Sorry it's a bit later than usual, but here at last is...

Part III Post #6: Yes, But What’s it For?

The history of the Dynasoar Orbital Laboratory, much like the rest of the Dynasoar programme, is one of a solution looking for a question. Originally envisioned as a platform for medium-term (on the order of 1-2 months) manned military observation missions, this role was being brought into question even before the Thebe-DEL DS-9 mission highlighted the limitations of this approach. By 1967, the focus of the mission had changed to a long-duration technology and scientific research facility, with the objective of developing the capability to support long-duration manned flights and investigate the military missions that such a capability would permit. In other words, the mission of DOS became to discover what the mission of DOS was.

This lack of focus was not lost on the Congress, nor on the Nixon or Muskie administrations, but the project stumbled on partly through the lobbying of the aerospace contractors involved, partly to avoid a the development of a capability-gap with the Soviets (who were known to be working on a similar space platform themselves), and partly through sheer inertia. Though funding was gradually restricted as the 1960s headed for their close, there was never quite enough at stake to justify cancellation of the whole project, although the original six missions planned (with a new DOS station per mission) were reduced to just two.

One advantage of the change in DOS’ mission was a switch from the polar orbit favoured for military reconnaissance missions to a lower-inclination orbit, based on a launch from Cape Canaveral. This change, confirmed by Air Force officials in July 1968, allowed almost two tonnes of additional performance to be wrung out of the Minerva-24 launch vehicle, immediately easing the weight-growth problems that had plagued the programme. This was not enough to permit the original concept of launching a crewed Dynasoar on the same vehicle as the DOS to be reinstated, but it did mean that the risky and expensive option of launching the station partly empty and having the first crew ferry up experiments in their Mission Module could be rejected in favour of fully fitting out DOS on the ground. Any lingering concerns over the ability of Dynasoar to rendezvous and dock with the unmanned station were alleviated following

Rhene’s successful link-up with a target vehicle on mission DS-10 in July 1968, and Air Force planners were keen to take advantage of this approach to allow multiple flights to each DOS rather than dispose of the station after a single mission.

The first DOS station, now re-named “Starlab”, finally made it to the launch pad at Cape Canaveral in October 1970. The mission would be the fifth flight of the Minerva-24 configuration, but the first from the Cape, with the four earlier missions having been NRO launches from Vandenberg, all of which had been successful. This impressive reliability record was maintained when the Starlab-1 launch lifted from the pad on the morning of 8th October to place the 19.5 tonne space station into a 452 x 458 km, 28.5 degree orbit about the Earth.

Following the launch, Mission Control at Vandenberg began activating the station and checking that it had survived the launch in a healthy state. Although most readings at first appeared to be nominal, telemetry showed an unexpectedly low power reading from one of the two solar panels. It was soon determined that the panel had failed to deploy fully, cutting its effectiveness by a third. A number of efforts were made to free the panel remotely, first by rolling the station to combine thermal cycling with a mild centrifugal pull, then by “hammering” the station with brief pulses from the attitude control jets, but neither attempt was successful. As the overall power loss (around 20% of total generating capacity) was within acceptable margins, and considering all other systems appeared to be operating nominally, it was decided to go ahead with the Starlab-2 mission and have Dave Merricks and his crew perform a visual inspection and, if feasible, a spacewalk to straighten out the panel. The Mk.II glider

Athena was therefore rolled out to the pad atop her Minerva-22 launcher two weeks after the Starlab launch in preparation for the mission.

Athena’s launch on 20th October went off without a hitch, and Merricks, McEnnis and rookie astronaut Martin Quinn settled in for what was expected to be a two-day flight to rendezvous with the space station. This portion of the flight was made more uncomfortable by the fact that the Starlab-2 Mission Module was packed with additional supplies, rendezvous and docking instruments, and extra fuel for the MM’s power system to support

Athena’s planned four-week stay on-orbit. This meant that the three crewmen were more or less restricted to the main cabin of the Dynasoar glider (though, thankfully, access to the Mission Module’s toilet facilities remained possible). Fortunately, guided by the global tracking stations and ground support available to the Air Force, the rendezvous manoeuvres all went as planned, and on 22nd October

Athena had crept to within a kilometre of the Starlab station. At this point Merricks performed a fly-around of the station, whilst McEnnis and Quinn trained binoculars and cameras on the station, relaying their observations back to Vandenberg and the waiting experts.

