Space station Liberty (5)

Archibald

Banned

December 9, 1979

Enterprise was sighted by the crew. Pogue had the Jacksons Can you feel it playing on Liberty's tape recorder. The Agena Lidar approach system began homing on Liberty's aft port, and Liberty's crew retreated to Hyperion so that they could escape in the event the module got out of control.

About 200m out, the Agena lost its lock on Liberty's aft port antenna. Sally Ride watched from within Hyperion as the Enterprise-Agena duo passed within 10m of the base block. Under control from the ground the stack backed by 400 km before a second attempt, which worked perfectly.

Ride then used the Canadarm to catch the module and move it to a side docking port. The axial port was home of Helios or Agena resupply vehicles. The manoeuvre would be repeated three times on the decade; this way Endeavour, Atlantis and Discovery would be added to Liberty.

And there were the Telescope mount borrowed from the never-flown Skylab B. Incoming modules would also carry a small centrifuge. For NASA it was another occasion to prove that its cherished and expensive station could produce valuable science.

***

March 12 1980

Music: Barry White, Let the music play

The mobile launch tower and the surrounding shelter had been pulled away, and a bit of light fell on the cabin. Above their heads, Helios hatches had been closed and their was not many things to be seen nor done. Ralf Blueford glanced at the cabin. It was not very different from the Apollo environment or trainers he had experienced over the years, although it was much roomier. The commander and copilot sat side-by-side in what had been, twelve years before, Gemini. Ralf Blueford and a fellow astronaut sat behind them, into the new “passenger section” grafted to the old capsule. Behind them was the heatshield, with the hatch dug trough it to the cargo section – another difference with the old Gemini, it made Helios a “poor man’s space shuttle” in the words of some disappointed Johnson employees and astronauts.

Blueford disagreed with them.

The enhancements McDonnell Douglas had applied over the years had turned Helios configuration into a flexible, robust space truck. Yeah, a truck: that’s the thing. Outwardly the ship that stuck on top of the Titan superficially looked much the same as old Geminis which had flown in the 1960s; however it was a leap forward, a true Earth-orbital ferry. There were no windows to look through, and even Helios pilots had reduced view – far from the airliner cockpit promised by the shuttle years before. Helios used an off-the-shelf launch escape system borrowed from Apollo.

…

At T minus zero, Ralf Blueford actually felt ignition of Titan solid rocket motors – there was a violent jolt, and the booster cleared the launch tower rapidly. The first stage engines awoke 110 seconds into the flight, briefly adding their thrust to the dying SRMs. There was a loud bang as the connections to the solids were severed; a fiery orange glow surrounded the cabin. Titan first stage – the solids being stage zero - burned for two minutes, providing a softer ride than the SRMs.

G-forces grew steadily, and suddenly there was a series of vibrations and jolts. Stage 2 had fired directly into stage 1, smashing it to bits. This brutal approach was typical of Titan and a marked contrast with Saturn stages and interstages detaching and falling in slow motion, as seen in an iconic Apollo movie.

Eight minutes into the flight explosive bolts severed the spent second stage from Chronos. Just like every Mercury, Gemini and Apollo before it, each capsulebear a name chosen by its crew. The Titan III had delivered the capsule into a 160 miles high orbit, to be progressively raised to Liberty heights in the next hours.

Ralf Blueford and its crewmates were to relieve Sally Ride and Thomas Mattingly, who had spent 200 days in space. Since Skylab days record durations flights were the object of a fierce competition between NASA and the Soviets. Late 1974 the Skylab 4 mission had lasted 84 days, a record that had hold for three years.

Then soviet crews gradually extended their stays into their OPSEK-Mir – from 95 to 180 days late 1979. NASA, which needed to show the usefulness of Liberty to a reluctant Carter administration, welcomed the soviet challenge. Ride and Mattingly had just broken the record. Liberty’s core was notably roomier than the soviet Salyuts, even after a second Salyut had apparently been added to the first.

Helios now started to chase Liberty across the sky. It took a complete day to bring the capsule close from the station. And suddenly it was there, a complex construction of metal floating in space. The crew had Bette Davis Eyes playing on their tape recorder, as background. Docking would be manual; NASA astronauts had heavily insisted on this point, although a fully automated system existed for the Agenas. Manual docking was an heritage from Apollo. The docking ring was, ironically, a present from the Soviets after the Apollo Soyuz Test Program.

