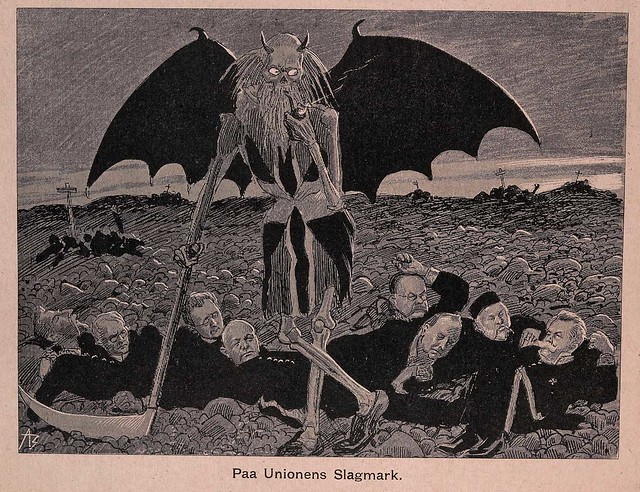

Dissolution Crisis of 1905, Part XVII: Kusteskadern

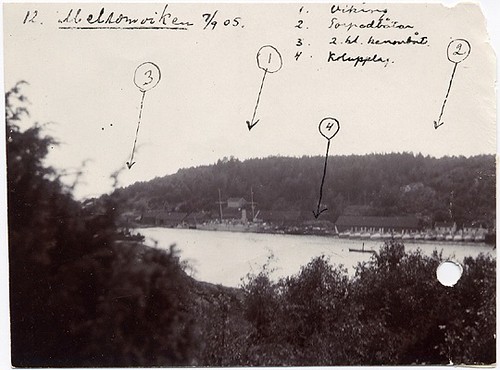

The way the Royal Swedish Navy rose to prominence at the culmination point of the Norwegian Secession crisis was a showcase example of the growing power of navalism in European diplomacy and war planning. Gone were the days of the Crimean War, when the antiquated and small Swedish navy had been happy to lie low behind the mighty Anglo-British fleet, allowing foreign warships to use most of the Swedish Baltic naval bases, especially Fårösund off Gotland, at will. The slight Russians had taken from the conduct of their formally neutral neighbour had not been missed in Stockholm, and after that time Swedish naval power had experienced a lot of development. While Norway had built up her new navy during the last decade, at the same time the Swedish defense spending had nearly doubled, from kroner 28 million a year in 1890 to 58 million in 1901. These increases dwarfed the percentage-wise similar Norwegian efforts, from 9 million in 1890 to 20 million in 1901. For on the Swedish side, at least, much of the rationale for increased defense spending had been originally derived from a perception of a growing threat from the East. During the last few decades Sweden had been preparing her defenses against the Russian Baltic Fleet, alarmed by the Russian naval expansion and the determined Russification program in the Grand Duchy of Finland. The realization that Norway had been in the meantime more less openly preparing for a confrontation against her Union partner had created a sense of deep bitterness in the Swedish military elite. The animosity towards Norway was evident in the fact that the Swedish naval officer corps eagerly begun to prepare for a possible "naval demonstration" against Norway as soon as Oscar II had been legally overthrown as a King of Norway. Before summer 1905 there had been no naval plans against Norway. But after months of intense staff work, the plan that had emerged from the drawing boards just when the Karlstad negotiations were just about to begin was certainly impressive. While bold and ambitious, it was also considered to be a realistic assessment of the general situation. The main aim of the plan was to maximize Swedish strengths against the weaknesses of Norwegian defence. And it was reinforced with fresh intelligence. The Swedish naval spy had been able to take photographs and draw sketched map of the Melsomvik naval base and the anchored Norwegian fleet before it put out to sea on 9th September.

In essense the Swedish plan was a true combined-arms operation. The capital ships of the Swedish

Kusteskadern, the Coastal Fleet, would be relocated within striking distance of Norwegian waters, and tasked prepare for an attack against the Norwegian naval base at Melsomvik, on the West bank of the Kristianiafjord. If the negotiations at Karlstadt would fail to achieve the results required by Stockholm, the Swedish fleet would be in full readiness to commence the attack. The Swedish admirals were convinced that a crushing naval defeat would force the Norwegians to concede defeat and return to the negotiating table. Considering the numerical strength of the two sides, the optimism of the Swedish Admiralty was well-founded, at least when considering the military prospects of a Swedish naval invasion. Against the Norwegian fleet of three modern armored ships and 18 torpedo boats the Swedish navy could assemble a force of eight modern and three old armored ships, five modern light cruisers with a displacement of 800, 23 modern torpedo boats and a new feat of naval engineering - a brand-new submarine,

HMS Hajen, built as a Swedish version of the US Holland-type.

The oldest trio of the Swedish armored ships -

Svea,

Göta and

Thule - had been build between 1885 and 1893, and had just recently finished an extensive refit and modernization program. With two-shaft reciprocating engines they were capable of a top speed of 14 knots, and their main armament consisted of two 254mm guns in a twin tower and 4 x 152cm guns on side casemates.Their new main guns, the 210mm M98s, were installed on two single-gun turrets, supported by seven single-turret 152mm M98 quick-firing guns and 11 57mm M89B anti-torpedoboat guns. The main guns had armored turret protected by 190 - 140mm Krupp nickel steel, and the barbette had 190mm protection.

