But this was made up for by the tropical disease. The ships would spend around 60 days buying slaves, anchored in river delta, A.K.A malarial swamps. There would be a large spike of deaths here.

In the 19th century, British troops stationed in Africa had a

48%-67% annual mortality rate! African troops had a 3% annual mortality rate.

During the same period the British reported that white troops in the Caribbean had about a 300% chance of dying in a given year compared to black troops. Not every island was highly malarial during this period, however, so mortality may have been much higher in localized areas.

It's also true that all parts of Latin America, tropical and non-tropical, experienced constant and masssive Iberian immigration in all its colonial history. Spanish and Portuguese people makes up a large number of the total population of some tropical areas on which there was virtually no immigration in 19th Century and in the early 1900s: they are 30% of Northeast Brazil, 30% of the Dominican Republic, 20% of Colombia and Venezuela, etc. All these regions have much worse climates than the South.

I'm sorry, I think you're wrong.

Wiki has some figures for Brazil. From founding through the 17th century, around 100,000 Portuguese settled. In the 18th century, another 400,000 did, due to the gold rush. Most of this was concentrated in the uplands of Minas Gerais, which is not an unhealthy area for Europeans, along with points further south (which were also, generally speaking, either not malarial or only barely so). In addition, since Brazil never had an issue with race mixing, most "whites" who aren't from 19th century stock are actually partially (10%-15%) black or so, thus they might have the Duffy antigen to protect against malaria).

As to Latin America, it's harder to say, because either the Spanish didn't keep statistics as well as the Portuguese, or these haven't made it into common sources. I do know, however, that Cuba experienced a big racial turnover due to Spanish Immigration in the late 19th century. In 1841 Cuba was only around 41% white and 59% non-white, but by 1877 it had become 67% white and 32% non-white. Columbia received very little immigration in the late 19th century, but Venezuela did to some degree. And virtually everyone in the Dominican Republic is mixed race (most would pass as black in the U.S. sense, even if they are predominantly white by genetics).

American South climate is somehow more related to Southern Brazil and Argentina, regions settled mostly by European small landholders and artisans. In absolute numbers, however, most of the Brazilian immigration went to the State of São Paulo not to only populate the place, but to replace African labor at the subtropical coffee plantations.

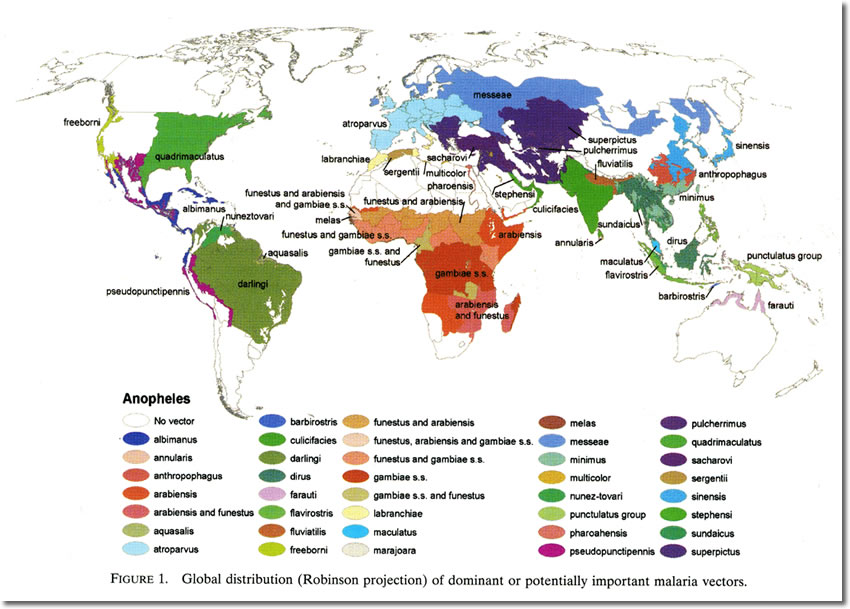

While this might be true in terms of overall climate, the genus of mosquitoes which is the vector for malaria was absent from Argentina and far southern Brazil. Malaria couldn't infect the native mosquitoes, which were not closely related.

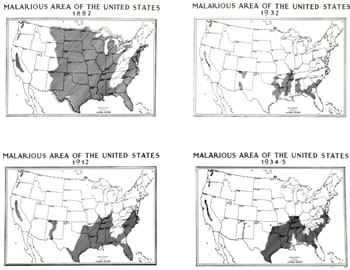

As a result, in South America, it was more the presence/absence of the mosquito vector which mattered, but in the north, it was more the average temperature, as the African form of malaria needs a few consecutive weeks of temperatures above 66 degrees Fahrenheit to propagate successfully.

As an aside, Argentina did have lots of slaves imported - somewhere between 220,000 and 330,000 between settlement and the abolition of slavery. But similar to New England, they didn't have any vital economic sector that free labor was competed out of, so slavery left no mark on the nation.

My point is that the very nature of settlement was as related to the cultural aspects of the colonizing country as to the economical and geographical features of the colonized area.

Culture matters little to none. There were many attempts for Europeans to form new cities in tropical lowlands New World, and almost all of them failed miserably. In contrast, whites settled quite well into the highlands and high latitudes. It's why most Spanish settlers in the 17th century moved to Mexico or Ecuador.

It's true that the slave price will goes down if we think about a short term crisis of profitability, but if we assume a long term unviability of these crops, slavers would just turn to the Caribbean and to Latin America. In addition, besides the rice production, I don't actually see any other use of slave labor in the American South without cash crops. Lumbering and cattle hearding never were compatible with Slavery.

The Dominican Republic managed to get slavery to work with cattle ranching. Nonetheless, you have a point.

Still, my main point is not that slavery was inevitable in these areas, it's only that without African labor, large portions of the coastal lowlands and Missisippi bottom-lands will be viewed as marginal if not useless lands. I see it developing without slavery sort of similar to the Amazon (albeit to a lesser degree), which has always had many valuable resources, but was such an unhealthy climate for whites up until the 20th century it was left to Indians and the decedents of runaway slaves.