The Lion in Winter

Part 11

1502-1516

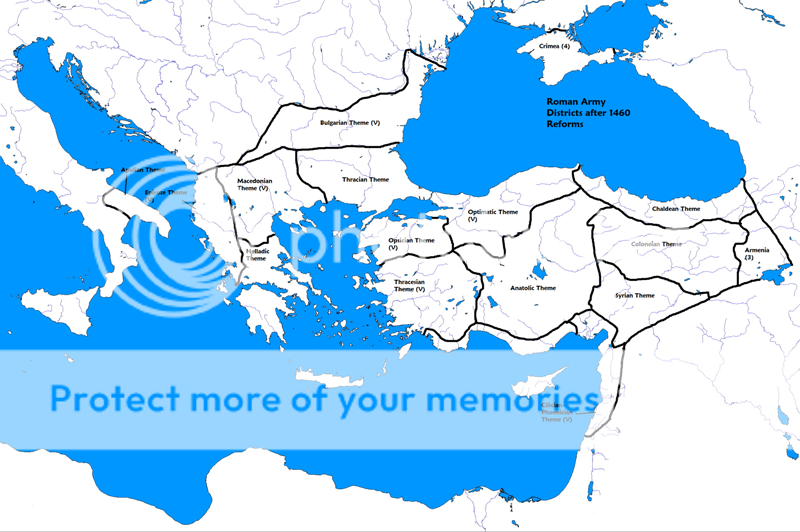

"Andreas I Komnenos had 8 sons, and 150,000."-A History of the Rhomanian Army (note that Roman historians do not consider Andrew of Hungary a son of Andreas Komnenos)

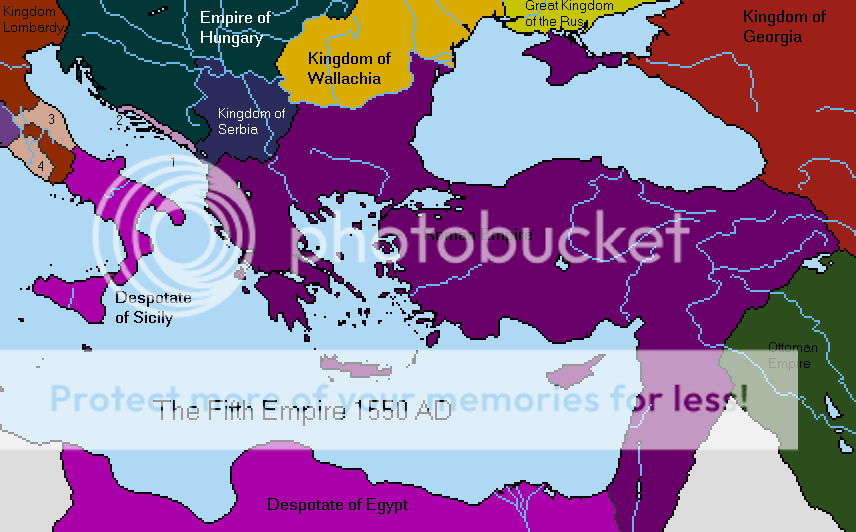

Brown- 80+% Orthodox

Green- 80+% Muslim

Tan- 80+% Noble Heresy

Yellow- 50 to 75% Orthodox

Orange- 33 to 49% Orthodox

Red- 21 to 32% Orthodox

Note that the dominant religion in Cilicia is the Armenian Church, and in the Nile Delta is the Coptic faith. In Italy, the two major centers of Roman culture are Bari, Venetia, and Syracuse. Venetia is too small to appear on the map, but would be brown. The red in the Crimea is the former Genoese colony of Vospoda, and Tana (off map) would be red as well. The Serbian vassals are overwhelmingly Orthodox, Al-Andalus is overwhelmingly Muslim, and the Italian vassals are overwhelmingly Catholic. But the Italian ducal families are all Orthodox, and the creed is starting to trickle down amongst the major landowners and merchants, but the farmers and artisans remain completely untouched.

1502: The sack of Cairo sends ripples throughout the Muslim world. Everywhere there are at least some rumblings, but the main explosions come from opposite ends of the House of Islam. In India, it helps trigger a mass Muslim revolt against the Vijayanagar Empire in the coastal cities of Gujarat and Maharashtra. There has already been much dissent against the oppressive and discriminatory Hindu rule (for starters, Muslims are not allowed to own horses or buildings with more than one story, and are taxed three times more heavily than Hindus). Vijayanagar’s collaboration with Ethiopia in the Meccan campaign is also remembered, and not forgiven.

The Sultanate of Delhi invades to support its co-religionists, making as far as Pune before it is met by the assembled might of the Vijayanagar Empire, forty thousand infantry, sixteen thousand cavalry, and two hundred and ninety armored war elephants. The trumpeting behemoths are decisive in the smashing victory, coupled with the mercenary Timurid gunners in their howdahs.

But four days later the Muslim fleet annihilates the Vijayanagara navy off Kozhikode with the first known use of bomb ships outside of the Mediterranean. Without naval support, the Vijayanagara army is unable to reduce the coastal cities as Ottoman and Omani vessels make huge profits ferrying in food and armaments.

In North Africa, something too is stirring. Ali al-Mandari, one of the leading men of Tetouan, who had been ruined by Roman merchants in Al-Andalus and moved to Africa to rebuild, takes five galleys out into the Mediterranean to wage the jihad fil-bahr, the Holy War at Sea. In six weeks, he takes one Roman transport, laden with silk and sugar, and two Aragonese galleys. His example is immediately followed by sailors and tribesmen from Safi to Bizerte.

The overlord of all these jihadists, the Marinid Sultan in Marrakesh, does nothing to curb these raids, but instead encourages and shelters the raiders in exchange for a cut of the profits. With peace in Egypt, Carthage’s brief ascendancy as the premier supplier of plantation slaves for Rhomania is over, so he has little incentive to not harass Roman traders. These raids also serve to bolster his prestige as well as his coffers. The effective loss of al-Andalus without a fight is extremely embarrassing, and enforcing payments from the corsairs is a good way of reasserting his authority.

The rhetoric is couched in that of holy war, and for most of the participants, it is a holy war. But the jihadists soon begin attacking Andalusi vessels as well, viewing them as traitors to Islam. For they willfully exchanged a Muslim for a Christian ruler, and not only that, they chose the one responsible for the conquest of Jerusalem and the destruction of Cairo (in the Maghreb Andreas is viewed as the destroyer of Cairo due to ignorance about the Ethiopians). As such, they are treated as Christians; captives are impressed as galley slaves.

The Andalusi do not take kindly to being on the receiving end of a jihad. When two corsair ships are captured off Almeria in September, the crews are slapped into chains and then thrown into the sea.

In Constantinople, on April 19, Herakleios is crowned as junior Co-Emperor of the Romans, with the imperial mint issuing new coins showing both Andreas and Herakleios. Present are his two older sisters, Helena and Basileia, Crown Princesses of Russia and Georgia respectively. Almost immediately Andreas turns over much of the Imperial administration into his son’s hands.

There is relatively little dissent. Few of Vlad’s appointees remain after all this time, and the few that do are part of the army and have long since come over to Andreas’ side. The clergy mutter, but for the most part are appeased by the Cairo Proclamation’s restriction on Catholics or Muslims in the tagmata. Also smoothing their feathers are several grants of land in the Holy Land to the church, including the Biblical towns of Hebron, Jericho, and Nazareth. All of them are placed under the authority of the church, providing taxes after a four-year remittance period are paid.

There is also the fact that there is no clear better choice. Some prominent priests, including the bishops of Adrianople, Dyrrachium, and Larissa, believe Demetrios to be a closet Copt. Others suggest Theodoros, and while Andreas has done much to support his son’s menagerie, he states that anyone placing Theodoros on the throne of Rhomania will do so over his dead body. A rumor spreads that the bishop of Adramyttion remarked that the suggestion wasn’t so bad. The next day a mob wrecks his house in Constantinople.

Andreas is not in the Queen of Cities when that happens. He spends most of the year back in Syria, overseeing the first major training exercises of the south Syrian tagma. His primary mission now is to get them and both Egyptian tagmata into fighting shape as soon as possible, as he is alarmed by the rapid increase in Ottoman domains. He also finds the warmer climate of Syria and Egypt to be much pleasant than Constantinople.

In Persia the formal investment of Fars begins in May, Konstantinos Komnenos again commanding, as Andrew of Hungary drives the last of the demoralized German forces out of his domains. The new twenty-two year old Holy Roman Emperor Manfred I Wittelsbach has managed to rally his Bavarian troops, but is having more difficulties in keeping the other German princes in line, particularly after his loyal ally and vassal Archduke Antoine, Lord of the Westmarch, is resoundingly defeated by a relief Dutch army at the siege of Rotterdam.

