Chapter 40

The Land of God and War

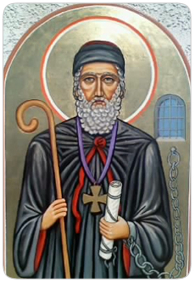

Iconic depiction of Mar Abba the Great of the Church of the East.

“O! Lord of desert sands

Lord of hot, dry winds

Whose noble warrior bands

Fight to extinguish their sins

While men of many faiths do hear

Your single voice and fear.”

- Liam McGowan, Yearningist Poet [FN1]

Of Fire and Might: A History of Politics and Religion in Sassanid Persia

By: Coahm O’Seachnall

[Royal University Press: Carrickfergus, Kingdom of Gaelia, 1992]

…

The death of Kuwas and the succession of his son Khavahd II was a peaceful occurance. Despite the upheaval of Kuwas’ early reign, his victories over the Rhomans and the Arabic states had gained legitimacy for his many reforms. Although raising the Mazdakian sect over the traditional Orthodox Zorastrian priests caused turmoil, this subsided in later years; partially because a number of his most prominent Magi opponents died during the Plague of Belisarius, but also because a new generation of nobility were coming to power to whom Mazdakianism had been the norm throughout their lives.

However, the old tensions did not abate fully. Whereas Mazdakianism drew its support from Persia’s eastern lands, Orthodox Zoroastrianism remained powerful in the western provinces from which is had first sprang centuries before. These lands were essential to the Sasanian state as they were where the dynasty had first rose to prominence and from where it drew much of its manpower. Ever since the rise of the Sasanian dynasty in the 3rd century AD, the royal family had derived its legitimacy by being patrons and supports of the Zoroastrian faith. The reforms of Kuwas and the adoption of Mazdakianism reversed this traditional policy. Kuwas attempted to compensate by drawing support from the Empire’s peasantry, who were strong support of, and benefited from, Mazdakianism. Iconographic evidence hints that Khavahd II felt the need to reassert the dynasty’s traditional legitimacy by associating with Zoroastrianism. Coins and inscriptions created during his reign present traditional Zoroastrian symbols next to those associated with the newer sect. It seems logical to assume that that Khavahd II sought to present Mazdakianism as a reformation of Zoroastrianism, and a return to the purity of the older faith. [FN1]

If this is correct, the attempts failed. Although Mazdakianism remained popular amongst the peasantry during Khavahd II’s reign, it made only small gains throughout the traditional nobility. Most nobles remained adherents to the Orthodox sect, having no need for the communalism that Mazdakianism promoted and which threatened to further erode their own personal power. Their loyalty to Khavahd, like that to his father, stemmed from the Shah’s abilities in battle, as well as his personal charisma. Khavahd was reputed to be a highly gracious and popular man who built strong personal connections to those thought fought with him and served him.

Those nobles who drifted away from Orthodoxy had a greater tendency of accepting the growing Christian movement of the Church of the East. Although previous rulers had persecuted the Church, Kuwas and his son both rescinded the persecution, believing that the Christians would be useful allies against the Orthodox Magi. Christianity appealed to many members of the nobility for it preached many of the same ideals as Mazdakianism without promising to undermine their personal power and came with an established hierarchy and governmental structure. Mar Ezekiel I, leader of the Eastern Church, exploited the end of the persecution and built upon the work of his predecessor Aba to reach out to as many Persians as possible. Like Aba, Ezekiel was a former Zoroastrian who converted to Christianity as a young man. He had been a Mazdakian who came to regret what he saw as the excesses of the movement and the anarchy they threatened to unleash upon Persia. Due to his background he understood the Persian peoples and the Zoroastrian faith and released several writings during his life which have gone down as classic defenses of Eastern Christianity, logically arguing for the correctness of the Nestorian position, while also stressing the need to remain loyal to the Persian state. [FN1]

…

Although Khavahd II’s early reign was marked by a string of victories against the Arabic states in the eastern peninsula – victories that would increase tension with Himyar as it sought hegemony over the entirety of the Arabian peninsula – growing unrest forced him to turn his eyes back to the East. From 573 through 585 a number of Orthodox revolts burned through the Sassanian state, led by the Magi and rebellious eastern nobles. The most major of these revolts was a war that lasted between 776 through 780 and came close to toppling Khavadh in favor of his cousin Hormizd. The rebels were pushed back and defeated, and the Shah was forced to spend the next five years pacifying eastern Persia. His response to the final end of the revolt was uncharacteristically harsh, for a man who was prided on his amiable relations. Mazdakianism had long fought for the extinguishing of all sacred fires except for the three most prominent. Khavadh bowed to the wishes of the Mazdakian priests and had the other flames forcibly extinguished, sending his soldiers to destroy all other temples. He also confiscated the lands of the rebellious nobles and gave them to the peasants, allowing them to choose their own leaders to rule over them. [FN3]

The Desert Wheel: The Rise of Manichaenism in Arabia [vol. VI of “The Cross, the Star, the Flame and the Wheel: Studies in the Faiths of the Middle East”]

By: Dariush Esfahani

[Mar Simon University Press, Ctesiphon, 2009]

…

Although Manichaeism had been present in Arabia for over two centuries, it was but one of many faiths that co-mingled in that desert peninsula, competing for converts with Christians, Jews, Zoroastrians and the traditional pagan traditions of that land. It was not until the time of the Prophet Abdul-Bari that it began to experience the dramatic gains that would eventually lead it to become the dominant force in, not only Arabia, much much of Africa and the Indian Ocean.