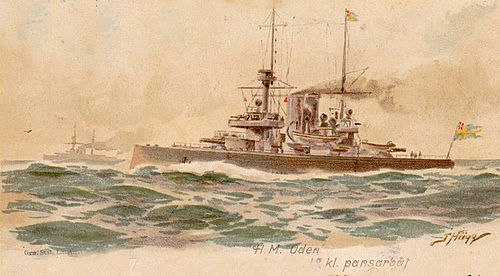

These ships had been followed by the next three

pansarbåtar-type ships constructed between 1896 and 1898:

Oden,

Thor and

Niord. Constructed with the new Harvey armour, they had new triple expansion reciprocating engines, and were capable of top speed of 15 knots. Armament consisted of two 254mm main guns located to the front and rear towers, and four 120mm cannons located to the side casemates.

HSwMS Dristigheten was a single-ship prototype class, constructed as a modified Oden-class vessel with the new main armament layout of two 210mm Bofors M/98 quick-firing cannons in single-gun turrets at front and rear decks, and a secondary armament of six quick-firing 152mm Bofors M/98 guns in side casemates, supported by additional anti-torpedo boat armament of ten light 57mm Ssk. M/89B guns. This arsenal made her the first ship in the Swedish navy armed exclusively with quick-firing guns, supported by two underwater 457mm M/99 torpedo tubes. Her new armor layout gave her protection of 200mm of Harvey-type nickel steel belt for the sides, and a deck thickness of 25mm. The propulsion consisted of reciprocating steam engines with new water-tube boilers, and the top speed of the new design was 16,8 knots, making her the fastest of the Swedish armored ships.

The next generation, the Äran-class, was based on the lessons learned from the Dristingheten-class and consisted of four ships -

Äran,

Wasa,

Tapperheten and

Manligheten - constructed between 1899 and 1904. They used the same new design where the main artillery armament, two 210mm Bofors M/98 cannons (which despite the lower caliber had greater range and firing rate than the older 254mm guns), were located to single-cannon towers at back and rear decks of the ship. Secondary armament was also similar, and consisted of six quick-firing 152mm Bofors cannons, now placed on side turrets instead of casemates. The new 6,500hp (4,800kW) two-shaft engines were capable of providing the ships with a top speed of 16,5 knots.

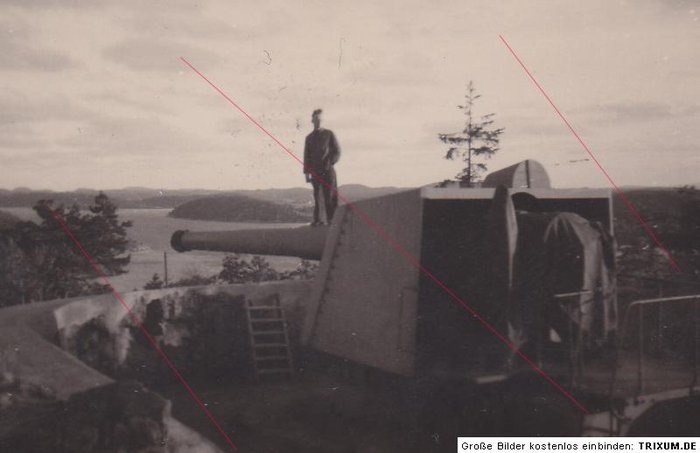

To make sure that the Swedish warfleet would be able to deliver the desired crushing blow to the Norwegian fleet, the Admiralty insisted that the attack should also have a land component. As long as they controlled the narrow approaches of the Kristianiafjord, the Norwegian fleet could choose where and when it wanted to do battle. In the plan the task of forcing them to sail forth was assigned to the so-called

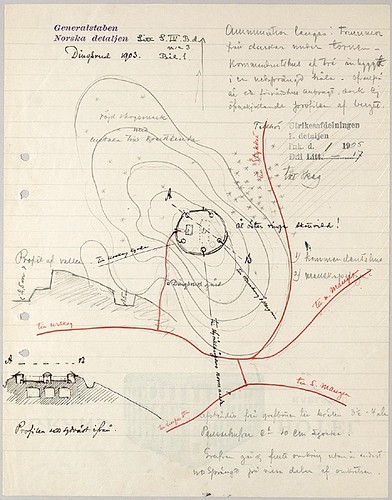

Bohusdetachementet, a regional command under Colonel Olof Malm of Bohuslän Regiment based at Backamo, south of Ljungskile. Malm had his headquarters in Uddevalla Town Hall, and the Grenadier units stationed to Vaxholm and Karlskrona were also under his command. The plan called this troops troops to embark the Kusteskadern capital ships and torpedo boats in the vicinity of Resö, few kilometers south of Stromstad, so that they could be shipped westwards and landed on the beaches near the naval base of Melsomvik.

In the next phase of the attack more infantry and the heavy artillery of the invasion force would be transported with large barges from Stromstad, and brought ashore at Tjøme and on the east side of Nøtterøy. In total a force of seven battalions of infantry and six coastal artillery batteries with a total of 12 guns and eight howitzers would establish a beachhead here, support Swedish minesweeping operations to clear Vrengen of naval mines, while the land troops at Nøtterøy would work their way to the top of Vardås and start an artillery siege of Håøya. The harassing artillery fire to their base would force the Norwegian Navy to evacuate Melsomvik. And sailing out from narrow Vestfjord, they would face a superior Swedish fleet ready and waiting.

The Swedish fleet and the Army units earmarked for the operation were in full alert in early September, and their relocation from Gothenburg to nortward positions withing spitting distance of Norwegian territorial waters was purposefully done in a visible and aggressive manner. By early September they were as ready as they would ever be. If the government gave the order, the Kusteskadern would sail northward with full steam - and war in the North would follow in its wake.