Chapter Six

In the immediate outcome of the conflict with the Lombards, the priority of Maria was the reorganization of the conquered lands: not an easy task, considering they were territories which the Empire didn’t exercise its authority for not less of 150 years; plus she had to face the presence of Lombard persons which obviously hardly accepted to become Imperial subject, and the growing aspirations of the Italian Dukes which wanted to expand their power; lastly, there were the concerns of the Pope which didn’t want a penetration of the Greek rite in the freed lands, considering Italy as prerogative of the Patriarchate of Rome so under the Latin Church.

About the Orthodox presence in Italy, this was centred especially in the South, mostly in Sicily, Calabria, and Apulia, plus there was a relevant presence in Naples. In Central Imperial Italy, aside from Ravenna the population was predominantly of Latin rite; despite around the Imperial court were present Greek rite priests to cover its needs. The Church of Greek rite however didn’t have intention to usurp the role of the Latin priests, neither the Imperial authority felt the issue to impose the eastern church; it was essentially a presence obliged to cover the religious needs of the Greek-speaking population in the peninsula. However, in a South Italy where the Greek speaking population saw an exponential increase during the eighth century, also promoted by an Imperial policy of resettlement (for example, the Anatolian army operating in Apulia settled permanently here and integrated into the Tagmata of that duchy), the role of the Eastern Church started to compete more actively with the Catholic one.

Maria, taking opportunity of the death of Scolastico during 726, pushed by the Southern Italian Dukes, decided however to “suspend” the title of Esarch of Italy, as unnecessary for the moment considering the peninsula was enjoying the presence of the Emperor. Constantine V at the time was eight, but Maria felt he was enough ready to start to assist the various councils and to be more active in the political life of the Empire, so despite she still hold the regency, she started to associate the son to his growing duties. The suspension of the title of Esarch wasn’t so exactly appreciated by the Dukes of Rome and Naples which wanted the title for themselves, but were more than appeased by the new territories they obtained under their administration and above all by the deconstruction of the Ravennate territory. In fact, Maria appointed as successor of Scolastico a man loyal to her, Paul, but as “Duke of Ravenna”. In fact, to the now former Esarchate were stripped all the territories south of Rimini, as the Imperial corridor and the “Maritime Pentapolis” became two new duchies, seated in Perugia and Ancona respectively. Maria thought in a first moment to reorganize the Italian Duchies in Themes, but due to the persisting Lombard menace Imperial Italy wasn’t ready yet to pass from a military to a civilian administration so she desisted from that project. In the south, aside from the expansion of the Roman, Neapolitan, and Apulian Duchies, the most relevant change was the introduction of the Duchy of Lucania, with the site of Anglona (1) as capital.

The only Italian Theme at the time was the Sicilian one, the most prosperous and vital for the Byzantine in Italy: but between 727 and 728 a relevant disaster incurred to the Empire: the Arab invasion of the western part of the island. The invasion was prepared by the treason of Eusebius of Messina, which in 823 attempted to seize Sicily for himself, but failed and escaped in Ifriqiya, where he asked the help of the Arabs.

The Muslims saw a chance to finally get control of the island, launching a great amphibious invasion at Mazara del Vallo; from there, they got control of a relevant part of the island; and as Eusebius died in 828 during a siege, the invaders didn’t felt anymore obligations of sort to build a puppet state and declared open the path for the integration of Sicily into the Islamic world.

The Byzantines however in the end managed to counterattack with the support of reinforcements coming from Calabria, preventing the fall of Syracuse and keeping control of East Sicily, but the West for the next three centuries remained in Arab hands.

The consequences for the Empire were dragged for a long time: above all allowing for the Arabs to commit periodical raids on the Italian shores for decades, and in the immediate period losing a relevant part of income and manpower necessary for the Byzantines to keep their grip on Italy. As for Maria’s regency, the loss of West Sicily signed its lowest point, in the light of a certain decision taken which if turned down could have preserved the island to be invaded.

In fact, the Duke of Aquitaine, Odo I, was rather busy to face the Iberian Muslims pointing at the South territories of his domains; and asked the support of the Byzantines to cover his back in the Mediterranean. The Pope pushed to help the Duke, so Maria agreed to send a part of the Imperial navy in Italy in direction of recently occupied Septimania raiding its coasts. The raiding was supposed to be a preliminary action to prepare the invasion of the region, prelude for a more ambitious plan to retake the Balearic islands, but the plan was cancelled after the news of the Arab invasion, aided also by the openings left by the Byzantine navy. Still, the raid allowed Odo I to gain still more time against the Muslims and for Maria to gain some additional money which compensated for quite time the loss of West Sicily; plus it contributed to increase the ties between Papacy and Imperial court and still for the latter to restore a diplomatic connection in Gallia, albeit at the time only with Aquitaine.

However, the campaign in Septimania naturally didn’t compensate the situation in Sicily, so things started to become more tense in Imperial Italy, especially in the Duchy of Ravenna were Paul fatigued to impose his authority in a region which hardly tolerated to have lost its predominant role in the peninsula, so many started to look with crescent hope towards Liutprand. Various frontier outposts defected in favour of the Lombard King, and after a rejected ultimatum from Rome to return those territories, war was inevitable.

Liutprand believed to have better chances respect to the previous conflict, considering the Byzantines were busy with the Sicilian situation at the time; but the forces here involved were mostly coming from Calabria, and only a part of the effective Imperial armies. Still, the Lombard King also hoped in a reaffirmed loyalty from Spoleto and Benevento to keep busy the Byzantines in the South of Italy.

The situation went initially well for the Lombards: mostly of the Duchy of Ravenna was invaded, and the same city revolted and the angry mob killed Paul; still, the city refused to submit to Liutprand, its hope being to resist to convince the Dowager Empress to restore the Esarchate. Maria however gave mandate to Eutychius, one of her most prominent courtiers, the duty to recover the lost ground and at the same time quell the Ravennate riot. On that front, Eutychius managed in 728 to retrieve back Ravenna, quelling the revolt.

More urgent for the Byzantines was the situation in Central Italy, where Liutprand seized the fortified outpost of Narni in another tentative to split in two the Byzantine territories, and then seemed oriented to attack directly Rome. At that point however intervened as mediator Gregory II, which decided to meet directly the Lombard King in Sutri, city in the middle of contested land between the two factions, but outside the jurisdiction of the Duchy of Rome at the moment; Maria approved initially the move at least to allow her to gain time to prepare Rome from an eventual siege, but the outcome of the encounter went differently as she expected.

Liutprand in fact in the attempt to buy Gregory to his side, he agreed to “donate” Sutri and its surroundings to the Pope of Rome, so allowing the Catholic Church to be the de facto owner.

Gregory II showed to largely appreciate the donation, obtaining also promises to keep in peace Rome; but Maria was rather infuriated, believing the Bishop of the Eternal city sold the Empire to the Lombards, so she acted rather harshly towards him: she didn’t depose him, but she refused to allow him to return in Rome until he turned the Lombard donation to the Empire. Gregory then settled temporally in Sutri, administrating the affairs of the Roman Dioceses from that site.

For the historians, Gregory accepted the donation not for a betrayal against the Empire, but more to force it to take a definitive stance over the control of territorial possessions for the Church into Imperial territories, while attempting to pass as “saviour of Rome”. However his plan backfired as he received few support from the various Catholic Bishops of Italy, the Imperial ones mostly agreeing with Maria and the Lombard ones irritated for the concession received to him by their king. At the same time, Maria didn’t break definitely with Gregory as she didn’t want a possible insurgence of the Latin Christians against the Imperial authority in those dire times. Besides, it was proved there was a correspondence between Sutri and Rome at the time to seek a possible solution to the matter.

Liutprand however, as remained loyal to the word to not invade Rome, however moved into Central Italy, gobbling most of the Duchy of Perugia, but failing to take the provincial capital. In the meanwhile, in Longobardia Minor things really turned bad for the Lombards. The Beneventine in fact failed to contain a joint invasion from Naples and Apulia (where the Anatolians were unarrestable) in its southern territories, forcing to cede all the territories East and South of the Ofanto river, and fatiguing to hold the Byzantines on the : a third of their remnant territory from the last war was lost to the Empire. The Duchy of Benevento in fact underestimated the Byzantine strength in South Italy especially after the Sicilian situation, and overestimated its capacities, not believing in an enemy offensive in that direction.

But aside from the turmoil in the Ravennate lands and the Sicilian situation, the Empire remained compact behind Maria and Constantine, the ties with Germanus and Artavasdos hold allowing the Dowager Empress to receive another surge of reinforcements from Constantinople, Anatolia and Greece during 728.

Those reinforcements were rather useful for example to Eutychius, which after having restored order to Ravenna (forced to pay an harsh tribute, with a relevant part of its wealth forced to take the road to Rome) aided the forces of the Duchy of Ancona to invade the regions north of the Chienti River of the Duchy of Spoleto, and only hardly Thrasimund II managed to preserve the control of the site of Foligno, at the time still more known as Fulginium. However, sensing a sudden weakness of the Royal Lombard power in Langobardia Minor, he made a deal with Eutychius to accept a peace with the Empire accepting the loss of territory in exchange of his will to declare independence from the Lombard Kingdom. Eutychius was rather conflicted, because if he recognized the independence of Spoleto it will surely weak the Lombards, but at the same time it will make more difficult for the Empire to retrieve the same Duchy; but it accepted nevertheless to focus his efforts in the Duchy of Perugia.

The peace made with Spoleto brought the Duchy of Benevento to offer peace terms to the Empire as well, ceding everything East to the Ofanto (the main loss being Bari), but reaffirming its loyalty to the Lombard Kingdom. Liutprand was rather enraged over the new act of defiance of Spoleto and the separate peace of Benevento, so his last hope to win the war was to conquer for entire the Duchy of Perugia. In effect during 729 he managed to provoke the fall of the city, allowing him to proceed into Spoleto, taking also that city; but Thrasimund escaped in direction of Ancona, where he forged an alliance with Eutychius and started to prepare the liberation of his Duchy; meanwhile, to further ensure his decision to make Spoleto an independent country, he obtained the support of the Pope granting on the path of the Donation of Sutri some territories to be administrated directly by the Bishops of Rome.

The fall of Perugia convinced Maria of the necessity to reach an agreement with Gregory II, albeit only in 730 a definitive solution was reached. From now on, the Church of Rome (intended in its entirety) could have the possibility to administrate directly territories into the Empire only after a definitive recognition from the Imperial authority, but only if accepting to rule them in name of the Empire. In substance, the Church obtained the use of a certain territory and the privilege to pass over its successors ( from a bishop the use passed to the next bishop in solution of continuity), but not the possession as it remained in hands of the Empire. At the same time, the Empire will not respond over Ecclesiastic territories outside the Empire and above all outside of Italy. It was so determined a double formula (de jure administration to the Church, de facto possession to the Empire) which in the intentions of both Maria and Gregory II should have take place the successive relations between the Roman Church and the Empire, albeit in the next centuries the growing tendency towards feudalism across Europe which didn’t spare Imperial Italy made the boundaries of that agreement more weak and contestable.

However, Gregory II returned in Rome, Sutri being formally integrated into the Empire but under control of the Pope, and Maria felt enough reassured of the loyalty from the Latin Church to continue the war with the Lombards. The war continued with alternate skirmishes until in 732, the unexpected happened when a Lombard army leaded by the nephew of Liutprand Hildeprand and his lieutenant the Duke of Vicenza Peredeus managed to conquer Ravenna, sacking it. As Eutychius was still busy in Central Italy along with the Duke of Perugia Agathon, it seemed the Byzantine rule in Central Italy was to be overthrow, but at that point intervened the unexpected support of the Duchy of the Maritime Venetia.

The Maritime Venetia was what remained of Imperial Venetia around the territory of the lagoon which brought its name; a small area, but becoming a rather prosperous one due to the settlements risen in the various islands into the same lagoon, fruit of the refugees escaped from the inland territories to seek refuge towards the barbarian invasions. As the Venetian region didn’t lost with the barbarian invasion the role of trade crossroad, the people of the lagoon prospered due to their commercial affairs while remaining under the Imperial protection; still, they always felt the competition with Ravenna, which wanted to keep the region under its grip. When however the coastline north of the Delta of the Po was lost to the Lombards, the ties with the exarchate started to loosen and the Venetians asked for more autonomy, obtained by Constantinople in 697, despite the Esarchate obtained right to influence its internal policies. So it was formally created the Duchy of Venetia, more known as Dogato di Venezia from the transliteration of the local dialect.

It was remembered however despite 697 was recognized as conventional birth date of the Dogato, Venezia proper didn’t exist yet; the most prominent settlements at the time were the towns of Eracliana and Equilio on the Eastern side of the lagoon, in constant rivalry to impose their own candidate to the guidance of the territory. In fact, despite the islands in the central part of the Lagoon were surely more safe, however at the time weren’t enough desirable for the rise of a trade hub. Still, there was a small town called Rivoalto, which was no more than a fishing post and an intermediate point of travel towards more relevant settlements in the Lagoon. It will occur other 120 years since the foundation of the Duchy before the town will take its rightful place in history…

Anyway, the third Duke of Venetia, Ursus, leaded his forces to the liberation of Ravenna, striking an impressive blow to the Lombards: not only they were badly defeated, but Peredeus died in battle and Hildeprand was caught as prisoner. The liberation of Ravenna however brought further devastation to the city,

It was the signal of the Byzantine decisive counterassault. Helped by the fact Liutprand turned after the fall of Spoleto towards Benevento, forcing the Duchy to resume the fight (which created more dissent in the local nobility and clergy which wanted peace instead), supported by the armies of Ursus and Eutychius Agathon managed to liberate Perugia, and from there moving towards Spoleto.

