You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

These United Provinces: An Argentine TL

- Thread starter FossilDS

- Start date

A special thanks to everyone who commented on this thread: https://www.alternatehistory.com/fo...-wi-strong-united-provinces-argentina.398843/ for giving me some great ideas:

My timeline attempts to explore if Argentine Governor Manuel Dorrego had not acted on impulse, and instead fled during the Decembrist Revolution. This is my first TL, all criticism is appreciated. I intend to focus heavily on Argentina/United Provinces first, then branch out into different parts of the world. If you are lost, read below to the introduction.

I hope you all enjoy!

Introduction

December 13th, 1828. Navarro, United Provinces of the Río de la Plata. (modern day Argentina). OTL.

The humidity clinged tightly to his uniform.

He had walked up to the firing squad without fear, but a tinge of regret in his eyes. He knew that there was still so much to be done. The soldiers, not wanting to spend another minute in the sweltering summer heat, quickly started loading their muskets: old Spanish models, from the War of Independence.

The black powder was loaded into the muzzle. Then more powder was loaded into the pan, the hammer cocked and the single projectile dropped into the barrel . After what seemed like an eternity, they were ready to fire.

A younger man, with an impressive beard and an ostentatious military uniform to match signifying his rank as a general, order the troops the present thier weapon. Then to fire.

That moment, eight shots peppered the condemned man’s chest. He was dead within an instant.

His former friend, Gregorio Aráoz de Lamadrid, watched grimly. In his pocket he carries the man’s last letters: addressed to his wife and two young daughters.

Manuel Críspulo Bernabé Dorrego was dead. And the young Argentine nation would be plunged into darkness….

...

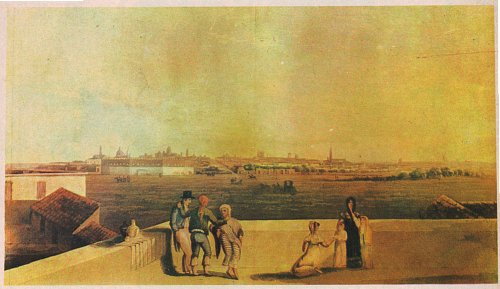

...The population of what is now Argentina steadily grew, and in the 1700’s, the land now Bolivia, Argentina and Paraguay became the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. Although the new viceroyalty possessed a massive natural harbor in the form of the Río de la Plata, the Spanish chose to ignore it and conduct all trade out of Lima. Contraband became the main source of revenue , and slowly the viceroyalty started to seethe with resentment.

The British, taking advantage of the Peninsular War, invaded Buenos Aires, the new capital of the Viceroyalty, with elite veterans of the Napoleonic Wars. Calls for help fell on deaf ears in Spain. However, the ramshackled criollo militias successfully repelled the British invasions. The fact that untrained, citizen militias had repulsed British professional soldiers without any help from Spain further heightened tensions. Finally, on May the 25, 1810, the cabildo of Buenos Aires resolved to overthrow the Viceroyalty and declare a self-governing Junta, or council. The Primera Junta (First Junta) broke down, but new ones quickly replaced it. With the end of the Napoleonic Wars some five years later, an alarmed Spain sent forces to crush the Junta.They were soundly defeated, and in 1816 the Junta declared independence from Spain as the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata, comprising of the whole of the former Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. However not even an year into the United Provinces’ existence, the country fragmented, as the question whether to form a conservative federation or a liberal unitary state had divided the populace. The Federals and the Unitarians would fight a civil war for four years. In the chaos, warlords, called caudillos, carved out the provinces as their personal fiefdoms.

The Unitarians were defeated at Cepeda in 1820. The Federals and the Unitarians tried to mend their differences and a appoint a committee to write a new constitution for the whole nation. The resulting constitution, which was regarded as too Federals by the Unitarians and too Unitarian for the Federals, collapsed on itself in less than two years. As a result, the then-President Bernardino Rivadavia resigned, with no one to succeed him. The country, with no official head, fell into chaos yet again. The then-governor of Buenos Aires took over foreign affairs. The governor’s name? Manuel Dorrego.

Dorrego was the headstrong son of a Portuguese merchant who as a young man fought for the independence of the United Provinces. Dorrego was an avowed Federal, but also paradoxically supported liberalism when the Federals were overwhelming conservative. A promising leader, he was elected as Governor in 1827, at age 40. However, he botched a peace treaty with Brazil and caused a Unitarian-backed mutiny, which he fled to the countryside. He had planned to flee to a neighboring province and gather reinforcements, but changed his mind at the last moment and fought at the small village of Navarro. He predictably lost and promptly was executed.

Dorrego was avenged, but by a very different sort of leader: Juan Manuel de Rosas. Rosas defeated Lavalle and the rebellious interior provinces, and reformed the United Provinces into the first rendition of modern Argentina: Argentine Confederation.

Rosas was a charismatic, agreeable, blond hair, blue eyed landowner fron Buenos Aires. Nevertheless, he had a dark, tyrannical streak under this facade. Rosas, although a Federalist, was a megalomaniac who curtailed provincial autonomy a struck terror into the hearts of his opposition.Rosas formed one of the world’s first parapolices, the Mazorca, which killed thousands opposed to his rule for trivial or even nonexistent offences. De Rosas pushed Argentina into crippling wars and into underdevelopment. The extent of Rosas’ megalomaniac rule was so absurd it was almost farcical. Every document had the heading "Death to the Savage Unitarians!” and every male was required to have “Federalist” look: sideburns with a large mustache. Every state apparatus was reduced to rubber stamps subservient only to him. Rosas was a slave-owner, and the slave trade experienced a revival.

Finally, after a combination of a disastrous war with Brazil, a joint British French blockade and a massive internal revolt, The Rosas regime finally collapsed in early 1852. Rosas was gone, fleeing to a new sympathetic British government, but the damage was already done. Argentina was underdeveloped, in a civil war, and outcompeted by Brazil.

But what if Argentina never had a Rosas, or a protracted civil war?

What if?

Prelude

“My dear Angelita: At this point I intimate that within an hour I die. I do not know why; but divine providence, which I trust this critical moment, so wanted. I forgive all my enemies and beg my friends not to give any step in relief that has been received by me. My life educates these gentle creatures. I am happy, because you have not been accompanied by the unfortunate Manuel Dorrego.”

-Manuel Dorrego writing to his wife, Angelita, on the day of his execution. 1828. OTL.

From Lander’s World Cyclopedia, 4th Edition. (1978, Durrington Press, Hartford, State of Connecticut.)

DORREGO, MANUEL: (June 11th 1787- July 23rd 1867) Platense [1] statesman,soldier and writer who served as the third President of the United Provinces (1832-1840). Principal contributor to the Pacto Nacional (National Pact), and Platense Constitution of 1832, Dorrego would preside over the end of the Tercera Guerra Desunión (Third Disunity War), reform the fractious Federalist [2] Party into the Partido de la Federación, (Party of the Federation)...

...Dorrego, born on June the 11th, 1787, to wealthy Portuguese merchant Jose Antonio do Rego and his Platense wife Mary Ascension Salas, Dorrego was educated at El Real Colegio de San Carlos (Royal College of San Carlos), and later at Real Universidad de San Felipe (now the University of Chile). After he graduated with a degree in law, he was one of the first supporters of the May Revolution. Dorrego later joined the Army of Peru, and fought with distinction during the critical victories of Salta and Tucumán. Dorrego would be an early actor on the nascent Platense political scene, as an avowed Federalist. Exiled by his political enemy Juan Martín de Pueyrredón, Dorrego would live in the United States from 1816 to 1820. This would have important consequences on Dorrego’s life, affirming and inspiring his own Federalist views. Dorrego would return to the United Provinces with the fall of Pueyrredón. When returning to the United Provinces, Dorrego would publish a newspaper criticizing the ruling Unitarianist regime.A few years later, would embark on a trip to the north of the United Provinces, where he would meet El Libertador....

From The River of Silver: Dorrego, Federalism and the Early United Provinces by James Henry Derringer (1980, Darren University Press, Baltimore, State of Maryland )

When Dorrego arrived at Potosi on a cool July morning in 1825, he was nominally there to inspect her impressive (if somewhat depleted) silver and tin mines. However, it was no secret that what Dorrego’s main purpose in being at the Villa Imperial [3] was to meet a legend of a man: Simón Bolívar. Dorrego met El Libertador a month prior to the declaration of independence of Bolivia, at a ramshackled casita at the edge of the city. Bolívar was excited at the opportunity to meet someone from another liberated state, whilst Dorrego was just as enthusiastic to meet someone of such great importance. Although Dorrego was a Federalist and Bolívar a Centralist, the meeting left Dorrego deep and newfound respect for Bolívar. He would write letters praising El Libertador, feeling that he was the only man that could unite the disparate Latin American states against Brazil. Dorrego also absorbed some of Bolívar‘s philosophy about a united Latin America, in the sense that there must be a united front against imperialism. [4] This seemingly inconsequential footnote would have momentous consequences later on...

[1] TTL Argentine. Derives from the Rio de la Plata. The term “Argentina” will be later assigned to the Buenos Aires province.

[2] OTL Federales.

[3] Nickname for Potosi.

[4] The first of two POD with Dorrego. As in OTL, Dorrego meets with Bolivar and instantly takes a liking of him, but in TTL Dorrego adopts some of Bolivar’s philosophy… Also Dorrego and Bolivar meet in Potosi, not in Cusco as OTL.