As the capsule get closer from the station base block, Ralf Blueford had a delicate mission to accomplish. He unstrapped, and floated to the rear of the reentry module, in the direction of the heatshield. There was the hatch which gave access to the cargo block. Needless to say, the hatch and its seals were thick, robust, and had been tested in the worst reentry scenarios back in 1973-74.

Ralf Blueford floated through the cargo block. Its destination was a control station located at the rear. From there, he would visually monitor docking to Liberty. He would obviously be in radio contact with Mattingly and the ground during the manoeuvre. He entered the small cabin and carefully strapped itself to the seat. “”Hello Tom !” he contacted Mattingly “Look at me, the space crane operator.” Now let’s dock this thing for real he muttered for himself.

Unlike Apollo, Helios docked backward. Control of the spacecraft had been transferred from the reentry module to Ralf Blueford. He was now piloting Helios toward space station Liberty. Step by step, acting on the thrusters and RCS, talking to the station crew and to the ground, he get closer and closer. “Contact !” a small vibration shaked the capsule “Excellent ! Smooth as air”.

…

His crewmates were now shutting systems in the reentry module, transferring power to the cargo block, preparing for transfer to the station. They joined Ralf Blueford near the second hatch, the one giving access to Liberty.

Mattingly and Ride warmly welcomed the crew. They progressed through the station central tunnel, to the crew quarters. There were room aplenty, even more than in Skylab. Coming after Helios cramped quarters, the base block looked immense, smart and comfortable.

The four crew quarters were true little motel room, each with its own bunk, a personal desk and locker facilities. There were hot and cold water, refrigeration and cooking facilities. A hygiene unit enabled the crew to wash and shower. And, above all, were the toilets. Gone were Apollo horrendous waste collection bags that the astronauts had to… glue to their buttocks.

For the first time were five people in Liberty. And the number would grow over the years. The space station had better to be comfortable – yet comfort in space had a tortuous history. Back in the mid-60's Apollo was anything but comfortable; fortunately astronauts spent a maximum of two weeks in space.

Skylab, however promised to be different.

In 1967 manned spaceflight czar George Mueller took a strong interest in the orbital workshop (not Skylab yet !), especially the layout of the living quarters. Looking at the mockup, Mueller was appalled by the barren, mechanical character of the workshop interior. "Nobody could have lived in that thing for more than two months," he said of it later; "they'd have gone stir-crazy." Expressing this concern to Skylab managers Lee Belew and Charles Mathews, he suggested that an industrial design expert be brought in to give the workshop "some reasonable degree of creature comfort.

For the habitability study, Skylab contractor Martin Marietta chose one of the best known industrial design firms in the world-Raymond Loewy/William Snaith, Inc., of New York. Loewy, a pioneer of industrial design in the United States, had worked on functional styling for a variety of industrial products for forty years, besides designing stores, shopping centers, and office buildings.

Approaching his 75th birthday in 1968, Loewy had reduced the scope of his own professional activity somewhat, but he took a personal interest in the workshop project. Loewy produced a formal report in February 1968, citing many faults in the existing layout and suggesting a number of improvements. The interior of the workshop was poorly planned; a working area should be simple, with enclosed and open areas "flow[ing] smoothly as integrated elements . . . against neutral backgrounds." While they found a certain "honesty in the straightforward treatment of interior space," the overall impression was nonetheless forbidding.

The basic cylindrical structure clashed with rectangular elements and with the harsh pattern of triangular gridwork liberally spread throughout the workshop. The visual environment was badly cluttered. Lights were scattered apparently at random over the ceiling, and colors were much too dark. This depressing habitat could, however, be much improved simply by organized use of color and illumination.

Loewy recommended a neutral background of pale yellow, with brighter accents for variety and for identifying crew aids, experiment equipment, and personal kits. Lighting should be localized at work areas, and lights with a warmer spectral range substituted for the cold fluorescents used in the mockup. Loewy recommended creating a wardroom-a space for eating, relaxing, and handling routine office work-and Martin's engineers concurred. Better yet, the floor plan should be made flexible by the use of movable panels, so that different arrangements could be tested. Evaluating a single layout was not a good way to acquire information about the design of space stations.

Mueller was pleased with Loewy's work, and a new contract was drawn up engaging the firm through 1968. By now Houston was taking greater interest in the crew quarters, and the new Loewy/Snaith contract specifically provided that the consultants would work with the principal investigator for Houston's habitability experiment.

By September 1969 George Mueller was concerned that Huntsville was not acting on Loewy's ideas, so he called a meeting on habitability for mid-October. The meeting principals (including Raymond Loewy, who came at Mueller's invitation) met in Washington on 14 October for a general review of the habitability support system. Mueller left the clear impression that he was not satisfied with the handling of crew quarters. During the day all aspects of habitability were discussed, including some that had major impact on the workshop structure. Both Loewy and Johnson had suggested rearranging the floor plan to provide a wardroom; both had also endorsed adding a large window to allow the crew to enjoy the view from orbit, something that had been impossible in the wet workshop. The wardroom was easily agreed to, but the window created an impasse. While everyone agreed that it would be very nice to have, Belew pointed out that a window posed one of the toughest problems a spacecraft designer could face. It was too costly, it would weaken the structure, it would take too long to develop and test, and it was not essential to mission success. Counterarguments could not rebut his position.

Finally, Mueller asked Loewy for an opinion. The response was unequivocal; it was unthinkable, Loewy said, not to have a window. Its recreational value alone would be worth its cost on a long mission. With that, Mueller turned to Belew and said, "Put in the window." Schneider formally authorized the window and the wardroom, along with several other changes.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Iron Curtain, G alina Balashova was at work on Soyuz interior partitions. Balashova was a woman and an architect, working for OKB-1 on the space program. That made her a pretty unique recruit, but Korolev needed his work to make the Soyuz habitable. For the record Apollo was pretty unlivable: it famously lacked something as basic as a toilet, with astronauts shitting in plastic bags glued to their ass, a system so horrible that the Apollo 12 crew prefered eating a boatload of immodium rather than using it. By contrast the smaller Soyuz was far more liveable. Korolev had added a living quarter atop the reentry capsule, and Balashkova had been tasked to make it pleasant to live, tackling things like spatial proportions, the psychological effects of colors or the functional distribution of technical equipment.

In the mid-70's the architects were once again called to the rescue for both Liberty and MKBS-1 large space stations. Raymond Loewy was definitively too old, but he passed the torch to an extremely gifted young artist, John Frassanito.

On the soviet side, Balashova was tasked to make the future MKBS-1 an habitable place. With the core module 22 ft in diameter, Balashova main issue was to make that enormous volume an habitable place. Unbestknown to her Frassanito was facing similar issues with the american space station; the core module was even wider than either MKBS-1 or Skylab, a good 33 ft in diameter.

While Frassanito had switched to computer design at the Datapoint company, he agreed to work part-time for NASA on Liberty interior design (which included some Datapoint computers, by the way).

Frassanito sought to apply Loewy Skylab lessons to Liberty

• Each astronaut should be allowed eight hours of solitude daily. (this concept led to the first private rooms in a spacecraft)

• Astronauts would be secured for meals facing each other, in a triangular layout. There were three crew members, and Loewy's layout prevented any hierarchal table-seating issues that could cause tension.

• Partitions would be smooth and flush to facilitate cleanup after the inevitable bouts of space sickness.

Where every other space station module ever built is laid out internally like, say, a trailer, longways, with a floor and a ceiling running longways down the pressurized cylinder, Skylab was arranged more like a skyscraper, a pattern Liberty followed and improved. That means vertically, with actual "decks" or floors of open metal framework set into it. There were two main habitable floors, with an additional module for the solar telescope array. The "upper" main module floor had so much room that it was used for indoor testing of a prototype NASA spacewalking mobility backpack.

Balashova once painted murals for the interior of the Soyuz habitation module. She chose a winter landscape from her home city of Lobyna, the view from her apartment, and the summertime beach in the Black Sea city of Sudak, among other scenes. She did the same for the MKBS-1 interior, albeit on a very different scale. Notably, Balashova integrated a lack of gravity into her design, choosing dark colors for the floor and bright colors for the ceiling. There was an important psychological effect to this, given that astronauts, so accustomed to life on Earth, would be less likely to get disoriented inside the Soyuz's habitation module. Balashova was also responsible for lighting and furnishing design, including living areas, a cabinet equipped with a bookshelf and a folding table, all with a range of colors intended to improve human orientation in zero gravity.

...

April 12, 1980

Ken Mattingly and Sally Ride returned to Earth. Crew awoke to Chicago If you me leave now.

