You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Wrapped in Flames: The Great American War and Beyond

- Thread starter EnglishCanuck

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 157 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

The New World Order 1866 Part 4: The Mexican Empire Chapter 126: The Balance of Power in North America Chapter 127: What If? Chapter 128: 1866 A Year in Review Chapter 129: Grasping at Thrones Chapter 130: Plots in Motion Chapter 131: Trans-Atlantic Troubles Chapter 132: A Want of Preparation

Chapter 3: Legalities

Chapter 3: Legalities

Quebec City, December 1861

The carriage rumbled down the cobbled streets of Canada’s oldest city and away from the assembly hall towards the boarding homes which housed two of the most influential men in the Province of Canada. The horses’ breath caused steam to rise as though from a locomotive, and the drivers own breathing merely added to the light mist which headed out in front of the carriage. Its two occupants were bundled up securely inside, more comfortable than the driver, but not much warmer than they would have been outside.

George Cartier, Deputy Premier of the Province of Canada, sat across from his counterpart, John A. Macdonald, Primer of the Province of Canada. There was a marked contrast between the two. Cartier was dressed as all respectable members of the Montreal elite would be, emulating the latest British fashions in a double breasted frock coat with respectable trousers and a silk hat. His appearance was impeccable with well-groomed hair and a cleanly shaven face.

Macdonald, by contrast, wore a deep blue coat with an outrageously red cravat and wide checkered trousers, all calculated to bring attention to himself. He could hardly fail to gain attention with his poorly kept curly hair sticking out at odd angles from under his hat, his cheeks in need of a simple shave (though he never let it grow into a full beard) and his enormous nose which seemed to take up the better part of his face. While Cartier tried to maintain a dignified bearing Macdonald lounged as though he were at a taproom.

They were on their way home from an acrimonious debate amongst the Assembly regarding the crisis which had developed south of the border. However, they had also been forced to discuss a recent complication in the relationship between the two nations. Macdonald was fuming.

“Damn that wretched prig of a police magistrate!” he swore angrily. “By what authority did he presume to release all of those bandits?”

Cartier frowned. The ‘wretched prig’ he referred to was Charles-Joseph Coursol, one of Montreal’s leading judges. He had been despatched to preside over the trial of the group of Confederate raiders captured in October in the aftermath of the Border Crisis. The trial had been long, and Coursol had, rather than consulting with his superior the Attorney General of Canada East or even with other legal notes, had handed down a verdict which released the raiders. He had defended his action by claiming that he had no jurisdiction to sentence and extradite the prisoners as the British had not proclaimed the Canadian Extradition Act of 1861. Cartier understood Macdonald’s fury.

“That he did not bother to check with his superiors is a travesty. The law may have been unclear, but that does not excuse his actions.” Cartier said.

“The precedent is clear. They could have been easily turned over to the Northern authorities under the articles of the Webster-Ashburton Treaty and that would be the end of it! I’m entirely satisfied with the decision to remove him from the bar.” Macdonald grumbled.

“It may displease some powerful people in Montreal.” Cartier cautioned.

“He can serve his penance in the militia. There he has a fine social position and can posture to his heart’s desire.”

“On that matter,” Cartier interjected “how do you feel the militia debates have gone in the Assembly?” Macdonald leaned forward in the carriage and furrowed his brow.

“It seems as though we can rely on our Conservative members easily. I do have concerns about your Bleus however.”

“They can be kept on side, provided the crisis continues. The mutual fear of invasion all English and French share is a powerful motivator. Should things calm down, we may be hard pressed to pass any legislation regarding the militia in the province. However, I do believe that no matter what comes they will vote as they always have.” Cartier replied.

“Reassuring, but we still have a problem from the Clear Grits. I don’t know how John S. will react to the debates He’s been quiet so far.” Cartier nodded knowingly. The leader of the Clear Grit faction in Canada West, John Sandfield Macdonald was the current head of the opposition in government. He had taken over from George Brown after his government had collapsed in the infamous Double Shuffle of 1858. John S’s party controlled a powerful swing vote, which in accordance with the other faction of radicals in the Assembly, the Rouges under Dorion, could easily upset any decision the alliance between Cartier’s Bleus and Macdonald’s Conservatives came to.

“Thus far John. S seems to be more concerned over cost rather than the bill itself. If the crisis continues, I think he can be persuaded to keep his Grits on side.” Macdonald said sagely.

“I sincerely doubt Dorion can be persuaded to side with any legislation which even smells like military action.” Cartier said.

“Bah, what does Dorion ever do but complain? He doesn’t even hold a cabinet position, while I now hold the dubious honor of being the only triple minister in the Province! I’m still the Premier and Attorney General, and now I’ve stepped into the post of Minister of Militia to try and bring some consensus in the Assembly on the matter of defence!”

“What about Dorion’s accusation that your creation of the Minister of Militia position is all an excuse to stomp around the Assembly dressed up in a red coat and gold braid?” Cartier asked. Macdonald snorted.

“I could hardly manage the dignity of one of the Queen’s officers. Can you imagine that? Me in a uniform? It would be like a sow in a ball gown!” He and Cartier both burst into laughter at the ludicrous mental image. Macdonald took a more serious tone soon afterward.

“Irregardless of the insane accusations of a few radicals, we still have an uphill battle in the Assembly over militia spending. However, some spending will have to be done whether the Assembly wants to or not. Already we have volunteers drilling from Chateuguay to Windsor. London wants us to take on more of the burden for defence.”

“It hardly seems just for the government in London to demand us to burden ourselves with the cost of defence when we have no part in the quarrel between London and Washington.” Cartier grumbled.

