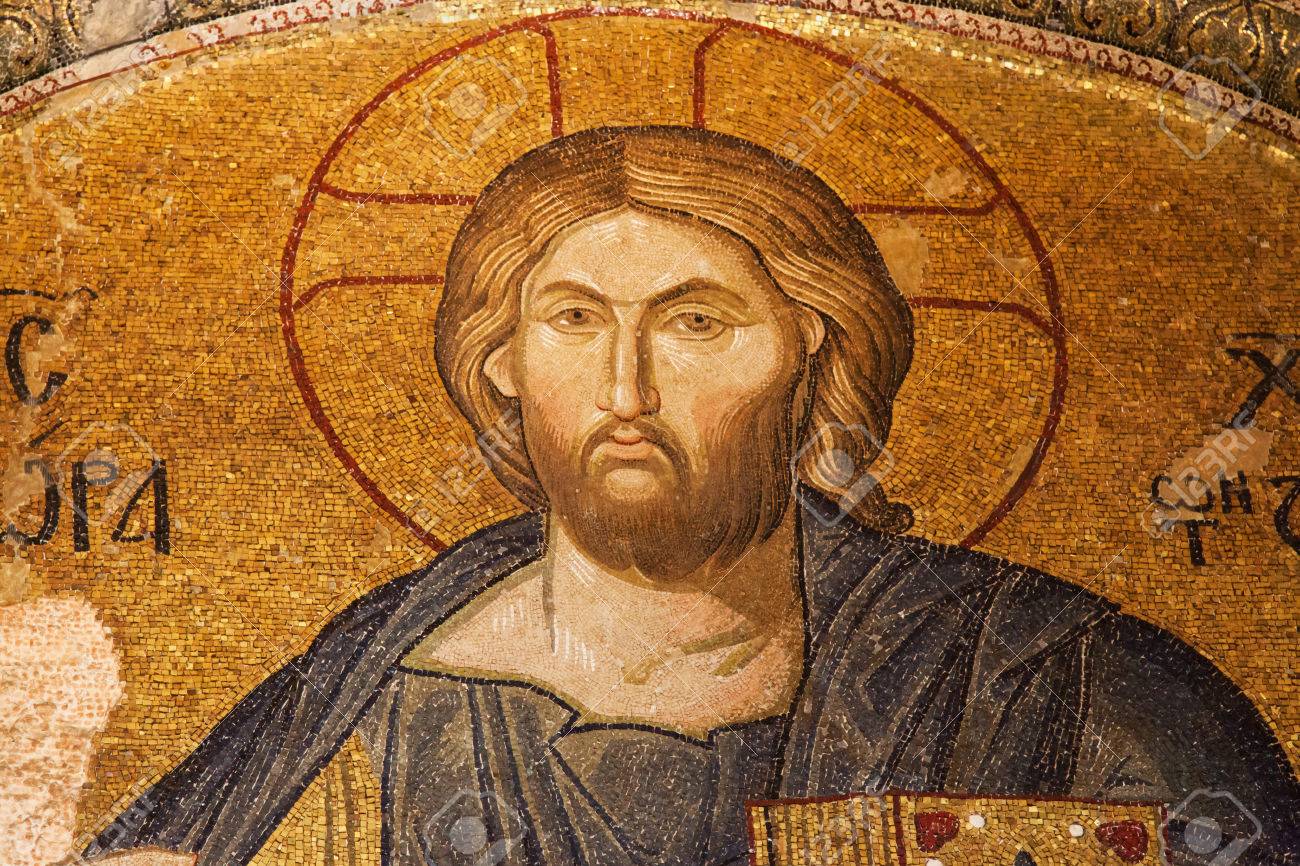

Hope everyone has a good time on the supposed birthday of the most famous Byzantine figure there is!

Ἰησοῦς Χριστός ( 4 B.C.- 33 A.D.)

βασιλεύς τῶν Ῥωμαίων (312 A.D.-1640 A.D.)

The Roman Empire had extremely high social mobility-as made evident by the many common farmers and soldiers who had made it to the purple. The best example for this of course is Jesus of Nazareth-an ethnic Jewish carpenter who likely did not know any Latin or Greek, and attempted to lead a rebellion against the Roman Empire only to wind up dead on a crucifix. Death however did not prevent him from becoming Emperor in 312 A.D. under the graces of Constantinos Isapostolos, and he continued to rule over the Empire through a variety of lesser viceregents until theocratia came to an end in 1640. There is however an entire modern political party devoted to restoring him back to his Imperial office, and so do not be surprised if he returns back to a position of power anytime soon.

Ἰησοῦς Χριστός ( 4 B.C.- 33 A.D.)

βασιλεύς τῶν Ῥωμαίων (312 A.D.-1640 A.D.)

The Roman Empire had extremely high social mobility-as made evident by the many common farmers and soldiers who had made it to the purple. The best example for this of course is Jesus of Nazareth-an ethnic Jewish carpenter who likely did not know any Latin or Greek, and attempted to lead a rebellion against the Roman Empire only to wind up dead on a crucifix. Death however did not prevent him from becoming Emperor in 312 A.D. under the graces of Constantinos Isapostolos, and he continued to rule over the Empire through a variety of lesser viceregents until theocratia came to an end in 1640. There is however an entire modern political party devoted to restoring him back to his Imperial office, and so do not be surprised if he returns back to a position of power anytime soon.

Last edited:

So the Egyptians are defeated through a combination of General Winter (Of a minor scale), Moses' plague, and good old fashion Roman martial superiority. Great update!

Does this Alexander Komnenos have any relation to any OTL people?

Does this Alexander Komnenos have any relation to any OTL people?

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Share: