Hnau

Banned

Most recent discussion thread (with link to the original)

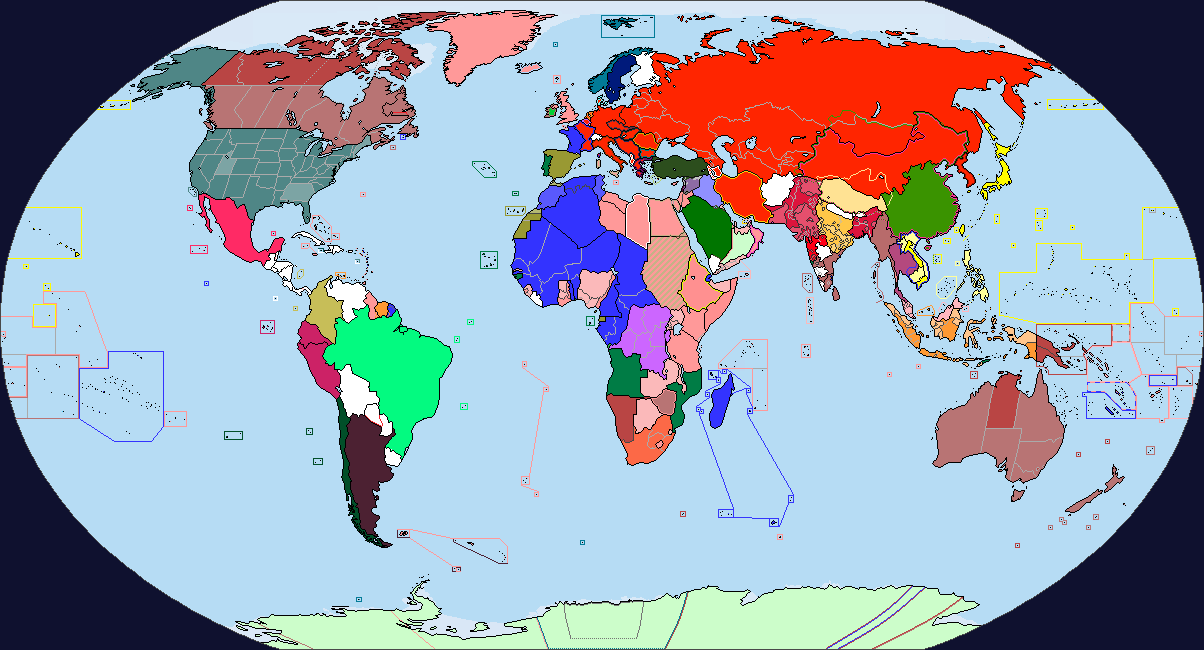

Post-war borders, 1952 by Zek Sora

The Falcon Cannot Hear: The Second American Civil War 1937-1944

by Ephraim Ben Raphael

"Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand."

- The Second Coming, W.B. Yeats

Prologue - 1929

In September 1929 the United States of America was at the top its game. Europe, devastated by the First World War, was still climbing out of revolutionary turmoil of the late ‘Teens and early Twenties. National economies worldwide were wracked by uncertainty and instability, feeding simmering unrest. But in America business leaders spoke of the New Era, of the map to a New El Dorado that would allow for an ever-expanding economy, full employment, and the elimination of poverty. They scoffed at the communists in Russia with their state planned economy, America was proof that capitalism worked. The country had no enemies, Great Britain- the world’s only superpower- was a staunch ally and Lloyd’s of London offered 500-to-1 odds against any invasion of the United States. The general mood was one of optimism, complacency, and comfort. Yet within a decade America would be broken against itself, foreign troops would march down its boulevards and half-a-million Americans would die in the worst genocide to be witnessed by the New World since the annihilation of its native peoples.

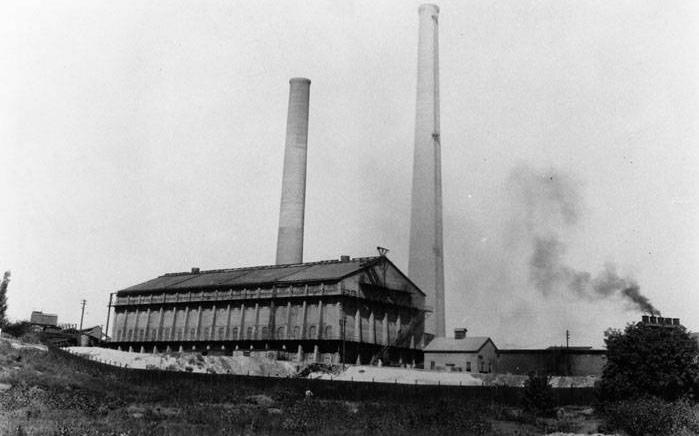

A New York parts factory in 1928, at the time American industry led the world.

How could this happen? The seeds of destruction did not come from abroad, but from within the nation. As Abraham Lincoln said in 1838 “if destruction be our lot we must ourselves be its author and finisher”. It was the false underpinnings of the New Era that brought the house of cards down.

In the aftermath of the World War the techniques of mass production combined to increase the efficiency of per man-hour by over 40%. This enormous output of goods clearly required a commensurate increase in purchasing power- that is to say higher wages. But over the 1920’s income failed to keep pace with production. In the golden year of 1929 Brookings economists calculated that to supply the barest necessities a family would need an income of $2,000 a year- more than what 60% of American families were earning. The general mood of the time however, was such that overproduction was no problem, the sense was that “a good salesman can sell anything.” This meant that customers of limited means were encouraged to buy products anyhow via a massive overextension of their credit. As zealous commercial travelers sold anything and

everything to people who lacked the means to pay for it, the rich (and many who weren’t rich) speculated overwhelmingly in stocks. Arthur A. Robertson watched aghast as investors bought $500,000 of stock with only $500 down. For eight or ten dollars the smart investor could get one hundred dollars worth of stock on margin. As a consequence the slightest shake-up became a calamity as people lacked the money to cover their investments.

Then on October 29, 1929 it came time to pay the piper.

A mob outside the New York Stock Exchange on October, 29, 1929.

The bottom fell out of the market and stock prices plunged, going down to no more than a few percent of their former value. In one day alone the New York Stock Exchange lost between eight and nine billion dollars. That afternoon a group of New York bankers succeeded in temporarily halting the plunge, but confidence had already leaked out of the market. Five days later the panic began again and this time there was nothing anyone could do to stop it. “There has been a little distress selling on the Stock Exchange,” Thomas Lamont, Secretary of Commerce, commented in a truly remarkable display of understatement, “but conditions are still sound.” He was whistling in the dark, with few interruptions stocks would continue to fall for the next eight years.

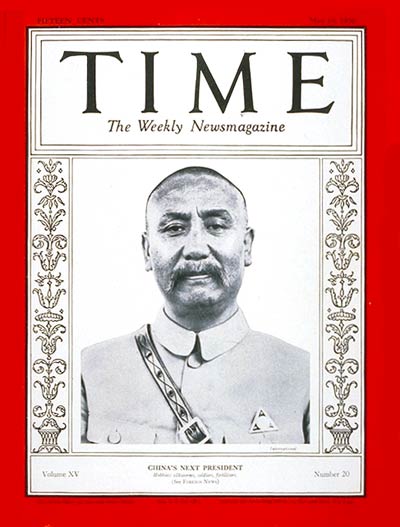

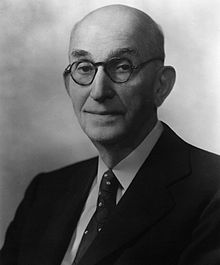

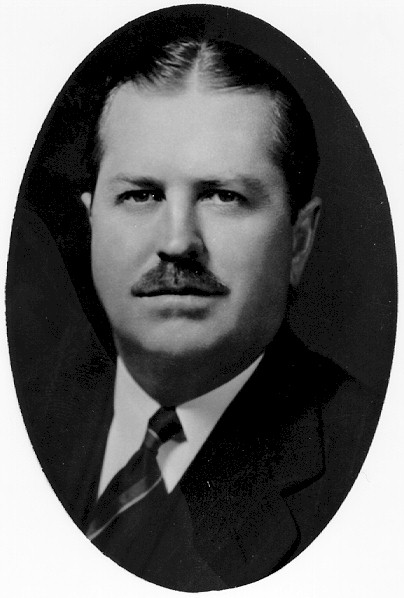

Thomas Lamont on the cover of Time Magazine, November 1929.