“Ah but now we do play a part in it Cartier.” Macdonald said with a sour grin. “Thanks to that disgraceful excuse of a judge we can now be held responsible for the raids carried out by those Huns from the South. London had no part in it, we were the primary decision makers.”

“Not by our own volition.” Cartier said.

“Do you imagine the papers in New York and Philadelphia will see it that way? They already claim we hate them and support the South by inaction. What more proof do they need now? With the arch-annexationist Seward as the Secretary of State do you think they could see this as anything but a perfect chance to recoup their inevitable losses by turning their armies north?”

Cartier and Macdonald sat in silence as each mulled the idea over. The fear was not new to either of them, and each dreaded the thought of the absorption of the Province of Canada into the United States. They both had separate reasons but they were united, like so many Canadians, in that fear.

“For now though, we can only attempt to move the Assembly to action. In the meantime, I need support in actually planning how we can defend the Province should the worst come to pass.”

“So you want a staff?” Cartier asked.

“Perhaps we should think of it as more of a committee.” MacDonald said. “Little need yet to get Dorion totally up in arms. Besides, even the look of doing something will go a ways towards assuaging the politicians in London.”

“It is a thought.” Cartier said. “I certainly have a few men who could be relied upon to make a good contribution to any such effort.”

“I have a few in mind myself. We can compare notes tomorrow and consider appointments soon.”

The carriage trundled to a halt as the driver called out “Whoa!” and the passengers were jostled to a stop. Cartier grabbed his briefcase and stood up.

“More to be considered tomorrow.” Cartier said. “Good night John, get some sleep tonight. I think you’ll need all your strength in the weeks to come.”

The White House, Washington, the District of Columbia, December 1861

The fire was burning bright despite the hour being well past one in the morning. The various cabinet members were all looking drawn after yet another late night meeting regarding the ongoing events both at home and overseas. The United States Secretary of State William Seward stifled a yawn as he reached over and tapped yet more ash into a bowl which was nearly overflowing with the remains of the innumerable cigars he had already smoked that day. It was, he reflected, not a spectacularly good meeting.

The entire cabinet was present. Seated across from him was the Secretary of the Treasury Salmon Chase, the hard core abolitionist and beleaguered financer of the war. Next to Chase was seated the controversial Secretary of War Simon Cameron, the powerful Pennsylvanian was only in his position thanks to his influence of that state and Seward personally disliked the man. Next to Cameron was the Attorney General Edward Bates, Lincoln’s former rival in the presidential campaign. Directly beside Seward was the Postmaster General Montgomery Blair, scion of the politically powerful Blair family. Next to him sat the Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, the much suffering and greatly experienced political leader of the Union Navy. Then there was Secretary of the Interior Caleb Blood Smith, a personal favorite of Seward, while many accused him of simply being a place holder in Cabinet but Seward knew he could count on his political support. Finally there was the one damper on the whole meeting. Seward stole a glance down the table at his long-time rival, Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Charles Sumner.

Sumner, thanks to his contacts in Europe, and most importantly his well-established pro-Northern contacts in Britain, had managed to worm his way into the President’s good graces and the highest meetings of the cabinet. He sat at the end of the table looking just as tired as the other men in the room, but Seward could just detect the triumphant glow that he had whenever he cast a sideways glance at him. Not for the first time Seward groused internally about too many Secretaries of State in the capital.

Lincoln himself was at the head of the table looking haggard and care worn. His eyes were nearly hidden by deep bags, and he seemed scarecrow thin in his clothes that were ruffled as though he had slept in them. Nearby his secretaries, Nicolay and Hay recorded the evening’s minutes. Chase was continuing on his report about the financing of the war.

“The financial news from Europe is not cause for celebration. My agents confirm the banking houses there will not broker any loans to us. Not a dozen battles lost could have damaged our cause as greatly the current unpleasantness between ourselves and England.” Chase said ruefully “The Rothschild and Baring banking houses cannot be approached, and I hear even now that they are moving their assets from New York overseas. Our own banks are suffering as nervous investors are buying up everything from gold to saltpeter. I fear we shall soon have little specie at hand.”

“News from Europe is little improved on the diplomatic front I fear.” Seward said grumpily producing a pair of notes from his pocket. “The messages from Europe are resoundingly against us ‘According to the notions of international law adopted by all the Powers, and which the American government itself has often taken as the rule of its conduct, England could not by any means refrain in the present case from making a representation against the attack made on its flag, and from demanding a just reparation for it.’this from Berlin. ‘Although at present it is England only which is immediately concerned in the matter, yet, on the other hand, it is one of the most important and universally recognized rights of the neutral flag which is called into question we should find ourselves constrained to see in it not an isolated fact, but a public menace offered to the existing rights of all neutrals.’from Saint Petersburg.” Seward paused allowing his point to sink in. “It seems even the powers friendly to us disagree with the events in the Bahama Channel.”

“I fear then that the traitors will prove to be white elephants.” Lincoln said stirring from his attentive position to come into the conversation. “We cannot in good faith keep them at Fort Warren. It is perhaps best that we send them on their way, they will cause more damage here than I imagine they may be capable of causing in Europe.”

“This still has no bearing on the events off St. Thomas with the Dacotah.” Sumner said. There was a round of grumbles from the seated cabinet members.

“The public knows the truth of it and so must the world.” Welles said hotly “With the simply outrageous behavior of the British over those bandits from Canada I’m sure all can agree the British deserve what has taken place.”

“I have spoken to the Minister from France, Mr. Mercier, and he has made it quite clear that France’s position lays entirely with sympathy for Britain. Dayton has heard it from the French foreign minister himself, France may remain neutral, but it would be a benevolent neutrality in favor of Britain.” Seward replied.

“I have heard from my friend in London, Mr. Cobden.” Sumner pulled a note of his own from a pocket. “He writes to me saying ‘I am sure that your government means no offense towards the flag of Her Majesties Government, and we must deeply regret the events off St. Thomas, I believe our two nations may surely find peace.’ Not all Britain wishes for war.”

“There will be no war,” Lincoln replied “unless Britain is bent on having one.”

“But they will surely demand reparation.” Chase said.

“Reparation?” Welles demanded angrily. “Reparation be damned!”

Seward sighed internally. The polarization in the cabinet over the issue was becoming intolerable. As far as Seward could tell, the cabinet was split on forcing the issue with Britain like Welles, and those who wished to delay as long as possible. There was a third option, and he hated it as much as the others, but it was most likely the best. They would have to appease the British. Within reason of course, if a crisis was to be avoided it had to follow that the British should be bought off in some suitable manner.

Seward was about to speak when Lincoln interjected into what threatened to become a heated conversation.

“Gentlemen, I understand your outrage, and believe me I share in the anger at the death of brave American boys under the flag as much as anyone, but we must avoid dragging ourselves into another war. To that end we must mollify the British in some way.”

“And how do you propose to do that?” Welles said, a harshness still in his voice.

“We must release the rebels of course.”

“But that’s unthinkable!” The Secretary of the Interior burst out. “The public wouldn’t stand for it! It would be tantamount to an admission of weakness! Meekly submitting to John Bull in the face of all these outrages!”

“Now friend Smith I realize that the people will be displeased by such a gesture, but surely we can agree that with the international opinion so against us we have little to lose letting two such inconsequential gentlemen as these walk free?” There was again another round of grumbling around the table. Lincoln sighed. “Shall we put it to a vote?” He asked. The cabinet muttered its assent.

“All those in favor of releasing the commissioners immediately, please say aye.” Seward, Lincoln, and Chase affirmed. “Those against?” The remainder of the cabinet made a solid refusal.

“Well,” Lincoln said “the ayes have it.” There was laughter as each man of the cabinet vented some stress through Lincoln’s wit. He smiled with them suddenly seeming much less careworn than he had been.

“If you so wish it sir, the Cabinet will follow your decision.” Sumner said (presumptuously in Seward’s opinion) and there was a rumble of assent and Lincoln smiled at them.

“I merely think we must stand by American principles. We went to war with Britain in 1812 over this very thing, and it would be the height of hypocrisy now for us to claim the very right John Bull so bedevilled our forefathers with.”

“Quite right sir.” Blair said.

“Good. Seward, if you could be so kind as to begin formulating a note we could pass on to the government in London. I would also appreciate it if we could begin massaging the public to accept that this act will have to be undertaken.”

“I’ll see to it at once sir.” Seward said.

“Excellent. Now perhaps we can continue on to a less controversial item of conversation?”

Last edited:

Chapter 4: Family Honor

Chapter 4: Family Honor

Fulford homestead, Brockville, Canada West, December 9th 1861

The December snows had not come hard yet, but Hiram Fulford still trudged through the muddy path leading up to his home as though he had two feet of snow ahead of him. It had been a warm day and the ice had melted slightly, allowing the ground to suck at his boots. It was now he was glad for the newly issued boots passed out when the train had arrived in Brockville from Quebec to arm the Brockville Rifle Company. He even had a new uniform to wear with it instead of his old moth eaten red jacket that must have sat in the stores at Fort Wellington since 1812. His wife had said he cut a dashing figure in the uniform, but he still scraped his boots on the door siding, he’d get a broom to the back if he tracked dirt through the house.

The farm was a small well to do establishment, with a great barn off to one side sheltering a few cows and pigs alongside the family plough horse. A few chickens pecked around at the dirt near the barn looking for scattered seed, and he heard the clucking of the rooster off near the rear of the barn. His horse whickered at him from across the garden where it was stabled, and he smiled as he saw his little home for the first time in weeks. It didn’t look like much under the slate gray sky, but the long wooden cabin with an old addition had sat there for nearly one hundred years and he expected it to stand for another hundred more.

He stepped through the door and felt an immediate change from the weather outside. The fire in the hearth was roaring and he could smell a stew cooking in the pot. His three eldest daughters looked up from where they were mending clothes, and his second youngest son was fixing a pair of boots by the fire. Suddenly a tiny form rocketed toward him and latched onto his leg.

“Da! You're back!” ten year old George said burying his face in his father’s uniform trousers. The girls began to get up and greet him excitedly and his son stood up with a profound look of relief. His wife, Martha, looked up last with a smile on her face. She was trimming candles at the table and she put her tools down and walked over and pecked her husband on the cheek.

“Welcome home my dear.” She said affectionately grabbing his arm. Hiram smiled and kissed her back, he heard his daughters giggle but brushed it aside. It might be one of the last times he saw her.

“Only for a little while I’m afraid.” Hiram said ruffling George’s hair. “Could only convince the sergeant to let me come back for one day to drop off some money and collect some things. They’re not exactly overflowing with equipment in Brockville so I came to get Father’s old canteen and my own for William.”

“Where exactly is William?” Martha asked looking slightly worried.

“Out feeding some scraps to the pigs. He’ll be inside in a moment.”

“Good!” Martha said beaming “I’ve made stew for lunch with some smoked pork so we’ll fatten you up before the army takes you away from me, for now at least.” There was a slight strain in her voice as she said it, but she hid it well Hiram thought.

At that moment the door opened again and his eldest son, twenty-one year old William, strode in the door. His sisters eyes went wide and his brother seemed to openly gape. Young George let out a cry of delight. William did cut a dashing appearance in his uniform, he had made girls swoon before with his broad shoulders and quick wit but now with the sharp red uniform and the ghost of a moustache on his lips and his dark hair framed by a service cap he seemed the picture of military discipline. God willing he lets the damn thing get dirty if his life is on the line, the elder Fulford thought with mild exasperation as he recounted in his head the supreme care his son had taken in keeping the uniform clean. The sharp words of the company sergeant had helped though.

William stood erect grinning like a conquering hero for a moment, before a purely boyish grin cut through his military demeanor and he exclaimed.

“Hello ma! Is that lunch I smell?”

His sisters and brothers all laughed and Hiram himself grinned. Martha shook her head and walked over and took him by the arm while congratulating him on how wonderful his uniform looked. She also called for their daughter Dorothy to stir the stew pot. The whole family seated themselves now and the children set the table while Hiram and Martha discussed how the farm would be cared for while he was gone.

“And you must be sure to keep my brother Bill informed about the goings on here. He’ll look after you in case anything goes wrong. We’ve always looked out for each other Bill and I, so he will be sure to keep an eye on you. Especially little George here.” Hiram said affectionately reaching over to tickle his son as he ladled stew into a bowl. The younger laughed and the two brothers grinned and reached over to join in as they sat down for lunch. Martha sliced bread for them all and placed a plate of butter beside them on the table.

They all ate happily for a few minutes. Until George spoke up.

"Why is everyone off drilling?" George said tasting the unfamiliar word on his lips.

"In case we have to fight the Americans son." Hiram said around a mouthful of stew.

True, there wasn't a war on, but that hadn't stopped the many existing militia companies from turning out to drill at the news of the Border raids and the Trent incident. Though the Provincial Government had called out the embodied militia at the end of October most men weren't under arms officially. That wouldn't stop anyone from doing their part or preparing, especially not in the heart of Loyalist country around Kingston and on the river.

“Da, why do you have to go fight the Americans?”

“Well George, it’s because they insulted the honor of the Queen.” Hiram said through a mouthful of beef, no reason not to eat and talk. George thought about that for a moment.

“But why do you have to save her honor?” He asked again.

“The Queen is our sovereign and she rules over us. By insulting the Queen they make us look silly and you don’t like being made to look silly do you?”

“No.” George said wrinkling his nose. He was quiet for a few more minutes then asked another question.

“How come they are coming to fight us if they just insulted the Queen?”

“George would you shut up and eat lunch.” William said with exasperation.

“William! Mind your manners!” Martha scolded.

“It’s ok son, asking questions is how you learn. George, the Americans have killed British subjects on the sea, now they attack British ships as well. They want a war, a politician named William Seward has been saying for years how Canada should become part of the United States. Now it looks as though he means to do it by force, conquer us against our will.”

“Why would he want to do that?” George asked.

“Because that’s what nations do sometimes George, they fight each other because they want more land. Like when the Hendersons and the McCleans argued over who that field belonged to.”

“But why can’t the Americans and the British settle their differences like the neighbors did?”

“There’s no court that a country can appeal to son.” Martha said gently “Sometimes things get violent. Like when you and your brother fight.”

“We do not!” George exclaimed defensively.

“Says you.” His elder brother said peevishly. George stuck out his tongue and his sisters laughed. Martha scolded each of them in turn and the giggling subsided as they tucked into their food again. Laughing continued for a few minutes before his middle son, Alfred, spoke up.

“So this is like when grandpa fought the Americans in 1812?” He asked.

“Much like it.” Hiram said taking another piece of bread and smothering it with butter. “And my grandpa before him. He fought the Americans all the way back in 1777 as a Loyalist to the Crown. After the war they chased him from his land so the Crown gave him land here. Then in 1812 the Americans came north again and tried to take our land from us. It looks like they mean to do so again, and that is why your brother and I are off to join the militia.”

“So we can drive the Americans south with their tails between their legs!” George exclaimed triumphantly stabbing his meat with a knife for emphasis.

“Don’t get too excited for war George. Your grandpa never spoke of it to me when he was still alive, and my grandpa rarely spoke of it at all, save one story about gutting a rebel at Assunpink.”

“Hiram! Don’t say such things in front of the children!” Martha cried giving him a stern scolding for his outburst.

“I won’t say much more dear, but war is coming. The little ones should know it may not be pretty.”

She scolded him with a look which suggested they would speak more on it later and they continued their meal. As they did George reflected on how happy his family looked around the table, he wished he could stay and just be with them, but he could never look his friends who went and fought in the eye afterwards, especially not with the legacy of his grandfather to uphold, it would stain the family honor.

He looked to little George again and gave a very fond smile at the boy. If only we all had a child’s innocence, he thought, we could save the world a great deal of conflict.

-----

This is by and large just a rehash of an old narrative bit I couldn't really find a place for in the last chapter. So this is just a bit of a nostalgia piece for me without much narrative value to the TL as a whole, bit of an indulgence if you will

A proper update and a fully created index for this thread should be out come Tuesday.

I really enjoy your version of Lincoln, if the movie is any indication you've pretty well nailed his tone.

I really enjoy your version of Lincoln, if the movie is any indication you've pretty well nailed his tone.

I can't help but read his dialogue in Daniel Day Lewis' voice. Which is a very good thing.

I really enjoy your version of Lincoln, if the movie is any indication you've pretty well nailed his tone.

I can't help but read his dialogue in Daniel Day Lewis' voice. Which is a very good thing.