Liutprand found himself suddenly surrounded, so his only choice was to open his path towards Langobardia Maior with the force. Moving again into the Duchy of Spoleto, he was however intercepted in the September of 732 at the outskirts of the Fucino Lake; because of defections within his ranks of elements from Langobardia Minor, he obtained a crushing defeat. The Lombard King managed somehow to disengage from the Imperial armies and return in Benevento, but he found the city in a near state of turmoil, as the populace wanted peace being exhausted from the war.

Liutprand agreed then to open negotiations with the Byzantines, recognizing his defeat. As in the preliminary peace negotiations obtained the permission to move his army to Langobardia Maior, however Maria pretended from him to formalize the definitive treaty in Sutri, for two main reasons: to humiliate him in the town he decided to cede to the Pope in the attempt to create a strife between the Church and the Empire, and also to praise the Papacy of Gregory III which was surely more loyal (he was a son of a Syrian, so more open towards the Greek Emperors) and supportive (he contributed through the various Italian Bishops to keep open the communications between Ursus and Eutychius after the fall of Ravenna).

In the “Peace of Sutri”, confirmed at the start of 733, Liutprand was forced to agree over those conditions:

To recognize the cession to the Empire of all the territories of the Duchy of Benevento South and East of the Ofanto. Said Duchy however will be still part of the Lombard Kingdom;

To recognize the independence of the Duchy of Spoleto. Thrasimund II will be the rightful first ruler of the independent country, but for his independence had to confirm to cede to the Empire all the territories North of the Chienti river;

To return the territories occupied in the Duchy of Ravenna, and to cede the Southern tip of the Duchy of Tuscia. In fact, after Sutri, the army of the Roman Duke to consolidate the safety of Rome started the invasion of said country, taking during 731 the town of Orvieto.

To pay a ransom for the release of the Lombard prisoners; Byzantine prisoners will be immediately released.

To worse the position of Liutprand, he was informed of the death of his daughter, so he was deprived of the only card he could have used towards Maria to sweeten his position. The Lombard King returned in Pavia, but rather demoralized – his dream to unify Italy was practically vanished, and his Kingdom rather shattered.

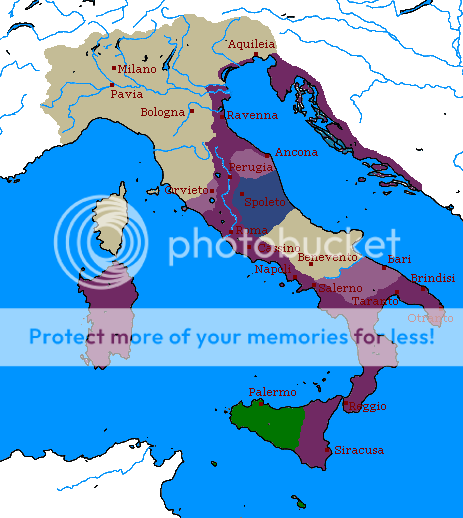

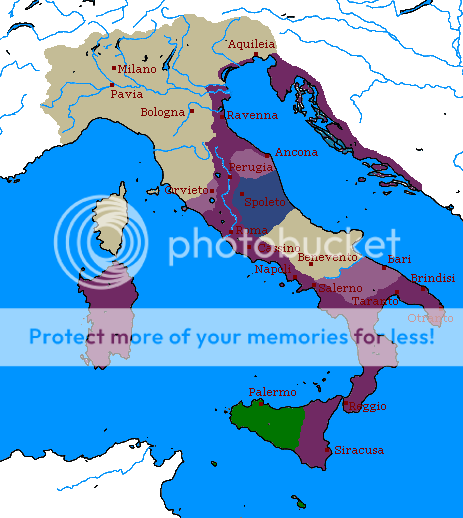

Italy in 733. Despite the Arab invasion in West Sicily (dark green), the Empire (dark purple) stripped to the Lombards (grey) various territories (light purple), while putting in jeopardy the entire Langobardia Minor with the independence of Spoleto (blue)...

Italy in 733. Despite the Arab invasion in West Sicily (dark green), the Empire (dark purple) stripped to the Lombards (grey) various territories (light purple), while putting in jeopardy the entire Langobardia Minor with the independence of Spoleto (blue)...

So it ended the “second phase” of the last barbarian war. The Eastern Roman Empire came out further reinforced in Italy, albeit rather exhausted not less of the Lombards; but the Papacy resulted more strong as well, as Sutri despite initially was seen as a false step towards the Empire, in the end delineated the basis of its power across Western Europe in the successive centuries…

However, the optimism in the Imperial territories was quite high: despite the loss of half of Sicily burned still, on the other side the Lombards were in full decline and the Imperial authority going towards the recovery of Italy. Plus Constantine was soon reaching adulthood and able to proceed towards the path of healing of the Empire started by his mother, starting with his eventual return in Constantinople.

However, those expectations will have soon to face a more harsh reality...