Unemployed workers warming themselves over trashcan fire.

It was in the growing masses of the unemployed that the seeds of radicalism began to take hold. In 1930 the Unemployed Councils of the USA (UCU) was first organized by the American Communist Party, then a tiny organization with about 10,000 members. Similar to the soviets of unemployed workers that emerged during the 1905 Russian Revolution, the UCU was a loosely organized body based around neighborhood councils composed of alienated and disillusioned unemployed. Little co-operation existed between respective UCU councils, and in fact most of the membership had not much interest in communism. Demanding public works, relief, and state aid, the UCU was often little more than an expression of American progressive thought. However, communist organizers were very active in the movement and they were able to present their teachings for the first time to a large number of Americans- clearing ground for the expansion of the party.

A meeting of the St. Louis Unemployment Council. Note the multiracial nature of the membership.

On March 6, 1930 the “International Struggle against Worldwide Unemployment” was called by the Communist International. Across the United States some 100,000- 200,000 members of the UCU turned out to protest calling for “Work or Wages” and demanding that President Hoover do something to address the issue of unemployment. Law enforcement cracked down on the organization, arresting many of its leaders including William Z. Foster, but the diffuse nature of the UCU’s structure meant that the government response helped the councils more than it hurt them. The free publicity caused Unemployment Councils to swell, and although the Communist Party would attempt to establish a more rigid hierarchy for the councils later that year they were never truly able to control their creation.

From left to right; William Z. Foster, Robert Minor, and Israel Amter. The three communists and leaders of the UCU being arrested on March 6, 1930 for connection to the Unemployment Day Protests.

President Hoover making a radio address.

His election slogan in 1928 had been “A chicken in every pot and two cars in every garage”.

The American people meanwhile were not unaware of their commander-in-chief’s apathy, and they castigate him for it. The junkyard shanty towns that sprang up across the country were called “Hoovervilles”, the unemployed carried sacks of frayed belongings known as “Hoover bags”. The rural poor sawed off the fronts of broken-down flivvers, attached scrawny mules, and called the result “Hooverchariots”. The President tried to have the name changed to “Depression chariots” but no one bought it. “Hoover blankets” were old newspapers the homeless wrapped around themselves for warmth. “Hoover flags” were pockets turned inside out. “Hoover hogs” the jackrabbits hungry farmers caught for food. One popular joke of the time was to claim that Hoover asked Secretary Mellon for a nickel to telephone a friend and was told “Here’s a dime, phone both of them.”

The President explained his belief that the function of government was to “bring about a condition of affairs to the beneficial development of private enterprise”, adding that the only “moral” way out of the Depression was self-help; the people should find inspiration in the devotion of “great manufacturers, our railways, utilities, business houses, and public officials.” Since by this point the greater part of the people believed that the great manufacturers were a bunch of crooks this went over like a lead balloon. Hoover was a great advocate of conventional wisdom, he held the gold standard to be sacred even though eighteen nations lead by Great Britain had already abandoned it. He was convinced that a balanced budget was “the most essential factor to economic recovery”- despite the fact that by 1932 he had run the budget 4 billion dollars into the red. When he was at last convinced to do something about the Depression (whose name he himself had coined, it sounded less severe than “Panic”) he created the Reconstruction Finance Corporation to prop up sagging banks, and agreed to spend twenty-five million dollars on feed for farm animals on the condition that a bill authorizing one hundred and twenty thousand dollars for hungry people be tabled. The RFC promptly loaned 90 million dollars to the Central Republic Bank and Trust Company of Chicago of which the RFC chairman, Charles G. Dawes (former vice-president of the United States), was an officer, and a mere 30 million to state governments for unemployment relief. People called it “a breadline for big business”, which in a sense it was.

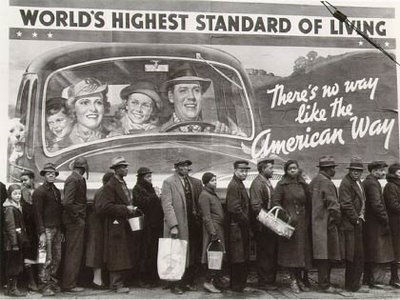

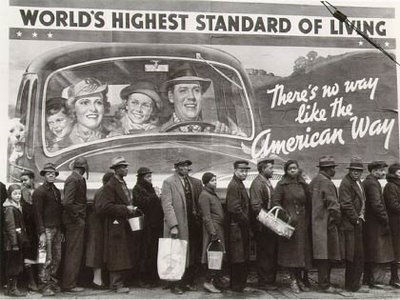

The National Association of Manufacturers put up murals like these in major American cities as part of their campaign to support the President and discourage liberal opposition.

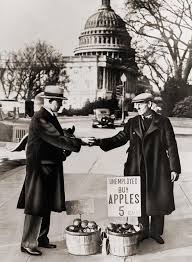

Still Hoover persisted in his views, unwilling to acknowledge that the country was truly in trouble. In December 1929 he declared that “conditions are fundamentally sound”. Three months later he said that the worst would be over in sixty days; at the end of May he predicted the economy would be back to normal by autumn; in June the market broke sharply, yet he told a delegation which came to plead for a public works project, “Gentlemen, you have come sixty days too late. The Depression is over.” On December 2, 1930 the President informed the lame-duck Republican congress that “the fundamental strength of the economy is unimpaired.” About the same time the International Apple Shipper Association decided to unload its surplus of apples by selling them on credit to jobless men for resale at a nickel each. Overnight the street corners became crowded with shivering apple salesmen. When asked about them, Hoover replied, “Many people have left their jobs for the more profitable one of selling apples.” When reporters’ questions turned to hunger he dismissed the problem, saying that “Nobody is actually starving. The hoboes for example, are better fed than they ever have been. One hobo in New York got ten meals in one day.” This when the New York City Welfare Council was reporting 110 (mostly children) dead of malnutrition.

A Washington, D.C. Apple Salesman.

On the streets of New York children sang;

Mellon pulled the whistle

Hoover rang the bell

Wall Street gave the signal

And the country went to hell.

Going into the year 1932 and the coming election Hoover was the subject of biting criticism and ridicule, nevertheless he hung on tightly to his optimism. Surely the hardworking American people would prefer a President who believed in the value of self-reliance? The economy had been bad for more than two years by that point and he was confident that it had to turn around sooner or later- why not in an election year? Meanwhile in the streets and crowded Hoovervilles the situation just kept on getting worse and worse.

Washington Under Siege- 1932

In January of 1932 a former army chaplain named James Renshaw Cox led a march of 25,000 unemployed Pennsylvanians to Washington, D.C. Supported by numerous notables including Pennsylvania governor Gifford Pinchot (a Republican), “Cox’s Army” was quickly broken up and dispersed. An embarrassed Hoover ordered a criminal investigation into how Cox was able to purchase enough petrol to bring his “army” to the capital, suggesting that either the Vatican or Catholic Democrats had funded him in order to weaken his administration. When it was found that Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon had actually been the one to provide the gasoline he was sacked. Despite its failure Cox’s Army did result in Cox’s founding of the Jobless Party and it was still the largest demonstration ever to come to Washington.

It held that record exactly four months.

