So, both the American and Soviet rocket scientists are working towards a lunar mission. But they do not work in a vacuum, and global politics are about to exert an influence in this week's...

Part III Post #9: Year of Crisis

1974 dawned full of promise for Vladimir Chelomei. Although his hated rival Mishin had launched a second Chasovoy space station the previous year, as well as two successful crewed flights to occupy the station, Chelomei’s own moves meant that his political stock was once more on the rise. In September 1973 he had obtained a significant victory through the launch of air force pilot instructor Lidiya Kotova on a week-long Orel mission, claiming the title of First Woman in Space for the Soviet Union - a title that Mishin had spectacularly failed to secure a decade earlier with Zarya-3. On top of this, Mishin’s efforts to upgrade his Zarya capsule into a moonship were stalling in the face of continuous weight growth problems, whilst shortages of materials and critical components delayed work and morale and productivity amongst his workers continued to decline. Chelomei faced these difficulties too, but had been more successful in greasing the right palms to free up his supply lines, and by January 1974 he had a prototype Sapfir capsule ready to launch on an unmanned test flight.

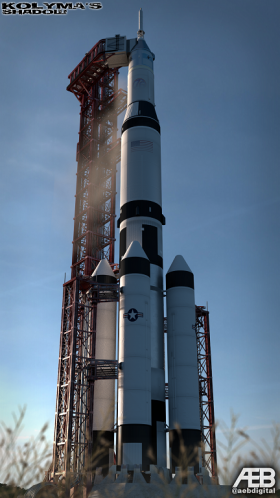

Lift-off for Sapfir-1 (aka Kosmos-121) on an unmanned test flight around the Moon, January 1974.

The launch of Sapfir-1 (officially dubbed Kosmos-121) atop a Proton rocket was a complete success, injecting the spacecraft into a trans-lunar free-return trajectory that mirrored that planned for the manned mission. The capsule was mated to an AO module smaller than that planned for operational missions, as the full-sized module would require upgrades to the Proton launch vehicle that Kulik had yet to deliver. The substitute AO was however more than capable to support the capsule for this initial mission, and telemetry was picked up by tracking stations across the USSR and by specialised ships on the high seas all the way up to day 2, when the spacecraft passed behind the body of the Moon. A tense few hours followed before Sapfir’s signal reappeared on the other side, to cheers from Chelomei’s mission controllers.

The return leg of the journey proceeded smoothly, but the most critical part of the mission remained: re-entry of the Earth’s atmosphere from lunar velocities. Unlike Mishin with his double-skip Zarya mission profile, Chelomei had chosen the simpler but more demanding direct re-entry option. Would Sapfir’s heat shield be able to withstand these forces? Would the deceleration generated remain within limits that a cosmonaut could survive? Chelomei had calculated these factors in theory, but only direct experiment could prove the answers.

Those answers were delayed somewhat as the hunt for exactly where the capsule had touched down was carried out over the next two days. When the spacecraft was finally located deep in the remote taiga, the recovery team found that Sapfir had indeed survived the fierce heat of re-entry intact, with the the on-board instruments recording survivable conditions throughout the landing.

Although Chelomei was increasingly certain that the job of flying to the Moon and back was survivable, the job of General-Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was proving a more difficult proposition. After eight years in the role, Shelepin’s reputation was beginning to tarnish. The massive military build-up and policy of confrontation with the West that his regime had initiated had at first appeared to have achieved their objectives, strengthening the USSR’s grip on its Warsaw Pact satellites and ensuring that Soviet views were treated with appropriate seriousness in international affairs. A combination of military intimidation and targeted espionage campaigns had seen Albania and Yugoslavia forced back into the Moscow camp, whilst Castro’s Cuba had been left to wither on the vine, forcing China to commit more and more of its own limited resources to propping up the regime there. Relations with China itself remained frigid, but where he had been disdainful of Khruschev, Mao had learnt a wary respect for Shelepin’s strength.