My timeline attempts to explore if Argentine Governor Manuel Dorrego had not acted on impulse, and instead fled during the Decembrist Revolution. This is my first TL, all criticism is appreciated. I intend to focus heavily on Argentina/United Provinces first, then branch out into different parts of the world. If you are lost, read below to the introduction.

I hope you all enjoy!

Introduction

December 13th, 1828. Navarro, United Provinces of the Río de la Plata. (modern day Argentina). OTL.

The humidity clinged tightly to his uniform.

He had walked up to the firing squad without fear, but a tinge of regret in his eyes. He knew that there was still so much to be done. The soldiers, not wanting to spend another minute in the sweltering summer heat, quickly started loading their muskets: old Spanish models, from the War of Independence.

The black powder was loaded into the muzzle. Then more powder was loaded into the pan, the hammer cocked and the single projectile dropped into the barrel . After what seemed like an eternity, they were ready to fire.

A younger man, with an impressive beard and an ostentatious military uniform to match signifying his rank as a general, order the troops the present thier weapon. Then to fire.

That moment, eight shots peppered the condemned man’s chest. He was dead within an instant.

His former friend, Gregorio Aráoz de Lamadrid, watched grimly. In his pocket he carries the man’s last letters: addressed to his wife and two young daughters.

Manuel Críspulo Bernabé Dorrego was dead. And the young Argentine nation would be plunged into darkness….

...

...The population of what is now Argentina steadily grew, and in the 1700’s, the land now Bolivia, Argentina and Paraguay became the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. Although the new viceroyalty possessed a massive natural harbor in the form of the Río de la Plata, the Spanish chose to ignore it and conduct all trade out of Lima. Contraband became the main source of revenue , and slowly the viceroyalty started to seethe with resentment.

The British, taking advantage of the Peninsular War, invaded Buenos Aires, the new capital of the Viceroyalty, with elite veterans of the Napoleonic Wars. Calls for help fell on deaf ears in Spain. However, the ramshackled criollo militias successfully repelled the British invasions. The fact that untrained, citizen militias had repulsed British professional soldiers without any help from Spain further heightened tensions. Finally, on May the 25, 1810, the cabildo of Buenos Aires resolved to overthrow the Viceroyalty and declare a self-governing Junta, or council. The Primera Junta (First Junta) broke down, but new ones quickly replaced it. With the end of the Napoleonic Wars some five years later, an alarmed Spain sent forces to crush the Junta.They were soundly defeated, and in 1816 the Junta declared independence from Spain as the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata, comprising of the whole of the former Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. However not even an year into the United Provinces’ existence, the country fragmented, as the question whether to form a conservative federation or a liberal unitary state had divided the populace. The Federals and the Unitarians would fight a civil war for four years. In the chaos, warlords, called caudillos, carved out the provinces as their personal fiefdoms.

The Unitarians were defeated at Cepeda in 1820. The Federals and the Unitarians tried to mend their differences and a appoint a committee to write a new constitution for the whole nation. The resulting constitution, which was regarded as too Federals by the Unitarians and too Unitarian for the Federals, collapsed on itself in less than two years. As a result, the then-President Bernardino Rivadavia resigned, with no one to succeed him. The country, with no official head, fell into chaos yet again. The then-governor of Buenos Aires took over foreign affairs. The governor’s name? Manuel Dorrego.

Dorrego was the headstrong son of a Portuguese merchant who as a young man fought for the independence of the United Provinces. Dorrego was an avowed Federal, but also paradoxically supported liberalism when the Federals were overwhelming conservative. A promising leader, he was elected as Governor in 1827, at age 40. However, he botched a peace treaty with Brazil and caused a Unitarian-backed mutiny, which he fled to the countryside. He had planned to flee to a neighboring province and gather reinforcements, but changed his mind at the last moment and fought at the small village of Navarro. He predictably lost and promptly was executed.

Dorrego was avenged, but by a very different sort of leader: Juan Manuel de Rosas. Rosas defeated Lavalle and the rebellious interior provinces, and reformed the United Provinces into the first rendition of modern Argentina: Argentine Confederation.

Rosas was a charismatic, agreeable, blond hair, blue eyed landowner fron Buenos Aires. Nevertheless, he had a dark, tyrannical streak under this facade. Rosas, although a Federalist, was a megalomaniac who curtailed provincial autonomy a struck terror into the hearts of his opposition.Rosas formed one of the world’s first parapolices, the Mazorca, which killed thousands opposed to his rule for trivial or even nonexistent offences. De Rosas pushed Argentina into crippling wars and into underdevelopment. The extent of Rosas’ megalomaniac rule was so absurd it was almost farcical. Every document had the heading "Death to the Savage Unitarians!” and every male was required to have “Federalist” look: sideburns with a large mustache. Every state apparatus was reduced to rubber stamps subservient only to him. Rosas was a slave-owner, and the slave trade experienced a revival.

Finally, after a combination of a disastrous war with Brazil, a joint British French blockade and a massive internal revolt, The Rosas regime finally collapsed in early 1852. Rosas was gone, fleeing to a new sympathetic British government, but the damage was already done. Argentina was underdeveloped, in a civil war, and outcompeted by Brazil.

But what if Argentina never had a Rosas, or a protracted civil war?

What if?

Prelude

“My dear Angelita: At this point I intimate that within an hour I die. I do not know why; but divine providence, which I trust this critical moment, so wanted. I forgive all my enemies and beg my friends not to give any step in relief that has been received by me. My life educates these gentle creatures. I am happy, because you have not been accompanied by the unfortunate Manuel Dorrego.”

-Manuel Dorrego writing to his wife, Angelita, on the day of his execution. 1828. OTL.

From Lander’s World Cyclopedia, 4th Edition. (1978, Durrington Press, Hartford, State of Connecticut.)

DORREGO, MANUEL: (June 11th 1787- July 23rd 1867) Platense [1] statesman,soldier and writer who served as the third President of the United Provinces (1832-1840). Principal contributor to the Pacto Nacional (National Pact), and Platense Constitution of 1832, Dorrego would preside over the end of the Tercera Guerra Desunión (Third Disunity War), reform the fractious Federalist [2] Party into the Partido de la Federación, (Party of the Federation)...

...Dorrego, born on June the 11th, 1787, to wealthy Portuguese merchant Jose Antonio do Rego and his Platense wife Mary Ascension Salas, Dorrego was educated at El Real Colegio de San Carlos (Royal College of San Carlos), and later at Real Universidad de San Felipe (now the University of Chile). After he graduated with a degree in law, he was one of the first supporters of the May Revolution. Dorrego later joined the Army of Peru, and fought with distinction during the critical victories of Salta and Tucumán. Dorrego would be an early actor on the nascent Platense political scene, as an avowed Federalist. Exiled by his political enemy Juan Martín de Pueyrredón, Dorrego would live in the United States from 1816 to 1820. This would have important consequences on Dorrego’s life, affirming and inspiring his own Federalist views. Dorrego would return to the United Provinces with the fall of Pueyrredón. When returning to the United Provinces, Dorrego would publish a newspaper criticizing the ruling Unitarianist regime.A few years later, would embark on a trip to the north of the United Provinces, where he would meet El Libertador....

From The River of Silver: Dorrego, Federalism and the Early United Provinces by James Henry Derringer (1980, Darren University Press, Baltimore, State of Maryland )

When Dorrego arrived at Potosi on a cool July morning in 1825, he was nominally there to inspect her impressive (if somewhat depleted) silver and tin mines. However, it was no secret that what Dorrego’s main purpose in being at the Villa Imperial [3] was to meet a legend of a man: Simón Bolívar. Dorrego met El Libertador a month prior to the declaration of independence of Bolivia, at a ramshackled casita at the edge of the city. Bolívar was excited at the opportunity to meet someone from another liberated state, whilst Dorrego was just as enthusiastic to meet someone of such great importance. Although Dorrego was a Federalist and Bolívar a Centralist, the meeting left Dorrego deep and newfound respect for Bolívar. He would write letters praising El Libertador, feeling that he was the only man that could unite the disparate Latin American states against Brazil. Dorrego also absorbed some of Bolívar‘s philosophy about a united Latin America, in the sense that there must be a united front against imperialism. [4] This seemingly inconsequential footnote would have momentous consequences later on...

[1] TTL Argentine. Derives from the Rio de la Plata. The term “Argentina” will be later assigned to the Buenos Aires province.

[2] OTL Federales.

[3] Nickname for Potosi.

[4] The first of two POD with Dorrego. As in OTL, Dorrego meets with Bolivar and instantly takes a liking of him, but in TTL Dorrego adopts some of Bolivar’s philosophy… Also Dorrego and Bolivar meet in Potosi, not in Cusco as OTL.

Last edited:

Chapter 1: Divergences and Dorrego

“Dorrego, who had obtained the government through parliamentary opposition, now tried to win the Unitarios, whom he had conquered ; but parties have neither charity nor foresight. The Unitarios laughed in their sleeves, and said among themselves, ‘He totters, let him fall.’ ”

-From Facundo: Civilization and Barbarism (1845) by Domingo Faustino Sarmiento. OTL.

From The River of Silver: Dorrego, Disunion and the Early United Provinces by James Henry Derringer (1980, Darren University Press, Baltimore, State of Maryland )

When Dorrego returned from Montevideo at the conclusion of the negotiations which led to the signing of the Treaty of 1828,[2] he had not gained all of what he hoped for, but felt his course of action was the best possible for the fledgling United Provinces. Dorrego, as later recounted in his memoirs, had felt as if he had saved the United Provinces from “a war which would take away the sovereign rights of the people, and impose foreign domination and hardship on our peoples.” (Dorrego, uncharacteristically used caution avoided the term “British”.) Indeed, Dorrego had to be careful not to mention the inhabitants of the island of Britain, because he had been pressured into the terms by the none other than the John Ponsonby, a shrewd diplomat which had curtailed Platense ambitions of annexing the Cisplatine Province. Prior to this, almost every battle in the war was won by Platense forces. Although this prevented a cataclysmic conflict with the United Kingdom and Brazil, it had also turned the military against the nascent Dorrego administration. As a result, it was perceived by more than a few soldiers that Dorrego was a British puppet.

