You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

These United States: the Story of Two Congresses

- Thread starter President Benedict Arnold

- Start date

Interlude I: Division of the Northwest Territory and the First Look Around the World

Fitting in with their vision of a small government by and for the people, the Confederationists decided to split up the Northwest Territory. The Northwest Territory was everything the United States had claims on northwest of the Ohio River. While that entire territory was one under the Federalists, the Confederationists decided that it fit their political philosophy more if they divided it up into many different territories that were of the proper size to become states. They also thought that would be better than having somebody appointed by the Federalists report to them, they simply sent him a letter stating that his territory was to be divided up, and thus his command of it was relieved.

The territories that the Northwest Territory was split into are Alleghany, Columbia, Ohio, Michigan, West Michigan, North Mississippi, and Milwaukee. A similar situation developed for the Southwestern Territory which was split into Tennessee, Alabama, West Florida, and South Mississippi.

The Confederationists decided to formulate a law stating that no state shall be added into the United States at a time of national war due to the concentration needed for the task at hand. Kentucky, Maine, and Tennessee, and Alleghany all had applications for statehood waiting in Federal Hall in New York City.

Looking around, the biggest events going on throughout the Atlantic Ocean is the French Revolution and the repercussions of the French-American Alliance. Spain has changed sides, joining France in its war against the First Coalition, and maintained the cordial relations with the United States. The Barbary War, where the United States was hostile to the Ottoman Empire’s North African vassal states over piracy, ended with the signing of the alliance, fearing a major French invasion.

French General and rising star, Napoleon Bonaparte was wrapping up his campaign in Italy, which had been a resounding success, and was getting his plans to invade Ireland and liberate it from British rule. While the Directory was trying to encourage Bonaparte to go to Egypt, American military planners opposed this as a waste of time, seeing the French-American Alliance as an anti-British union first and foremost. The Directory came to agree with Napoleon and the Americans, plotting a large invasion of Ireland. They were in contact with Theobald Wolfe Tone, the leader of the ongoing Irish Rebellion, and plans on creating a community of revolutionary republics began to emerge.

Robert Fulton, an American inventor living in Paris, was hired on by the French Directory at the encouragement of the American diplomat to France. France hired him on to begin construction of an incredibly advanced fleet of we know today as steamship boats. It would be an incredibly expensive project that was not funded enough throughout the Director’s entire existence.

In the Caribbean, after years of unrest the French colony of Saint-Domingue was now under the rule of Governor-General Toussaint Louverture, a former house slave. Louverture was loyal to the French Republic and, with tentative American and Spanish support, was able to maintain control over the French half of the island of Hispaniola.

To many around the world, it seemed as though the old order of Europe would be completely and utterly destroyed with a new order, lead by revolutionary republics, taking its place. At this very moment being an aristocrat seemed as though it would be a death sentence across Europe and America, with many of the wealthiest among the Americans fleeing to Spanish America or Britain in fear of a coming French Revolution-like lashing out against the American equivalent of a nobility lead by Thomas Jefferson. These fears would never come to fruition, but they sure did exist.

Fitting in with their vision of a small government by and for the people, the Confederationists decided to split up the Northwest Territory. The Northwest Territory was everything the United States had claims on northwest of the Ohio River. While that entire territory was one under the Federalists, the Confederationists decided that it fit their political philosophy more if they divided it up into many different territories that were of the proper size to become states. They also thought that would be better than having somebody appointed by the Federalists report to them, they simply sent him a letter stating that his territory was to be divided up, and thus his command of it was relieved.

The territories that the Northwest Territory was split into are Alleghany, Columbia, Ohio, Michigan, West Michigan, North Mississippi, and Milwaukee. A similar situation developed for the Southwestern Territory which was split into Tennessee, Alabama, West Florida, and South Mississippi.

The Confederationists decided to formulate a law stating that no state shall be added into the United States at a time of national war due to the concentration needed for the task at hand. Kentucky, Maine, and Tennessee, and Alleghany all had applications for statehood waiting in Federal Hall in New York City.

Looking around, the biggest events going on throughout the Atlantic Ocean is the French Revolution and the repercussions of the French-American Alliance. Spain has changed sides, joining France in its war against the First Coalition, and maintained the cordial relations with the United States. The Barbary War, where the United States was hostile to the Ottoman Empire’s North African vassal states over piracy, ended with the signing of the alliance, fearing a major French invasion.

French General and rising star, Napoleon Bonaparte was wrapping up his campaign in Italy, which had been a resounding success, and was getting his plans to invade Ireland and liberate it from British rule. While the Directory was trying to encourage Bonaparte to go to Egypt, American military planners opposed this as a waste of time, seeing the French-American Alliance as an anti-British union first and foremost. The Directory came to agree with Napoleon and the Americans, plotting a large invasion of Ireland. They were in contact with Theobald Wolfe Tone, the leader of the ongoing Irish Rebellion, and plans on creating a community of revolutionary republics began to emerge.

Robert Fulton, an American inventor living in Paris, was hired on by the French Directory at the encouragement of the American diplomat to France. France hired him on to begin construction of an incredibly advanced fleet of we know today as steamship boats. It would be an incredibly expensive project that was not funded enough throughout the Director’s entire existence.

In the Caribbean, after years of unrest the French colony of Saint-Domingue was now under the rule of Governor-General Toussaint Louverture, a former house slave. Louverture was loyal to the French Republic and, with tentative American and Spanish support, was able to maintain control over the French half of the island of Hispaniola.

To many around the world, it seemed as though the old order of Europe would be completely and utterly destroyed with a new order, lead by revolutionary republics, taking its place. At this very moment being an aristocrat seemed as though it would be a death sentence across Europe and America, with many of the wealthiest among the Americans fleeing to Spanish America or Britain in fear of a coming French Revolution-like lashing out against the American equivalent of a nobility lead by Thomas Jefferson. These fears would never come to fruition, but they sure did exist.

I will certainly post up a map as soon as this war is done. I have it mostly completed but as of right now it would contain spoilers.

Part IX: The Changing Tide

Part IX: The Changing Tide

The Siege of Montreal really condensed everything good and bad about Commander-in-Chief Aaron Burr down to a simple action. His stubborn resolve and tunnel vision-like determination to achieve big goals showed why the American people and President Jefferson liked him. His poor strategy and repeatedly ignoring the advice of his officers and caring little about letters begging for help from other commanders is why the army grew to hate him and what lead to his ultimate downfall. In September of 1797, Aaron Burr had been held up on the southern side of the Saint Lawrence River for quite a while. His forces and the British were entrenched along the coastline with neither being able to take on the other. Burr believed the British to have low moral and would collapse at any time, but the British were far better supplied than his men were and as time went on they received more and more reinforcements while Burr did not. Burr only had 61,000 troops left of the 97,000 he started the invasion with. Constant harassment by British raiders and poor living conditions were tearing his men apart.

The situation was not desperate until the Vermont Front collapsed under British pressure and the state began to be flooded with British soldiers. The British would have an incredibly hard time securing a rural region they were universally despised in, but the damage to Burr’s reputation was intense. He had lost a state to the British by doing seemingly nothing. Knowing that now he had to get involved, Burr decided to head south to Vermont with 23,000 troops, leaving James Wilkinson as the commander of the remaining forces left outside Montreal. Wilkinson was not the most senior commander when Burr left, but was a personal friend of Aaron Burr and seemingly had been given authority for that reason alone. Wilkinson was well known for his political scandals and had grown to be hated by the New Continental Army by the time he was put in charge of it.