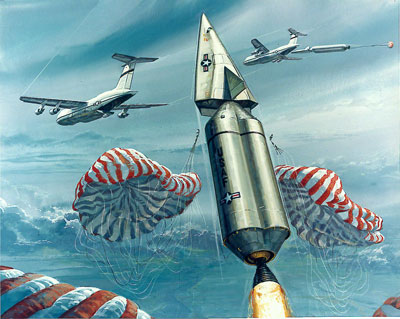

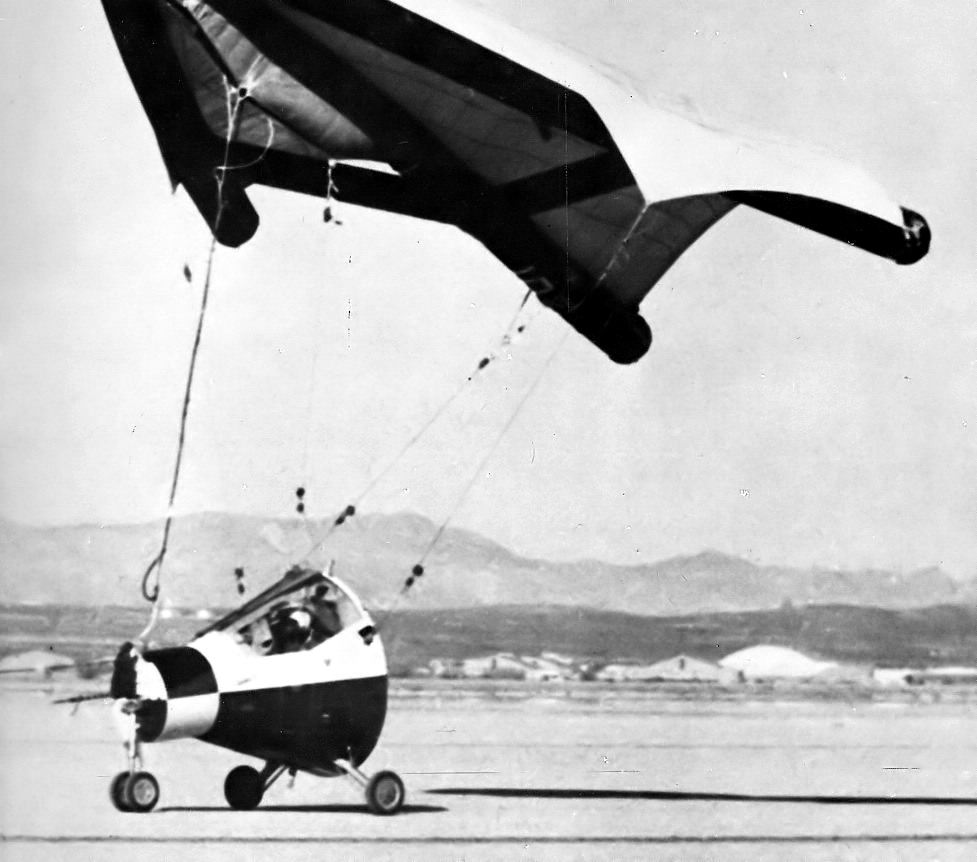

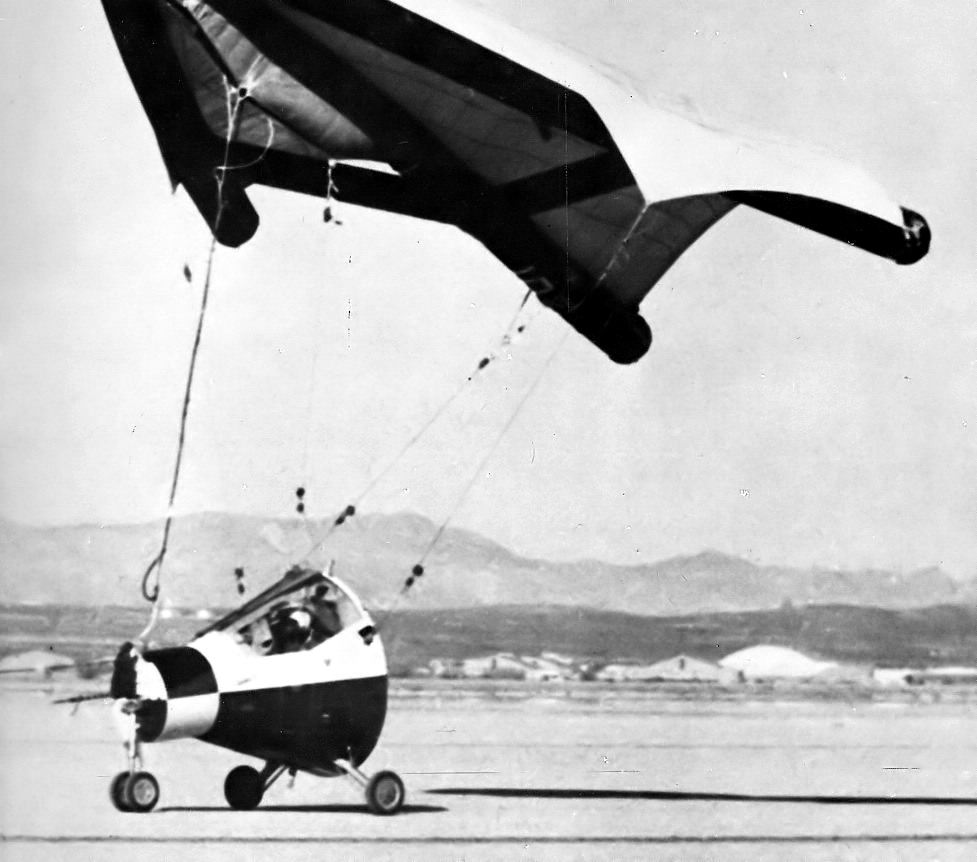

They carefully closed the controversial access hatch through their heatshield and undocked. Later they jettisoned the large logistic module and the adapter. Their capsule reentered ass-first, ablating the heatshield. Still high in the atmosphere, a small chute sprouted of the nose, turning the capsule into a nose-first attitude, ready for the next step: the parafoil deployment.

Unlike Apollo they had an horizontal ranging capability instead of simply following the wind as in a conventional parachute. They we are able to maneuver even into the wind through developing an airplane-like lift on their canopy. It enabled Helios to maneuver even in the presence of high -winds to a preselected point for landing.

Mattignly changed the relative attitude of the spacecraft and the parachute through a system of line pulls. Using this mechanism he could roll the spacecraft, or move it on ahead or bring it in short.

They had control capability for about 20 to 30 miles of range with the lifting canopy alone. Together with the offset center of gravity in reentry Big Gemini could maneuver an extra hundred miles for a grand total in the neighborhood of a hundred and twenty miles - not bad, but a mere 5 percent of the lost space shuttle 1500 miles crossrange. The Big G parawing was sensitive to bad weather, and strategies had had to be invented to bring the spaceship down to Earth in a reasonable time even with uncooperative weather.

The operational approach with a system like this was just what NASA did on Apollo 9 — the crew would wait to deorbit, going another orbit around and changing their reentry point. As such NASA had selected a network of alternate landing sites.