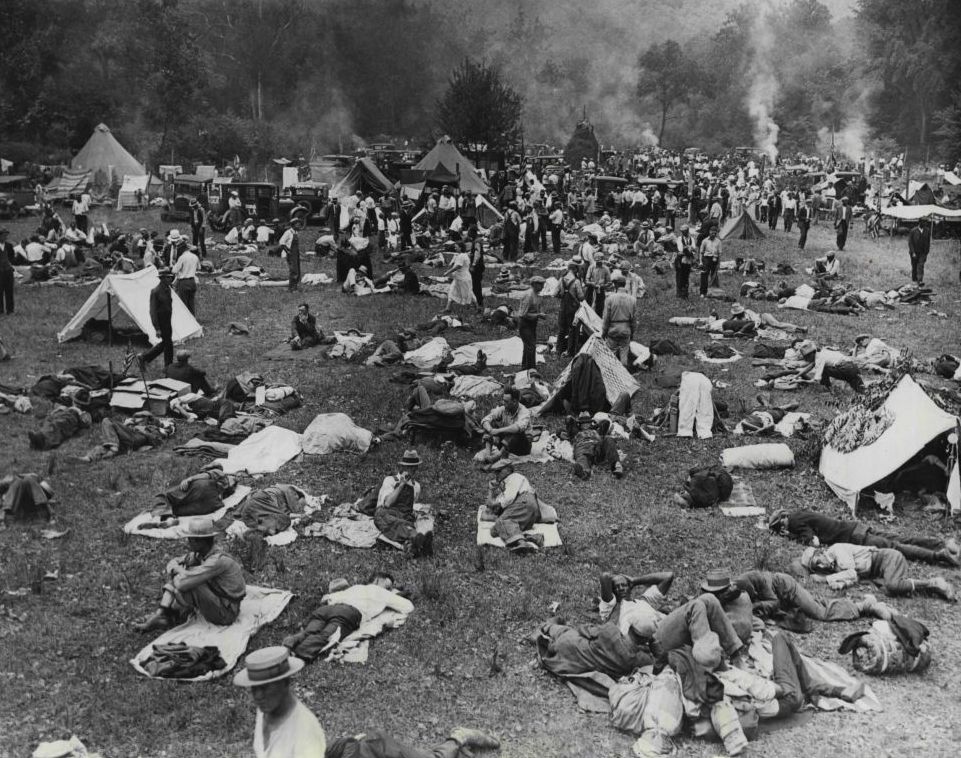

In May of that year over 26,000 penniless World War veterans descended on the capital, occupying parks, dumps, abandoned warehouses, and empty stores. The men drilled, sang marching songs, and once, led by a Medal of Honor winner and watched by a hundred thousand silent Washingtonians, they marched up Pennsylvania Avenue bearing faded American flags. They had come to ask for immediate payment of the $500 soldier’s bonuses authorized in 1924 (over President Coolidge’s veto) that were not due until 1945. Reporters named them the “Bonus Army” (later they would become known as the First Bonus Army) but they called themselves the Bonus Expeditionary Force. They appealed to President Hoover, begging him to receive a delegation of their leaders. Instead he sent word that he was too busy and proceeded to isolate himself from the rest of Washington. The White House (still standing in 1932, and still the residence of the President) was padlocked shut, policeman patrolled the grounds day and night, barricades were erected, and traffic shut down for one block on all sides of the Executive Mansion. A one-armed veteran, bent on picketing, tried to penetrate the screen of guards. He was soundly beaten and carried off to jail.

Bonus Marchers.

It was a massive overreaction. The BEF was unarmed, it had expelled radicals from its ranks, and was slowly starving to death. A reporter for the Baltimore Sundescribed them as “ragged, weary, and apathetic” with “no hope on their faces.” When Washington police tried to feed the veterans bread, coffee, and stew at six cents a day they aroused the President’s wrath who threatened to have police superintendent Pelham Glassford (who was himself a vet and a former Brigadier General) fired. But in the days before television it was possible to deny the obvious. Attorney General William D. Mitchell declared the Bonus Army “guilty of begging and other acts”. Vice President Charles Curtis called out two companies of marines to remove the marchers, at which point General Glassford noted that the Vice-President has no military authority and sent them back to their barracks. TheWashington Evening Star wondered why no District police officer had “put a healthy sock on the nose of a bonus marcher” and the New York Times reported that the marchers were veterans who were “not content with their pensions, although seven or eight times those of other countries.” (Pensions did not exist for the average veteran at this point in time) Ominously foreshadowing what was to come, Brigadier General George Mosley proposed that they arrest the bonus marchers and others “of inferior blood” and then put them in concentration camps on “one of the sparsely inhabited islands of the Hawaiian group not suited for growing sugar.” There, he suggested, “they could stew in their own filth.” He added darkly, “We would not worry about the delays in the process of law in the settlement of their individual cases.”

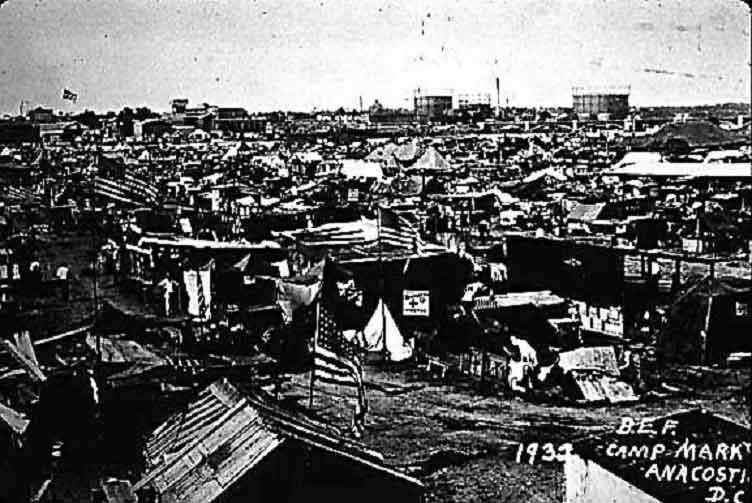

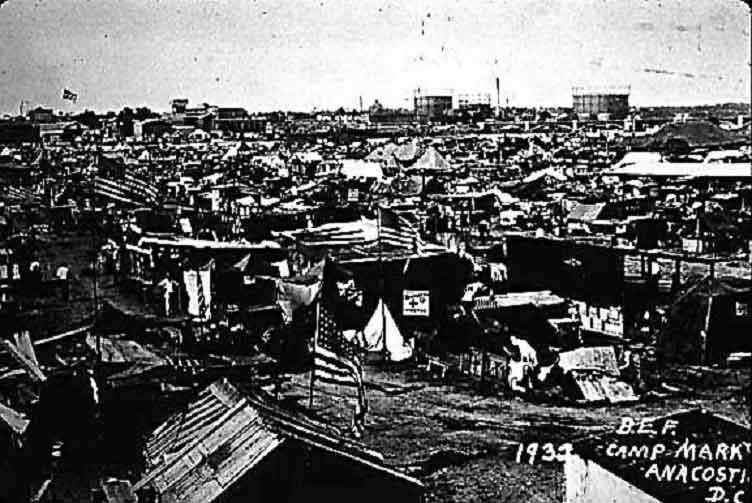

Bonus Army camp

On July 28 Glassford, who had been ordered to act by Congress, finally arrived with Washington police to begin clearing the BEF camp at Third and Pennsylvania. The clearing first went fairly peacefully, but then reinforcements arrived from the main veteran camp on Anacostia Flats who began throwing bricks. Glassford himself was struck and as he staggered backwards he watched a police officer “gone wild-eyed” shoot at a veteran. The vet- William Hruska of Chicago- fell down dead and the rest of the officers then opened fire killing another vet- Eric Carlson of Oakland. Glassford shouted “Stop the shooting!” but it was too late. Word of the incident reached the President over lunch, Hoover told Patrick Hurley (Secretary of War) to use troops, and Hurley unleashed General Douglas MacArthur.