Well I won't lie, Daniel Day Lewis was a huge influence on how I've come to portray Lincoln. His sense of humour and his quips were simply legendary! Lewis probably captured it as well as we are likely to see in our lifetime. I honestly have to reign in from using some of his quips when I'm writing him lest I get carried away

Another character who I'm putting lots of effort into portraying well in the narrative bits is John A Macdonald. His wit was pretty sharp and he was quite the speaker, even when he was insensible and drunk!

Chapter 5: A Stormy Sea Pt. 1

Chapter 5: A Stormy Sea Pt. 1

“Do not be quickly provoked in your spirit, for anger resides in the lap of fools.” Ecclesiastes 7 verse 9.

“While the British Cabinet was still debating an adequate response to the events of the Trent, news of the Dacotah-Terror incident reached London on December 5th. This further muddied the waters of Britain’s response to the incident. Palmerston became increasingly convinced that the North meant to distract themselves from defeats in the South by provoking Britain writing that “Every report, public, official, and private that comes to us from the Northern States of America tends to show that our relations with the Washington government are on the most precarious footing and that Seward and Lincoln may at any time and on any pretense come to a rupture with us.” Further adding “There can be no doubt that their policy is to heap indignities on us, and they are encouraged to do so by what they imagine to be the defenceless state of our North American Provinces.”

The Cabinet was coming around to Palmerston’s view, and in fact many felt that they had no choice to press forward for a harsh response, especially since to lose the North American colonies would cause a staggering loss of face. It was seen as imperative to fight as “England would not be great, successful, courageous England if she did not”. Clarendon wrote as the crisis deepened that “What a figure we shall cut in the eyes of the world if we tamely submit to these outrages when all mankind will know that we should unhesitatingly have poured our indignation and our broadsides into any weak nation and what an additional proof it will be of the universal belief that we have two sets of weights and measures to be used according to the power or weakness of our adversary. I have a horror of war and of all wars one with the U.S. because none would be so prejudicial to our interests, but peace like other good things may be bought too dearly and it never can be worth the price of national honor.”

Newcastle in 1860 had discussed such an event with Seward during the Prince of Wales trip to North America. When Seward had expressed disbelief that Britain might ever dare go to war over the North American colonies Newcastle answered simply. “Do not remain under such an error. There is no people under Heaven from whom we should endure so much as from yours, to whom we should make such concessions…But once touch us on our honour and you will soon find the bricks of New York and Boston falling about your heads.” The proclamation would prove itself startlingly prophetic.

News of the two incidents having arrived so close together, the Cabinet had not dispersed before the coming of December, and instead was still gathered in London where it stepped up its emergency meetings to make preparations for a conflict that all expected would come. Its first priority had been to ban the sales of arms and ammunition to the North on December 3rd, as Lord Stanley the Postmaster General wrote “If we are to be at war it is as well not to let them have improved rifles to shoot us with.” On the 7th a special war committee had convened, its members were Palmerston, Somerset, Lewis, Newcastle, Lord Granville, lord president of the council, and the Duke of Cambridge. Orders went out that the forces placed on standby were to be dispatched to North American immediately; while the divisions at Aldershot and Shorncliffe were to be brought up to full strength and the steam reserve was opened (and when one considers that this was before the adoption of a general staff, that there was no intelligence department, and no regular procedure for cooperation between the service departments these quick decisions are no mean feat)[1].

In the meantime, a political response was to be considered. Though the details of the events transpiring between the Dacotah and Terror remained unclear (Hutton’s full report would not arrive until a week later) it was clear that some kind of action would need to be taken.

The Law Officers of the Crown had written a memorandum advising the Cabinet on the opinion of Maritime Law which stated that Wilkes would be within his rights to search the vessel or to carry it off to be adjudicated in an admiralty court, but he would have no right to simply search the vessel and carry off any of the passengers as prisoners. The death of Captain Williams merely added to the outrage of the event. The incident between two warships however, seemed more readily clear cut, and with the arrival of Hutton’s report there is a general agreement that stern diplomatic measures must be taken, while military preparations were stepped up.

First however, they must wait for word from Washington…”Empire and Blood: British Military Operations in the 19th Century Volume IV.

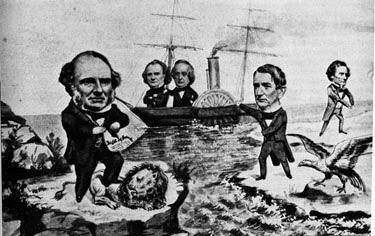

Contemporary illustration of the Trent Affair

“The decision on how to respond to the Dacotah-Terror incident was one which did not come easily to the Lincoln administration. Public outrage over the death of American sailors was acute with anti-British riots breaking out in Boston and New York over the news. The British consul in Boston was forced to seek refuge in a police station which the mob repeatedly attempted to enter, and it wasn’t until the next morning that he could return home, under police escort.

The Cabinet itself was torn on their response. Welles as the Secretary of the Navy was particularly infuriated over the damage inflicted upon an American warship and he was adamant that Britain be called into account for her actions. Cameron, as Secretary of War, largely sided with Welles on the matter. However, neither was willing to promote the belief that there would be war. The remainder of the Cabinet was equally opposed to the idea of war. Few in fact believed it was possible at first. The only dissenting opinion remaining was Seward.

He was however, checked by his rival Charles Sumner, Chairmen of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Sumner, a lawyer by trade, had been born in Boston to a poor family but had rapidly worked his way up in the world with a combination of skill and cunning intellect. He had travelled Europe in the 1830s and returned in 1840 to practice law and lecture at Harvard. An avowed abolitionist since his youth he spoke out against slavery with increasing bombast, opposing the Mexican War on those grounds and had only hardened in his outspoken views on the slave states of the South. In his antebellum career he denounced the Slave Power of the South and spoke openly of the Crime Against Kansas in powerful speeches. This earned him the ire of many powerful Southern politicians, especially in South Carolina. This resulted in the infamous attack on the Senate floor where he was beaten into unconsciousness by South Carolina representative Preston Brooks. The event in itself was polarizing across the nation, but for Sumner it merely entrenched his radical views and he returned to the Senate in 1859 a staunch member of the Radical wing of the new Republican Party.