Burr marched south with his army, taking an oddly slow amount of time and arriving there in early November. Burr’s forces were undersupplied and had arrived at a Vermont where all order seemed to have collapsed. John Sherbrooke was the commander of the British forces in Vermont, but he had largely lost control after the successful invasion. The supply lines for his forces had been disrupted by Burr’s advancement and his men, who had lived off of strict rations for too long, went about pillaging the countryside as soon as they could. The disorganized state of the British military in Vermont left Burr’s forces confused, having to go town to town to hunt down British soldiers, who were more or less raiders and highwaymen at this point.

As winter set in, Burr’s men were fighting small, disorganized battles against the splintered forces of an enemy that hardly existed. The only real battle that took place was the Battle of Burlington, where Sherbrooke was captured by Burr’s forces, being given safe passage back to Britain after his surrender, and Burr fortified the city so he could have a warm place to live for the winter.

Up north, his men were furious. They hated Wilkinson for being there and they hated Burr for not. Tensions were incredibly high and opposition to Wilkinson was almost becoming absurd. At a certain point, officers that were supposed to be directly under him began to just stop reporting to him and disregard his orders. The other military commanders would hold meetings on strategy going forward without him and in the official meetings that Wilkinson called, they simply said nothing. It seemed as though the command structure of the New Continental Army itself was going to break down until something completely unexpected happened, in December, Dearborn’s forces in the District of Maine finally defeated the British Army there, which had finally been encircled thanks to the rebellious actions of the New Continental Army officers. His men marched into Saint John, New Brunswick where they remained warm for the winter.

Since the war had been seeming to go bad for the past few months, Dearborn’s success propped him as a hero. Overnight, he became a sensation among the American people and several New Continental Army commanders defected to him, joining the Legion of the United States.

President Jefferson, terrified over these defections, decided that he must bring the American people’s attention away from it all by further changing the narrative of what the war was about. He commissioned the Army of American Patriots in the January of his last full year in office, 1799. The Army of American Patriots was to be sent to Europe to fight for freedom and republican government abroad, becoming famous for their actions during the War of Irish Independence.

President Edmund Randolph and the Federalists believed that they had finally spotted the light at the end of the tunnel. The entire decade of the 1790s was disaster after catastrophe after disaster for them, but the failures of the Siege of Montreal and the New Continental Army looked to be just what they were looking for. Randolph endorsed the Army of American Patriots and called upon his own son, Peyton Randolph, to join its ranks as an officer. This was a popular move among Americans, who saw the lack of military experience among most of the post-Washington Federalists as a stain on their record. Public mood in favor of or against the Federalists and Confederationists had become incredibly muddled by this time, in no small part due to the seeming self-interest and incompetence on both sides.

Upon receiving the news of the breakdown of the Invasion of the United States, Britain decided that they needed to send out anybody they could. One of the most notable commanders sent to North America was Arthur Wellesley, who was sent all of the way from India with a large British force. This move was considered incredibly foolish, partially because of how the fleet of ships was swept up by some storm and never found, and because the removal of those 8,000 men is believed to have been what lost the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War for the British. The loss of that war would guarantee the British would never gain hegemony over the entire subcontinent.

The Siege of Montreal really condensed everything good and bad about Commander-in-Chief Aaron Burr down to a simple action. His stubborn resolve and tunnel vision-like determination to achieve big goals showed why the American people and President Jefferson liked him. His poor strategy and repeatedly ignoring the advice of his officers and caring little about letters begging for help from other commanders is why the army grew to hate him and what lead to his ultimate downfall. In September of 1797, Aaron Burr had been held up on the southern side of the Saint Lawrence River for quite a while. His forces and the British were entrenched along the coastline with neither being able to take on the other. Burr believed the British to have low moral and would collapse at any time, but the British were far better supplied than his men were and as time went on they received more and more reinforcements while Burr did not. Burr only had 61,000 troops left of the 97,000 he started the invasion with. Constant harassment by British raiders and poor living conditions were tearing his men apart.

The situation was not desperate until the Vermont Front collapsed under British pressure and the state began to be flooded with British soldiers. The British would have an incredibly hard time securing a rural region they were universally despised in, but the damage to Burr’s reputation was intense. He had lost a state to the British by doing seemingly nothing. Knowing that now he had to get involved, Burr decided to head south to Vermont with 23,000 troops, leaving James Wilkinson as the commander of the remaining forces left outside Montreal. Wilkinson was not the most senior commander when Burr left, but was a personal friend of Aaron Burr and seemingly had been given authority for that reason alone. Wilkinson was well known for his political scandals and had grown to be hated by the New Continental Army by the time he was put in charge of it.

Burr marched south with his army, taking an oddly slow amount of time and arriving there in early November. Burr’s forces were undersupplied and had arrived at a Vermont where all order seemed to have collapsed. John Sherbrooke was the commander of the British forces in Vermont, but he had largely lost control after the successful invasion. The supply lines for his forces had been disrupted by Burr’s advancement and his men, who had lived off of strict rations for too long, went about pillaging the countryside as soon as they could. The disorganized state of the British military in Vermont left Burr’s forces confused, having to go town to town to hunt down British soldiers, who were more or less raiders and highwaymen at this point.

As winter set in, Burr’s men were fighting small, disorganized battles against the splintered forces of an enemy that hardly existed. The only real battle that took place was the Battle of Burlington, where Sherbrooke was captured by Burr’s forces, being given safe passage back to Britain after his surrender, and Burr fortified the city so he could have a warm place to live for the winter.

Up north, his men were furious. They hated Wilkinson for being there and they hated Burr for not. Tensions were incredibly high and opposition to Wilkinson was almost becoming absurd. At a certain point, officers that were supposed to be directly under him began to just stop reporting to him and disregard his orders. The other military commanders would hold meetings on strategy going forward without him and in the official meetings that Wilkinson called, they simply said nothing. It seemed as though the command structure of the New Continental Army itself was going to break down until something completely unexpected happened, in December, Dearborn’s forces in the District of Maine finally defeated the British Army there, which had finally been encircled thanks to the rebellious actions of the New Continental Army officers. His men marched into Saint John, New Brunswick where they remained warm for the winter.

Since the war had been seeming to go bad for the past few months, Dearborn’s success propped him as a hero. Overnight, he became a sensation among the American people and several New Continental Army commanders defected to him, joining the Legion of the United States.

President Jefferson, terrified over these defections, decided that he must bring the American people’s attention away from it all by further changing the narrative of what the war was about. He commissioned the Army of American Patriots in the January of his last full year in office, 1799. The Army of American Patriots was to be sent to Europe to fight for freedom and republican government abroad, becoming famous for their actions during the War of Irish Independence.

President Edmund Randolph and the Federalists believed that they had finally spotted the light at the end of the tunnel. The entire decade of the 1790s was disaster after catastrophe after disaster for them, but the failures of the Siege of Montreal and the New Continental Army looked to be just what they were looking for. Randolph endorsed the Army of American Patriots and called upon his own son, Peyton Randolph, to join its ranks as an officer. This was a popular move among Americans, who saw the lack of military experience among most of the post-Washington Federalists as a stain on their record. Public mood in favor of or against the Federalists and Confederationists had become incredibly muddled by this time, in no small part due to the seeming self-interest and incompetence on both sides.

Upon receiving the news of the breakdown of the Invasion of the United States, Britain decided that they needed to send out anybody they could. One of the most notable commanders sent to North America was Arthur Wellesley, who was sent all of the way from India with a large British force. This move was considered incredibly foolish, partially because of how the fleet of ships was swept up by some storm and never found, and because the removal of those 8,000 men is believed to have been what lost the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War for the British. The loss of that war would guarantee the British would never gain hegemony over the entire subcontinent.