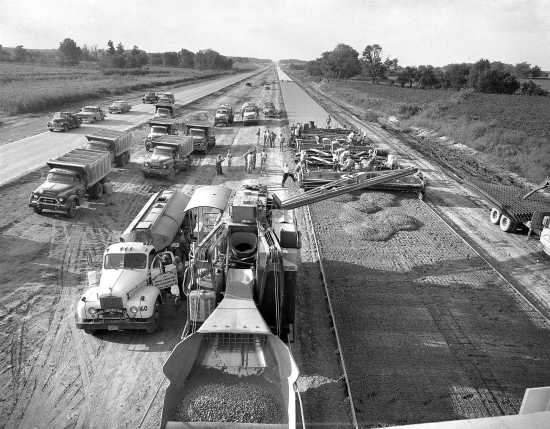

Now came a delay- the man himself wasn’t in uniform and he wanted to change. His aide, Major Dwight Eisenhower, didn’t think he should do so. “This is political, political,” Eisenhower said again and again, arguing that it was highly inappropriate for a general to become involved in a street corner brawl. The general disagreed. “MacArthur has decided to go into active command in the field,” MacArthur declared in his trademark third-person. “There is incipient revolution in the air.” An orderly was dispatched to fetch the chief’s tunic, service stripes, sharpshooter medal, and English whipcord breeches. After proceeding to Sixth and Pennsylvania another wait began, and someone asked “What’s the hold up?” “The tanks.” MacArthur replied. Meanwhile President Hoover was issuing an announcement that troops “would put an end to rioting and civil disorder” and that the men the police had clashed with “were entirely of the communist element.”

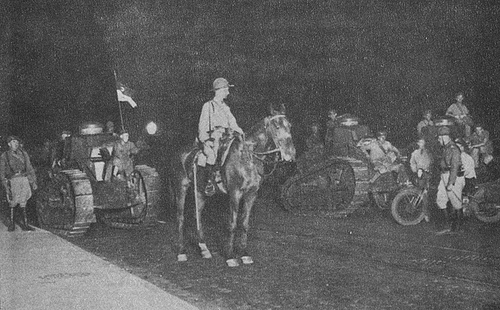

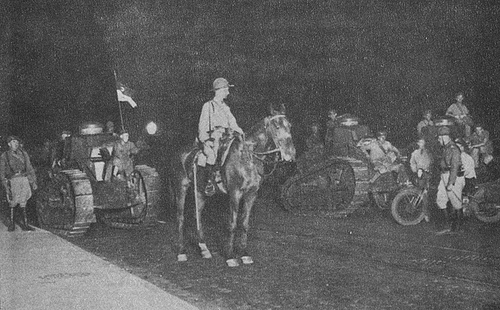

The tanks preparing to go into action.

Washingtonians watched as the 3rd Cavalry led by Major George S. Patton marched down Pennsylvania Avenue brandishing naked sabers. Behind them came a machine gun detachment, the 12th and 34th Infantry, the 13th Engineers, and six tanks, their caterpillar treads methodically destroying the soft asphalt. Abruptly Major Patton- not known for his solicitude towards civilians- charged his troops right into the growing crowd of twenty-thousand civil service workers who had just come off work. J.F.

Essary of the Baltimore Sun wrote that “thousands of unoffending people” were “ridden down indiscriminately”. Among those trampled were Senator Hiram Bingham of Connecticut. “Shame!” Shouted the spectators as they fled, at which point the cavalry finally turned on the hastily assembling veterans and charged again. The vets were stunned then furious. “Jesus!” cried one graying man- “If only we had guns!” The infantry came on the heels of the horsemen, pulling on gasmasks and throwing blue tear gas bombs. BEF women fled the camp, choking and clutching their children as they and their men retreated toward the Anacosta river. By 9 pm the refugees had withdrawn to the main Bonus Army camp and MacArthur was preparing to go in after them. General Glassford begged the general not to do it, calling a night attack the “height of stupidity. MacArthur was adamant and the police superintendent turned away.

Infantry in gas masks confronting BEF members

At this point the impossible happened- orders arrived from Hoover that “forbade any troops to cross the bridge [over the Anacostia] into the largest encampment of veterans.” The President had received reports about the debacle at Third and Pennsylvania and he was worried about the publicity in an election year. The orders were in sent in duplicate, but MacArthur merely declared to his aide that he was “too busy and did not want either himself or his staff bothered by people coming down and pretending to bring orders.” And so the attack went forward anyway- against the explicit instruction of the Commander in Chief. Again the veterans were gassed and a force of infantry advanced to attack the encampment. Vegetable gardens planted by BEF families were trampled and their makeshift homes were burned. The attack resulted in over a hundred casualties including two babies gassed to death- twelve-week old Bernard Meyers and an unnamed infant who had been born only a few hours earlier. The yachts of well-to-do Washingtonians cruised close to look at the show and watched as Major Patton led the final charge to rout the BEF. Among the men struck down by cavalry sabers was Joseph T. Angelino, who, on September 26, 1918, had won the Distinguished Service Cross in the Argonne Forest for saving the life of a young officer named George S. Patton Jr.

Eisenhower later wrote of his grave misgivings with the whole event. “The veterans, loyal Americans who had marched on Washington with perfectly legitimate grievances, were ragged, ill-fed, and felt themselves badly abused. To suddenly see the whole encampment going up in flames just added to the pity one had to feel for them. For the first time in my career I felt ashamed to be a member of the United States Army.”

The BEF camp burning

For the first time, but not the last.

Post-war borders, 1952 by Zek Sora

The Falcon Cannot Hear: The Second American Civil War 1937-1944

by Ephraim Ben Raphael

"Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand."