But it is in southern France that sees the most action of the year. The armies of France-England move rapidly, even as Louis I moves equally as fast to marshal the Arletian lances. The French-English offensive is focused on the west, both to avoid the war in Lotharingia and to forestall a rumored Arletian plot to seize the main convoy bearing Bordeaux wine to England with the help of the Castilian navy. Their primary target is Toulouse.

Louis’ son and heir, Prince Charles, commands the main Arletian army, seventeen thousand strong accompanied by thirty Bernese battle cohorts, three thousand men. Leo Komnenos, commanding another three thousand men, has orders first to spoil a large raiding party rampaging along the Rhone before meeting with the main body. This he does quickly, smashing the two thousand French-English at Valence and inflicting quintuple the number of casualties he receives. Marching hard, he has almost joined Charles at the town of Merles when thirty thousand French-English assault Charles.

The heavily outnumbered Arletians and Bernese are quickly thrown on the defensive, even though three sharp ripostes from the cohorts stagger the Plantaganet right. The roar of the battle comes as a surprise to several of Leo’s officers, as it is coming east of the expected rendezvous point. When they ask Leo what to do, he replies in words forever remembered by the Arletian people. “We march to the sound of the guns.”

Ninety minutes into the fray, Prince Charles has been outflanked and the Bernese are on the verge of being surrounded, though they bitterly contest every inch of ground. The French-English commander, the Duke of Berry, has every expectation of victory when the west explodes with a mass crescendo of hellfire. Three arquebus volleys blast the Plantaganet right flank at point-blank range, trumpets screaming as Leo charges at the head of twelve hundred heavy Arletian lancers.

A modern rendition of

Leo Komnenos at the Battle of Merles, for the game

Century of Blood

The French-English line does not waver, bend, crack, break, crumple, or shatter. Instead it ceases to exist. As Leo rolls up the Plantaganets, Charles and the Bernese immediately counterattack, the onslaught of the Habsburg knights killing the Duke of Berry as he desperately tries to restore order. When he dies, all hope of saving the army dies with him. Between the battle and the five-hour pursuit until sunset that follows, the French-English host is effectively destroyed as a fighting force.

Still the Arletians and Bernese suffered heavily, over twenty five hundred casualties. One of those is a man whose arm was broken by Leo for looting. His crime was not the looting itself, but that he had dismounted whilst the enemy was still on the field to do so. Once they have been cleared though, Leo has no problems with his men pillaging the enemy camp and raping the camp followers.

Though somewhat disgusted by Leo’s post-battle activities, Charles does concede that the Roman prince turned certain defeat into a smashing victory. And the Bernese League also remembers its sons who were saved, including no less than nineteen scions of the Habsburg family. So two months after the battle, Maximilian von Habsburg, Count of Breisgau, Zurichgau, Thurgau, and Aargau, formally legitimizes Leo’s wife Klara.

Basileios von Habsburg-Komnenos, son of Leo Komnenos and Klara.

1503: The defeat at Merles is a harsh blow to Plantagenet hopes of an early victory, but it is by no means a fatal blow to the war effort. As spring dawns, levies are gathered across southern England and northern France. The quick start to last year’s campaign comes as a hidden blessing, as the majority of the formidable artillery train and the bulk of the French aristocracy had not been assembled and committed.

As Arletian forces move up the Garonne, the Plantagenet counterstrike gathers in Normandy when two balingers put into Calais with news from the north. Northumberland is burning.

A Scottish army has crossed the frontier burning and pillaging, the shires mustering in response, only to be caught completely flatfooted when a Norwegian fleet of nine thousand men and a hundred and twenty ships falls upon the coast. Caught between two fires, the men of Northumberland are engaged at Flodden Field and utterly annihilated. The combined Norwegian-Scottish army flies south, the Norwegian navy joined by fifteen Scottish vessels including two small purxiphoi, harrying the coast as far as Kent.

Scots warship in action off East Anglia

Newcastle-upon-Tyne defies the invaders, hurling back one attempted assault with hastily fabricated catapults made from the timber of torn-down houses. But everything else north of the River Tees is at the mercy of the Norwegian-Scottish army. Haakon VIII, King of Norway and Scotland, had skillfully exploited the marriage ties forged by his father Haakon VII with his twelve daughters to gather artisans and soldiers from across all of Europe. The result is that the Norwegian artillery train, though comparatively small, is one of the finest in all of Europe.

As Scots and Norwegian warships prowl the North Sea and even raid into the Channel, mopping up every English or French vessel they can find, Alexander MacDonald, Lord of the Isles, chief vassal of the King of Scotland, puts out to sea with his own armada. Almost immediately he turns the Irish Sea into his private lake, his galleys raiding the coasts of Ireland, Wales, and Cornwall.

King Edward VII, faced with the alarming possibility of losing control of the sea, authorizes the sailors of England and France to wage war by privateer (some had already started). The men of the West Country, the Cinque Ports, and London respond vigorously. The ships from London, large and well-armed (many with royal armaments illegally purchased from corrupt Tower officials), prove particularly dangerous. However the privateers have a tendency to turn pirate, and Danish and Hansa merchant ships soon become a preferred target. More alarming though is three attacks by men from Portsmouth and Plymouth on Castilian carracks bearing cargoes of wool for Antwerp.

The inhabitants of the Low Countries are also annoyed by the transformation of the Channel and surrounding seas into a war zone. In the first six months after Edward authorizes privateering, thirteen Dutch vessels are taken. This is somewhat compensated by the fact that Scots and Norwegian vessels typically sell their prizes and cargo in Dutch ports rather than take them all the way home.

Almost all of the French-English naval effort is waged by private citizens. The embarrassing fact is that the royal navy is extremely under-strength. Most of the funds have gone into the army, in particular to restoring the artillery lost at Cannae. Half of the king’s ships are leaky, and all are undermanned. On paper they are at full-strength, but the ships’ masters have been skimping on their crews and pocketing the extra wages.

There is similar corruption amongst the quartermasters. Provisions are universally late, often too small, and frequently corrupt. Provided with rotten meat, moldy bread, their pay at least six months in arrears, and forced to run a ship that needs a hundred men with seventy, it is little surprise when most of the crews mutiny. Five ships do sail, but turn pirate when they spot a small convoy carrying pay for the army in France. The chests of gold and silver, containing 60,000 pounds sterling, over an annual year’s revenue for the Kingdom of England, is stolen.

France-England is not the only one suffering, as Andrew of Hungary launches his invasion of the Holy Roman Empire. Sharply defeated at Linz and Passau, Emperor Manfred is swiftly losing control over his realm. An epidemic of dysentery that cripples his army forces him to abandon Munich without a fight. Andrew seizes the city, but then drives west instead of north after the fugitive Kaiser. His rationale soon becomes clear. On September 12, Mainz surrenders to the Hungarian armies, Pope Martin V of Mainz fleeing north to join Manfred in Schleswig.

Two days later, a papal legate from Avignon formally crowns Andrew in the cathedral of Saint Martin. He is now, by the Grace of God, Imperator Romanus Sacer, Apostolic (added at this time) Emperor of Hungary, King of Italy, Croatia, Dalmatia, Austria, and Bosnia, Grand Prince of Transylvania. The fact that none of the electors support this coronation is ignored.

It is the fulfillment of a century-old dream of the Arpad kings, who have been fighting for the Imperial Eagle since the War of the Five Emperors. But Andrew, his appetite whetted, is looking for more. In Mainz, he tells his heir Stephen the truth of his parentage, telling him “I have won the Roman Empire in the west. It will fall to you, as firstborn son of the firstborn son of Andreas Komnenos, to win it in the east, to restore the one, indivisible Empire of the Romans.”

1504: The Holy War at Sea continues in the waters of the western Mediterranean, the African corsairs striking at any ships that come within reach. In July the first purxiphos constructed in North Africa joins the fray, participating in a combined operation with twenty other ships. The expedition captures a Genoese convoy loaded with naval stores (for the Castilians), seizes three textile-laden barques out of Antwerp and eight other vessels, including an armed (five guns) Roman carrack, and raids the coast of Menorca, carrying over fifteen hundred inhabitants into slavery.

The only significant success against the jihadists scored that year is by the smallest of their victims, Carthage. The city-state maintains a total of fourteen galleys, although only seven are ever mobilized at once for financial reasons. On September 3, five of those galleys meet seven corsair ships off Cape Bon who immediately attack.

The Carthaginians accept the challenge, charging into battle. Just before both sides smash together to board, they fire…with Roman-army-grade Vlach shot. The charges, packed with hundreds of arquebus balls, scythe down the Muslim boarders in bloody swathes. The complements of two of the corsair ships are virtually annihilated. In the end three corsairs escape, another sinks, and the other three are towed back in triumph, to the cheers of Carthage’s people. Outsiders though have some difficulty in understanding the chorus, as the Italian of the Genoese is being steadily Berberized, along with some Greek influence.

In Persia, Fars at last falls to Konstantinos Komnenos. Although the Shah escaped before the end, and is organizing resistance in a new capital at Damghan, it is a tremendous victory. Not even Osman II made it this far. But it is soon marred. An Ottoman army marching on Damghan is ambushed and destroyed, not by a Persian force, but by a Timurid column that had swooped down from the north. The captured cannons and crews are carried back to Samarkand, where the Khan Ulugh Beg puts them to work creating his own gun foundries.

Although the nomadic tribes of Central Asia make up an important part of his powerbase, Ulugh Beg is no warlord in the vein of Genghis Khan or Timur. His capital of Samarkand is a thriving, bustling city of 120,000, with famous madrasas and one of the finest observatories in the world. There subsidized scholars write treatises on both trigonometry and spherical geometry. In 1495, Ulugh Beg had suggested an exchange of astronomers with the Roman Empire (specifically the University of Smyrna) to foster study, but the envoy had arrived during the confusion after Empress Kristina’s death and eventually returned to Samarkand empty-handed.

Construction on the first foundry has just begun when two children are born. The first is far to the northwest, and unknown to the Timurids. And even if they did, they would not care. For what does it matter that King Charles Bonde of Sweden has a daughter named Catherine? She will never amount to anything. Their new prince, on the other hand, is a different story. For he has been given the name, the name that has been silent for a hundred years, a name to make all the nations tremble. Once again, there is a Timur in Samarkand.

1505: In April, four ships offload their cargo into warehouses along the Golden Horn. It is three hundred tons of kaffos, by itself the equal of all the kaffos shipped into the Empire in the sixty years before the fall of Egypt. It is expected that a similar amount will be offloaded in other Imperial ports throughout the year. Ethiopia also provides ivory and slaves (taken from raids against pagans in the interior), but kaffos makes up four-fifths of the value of all Ethiopian exports to Rhomania.

The importance of this trade to both empires cannot be understated. Although still unknown in the rest of Christendom, Rhomania has known about kaffos for sixty years and it already has gained a market, limited only by the exceedingly high costs of the drink. In the four years since the fall of Egypt, the price of kaffos has dropped to a tenth of its former amount, placing it at a level that even carpenters or blacksmiths can afford the occasional drink. In that time the number of kaffos oikoi (coffee houses) in Constantinople has jumped from three to forty eight, serving the hot beverage in winter and iced kaffos in summer.

Besides providing Herakleios with a host of new establishments and imports that can be taxed, the kaffos oikoi will play an important role in Roman culture. Heavily frequented by students and scholars, the oikoi are important in fostering new developments in science and philosophy by providing a common and popular place for people to meet. They also prove to be a veritable fount of information, one that the Spider Prince quickly and effectively taps, although it is by no means his only or primary source.

The university kaffos oikoi (by this point all of them have at least one) are the first to introduce the newsletter. A sheet of paper, or on prominent occasions a pamphlet, the newsletters contain information about important university events and also news from throughout the Empire.

For all the future significance of the trade, which will eventually lead to the modern stereotype of the kaffos-chugging Roman, the greatest impact is on Ethiopia. It has been argued by some scholars that it made the modern Ethiopian Empire possible. Seeing how much kaffos is being exported, Kwestantinos slaps a huge export duty on it, but even that does little to stop the flow. He also legalizes its secular consumption in Ethiopia proper; previously the Ethiopian church had frowned on it due to its role in pre-Christian religious ceremonies.

Meanwhile money flows into Gonder’s coffers. The negusa nagast puts the money to good work, financing the construction of roads, bridges, towers, and ports designed to speed communications and transportation throughout his vast realm. After negotiations are completed with Katepano Demetrios, construction begins on a grand Roman highway from Alexandria to Gonder.

The owners of kaffos plantations find themselves making tremendous amounts of money, and immediately begin looking for how to make more. They quickly discover that it is faster and more cost-effective to transport the kaffos to the coast and then by ship to Suez. To that end, they foster the construction of ports, warehouses, and ships, creating the Ethiopian merchant marine virtually singlehandedly. For crews they turn to the numerous decommissioned sailors from the downsizing of the Ethiopian fleet.

With newfound wealth comes newfound taste. Having numerous contacts with Rhomania gives them an appetite for Roman goods, in particularly silk textiles, jewelry, and sugar. In particular, low-quality Roman silks are extremely popular, despite their comparative expense (on average, a Roman textile costs three to five times more than it would in Constantinople) beyond the class of kaffos merchants. The combined result is that already Ethiopia is Rhomania’s third most important trading partner, after Arles (number 2) and Russia (number 1, whose trade is worth is more than Arles’ and Ethiopia’s combined).

1506: The North African corsairs expand their range of operations, raiding the island of Elba, although an attempt to harry the coast of Provence is literally blown out of the water by the Arletian fleet. The Aragonese fleet, which is the premier power in the western Mediterranean, has like the French-English been suffering from a wave of graft and corruption, as King Jaime VII’s failing health makes it difficult at best for him to keep an eye on his officials.

Yet there is little response to the pirates from the east. In March, Herakleios issues orders for ten monores to reinforce the naval squadrons at Palermo and Malta, while four more plus a dromon are assigned to Valencia. Andreas does not intervene in the arrangements; he is in Jaffa with Empress Veronica and Prince David, commanding joint exercises of the south Syrian, Egyptian (more properly West Egypt), and Augoustamnikai (East Egypt) tagmata.

The reason is that the vast majority of the funds for the navy are being poured into a new project. A primary fleet base has been established at Suez, along with a support base at Aqaba, as well as a forward anchorage for lighter warships at Marsa Alam. The importance of these bases to Herakleios is clearly shown by the fact that the second full-fledged naval dry dock to be built is at Suez (the first is of course at Constantinople, receiving its first ship in 1501).

Besides building and paying for the necessary docks, warehouses, workshops, and barracks for the new bases, it is also quite expensive getting ships from the Mediterranean to the Red Sea. The rehabilitation of the Pharaoh’s Canal begins as well, an expensive, labor-intensive operation. Although it will take many years before it is ready, and be far too small to accommodate even the smaller warships, it can be used by flat-bottom cargo barges. To supplement it, the canal is flanked by a series of roads.

An unwelcome side effect is the boon the whole project is to Cairo’s revival, since the crippling of a Muslim metropolis that could rival the Queen of Cities was a welcome side effect of the Sack of Cairo. The importance of cities in Hellenizing the countryside, by drawing in young men and women searching for work and study, is evidenced by the fact that the region of Orthodox Antioch is also majority Orthodox, while the area surrounding Muslim majority Aleppo is also mostly Muslim.

A few light vessels are constructed at Suez, but all the heavier warships are made at the Arsenals. The galleys, with their prefabricated components, are relatively easy to dismantle, portage, and reassemble at Suez. To support this operation, a road network springs up linking the two Red Sea ports and the Mediterranean coast. The much larger purxiphoi, some of which like the Justinian weigh 1200 tons, are significantly more difficult.

To help solve the issue, Herakleios turns to a promising young shipwright and sailor named Kastor Diogenes, who had sailed on Genoese carracks on three Antwerp runs, Portuguese caravels on two visits to Madeira, and on a Norwegian barque that was part of the annual Greenland convoy. Admittedly that is not what caught the Emperor’s eye; it was his jibes that the only god he worshipped was Poseidon, which had earned the ire of the Arsenal priests.

Despite his unorthodox religious beliefs, when it comes to building ships those priests cannot deny that Kastor knows what he is doing. In 1500, his rebuilding of the old purxiphos Autokrator took only forty five instead of the projected fifty five days, with a corresponding decrease in cost. When Herakleios gives him this new assignment in 1504, it is a chance for him to put the lessons he learned in the Atlantic to practice.

The result, which first slides into the Golden Horn in August 1505, is confusingly for naval historians called a dromon (a shortened form of Kastor’s original term ‘great dromon’), the same as the oared battleships that make up the bulk of the Roman fleet. They are skinnier and longer than purxiphoi, which makes them better sea handlers but also enables them to sail further up the Nile than purxiphoi, reducing portage costs.

To decrease weight, the aft castle is shortened, while the forecastle almost completely disappears. Portuguese vessels have been moving steadily in that direction for forty years, finding the less top-heavy vessels more seaworthy. The reason that the forecastle shrinks much more than the aft castle is that it is common practice in all European navies to place some of the heaviest guns as bow chasers.

Before that was done, it was found that galleys, which mounted their biggest cannons in the prow because of the oars, had the advantage in the initial approach to battle, which could be decisive. With the emphasis on reducing top-heaviness, it is natural that the forecastle with its heavy weapons shrinks more than the stern castle laden with smaller guns. This also gives the bow a more galley-like look, which is why the new design is called a great dromon.