Not much can be said for sure about Abdul-Bari. Held in reverence as the most holy figure of the Arabian Manichaeist sect, much was written about him in the early years of the faith. However, most of these works are hagiography at heart and less concerned with giving an accurate appraisal of Abdul-Bari’s life and more concerned with teaching important moral lessons to those that came later. This is very similar to the problems faced with scholars attempting to trace the historical roots of Jesus Christ, Agmundr Thorson, or the Buddha, or a multitude of other holy figures.

A general historical consensus has arisen over the years, which I will explain here. For those willing to dig deeper into this fascinating subject, I would happily suggest that they seek out the work of Petros Galanos and his wonderful work

The Search for the Historical Abdul-Bari. I am greatly indebted to his work and much of the following summary derives from his scholarship.

…

Abdul-Bari was a Bedouin trader that grew up within the community of Yanbo. At an early age, his father was killed in a raid upon his caravan, and his mother died; possibly during the Plague of Belisarius, which we know struck the region with a particular vengeance. Orphaned at a young age, he apparently ran the streets for a number of years. All biographies of Abdul-Bari stress his years on the street as a formative experience in the Prophet’s early life and use them to explain his particular devotion to the poor and orphans in later life. Eventually, he was taken in by a rich merchant named Ibrahim Maloof, a member of the local Arabic Jewish community and a leader in the city. Under Maloof’s guidance, Abdul-Bari was taught the in and outs of the merchant trade and even became a member of the family by marrying Maloof’s daughter, Ayisha. [FN4]

…

With the support of Maloof, Abdul-Bari became a prominent merchant in his own right and was soon being viewed as one of the most prominent members of Yanbo. However, he was deeply unhappy. Although he never appears to have adopted the Judaism of his patron, Abdul-Bari began a search for spiritual enlightenment that would come to set the course for the rest of his life. We are told, and have no reason to doubt, that he jumped from one faith to another, becoming the follower of Monophysite Christianity, Judaism, and Zoroastrianism in turn. Finally, he fell into the circle of a charismatic preacher Faquad, a Manichaen. He quickly became recognized as one of Faquad’s most promising disciples. After his teacher’s death – we aren’t sure the exact date, but it was likely in the 570s – he became the new leader of the community.

Abdul-Bari became a noted preacher in his own right, using his merchant connections and prominence to draw many new converted into the fold. This was during the era in which Himyar was spreading its dominance throughout the entire Hejaz region. Although Ibrahim the Magnificent proved tolerant of religious differences within his realm, there was no question that he favored Jews in his administration. As many prominent members of Judaism were promoted to top positions within Ibrahim’s government in Yanbo, a natural backlash occurred. On the frontier, and far from the seat of power Yanbo proved difficult to administer. The traditional pagan families appear to have returned to power and done so with a vengeance. This pattern would be repeated throughout the Hejaz as Himyar rule began to unravel during the end of the 6th century and early 7th century.

In Yanbo, the newly reestablished Pagan rulers chose to persecute many of the city’s religious minorities. The city’s Jewish residents bore the greatest brunt of these attacks, but Abdul-Bari’s Manichaenism also faced their fair share of persecution. Eventually it was decided by the group to flee the city and head out into the desert for their own safety. They would wander from community to community for the next two decades, surviving as traders, and growing in numbers as they passed through city after city. One of the greatest converts was a caravan-man by the name of Abbas who would become one of the greatest figures in Arabian history following Abdul-Bari himself. Athough the Prophet himself remained illiterate, others in his circle took down his words and passed them around; these forming the basis of the

Book of the Prophet which would become the most holy book in the faith, even eclipsing those of Mani himself.