- The Second Coming, W.B. Yeats

Prologue - 1929

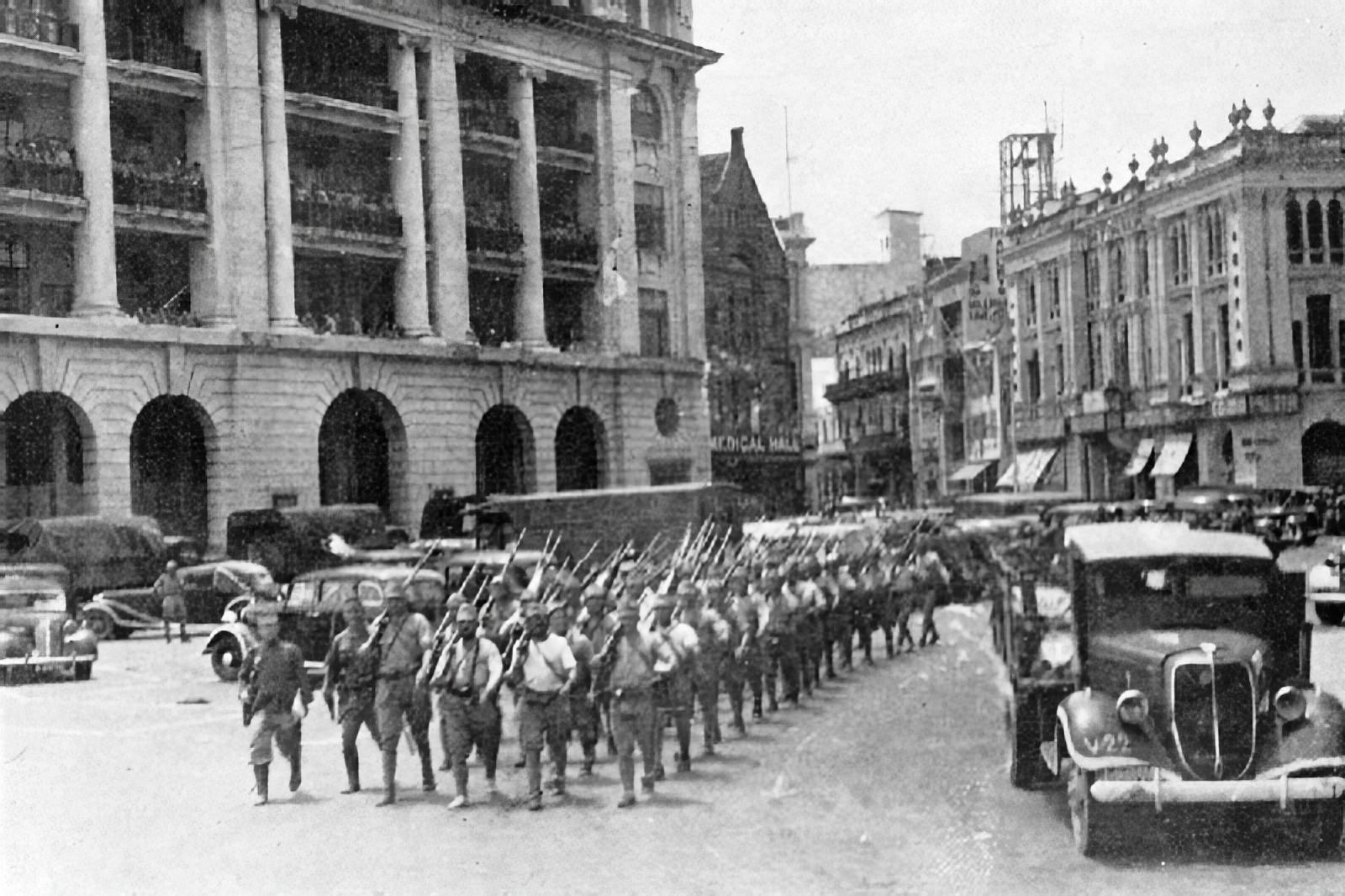

In September 1929 the United States of America was at the top its game. Europe, devastated by the First World War, was still climbing out of revolutionary turmoil of the late ‘Teens and early Twenties. National economies worldwide were wracked by uncertainty and instability, feeding simmering unrest. But in America business leaders spoke of the New Era, of the map to a New El Dorado that would allow for an ever-expanding economy, full employment, and the elimination of poverty. They scoffed at the communists in Russia with their state planned economy, America was proof that capitalism worked. The country had no enemies, Great Britain- the world’s only superpower- was a staunch ally and Lloyd’s of London offered 500-to-1 odds against any invasion of the United States. The general mood was one of optimism, complacency, and comfort. Yet within a decade America would be broken against itself, foreign troops would march down its boulevards and half-a-million Americans would die in the worst genocide to be witnessed by the New World since the annihilation of its native peoples.

A New York parts factory in 1928, at the time American industry led the world.

How could this happen? The seeds of destruction did not come from abroad, but from within the nation. As Abraham Lincoln said in 1838 “if destruction be our lot we must ourselves be its author and finisher”. It was the false underpinnings of the New Era that brought the house of cards down.

In the aftermath of the World War the techniques of mass production combined to increase the efficiency of per man-hour by over 40%. This enormous output of goods clearly required a commensurate increase in purchasing power- that is to say higher wages. But over the 1920’s income failed to keep pace with production. In the golden year of 1929 Brookings economists calculated that to supply the barest necessities a family would need an income of $2,000 a year- more than what 60% of American families were earning. The general mood of the time however, was such that overproduction was no problem, the sense was that “a good salesman can sell anything.” This meant that customers of limited means were encouraged to buy products anyhow via a massive overextension of their credit. As zealous commercial travelers sold anything and

everything to people who lacked the means to pay for it, the rich (and many who weren’t rich) speculated overwhelmingly in stocks. Arthur A. Robertson watched aghast as investors bought $500,000 of stock with only $500 down. For eight or ten dollars the smart investor could get one hundred dollars worth of stock on margin. As a consequence the slightest shake-up became a calamity as people lacked the money to cover their investments.

Then on October 29, 1929 it came time to pay the piper.

A mob outside the New York Stock Exchange on October, 29, 1929.

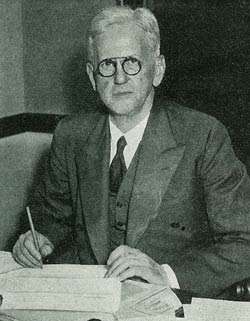

The bottom fell out of the market and stock prices plunged, going down to no more than a few percent of their former value. In one day alone the New York Stock Exchange lost between eight and nine billion dollars. That afternoon a group of New York bankers succeeded in temporarily halting the plunge, but confidence had already leaked out of the market. Five days later the panic began again and this time there was nothing anyone could do to stop it. “There has been a little distress selling on the Stock Exchange,” Thomas Lamont, Secretary of Commerce, commented in a truly remarkable display of understatement, “but conditions are still sound.” He was whistling in the dark, with few interruptions stocks would continue to fall for the next eight years.

Thomas Lamont on the cover of Time Magazine, November 1929.

Honey-combed by millions of little loans to consumers, the economy went into a downward spiral. To protect investments prices had to be maintained, as a consequence sales fell, so costs were cut by laying off employees. The unemployed could not buy the goods of other industries, therefore sales dropped further. Lower sales led to more layoffs which further shrank purchasing power, until farmers were pauperized by the poverty of industrial workers, who in turn were pauperized by the poverty of farmers. “Neither has the money to buy the product of the other,” a witness testified before congress, explaining the vicious cycle. “Hence we have overproduction and under consumption at the same time and in the same country.”

And the United States took its first hesitant steps down the road to civil war.

Things Get Bad- 1930-31

In the beginning of the year 1930 prominent persons whose word was apt to be taken seriously, declared their confidence in stocks and underlying business soundness. Even comic strip characters weighed in, “Who says business is bad?” asked Little Orphan Annie. Not Nicholas Butler, the president of Columbia University; Dr. Butler assured Columbia men that “Courage will end the slump.” Not the president of U.S. Steel; he said the “peak” of the Depression had passed. Not Owen D. Young, board chairman of General Electric; he announced that the “dead center of the Depression” had come and gone. Not a spokesman for the National Association of Manufacturers; he observed that “many of the bad effects of the so-called Depression are based on calamity howling.” Not Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon who asserted that there was “nothing in the present situation… menacing or [warranting] pessimism.” And certainly not Secretary of Commerce Thomas Lamont; he reported that “The banks of this country are in a strong position” and contented himself with listing the gains that the year 1929 had made over 1928, and predicting prosperity “in the long run.”

It was going to be a very long run.

By March of 1930 there were between 3,250,000 and 4,000,000 unemployed in the United States of America, by March 1931 those numbers had doubled to between 7,500,000 and 8,000,000. Appreciable downward changes in m manufacturing wages began in the fourth quarter of 1930, there was a general understanding among employers that high wages were necessary for recovery and so they held off on making cuts for as long as they could. This changed in August 1931 when U.S. Steel cut the salaries of its employees by 10 to 15 percent and was soon followed by the rest of the steel industry. Throughout 1931 3586 concerns cut wages for some 654,687 workers, by the end of the year hourly earnings had hit 54 cents per hour. Average weekly earnings fell even faster, in 1929 the average weekly salary of an industrial worker was above $28.50, for 1930 $25.74, and a mere $22.64 for 1931. Working hours fell from 48 per week in 1929 to 44 in 1930, to a mere 38 in the last months of 1931. Increasingly even those who were still employed watched their circumstances become more and more precarious.

And the United States took its first hesitant steps down the road to civil war.

Things Get Bad- 1930-31

In the beginning of the year 1930 prominent persons whose word was apt to be taken seriously, declared their confidence in stocks and underlying business soundness. Even comic strip characters weighed in, “Who says business is bad?” asked Little Orphan Annie. Not Nicholas Butler, the president of Columbia University; Dr. Butler assured Columbia men that “Courage will end the slump.” Not the president of U.S. Steel; he said the “peak” of the Depression had passed. Not Owen D. Young, board chairman of General Electric; he announced that the “dead center of the Depression” had come and gone. Not a spokesman for the National Association of Manufacturers; he observed that “many of the bad effects of the so-called Depression are based on calamity howling.” Not Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon who asserted that there was “nothing in the present situation… menacing or [warranting] pessimism.” And certainly not Secretary of Commerce Thomas Lamont; he reported that “The banks of this country are in a strong position” and contented himself with listing the gains that the year 1929 had made over 1928, and predicting prosperity “in the long run.”

It was going to be a very long run.

By March of 1930 there were between 3,250,000 and 4,000,000 unemployed in the United States of America, by March 1931 those numbers had doubled to between 7,500,000 and 8,000,000. Appreciable downward changes in m manufacturing wages began in the fourth quarter of 1930, there was a general understanding among employers that high wages were necessary for recovery and so they held off on making cuts for as long as they could. This changed in August 1931 when U.S. Steel cut the salaries of its employees by 10 to 15 percent and was soon followed by the rest of the steel industry. Throughout 1931 3586 concerns cut wages for some 654,687 workers, by the end of the year hourly earnings had hit 54 cents per hour. Average weekly earnings fell even faster, in 1929 the average weekly salary of an industrial worker was above $28.50, for 1930 $25.74, and a mere $22.64 for 1931. Working hours fell from 48 per week in 1929 to 44 in 1930, to a mere 38 in the last months of 1931. Increasingly even those who were still employed watched their circumstances become more and more precarious.

Unemployed workers warming themselves over trashcan fire.

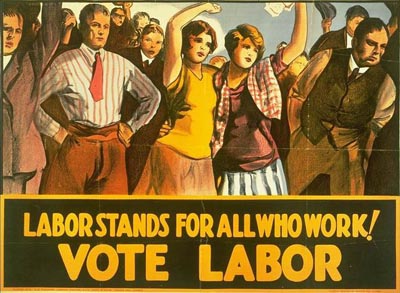

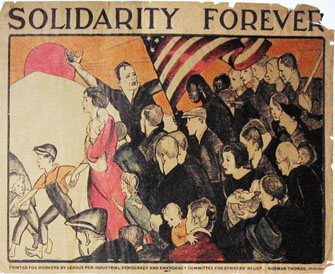

It was in the growing masses of the unemployed that the seeds of radicalism began to take hold. In 1930 the Unemployed Councils of the USA (UCU) was first organized by the American Communist Party, then a tiny organization with about 10,000 members. Similar to the soviets of unemployed workers that emerged during the 1905 Russian Revolution, the UCU was a loosely organized body based around neighborhood councils composed of alienated and disillusioned unemployed. Little co-operation existed between respective UCU councils, and in fact most of the membership had not much interest in communism. Demanding public works, relief, and state aid, the UCU was often little more than an expression of American progressive thought. However, communist organizers were very active in the movement and they were able to present their teachings for the first time to a large number of Americans- clearing ground for the expansion of the party.

A meeting of the St. Louis Unemployment Council. Note the multiracial nature of the membership.

On March 6, 1930 the “International Struggle against Worldwide Unemployment” was called by the Communist International. Across the United States some 100,000- 200,000 members of the UCU turned out to protest calling for “Work or Wages” and demanding that President Hoover do something to address the issue of unemployment. Law enforcement cracked down on the organization, arresting many of its leaders including William Z. Foster, but the diffuse nature of the UCU’s structure meant that the government response helped the councils more than it hurt them. The free publicity caused Unemployment Councils to swell, and although the Communist Party would attempt to establish a more rigid hierarchy for the councils later that year they were never truly able to control their creation.

From left to right; William Z. Foster, Robert Minor, and Israel Amter. The three communists and leaders of the UCU being arrested on March 6, 1930 for connection to the Unemployment Day Protests.

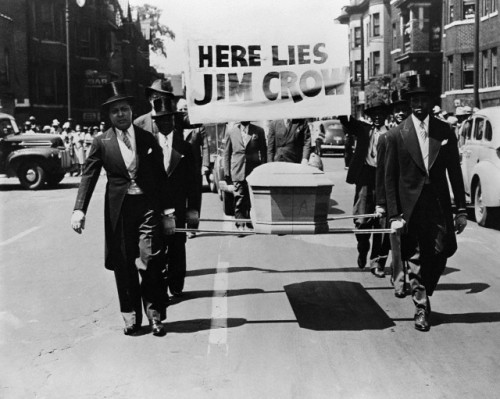

On October 16, 1930 as unemployed and police skirmished in the streets of New York, Sam Nessin, one of the leaders of the New York Unemployed Councils addressed the city council calling for relief. Mayor Jimmy Walker condemned Nessin calling him a “dirty Red” at which point police beat the activist and four of his companions with nightsticks and removed them from the hall. Nessin was later charged with “inciting riot”. Meanwhile Unemployed Councils stormed supermarkets and organized protests nationally, recruiting from amongst the disenfranchised and the desperate. Their willingness to recruit both black and white citizens both hurt and helped the UCU’s appeal in the south, in the north they frequently made inroads into immigrant communities.

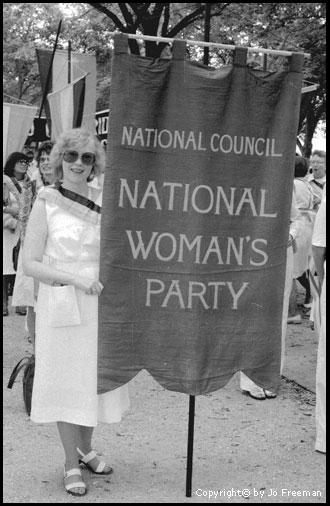

Largely thanks to their involvement in the Unemployed Councils, the Communist Party swelled massively- by the end of 1931 they had increased ten-fold with some 100,000 members. Still neither they, nor the Socialists were able to make much headway in the 1930 elections which saw the Democrats take control of both houses. For the time being Congress remained the province of the Democrats and Republicans (excepting a single representative and a single senator both belonging to the Farmer-Labor Party). The political fragmentation that would emerge later in the thirties was yet to come.

President Hoover- 1929-1932

Unfortunately for the country the man in the White House was Herbert Clark Hoover, elected in 1928 in a landslide. A man who “couldn’t bear to watch suffering” he never visited a breadline or a relief station, despite the pleas of William Allen White. Since taking the oath of office on March 4, 1929 Hoover had not once left the capital to see the states that he had toured during his campaign. He did not turn his head when his limousine swept past apple salesmen on street corners. The President did briefly consider economy for the White House kitchen, but he decided that would be “bad for national morale.” Each evening he entered the dining room wearing black tie and sat down to seven full courses while men starved in streets and alleyways. Usually some of the courses were out of season, as were the cut flowers for the table. A custom-built humidor held long thick cigars handmade in Havana to the President’s specifications; he smoked twenty a day. As Mr. and Mrs. Hoover sat down to eat they were always attended by a butler and several footmen- all had to be the same height- who stood at stiff attention, absolutely silent, forbidden to move unbidden. In the doorways were duty officers from the company of marines who stood by wearing dress blues, to provide ceremonial trappings, and there were buglers in Ruritanian uniforms whose glittering trumpets announced the President’s arrival and departure from the nightly feast.

Largely thanks to their involvement in the Unemployed Councils, the Communist Party swelled massively- by the end of 1931 they had increased ten-fold with some 100,000 members. Still neither they, nor the Socialists were able to make much headway in the 1930 elections which saw the Democrats take control of both houses. For the time being Congress remained the province of the Democrats and Republicans (excepting a single representative and a single senator both belonging to the Farmer-Labor Party). The political fragmentation that would emerge later in the thirties was yet to come.

President Hoover- 1929-1932

Unfortunately for the country the man in the White House was Herbert Clark Hoover, elected in 1928 in a landslide. A man who “couldn’t bear to watch suffering” he never visited a breadline or a relief station, despite the pleas of William Allen White. Since taking the oath of office on March 4, 1929 Hoover had not once left the capital to see the states that he had toured during his campaign. He did not turn his head when his limousine swept past apple salesmen on street corners. The President did briefly consider economy for the White House kitchen, but he decided that would be “bad for national morale.” Each evening he entered the dining room wearing black tie and sat down to seven full courses while men starved in streets and alleyways. Usually some of the courses were out of season, as were the cut flowers for the table. A custom-built humidor held long thick cigars handmade in Havana to the President’s specifications; he smoked twenty a day. As Mr. and Mrs. Hoover sat down to eat they were always attended by a butler and several footmen- all had to be the same height- who stood at stiff attention, absolutely silent, forbidden to move unbidden. In the doorways were duty officers from the company of marines who stood by wearing dress blues, to provide ceremonial trappings, and there were buglers in Ruritanian uniforms whose glittering trumpets announced the President’s arrival and departure from the nightly feast.

President Hoover making a radio address.

His election slogan in 1928 had been “A chicken in every pot and two cars in every garage”.

The American people meanwhile were not unaware of their commander-in-chief’s apathy, and they castigate him for it. The junkyard shanty towns that sprang up across the country were called “Hoovervilles”, the unemployed carried sacks of frayed belongings known as “Hoover bags”. The rural poor sawed off the fronts of broken-down flivvers, attached scrawny mules, and called the result “Hooverchariots”. The President tried to have the name changed to “Depression chariots” but no one bought it. “Hoover blankets” were old newspapers the homeless wrapped around themselves for warmth. “Hoover flags” were pockets turned inside out. “Hoover hogs” the jackrabbits hungry farmers caught for food. One popular joke of the time was to claim that Hoover asked Secretary Mellon for a nickel to telephone a friend and was told “Here’s a dime, phone both of them.”

The President explained his belief that the function of government was to “bring about a condition of affairs to the beneficial development of private enterprise”, adding that the only “moral” way out of the Depression was self-help; the people should find inspiration in the devotion of “great manufacturers, our railways, utilities, business houses, and public officials.” Since by this point the greater part of the people believed that the great manufacturers were a bunch of crooks this went over like a lead balloon. Hoover was a great advocate of conventional wisdom, he held the gold standard to be sacred even though eighteen nations lead by Great Britain had already abandoned it. He was convinced that a balanced budget was “the most essential factor to economic recovery”- despite the fact that by 1932 he had run the budget 4 billion dollars into the red. When he was at last convinced to do something about the Depression (whose name he himself had coined, it sounded less severe than “Panic”) he created the Reconstruction Finance Corporation to prop up sagging banks, and agreed to spend twenty-five million dollars on feed for farm animals on the condition that a bill authorizing one hundred and twenty thousand dollars for hungry people be tabled. The RFC promptly loaned 90 million dollars to the Central Republic Bank and Trust Company of Chicago of which the RFC chairman, Charles G. Dawes (former vice-president of the United States), was an officer, and a mere 30 million to state governments for unemployment relief. People called it “a breadline for big business”, which in a sense it was.

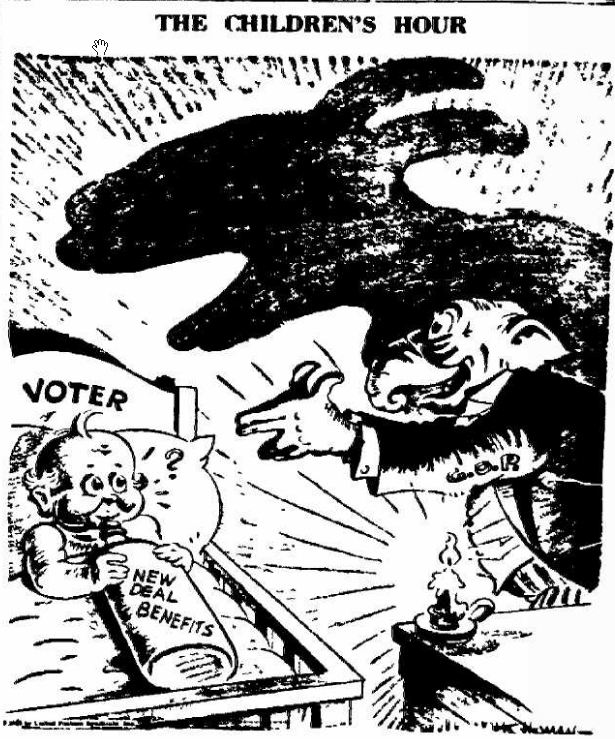

The National Association of Manufacturers put up murals like these in major American cities as part of their campaign to support the President and discourage liberal opposition.

Still Hoover persisted in his views, unwilling to acknowledge that the country was truly in trouble. In December 1929 he declared that “conditions are fundamentally sound”. Three months later he said that the worst would be over in sixty days; at the end of May he predicted the economy would be back to normal by autumn; in June the market broke sharply, yet he told a delegation which came to plead for a public works project, “Gentlemen, you have come sixty days too late. The Depression is over.” On December 2, 1930 the President informed the lame-duck Republican congress that “the fundamental strength of the economy is unimpaired.” About the same time the International Apple Shipper Association decided to unload its surplus of apples by selling them on credit to jobless men for resale at a nickel each. Overnight the street corners became crowded with shivering apple salesmen. When asked about them, Hoover replied, “Many people have left their jobs for the more profitable one of selling apples.” When reporters’ questions turned to hunger he dismissed the problem, saying that “Nobody is actually starving. The hoboes for example, are better fed than they ever have been. One hobo in New York got ten meals in one day.” This when the New York City Welfare Council was reporting 110 (mostly children) dead of malnutrition.

A Washington, D.C. Apple Salesman.

On the streets of New York children sang;

Mellon pulled the whistle

Hoover rang the bell

Wall Street gave the signal

And the country went to hell.

Going into the year 1932 and the coming election Hoover was the subject of biting criticism and ridicule, nevertheless he hung on tightly to his optimism. Surely the hardworking American people would prefer a President who believed in the value of self-reliance? The economy had been bad for more than two years by that point and he was confident that it had to turn around sooner or later- why not in an election year? Meanwhile in the streets and crowded Hoovervilles the situation just kept on getting worse and worse.

Washington Under Siege- 1932

In January of 1932 a former army chaplain named James Renshaw Cox led a march of 25,000 unemployed Pennsylvanians to Washington, D.C. Supported by numerous notables including Pennsylvania governor Gifford Pinchot (a Republican), “Cox’s Army” was quickly broken up and dispersed. An embarrassed Hoover ordered a criminal investigation into how Cox was able to purchase enough petrol to bring his “army” to the capital, suggesting that either the Vatican or Catholic Democrats had funded him in order to weaken his administration. When it was found that Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon had actually been the one to provide the gasoline he was sacked. Despite its failure Cox’s Army did result in Cox’s founding of the Jobless Party and it was still the largest demonstration ever to come to Washington.

It held that record exactly four months.