Therefore, it was a surprise to no one that the returning veterans hated Dorrego–everyone except Dorrego, that is. Dorrego had made the near fatal miscalculation that the military still supported him. The whole unfortunate episode might have been avoided if not for Unitarianist [3] officers who lambasted the Dorrego, the “British governor of Buenos Aires.” With all of the discontent, some Unitarianists were getting ideas...

On the evening of the 30th of November, 1828, a motley group of Unitarianist backed officers and politicians met in a stuffy house on Calle Jardín (Garden Street), owned by Reynoso Pabón, a Unitarianist. [4] In hushed whispers and nervous glances, they discussed plans to capitalize on the soldiers’ anger. Their opinions were diverse, but they had one thing in common: all agreed that Dorrego had to go. Some officers argued for more time to prepare for a coup which would depose Dorrego in a few months. Another faction headed by a certain Juan Lavalle, who was decorated for valour during the battle of Ituzaingó (Platense victory during the Cisplatine war). They called for immediate vengeance against the “backstabbing” Dorrego. After intense debate, Lavalle’s faction won out. The conspirators decided to hit when Dorrego least expected it: namely, the next day.

On December 1st, the conspirators put their plan into action. An estimated 400 Unitarianist troops stormed Plaza de la Victoria [4]and other units captured key choke points and landmarks throughout the city. Before daybreak, troops had already captured,with naval help, Fuerte de San Miguel (San Miguel Fort) [5], and the famed Buenos Aires Cabildo. Lavalle, declaring Dorrego illegitimate, held an “election” for governor: all the votes cast (there weren't many) were all for Lavalle. Dorrego, not expecting a revolt, was caught off guard by this sudden military coup, and fled to the countryside to build up a rural militia, joined by local native allies. In a few days, Dorrego managed to procure a forces numbering around 1,700. Calling Dorrego’s troops “inexperienced” would be a gross understatement: most of Dorrego’s ramshackled militia have never had a day of military training in their lives. Making matters worse, Dorrego was a brave but brash commander: an often deadly combination. Meanwhile, Lavalle was fielding an army of his own. Although numerically inferior, each one of Lavalle’s 600 soldiers were handpicked veterans of the late Cisplatine war. Dorrego worried for his family in Buenos Aires, planned to face Lavalle, even choosing a site for battle.(Records of the site of the planned battle have been lost, but it is thought to have been somewhere near Lobas, Argentina Province.)

However, he was dissuaded by a letter from the rising and controversial figure Juan Manuel de Rosas, which pleaded him not to fight Lavalle. Instead, Dorrego decided to march to Santa Fe [6] with his ragtag “army” with him. Dorrego made painfully slow progress to Santa Fe, but was supported by supplies from Rosas (the source of these supplies, are however questionable). Following the Paraná Basin, Dorrego’s troops faced ghastly roads, low food, and abysmal morale. In fact, Dorrego’s troops nearly mutinied until he made offers of pay and land when they defeat Lavalle. Thankfully, the terrain was mercifully flat, and on the morning of New Year's Day, 1829 , Dorrego arrived at a ford on the Salado River: the gateway to Santa Fe. He was greeted by Rosas, in full military dress. Rosas was striking as usual, with the blue eyes, a bulky build and infectious charisma. Rosas welcomed Dorrego in a hearty, if a little over the top ceremony. Privately, Dorrego harbored doubts about Rosas’ true personality, but kept to himself. After all, the important point was that Rosas had 7,000 men: 4,000 militia and 3,000 natives. Even though they are all of dubious quality, this was more than enough to beat Lavalle’s forces. When combined with Dorrego’s troops, the numbers swelled to 8,700, a formidable force numerically, if not in experience.

After a week of rest and planning, Dorrego and Rosas both decided to march upon Lavalle’s nascent military dictatorship in Buenos Aires. Lavalle, after a brief surge in popularity, had shown his true colors, and began bloody purges in Buenos Aires as well as the countryside. He had anyone who dared question him summarily executed, and began to alienate many of the plotters, including much of his powerbase: the veterans. The morale problems which plagued Dorrego during his march to Santa Fe now plagued Lavalle: the troops who had toppled Dorrego just a month ago, now were threatening to mutiny. Lavalle, seeing that if he didn't act fast, he could expect to be toppled by his own troops.Lavalle departed Buenos Aires on January 5th, Dorrego and Rosas on the 7th. It was only a matter of time before the two armies clashed and decided the fate of the United Provinces.

From: Repository of Military History, 3rd Edition (1965, Delmar Publishing, Dover, State of Delaware)

RÍO FEDERAL, BATTLE OF: (20 January 1829, Río Federal [7], United Provinces.) Battle between Federalist and Unitarianist forces during the Third Platense Civil War (Spanish: Tercera Guerra Desunión). Fought near the modern town of Río Federal(Spanish: River Federal ) in the modern day United Provinces, the battle was a decisive victory for Federalist forces.

BACKGROUND: Manuel Dorrego, de facto Federalist (faction favoring federation) leader of the United Provinces was ousted in a coup d'etat by Unitarianist ( faction favoring unitary state) forces. Dorrego and a small militia fled to Santa Fe, where they combined with larger Federalist army led by Juan de Rosas . Federalist Army totals 8,700 personal, consisting of 5,000 lightly trained militia , as well as gancho calvary, and 3,700 native allies. Federalist army leaves Santa Fe, seeking confrontation with Unitarianist forces. Unitarianist forces consist of 1,200 well trained veterans of the Cisplatine War led by Juan Lavalle. Forces clash at the ford of the River Federal, a tributary of the ,Paraná River, near the village of future village of Río Federal on the 20th.

EVENTS: Federalist commanders, sensing numerical superiority as well as higher morale, sets up an ambushes for Lavalle’s force on the ford of the River Río Federal. Lavalle’s forces cross the river at 6:00, only to be surprised by Federalist forces. Lavalle’s men hold their ground until 8:30, then crumble after waves of Gancho cavalry. Most of Lavalle’s forces, but not Lavalle himself, captured trying to cross the ford back to Buenos Aires.

AFTERMATH: Unitarianist resistance crumbles and Federalist troops triumphantly reinstate Dorrego in the capital of Buenos Aires. Dorrego’s decision not execute the prisoners as suggested by Estanislao López would have important consequences, as it...

....

ESTIMATED STRENGTH/ CASUALTIES

Federalists: 8,700, mostly untrained, with 1000 gaucho calvary / 200 WIA, 95 KIA

Unitarianists: 1,200, trained. /225 WIA, 200 KIA, 875 captured.

[1] Treaty of Montevideo 1828, which ended Cisplatine War OTL.

[2] TTL term for Unitarian.

[3] The conspirators met on November the 30th as per OTL, on a house on Garden Street, although “Reynoso Pabón” is invented.

[4] OTL Plaza de Mayo

[5] OTL Casa Rosa, official executive mansion of Argentina.

[6] Major POD. in OTL, Dorrego unexpectedly changed his mind and did battle in Navarro, which ended with him losing and getting executed.

[7] OTL Monje, Santa Fe.

Last edited:

Chapter 2: El Sol de la Libertad

“Perhaps also the death of Dorrego was one of those fated events which form the nucleus of history, without which it would be incomplete and unmeaning.”

-From Facundo: Civilization and Barbarism (1845) by Domingo Faustino Sarmiento. OTL.

“Ideas can not be killed"

-Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, OTL.

From Lander’s World Cyclopedia, 4th Edition. (1978, Durrington Press, Hartford, State of Connecticut.)

FEDERALISM (Platense political movement): A political ideology, party, and movement in the United Provinces from 1816 to 1835. Federalism stemmed from the ideas of the “outsider” provinces which were traditionally excluded from state affairs. Federalists advocated for provincial autonomy and a federation to bind together the United Provinces. Their stance on Buenos Aires’ lucrative customs tax caused resentment in the capital, which supported the Federalists’ opponents, the Unitarianist. This conflict would be exacerbated in the Primera Guerra Desunión, (First Disunity War), in which the Federalist League of the Free Peoples (Liga de los Pueblos Libres) would be paired against the heavily Unitarianist Supreme Directorship. In this war, the Federalists would triumph in the battle of Cepeda, in which the heavily diminished and demoralized Supreme Directorship would collapse. Tensions would flare up again when the Unitarianist Constitution of 1826 would breakdown after less than two years in effect. This breakdown triggered the Segunda Guerra Desunión (Second Disunity War), and divided the country once again...