Successful as this policy of militarisation appeared on the surface, the massive diversion of resources it entailed soon began to have a negative impact. This diversion, along with the re-imposition of Stalinist controls of the economy, had seen the strong growth that the Soviet economy had enjoyed since the fifties - even the ‘growth’ reported in official government statistics - falter and stall. By 1974, economic growth was stagnant or in a mild contraction, but the quality of life of Soviet citizens had already been declining for several years as the civilian economy was disproportionately hit. Agricultural production in particular was in decline, and with Shelepin reluctant to rely upon Western food imports (and indeed many in the West being reluctant to deal with him), bread queues became a fact of life for anyone not able to access the specialist Communist Party shops. Food riots became frequent occurrences in 1972 and 1973, especially in the Baltic and Caucasian republics, which were already chafing over Shelepin’s focus on the Russian heartland at the expense of the peripheral republics. These riots were brutally put down by the Red Army and went unreported in the state media, but the scale of atrocities often became amplified in retelling over furtive black market exchanges. The KGB and Army between them were able to keep a lid on dissent within the general population, but as the situation deteriorated there were increasing murmurs of discontent amongst the governing apparatchiks themselves.

On 17th April 1974, as Shelepin was being driven to his out-of-town dacha on the edge of Moscow, he suddenly found himself short of breath and sweating profusely. Alerted by the General Secretary’s banging on the glass between them, his driver immediately swung the armoured ZiL around and rushed back into the city centre, towards the Central Clinic Hospital. Upon arrival the doctors quickly ascertained that Shelepin had suffered a massive heart attack. Despite their best efforts to revive the Soviet leader, Shelepin fell into a coma, before finally dying of a second heart attack on 19th April.

The following weeks were tense as various factions within the Soviet hierarchy manoeuvred for influence. Pravda and Radio Moscow were reporting that the General Secretary had passed from natural causes, but both inside and outside of the Soviet Union there were those who found the circumstances highly suspicious. Shelepin had been only 55 years old at the time of his death, and had appeared to be in overall good health. For many therefore, the only question remaining was had it been the KGB, the Army, or some faction of the inner Party that had managed to do him in? Whoever it was (assuming it was indeed an assassination), they had apparently either acted without putting a follow-up move into place, or had lost their nerve, leaving a paranoid vacuum of power whilst all sides attempted to secure their own strongholds of support in preparation for the inevitable move of one of the other factions. In the meantime, day-to-day running of the government was left to the Chairman of the Council of Ministers, a non-entity Shelepin appointee named Maxim Teplov, who had risen through the Party ranks on the back of a solid if unspectacular career in industrial management at the regional and national levels. He had held little real power under Shelepin, and continued to hold little power as the Politburo factions squared off against one another in the final days of April.

The power vacuum in the Kremlin was greeted with fear by many in the West, but for others was seen as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. One of the first to move was Miko Tripalo, the head of the Croatian Communist Party. Croatian nationalism had been brutally suppressed following the 1969 coup which had seen Josip Broz Tito, a Croat, replaced by the pro-Moscow Aleksandar Ranković. Tripalo had managed to retain his position, but remained loyal to the memory of Tito and nursed a quiet resentment of what he saw as the subordination of Croatia and the other republics to Serbia within the Federation. Tripalo had quietly established contact with a network of Croatian nationalists in civil society and within the Yugoslav People’s Army, but with Red Army troops stationed throughout the country any uprising was liable to be immediately squashed at Shelepin’s order. However, with the Soviet leader out of the picture and the Moscow leadership in chaos, Tripalo and his allies seized their chance.

On May Day 1974, the regional Communist Parties of Croatia and Slovenia declared their secession from Yugoslavia pending the creation of a more just and equitable Federal Constitution, and called for all loyal citizens in the People’s Army to return home and defend their lands. Serbian troops and those professing loyalty to Belgrade were quickly rounded up, but Soviet forces were left alone, with Tripalo loudly proclaiming his support of the USSR, the Warsaw Pact and the international worker’s struggle. With their leaders in Moscow struggling to keep up with events, and no-one quite sure if official Soviet policy was still to support Ranković after the death of Shelepin, the Red Army stayed put. Belgrade’s forces would have to act alone to quell the rebellion, and in a matter of weeks the situation had deteriorated into a bitter, bloody civil war.