Low inclinations flights had a row of very good landing sites across the Southern United States which gave crews the ability to land several places between the west coast and the east coast. Four sites were prime recovery sites. With an adequate number of passes weather was never a true issue - that, and Big G reentry module was small, light and seldom reused, so bringing back to the Cape was hardly an expensive priority. It was fortunate, because the module width of 14 feet mandated a Supper Guppy or a C-133 large-diameter cargo aircraft... or a Sikorsky CH-54 Skycrane helicopter !

As for higher inclinations orbits -recovery sites used locations in the whole United States. The parawing developped a lifting force that allowed landings with a good enough precision — although not at a place like Los Angeles International Airport, but certainly at places like Palmdale, Edwards, White Sands, or Green River.

They were now floating a mile above Florida, on clear skies with very little winds and a superb view of the space coast. There, NASA and the Air Force shared a narrow penninsula. They flew over the deserted Merrit Island Launch Complex 39 gantries, over the big cube that was the Vehicle Assembly Building. But they would not land there; north of the VAB stood an empty, rough patch of land that had never been turned into a space shuttle landing strip.

Mattingly instead guided the capsule to the military area, to Cape Canaveral Air Force station. After a gentle touchdown, Big Gemini wheeled down to a perfect stop on the military airfield, the so-called skid strip.

(Yes, I wanted wheels, not skids, on Big Gemini, cute little wheels)

Enterprise was sighted by the crew. Pogue had the Jacksons Can you feel it playing on Liberty's tape recorder. The Agena Lidar approach system began homing on Liberty's aft port, and Liberty's crew retreated to Hyperion so that they could escape in the event the module got out of control.