GUERRAS DESUNIÒN: (Spanish: Disunity Wars) A series of four civil wars fought in The United Provinces from 1816-1820, 1826-1827, 1828-1831 and 1831-1834. The Guerras Desunión would start shortly after the nation’s independence and divide the United Provinces into bitterly opposed factions. Originally a conflict between Platense political movements, the Unitarianists and the Federalists, the Primera Guerra Desunión (First Disunity War) (1816-1820) was at foremost a low level conflict. Ultimately, Federalist backed League of the Free Peoples (Liga de los Pueblos Libres) ultimately triumphed over the over the Unitarianist Supreme Directorship, during the pivotal battle at Cepeda. For the next eight years an illusion of peace settled in the uneasy United Provinces, but tension flared up after the heavily Unitarianist Constitution of 1826 fell through, pushing the country once again into civil war. The Segunda Guerra Desunión (Second Disunity War) (1826-1827) would lead to the overthrow of then president Bernardino Rivadavia, and the breakdown of central authority in the United Provinces. The Tercera Guerra Desunión (Third Disunity War) (1828-1831) would begin with the deposition of Federalist governor and future President Manuel Dorrego, and end with the with the Treaty of Córdoba. In the Tercera Guerra Desunión, the Unitarianists under Lavelle would briefly occupy Buenos Aires before being defeated by Dorrego and Juan de Rosas at the Battle of Río Federal. The Unitarianist would retreat to west after the loss of Buenos Aires, finding support with sympathetic general José María Paz. Together, they formed the Unitarianist League (Liga Unitaria), to oppose Dorrego and de Rosas...

From The River of Silver: Dorrego, Disunion and the Early United Provinces by James Henry Derringer (1980, Darren University Press, Baltimore, State of Maryland )

...When the dust cleared after the Battle at Río Federal, The Federalist commanders could survey the situation for the first time. The battle had been better than any of Dorrego’s or Rosas’ hopes. The majority of the Unitarianist army now were captured, and although Lavalle was nowhere to be seen, Buenos Aires was within grasp. However, there was a more pressing matter for the commanders: what should be done about the 700 Unitarianist prisoners which had been captured? When the victorious commanders convened on the evening of 20th to discuss the aftermath of their victory, the subject was of prisoners was uneasily avoided. However, a young officer, by a certain Eliazar Díaz, would bring up the subject. The reception of this was clearly documented in Dorrego’s memoirs:

“All the generals, including myself and Rosas, sat in silence, until Estanislao López, meekly suggested we should execute the lot of them. I and quite a few others, including General Mansilla [1], looked at López with a mix horror and shock in our eyes. Then our eyes would drift to Rosas, and he was silently nodding.”

The proposal was vigorously voted down, and was not spoken of by Dorrego again, but it would leave him with a creeping suspicion of the Gaucho governors: especially Rosas. After intense, passionate debate, Dorrego proposed another, radical solution: to integrate the captured units into a new, Federalist professional army. Although Rosas, López, and a few others tried to vote down the proposal, it passed by the narrowest of margins. Rosas, enraged, considered mutinying, but realized that Dorrego had the backing of the prisoners as well as the troops, and did not go through. It was then, Dorrego wrote, that he had a revelation:

“It was at that night after the battle, a day’s march from Rosario, that I realized that the divisions between Federalist and Unitarianist were futile and incomprehensible. The true were the savages who would throw his fellow countryman to the lions if it meant furthering his own political goals. The caudillos were the true enemy. Although I had not fully understood what I had sensed, It would live with me forever.”

The next morning, Dorrego would deliver a speech which would live on in the Platense national consciousness long after Dorrego’s death...

Nearly two decades ago, two hundred and fifty men gathered in Buenos Aires to reject tyranny of and create an independent government, one which serves the people and not the whims of a faraway oppressor. And what do we have now? In the very same cabildo which these men gathered, tyranny, not of a foreign country but of native upbringing rules supreme. Is this what the Lord has set out for this nation? I reject this! The Lord has gifted us with this bountiful land, but we squabble and ruin it. We are all brothers, divided against each other, weak and vulnerable to the likes of Rio de Janeiro. We must all put aside our petty politics, and our squabbles and create a United Provinces truly United...once we mend our divides the United Provinces will achieve her true purpose that the lord has set out for her....

-excerpt of the Río Federal Speech, January 21st, 1829. As recorded by Unitarianist soldier Jose Perón in his Memoirs.

The Río Federal Speech’s significance would not be immediately apparent to that first audience listening from the banks of the Paraná River, whose main concern was whether or not de Rosas’ proposal would carry through. Much to their relief , Dorrego’s more levelheaded idea of a Federalist army was accepted. It would take long after the Guerras Desunión, indeed after Dorrego’s death for the true implications of the speech to be realized. Dorrego’s totally unexpected call for unity, comparable to Bolivarian ideas in faraway Colombia, would characterize the next chapter in the history of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata.

...Dorrego came back the Buenos Aires relieved, finding his wife, Angelita, and his two young daughters unharmed. Nevertheless, Dorrego’s reception in Buenos Aires was tense: The Argentine [2] people were relieved that Lavalle’s fiefdom was,at least temporarily, history, but they were appreciably less thrilled with de Rosas and López being in the city of the Fair Winds [3]. Stories of their brutality, doubtlessly exaggerated but often true, filtered into Buenos Aires, causing the city to brace for possible purges and terror. The purges and terror never materialized, instead, Dorrego called a convention to discuss the proposal for a document which would rule in lieu of a Constitution: the document which would be remembered as the Pacto Nacional (National Pact)....

From El Pacto Nacional: Una Historia by Sancho Allende (1975, La Prensa de la Universidad de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Provincia de Buenos Aires.) (translated from original Spanish)

When Governor Dorrego and his Federalists called the convention to discuss his proposed scheme, it was assumed, not unreasonably, that the convention will get exactly nowhere in creating a balanced constitution. By the end of the first day, February 14th, it seemed like these naysayers were right: Nothing had been agreed on except that convention should meet every week, a proposal by the esteemed diplomat Tomás Guido. The attendance of the convention was disappointing low, only around a third of the invited actually did show up at the San Miguel Fort [4]. Nevertheless, a wide variety of topics were argued: from asking if a temporary constitution was even needed, to vigorous debates about the other, Unitarianist leaning provinces (the Unitarianist League would be created a month later in Mendoza). The infamous caudillos, Estanislao López and Juan de Rosas also attended, but were more of cautious observers than members of the convention . The next day the convention met, the February the 21th, it finally agreed to create a temporary constitution. Again, not much else was agreed, mainly due to dismal attendance. Dorrego and the convention agreed to postpone until more representatives from neighboring provinces could arrive.

The convention convened again a month later, on March 20th. This time, more than four hundred were in attendance, and even some moderate Unitarianists were invited, much to the dismay of hardened Federalists. The convention was again a deadlock, with nothing being agreed, except for a mutual defense clause for all the provinces, which was voted in with a substantial majority. The convention reconvened on the 27th, with yet more people in attendance. It was then that a certain Gregorio Aráoz de Lamadrid, a moderate Unitarianist and friend of Dorrego, who was pardoned at Río Federal, proposed a clause which would create a unified, professional, general army. A “temporary” measure, as he called it. The rather predictable reaction to this proposal was outroar from the caudillos, disdain from the conservatives, and an uncertain silence from the moderates. The proposal was voted down, but it would still linger in the minds of the attending.

Although the focus on the National Pact , it would be an incomplete narrative if Governor Dorrego’s rule in Buenos Aires is ignored. Dorrego immediately began restoring programs and laws which had been neglected or abolished by Lavalle. In his usual populist mindset, universal (male) suffrage was restored, and new elections were called in the House of Representatives. Dorrego’s social programs were also restored. However, these were not Dorrego’s daring and risky move would determine the fate of the Platense nation. Dorrego, whilst the convention still debated Lamadrid’s proposal, began training the Federalist's first professional army with Colonel Ángel Pacheco. The army,funded courtesy of Lavalle’s seized personal funds, comprised of a thousand hardened veterans of the Cisplatine War, and two thousand newly-minted professional soldiers, would decide many of the wars to come.

In the meanwhile, news of the newly minted Unitarianist League had spread alarm in the convention . The next time they met, on the 3rd of April, delegate Juan José Viamonte rose and said: “The longer we sit in our chairs and bicker, the easier General Paz’s [5] job gets...” Viamonte’s sentiments were shared by many of the attending. Nevertheless, in the early hours of the convention , the deadlock persisted and it seemed yet again day of frustration. However, this was shattered by one of the most brilliant political pieces ever written: the Declaration of Rights and Freedoms. Proposed by veteran diplomat José María Roxas y Patrón, it broke the ice for the convention , and marked the true birth of the National Pact ...

From Memoirs by Jose Perón. (originally published in 1865, by Prensa de Fernandez, Mar del Plata,

Provincia de Argentina ) (translated from original spanish)

...I had guard duty on the 3rd. Pacheco told me so on the day before, while we were doing exercises in Almagro, on the outskirts of the city. I did not understand why the Colonel would choose such an inexperienced person for the job, but I was in no position to decline. I woke up early and made my way to the San Miguel Fort along with Cortés and Armendáriz, and a few others. It was a downcast, damp day, with a constant drizzle of rain. In this weather, we trudged along to the gatehouse of the fort, and we made a great show of entering the gates. I took my place inside the Real Audiencia, where they were having the convention.

Inside, It was already crowded with arguing representatives from all over the United Provinces. I remember seeing an exasperated Dorrego, the imposing figure of General Lamadrid, and a few others I recognized. Although my main duty was to guard the convention from any threats, it was impossible not to hear what they were discussing. It started with an air of frustration, and of tension. A tall imposing man, I was later told his name was Viamonte, remarked how much easier Paz’s job now was thanks to the convention . It seemed like the convention, yet again, would achieve nothing. The arguing continued back and forward from the Federalists to the Unitarianists. The rain started to drum heavily on the roof, and the convention getting tenser by the minute.