With Yugoslavia descending into chaos, several leaders in Eastern Europe began looking nervously to their own opposition groups. With Moscow apparently paralysed, could they also be hung out to dry in the event of an uprising? In Romania, Hungary and Bulgaria, the governments moved to eliminate this risk with a brutal pre-emptive crack-down on anyone who’d so much as hung a picture of Lenin crookedly. The governments in Czechoslovakia and Poland were more cautious, entering into quiet, behind the scenes talks with their radicals about how the system might be reformed to better meet the aspirations of the population. The DDR took a middle path between these two options, with the increasingly infirm Ulbricht at first ordering a crack-down, only to find his support within the SED had withered during his illness. He was instead forced to retire in early June, to be replaced as head of the Party by Horst Sindermann. As with Tripalo, Sindermann moved quickly to proclaim his loyalty to Moscow (as a strategically critical location with by far the greatest concentration of Soviet forces outside the Motherland, any other course would have been suicide), whilst also promising to “re-invigorate the DDR’s economic and political life in the pursuit of true Socialism”. Whilst these developments behind the Iron Curtain were viewed with a mixture of excitement and alarm by Western governments, the most dangerous phase of the upheaval was still to come.

By July, the various factions in the Politburo had agreed to form a true Collective Leadership with a rotating Chairmanship governing the body. However, whilst this gave the appearance of stability, in reality it was the result of a deadlock that could collapse at any moment, should any of the factions decide that it had a chance to gain the upper hand over their rivals. The day-to-day running of the Soviet empire therefore remained with Teplov and the Council of Ministers, with only the most important of policy issues making it through the Politburo. Soviet foreign policy remained effectively frozen, and so it was the the governments of Egypt and Syria decided to take action.

Since their defeat by Israel in 1967, the two Arab nations had been rebuilding their forces and waiting for an opportunity to strike back at their hated enemy. Shelepin had supported their governments as a powerful counterbalance to American influence in the region, and had supplied them with large quantities of sophisticated Soviet weapons systems and training, but had also acted to restrain his allies from taking action prematurely. Shelepin’s objective had been to spread Soviet influence through constant, steady pressure rather than to strike hard and risk a massive US reaction, but with Shelepin gone Sadat and al-Assad seized their chance. Plans were laid for a combined Egyptian and Syrian assault to begin on the morning of Sunday 28th July, on the Jewish holiday of Tisha B'Av.

Those plans however quickly went awry. Israeli intelligence had been monitoring the build-up of Arab forces and had clear indications that an attack was imminent. Despite a plea from President Muskie that Israel had to avoid appearing as the aggressor in any new conflict, the Israeli Prime Minister controversially ordered a pre-emptive strike on Arab forces on the afternoon of Saturday 27th, on the Sabbath itself. Arab forces behind the Suez Canal and Golan Heights took a severe beating, although their state-of-the-art surface-to-air missiles exacted a steep price on Israeli aircraft and pilots.

With war declared for them, the Egyptian and Syrian armies threw themselves across the border on the morning of 28th, but met with stiff resistance from the well prepared Israeli defenders. Despite achieving several local victories through shear weight of numbers, in particular in the vast empty spaces of the Sinai, by Monday it seemed the tide was turning decisively against them, and over the next few days Arab forces were repeatedly mauled by their opponents. Despite the brutal aerial and artillery bombardment suffered by several of her cities, Israeli victory was soon assured. Ten days after Israel’s first strike, Damascus and Cairo surrendered.

Israeli victory however came with a high price. Thousands of Israeli soldiers and civilians had been killed, and over ten-thousand were dead on the Arab side. Israel consolidated and extended its security buffer in southern Syria and the Sinai (incidentally ensuring that the Suez canal remained closed), but faced condemnation from many Second World and non-aligned nations over their pre-emptive strike. The Western Allies generally stood behind Israel, but the weak response of many Western leaders, either in support or condemnation of Israel’s actions, led to political repercussions across the Free World. Finally, the defeated Arab nations took revenge by organising an oil embargo which acted as a hammer-blow to the world’s economy.

But yeah, it's one reason I try and temper my enthusiasm for, say, SpaceX.