The images sent back quickly confirmed that the starboard solar array had failed to fully deploy. Although the quality of the TV images wasn’t clear enough to confirm the cause, the astronauts reported seeing some twisting in the struts of the deployment mechanism, and it was presumably this that had caused the jam. After assessing these initial observations and consulting with the Starlab-2 crew, the Air Force experts agreed with the representatives from Douglass that there was nothing visible that would cause a mission abort, and

Athena was given permission to attempt a docking. Guided by Starlab’s beacon, radar measurements and a black-and-white video camera at the rear of the Mission Module, Merricks gently backed

Athena towards the station at a final closing velocity of under 1 m/s, gently nudging

Athena’s probe into Starlab’s drogue receptacle for a textbook docking.

Following docking, the crew quickly relocated to Starlab’s spacious interior and began making themselves at home. The first three days were spent unpacking

Athena’s Mission Module and powering-up the stations systems, following a new procedure telexed up by Vandenberg to take into account the reduced power supply. There was one brief scare when an improperly sequenced start-up caused tripped some fuses, temporarily leaving the interior in darkness, but this was quickly resolved with no permanent damage done. The lack of power did mean that some of the more energy-intensive experiments that had been planned were abandoned, but for the crew the biggest disappointment was that the microwave oven intended to provide them with hot meals had to be left off, as did the water heater for the collapsible shower unit. Whilst not a serious concern in terms of crew health, it did impact morale. Despite the crew’s recommendation that McEnnis should use a pre-planned EVE on the second week to try to free up the stuck array and restore full power, Vandenberg Control rejected the proposal over concerns that the array could give McEnnis a shock and damage his suit.

Over their four week stay, the Starlab-2 crew gained a lot of insight into how to live in space for extended periods, but the science and military output of the mission was relatively minor. Earth observation results from the two manned telescopes and from automated systems were only slight improvements over those obtained on DEL missions, confirming the limitations that had been previously noted. The space environment measurements and solar UV observations added more data points to results obtained from NEESA’s orbiting observatories, but broke little new ground. When Merricks, McEnnis and Quinn returned to Earth after twenty-seven days on-orbit - a new record - they brought back a wealth of knowledge about the effects of zero gravity on the human body and about operating and maintaining a manned platform over longer term missions, but nothing that fundamentally altered the debates over manned spaceflight.

This experience was soon to be mirrored by the Soviets, with March 1971 finally seeing the launch of the Chasovoy-1 space station. Although officially a continuation of Chelomei’s Almaz station, under Mishin the Chasovoy had undergone an almost complete redesign, with almost all of the internal systems developed from scratch. The 17 tonne station was packed with a host of remote sensing equipment, including a large optical telescope that would out-class anything that had been carried on a Raketoplan mission, as well as a number of experiments designed to take advantage of Chasovoy’s long duration on orbit to space-soak new materials and instruments. Launched into a 230 km, 51.6 degree orbit by a Proton launcher, remote checks from Podlipki confirmed the station was operating correctly, with none of the deployment problems that had troubled the American station.

With Chasovoy safely in orbit, on 22nd March cosmonauts Gagarin and Leonov launched in their Zarya-10 capsule to join the space station. This was only the second spaceflight for the “Second Man in Space” (as the American press still insisted on labelling Gagarin - to the Soviets he was “The First Man in Orbit”), whilst his nominal subordinate, Leonov, was making his third flight. Despite Leonov’s greater experience, there was no way that the Soviet leadership was going to demote Gagarin to second place, but fortunately the good nature and personal warmth shared by both cosmonauts made this a non-issue for the mission.