Then, a short, unassuming delegate stood up. I was unfamiliar with this man, but I was later told his name was José María Roxas y Patrón, the diplomat who forged the hated Treaty of ‘28 [6]. But that is besides the point. Patrón stood up, and began speaking in a firm but controlled tone. Previous arguments were hushed up.

“Gentlemen, although we all have our differences in ideology and doctrine, I take it that we all agree in building a nation on freedom and a rejection of tyranny… We do not squabble on that regard. We all supported the May Revolution, and those ideals of justice and freedom. We must remember why we are drawing up this constitution...to guarantee not only the stability and a union of provinces, but a union of free peoples with certain fundamental rights...It is something which we too often neglect. Our temporary constitution, in a time of war, must protect against the excess of Lavalle, of others....I propose a Charter of Freedoms to the convention.”

Before he could finish, one of the delegates, I think Caudillo López, called out for him to show this so called “Charter of Freedoms.” Patrón obliged, pulling out a folded piece of paper and handed it to López, asking him to read it…. It seemed like an eternity, but when he was finished, a flurry of questions and demands roared across the room. One person demanded to know if the charter would accommodate the Catholic religion. Another demanded for freedom of worship. Patrón , with the kind of brilliant speaking I had never heard before… the one which won over the delegates on that April day. Somehow, he deflected all these questions from all the delegates, liberal and conservative, populist to aristocratic. What Patrón created was the great compromise: a binding force which would unite the Disunited Provinces…

From El Pacto Nacional: Una Historia by Sancho Allende (1975, La Prensa de la Universidad de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Provincia de Buenos Aires.) (translated from original Spanish)

Patrón with a historic mastery of compromise, sold a document which would not fall flat like so many others in history. In an unheard of moment of unity , both Unitarians and Federalists created the document during secret meetings, as well as significant input from Governor Dorrego. Patrón had done the impossible: he had created a document which nearly everyone felt inclined to agree with. The religion issue was played away by making Catholicism the official religion of state, and at the same time prohibiting abuse and intolerance based on the fact. It guaranteed the right to vote for all adult males, but even the conservatives felt obligated to vote for it, as Patrón had implicated that it was in line with a rejection of Spanish tyranny: everyone agreed with that. The right to a fair trial was laid out, as well as freedom of press. Everyone had the same rights, and asylum of criminals was forbidden. It did not guarantee the right to form militia, but it did guarantee the right to arms. The guarantee of a republican federal government was laid out. Patrón did not specify the customs tax, that issue was made ambiguous. However, tariffs between provinces was prohibited. A gradualist abolition of slavery laid out, with slavery to be abolished by 1835.

By a surprising vote, the Charter of Freedoms passed, mainly due to brilliant rhetoric from Patrón. The caudillos initially rejected, but in fear of being seen tyrants, and the promise of being temporary, eventually accepted it. The Conservatives accepted because of its prohibition of inter-provincial tariffs, and Catholic leanings. The Liberals accepted it because of it’s unofficial freedom of religion and press. The Charter affirmed , for the first time in Platense history, rights which were regularly ignored and broken during the Wars of Independence and the Wars of Disunion. The Charters of Freedom joined a prestigious list of documents which would shape and change the way we look at government: The Laws of Hammurabi, the Twelve Tables, The Magna Carta, the American Bill of Rights and the Declaration of the Rights of Man. The Charter of Freedoms was the product of a careful compromise as well as the sum of all the aforementioned documents. The Charter of Freedoms would outlive everyone there to vote on it, and in some ways would outlive the very constitution it was created for…

[1] Lucio Norberto Mansilla, Federalist governor of Entre Rios OTL.

[2] Refers to people living around the Rio de la Plata region.

[3] Buenos Aires’ translation, from Spanish.

[4] OTL Casa Rosa. The San Miguel Fort, which used to sit where Casa Rosa sits now, was never demolished TTL.

[5] Brigadier General José María Paz, OTL and TTL leader of the Unitarianist League.

[6] Treaty of Montevideo OTL.

Last edited:

Chapter 3: The War in the Interior

The United Provinces are a single triumph in a continent of tragedies. They are the only country I commend in the whole mess formerly called Spanish America.

-John L. O'Sullivan, The New York Morning News, July 1850.

"... the bravest military operation of which I have been a witness or actor in my long career... I have battled with more hardened, more disciplined, more educated, but braver troops, never."

-José María Paz, remarking about Quiroga’s troops during the Battle of La Tablada, 1829. OTL.

From Lander’s World Cyclopedia, 4th Edition. (1978, Durrington Press, Hartford, Connecticut.)

UNITARIANISM (Platense political movement): A political movement and party active in the United Provinces from 1816 to 1836. Unitarianism, which advocated for a centrally organized government with little state autonomy, was founded shortly after the declaration of independence in 1816 from Spain. Although Unitarianism was first proposed as a way to unite the United Provinces, Unitarianist principals heavily favor Buenos Aires, and other provinces were often ignored. This led to the outlying, or gaucho provinces forming an opposing faction, the Federalists. This rift would start the Guerras Desunión (Disunity Wars). The Unitarianist would be defeated at Cepada in 1820, during the Primera Guerra Desunión (First Disunity War), but unresolved tensions would culminate to the disastrous Unitarianist Constitution of 1826, which caused the Federalist provinces rise in revolt....

...The Unitarianist officer José María Paz would be placed in command of the army of the Liga Unitaria, and go on to win a string of impressive victories, resulting in the Liga Unitaria’s control of Córdoba and and the death of several Federalist warlords, or caudillos...

From The River of Silver: Dorrego, Disunion and the Early United Provinces by James Henry Derringer (1980, Darren University Press, Baltimore, State of Maryland )

It was clear, warm day in Mendoza, on March the 20th of 1829, representatives of the interior provinces met to discuss the alarming events coming from Buenos Aires. A disheveled Lavalle, having escaped the battlefield at Río Federal, told a doubtlessly exaggerated tale of the battle and the populist “demagogue” Dorrego. The provincial representatives may disagree with Lavalle’s aristocratic tendencies and paranoia, but were distressed at the thought of Rosas and his half-savage gauchos terrorizing Buenos Aires. Therefore, the provincial representatives that day, almost unanimously signed a declaration of unity against Federalist aggression .The alliance, taking the name Liga Unitaria (Unitarianist League) gave General José María Paz, the post of supreme commander of Unitarian forces [1].

José María Paz, a talented commander and veteran of the War of Independence, was reluctant to fight his own countrymen. Nevertheless, he accepted the post. Paz was given command of over 1,200 professional soldiers and what was left of Lavalle’s contingent, and quickly marched to Córdoba. When arriving, Paz met his former comrade Juan Bautista Bustos, now Federalist governor of Córdoba. Paz demanded Bustos to elect a new governor since his two terms had expired. Nevertheless, it was obvious to everyone that Paz intended to be that new governor. Bustos, offered to run an election, but he and Paz would be prohibited from participating. Paz was sure that Bustos was just biding his time for reinforcements, and clashed at Alta Gracia, on the 23rd of April.

Bustos, an excellent statesman but never a very good commander, unwisely chose to position his troops on the low ground, near the town. Sensing weakness, Paz quietly positioned his artillery on the hills surrounding the town. When daybreak arrived, Bustos’ forces were torn apart by Paz’s superior artillery, and finished off by Paz’s professional troops. Bustos and his remaining force( around 1,000) deciding that further resistance is unwise, retreated to Rosario. Thankfully for the Federalists , Bustos did not suffer from morale problems, and he speedly arrived on June the 4th. There sent messengers to Buenos Aires warning them of the Unitarianist threat.

In Buenos Aires, Dorrego’s administration was surprisingly smooth. His quiet redirection of customs taxes into the military went unnoticed, and the weather was mild, allowing for more exportation of grain and beef. However, the convention is a rather different story. After the surprise passage of the Carta de las Libertades (Charter of Freedoms) The bickering representatives slid once again into a deadlock. Juan de Rosas and Estanislao López returned back to their gaucho provinces, much to the relief of Dorrego, but a deadlock persisted. Dorrego was getting increasingly impatient and frustrated at the convention, but action was fast approaching…

When Bustos’ messengers arrived at Buenos Aires on the 10th, they provoked a new flurry of panic from the convention, which was scheduled to meet again on the 12th. In the panicked, confused meeting, the convention hastily approved Lamadrid’s General Army proposal from march, and quickly authorized Dorrego and Coronel Pacheco to create it. This was a small relief for the increasingly frustrated Dorrego, as he wrote in his diary: “Thank the Lord for Paz, he has allowed us to win the war!” The army was procured suspiciously fast, mainly because Dorrego had secretly created it months before. That very next week, The convention promoted Ángel Pacheco to general, placing him in command of the newborn Ejército del Pacto Nacional (Army of the National Pact ). The Ejército del Pacto Nacional, numbering 2,500, was a well-disciplined, professional force. Funded by private donations, the army was a formidable weapon: one that would be put to good use…