The Fleet at Suez by Andronikos of Kotyaion, 1511

1507: The reason for all the naval buildup and innovations is not a pressing need for Roman sea power in the Red Sea. With the Ethiopian fleet very friendly and the Omani one moderately so (both because of Ethiopian intermediation and Omani desire for Rhomania to act as a counterweight to the Ottomans), the ships of the Hedjazi and Yemeni are no threat. It is not the Red Sea or Arabia that draws Herakleios’ interest, but India itself.

The wealth pouring in from the kaffos trade has opened Herakleios’ eyes to the possibility of a similar onrush of even more valuable and exotic goods, spices and pepper. These commodities have been a significant part of Roman trade for centuries, and the prospect of controlling the source, or at least cutting out some of the middlemen, is extremely tempting. Using Indian and Arab merchantmen as sources of information, it becomes plain that the time to strike is now.

India has never been united, ever. A vast, diverse region, even its great empires have been decentralized states, prone to fracture into smaller, more cohesive components. Though just a few years earlier, India only mustered three states, they seem to be in the process of fracturing. The Muslim ports of Gujarat and Maharashtra are all independent city-states, squabbling with each other as long as Vijayanagar is not immediately breathing down their neck. Bihar is troubled with revolts in Bengal and Assam.

Meanwhile long-suffering Delhi has not had its fortunes improved by its Timurid Sultans. Facing powerful, hostile neighbors and entrenched corruption and nepotism in the administration, plus a falling-out with their Timurid cousins in Khorasan over Vijayanagara hires of Khorasani mercenaries, the Sultans have been hard pressed at best.

Currently the Sultanate is in an unwanted, unplanned border war. With the news of the Sack of Cairo, several bands of ghazis had decided to strike back for the House of Islam, and picked the nearest target, Swati Kashmir. The Kashmiri were not amused. The retaliation spurred more raids, which spurred more retaliatory strikes, and now not a month goes by without some skirmish in the Punjab.

To help finance the operation, Herakleios arranges for other financial backers to contribute, in exchange for a prearranged percentage of the profits. The Argyropouloi and Eparchoi families, some of the wealthiest jewelry and silk merchants respectively in the Empire provide some of their wares as trading goods. The Rhosoi of Trebizond, major shipwrights, equip two ships in the Red Sea at their own expense.

There are some issues on the part of the private backers in transferring money for their workers in the Sinai. To alleviate the risk and difficulty involved in shipping large amounts of bullion, Herakleios allows them to deposit their coinage at the Imperial Mint in Constantinople. The clientele are then given a certificate, which can be used to redeem the same amount of currency at the Alexandrian mint. This service comes at the cost of a holding fee, but soon takes off in popularity with numerous merchants using the mints and certificates to transfer capital throughout the Empire.

The result of all this nautical and financial engineering comes to fruition at the end of the year, and is known to all Roman schoolchildren as the Pepper Fleet.

Sebastokrator: A purxiphos of eight hundred tons, forty guns.

Aghios Nikolaios: A great dromon of four hundred tons, twenty five guns.

Aghios Giorgios: A great dromon of four hundred tons, twenty five guns.

Aghios Loukas: A great dromon of three hundred sixty tons, twenty two guns.

Nike: A great dromon of three hundred sixty tons, twenty two guns.

Anna: A carrack (similar to a purxiphos but intended as a cargo, not combat vessel, although capable of being armed) of two hundred forty tons, ten guns.

Petros: A carrack of three hundred thirty tons, fifteen guns.

Helena: A carrack of six hundred tons, eighteen guns.

1508: The Pepper Fleet, riding the monsoon winds, departs in the spring, joined by the Ethiopian purxiphos Solomon off Zeila. Their port of landfall in India is Surat, one of the largest and most powerful Gujarati city-states. Despite the heavy armament of the fleet, the focus is on trade, not conquest. Using the Plethon-Medici agent (the ludicrously rich family has agents as far away as Antwerp and Malacca as part of their mercantile network) already in port as an intermediary, the traders set up shop to sell their wares and purchase local goods, primarily pepper.

But things very quickly get out of hand. The Muslim merchants are not enamored of this new, strange competition. One or two Roman agents was acceptable and unthreatening, but this heavily-armed squadron is another matter. When a few Ottoman merchants spread a few words about exactly whose these newcomers are and what their countrymen were doing in Egypt a few years earlier, the tense situation immediately explodes.

A riot overruns some of the Roman stalls but is quickly dispersed by a few volleys of gunfire into the crowd. The westerners retreat to their ships, but negotiations with the Emir of Surat go nowhere. On May 1, a few dozen bravos try to light the Pepper Fleet on fire during the night, a brave but futile attempt. Those who are unfortunate enough to be captured by the enraged sailors are weighed down and thrown into the harbor. That morning, the fleet sets sail but not before shelling the waterfront.

As the monsoon winds are still against them, and their cargo holds largely bereft of pepper, the Fleet sails south. Similarly hostile receptions come from the other free city-states, who dislike the combination of religious and economic competition. Off Kozhikode a small squall temporarily scatters the ships, and the Aghios Loukas is beset by a squadron from that port. Although outnumbering the Roman warship nine to one, the Kozhikodan paraus, comparable in size and capability to a cannon-less monore, have absolutely no answer to her thunderous broadsides. Two of the paraus are roughly handled, at which point the squadron withdraws.

Finally the Pepper Fleet arrives at Alappuzha. A picturesque port crisscrossed by canals, it is called by some of the Venetian sailors the ‘Venetia of the East’. More importantly, the Vijayanagara Emperor Deva Raya II is there. His agents among the free cities have given him some word of the Pepper Fleet’s action, and he is eager to see this new force for himself.

He is delighted by what he finds. The massive size of the warships, dwarfing anything seen in India, and their gleaming arrays of cannons, are very appealing. Although India is no stranger to gunpowder or cannons, the Roman and Ethiopian pieces hold sizeable advantages in range and hitting power. He immediately begins negotiating with the Roman commander, Iason Laskaris.

As the admiral and Emperor talk, the merchants get to work. Roman jewelry sells rather well, but the silk textiles face stiff competition from native manufactures and do not fetch nearly as much of a profit as expected, but the lower-quality garments which are specifically designed to be affordable for the lower classes make some headway (the high-quality items are fighting against upper-tier Indian and Chinese silk and thus seriously disadvantaged). Also Ethiopian ivory and kaffos prove to be quite successful, so steadily the holds of the Pepper Fleet are filled with cloves, nutmeg, and pepper.

As the monsoon winds begin to shift, an agreement is made. The Romans are to be granted trading quarters in Alappuzha and Pondicherry, with their own church, well, and bakery, to be administered by their own laws, weights, and measures amongst themselves, in exchange for an annual payment. But that is not the most important part of the agreement, although it is something Iason had no authority to negotiate.

In exchange for Roman military aid in conquering the free cities of the west coast, they are also to be granted quarters in Mumbai, and the cities of Surat and Kozhikode in full, with complete sovereignty to be vested in Constantinople. It is an extremely, dangerously in the eyes of some courtiers, generous offer, but it is mitigated by the proviso that the transfer will only take place when the whole coast between Surat and Alappuzha is once more in Vijayanagara hands. Deva Raya II’s generosity is due to the fact that he has no chance of regaining those lands without a powerful fleet, which he no longer has.

With the monsoon now with them, the fleet departs for home, leaving behind four merchants and fifty soldiers in Alappuzha, along with a pile of trading goods. It is the merchants’ responsibilities to sell those goods for spices, storing them until they can be picked up by ships from the west.

After being gone for eight months, the Pepper Fleet sails into Suez. The cargoes are sold on the market, and the Empire goes wild. Even with the silks’ mediocre performance, the venture has garnered a sixteen hundred percent profit. Herakleios publicly censures Iason for exceeding his authority, but then appoints him commander of the Second Pepper Fleet and doubles his salary.

Although it will take a few years before it is ready, there is no doubt in anyone’s mind that it will not be a fearsome force. The number of private backers for the Second Fleet is quadruple that of the First Fleet, the Rhosoi alone agreeing to pay for four carracks. And for every hyperpyra the merchants pledge, Herakleios matches.

1509: War continues in the west, poorly for France-England. A smallpox outbreak cripples the first Plantagenet army assembled after Merles, giving the Arletians a critical few years where they are not faced by any serious opposition in the field. The main thrust is concentrated on the Garonne, with the goal of securing all of Aquitaine. Of particular concern to Edward VII is the number of Gascon fortresses that capitulate without a fight. As fellow inhabitants of the lands of the langue d’oc, in contrast to the lands of the langue d’oeil, the Provencals and Gascons have much in common, and King Louis I has been skillfully exploiting the fact.