About 200m out, the Agena lost its lock on Liberty's aft port antenna. Sally Ride watched from within Hyperion as the Enterprise-Agena duo passed within 10m of the base block. Under control from the ground the stack backed by 400 km before a second attempt, which worked perfectly.

Ride then used the Canadarm to catch the module and move it to a side docking port. The axial port was home of Helios or Agena resupply vehicles. The manoeuvre would be repeated three times on the decade; this way Endeavour, Atlantis and Discovery would be added to Liberty.

And there were the Telescope mount borrowed from the never-flown Skylab B. Incoming modules would also carry a small centrifuge. For NASA it was another occasion to prove that its cherished and expensive station could produce valuable science.

***

March 12 1980

Music: Barry White, Let the music play

The mobile launch tower and the surrounding shelter had been pulled away, and a bit of light fell on the cabin. Above their heads, Helios hatches had been closed and their was not many things to be seen nor done. Ralf Blueford glanced at the cabin. It was not very different from the Apollo environment or trainers he had experienced over the years, although it was much roomier. The commander and copilot sat side-by-side in what had been, twelve years before, Gemini. Ralf Blueford and a fellow astronaut sat behind them, into the new “passenger section” grafted to the old capsule. Behind them was the heatshield, with the hatch dug trough it to the cargo section – another difference with the old Gemini, it made Helios a “poor man’s space shuttle” in the words of some disappointed Johnson employees and astronauts.

Blueford disagreed with them.

The enhancements McDonnell Douglas had applied over the years had turned Helios configuration into a flexible, robust space truck. Yeah, a truck: that’s the thing. Outwardly the ship that stuck on top of the Titan superficially looked much the same as old Geminis which had flown in the 1960s; however it was a leap forward, a true Earth-orbital ferry. There were no windows to look through, and even Helios pilots had reduced view – far from the airliner cockpit promised by the shuttle years before. Helios used an off-the-shelf launch escape system borrowed from Apollo.

…

At T minus zero, Ralf Blueford actually felt ignition of Titan solid rocket motors – there was a violent jolt, and the booster cleared the launch tower rapidly. The first stage engines awoke 110 seconds into the flight, briefly adding their thrust to the dying SRMs. There was a loud bang as the connections to the solids were severed; a fiery orange glow surrounded the cabin. Titan first stage – the solids being stage zero - burned for two minutes, providing a softer ride than the SRMs.

G-forces grew steadily, and suddenly there was a series of vibrations and jolts. Stage 2 had fired directly into stage 1, smashing it to bits. This brutal approach was typical of Titan and a marked contrast with Saturn stages and interstages detaching and falling in slow motion, as seen in an iconic Apollo movie.

Eight minutes into the flight explosive bolts severed the spent second stage from Chronos. Just like every Mercury, Gemini and Apollo before it, each capsulebear a name chosen by its crew. The Titan III had delivered the capsule into a 160 miles high orbit, to be progressively raised to Liberty heights in the next hours.

Ralf Blueford and its crewmates were to relieve Sally Ride and Thomas Mattingly, who had spent 200 days in space. Since Skylab days record durations flights were the object of a fierce competition between NASA and the Soviets. Late 1974 the Skylab 4 mission had lasted 84 days, a record that had hold for three years.

Then soviet crews gradually extended their stays into their OPSEK-Mir – from 95 to 180 days late 1979. NASA, which needed to show the usefulness of Liberty to a reluctant Carter administration, welcomed the soviet challenge. Ride and Mattingly had just broken the record. Liberty’s core was notably roomier than the soviet Salyuts, even after a second Salyut had apparently been added to the first.

Helios now started to chase Liberty across the sky. It took a complete day to bring the capsule close from the station. And suddenly it was there, a complex construction of metal floating in space. The crew had Bette Davis Eyes playing on their tape recorder, as background. Docking would be manual; NASA astronauts had heavily insisted on this point, although a fully automated system existed for the Agenas. Manual docking was an heritage from Apollo. The docking ring was, ironically, a present from the Soviets after the Apollo Soyuz Test Program.

As the capsule get closer from the station base block, Ralf Blueford had a delicate mission to accomplish. He unstrapped, and floated to the rear of the reentry module, in the direction of the heatshield. There was the hatch which gave access to the cargo block. Needless to say, the hatch and its seals were thick, robust, and had been tested in the worst reentry scenarios back in 1973-74.