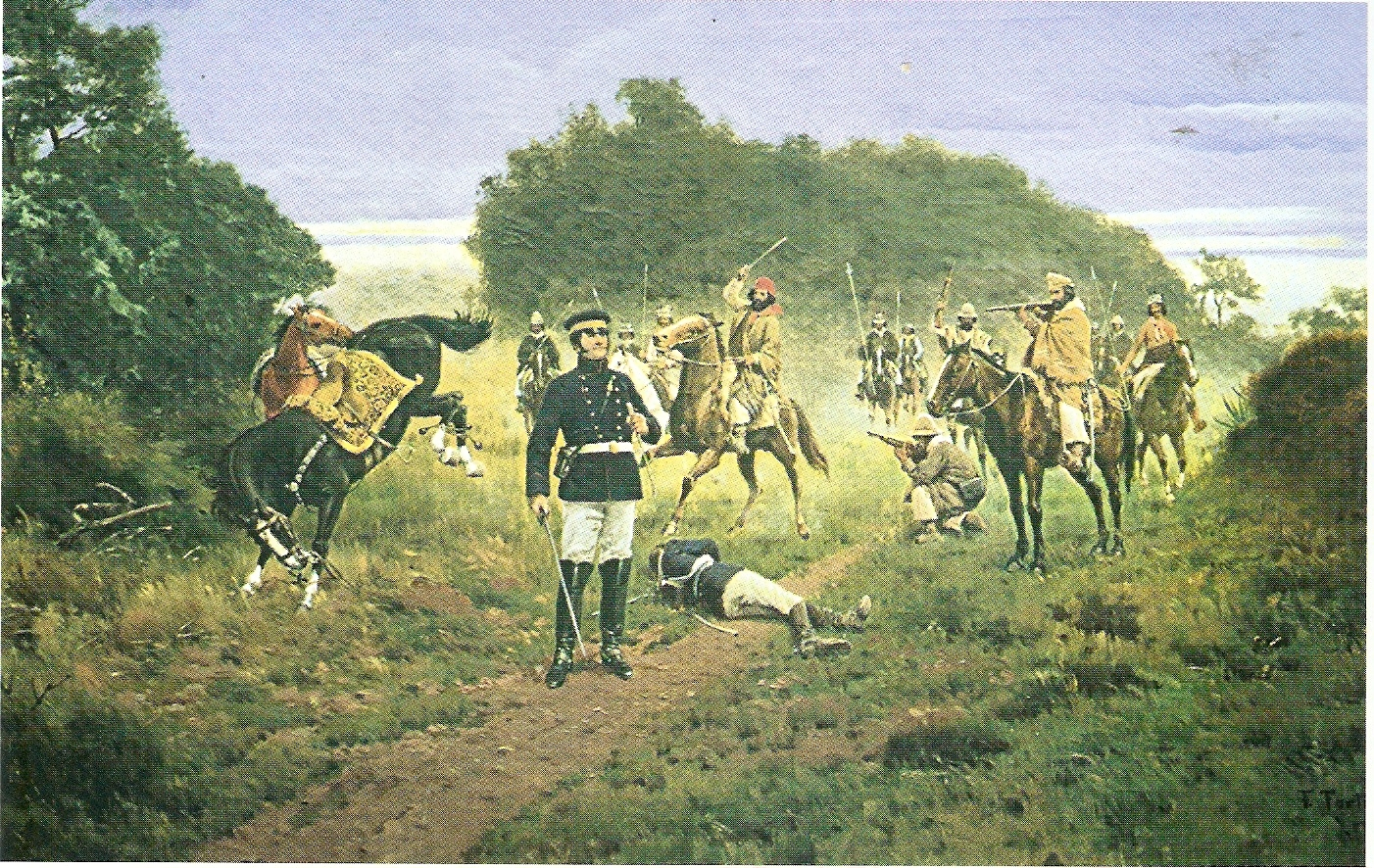

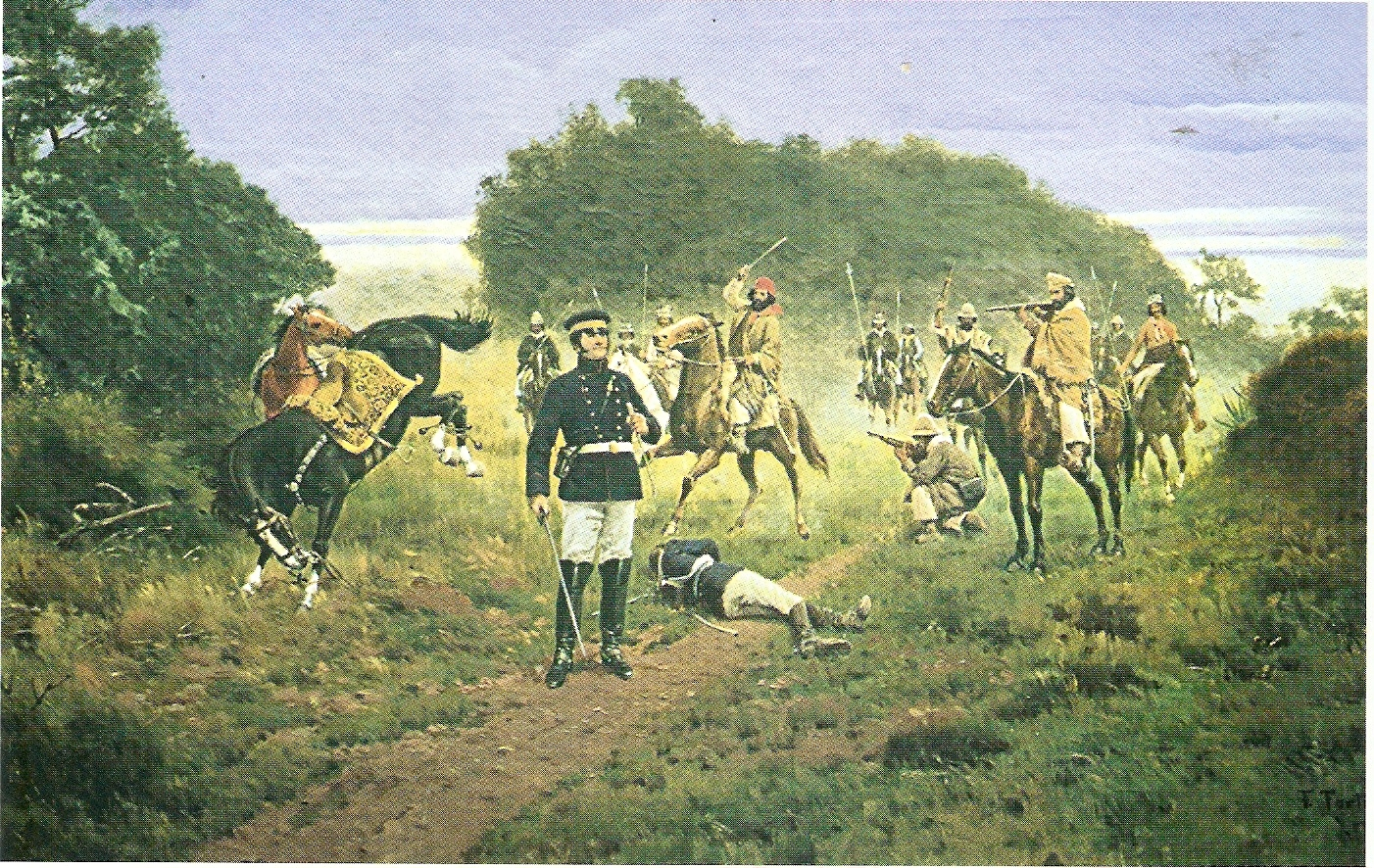

Meanwhile, newly created Governor of Córdoba, José María Paz, struggles to govern an unruly province. Juan Bautista Bustos was a competent and popular governor, guaranteeing many of his citizens fundamental rights and abiding the rule of law. Hence,the people did not think highly of Paz for suddenly overthrowing Bustos . José María Paz attempted to calm the populace by keeping most of Bustos’ policies, but, unfortunately for Paz, timely intervention from caudillo Juan Facundo Quiroga prevented Paz from going further. Quiroga, the infamously cruel and bloodthirsty caudillo from La Rioja, had come with an equally savage army of 5,000. Made up of seasoned gaucho calvary, Quiroga and his forces posed a major challenge to even a seasoned general such as Paz. Quiroga‘s forces arrived on the border of the Córdoba province on the 15th. Razing and looting towns along the way, Quiroga swooped down from La Rioja, around the Sierras de Córdoba, and pushed up from the south. Although Paz was facing internal revolt back in Córdoba, Paz was forced to counter Quiroga ‘s threat by marching his troops south. Quiroga and Paz would clash again on the hills near the modern Villa del Serrano [2], in the Battle of Las Crestas. Paz had positioned his outnumbered army on a low, unnamed ridge, but left a large, obvious gap in his line, near his center. Paz then waited for Quiroga.

Quiroga did indeed come, and did notice the glaring gap in Paz’s line. Fearing it might close, Quiroga, in the early hours of the 22nd of June, committed of his 4,500 gaucho riders, 2,000 in rushing into the gap and decisively breaking the Unitarianists. Paz’s artillery pieces, raining down on Quiroga's men, encouraged the gaucho to act quickly. Quiroga personally led the charge, and at first the attack seemed to be successful: Quiroga’s men breached the line but then realized Paz’s strategy . Paz, a learned man familiar with Bonapartian [3] tactics, had his men had form squares, and started picking off the gaucho cavalry. In particular, they were told to aim for a man with impressive side whiskers and with a general’s uniform.

Whether or not Juan Facundo Quiroga realized of the trap, he did not withdraw. Instead, he ordered his lieutenant, Benito Villafañe, to try to break up the squares with artillery fire. When asked if he were to flee, Quiroga replied with a gruff “ I will fight until I can fight no more.” Quiroga then joined back into the fray. Thirty minutes later, Juan Facundo Quiroga would be brought down by a lucky bullet. The bullet punctured his skull, killing the caudillo instantly. The minutes after, the gauchos, after suffering heavy casualties, panicked and ran. Quiroga and many of his lieutenants were dead, and his army was in a full retreat north. Córdoba was firmly in Unitarianists hands. The news of Quiroga’s devesting defeat sent waves throughout the convention assembled Buenos Aires. The convention met on the day the news was delivered, and was thrown into yet another panic. In contrast, Manuel Dorrego’s spirits were lightened: Dorrego had grown the secretly despise the caudillos, and sympathized with Paz. Certainly, Dorrego hoped that Paz would be able to reconcile with the convention. Dorrego would later write:“I regard Paz far more highly than the likes of Juan Facundo Quiroga. He is a honorable commander and governor.”