Last edited:

Interlude II: The Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence is full of a novel’s worth of double crosses, intrigue, political alliances, and sheer dumb luck that every secondary school student in Ireland has to spend at least a semester. Lord Edward FitzGerald’s betrayal, the fluke that was the French landing in Youghal, and the important role of the Army of Patriotic Americans are all memorized material for Irish teenagers. Between Wolfe Tone, Peyton Randolph, William Henry Harrison, and Napoleon Bonaparte, there was no shortage of major world players for the following decades in the conflict.

Theobald Wolfe Tone, better known as simply Wolfe Tone, helped secure backing of his rebellion by the French Directory. The Directory, who always wished to be rid of Napoleon Bonaparte, were more than willing to send him to Ireland with an army of 19,000 soldiers once they were convinced that this action was far more important than any adventures in Egypt, at least for the time being. The French Navy, when united in its entirety, was able to stand against the British Royal Fleet and did so at the time of the invasion in August of 1798. The successful landing of the invasion came when the transport ships broke rank and diverged from their original landing site of the area around Cork, which was controlled by the United Irishmen, to Youghal, which had a minor British encampment. Spotting the landing of tens of thousands of French soldiers, the two hundred or so British stationed there immediately surrendered and Bonaparte was able to get his entire army onto Irish soil without a hint of conflict.

Wolf Tone’s forces and Bonaparte’s united to form a roughly 70,000 man strong army. Not being military commanders of any skill, the Irish Revolutionaries really handed off all control to Bonaparte, who engaged the British in battle after battle, getting nearly half the island under United Irish control by that winter. In the spring of 1799, Bonaparte took off at a sprint as soon as the weather started to lighten up. Dublin was Irish by May. Northern Ireland proved to be far more difficult to take care of. George Warde, the Commander-in-Chief of British Occupied Ireland, had reinforced his armies and was able to fortify the entire region.

It was the surprise arrival of the Army of Patriotic Americans, which landed in Doolin in June 1799, that really changed the game. Roughly 8,000 strong and headed by generally young and relatively inexperienced commanders like Andrew Jackson, William Henry Harrison, and Peyton Randolph, this army, like the Army of the United Irishmen, really just became an extension of Bonaparte’s own army. Jackson, Harrison, and the young Randolph were both incredibly impressed with Bonaparte’s field skills and would learn much from their working under him, essentially becoming his students. It was a Bonaparte-inspired move when Jackson encircled Lieutenant General Gerald Lake’s forces at Kinlough. The greatest American victory in Ireland, often called the Revenge of the Revolution, was when Peyton Randolph lead a battle just south of Assaroe Lake where the Earl Cornwallis was killed. Although Randolph lost that battle, Cornwallis was such a hated figure by Americans during and after the American Revolution, that this was celebrated as a victory back home. President Edmund Randolph’s popularity surged alongside his son’s.

Tragedy struck late in the last stretch of the Irish Campaign in 1801 when Andrew Jackson was assassinated by a British patriot in Strangford. He was taking a break from inspecting the city’s defenses when he was shot twice by a man by the name of Robert Rutherford. Jackson lived for nearly six more hours before dying of his injuries. Rutherford would be arrested and eventually hanged by Harrison for his crime. The young Randolph is quoted to having said about the matter, “America lost a true Patriot today. A true warrior.” In that very city, a statue was erected in Andrew Jackson’s honor, entitled “The American Warrior” less than a decade later.

The Irish War of Independence is full of a novel’s worth of double crosses, intrigue, political alliances, and sheer dumb luck that every secondary school student in Ireland has to spend at least a semester. Lord Edward FitzGerald’s betrayal, the fluke that was the French landing in Youghal, and the important role of the Army of Patriotic Americans are all memorized material for Irish teenagers. Between Wolfe Tone, Peyton Randolph, William Henry Harrison, and Napoleon Bonaparte, there was no shortage of major world players for the following decades in the conflict.

Theobald Wolfe Tone, better known as simply Wolfe Tone, helped secure backing of his rebellion by the French Directory. The Directory, who always wished to be rid of Napoleon Bonaparte, were more than willing to send him to Ireland with an army of 19,000 soldiers once they were convinced that this action was far more important than any adventures in Egypt, at least for the time being. The French Navy, when united in its entirety, was able to stand against the British Royal Fleet and did so at the time of the invasion in August of 1798. The successful landing of the invasion came when the transport ships broke rank and diverged from their original landing site of the area around Cork, which was controlled by the United Irishmen, to Youghal, which had a minor British encampment. Spotting the landing of tens of thousands of French soldiers, the two hundred or so British stationed there immediately surrendered and Bonaparte was able to get his entire army onto Irish soil without a hint of conflict.

Wolf Tone’s forces and Bonaparte’s united to form a roughly 70,000 man strong army. Not being military commanders of any skill, the Irish Revolutionaries really handed off all control to Bonaparte, who engaged the British in battle after battle, getting nearly half the island under United Irish control by that winter. In the spring of 1799, Bonaparte took off at a sprint as soon as the weather started to lighten up. Dublin was Irish by May. Northern Ireland proved to be far more difficult to take care of. George Warde, the Commander-in-Chief of British Occupied Ireland, had reinforced his armies and was able to fortify the entire region.

It was the surprise arrival of the Army of Patriotic Americans, which landed in Doolin in June 1799, that really changed the game. Roughly 8,000 strong and headed by generally young and relatively inexperienced commanders like Andrew Jackson, William Henry Harrison, and Peyton Randolph, this army, like the Army of the United Irishmen, really just became an extension of Bonaparte’s own army. Jackson, Harrison, and the young Randolph were both incredibly impressed with Bonaparte’s field skills and would learn much from their working under him, essentially becoming his students. It was a Bonaparte-inspired move when Jackson encircled Lieutenant General Gerald Lake’s forces at Kinlough. The greatest American victory in Ireland, often called the Revenge of the Revolution, was when Peyton Randolph lead a battle just south of Assaroe Lake where the Earl Cornwallis was killed. Although Randolph lost that battle, Cornwallis was such a hated figure by Americans during and after the American Revolution, that this was celebrated as a victory back home. President Edmund Randolph’s popularity surged alongside his son’s.

Tragedy struck late in the last stretch of the Irish Campaign in 1801 when Andrew Jackson was assassinated by a British patriot in Strangford. He was taking a break from inspecting the city’s defenses when he was shot twice by a man by the name of Robert Rutherford. Jackson lived for nearly six more hours before dying of his injuries. Rutherford would be arrested and eventually hanged by Harrison for his crime. The young Randolph is quoted to having said about the matter, “America lost a true Patriot today. A true warrior.” In that very city, a statue was erected in Andrew Jackson’s honor, entitled “The American Warrior” less than a decade later.

This is a major update so I hope you enjoy. The map at the end is kind of hideous but I could not get it to look any better than I did.

Part X: The Fall of Aaron Burr and the Rise of Dearborn

Part X: The Fall of Aaron Burr and the Rise of Dearborn

In March of 1799, Aaron Burr’s popularity among the general public began to really take a hit. Burr’s popularity really came from the popularity of the Confederation and the importance they bestowed upon him. Now that Jefferson saw the error of tying the idea of the Confederation Congress on Aaron Burr’s military success, the entirety of the Confederation wished to distance itself from him. Burr was still unable to secure Vermont, where British soldiers, far from home and with no supply lands, were now nothing but well armed and well trained bandits. The people of Vermont hated Burr. He and his entourage of soldiers were often pelted with rotting food as they walked through the streets of Burlington, mocking the common practice of raiding for supplies.