Ralf Blueford floated through the cargo block. Its destination was a control station located at the rear. From there, he would visually monitor docking to Liberty. He would obviously be in radio contact with Mattingly and the ground during the manoeuvre. He entered the small cabin and carefully strapped itself to the seat. “”Hello Tom !” he contacted Mattingly “Look at me, the space crane operator.” Now let’s dock this thing for real he muttered for himself.

Unlike Apollo, Helios docked backward. Control of the spacecraft had been transferred from the reentry module to Ralf Blueford. He was now piloting Helios toward space station Liberty. Step by step, acting on the thrusters and RCS, talking to the station crew and to the ground, he get closer and closer. “Contact !” a small vibration shaked the capsule “Excellent ! Smooth as air”.

…

His crewmates were now shutting systems in the reentry module, transferring power to the cargo block, preparing for transfer to the station. They joined Ralf Blueford near the second hatch, the one giving access to Liberty.

Mattingly and Ride warmly welcomed the crew. They progressed through the station central tunnel, to the crew quarters. There were room aplenty, even more than in Skylab. Coming after Helios cramped quarters, the base block looked immense, smart and comfortable.

The four crew quarters were true little motel room, each with its own bunk, a personal desk and locker facilities. There were hot and cold water, refrigeration and cooking facilities. A hygiene unit enabled the crew to wash and shower. And, above all, were the toilets. Gone were Apollo horrendous waste collection bags that the astronauts had to… glue to their buttocks.

For the first time were five people in Liberty. And the number would grow over the years. The space station had better to be comfortable – yet comfort in space had a tortuous history. Back in the mid-60's Apollo was anything but comfortable; fortunately astronauts spent a maximum of two weeks in space.

Skylab, however promised to be different.

In 1967 manned spaceflight czar George Mueller took a strong interest in the orbital workshop (not Skylab yet !), especially the layout of the living quarters. Looking at the mockup, Mueller was appalled by the barren, mechanical character of the workshop interior. "Nobody could have lived in that thing for more than two months," he said of it later; "they'd have gone stir-crazy." Expressing this concern to Skylab managers Lee Belew and Charles Mathews, he suggested that an industrial design expert be brought in to give the workshop "some reasonable degree of creature comfort.

For the habitability study, Skylab contractor Martin Marietta chose one of the best known industrial design firms in the world-Raymond Loewy/William Snaith, Inc., of New York. Loewy, a pioneer of industrial design in the United States, had worked on functional styling for a variety of industrial products for forty years, besides designing stores, shopping centers, and office buildings.

Approaching his 75th birthday in 1968, Loewy had reduced the scope of his own professional activity somewhat, but he took a personal interest in the workshop project. Loewy produced a formal report in February 1968, citing many faults in the existing layout and suggesting a number of improvements. The interior of the workshop was poorly planned; a working area should be simple, with enclosed and open areas "flow[ing] smoothly as integrated elements . . . against neutral backgrounds." While they found a certain "honesty in the straightforward treatment of interior space," the overall impression was nonetheless forbidding.

The basic cylindrical structure clashed with rectangular elements and with the harsh pattern of triangular gridwork liberally spread throughout the workshop. The visual environment was badly cluttered. Lights were scattered apparently at random over the ceiling, and colors were much too dark. This depressing habitat could, however, be much improved simply by organized use of color and illumination.

Loewy recommended a neutral background of pale yellow, with brighter accents for variety and for identifying crew aids, experiment equipment, and personal kits. Lighting should be localized at work areas, and lights with a warmer spectral range substituted for the cold fluorescents used in the mockup. Loewy recommended creating a wardroom-a space for eating, relaxing, and handling routine office work-and Martin's engineers concurred. Better yet, the floor plan should be made flexible by the use of movable panels, so that different arrangements could be tested. Evaluating a single layout was not a good way to acquire information about the design of space stations.

Mueller was pleased with Loewy's work, and a new contract was drawn up engaging the firm through 1968. By now Houston was taking greater interest in the crew quarters, and the new Loewy/Snaith contract specifically provided that the consultants would work with the principal investigator for Houston's habitability experiment.