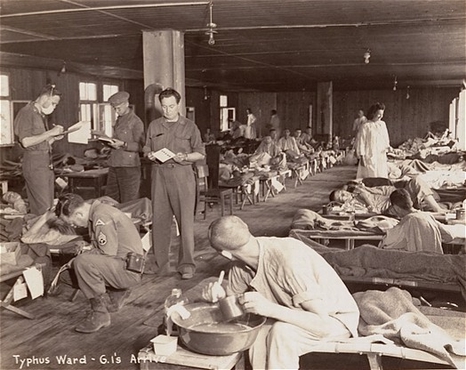

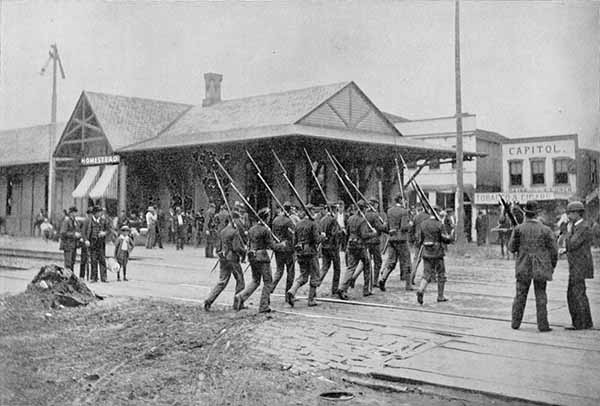

In May of that year over 26,000 penniless World War veterans descended on the capital, occupying parks, dumps, abandoned warehouses, and empty stores. The men drilled, sang marching songs, and once, led by a Medal of Honor winner and watched by a hundred thousand silent Washingtonians, they marched up Pennsylvania Avenue bearing faded American flags. They had come to ask for immediate payment of the $500 soldier’s bonuses authorized in 1924 (over President Coolidge’s veto) that were not due until 1945. Reporters named them the “Bonus Army” (later they would become known as the First Bonus Army) but they called themselves the Bonus Expeditionary Force. They appealed to President Hoover, begging him to receive a delegation of their leaders. Instead he sent word that he was too busy and proceeded to isolate himself from the rest of Washington. The White House (still standing in 1932, and still the residence of the President) was padlocked shut, policeman patrolled the grounds day and night, barricades were erected, and traffic shut down for one block on all sides of the Executive Mansion. A one-armed veteran, bent on picketing, tried to penetrate the screen of guards. He was soundly beaten and carried off to jail.

Bonus Marchers.

It was a massive overreaction. The BEF was unarmed, it had expelled radicals from its ranks, and was slowly starving to death. A reporter for the Baltimore Sundescribed them as “ragged, weary, and apathetic” with “no hope on their faces.” When Washington police tried to feed the veterans bread, coffee, and stew at six cents a day they aroused the President’s wrath who threatened to have police superintendent Pelham Glassford (who was himself a vet and a former Brigadier General) fired. But in the days before television it was possible to deny the obvious. Attorney General William D. Mitchell declared the Bonus Army “guilty of begging and other acts”. Vice President Charles Curtis called out two companies of marines to remove the marchers, at which point General Glassford noted that the Vice-President has no military authority and sent them back to their barracks. TheWashington Evening Star wondered why no District police officer had “put a healthy sock on the nose of a bonus marcher” and the New York Times reported that the marchers were veterans who were “not content with their pensions, although seven or eight times those of other countries.” (Pensions did not exist for the average veteran at this point in time) Ominously foreshadowing what was to come, Brigadier General George Mosley proposed that they arrest the bonus marchers and others “of inferior blood” and then put them in concentration camps on “one of the sparsely inhabited islands of the Hawaiian group not suited for growing sugar.” There, he suggested, “they could stew in their own filth.” He added darkly, “We would not worry about the delays in the process of law in the settlement of their individual cases.”

Bonus Army camp

On July 28 Glassford, who had been ordered to act by Congress, finally arrived with Washington police to begin clearing the BEF camp at Third and Pennsylvania. The clearing first went fairly peacefully, but then reinforcements arrived from the main veteran camp on Anacostia Flats who began throwing bricks. Glassford himself was struck and as he staggered backwards he watched a police officer “gone wild-eyed” shoot at a veteran. The vet- William Hruska of Chicago- fell down dead and the rest of the officers then opened fire killing another vet- Eric Carlson of Oakland. Glassford shouted “Stop the shooting!” but it was too late. Word of the incident reached the President over lunch, Hoover told Patrick Hurley (Secretary of War) to use troops, and Hurley unleashed General Douglas MacArthur.

Now came a delay- the man himself wasn’t in uniform and he wanted to change. His aide, Major Dwight Eisenhower, didn’t think he should do so. “This is political, political,” Eisenhower said again and again, arguing that it was highly inappropriate for a general to become involved in a street corner brawl. The general disagreed. “MacArthur has decided to go into active command in the field,” MacArthur declared in his trademark third-person. “There is incipient revolution in the air.” An orderly was dispatched to fetch the chief’s tunic, service stripes, sharpshooter medal, and English whipcord breeches. After proceeding to Sixth and Pennsylvania another wait began, and someone asked “What’s the hold up?” “The tanks.” MacArthur replied. Meanwhile President Hoover was issuing an announcement that troops “would put an end to rioting and civil disorder” and that the men the police had clashed with “were entirely of the communist element.”

The tanks preparing to go into action.

Washingtonians watched as the 3rd Cavalry led by Major George S. Patton marched down Pennsylvania Avenue brandishing naked sabers. Behind them came a machine gun detachment, the 12th and 34th Infantry, the 13th Engineers, and six tanks, their caterpillar treads methodically destroying the soft asphalt. Abruptly Major Patton- not known for his solicitude towards civilians- charged his troops right into the growing crowd of twenty-thousand civil service workers who had just come off work. J.F.

Essary of the Baltimore Sun wrote that “thousands of unoffending people” were “ridden down indiscriminately”. Among those trampled were Senator Hiram Bingham of Connecticut. “Shame!” Shouted the spectators as they fled, at which point the cavalry finally turned on the hastily assembling veterans and charged again. The vets were stunned then furious. “Jesus!” cried one graying man- “If only we had guns!” The infantry came on the heels of the horsemen, pulling on gasmasks and throwing blue tear gas bombs. BEF women fled the camp, choking and clutching their children as they and their men retreated toward the Anacosta river. By 9 pm the refugees had withdrawn to the main Bonus Army camp and MacArthur was preparing to go in after them. General Glassford begged the general not to do it, calling a night attack the “height of stupidity. MacArthur was adamant and the police superintendent turned away.

Infantry in gas masks confronting BEF members

At this point the impossible happened- orders arrived from Hoover that “forbade any troops to cross the bridge [over the Anacostia] into the largest encampment of veterans.” The President had received reports about the debacle at Third and Pennsylvania and he was worried about the publicity in an election year. The orders were in sent in duplicate, but MacArthur merely declared to his aide that he was “too busy and did not want either himself or his staff bothered by people coming down and pretending to bring orders.” And so the attack went forward anyway- against the explicit instruction of the Commander in Chief. Again the veterans were gassed and a force of infantry advanced to attack the encampment. Vegetable gardens planted by BEF families were trampled and their makeshift homes were burned. The attack resulted in over a hundred casualties including two babies gassed to death- twelve-week old Bernard Meyers and an unnamed infant who had been born only a few hours earlier. The yachts of well-to-do Washingtonians cruised close to look at the show and watched as Major Patton led the final charge to rout the BEF. Among the men struck down by cavalry sabers was Joseph T. Angelino, who, on September 26, 1918, had won the Distinguished Service Cross in the Argonne Forest for saving the life of a young officer named George S. Patton Jr.

Eisenhower later wrote of his grave misgivings with the whole event. “The veterans, loyal Americans who had marched on Washington with perfectly legitimate grievances, were ragged, ill-fed, and felt themselves badly abused. To suddenly see the whole encampment going up in flames just added to the pity one had to feel for them. For the first time in my career I felt ashamed to be a member of the United States Army.”

The BEF camp burning

For the first time, but not the last.

Last edited:

![Mar07LN-blog480[1].jpg](/forum/proxy.php?image=http%3A%2F%2Frhymeswithright.mu.nu%2Farchives%2Fimages%2FMar07LN-blog480%5B1%5D.jpg&hash=aa9c8caabd0698a9ef8731cb4f70c47f)