Burr had to know that the writing was on the wall but it wasn’t until he received word that Wilkinson had been arrested by the very men he had been put in charge of that he knew that he was finished. What remained of the new Continental Army that resided in British North America defected to the Legion of the United States. This, along with major recruitment drives across Constitutional and Confederation states, brought the numbers of the Legion from about 5,000 at the beginning of the war to roughly 64,000, with plenty of reinforcements on the way. Dearborn, the commander of the Legion, made smart opening moves as he furthered his campaign into the Canadas. His troops moved to secure Nova Scotia, and from there Prince Edward Island, taking away a major British port and crippling the Transatlantic capabilities of the British Fleet.

By July of 1799, Dearborn was successfully marching on Quebec City, where order had broken down between those who were beginning to support the idea of self-governance and Republicanism coming to their city and the vast majority of its residence. Dearborn’s forces were unable to take the city however, and the pro-Republican riots really only served to discredit the idea of American democracy coming there. About 1,200 men and women abandoned the city and joined Dearborn’s camp. Sadly, they had no vital siege information to give and in September Dearborn abandoned the siege to continue securing territory. This move was pointed out as an example of weakness by Aaron Burr, who was now only nominally in control of the nearly 20,000 men he had in Vermont, but the public disagreed. They were sick of lengthy sieges that brought the country and the war nowhere.

Burr finally resigned his position on October 16th, 1799, supposedly due to pressure from Jefferson, but there is no known evidence of this. The Confederation Congress, seemingly in a desperate attempt to save face, decided to vote for Henry Dearborn as the new Commander-in-Chief and leader of the new Continental Army. Dearborn supposedly denied this “honor” and continued on as the commander of the Legion of the United States. Despite this, the Confederation Congress would send provisions explicitly sent for the Continental Army. Dearborn had his men cover that up with paint and use the provisions anyway.

President Jefferson of the Confederation Congress was re-elected as President of the Confederation, despite making no overt moves towards winning it. He seemed very reluctant at his post and, according to some records, regarded his first term as such a failure that it really was not worth it to run for a second one to him. The Confederation Congress as a whole was doing terribly. The states that had applied for statehood with them had since withdrawn their applications. They had not yet applied to be part of the Constitutional Congress but the writing was on the wall.

It took until November of 1801 for the war to finally finish. Although the Americans never successfully sieged Montreal or Quebec, they controlled most of the rest of mainland British North America with no real British challenge. The British could do little in Ireland as well, with very competent defenses set up in Ulster against an invasion from Scotland. Sir Robert Milnes, who had been a prisoner of Dearborn’s since June of 1800, was the chief representative of Britain walking into the Hartford Talks on peace. What became known as the Republican Coalition, that being the United States, the French Republic, the Irish Republic, and the Kingdoms of Spain, walked into the peace talks with only absolute victory in Ireland and Germany. Everywhere else was heavily leaning towards them and had been for an entire year. President Edmund Randolph, easily winning his second term, wanted his son at the negotiating table. According to the journals of two other diplomats, Peyton Randolph, despite his success as a lawyer and a military commander, was an absolutely terrible diplomat. They claimed that there was a deal being negotiated where Britain would secede all of mainland British North America, only keeping Prince Edward Island, Cape Breton Island, Newfoundland, and the smaller surrounding islands under their control. This is widely disputed by historians who claim that treaty talks are far closer to lawyer work than most other activities Peyton Randolph demonstrated success at. There is also evidence to suggest a mutual personal dislike between the young Randolph and these other diplomats.

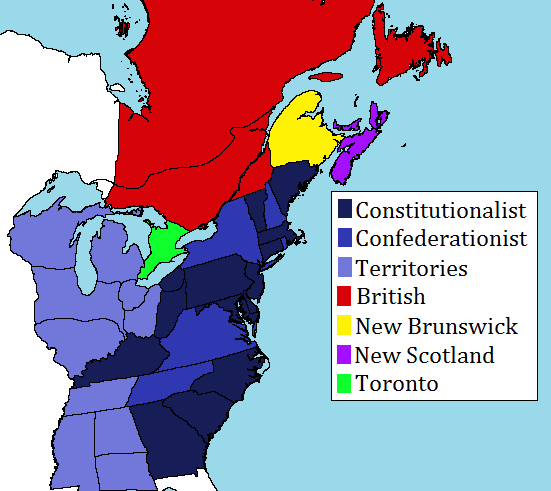

Whether or not these statements were truthful, the Treaty of Hartford that did not determine the outcome of the war, as many Americans are falsely taught, but the future of British North America was signed with the following provisions. Firstly, British North America was to end at Sault Sainte Marie, which connected Lake Superior to the North Channel and Lake Huron. Secondly, Britain was to release several border territories of the United States as independent republics, these being the Republic of Toronto, the Republic of New Brunswick, and the Republic of New Scotland. Thirdly, the British must end the impressment of American sailors. This treaty was massively popular and the months following it saw the Constitutional government absolutely come dominate the politics of the United States. Kentucky, Alleghany, Maine, and Tennessee are added as states to the United States as Constitutional states. The independent republics that were just taken from Britain are being organized into functional republican governments with the goal of annexing them within the next decade. The biggest blows against the Confederationists came one right after the other. One July 3rd of 1801, Vermont ratified the Constitution and joined the Constitutional Congress to help alleviate the damage that had been done during the war. They did this under the sole condition that Aaron Burr be arrested and charged for his crimes. He would be tried before the Supreme Court and eventually exiled from the United States. Upon his arrest, Thomas Jefferson resigned in disgrace and returned to his home estate. The Confederationists went from the top of the world to looking like they were about to no longer exist within only a couple of years. It was under these conditions that George Clinton was sworn in as president by the Confederation Congress and it was under these conditions that the first decade of the Nineteenth Century would be known as the Decade of Reform.

In the Grand Peace Treaty signing in France, tensions were very high. Edmund Randolph, now the recognized head of state for the United States, had politically opposed the alliance with Spain and France at all, but his subordinates had won the war and seemed to have little interest in forcing them off of the continent of North America, resulting in tentative relations being established. France and the United States reaffirmed their alliance at this peace conference while Spain decided not to. The United States and France both promised to protect the new Irish Republic, along with the Helvetic Republic, the Batavian Republic, the Rhine Republic, and the Italian Republic, which all of the signees had to formally recognize as an independent state. This peace also formalized what was now officially being called the Republican Coalition, with France and the United States being its distinguished leaders.

State of affairs in North America:

In March of 1799, Aaron Burr’s popularity among the general public began to really take a hit. Burr’s popularity really came from the popularity of the Confederation and the importance they bestowed upon him. Now that Jefferson saw the error of tying the idea of the Confederation Congress on Aaron Burr’s military success, the entirety of the Confederation wished to distance itself from him. Burr was still unable to secure Vermont, where British soldiers, far from home and with no supply lands, were now nothing but well armed and well trained bandits. The people of Vermont hated Burr. He and his entourage of soldiers were often pelted with rotting food as they walked through the streets of Burlington, mocking the common practice of raiding for supplies.

Burr had to know that the writing was on the wall but it wasn’t until he received word that Wilkinson had been arrested by the very men he had been put in charge of that he knew that he was finished. What remained of the new Continental Army that resided in British North America defected to the Legion of the United States. This, along with major recruitment drives across Constitutional and Confederation states, brought the numbers of the Legion from about 5,000 at the beginning of the war to roughly 64,000, with plenty of reinforcements on the way. Dearborn, the commander of the Legion, made smart opening moves as he furthered his campaign into the Canadas. His troops moved to secure Nova Scotia, and from there Prince Edward Island, taking away a major British port and crippling the Transatlantic capabilities of the British Fleet.

