You know, we've been focused on the downsides for England; but a Puritan Connecticut and Rhode Island won't be the free thinking places of OTL, either. gah.

Very true. While Cromwell’s religious convictions are the same as OTL and he’s quite willing to let practical considerations take priority if necessary, the Saybrook proprietors have a very clear idea of the sort of colony they want to emigrate to, and it doesn’t involve much in the way of religious toleration. An *Anne Hutchinson affair would probably be smoothed over under Cromwell's watch if he were left to his own devices, but not if Lord Saye and Sele and Lord Brooke have anything to do with it.

Saybrook is still going to be a little more liberal than the Massachusetts Bay but not as much as Connecticut was IOTL; and for all that Cromwell is reasonably tolerant of doctrinal dissent, he has his limits. Roger Williams has just found himself a very powerful new enemy to add to all the others, and this probably doesn’t bode particularly well for the long-term success of the Providence Plantations.

Any chance Cromwell could build on the relationship with the (Irish) Plantations?

If political turmoil and military conflict can't be used to prompt a few thousands to head West, then Oliver isn't half as canny as I would have thought him.

Which could make all the difference along the road.

Excellent point. As it happens there was a surprising amount of interest in the Saybrook venture from Ulster in particular, which never really went anywhere after the colony folded. Even before 1641 there’s a better chance of attracting colonists who are getting increasingly wary of the situation in Ireland; after the rebellion starts, there’s a potentially impressive harvest to be reaped there, I agree.

Two questions: First, is the use of the term Revolution significant or is that an interchangeable term with Civil War in real life as well?

Some people refer to the Civil War as the “English Revolution” IOTL, and with good cause; as for whether there is more reason for historians of the future ABM-verse to use the phrase, you’ll have to wait and see…

And second, IOTL New York would, once coming under English control, claim the Connecticut River as its eastern boundary for a few decades, while Connecticut would claim out to the Hudson and even beyond,

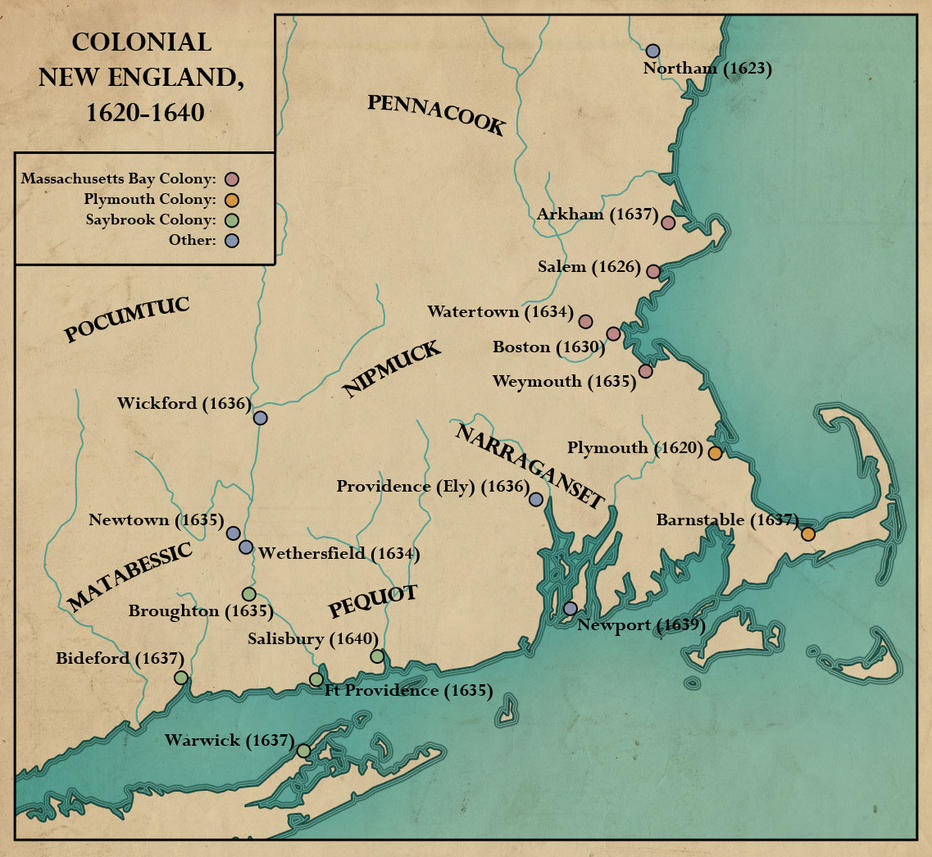

like so (best map I could find for this). Would we still see such disputes with a more firmly established Connecticut* (in the form of Saybrook)?

Oh, definitely. Even laying aside what happens to the New Netherlands, the region’s a mass of conflicting claims, some of which more enforceable than others. The Warwick Patent, which established the legality of the colony, is rather vague on boundaries and in any case was potentially superseded by another grant made two years later, which is where the New York claim to the Connecticut River comes from.

As far as Cromwell is concerned, the most important consideration is the northern border of the Saybrook Colony- what is it? Cromwell would doubtless claim that he was appointed Governor of “The Connecticut River and all places and harbours adjoining”, which effectively takes in everything up to OTL’s Canadian-New Hampshire border; the inhabitants of Windsor and Wickford (OTL Springfield, Mass) would argue otherwise, however, as would many in Boston.

Sorting out this sort of thing is going to be a major pre-occupation of Cromwell’s time as Governor. Luckily, he’s a persistent and ruthless sort, who is probably more inclined to take precipitate action to assert his claims than his rivals would imagine.

Arkham, Mass.? Nice.

Miskatonic University is a nice touch too.

Yep. Named after the Reverend Thomas Arkasden, formerly of Emanuel College, Cambridge, and Ampthill, Bedfordshire; he was inspired by a lecture Cromwell gave at his old alma mater in 1636 and brings his congregation over to New England along with him, along with a suspiciously extensive collection of esoteric books that will later form the core of the town’s university library…

I'm loving this, EdT - especially after seeing your second map on Deviantart

... can't wait to see where you go with it, this should be an exciting ride! Glad I can finally get in on the ground floor, as it were, of one of your timelines!

Well, remember that the maps aren’t necessarily canon- they represent my best guess at the time I made them but I generally retcon them as I go on. But yes, North America is going to look quite different quite quickly with Cromwell added to the equation.

Is "social gospel" anachronistic? It sounds anachronistic to me, but I am willing to bear correction.

Certainly the capitalised, progressive “Social Gospel” is anachronistic, but the un-capitalised phrase seems to be used a fair bit in modern discussion of the period, which is where I’ve got it from. It’s meant in the context of Puritans seeking to reform the world in the image of God’s Holy Kingdom; John Winthrop’s “Christian Charity” sermon is the sort of thing which I’m trying to get at.

I’m no theologian though, so it may well be that another phrase is more suitable. Open to suggestions if so!