In truth, Paz’s victory was a blessing for the still-unofficial Dorrego faction in the convention. Dorrego allies, such as Juan José Viamonte and Lucio Norberto Mansilla, pushed for the finalization of the Pacto Nacional (National Pact ), which was finally nearing completion. The normally reluctant convention, with the growing defeats in the interior,began to realize the need for a united front against the Unitarianists. Therefore, the convention hosted tense meetings in the beginning of August to decide whether or not to ratify. Finally, on the 14th, by a historic vote, the pact was ratified. The completed pact, a heavily Dorrego-influenced document, it created a “temporary” union of provinces, with a joint leadership elected by the provincial legislatures. The Charter of Freedoms was enshrined in the pact, as well as provisions for naturalization and free trade. A centrally organized army was mandated, and a “temporary” Asamblea Federal (Federal Assembly) was created. The only small issue now was that the Pacto Nacional had to be ratified by the provincial legislatures...

The first legislature to vote on the pact was the Buenos Aires House of Representatives. The House, elected that June, had a comfortable majority of pro-Dorrego representatives, and the Pacto Nacional was ratified without much of a mumble of opposition. In Corrientes, the governor, Pedro Ferré, who had much desired national unity, convinced the province to ratify as the only way to ensure a united Platense nation-state. Corrientes was therefore the second province to ratify on 28th. The gaucho provinces, composed of Estanislao López’s Santa Fe and Rosas’ Entre Rios (Rosas was elected to the governorship in early May), were more reluctant to ratify. After much consideration, they ratified in September, on the 15th. Juan Felipe Ibarra’s Santiago del Estero province ratified on the 17th. In the interior, La Rioja was thrown into chaos by the death of the caudillo Quiroga .His lieutenant Benito Villafañe, quickly took control of the province and proclaimed himself governor of the province, and fortified for any possible Unitarianist incursions. His province refused to ratify. However, a certain officer named Jose Felix Aldao, who had escaped Las Crestas, reasserted himself governor of San Luis, and ratified the pact on the 23rd, with San Juan ratifying on the 25th.

It was decided that the sufficient amount of provinces had ratified, and the Pacto Nacional formally went into force on the 1st of October. The country would be led by the Asamblea Federal and the joint leadership ,later retrospectively labelled the Ùltima Junta (Last Junta). The Ùltima Junta , composed of Gregorio Aráoz de Lamadrid, Juan José Viamonte and Tomás Guido, was a careful balance struck up by Dorrego and the provincial legislatures.The Ùltima Junta was comprised of relatively non-controversial military leaders and diplomats, which would be a uniting force for the mixed group of Unitarianists and Federalists calling themselves the Pacto Nacional. Meanwhile, the Ejército del Pacto Nacional continued to train on the outskirts of Buenos Aires, building morale and strength for future campaigns. What was left of Juan Bautista Bustos’ forces also joined them, bringing the total number of the Ejército del Pacto Nacional to 4,500.

José María Paz’s rule in Córdoba had stabilized by November, after several rocky months. Paz, in December of 1829, set out on a military expedition with 4,000 troops to quell the Federalist strongholds of La Rioja, San Juan, and San Luis. Paz headed south from Córdoba, reaching the border of the Federalist-controlled San Luis province on Christmas day. The governor, Jose Felix Aldao, attempted a desperate defence on January the 2nd of 1830. Aldao, outnumbered and outgunned, was beaten back without much of a fight, and captured. Paz rode triumphantly into San Luis triumphantly on the 10th. Unfortunately, the day was blisteringly hot, and Paz, in a stuffy military uniform, would suffer a heat stroke...Although he survived, it would incapacitate him for several precious weeks, allowing word to reach Buenos Aires that Córdoba was vulnerable and undefended…

[1] As in OTL, Paz is the commander of the Liga Unitaria, but they form slightly earlier and in a different city.

[2] OTL Los Cóndores, Córdoba.

[3] OTL Napoleonic.

The United Provinces are a single triumph in a continent of tragedies. They are the only country I commend in the whole mess formerly called Spanish America.

-John L. O'Sullivan, The New York Morning News, July 1850.

"... the bravest military operation of which I have been a witness or actor in my long career... I have battled with more hardened, more disciplined, more educated, but braver troops, never."

-José María Paz, remarking about Quiroga’s troops during the Battle of La Tablada, 1829. OTL.

From Lander’s World Cyclopedia, 4th Edition. (1978, Durrington Press, Hartford, Connecticut.)

UNITARIANISM (Platense political movement): A political movement and party active in the United Provinces from 1816 to 1836. Unitarianism, which advocated for a centrally organized government with little state autonomy, was founded shortly after the declaration of independence in 1816 from Spain. Although Unitarianism was first proposed as a way to unite the United Provinces, Unitarianist principals heavily favor Buenos Aires, and other provinces were often ignored. This led to the outlying, or gaucho provinces forming an opposing faction, the Federalists. This rift would start the Guerras Desunión (Disunity Wars). The Unitarianist would be defeated at Cepada in 1820, during the Primera Guerra Desunión (First Disunity War), but unresolved tensions would culminate to the disastrous Unitarianist Constitution of 1826, which caused the Federalist provinces rise in revolt....

...The Unitarianist officer José María Paz would be placed in command of the army of the Liga Unitaria, and go on to win a string of impressive victories, resulting in the Liga Unitaria’s control of Córdoba and and the death of several Federalist warlords, or caudillos...

From The River of Silver: Dorrego, Disunion and the Early United Provinces by James Henry Derringer (1980, Darren University Press, Baltimore, State of Maryland )

It was clear, warm day in Mendoza, on March the 20th of 1829, representatives of the interior provinces met to discuss the alarming events coming from Buenos Aires. A disheveled Lavalle, having escaped the battlefield at Río Federal, told a doubtlessly exaggerated tale of the battle and the populist “demagogue” Dorrego. The provincial representatives may disagree with Lavalle’s aristocratic tendencies and paranoia, but were distressed at the thought of Rosas and his half-savage gauchos terrorizing Buenos Aires. Therefore, the provincial representatives that day, almost unanimously signed a declaration of unity against Federalist aggression .The alliance, taking the name Liga Unitaria (Unitarianist League) gave General José María Paz, the post of supreme commander of Unitarian forces [1].

José María Paz, a talented commander and veteran of the War of Independence, was reluctant to fight his own countrymen. Nevertheless, he accepted the post. Paz was given command of over 1,200 professional soldiers and what was left of Lavalle’s contingent, and quickly marched to Córdoba. When arriving, Paz met his former comrade Juan Bautista Bustos, now Federalist governor of Córdoba. Paz demanded Bustos to elect a new governor since his two terms had expired. Nevertheless, it was obvious to everyone that Paz intended to be that new governor. Bustos, offered to run an election, but he and Paz would be prohibited from participating. Paz was sure that Bustos was just biding his time for reinforcements, and clashed at Alta Gracia, on the 23rd of April.

Bustos, an excellent statesman but never a very good commander, unwisely chose to position his troops on the low ground, near the town. Sensing weakness, Paz quietly positioned his artillery on the hills surrounding the town. When daybreak arrived, Bustos’ forces were torn apart by Paz’s superior artillery, and finished off by Paz’s professional troops. Bustos and his remaining force( around 1,000) deciding that further resistance is unwise, retreated to Rosario. Thankfully for the Federalists , Bustos did not suffer from morale problems, and he speedly arrived on June the 4th. There sent messengers to Buenos Aires warning them of the Unitarianist threat.

In Buenos Aires, Dorrego’s administration was surprisingly smooth. His quiet redirection of customs taxes into the military went unnoticed, and the weather was mild, allowing for more exportation of grain and beef. However, the convention is a rather different story. After the surprise passage of the Carta de las Libertades (Charter of Freedoms) The bickering representatives slid once again into a deadlock. Juan de Rosas and Estanislao López returned back to their gaucho provinces, much to the relief of Dorrego, but a deadlock persisted. Dorrego was getting increasingly impatient and frustrated at the convention, but action was fast approaching…

When Bustos’ messengers arrived at Buenos Aires on the 10th, they provoked a new flurry of panic from the convention, which was scheduled to meet again on the 12th. In the panicked, confused meeting, the convention hastily approved Lamadrid’s General Army proposal from march, and quickly authorized Dorrego and Coronel Pacheco to create it. This was a small relief for the increasingly frustrated Dorrego, as he wrote in his diary: “Thank the Lord for Paz, he has allowed us to win the war!” The army was procured suspiciously fast, mainly because Dorrego had secretly created it months before. That very next week, The convention promoted Ángel Pacheco to general, placing him in command of the newborn Ejército del Pacto Nacional (Army of the National Pact ). The Ejército del Pacto Nacional, numbering 2,500, was a well-disciplined, professional force. Funded by private donations, the army was a formidable weapon: one that would be put to good use…

Meanwhile, newly created Governor of Córdoba, José María Paz, struggles to govern an unruly province. Juan Bautista Bustos was a competent and popular governor, guaranteeing many of his citizens fundamental rights and abiding the rule of law. Hence,the people did not think highly of Paz for suddenly overthrowing Bustos . José María Paz attempted to calm the populace by keeping most of Bustos’ policies, but, unfortunately for Paz, timely intervention from caudillo Juan Facundo Quiroga prevented Paz from going further. Quiroga, the infamously cruel and bloodthirsty caudillo from La Rioja, had come with an equally savage army of 5,000. Made up of seasoned gaucho calvary, Quiroga and his forces posed a major challenge to even a seasoned general such as Paz. Quiroga‘s forces arrived on the border of the Córdoba province on the 15th. Razing and looting towns along the way, Quiroga swooped down from La Rioja, around the Sierras de Córdoba, and pushed up from the south. Although Paz was facing internal revolt back in Córdoba, Paz was forced to counter Quiroga ‘s threat by marching his troops south. Quiroga and Paz would clash again on the hills near the modern Villa del Serrano [2], in the Battle of Las Crestas. Paz had positioned his outnumbered army on a low, unnamed ridge, but left a large, obvious gap in his line, near his center. Paz then waited for Quiroga.