By July of 1799, Dearborn was successfully marching on Quebec City, where order had broken down between those who were beginning to support the idea of self-governance and Republicanism coming to their city and the vast majority of its residence. Dearborn’s forces were unable to take the city however, and the pro-Republican riots really only served to discredit the idea of American democracy coming there. About 1,200 men and women abandoned the city and joined Dearborn’s camp. Sadly, they had no vital siege information to give and in September Dearborn abandoned the siege to continue securing territory. This move was pointed out as an example of weakness by Aaron Burr, who was now only nominally in control of the nearly 20,000 men he had in Vermont, but the public disagreed. They were sick of lengthy sieges that brought the country and the war nowhere.

Burr finally resigned his position on October 16th, 1799, supposedly due to pressure from Jefferson, but there is no known evidence of this. The Confederation Congress, seemingly in a desperate attempt to save face, decided to vote for Henry Dearborn as the new Commander-in-Chief and leader of the new Continental Army. Dearborn supposedly denied this “honor” and continued on as the commander of the Legion of the United States. Despite this, the Confederation Congress would send provisions explicitly sent for the Continental Army. Dearborn had his men cover that up with paint and use the provisions anyway.

President Jefferson of the Confederation Congress was re-elected as President of the Confederation, despite making no overt moves towards winning it. He seemed very reluctant at his post and, according to some records, regarded his first term as such a failure that it really was not worth it to run for a second one to him. The Confederation Congress as a whole was doing terribly. The states that had applied for statehood with them had since withdrawn their applications. They had not yet applied to be part of the Constitutional Congress but the writing was on the wall.

It took until November of 1801 for the war to finally finish. Although the Americans never successfully sieged Montreal or Quebec, they controlled most of the rest of mainland British North America with no real British challenge. The British could do little in Ireland as well, with very competent defenses set up in Ulster against an invasion from Scotland. Sir Robert Milnes, who had been a prisoner of Dearborn’s since June of 1800, was the chief representative of Britain walking into the Hartford Talks on peace. What became known as the Republican Coalition, that being the United States, the French Republic, the Irish Republic, and the Kingdoms of Spain, walked into the peace talks with only absolute victory in Ireland and Germany. Everywhere else was heavily leaning towards them and had been for an entire year. President Edmund Randolph, easily winning his second term, wanted his son at the negotiating table. According to the journals of two other diplomats, Peyton Randolph, despite his success as a lawyer and a military commander, was an absolutely terrible diplomat. They claimed that there was a deal being negotiated where Britain would secede all of mainland British North America, only keeping Prince Edward Island, Cape Breton Island, Newfoundland, and the smaller surrounding islands under their control. This is widely disputed by historians who claim that treaty talks are far closer to lawyer work than most other activities Peyton Randolph demonstrated success at. There is also evidence to suggest a mutual personal dislike between the young Randolph and these other diplomats.

Whether or not these statements were truthful, the Treaty of Hartford that did not determine the outcome of the war, as many Americans are falsely taught, but the future of British North America was signed with the following provisions. Firstly, British North America was to end at Sault Sainte Marie, which connected Lake Superior to the North Channel and Lake Huron. Secondly, Britain was to release several border territories of the United States as independent republics, these being the Republic of Toronto, the Republic of New Brunswick, and the Republic of New Scotland. Thirdly, the British must end the impressment of American sailors. This treaty was massively popular and the months following it saw the Constitutional government absolutely come dominate the politics of the United States. Kentucky, Alleghany, Maine, and Tennessee are added as states to the United States as Constitutional states. The independent republics that were just taken from Britain are being organized into functional republican governments with the goal of annexing them within the next decade. The biggest blows against the Confederationists came one right after the other. One July 3rd of 1801, Vermont ratified the Constitution and joined the Constitutional Congress to help alleviate the damage that had been done during the war. They did this under the sole condition that Aaron Burr be arrested and charged for his crimes. He would be tried before the Supreme Court and eventually exiled from the United States. Upon his arrest, Thomas Jefferson resigned in disgrace and returned to his home estate. The Confederationists went from the top of the world to looking like they were about to no longer exist within only a couple of years. It was under these conditions that George Clinton was sworn in as president by the Confederation Congress and it was under these conditions that the first decade of the Nineteenth Century would be known as the Decade of Reform.

In the Grand Peace Treaty signing in France, tensions were very high. Edmund Randolph, now the recognized head of state for the United States, had politically opposed the alliance with Spain and France at all, but his subordinates had won the war and seemed to have little interest in forcing them off of the continent of North America, resulting in tentative relations being established. France and the United States reaffirmed their alliance at this peace conference while Spain decided not to. The United States and France both promised to protect the new Irish Republic, along with the Helvetic Republic, the Batavian Republic, the Rhine Republic, and the Italian Republic, which all of the signees had to formally recognize as an independent state. This peace also formalized what was now officially being called the Republican Coalition, with France and the United States being its distinguished leaders.

State of affairs in North America:

Sorry this took a little while, classes started this week.

Interlude III: The French Civil War

While tensions were high in the United States, and had been high for decades, they were nothing compared to what was about to happen in France. The French Republic was about radical shifts and changes in government. The revolutionary government started with some modest attempts at reforming the Ancien Regime and then eventually killed the royal family, declared itself a republic, and at one point tried to replace Catholicism itself with the Cult of the Supreme Being. This all came to an end in March of 1802, when the War of the First Coalition was officially over. There were two great military leaders that had emerged from France during the war, Napoleon Bonaparte of Corsica and Lazare Hoche of Versailles. While General Bonaparte made his name first in Italy and then Ireland, helping to form both into major republican allies of France. General Hoche made his name in the Vendee and then the Lowlands and Germany, winning some of the greatest victories of the war and being the main force behind the defeat of Austria and Prussia. The Dutch Republic, the Cisrhennian Republic, and the Swabian Republic were also allied republics.

Due to both of them having immense reputations among the French, and seeing the ways that the Directory would not last long, they began to plot. The two of them both agreed that the revolution had run its course and that after the death of such figures as Robespierre, there were few left in politics who were even capable of leading France. They eventually came to agree that they together could overthrow the Directory and begin a new government based around maintaining the progress the revolution made while shedding its instability and consistent bloodshed. The ex-bishop, crafty statesman, smart diplomat, con artist, habitual drinker, and womanizer known as Talleyrand and Napoleon Bonaparte’s brother Lucien both played major roles in the plot. The group conspired to get the entirety of the French Directory government out of the city and to the Chateau of Saint-Cloud. Thousands of French troops who hated these government officials due to delays in their pay were stationed and kept them under heavy guard. Hoche and Bonaparte both declared that the Directory was no longer in power to the Council of Ancients, who mostly stared onto their declaration in silence. They then repeated their statements to the Council of the Five Hundred, with a far more hostile response. They were accused of treason and there were calls for both of them to be executed. They responded by, after being escorted out of the building by guards, sending in soldiers to clear out the council. Most of the Council of Five Hundred was brought back in and voted in favor of abolishing the current French Constitution and replacing it with a new one where there would be two Consuls ruling France, Bonaparte and Hoche. This was the end of the French Directory.