…

One of the most striking features of the Manichaeism that developed in Arabia is that it diverged from the, for lack of a better term, orthodox faith in a number of important ways. We have no evidence that Abdul-Bari preached that he was the reincarnation of the prophet Mani, but in the decades following his death, this became the common view. Abdul-Bari also introduced a number of important reforms which helped the faith spread amongst the Arabian people. In traditional Manichaeism, and in the non-Arabian sects that still exist in Central Asia and China to this very day, the Church had a strong hierarchy in which the Elect were the leaders and open to salvation and the congregation were merely ‘Hearers.’ In Arabia the Elect and Hearers maintained their distinction, but with several notable differences. Abdul-Bari preached that Hearers were entitled to the same salvation as the election. Furthermore, although the Arabian sect maintained the traditional view that Satan had helped create the world, it made two important innovations. First, it stressed that God was still greater than that the victory of good over evil was assured. Secondly, it said that the good had a duty to spread the faith in order to redeem creation. As a result, Arabian Manichaeism developed the belief that evil could be conquered and that it was the duty of all followers to help turn the world into a paradise. Finally, traditional Manichaeism was famous for its attempts to adopt figures from other religions. Abdul-Bari took this a step further and openly preached that other major faiths, such as Christianity, Judiasm or Zoroastrianism were corrupted versions of the true faith. The followers of these religions still worshipped the One True God and were opposed to Satan, even if their understandings were corrupted by the Devil. Because of this, followers of other faiths were to be protected at all costs, so that they might be brought into the fold of the true church. Perhaps based on his own life experiences, Abdul-Bari strictly forbid any efforts to persecute other Dualistic of Monotheistic faiths, claiming that all who did so did the work of Satan. Although this traditional protection did not spread to Pagan faiths (indeed the Arabian Manichaeists found themselves strongly opposed to Pagans in their early history), and religious violence would occur, it is notable that throughout the history of the faith, a great deal of toleration continued to be extended towards believers of all religions and the Manichaens would often attempt to absorb pagan figures in their efforts to spread their faith.

…

As a result of these reforms, Arabian Manichaenism became much less heriarchial than the more traditional forms of the faith. The Elect continued to exist, and they were seen as a spiritual peak which was to be strived for, but the Hearers were seen as just as worthy of salvation. Despite accepting that the world was created by Satan, the Arabian Manichaenism believed that it was still redeemable and, as a result, were deeply involved in the world. Because of this, many Manichaens gave freely to charaties and this, in turn, inspired further converts.

…

By the time of the Holy War in the 620s, the Manichaens were a vibrant religious minority within Arabia. Although persecuted in many cities, and hated by the Pagans, they were loved by many residents for their charity and pious ways. A self sufficient community, they were well placed to take advantage of the chaos caused by the fall of Himyar in that decade. In doing so, they went from a small desert sect to one of the major forces in the world, in just a few short decades. [FN5]

[FN1] Mazdakianism can best be seen as an attempt to reform the Zoroastrian faith and ‘get back to the basics.’ In many ways it resembles some of the more radical beliefs that arose in Christianity during the Reformation era. Since getting coopted by the Shah, Mazdakianism has been forced to moderate somewhat. The Shahs see it as a potent weapon to undermine the traditional priesthood and nobility, but have no desire to follow through on all Mazdakian designs. Despite this, it had introduced a limited amount of communalism throughout Persia and, as such, remains very popular amongst the peasantry.

[FN2] Mar Ezekiel shares a name with a historical figure from this same time, but not the personality. This Mar Ezekial is a dynamic leader who is taking advantage of the political and religious conflict around him to grow his Church. The fact that he is Persian himself, and also stresses the need for loyalty to the state, makes it difficult to paint him as a dangerous radical. Meanwhile, he not only speaks and writes in Persian but knows the people, making it possible to craft his message directly to the Persian peoples. Furthermore, it doesn’t hurt that he is actually a rather brilliant writer and speaker.

[FN3] I think its safe to assume the Khavahd was terrified by the rebellion and acted vengefully in its aftermath as a result. These actions further reinforce the dynasty’s loyalty to Mazdakianism, and the Mazdakian loyalty to the dynasty. Although it effectively ends the rebellions, as nobles and priests now see the full extent of what awaits them if they rebel against the throne, but it also puts pressure upon those in the middle who may were alienated by the throne’s harsh actions.

[FN4] It would be very easy to simply make Abdul-Bari a clone of Muhammad. However, I think that would be cheating, considering that I’m pretty staunch in my butterflies. I hope that the biography I set out help set him apart from the historical template.

[FN5] I have been envisioning the Manichaens in Arabia since the beginning of the timeline and building up to their rise. From an early time, I felt that the faith that arose there would not be traditional Manicaenism, but a breakway sect that would better suit the conditions of Arabia. In some ways it’s a hybrid between the Manichaenism of OTL as well as early Islam. I hope that I have expressed this clearly and, if you want any further clarification, please ask. I will answer what questions I can and, if needed, will develop it further in a later post.

-----------------------------------------------------------------

All right, as promised, here is the new chapter

I thought, before we move forward in the Middle East, it would be good to focus a chapter on the religious developments of the region. As you will see in later posts, religion is going to play a huge part in the coming events, and it seems pertinent to spend some time reviewing what has happened and how these faiths have developed. As always, please feel free to share thought thoughts and concerns!