Chapter One Hundred and Twenty Seven: American Dreams and Mexican Prayers.

“If every country washed by the Caribbean Sea would show progress in stable and just civilisation…all question of interference by this Nation with their affairs would be at an end”.

The proposed text of the Roosevelt Corollary which President Theodore Roosevelt failed, ultimately, to turn into coherent US doctrine.

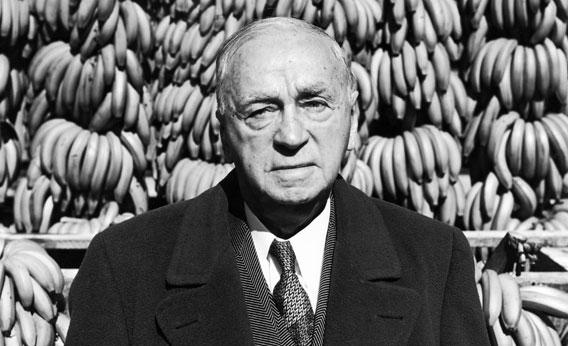

Sam “the Banana Man” Zemurray embodied, for many, the American Dream. He was the boundless ambition and achievement of the modern market personified. Born Schmuel Zmurri in the former Russian Empire, Zemurray’s family had emigrated in the 1890s to Alabama. Drawn inexorably to the mass marketplace of New Orleans, Zemurray made his money early in life by buying already ripe bananas off of the steam ships and selling them that day to grocers along the rail lines. By the turn of the century he already had some $100,000 dollars in the bank at the age of 23.

Sam Zemurray, head of United Fruit and Central American

power-broker

By the 1910s Zemurray had bought out the struggling United Fruit Company and turned it around into a huge business concern. United Fruit (Zemurray fired the board but kept the brand name) invested heavily in Central American fruit markets. Its steamers plied the Caribbean, its fruit was in every market across America, and its plantations were a gold mine. Zemurray, who had come from nothing as a store clerk in Selma, dined with Governors, Newspaper Barons, Socialites, and the Old Money families of Louisiana and the South.

He was also, from another perspective, everything that was wrong with American capitalism in the Caribbean. As United Fruit grew so too did its appetite and its reach. A constant battle for cheap and fresh fruit for the US market saw the company pursue ever more rapacious lines of business in Latin America. His use of bribery and intimidation, strong-arming local governments into line, saw United Fruit snap up prime land and lucrative low-tax deals. As the company grew, though, fuelled by consumer demand in the US, Zemurray turned to ever dirtier tactics. The hiring of corporate mercenaries, ostensibly as “Security”, led to repeated but unproven allegations that United Fruit were forcing poorer farmers and indigenous communities off land for cultivation, breaking up trade unions, and making sure that the process of cultivation ran smoothly. He even, on a number of occasions, directly sponsored coups against sitting governments, throwing company money and resources behind General Bonilla in Honduras (1911), Emiliano Vargas in Nicaragua (1916), and General Orella in Guatemala (1921). All three established corrupt, self-serving, soft dictatorships backed up by company funds.

The region was, like Zemurray’s bananas, over-ripe and ready to be plucked. A wave of protests over wages in Guatemala gave the Mexican Government an excuse to act. The Reyists in Mexico, under the leadership of revolutionary general turned President Enrique Gorostieta had spent over a decade consolidating power since they had triumphed over the pro-Communard regime in 1911. They had done so by mixing a modernising dictatorship, ironically building on the foundations of Porfiro Diaz laid in the 1900s, with fundamentally grass-roots Catholicism. The leading lights of the intellectual side of the Reyists, the clergy led by Archbishop Francisco Jimenez, realised early on that stamping out resistance relied to some extent on pulling together the forces of traditionalism and reform. Thus the legacy of the Cristeros became an authoritarian state rooted in traditional notions of Mexican culture, religion, and community. Land was reformed, creating vast swathes of peasant landowners who the regime hoped would become good conservative believers, and a sometimes uneasy balance of reform and stability settled over the country. Garbism, in the 1920s, made some inroads in the form of the Goldshirts but generally Gorostieta’s regime remained solid.

By the 1920s, however, a decade of stability and growth had begun to morph into a desire for action. “There is a feeling”, wrote the Spanish Ambassador in 1922, “that the new Mexico must flex its muscles”. The corruption of Central American Banana Republics and the grinding poverty there had already seen Reyist groups spread in Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Guatemala and it was rural protests in the last country that tipped Gorostieta to action.

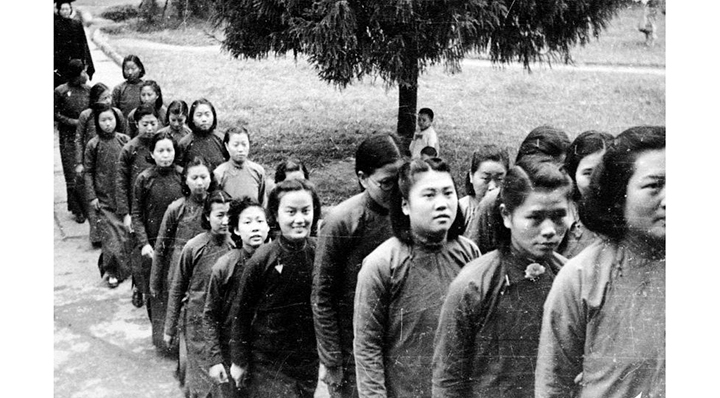

Mexican soldiers during the assault on Managua. A more modern army than any other force in

Latin America, they dominated their opponents within weeks of invasion.

Modernised with surplus equipment dumped onto the market by countries like Italy and Germany post-war through their factors in Venezuela, as well as British and American countries, the well-equipped Mexican army was far too much of a match for the underfunded parade-guard militaries of the Republics. They were welcomed with open arms by the oppressed poor of the region and as they went Mexicans nationalised the concerns of foreign companies like United Fruit. Guatemala City fell on the 13th May 1926, only seven days after the declaration of war. San Salvador was seized by rebels even before the Mexicans arrived on 22nd May and after some opposition Tegucigalpa’s resistance collapsed by mid June. The fall of Nicaragua by the end of August sent terrified alarm bells jangling through the entire US administration. Zemurray was frantically lobbying for intervention, along with dozens of other US companies, and, sitting atop a sizeable electoral majority and favourable ratings, the new President was inclined to act.

Nor, of course, was he alone. For in Communard Buenos Aires, alongside long-term exiles from Mexico itself, a small batch of Central American socialists had arrived to meet with delegates from the European Union.