It only took a few months of working together as co-dictators for Hoche and Bonaparte to find each other insufferable. Hoche saw Bonaparte as overly self-interested with too big of an ego and not a true believer in the goals of the revolution. Bonaparte saw Hoche’s input and ideological tenets as limiting and in the way of his goals. The two were destined to face off on every disagreement until one or the other finally gave in. Despite the growing rivalry in the French government, the entirety of Europe finally had a few years of peace. The French were a hegemonic power over the entire continent and the rule of two brought about some major restrictions to the other countries, including the Continental System. The Continental System was a system where all goods coming into Europe had to be marked by their country of origin and British goods were given a strong tax at every check. Depending on the country, a crate of goods could be checked as many as four or five times before reaching its ultimate destination, making British goods unaffordable compared to all others. This, paired with the results of the Irish Revolution, brought about a massive depression in the British economy, which lasted until 1811, when they signed a treaty with France that split the continent of Australia and the subcontinent of India in half between them in exchange for a lightening of the Continental System’s taxes. The crippled empire would stay out of all European wars until then.

In April 1805, Hoche and Bonaparte’s common disagreements reached a boiling point over the re-institution of Catholicism. Bonaparte, being much more conservative than Hoche, believed that Catholicism should be re-instated as the state religion of France. Hoche believed in freedom of religion and, while he wanted to remove the stigma against Catholicism that had grown among political circles, he did not want it to return to an official role in the French government. The conflict quickly got out of hand when Bonaparte decided to just go through with his plan while ignoring Hoche’s opposition. He met with Pope Pius VII and decided that he was going to hand over much of the Republic of Italy’s territory back to the Papacy. The Papal States were at that point only limited to the city of Rome, some surrounding farmlands, and several cathedrals and monasteries throughout the northern half of the Italian Peninsula. Consul Hoche declared this move illegal, because it had not been agreed upon. Bonaparte, meeting with Papal representatives in Avignon, where the Papacy had been located for nearly seventy years centuries ago, was formalizing these plans when Hoche decided to march upon the city with an army. Hoche could not allow Bonaparte to undermine his position, fearing death or arrest at Bonaparte’s hands if he were to gain dominance politically.

Avignon was sieged for a period of three months before Napoleon, his close allies, and the Papal diplomats managed to escape in the shadow of night. The Pope’s representatives fled back to Italy while Bonaparte went north to gather an army. The French Civil War had begun. The war would mostly be fought in eastern France, mainly near the Helvetic Republic. Various commanders and sister republics supported one side or the other during the conflict. The United States and the Helvetic Republic remained neutral, but the Italian Republic and Irish Republic supported Napoleon Bonaparte while the Dutch Republic, the Cisrhennian Republic, and the Swabian Republic supported Lazare Hoche. On June 19th, 1807, just three miles north of the city of Dijon, Napoleon Bonaparte supposedly had a secret meeting with close political allies. He apparently revealed his plans for once Hoche was dead: he wanted to march into Paris and declare himself Emperor of the French. Historians dispute this as a fabrication by soldiers who simply opposed Napoleon, finding nothing varifiable of Napoleon Bonaparte every seeking to become an emperor. Two of his soldiers claimed to have overheard this and, telling four more men, began to plot to kill Consul Bonaparte before he could become a monarch. One of the men backed out and, a little too late, would report this to a superior officer. The remaining five men would follow through with the plan only hours after they began to plot. Three men loaded up rifles and positioned themselves near the entrance to Napoleon’s tent. When he emerged, they fired upon him. Two of them hit him, one in the right shoulder and the other in the left thigh. Falling to the ground in agony, he was unable to defend himself as the remaining two plotters ran up with knives and stabbed him repeatedly. One of these men, named Louis, supposedly shouted “Sic semper tyrannis!” before slicing Consul Bonaparte’s throat. The five men made no attempt to prevent their arrest and were hanged for the assassination that night. It did not matter much either way, Lazare Hoche had won.

Consul Lazare Hoche did not treat this as a triumph, at least not outwardly. He reportedly wept at the news of Napoleon’s assassination, although this is likely a fabrication to gain the support of those who preferred the late Bonaparte, and held a grand funerary service for him. Consul Hoche was now the sole ruler of France and would diligently spend his time putting out any fires or growing conflicts throughout Europe. He solidified the ideals of the republican government and, over the course of his reign, turned the dictatorship into a republic with a rather strong executive. He would rule France directly and Europe by proximity until his death in 1832, leaving behind a lengthy legacy as a great mediator, healer, and reformer. He would also be one of the people most directly responsible for the Industrial Revolution.

Interlude III: The French Civil War

While tensions were high in the United States, and had been high for decades, they were nothing compared to what was about to happen in France. The French Republic was about radical shifts and changes in government. The revolutionary government started with some modest attempts at reforming the Ancien Regime and then eventually killed the royal family, declared itself a republic, and at one point tried to replace Catholicism itself with the Cult of the Supreme Being. This all came to an end in March of 1802, when the War of the First Coalition was officially over. There were two great military leaders that had emerged from France during the war, Napoleon Bonaparte of Corsica and Lazare Hoche of Versailles. While General Bonaparte made his name first in Italy and then Ireland, helping to form both into major republican allies of France. General Hoche made his name in the Vendee and then the Lowlands and Germany, winning some of the greatest victories of the war and being the main force behind the defeat of Austria and Prussia. The Dutch Republic, the Cisrhennian Republic, and the Swabian Republic were also allied republics.

Due to both of them having immense reputations among the French, and seeing the ways that the Directory would not last long, they began to plot. The two of them both agreed that the revolution had run its course and that after the death of such figures as Robespierre, there were few left in politics who were even capable of leading France. They eventually came to agree that they together could overthrow the Directory and begin a new government based around maintaining the progress the revolution made while shedding its instability and consistent bloodshed. The ex-bishop, crafty statesman, smart diplomat, con artist, habitual drinker, and womanizer known as Talleyrand and Napoleon Bonaparte’s brother Lucien both played major roles in the plot. The group conspired to get the entirety of the French Directory government out of the city and to the Chateau of Saint-Cloud. Thousands of French troops who hated these government officials due to delays in their pay were stationed and kept them under heavy guard. Hoche and Bonaparte both declared that the Directory was no longer in power to the Council of Ancients, who mostly stared onto their declaration in silence. They then repeated their statements to the Council of the Five Hundred, with a far more hostile response. They were accused of treason and there were calls for both of them to be executed. They responded by, after being escorted out of the building by guards, sending in soldiers to clear out the council. Most of the Council of Five Hundred was brought back in and voted in favor of abolishing the current French Constitution and replacing it with a new one where there would be two Consuls ruling France, Bonaparte and Hoche. This was the end of the French Directory.

It only took a few months of working together as co-dictators for Hoche and Bonaparte to find each other insufferable. Hoche saw Bonaparte as overly self-interested with too big of an ego and not a true believer in the goals of the revolution. Bonaparte saw Hoche’s input and ideological tenets as limiting and in the way of his goals. The two were destined to face off on every disagreement until one or the other finally gave in. Despite the growing rivalry in the French government, the entirety of Europe finally had a few years of peace. The French were a hegemonic power over the entire continent and the rule of two brought about some major restrictions to the other countries, including the Continental System. The Continental System was a system where all goods coming into Europe had to be marked by their country of origin and British goods were given a strong tax at every check. Depending on the country, a crate of goods could be checked as many as four or five times before reaching its ultimate destination, making British goods unaffordable compared to all others. This, paired with the results of the Irish Revolution, brought about a massive depression in the British economy, which lasted until 1811, when they signed a treaty with France that split the continent of Australia and the subcontinent of India in half between them in exchange for a lightening of the Continental System’s taxes. The crippled empire would stay out of all European wars until then.

In April 1805, Hoche and Bonaparte’s common disagreements reached a boiling point over the re-institution of Catholicism. Bonaparte, being much more conservative than Hoche, believed that Catholicism should be re-instated as the state religion of France. Hoche believed in freedom of religion and, while he wanted to remove the stigma against Catholicism that had grown among political circles, he did not want it to return to an official role in the French government. The conflict quickly got out of hand when Bonaparte decided to just go through with his plan while ignoring Hoche’s opposition. He met with Pope Pius VII and decided that he was going to hand over much of the Republic of Italy’s territory back to the Papacy. The Papal States were at that point only limited to the city of Rome, some surrounding farmlands, and several cathedrals and monasteries throughout the northern half of the Italian Peninsula. Consul Hoche declared this move illegal, because it had not been agreed upon. Bonaparte, meeting with Papal representatives in Avignon, where the Papacy had been located for nearly seventy years centuries ago, was formalizing these plans when Hoche decided to march upon the city with an army. Hoche could not allow Bonaparte to undermine his position, fearing death or arrest at Bonaparte’s hands if he were to gain dominance politically.

Avignon was sieged for a period of three months before Napoleon, his close allies, and the Papal diplomats managed to escape in the shadow of night. The Pope’s representatives fled back to Italy while Bonaparte went north to gather an army. The French Civil War had begun. The war would mostly be fought in eastern France, mainly near the Helvetic Republic. Various commanders and sister republics supported one side or the other during the conflict. The United States and the Helvetic Republic remained neutral, but the Italian Republic and Irish Republic supported Napoleon Bonaparte while the Dutch Republic, the Cisrhennian Republic, and the Swabian Republic supported Lazare Hoche. On June 19th, 1807, just three miles north of the city of Dijon, Napoleon Bonaparte supposedly had a secret meeting with close political allies. He apparently revealed his plans for once Hoche was dead: he wanted to march into Paris and declare himself Emperor of the French. Historians dispute this as a fabrication by soldiers who simply opposed Napoleon, finding nothing varifiable of Napoleon Bonaparte every seeking to become an emperor. Two of his soldiers claimed to have overheard this and, telling four more men, began to plot to kill Consul Bonaparte before he could become a monarch. One of the men backed out and, a little too late, would report this to a superior officer. The remaining five men would follow through with the plan only hours after they began to plot. Three men loaded up rifles and positioned themselves near the entrance to Napoleon’s tent. When he emerged, they fired upon him. Two of them hit him, one in the right shoulder and the other in the left thigh. Falling to the ground in agony, he was unable to defend himself as the remaining two plotters ran up with knives and stabbed him repeatedly. One of these men, named Louis, supposedly shouted “Sic semper tyrannis!” before slicing Consul Bonaparte’s throat. The five men made no attempt to prevent their arrest and were hanged for the assassination that night. It did not matter much either way, Lazare Hoche had won.

Consul Lazare Hoche did not treat this as a triumph, at least not outwardly. He reportedly wept at the news of Napoleon’s assassination, although this is likely a fabrication to gain the support of those who preferred the late Bonaparte, and held a grand funerary service for him. Consul Hoche was now the sole ruler of France and would diligently spend his time putting out any fires or growing conflicts throughout Europe. He solidified the ideals of the republican government and, over the course of his reign, turned the dictatorship into a republic with a rather strong executive. He would rule France directly and Europe by proximity until his death in 1832, leaving behind a lengthy legacy as a great mediator, healer, and reformer. He would also be one of the people most directly responsible for the Industrial Revolution.

Last edited:

Ok, this is interesting.

Clearly Hoche is more of the republican dictator than revolutionary emperor type that Napoleon was IOTL. I may tone down my earlier post to only burn most of the French.

We need a map of Europe.

Also, how is Austria and the rest of the HRE doing ITTL?

Clearly Hoche is more of the republican dictator than revolutionary emperor type that Napoleon was IOTL. I may tone down my earlier post to only burn most of the French.

We need a map of Europe.

Also, how is Austria and the rest of the HRE doing ITTL?

I'm hoping to have the next actual part out sooner than the last one. I'm not counting interludes as parts, seeing as how they overwhelmingly focus on events outside of the United States and usually don't expand on the story.

As much as I understand the love and desire for maps, I am very poor at making them and would rather only embarrass myself on rare occasions. I will have a map of the entire North Atlantic (Europe and North America) out within the next couple of parts, seeing as how a lot is going to change over that time.

Part XI: The Reluctant Federalists and the Decade of Reform

In early 1802, George Clinton, President of the Confederation, knew that the Confederation had to adapt or die. After the series of failures that brought a resurgence in popularity to the Constitutional government, Clinton foresaw that the Confederation either needed to reform or disband entirely. He called upon the remaining Confederation states to meet in Richmond, Virginia to discuss what to change and how to go about doing it. It was decided that the Articles of Confederation would be replaced with the Second Articles of Confederation. Many notable figures attended this not-exactly convention, including notable Confederationists like Thomas Jefferson, James Monroe, and Samuel Adams, along with the Irish Revolutionary War Heroes William Henry Harrison and Peyton Randolph. Peyton Randolph attended due to him and his father both being Virginia natives, but his father not being able to show up at the convention of a government he considered illegal for obvious reasons. Despite their inexperience in government, Harrison and Randolph had quite a lot of prestige among those who attended the Confederation Convention. With their experiences in Europe with revolutionary ideals in Ireland and France, they had a very different outlook than the Confederationists and the end result really shows.

Over the following years, many ideas emerged from the convention on how to change the articles to better fit what was being demanded of government. An equivalent to the Bill of Rights, called the Declaration of Rights, was one of the first documents to emerge. The Declaration of Rights went further than the Bill of Rights in some ways, including an explicitly stated right to vote for all free men and explicitly prohibiting the revocation of the right to vote for any American citizen who qualifies. There were also limits on government officials, with declarations regarding pay and term limits. Regarding pay, the representatives could raise the pay of the members of the Confederation Congress, but it could not come into effect until the beginning of the term after the next. Regarding term limits, there was a proclamation that each representative was to be limited to four three year terms, with a single three year long break before they can serve four more terms.

These changes were incredibly popular and made the general population question why the Constitution lacked them. Every states of the United States had different rules regarding who qualified to vote and the vast majority of them limited people to only landowners.

The next document that was released by the Confederation Convention came a year and a half later, in November of 1803. It was called the Declaration of the Legislative Branch and formally recognized the authority of the Executive and Judicial Branches of the Constitutional government as fulfilling the same role for the Confederation government. While it acknowledged the existence of the Constitutional Congress, it proclaimed that the Confederation Congress would continue on as its own separate and distinguished legislature. Some hardline Confederationists saw this as an act of surrender but nearly everybody else agreed that it was for the best. Now the Confederation states would be counted as part of the Electoral College and the President of the United States would be the president for the entire United States. This declaration also changed the title of the head of the Confederation Congress from president to consul, in reference to the new co-consuls out in France. This titling was considered incredibly controversial, as most Americans saw this move as an unjustified coup, but it passed nonetheless. The position of consul could only be held for one entire term, three years. Somebody could become consul twice, but not in a row and not any number above that. Another provision stated this document stated that any state could leave the Confederation Congress any time they wished, but only by ratifying the Constitution and joining the Constitutional Congress, like what Vermont had done. The Confederation Convention also resolved the matter of the placement of each institution. Believing that too much of a bias would form if they were in the same place, the Confederation only agreed to recognize the authority of the President and the Supreme Court if the President relocated to the City of Philadelphia and the Supreme Court relocated to the City of Richmond. The Constitutional Congress remained in the Federal District, which would soon be renamed the District of Washington in honor of the deceased first president and commander-in-chief.