Sumner and Seward had long been rivals, and this rivalry was a source of extreme friction between the Secretary of State and the Foreign Relations Committee Chairman. Lincoln for his part had taken Sumner into his confidence, putting much trust in Sumner’s position as with his connections in British society abroad. Seward wished to pursue a policy of immediate appeasement to give “every satisfaction consistent with honor and justice” to prevent an escalation. Sumner advised Lincoln to adopt a policy of wait and see. He firmly believed that they should give time for tempers to cool on both sides of the Atlantic, and urged Lincoln to adopt a course which could satisfy honor on both sides. He was quick to blame Seward for any ill feeling between Britain saying “The special cause of the English feeling is aggravated by the idea on their part that Seward wishes war” which in light of many of Seward’s previous displays of bellicosity struck Lincoln as a reasonable source of tension. In such a fashion Sumner was able to maneuver his way into Lincoln’s trust on the issue and become his main advisor during the crisis.

Lincoln was hopeful that Sumner’s approach would sweep the whole affair under the rug. He was eager for some sort of reconciliation with Britain, but he would not sacrifice national honor to get it. Together he and Sumner composed a note to the British cabinet informing them that the action undertaken by Wilkes and McKinstry were not sanctioned by the government. It was hoped that this letter would calm the feelings of the British.

The arrival of despatches and papers from Britain on the 13th of December seemed to give lie to the idea that any sort of decent compromise could be had. News of the outrage in Britain itself simply fueled the fires in the American press over the matter. Lincoln’s refusal to publicly comment on the crisis had not prevented many editors from doing so themselves. As the Sunday Transcript in Philadelphia declared “In a word, while the British government have been playing the villain, we have been playing the fool. Let her now do something beyond drivelling – let her fight! We have met Britannia on the field and have brought low the best of British troops, and even humbled that mighty armada of the Royal Navy. Let Britain now – if she has a particle of pluck, if she is not as cowardly as she is treacherous – she will again meet the American people on land and sea as they long to meet her once again, not only to lower the red banner of St. George but to consolidate Canada with the Union.” In fact the American minister to Russia, Cassius Clay, may have accurately captured the feeling of many Americans at the time when he wrote “They hope for our ruin! They are jealous of our power. They care neither for the South nor the North. They hate both.”

These cries were taken up in papers all throughout New England and the Mid-West, with the New York Herald being perhaps the loudest in its sentiments for expressing war. The public opinion was sliding slowly towards confrontation…” Snakes and Ladders: The Lincoln Administration and America’s Darkest Hour, Hillary Saunders, Scattershot Publishing, 2003

Charles Sumner, Seward's earnest rival.

“Lincoln’s message to the Cabinet was received in London on the 19th. The Cabinet’s reaction was less than pleased by the contents of the letter. Their interpretation of the increasingly hostile articles appearing in American newspapers was that Lincoln could not be counted upon to reign in his own officers or citizens from potential reprisals against British citizens.

In response a memorandum was debated to properly address the British governments concerns. After a week of deliberations they decided on what would become known as the December Ultimatum. The document had four points:

1) The immediate release of the Confederate commissioners

2) The dismissal of both Captain Wilkes and Captain McInstry from naval service

3) The issuing of a formal and public apology on the part of the United States government for the actions undertaken by members of its Navy

4) The United States would pay for the damages to HMS Terror and would provide financial restitution for the damages done aboard RMS Trent. The amount to be paid would be determined solely by Her Majesties Government

The Cabinet felt these demands to be reasonable, and Queen Victoria was in agreement. How much attention the Queen paid to the points of the ultimatum is not known. What is known is that Victoria was deep in mourning at this point and had been shut away in Windsor Palace for over a month having little to do with the running of government. Some speculate that had Albert still been alive the Royal Couple may have done more to soften the letter of the British response, but with the nature of the provocations and misunderstandings having taken place over October and November this is of course, up for debate.

The Cabinet agreed that the rejection of this document would lead to an immediate suspension of diplomatic relations between the two nations, and in effect, war. The message was dispatched on the 27th of December with enclosed orders for Lord Lyons of the British legation.

Britannia awaited an answer…”Empire and Blood: British Military Operations in the 19th Century Volume IV.

Britain awaits an answer, Puck December 1861

[1] Here I’m paraphrasing Kenneth J. Bourne. I got these details from an excellent article he did on the subject. It seems that the British had made rather serious preparations for a potential conflict, ones that I want to make more front and center this time around.

Last edited:

1) The immediate release of the Confederate commissioners

2) The dismissal of both Captain Wilkes and Captain McInstry from naval service

3) The issuing of a formal and public apology on the part of the United States government for the actions undertaken by members of its Navy

4) The United States would pay for the damages to HMS Terror and would provide financial restitution for the damages done aboard RMS Trent. The amount to be paid would be determined solely by Her Majesties Government

The Cabinet felt these demands to be reasonable, and Queen Victoria was in agreement.

the point in bold is where the British step from reasonable demand to folly... the other 3 are actually reasonable, but demanding the dismissal of officers is where things are going to become impossible for the Americans to respond in a manner the British apparently feel necessary. They wouldn't of in 1812 and didn't even when the Chesapeake -Leopard affair in 1807 until the US ship was fired on (while it was helpless to respond).