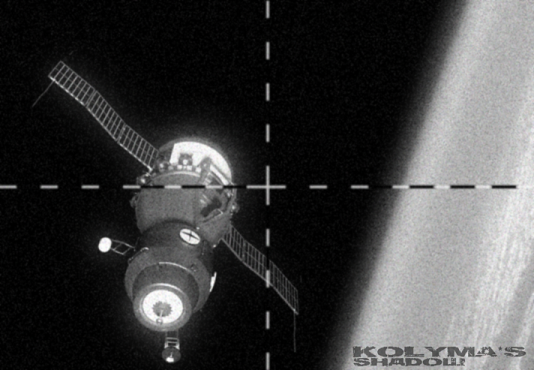

Cosmonauts Gagarin and Leonov approach the Chasovoy-1 space station in their Zarya-10 spaceship, 25th March 1971.

After three days chasing down their target, Zarya-10 finally docked with Chasovoy-1 on 25th March. Upon opening the hatch the cosmonauts found everything more or less in order, although the air smelled “a little stale” according to Leonov. Checks soon confirmed that nothing major was amiss though, and the pair settled down to four weeks of experiments in the new space station. Almost all of these experiments remained top secret, but broadly they mirrored the type of reconnaissance attempts that the Americans had been making with DEL and DOS, with broadly similar results. Although Soviet photoreconnaissance satellites remained inferior to those of the United States, it seemed they were still sufficiently advanced to negate any significant benefits from a manned system. More significant scientific results came from the studies of Gagarin’s and Leonov’s biological reactions to their month-long stay in the roomy station, with the most unexpected result being that Gagarin, finding himself with more room to move around than had been the case on Zarya-1, had suffered from space sickness during his first day in Zarya-10. He quickly recovered and suffered no further problems, but the fact that it had happened at all was a huge surprise to those few doctors who were permitted access to the records - records wrapped in at least as much secrecy as the military experiments.

In total Gagarin and Leonov spent thirty days aboard Chasovoy-1, a duration largely set by Mishin’s desire to beat the American record with Starlab. Gagarin and Leonov both conducted spacewalks in that time, exiting the complex via the Zarya-B orbital module’s side hatch, which eliminated the need for a separate airlock on the station itself. Over the period of their stay on the station, the mission remained routine, but problems were encountered when it came time to return to Earth.

Zarya-B had been designed as an evolution of the basic Zarya design to allow Mishin to quickly expand his manned spaceflight capability and so demonstrate the Soviet lead over the US and his lead over Chelomei. Since its first manned flight in 1964 it had seen some incremental improvements, mostly centred around its adaptable orbital module, but no fundamental redesign. Originally intended for independent missions of up to a week in duration, there had been changes for the Chasovoy project to provide for a month-long “hibernation” period whilst docked to the station, with the updated craft dubbed “Zarya-BM” (with the M standing for “Modifitsirovannyi”, or “Modified”). However, when Gagarin and Leonov came to reactivate their craft they found that these changes had not been quite thorough enough. Tests before undocking with the station revealed that some of the small attitude control thrusters, needed to position the craft for its de-orbit burn, were no longer functioning. Though facing a potentially life-threatening situation, the two veteran cosmonauts calmly reported their situation to ground control and remained docked at Chasovoy awaiting instructions.

At Podlipki, Mikhail Tikhonravov, Zarya’s chief designer, quickly came to the conclusion that some of the spacecraft’s hydrazine propellant may have frozen in the feed pipes during the long stay at the station. He instructed the crew to use Chasovoy’s thrusters to expose previously shadowed areas of Zarya to direct sunlight, which would hopefully unblock the lines. This was done, and after three more orbits Gagarin reported that Zarya’s thrusters were responding normally. To the relief of all involved, Zarya-10 proceeded to undock from the station and went on to conduct a nominal reentry and landing.

Despite their different challenges and divergent heritages, the first Starlab and Chasovoy missions had broadly similar aims and returned similar results. Both were impressive technical feats and proved to demonstrate their owners’ ability to stay in space over increasingly long periods of time, but both had difficulty in answering questions as to their ultimate purpose. Starlab and Chasovoy had demonstrated

how people could operate a space station, but were no closer to answering the question of

why they should do so.

And these aren't ad hoc, hastily thrown together schemes but the evolutionary outcome of previous work that just happens to ripen in time to pave the way for Columbia.

And these aren't ad hoc, hastily thrown together schemes but the evolutionary outcome of previous work that just happens to ripen in time to pave the way for Columbia.