But in Calais, the only explanation can be treason, plus an angry God. So in April Edward VII decides to kill two birds with one stone, and orders the formal expulsion of all Jews in his domain. The Provencal coast is home to a sizeable Jewish population, and there are rumors that the French and English Jews are Arletian agents in disguise.

With Germany in chaos, most of the refugees flee to Iberia, as the way to Arles is blocked by the reforming Plantagenet armies. Neither Castile or Portugal give them a warm welcome. Al-Andalus is another matter, but when four hundred Jews are captured by African corsairs just eight miles from Cartagena, the ardor of the refugees for this new land is significantly weakened.

The blatant seizure so close to a major Andalusi naval base is a testament to the amazing growth in power of the corsairs. Their ranks swelled by renegades from Europe, the pirates have been steadily expanding their pillaging. Settlements on the Canary Islands have been sacked, and steady sweeps of the powerful Portuguese fleets have proven to be of little use.

Mighty squadrons can temporarily clear an area of pirates, but as soon as they depart the raiders return. The only way to stop them is to ruin their harbors and smoke out their bases of operation. But the African coast is dotted with small harbors and the interior filled with thousands of tribesmen just waiting to fall on any European army. The Aragonese attack on Oran, one of the most prominent corsair ports, last year was an unmitigated disaster. The fleet was smashed to pieces by an autumn storm, while the army wasted away under the triple assault of dysentery, smallpox, and Algerians. The loss of over thirty ships and twelve thousand men (at least half of which now swell the ranks of African galley slaves) make it the greatest military disaster in Aragonese history since Selinus.

So the Jews look further afield, to Rhomania. Despite the dangers, at least one hundred thousand over the next decade will emigrate to the Empire from France-England via Al-Andalus, nearly all of them settling in Calabria. Due to overzealous transfers of Orthodox Calabrians to Syria, the region is somewhat depopulated and is therefore an ideal place in Herakleios’ eyes to settle the newcomers. Thus begins the famous Calabrian Jewry, of such profound importance to the history of Italy.

At least six thousand are taken captive by the Barbary pirates en route. But although Roman naval efforts are focused on the exceedingly expensive (and equally profitable) Indian ventures, Constantinople is not completely blind to what is going on in these waters. Improvements in Roman blast furnaces have raised production of cast iron, and Herakleios has funded much research into the development of cast iron cannons.

Although heavier, and prone to much more catastrophic failure, cast iron cannons cost a mere fraction of bronze weaponry, hence Herakleios’ interest. When he begins issuing orders for the outfitting of the Second Pepper Fleet, Herakleios also arranges for greater production of cast iron cannons, with the view of having iron mikropurs and culverins, and bronze great guns.

However he also makes the iron guns available for sale, and sells the designs to several gunsmiths who begin producing for the open market. The much cheaper weapons, combined with a fifteen percent cut in the cannon tax, mean that Roman ship-owners can afford much heavier armaments for their vessels.

In Germany the situation is confused, as usual. Even though Emperor Andrew is obviously in the ascendant, his flagrant disregard of the rights of the electors has alienated most of any potential princely support he could have gained in Germany. Southern and central Germany are muttering, yet under his control, but northern Germany is effectively independent of either Emperor. The other Holy Roman Emperor, Manfred, is holed up in Schleswig, clearly the leader of a doomed cause. In March Denmark invades his domains.

By mid-May Manfred is billeting his troops in the houses of Aarhus. As soon as Danish troops had rolled across the border, he had fallen on and scattered them with an army of his own, three times larger than anyone expected he had, including twenty five hundred Russian archontes, the dowry of his Russian bride. Supplementing the finest cavalry in the world were hosts of mercenaries, paid for by Roman subsidies.

Herakleios was seriously annoyed by Andrew’s self-elevation, and the chancery of Constantinople addresses him merely as the Emperor of the Germans and Hungarians. Buda’s protests have been answered by a joint exercise of the Epirote, Macedonian, and Bulgarian tagmata in Serbia (also has the benefit of cowing the Serbian princes), and the betrothal of the Vlach Crown Prince Mircea (age five) with Princess Theodora (age two), the daughter of Emperor Andreas and Empress Veronica.

Roman marriage alliances mean little in the Baltic, but Manfred’s lightning campaign shakes Scandinavia, for one of those slain was the King of Denmark himself. His successor is King Christopher III, a boy of four. The situation for the kingdom is grave; Andrew has his hands full dealing with rebellious Bohemia and a recalcitrant Saxony, so he is no help, while the fleets of the Hansa, loyal to Manfred, are beginning to lick their lips. So the Danes turn to the mightiest Catholic power in the region, Sweden.

King Charles II (note that the OTL instance of creating fictional King Charles of Sweden has not occurred) has made great steps in centralizing his northern kingdom. His own succession was a significant victory for the hereditary monarchial principle, and he has skillfully used his estates in Finland to fund schools for scribes to administer the state. The remainder of his profits have been devoted to troops modeled after Roman akrites, quite adept at fighting in woods and crushing peasant tax revolts.

He is quite happy to intervene, but not without being paid a steep price. His initial demand is angrily rejected, but two weeks later news arrives that Russian warships are assembling at Riga. No one can forget that the Emperor in the North is the son-in-law of Megas Rigas Nikolai, who can add another fifteen thousand archontes to the twenty five hundred already in Manfred’s armies.

So Denmark accepts Charles’ demand. King Christopher is to betrothed to Princess Catherine of Sweden, to be wed when Christopher turns fifteen. At the same time, Charles is appointed head of the regency council to ‘ensure the safety of his new son’. Manfred, who has no desire for war with Sweden, withdraws from Denmark after the accord, laden with spoils and significantly more prestigious than before.

* * *

The White Palace, Constantinople, April 13, 1510:

Venera walked into the bath room, the steam immediately dampening her thin silken shift. Flicking off her sandals, she pattered across the stone floor towards the hot tub, heated by stones taken from the nearby bakery ovens. Herakleios was already in there.

She was not surprised by that. Her husband, junior Emperor of the Romans, was extremely fond of the hot tubs. When he was ill, it was almost impossible for him to stay warm, save in the tubs.

His eyes had been closed, but they flicked open as she approached. He had been doing better though these past couple of weeks, as spring blossomed. He’d eaten twice a day the past three days in a row, much improved from that worrisome spell in January where he ate a mere three times in ten days.

“Are the servants gone?” she asked innocently as Herakleios stared at her hungrily, her thin shift clinging tightly to her body. The look in his eye answered the question. “Good.” Slowly, ever so slowly, she began to strip, peeling the silk from her thighs. A giggle caught in her throat as she saw the boyish grin on her husband’s face.

This is ridiculous; we’re both adults, a part of her thought as she gently starting peeling the garment from her shoulders, going teasingly slow. That’s true, another part thought, and I don’t care. In between their responsibilities as Emperor and Empress, and the strain of Herakleios’ disease, they had to be so serious, so often. Her hand started trembling in rage as she remembered having to listen to the Bishop of Nicomedia prattle on about Herakleios’ habit of skipping services. That’s because he’s too busy bleeding out the ass! If God wanted him to go to church, maybe he should fix that first!

“Is something wrong?” Herakleios.

“No…I don’t think so,” Venera replied, revealing her naked breasts. “Do you?” she cooed. Herakleios shook his head no hurriedly. This is our time, and if we want to be silly, so be it.

“So did you hear what Andreas Angelos did?” she asked, shrugging off the shift. Again Herakleios shook his head no. His bastard half-brother was in Syria, fighting some Arab tribe that had pillaged the frontier. “He stole his commander’s underwear…” she pulled her own off… “…attached it to a kite and flew it toward the enemy’s camp.” She tossed it aside.

Sliding into the tub opposite from Herakleios, she continued. “Three days later the tribe surrendered to him, not his commander. Andreas contends the events are related.”

Herakleios nodded. “He’s probably right,” he said, his eyes following Venera’s hand as she dappled some water on her cleavage.

“He’s quite a character, don’t you think?” she asked, stretching her legs so that her toe traced his calf. “He still calls the Empress Veronica ‘that tavern wench’, except when she has that crossbow handy, of course.”

“Mm, hmm,” Herakleios grunted.

Venera smiled; she loved playing this game, seeing how long her husband could hold out with her teasing him. “Surrender already?” she asked, arching her eyebrows.

For a second, Herakleios was silent, but then his will to resist crumbled. “Oh, yes.”

Venera grinned, sliding over towards him. “That was easy,” she said, settling onto his lap. “I don’t think you’re putting up much of a fight.”

“You don’t fight fair.”

“And you like it that way,” she replied, kissing him. “Now what do I want, now that I’ve won? Hmmm…” She thought, scratching her chin and sliding forward. Herakleios was relatively tall, but Venera was even taller, more than even most men, so her breasts were right up in his face. “Hmmm, I just can’t decide.”