Quiroga did indeed come, and did notice the glaring gap in Paz’s line. Fearing it might close, Quiroga, in the early hours of the 22nd of June, committed of his 4,500 gaucho riders, 2,000 in rushing into the gap and decisively breaking the Unitarianists. Paz’s artillery pieces, raining down on Quiroga's men, encouraged the gaucho to act quickly. Quiroga personally led the charge, and at first the attack seemed to be successful: Quiroga’s men breached the line but then realized Paz’s strategy . Paz, a learned man familiar with Bonapartian [3] tactics, had his men had form squares, and started picking off the gaucho cavalry. In particular, they were told to aim for a man with impressive side whiskers and with a general’s uniform.

Whether or not Juan Facundo Quiroga realized of the trap, he did not withdraw. Instead, he ordered his lieutenant, Benito Villafañe, to try to break up the squares with artillery fire. When asked if he were to flee, Quiroga replied with a gruff “ I will fight until I can fight no more.” Quiroga then joined back into the fray. Thirty minutes later, Juan Facundo Quiroga would be brought down by a lucky bullet. The bullet punctured his skull, killing the caudillo instantly. The minutes after, the gauchos, after suffering heavy casualties, panicked and ran. Quiroga and many of his lieutenants were dead, and his army was in a full retreat north. Córdoba was firmly in Unitarianists hands. The news of Quiroga’s devesting defeat sent waves throughout the convention assembled Buenos Aires. The convention met on the day the news was delivered, and was thrown into yet another panic. In contrast, Manuel Dorrego’s spirits were lightened: Dorrego had grown the secretly despise the caudillos, and sympathized with Paz. Certainly, Dorrego hoped that Paz would be able to reconcile with the convention. Dorrego would later write:“I regard Paz far more highly than the likes of Juan Facundo Quiroga. He is a honorable commander and governor.”

In truth, Paz’s victory was a blessing for the still-unofficial Dorrego faction in the convention. Dorrego allies, such as Juan José Viamonte and Lucio Norberto Mansilla, pushed for the finalization of the Pacto Nacional (National Pact ), which was finally nearing completion. The normally reluctant convention, with the growing defeats in the interior,began to realize the need for a united front against the Unitarianists. Therefore, the convention hosted tense meetings in the beginning of August to decide whether or not to ratify. Finally, on the 14th, by a historic vote, the pact was ratified. The completed pact, a heavily Dorrego-influenced document, it created a “temporary” union of provinces, with a joint leadership elected by the provincial legislatures. The Charter of Freedoms was enshrined in the pact, as well as provisions for naturalization and free trade. A centrally organized army was mandated, and a “temporary” Asamblea Federal (Federal Assembly) was created. The only small issue now was that the Pacto Nacional had to be ratified by the provincial legislatures...

The first legislature to vote on the pact was the Buenos Aires House of Representatives. The House, elected that June, had a comfortable majority of pro-Dorrego representatives, and the Pacto Nacional was ratified without much of a mumble of opposition. In Corrientes, the governor, Pedro Ferré, who had much desired national unity, convinced the province to ratify as the only way to ensure a united Platense nation-state. Corrientes was therefore the second province to ratify on 28th. The gaucho provinces, composed of Estanislao López’s Santa Fe and Rosas’ Entre Rios (Rosas was elected to the governorship in early May), were more reluctant to ratify. After much consideration, they ratified in September, on the 15th. Juan Felipe Ibarra’s Santiago del Estero province ratified on the 17th. In the interior, La Rioja was thrown into chaos by the death of the caudillo Quiroga .His lieutenant Benito Villafañe, quickly took control of the province and proclaimed himself governor of the province, and fortified for any possible Unitarianist incursions. His province refused to ratify. However, a certain officer named Jose Felix Aldao, who had escaped Las Crestas, reasserted himself governor of San Luis, and ratified the pact on the 23rd, with San Juan ratifying on the 25th.

It was decided that the sufficient amount of provinces had ratified, and the Pacto Nacional formally went into force on the 1st of October. The country would be led by the Asamblea Federal and the joint leadership ,later retrospectively labelled the Ùltima Junta (Last Junta). The Ùltima Junta , composed of Gregorio Aráoz de Lamadrid, Juan José Viamonte and Tomás Guido, was a careful balance struck up by Dorrego and the provincial legislatures.The Ùltima Junta was comprised of relatively non-controversial military leaders and diplomats, which would be a uniting force for the mixed group of Unitarianists and Federalists calling themselves the Pacto Nacional. Meanwhile, the Ejército del Pacto Nacional continued to train on the outskirts of Buenos Aires, building morale and strength for future campaigns. What was left of Juan Bautista Bustos’ forces also joined them, bringing the total number of the Ejército del Pacto Nacional to 4,500.

José María Paz’s rule in Córdoba had stabilized by November, after several rocky months. Paz, in December of 1829, set out on a military expedition with 4,000 troops to quell the Federalist strongholds of La Rioja, San Juan, and San Luis. Paz headed south from Córdoba, reaching the border of the Federalist-controlled San Luis province on Christmas day. The governor, Jose Felix Aldao, attempted a desperate defence on January the 2nd of 1830. Aldao, outnumbered and outgunned, was beaten back without much of a fight, and captured. Paz rode triumphantly into San Luis triumphantly on the 10th. Unfortunately, the day was blisteringly hot, and Paz, in a stuffy military uniform, would suffer a heat stroke...Although he survived, it would incapacitate him for several precious weeks, allowing word to reach Buenos Aires that Córdoba was vulnerable and undefended…

[1] As in OTL, Paz is the commander of the Liga Unitaria, but they form slightly earlier and in a different city.

[2] OTL Los Cóndores, Córdoba.

[3] OTL Napoleonic.

Last edited:

Chapter 4: A Final Hurrah

From Memoirs by Jose Perón. (originally published in 1865, by Prensa de Fernandez, Mar del Plata,

Provincia de Argentina ) (translated from original spanish)

...We reached the border of the Córdoba province, or at least near it, on the 3rd of February. The terrain was getting increasingly monotonous as we passed more of the uninhabited pampas, with scattered villages throughout. The busy docks of Buenos Aires seemed like a century away from these untamed grasslands. For long stretches of time, we saw no mark of the human civilization, other than the dusty road we marched on. We occasionally saw a Nandu [1] and herds of deer, which further reinforced this out of the time feeling. All around were seas of grass, stretching to what seemeded like the ends of the earth. Although striking for the first few days, it soon devolved into something of a boring slog. As a remedy to our boredom, Armendáriz and I named the stars late during the nights. We talked for the first few nights, but eventually fell into silent contemplation.It is remarkable, for a person of the city like I, what wonders quiet can do.

Inevitably, the boredom did creep in. In the long evenings, I thought about my future. What shall I do after these wars? Join the navy? Find myself a wife? I stopped thinking about my future on the the 2nd March, after weeks of marching in the pampas, I first sighted the magnificent peaks of the Sierra de Córdoba. A fearsome sight, especially for one who had been in the plains for the last two years. Alas, I was distracted by our arrival into Córdoba. It was rumoured that a force had been left behind by Paz to protect Córdoba, while he was out campaigning. I later learned that Paz intended his campaign to be a temporary affair, and to be back in Córdoba in time to defend against any Federalist incursions by the National Pact. Nevertheless, we set off before daybreak towards Córdoba, unsure of how many of Paz’s ,em we would encounter…

...Finally, we reached the city of Córdoba. Córdoba was a stark contrast to the trade city of Buenos Aires. It did have a few similarities with Buenos Aires : it is undoubtedly a city, home to 11,000 souls, it is the largest in the entire interior . Like Buenos Aires, it was built on a river. This is where the similarities end. The “river” barely qualifies to be a stream, let alone it’s “first river” designation. The sea is more than two hundred leagues away. Very few foreign merchants come to this city in the middle of the country: incredibly, poverty is even more widespread than in Buenos Aires: an impressive, if somewhat dubious feat.

...As fate decided, Paz had apparently been struck sick, and only a cursory force led by General López remained in Córdoba to defend against “Pacheco’s Devils”, as they were now calling us. At first, I assumed they had deserted the city: the streets were deathly quiet. We congregated at the Plaza Central,and discussed what to do next. As we discussed our plans, the unmistakable sound of gunfire ringed from one of the back alleys. We rushed over there, and we were met with a dozen bloodied soldiers, and few bodies, and what appeared to be a very high ranking officer ...

From The River of Silver: Dorrego, Disunion and the Early United Provinces by James Henry Derringer (1980, Darren University Press, Baltimore, State of Maryland )