So the British just made war inevitable. Sure you can blame over zealous American officers, but you can't blame American policy. You can blame British policy. Although the officer in charge of the American boarding party should face court martial (I didn't say automatic conviction, I mean a trial).

TFSmith121

Banned

Interesting contrast with 1811

Interesting contrast with 1811, when the President-Little Belt incident occurred, in wartime, and ended with 32 RN casualties and a British warship one broadside from surrender to the USN; amazingly enough, Perceval didn't order any ultimatums.

That's the thing with Trent Affair timelines; one needs much more than a single incident or two or three, even with Palmerston in charge, to get war; and given Pam's ability to read a balance sheet in 1864 when the Prussians and Austrians essentially took control of the Baltic exits (slightly more important to Britain than just about anything in the Western Hemisphere), even with Pam as the PM, the march of folly needs a deeper foundation and more going on...

Pam knew the UK could not defend Denmark against a continental threat in 1864 despite the bluster, he and everyone else of importance knew the UK could not defend BNA in 1862 (including Wolseley, for crying out loud) and everyone knew the BNAers would not.

Best,

the point in bold is where the British step from reasonable demand to folly... the other 3 are actually reasonable, but demanding the dismissal of officers is where things are going to become impossible for the Americans to respond in a manner the British apparently feel necessary. They wouldn't of in 1812 and didn't even when the Chesapeake -Leopard affair in 1807 until the US ship was fired on (while it was helpless to respond).

So the British just made war inevitable. Sure you can blame over zealous American officers, but you can't blame American policy. You can blame British policy. Although the officer in charge of the American boarding party should face court martial (I didn't say automatic conviction, I mean a trial).

Interesting contrast with 1811, when the President-Little Belt incident occurred, in wartime, and ended with 32 RN casualties and a British warship one broadside from surrender to the USN; amazingly enough, Perceval didn't order any ultimatums.

That's the thing with Trent Affair timelines; one needs much more than a single incident or two or three, even with Palmerston in charge, to get war; and given Pam's ability to read a balance sheet in 1864 when the Prussians and Austrians essentially took control of the Baltic exits (slightly more important to Britain than just about anything in the Western Hemisphere), even with Pam as the PM, the march of folly needs a deeper foundation and more going on...

Pam knew the UK could not defend Denmark against a continental threat in 1864 despite the bluster, he and everyone else of importance knew the UK could not defend BNA in 1862 (including Wolseley, for crying out loud) and everyone knew the BNAers would not.

Best,

Last edited:

Good to see this back indeed. The previous version was shaping up to be a fine timeline and I've no doubt this one will follow suit.

Thank you! I'm hoping to do one better than the previous one so I'm trying to keep things strong out of the gate.

the point in bold is where the British step from reasonable demand to folly... the other 3 are actually reasonable, but demanding the dismissal of officers is where things are going to become impossible for the Americans to respond in a manner the British apparently feel necessary. They wouldn't of in 1812 and didn't even when the Chesapeake -Leopard affair in 1807 until the US ship was fired on (while it was helpless to respond).

So the British just made war inevitable. Sure you can blame over zealous American officers, but you can't blame American policy. You can blame British policy. Although the officer in charge of the American boarding party should face court martial (I didn't say automatic conviction, I mean a trial).

I wasn't entirely satisfied with the way I handled the ultimatum originally, so I felt that changing it was necessary to make it politically impossible for the US to accede to.

The second point is the least reasonable, but given Palmerston's history (pushing for the fall of Sevastopol and harsh terms on the Russians, pushing for the burning of the Summer Palace and more, desiring a harsh ultimatum OTL during the crisis) so I think it's in line with Palmerston's character to make such an arrogant command. Without Prince Albert, or a sympathetic voice in the British Cabinet for American interests I think that it's probable something like that would slip through to the ultimatum. Factor in British anger and I can see it as being seen as somehow a good idea.

From a practical perspective I would say that making the whole series of demands an ultimatum (which they were close to doing OTL) would have been a failure of policy in and of itself. Adding the really arrogant point is rubbing salt in the wound.

From a narrative perspective if I don't make the ultimatum harsh enough Lincoln could probably find a way to soften the situation to his advantage

Fortunately (for the TL at least) Palmerston is not the type to go for half measures when he feels like being vindictive.

TFSmith121

Banned

And yet Pam recognized reality in 1864

And yet Pam recognized reality in 1864.

Best,

Thank you! I'm hoping to do one better than the previous one so I'm trying to keep things strong out of the gate.

I wasn't entirely satisfied with the way I handled the ultimatum originally, so I felt that changing it was necessary to make it politically impossible for the US to accede to.

The second point is the least reasonable, but given Palmerston's history (pushing for the fall of Sevastopol and harsh terms on the Russians, pushing for the burning of the Summer Palace and more, desiring a harsh ultimatum OTL during the crisis) so I think it's in line with Palmerston's character to make such an arrogant command. Without Prince Albert, or a sympathetic voice in the British Cabinet for American interests I think that it's probable something like that would slip through to the ultimatum. Factor in British anger and I can see it as being seen as somehow a good idea.

From a practical perspective I would say that making the whole series of demands an ultimatum (which they were close to doing OTL) would have been a failure of policy in and of itself. Adding the really arrogant point is rubbing salt in the wound.

From a narrative perspective if I don't make the ultimatum harsh enough Lincoln could probably find a way to soften the situation to his advantage

Fortunately (for the TL at least) Palmerston is not the type to go for half measures when he feels like being vindictive.

And yet Pam recognized reality in 1864.

Best,

he and everyone else of importance knew the UK could not defend BNA in 1862 (including Wolseley, for crying out loud)

I'd put a heavy asterix on that. All the relevant data points to the fears of a United States, not one embroiled in a civil war, being able to overrun Canada. Otherwise the views of those in power are much more sanguine.