“Women,” Herakleios muttered.

She put a hand under his chin and tilted it upward so their eyes met. “What was that, honey?” she asked, coyly.

“Oh, nothing.”

Venera nodded, kissing him on the forehead. “Now, where was I? Ah, I was deciding what I wanted. I just…” She nipped at his ear. “can’t…” Nip. “decide.” Nip. “Ah, the hell with that, I’ll just take you.”

“Finally,” Herakleios muttered, sighing in relief.

Venera burst into laughter, her body shaking. “Worried that I’d keep that up for, oh, twenty minutes?” she teased, caressing his cheek. He nodded, exasperated. “Oh, you’re too easy.” A pause. “You’re also cold.” The water was cooling, since with the servants gone there was no one to add hot stones to replace the cool ones. “But don’t worry, I’ll keep you warm.”

They kept each other very warm.

Venera of Abkhazia, Empress of the Romans, from The Komnenoi, Episode 103, "The Twins"

* * *

1510: The court at Constantinople does not pay much attention to the developments in the north. For in late April, Prince Konstantinos, son of Herakleios and Venera, catches tuberculosis. For a while, it looks like he might live, but on May 3, the end comes swiftly. At the hour of Vespers, the prince dies in his mother’s arms.

* * *

Constantinople, May 7, 1510:

Nikephoros was happy. Konstantinos was dead, killed by poison in his medicine. Without an heir, Herakleios looked less useful as an Emperor. And now it was time to celebrate.

He rounded the corner, and there it was, The Captain’s Daughter, one of Herakleios’ brothels. Nikephoros would give that to his uncle, he knew how to make money. The Emperor owned over two hundred brothels across the Empire; most were in the old Mameluke Sultanate, taking advantage of the fact that they were filled with young, bored garrison soldiers far from home. But there were some in the Imperial heartland, and no less than four in Constantinople. But this one was Nikephoros’ favorite.

He opened the door, but then his eyes darted over to a nearby dentist’s shop. He felt like he was being watched. There was no one there, but a man blandly glanced at him, then continued on his way. He looked familiar. Do I know him? The squeal of a girl inside distracted him. Nah. He entered.

Immediately Fatima, an old Arab battle-axe, a former prostitute and head of the establishment, looked at him. He held up a finger and she nodded him toward the room. She knew what he wanted. Fatima had a wide variety, which is why Nikephoros liked the place, including two girls from the Zanj and one from far Cathay, whom he’d all tried. But he had one particular woman that was his favorite.

He opened the door and sat on the bead, seeing the shape of Natasha’s voluptuous body behind a silk curtain. She came out, absolutely nothing on, but she’d carefully arranged her long raven hair so that it covered her breasts. “Milord wants me tonight?” she purred, sitting on his lap. Even though his silk pants, he could feel her body heat.

“Yes. You have done very well.” She’d successfully completed her third assignment, stealing the land deeds of the Macedonian tax prefect, proof of the official’s illegal purchases of estates outside the capital. Her next would be an assassination. If she was as skilled with the knife as she was in bed, he would have much use for it. He squeezed her breasts, the Russian moaning. “Oh, yes. Very well indeed.”

* * *

But whatever joy the Prince of Spiders feels at the death of Prince Konstantinos soon dissipated. For at the beginning of the next year, two women give birth. The first is the wife of Andreas Angelos. The jokester has a son, who is given the name Isaakios. The second woman is Empress Venera herself. On January 17, 1511, she gives birth to twins, the oldest a girl and the youngest a boy. They are Alexeia and Alexios.

1511: The fortunes of war continue to blow against the Plantagenets. Fate seems to smile on them when Leo Komnenos is ambushed near Bordeaux, and then frowns again when Leo proceeds to hack his way out. Despite the heavy losses to Leo’s column, it serves to bolster the Prince’s prestige as he demonstrated impeccable bravery in the melee. Six days later the garrison of Bordeaux surrenders to the Arletians after news arrives of the bungled ambush. To honor Leo, the new King of Arles, Charles II (his father died a year earlier), makes Leo’s eleven-year-old son Basileios one of his squires.

In the north, the situation is little better. Newcastle-upon-Tyne has fallen, and although logistics have stopped the Norwegian-Scottish advance short of York, their raids are ravaging northern England. Privateers are both sides continue to turn the Channel, Irish, and North Sea into a war zone, attacking each other and anyone else within reach. Five more Castilian carracks have been attacked, along with twenty Dutch vessels. Pride of place goes to the privateers operating out of Yarmouth, patronized by the Duke of Norfolk, which have, in addition to the usual Iberian, Italian, Hansa, and Scandinavian targets, seized three Roman carracks laden with silk, jewelry, and sugar. The hauls are enough to pay for the squadron’s expense for the next decade.

But Rhomania has not been entirely (admittedly mostly) blind to the piracy in the west. On May 4, four Barbary galleys attack a Roman vessel off Sardinia, surrounding her and closing to board. They are almost in range when her gun ports slam open and she delivers a double-shot broadside at point-blank range. One galley is literally blown out of the water, while the second is stormed by waves of marines wielding a new and deadly invention. It is called kyzikoi, matchlock handguns small enough to be held in one hand and named after Kyzikos, their city of origin (largely deserted in earlier years, it was reestablished by European refugees from the Smyrna War). The corsair ship is overwhelmed, the other two fleeing.

The ship is called the Moldy Wreck, named by its commander, Andreas Angelos. Rather discontented with playing second fiddle on the eastern frontier (hence his underwear prank), he had asked his father for a more independent assignment. Given a new, unnamed great dromon, fresh from the Imperial Arsenal, four hundred tons and twenty seven guns, his mission is to ply the trade routes from Sicily to Antwerp, killing any pirates of any nationality he finds.

Andreas Jr. faithfully carries out his orders, sinking another Barbary galley off Gibraltar, and forcing an English barque to cast off her two prizes (one Portuguese, one Castilian) near Galicia. But it is off Flanders when his most famous action occurs, the rescuing of a to-be princess.

Her name is Mary of Antwerp, the fifteen-year-old daughter of Reynaerd van Afsnee, the richest non-royal man in Christendom after Andronikos Plethon. Besides being the only child of such wealth, she is also considered one of the most beautiful women in Christendom. After months of negotiations, she is to be married to Crown Prince Arthur, the five-year-old eldest son of King Edward VII.

Reynaerd van Afsnee and his family have based their wealth for over a hundred and twenty years on trading contacts with Rhomania. Long-time trading partners of the Plethon family since before the War of the Five Emperors, that has enabled them to have first access to all high-quality Roman silk exported outside of the Mediterranean. That has not only made them supremely wealthy, but also done much to spur the rise of Antwerp, the silks’ port of disembarkation. By this point the van Afsnees have their fingers and agents in everything from the Neva to the Senegal. So at one stroke, Edward VII can get the greatest of the Dutch ports on his side, and draw on an absolutely huge financial network (the van Afsnee and Plethon-Medici commercial empires) for loans.

It is that wealth that compensates for her lack of nobility. The bullion content initially comes off as insulting, 100,000 florins of gold and sixty thousand of silver. But they are accompanied by 460,000 florins-worth of high-grade Roman silk and 70,000 florins-worth of Chinese. To that is added 80,000 florins-worth of Imperial silk, the finest quality of Roman silk, of the level worn by the Emperors themselves, forbidden by law to be exported outside of the Empire, on the grounds that the barbarians are not worthy of it. The final sweetener are the offer of six carracks plus ten thousand florins each for their outfitting as warships, to be delivered after the wedding.

Yet it is the loan offers that finally convince Edward. An immediate loan of 250,000 florins, with interest at half the current market rate, is provided in the dowry. Reynaerd’s Plethon friends, interested in marrying up possibly through the French-English royal family, offer a sweetener loan of another 75,000 florins in the dowry. Plus Reynaerd holds out the possibility of another loan of equal magnitude from himself, plus another 350,000 from the Antwerp burghers once the wedding occurs. Again the Plethon intervene, and based on their projections on the gathering Second Pepper Fleet (in which they are the second largest shareholders), offer an absolutely immense loan, one million florins, over fifteen times Edward’s revenues as King of England.

But an event of this magnitude cannot be hidden, and the value of the prize is immense. Off of the Flemish coast Mary’s transport is attacked by three English privateers.

The ship is well armed and manned, but the English know what and who is on board, and are willing to fight hard to get it. The tide is turning against the Dutch when a ship appears on the horizon, a full spread of sail out, bearing down on them at an unbelievable speed. The second volley from her great bow chasers dismast one of the English vessels. The Brabantines, holding out in the aft castle, launch a counterattack as the Moldy Wreck grapples the second English ship, the marines storming across with the cry of “For God and Emperor Andreas!”

Although Andreas Angelos is wounded in the left eye, the Englishmen take flight. The badly damaged carrack is escorted back to Antwerp, during which Andreas loses the eye, and torture of the prisoners reveals that the pirates were in the pay of the Duke of Norfolk, the most preeminent of the English grandees.

When they sail into Antwerp, the Romans are treated to a massive triumphal procession. The tale of the battle is immediately turned into a ballad, called Perseus of Rhomania, where Andreas is turned into a modern-day Perseus, Mary playing the role of Andromeda, today one of the most famous pieces of Dutch literature. Reynaerd, grateful for the rescue of his only child, gives the gold of the dowry to Andreas Angelos personally and divides the silver amongst his crew.

Andreas Angelos. Unique among the children of Andreas Komnenos, he is making quite a name for himself for his exploits at sea.

The engagement to Arthur is cut off, as Reynaerd is enraged over the assault on his daughter’s life by no one less than an English grandee and instead Mary marries recently-widowed King Charles I of Lotharingia for the same dowry, for which he had been negotiating. Three weeks after the marriage, it bears fruit when a combined Lotharingian-Dutch army annihilates Archduke Antoine at Utrecht. Participating in the battle are three companies of Hungarian hussars, part of an alliance arrangement between Charles and Andrew. The Emperor in the South (as he is known to distinguish him from Manfred) agrees to recognize full Lotharingian sovereignty in its pre-Cannae borders, in exchange for a twelve-year payment of tribute (used to pay for Hungarian garrisons in Bavaria).

Mary of Antwerp, Queen of Lotharingia, 1519. It is her life that is the origin of the phrase "Hell hath no fury like a woman betrayed".

1512: The situation for the Emperor in the North is improving, despite the defeat of his preeminent vassal in the west. The birth of a son by his Russian bride significantly strengthens the alliance with the Great Kingdom, as old Megas Rigas Nikolai quite likes the idea of a grandson as Holy Roman Emperor, to go with his nephew as Roman Emperor. To pave the way for any necessary intervention, a treaty is arranged with Vlachia whereby Russian troops will be allowed to march through Vlach territory, provided they respect all local laws and pay for all supplies.

One immediate benefit is that Sweden-Denmark dares not move against Manfred, now that he has withdrawn completely from Danish territory. King Charles II of Sweden is uncomfortable aware of how vulnerable his Finnish estates are to Russian incursions. And unlike a war with Rhomania, Lord Novgorod the Great would savor a conflict with Sweden. But Nikolai will not act without provocation, as his attention is fixed to the trans-Volga, where the Cossacks have been trouncing the Khanates of Sibir and the White Horde.

Andrew too is slowing down. With Germany muttering at best, he has had to rely greatly on Magyar troops and officials to keep his German territories in line, which only serves to further aggravate the princes. Manfred has been waging, thanks to the great print shops of Lubeck, a continuous propaganda war, harkening back to the days of the Ottonian Emperors and their war against the Magyar menace, exhorting ‘the German people to stand united behind their true Emperor, so that a new Lechfeld can be won, and Germania made safe, free and prosperous.’ Obviously something is working, for in August, an assassin makes an attempt on Andrew’s life, wounding although not killing him.

In these troubled times, it is hardly surprising that thoughts of the afterlife are never far from people’s mind. Saxony has been an oasis of calm for the past few years; the most powerful of the German states after Bavaria, its strength means both Manfred and Andrew must treat it with respect, even though it has been following a policy of de facto independence from either Emperor.

All that changes on September 14. On that day, Heinrich Bohm, a doctor of theology from the University of Prague, nails a list on the door of the Cathedral of the Blessed Virgin Mary (in OTL, the site of the Dresden Frauenkirche). It is a list of criticisms of Catholic theology and practice, strongly influenced by Hussite beliefs. An usual method to start an academic debate, what is special is that Bohm posts a copy in German next to the Latin original. He wants a bigger audience for the debate, as there is a vacancy on the Dresden university faculty, and Bohm wants the position.

The reaction is not exactly what Bohm expected. By September 17, there are at least two thousand copies of the 75 Criticisms circulating in the city. By the end of the month, they are in Bohemia and Bavaria. Heinrich is summoned to the court of the Saxon Duke Johannes V, but not for a condemnation; he wants to hear more. He is particularly interested in the arguments about how the secular power should be wielded only by secular rulers, namely the princes, and that in the secular sphere good Christians owe the same devotion and loyalty to their prince as would be due to the Pope in religious affairs.

The Saxon court on the other hand is horrified. Bohm’s criticisms in many cases flirt with heresy at best, but when the word ‘heresy’ is mentioned, the first thing that comes to mind is Avignon. There is fear that this is the vanguard of a heretical attack, with Hungary constituting the main wave. Their concerns are not helped when several squadrons of hussars skirt the Bohemian border, enforcing tax payments from the villages. At the same time, the Elbe, swelled by autumn rains, overflows its banks and floods several villages, along with a part of Dresden itself. Many think it is a sign from an angry God.

So on November 12, the conspirators, a mix of clergy, pious nobles, and Johannes’ sister Amalie strike. Duke Johannes V is seized in the coup, but Heinrich Bohm manages to flee the city, eventually making his way to Gdansk. From there he takes a ship to Antwerp, and from there on to England. Although the troublesome scholar is gone, none of the conspirators are quite sure what to do next. Andrew is clearly massing on the border, thinking that with Saxony in an uproar, now is the time to strike. Then on December 1, Johannes dies under mysterious circumstances (many believe poisoned by Amalie).

Without even a puppet duke, only a council of confused old men and a women to lead a duchy filled with agitated people, Saxony seems right for the picking. So the council of Saxony turns to the one leader who has stood against heresy and won, his most Catholic Majesty, Emperor Manfred. On Christmas Day, at the very cathedral where Bohm nailed his criticisms, he is crowned Duke of Saxony. Although he appoints Amalie as his viceroy, and pledges to respect the rights and privileges of the Saxon nobility, the importance of the coronation for the history of Germany cannot be understated. For in Manfred are legally united the domains of Bavaria, Tyrol, Schleswig, Holstein, Brandenburg, and Saxony (although the first two are currently in Hungarian hands).

The Saxons do what they do not for the benefit of Saxony, or Germany, but for the beleaguered Catholic faith. They have no doubt that they have done for the right thing, for on December 31 the news arrives. Andrew of Hungary is dead, slain by infection from his assassination wound. But to the Saxons, the answer is that God has smiled on them for the faith, and delivered them from their enemy.

The Hungarians mourn their fallen Emperor. All of Buda goes into mourning, for his concern for the poor and his military victories abroad ensure that he is loved by all of Magyar society. Fifty thousand attend the procession as his body is carried into Buda, to be buried in a mausoleum next to that of Andrew the Warrior King. His son Stephen ascends the throne without any difficulty, pledging to finish the work his father has left undone. There is no doubt that Stephen will have the wholehearted support of the Hungarian people in that task, for he is the firstborn son of the most beloved of the Arpad kings.

1513: In Buda Stephen is crowned Holy Roman Emperor, in flagrant disregard of all the customs of the Reich, and without the approval of any of the Electors. His first action is to the north, where the fervor of fanatical Catholics has turned into violence against the Hussites of Bohemia, Saxony, and Pomerania. The hard-pressed heretics turn in desperation to Stephen, who responds vigorously and dispels the attacks.

However the whole operation does much to solidify the strengthening view in northern Germany that the war against the Magyar Emperors is a war against heresy. The new Pope in Hamburg (the place of exile after the fall of Mainz) Leo X fully supports the view, allowing Manfred to tax a fifth of clerical income in his domains, and ordering sees from outside Germany to commit to the fund. This causes an immediate spat with Edward VII, who is also fighting heretics but was never granted a similar privilege, because ‘my heretics are not threatening the person of the Holy Father’.

His position in northern France seems to be stabilizing, despite the failure of the Antwerp betrothal. The Arletian offensive, after the fall of Aquitaine, managed a lightning rush that moved the border to the Loire valley, but has slowed down significantly due in large part to the stout resistance of Tours and Orleans. In the lands of the langue d’oeil the Arletians can count on far less turncoats. Most of the fighting is concentrated in the Loire valley, and although the semi-professional Arletian lances give better then they get, sheer attrition is starting to show in France-England’s favor.

This is helped somewhat by Leo’s conduct. After the Bordeaux ambush, he has commanded seven different engagements and won them all, but through courage and ferocity rather than skill, piling up a horrendous Plantagenet body count, but also quite a high Arletian one. Plus his refusal to rein in his troops post-battle ‘antics’ is further complicating Arletian efforts to win over the region. Reminders that King Charles of Arles is a direct male descendant of Francis ‘the Butcher’ whisper in the wind.

That said, Arletian policy in the lands of the langue d’oeil is not the most conducive to earning the love of the French people. That Arles has been heavily influenced by Rhomania, there can be no doubt. At any given day, there are at least a thousand Roman merchants in the harbors of Provence. The centralized administration of Arles’ largest trading partner is the envy of the court in Marseille, and Charles is attempting to establish it in his new conquests. Provencal is to be the language of the courts and laws, which are to be organized on Provencal custom, instead of local tradition. The exception to this rule is Aquitaine, for Gascon custom is viewed as ‘close enough’ to Provencal to pass muster.

The taille is levied on all Frenchmen, including the local nobility and clergy, and breaking with French tradition, Charles sets the taille at a standard and very high rate and then leaves it there, without the usual annual adjustment. Naturally this imposition of an extraordinary tax now being treated like a regular occurrence angers many, particularly the nobility of France (Charles is intent on making France pay for the war, with the Arletian and Gascon tailles set at two-thirds the French rate). The war in Germany also exerts some influence on the war in France, as the clergy emphasize the heretical nature of the Arletians, plus the influence of the heretic Romans on Arletian policy, with some radical peasants and townsmen taking up the cry ‘taxation is heresy’.

Although the French are finding Marseille more burdensome than Calais, that does little to help Edward VII. In July the hammer blow falls. Lotharingia declares war on the third day of the month. Although the actions of Mary of Antwerp play a significant role (supposedly she refused to make love with her husband the king until he made war on England) it is also an easy way to gain the support of the long-suffering Dutch. Nine days later Castile declares war as well, contributing ten thousand men and thirty ships.

In the Mediterranean, Andreas Angelos is at it again. Off the African coast, he spots a Barbary galley bearing down on a Roman carrack. Chasing it off, he pursues, grappling and boarding the corsair within range of the port batteries of Algiers itself, the greatest of the Barbary cities. Two more galleys sally to support their Muslim brothers; the first is blown apart by the Moldy Wreck’s bow chasers, at which point the second withdraws.

Nonetheless, his would-be triumphal return to Constantinople is marred. The day before he arrives, his uncle Andronikos Angelos, dies of old age. Emperor Andreas returns to the capital for the funeral, for despite the row over Andreas Angelos’ parentage, the Master of Sieges has nonetheless been Andreas’ bodyguard, companion, and friend for sixty years.

While the west is at war, Russia is calm and peaceful, save for the low-level rumble along the eastern frontier. In May, an university is founded at Draconovsk, the largest city in Scythia (OTL Ukraine) with twenty thousand inhabitants. It is the second in Russia, and like the one at Novgorod it is a near copy of a Roman institution. But of the faculty, a quarter are Romans, another quarter Russians educated in the Empire, and half from the University of Novgorod.

Although the importance and number of Russian intellectuals are rising, Roman scholars still retain much importance in the Great Kingdom, particularly in the Novgorodian sphere (due to the division of Russia into Novgorod, Lithuania, Pronsk, and Scythia all of which have significant local autonomy, the Great Kingdom of the Rus is often classified as a ‘federal empire’). Many Roman university students are hired as tutors for Russian upper-class children, since speaking Greek is considered a sign of high culture.

At the same time, the intellectual current generated by the two universities is challenged by a new movements, the Monks-Beyond-The-Volga. As peasant emigration is concentrated south towards Scythia, the Orthodox church has taken the lead in developing the trans-Volga, where on paper Russia rules, but reality is a different story. It is a harsh, wild existence, living on the fringes of the known world, carving a place in the wilderness, both physically and spiritually. The monks are mostly Russian, although about 10% are Greeks, followers of a strong mystical Orthodox tradition heavily influenced by hesychasm and extremely popular amongst their Cossack neighbors.

Many of the monks also accompany the Cossacks on their raids against the Tatars to the east and south. Sibir, the Timurid Empire, and the White Horde all suffer from the attacks of the disciplined Cossack hosts, divided into polki (regiments) five hundred strong, each one with at least one battery of artillery. The White Horde suffers the most from the annual incursions, as it lacks the strength of the Timurid Empire or the distance of Sibir.

1514: Deva Raya II has been quite annoyed at the delay in the Second Pepper Fleet. Every year since the First Pepper Fleet, a few Roman vessels, along with a couple of Ethiopians, have ridden the monsoon winds, but these are traders, interested in spices, not warfare. His mood substantially improves when the Second Pepper Fleet sails in Alappuzha.

It is twenty two ships strong, including thirteen great dromons and two purxiphoi, along with fifteen hundred Roman soldiers. The largest of the great dromons, a five hundred tonner with thirty two guns, is the Hikanatos, commanded by Andreas Angelos. His father had had him transferred to the Indian Ocean during the winter, while his old ship continued its anti-piracy patrol in the west.

India as well as Rhomania is astir at the news from Persia. Aside from a handful of raids that have since died down, the Ottomans and Timurids are not fighting each other, allowing the Turks to concentrate their energies on the Shah, who is no more. With the fall of Damghan all of the former realms of the Shahanshah are either in Ottoman hands, or that of the Emirs of Yazd or Tabas. Their combined armies are resoundingly defeated at Meybod, although that victory is somewhat marred by a smaller defeat at Khorasani hands near Bafq. But the battle of Bafq does not stop the massive ceremony staged in Baghdad.

Suleiman is officially proclaimed Shahanshah, Sultan of E-raq and E-ran, and Caliph. The last title is taken on the grounds that the Ottoman Empire, as the most powerful Muslim state in the world, bears the responsibility for defending the Muslim faith against her enemies. This is especially important as in Baghdad’s eyes, the Hedjaz is a Roman vassal. Legally it is not, as Sharif Ali ibn Saud has no treaty obligations with Constantinople but as a gesture of goodwill sends a biannual shipment of three Arabian stallions to the Roman capital.

Suleiman is willing to practice what he preaches, and to aid the Muslims of Gujarat and Maharashtra he dispatches thirty galleys, virtually the entirely of the Ottoman fleet, to Surat to reinforce the gathering Muslim armada. Andreas Angelos had been dispatched to Kolkata, where he successfully negotiated with the Bihari king for a trade quarter in Kolkata with similar rights to the ones held by Romans in Vijayanagar. But he returns in time for the planned offensive, the Roman fleet providing naval support for the Vijayanagara army.

The Hindu Emperor can muster over fifty thousand men, forty cannon (although of a very poor quality compared to Roman artillery), and three hundred elephants, but without a fleet he stands little chance of seizing the port cities. Everyone involves knows that the contest will be decided at sea. On August 1, the fleets meet at Ratnagiri.

The Romans muster fifteen warships, joined by three Ethiopian vessels. The government in Gonder has negotiated successfully for trading quarters in Alappuzha, and made an arrangement with Rhomania that in exchange for military support in India they shall receive quarters in Surat and Kozhikode once they are Roman. Just before the battle, the Romans and Ethiopians are joined by an unexpected defector, the commander of the Ottoman contingent.

He is Basileios Komnenos, son of Anastasia Komnena and twin brother to Konstantinos Komnenos (both take their far more prestigious maternal family name). His time in Ottoman service has not been nearly as beneficial as his brother’s. Largely ostracized from the Ottoman court due to his refusal to convert to Islam (there were rumors in Constantinople that he had converted, but they were false), he also expected to be appointed governor of Hormuz. He only had commanded the fleet that starved the great port into submission, but the city had been given to an Arab from Basra. The fact that his star has risen this far is Sultan Suleiman’s desire to keep his best friend Konstantinos happy.

But Basileios has had enough of E-raq and E-ran. In exchange for asylum in Rhomania, he provides a complete order of battle for the Muslim fleet. They number a hundred and forty strong.

The battle begins at dawn, and is a slaughter. Only the Ottoman galleys can match the Roman and Ethiopian artillery in quality, and the two purxiphoi alone mount as many pieces as all thirty galleys combined. Most of the Indian attacks are blown out of the water before they can press home their attacks, although the sheer number of vessels mean the less maneuverable Roman and Ethiopian purxiphoi are grappled and boarded. But even there the odds are against them, for their Orthodox opponents are far taller than them.

The battle lasts all day and ends in a crushing Roman-Ethiopian victory. Both Basileios Komnenos and Andreas Angelos are the heroes of the day. The former identifies the flagship of the Ottoman contingent and leads the boarding party that seizes it, personally cutting down the ship’s pilot. Andreas Angelos meanwhile tracks down the ship carrying the fleet’s pay and takes it and its cargo.

The battle is nothing less than a disaster for the Muslims of India. With the sea in Orthodox hands, their re-conquest by Vijayanagar is only a matter of time and Deva Raya II sets to it with a vengeance. At the same time he dispatches waves of Rajput cavalry, descendents of emigrants, north of the Narmada river to pillage the Delhi Sultanate so there will be no aid from that quarter.