The last provision is what kept this document from being released at the same time as the Declaration of Rights. Many at the Convention argued against it but in the end Peyton Randolph and William Henry Harrison managed to get it through and had to wait for the Constitutional Congress to do the same. Each state of the Constitutional Congress would have a single representative in the Confederation Congress and each Confederation state would have a single representative and a single senator in the Constitutional Congress. This was to make the two separate legislatures become more integrated while remaining as entirely separate institutions. Although this last bit was not a formal provision, it became the de facto law of the land that Amendments to the Constitution and Declarations of the Articles were on equal terms of political power and that neither applied as overarching laws of the land. The only things that could were Supreme Court rulings where both the Constitution and the Articles were being questioned, which would rarely ever happen.

This was all set in stone by the Presidential Election of 1804. The election would become a landslide victory for Henry Dearborn. Dearborn was the perfect choice by the now formal Federalist Party, headed by Alexander Hamilton who otherwise lived in total obscurity. Going into the election, Dearborn was universally loved as a war hero and liberator. The Federalists supported his service under the Constitutional government when it was still politically opposed the continued existence of the Confederation, and the Confederationists supported his Confederationist-sympathies and anti-Federalist history and positions. When Dearborn won the presidency, he tackled of a new political coalition in America, in his own words: “A Great Coalition where those who support limited government and those who support expanded federal powers work to find a middle ground of compromise instead of setting up opposing governments.”

Dearborn was officially a member of the Federalist Party for political reasons, but his choice for Vice President was James Monroe and his entire Cabinet was full of Federalists and Confederationists. His Great Coalition was destined to last, for a time, and lead the United States for the next twelve years, only coming to an end with the rise of the Republicans. That is not to say that his presidency was uneventful or without its challenges. A great many stood before President Henry Dearborn, and the first of which would come when the United States would approach their French ally about potentially buying the City of New Orleans.

As much as I understand the love and desire for maps, I am very poor at making them and would rather only embarrass myself on rare occasions. I will have a map of the entire North Atlantic (Europe and North America) out within the next couple of parts, seeing as how a lot is going to change over that time.

Part XI: The Reluctant Federalists and the Decade of Reform

In early 1802, George Clinton, President of the Confederation, knew that the Confederation had to adapt or die. After the series of failures that brought a resurgence in popularity to the Constitutional government, Clinton foresaw that the Confederation either needed to reform or disband entirely. He called upon the remaining Confederation states to meet in Richmond, Virginia to discuss what to change and how to go about doing it. It was decided that the Articles of Confederation would be replaced with the Second Articles of Confederation. Many notable figures attended this not-exactly convention, including notable Confederationists like Thomas Jefferson, James Monroe, and Samuel Adams, along with the Irish Revolutionary War Heroes William Henry Harrison and Peyton Randolph. Peyton Randolph attended due to him and his father both being Virginia natives, but his father not being able to show up at the convention of a government he considered illegal for obvious reasons. Despite their inexperience in government, Harrison and Randolph had quite a lot of prestige among those who attended the Confederation Convention. With their experiences in Europe with revolutionary ideals in Ireland and France, they had a very different outlook than the Confederationists and the end result really shows.

Over the following years, many ideas emerged from the convention on how to change the articles to better fit what was being demanded of government. An equivalent to the Bill of Rights, called the Declaration of Rights, was one of the first documents to emerge. The Declaration of Rights went further than the Bill of Rights in some ways, including an explicitly stated right to vote for all free men and explicitly prohibiting the revocation of the right to vote for any American citizen who qualifies. There were also limits on government officials, with declarations regarding pay and term limits. Regarding pay, the representatives could raise the pay of the members of the Confederation Congress, but it could not come into effect until the beginning of the term after the next. Regarding term limits, there was a proclamation that each representative was to be limited to four three year terms, with a single three year long break before they can serve four more terms.

These changes were incredibly popular and made the general population question why the Constitution lacked them. Every states of the United States had different rules regarding who qualified to vote and the vast majority of them limited people to only landowners.

The next document that was released by the Confederation Convention came a year and a half later, in November of 1803. It was called the Declaration of the Legislative Branch and formally recognized the authority of the Executive and Judicial Branches of the Constitutional government as fulfilling the same role for the Confederation government. While it acknowledged the existence of the Constitutional Congress, it proclaimed that the Confederation Congress would continue on as its own separate and distinguished legislature. Some hardline Confederationists saw this as an act of surrender but nearly everybody else agreed that it was for the best. Now the Confederation states would be counted as part of the Electoral College and the President of the United States would be the president for the entire United States. This declaration also changed the title of the head of the Confederation Congress from president to consul, in reference to the new co-consuls out in France. This titling was considered incredibly controversial, as most Americans saw this move as an unjustified coup, but it passed nonetheless. The position of consul could only be held for one entire term, three years. Somebody could become consul twice, but not in a row and not any number above that. Another provision stated this document stated that any state could leave the Confederation Congress any time they wished, but only by ratifying the Constitution and joining the Constitutional Congress, like what Vermont had done. The Confederation Convention also resolved the matter of the placement of each institution. Believing that too much of a bias would form if they were in the same place, the Confederation only agreed to recognize the authority of the President and the Supreme Court if the President relocated to the City of Philadelphia and the Supreme Court relocated to the City of Richmond. The Constitutional Congress remained in the Federal District, which would soon be renamed the District of Washington in honor of the deceased first president and commander-in-chief.

The last provision is what kept this document from being released at the same time as the Declaration of Rights. Many at the Convention argued against it but in the end Peyton Randolph and William Henry Harrison managed to get it through and had to wait for the Constitutional Congress to do the same. Each state of the Constitutional Congress would have a single representative in the Confederation Congress and each Confederation state would have a single representative and a single senator in the Constitutional Congress. This was to make the two separate legislatures become more integrated while remaining as entirely separate institutions. Although this last bit was not a formal provision, it became the de facto law of the land that Amendments to the Constitution and Declarations of the Articles were on equal terms of political power and that neither applied as overarching laws of the land. The only things that could were Supreme Court rulings where both the Constitution and the Articles were being questioned, which would rarely ever happen.

This was all set in stone by the Presidential Election of 1804. The election would become a landslide victory for Henry Dearborn. Dearborn was the perfect choice by the now formal Federalist Party, headed by Alexander Hamilton who otherwise lived in total obscurity. Going into the election, Dearborn was universally loved as a war hero and liberator. The Federalists supported his service under the Constitutional government when it was still politically opposed the continued existence of the Confederation, and the Confederationists supported his Confederationist-sympathies and anti-Federalist history and positions. When Dearborn won the presidency, he tackled of a new political coalition in America, in his own words: “A Great Coalition where those who support limited government and those who support expanded federal powers work to find a middle ground of compromise instead of setting up opposing governments.”

Dearborn was officially a member of the Federalist Party for political reasons, but his choice for Vice President was James Monroe and his entire Cabinet was full of Federalists and Confederationists. His Great Coalition was destined to last, for a time, and lead the United States for the next twelve years, only coming to an end with the rise of the Republicans. That is not to say that his presidency was uneventful or without its challenges. A great many stood before President Henry Dearborn, and the first of which would come when the United States would approach their French ally about potentially buying the City of New Orleans.

Last edited:

Part XII: The Haitian Revolt