They had fairly good reason to be.

and everyone knew the BNAers would not.

Except the people in British North America themselves and the Commissioners appointed directly to assess the possibility of defence in the Province of Canada themselves in 1862 apparently.

And yet Pam recognized reality in 1864.

More than a minor difference considering Denmark set itself up for the war by giving Prussia and Austria a casus-beli which Britain couldn't refute.

Now had the Austrians boarded a British ship and taken some Danish politicians off the British perception of the issue might have been a tad different.

TFSmith121

Banned

Wolseley is on record when sent in 1861 that he

Wolseley is on record when sent in 1861 that he and rest of the force would be dead or prisoners early in 1862; of course, compared to being cooped up in Melbourne for a month as she tried to cross the Atlantic, presumably death or capture would be a preferred option.

Yeah, all 25,000 Upper and Lower Canadians the British actually expected would show up by the end of 1862, along with the roughly ~6,000 Maritimers - who could not, of course, been ordered to serve outside of their home colonies.

Best,

I'd put a heavy asterix on that. All the relevant data points to the fears of a United States, not one embroiled in a civil war, being able to overrun Canada. Otherwise the views of those in power are much more sanguine.

They had fairly good reason to be.

Except the people in British North America themselves and the Commissioners appointed directly to assess the possibility of defence in the Province of Canada themselves in 1862 apparently.

Wolseley is on record when sent in 1861 that he and rest of the force would be dead or prisoners early in 1862; of course, compared to being cooped up in Melbourne for a month as she tried to cross the Atlantic, presumably death or capture would be a preferred option.

Yeah, all 25,000 Upper and Lower Canadians the British actually expected would show up by the end of 1862, along with the roughly ~6,000 Maritimers - who could not, of course, been ordered to serve outside of their home colonies.

Best,

I wasn't entirely satisfied with the way I handled the ultimatum originally, so I felt that changing it was necessary to make it politically impossible for the US to accede to.

The second point is the least reasonable, but given Palmerston's history (pushing for the fall of Sevastopol and harsh terms on the Russians, pushing for the burning of the Summer Palace and more, desiring a harsh ultimatum OTL during the crisis) so I think it's in line with Palmerston's character to make such an arrogant command. Without Prince Albert, or a sympathetic voice in the British Cabinet for American interests I think that it's probable something like that would slip through to the ultimatum. Factor in British anger and I can see it as being seen as somehow a good idea.

From a practical perspective I would say that making the whole series of demands an ultimatum (which they were close to doing OTL) would have been a failure of policy in and of itself. Adding the really arrogant point is rubbing salt in the wound.

From a narrative perspective if I don't make the ultimatum harsh enough Lincoln could probably find a way to soften the situation to his advantage

Fortunately (for the TL at least) Palmerston is not the type to go for half measures when he feels like being vindictive.

I didn't say you are wrong however, and definitely powerful nations make grand miscalculations routinely in history (including the US, sigh), but future historians are not going to be kind to the British government of the day for getting themselves involved in a risky, expensive war due to arrogance.

And the original British response was (before it was edited by Prince Albert) almost bad enough to push things too far in OTL

TFSmith121

Banned

Or if the Austrians or Prussians had gotten

Or if the Austrians or Prussians had gotten into an incident with a British warship that ended with 32 RN dead or wounded, surely that would have led to war.

Oh wait.

Best,

More than a minor difference considering Denmark set itself up for the war by giving Prussia and Austria a casus-beli which Britain couldn't refute.

Now had the Austrians boarded a British ship and taken some Danish politicians off the British perception of the issue might have been a tad different.

Or if the Austrians or Prussians had gotten into an incident with a British warship that ended with 32 RN dead or wounded, surely that would have led to war.

Oh wait.

Best,

I didn't say you are wrong however, and definitely powerful nations make grand miscalculations routinely in history (including the US, sigh), but future historians are not going to be kind to the British government of the day for getting themselves involved in a risky, expensive war due to arrogance.

And the original British response was (before it was edited by Prince Albert) almost bad enough to push things too far in OTL

Yeah, even contemporaries are going to be harsh on them IMO since it will be seen in a light worse than the Crimean War I think, with no Indian Mutiny to bask in, in the aftermath to deflect problems.

I actually have plans for two irreverent playrights to make a point of referring to how pointless it all was...

Or if the Austrians or Prussians had gotten into an incident with a British warship that ended with 32 RN dead or wounded, surely that would have led to war.

Oh wait.

Apples and oranges.

Nor would those nations have been ones Britain felt a particular grudge against or felt they could have pushed around without consequence.

TFSmith121

Banned

Polish up the handle of the big front door?

Polish up the handle of the big front door?

Or the very model of a modern major general?

Interesting sidelight on popular culture perceptions of the British armed forces in the period...

Best,

Yeah, even contemporaries are going to be harsh on them IMO since it will be seen in a light worse than the Crimean War I think, with no Indian Mutiny to bask in, in the aftermath to deflect problems.

I actually have plans for two irreverent playrights to make a point of referring to how pointless it all was...

Polish up the handle of the big front door?

Or the very model of a modern major general?

Interesting sidelight on popular culture perceptions of the British armed forces in the period...

Best,

Threadmarks

View all 157 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

The New World Order 1866 Part 4: The Mexican Empire Chapter 126: The Balance of Power in North America Chapter 127: What If? Chapter 128: 1866 A Year in Review Chapter 129: Grasping at Thrones Chapter 130: Plots in Motion Chapter 131: Trans-Atlantic Troubles Chapter 132: A Want of Preparation

Share: