1580

Part III: The Son Also Rises

The First years

The entire year that passed between Shingen’s death and Katsuyori’s departure from Kofu Castle in 1580 was spent in what could be considered a rest in the expansionist momentum built by the Takeda in the past five years.

Takeda Katsuyori was not the great state builder and administrator Shingen was, and he was surely not expected to adequately succeed in the enterprise that was to succeed the great Shingen, but the regent was nonetheless able to surprise his detractors and rise to the challenge of managing the large domains of the Takeda.

The economic and administrative system built by Shingen between the 1540s and 1578 was largely kept and even expanded, as the growth of the domains and the redistribution of the conquered lands between the Takeda loyalists and retainers, especially the division of the large and rich province of Echigo, forced the system to be reorganized and the Takeda Domain to be administrated in a different manner. The more loyal retainers, that is the 24 generals, were the most benefited, especially Yamagata Masakage, Baba Nobufusa and Obata Masamori, who gained the largest extensions in the northern province of Echigo.

The new government saw a rapid decentralization between 1579 and 1585, a tendency that would be reverted in the 1580s but that in the early years of Katsuyori’s government allowed the daimyo to concentrate on important issues other than the administration of his vast realm.

The Takeda lands prospered economically and politically, as the most powerful domain in the Empire of Japan grew in power and influence. This growth was accompanied by a growth in the power of the lords under the Takeda, not only the Generals such as the Yamagata, the Obata and the Sanada, but also some of the sakikata-shu (the group of vanquished enemies), such as the Christian Daimyo of Yamato, Takayama Ukon, and the vassal daimyos such as the Asai and the Asakura.

Religious freedom in the Takeda domain continued to be restricted as the Ikko-Ikki presence in the Takeda lands remained limited, a policy that Shingen himself had started and that he continued even after his alliance with the Ikko-Ikki against Oda Nobunaga.

The rise of Christianity in the western provinces, the maintenance of the Buddhist sects in the east and the growth of the Jodo Shinshu faith, the sect of the Ikko-Ikki, showed that the religious structure within the Takeda Domain had vastly changed from the old mono-religious nature of Shingen’s Buddhist fanaticism.

The reorganization of the lands, the administration of the conquered territories in the east and the overseeing of infrastructure projects, as well as the relocation of the Uesugi from Echigo to the Kanto and the destruction of much of the old Hojo political apparatus in their former domains; all of these tasks took much of the time of Katsuyori between 1578 and 1580, proving that the son had inherited the father’s administrative skills, as well as many of his old military abilities.

But it would be the year of 1580 the one to definitely cement Katsuyori’s place and position as the heir of Takeda Shingen, when he finally assembled a force to return to Kyoto and depose the last of the Ashikaga Shogun, Ashikaga Yoshiaki, the man that had plotted to kill his father and destroy the Takeda clan by rallying the Uesugi and the Hojo against them.

On March of 1580, Takeda Katsuyori was joined by 10 of the original 24 generals of Takeda Shingen as well as a force of 30,000 men, and began his march from the eastern capital of Kofu to the Imperial capital of Kyoto.

Seven years later

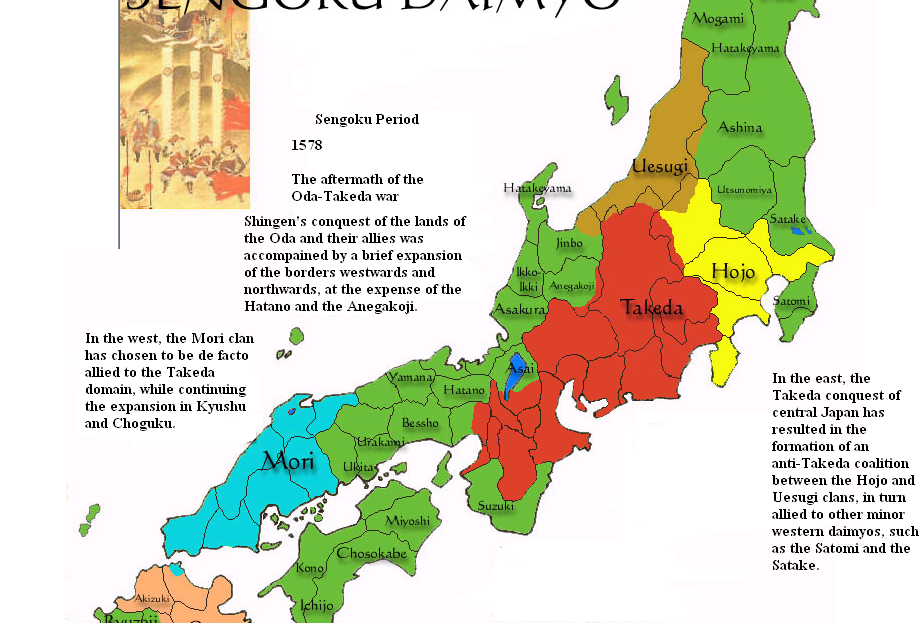

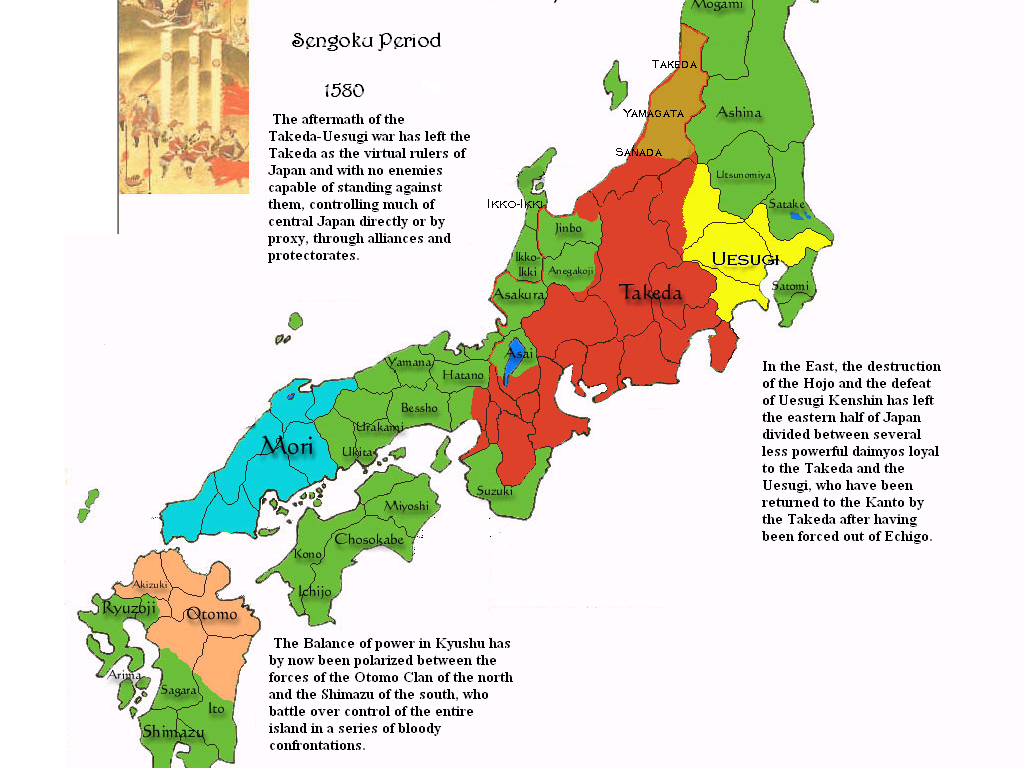

The balance of power in 1580 had changed greatly since Takeda Shingen decided to wage war upon the Oda and the Tokugawa on the behalf of the Ashigaka Shogun.

In 1573, the Empire of Japan was dominated by dozens of small daimyos with small to medium domains while the largest domains within the nation were under the greatest clans of the Empire: the Hojo of Kanto, the Takeda of Kai, the Otomo of Bungo, the Uesugi of Echigo, the Tokugawa of Totomi, the Mori of Bunzen and the rising Oda Nobunaga of Owari. Seven years later, Nobunaga, Ieyasu, Kenshin, Ujiyasu and Shingen were dead and only 3 of the seven great clans and three great lords were still standing strong: Otomo Sorin in Bungo, Mori Terumoto in Bunzen and Takeda Katsuyori, who’s domain extended from Kyoto to Kofu.

And apart from the three great surviving Daimyo clans (five if the relocated Uesugi of the Kanto and the then rising Shimazu of Satsuma were to be counted), another regional power was rising in the form of the Ikko-Ikki, the fanatical followers of the teachings of Jodo Shinshu Buddhism. Prior to 1573 and the Oda-Takeda war, they had come to dominated vast territories, including the rich province of Kaga, and were involved in a bloody war with the Oda of Owari as the rising daimyo besieged the fortresses of Nagashima and Hongan-Ji.

Following the war, not only did their power and influence grow as their cities were saved and their ranks swelled by thousands of new followers joining, but their geographical base was also augmented.

The death of the Hakateyama lord of Noto province, Hakateyama Yoshinori, in 1577, in the midst of the Uesugi-Takeda war, ignited a civil war in the province between the successors and retainers of the deceased daimyo, thus giving the Ikko-Ikki the perfect opportunity to invade and overrun the province.

The retainer that had killed Yoshinori, Cho Shigetsura, was amongst the killed at the siege of Anamizu Castle in late 1577. By the spring of 1578 the Ikko-Ikki had completed their conquest of the province and their purging of the old feudal system in the region had begun in earnest, as well as the spreading of the teachings of Jodo Shinshu.