By September 1969 George Mueller was concerned that Huntsville was not acting on Loewy's ideas, so he called a meeting on habitability for mid-October. The meeting principals (including Raymond Loewy, who came at Mueller's invitation) met in Washington on 14 October for a general review of the habitability support system. Mueller left the clear impression that he was not satisfied with the handling of crew quarters. During the day all aspects of habitability were discussed, including some that had major impact on the workshop structure. Both Loewy and Johnson had suggested rearranging the floor plan to provide a wardroom; both had also endorsed adding a large window to allow the crew to enjoy the view from orbit, something that had been impossible in the wet workshop. The wardroom was easily agreed to, but the window created an impasse. While everyone agreed that it would be very nice to have, Belew pointed out that a window posed one of the toughest problems a spacecraft designer could face. It was too costly, it would weaken the structure, it would take too long to develop and test, and it was not essential to mission success. Counterarguments could not rebut his position.

Finally, Mueller asked Loewy for an opinion. The response was unequivocal; it was unthinkable, Loewy said, not to have a window. Its recreational value alone would be worth its cost on a long mission. With that, Mueller turned to Belew and said, "Put in the window." Schneider formally authorized the window and the wardroom, along with several other changes.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Iron Curtain, G alina Balashova was at work on Soyuz interior partitions. Balashova was a woman and an architect, working for OKB-1 on the space program. That made her a pretty unique recruit, but Korolev needed his work to make the Soyuz habitable. For the record Apollo was pretty unlivable: it famously lacked something as basic as a toilet, with astronauts shitting in plastic bags glued to their ass, a system so horrible that the Apollo 12 crew prefered eating a boatload of immodium rather than using it. By contrast the smaller Soyuz was far more liveable. Korolev had added a living quarter atop the reentry capsule, and Balashkova had been tasked to make it pleasant to live, tackling things like spatial proportions, the psychological effects of colors or the functional distribution of technical equipment.

In the mid-70's the architects were once again called to the rescue for both Liberty and MKBS-1 large space stations. Raymond Loewy was definitively too old, but he passed the torch to an extremely gifted young artist, John Frassanito.

On the soviet side, Balashova was tasked to make the future MKBS-1 an habitable place. With the core module 22 ft in diameter, Balashova main issue was to make that enormous volume an habitable place. Unbestknown to her Frassanito was facing similar issues with the american space station; the core module was even wider than either MKBS-1 or Skylab, a good 33 ft in diameter.

While Frassanito had switched to computer design at the Datapoint company, he agreed to work part-time for NASA on Liberty interior design (which included some Datapoint computers, by the way).

Frassanito sought to apply Loewy Skylab lessons to Liberty

• Each astronaut should be allowed eight hours of solitude daily. (this concept led to the first private rooms in a spacecraft)

• Astronauts would be secured for meals facing each other, in a triangular layout. There were three crew members, and Loewy's layout prevented any hierarchal table-seating issues that could cause tension.

• Partitions would be smooth and flush to facilitate cleanup after the inevitable bouts of space sickness.

Where every other space station module ever built is laid out internally like, say, a trailer, longways, with a floor and a ceiling running longways down the pressurized cylinder, Skylab was arranged more like a skyscraper, a pattern Liberty followed and improved. That means vertically, with actual "decks" or floors of open metal framework set into it. There were two main habitable floors, with an additional module for the solar telescope array. The "upper" main module floor had so much room that it was used for indoor testing of a prototype NASA spacewalking mobility backpack.

Balashova once painted murals for the interior of the Soyuz habitation module. She chose a winter landscape from her home city of Lobyna, the view from her apartment, and the summertime beach in the Black Sea city of Sudak, among other scenes. She did the same for the MKBS-1 interior, albeit on a very different scale. Notably, Balashova integrated a lack of gravity into her design, choosing dark colors for the floor and bright colors for the ceiling. There was an important psychological effect to this, given that astronauts, so accustomed to life on Earth, would be less likely to get disoriented inside the Soyuz's habitation module. Balashova was also responsible for lighting and furnishing design, including living areas, a cabinet equipped with a bookshelf and a folding table, all with a range of colors intended to improve human orientation in zero gravity.

...

April 12, 1980

Ken Mattingly and Sally Ride returned to Earth. Crew awoke to Chicago If you me leave now.

They carefully closed the controversial access hatch through their heatshield and undocked. Later they jettisoned the large logistic module and the adapter. Their capsule reentered ass-first, ablating the heatshield. Still high in the atmosphere, a small chute sprouted of the nose, turning the capsule into a nose-first attitude, ready for the next step: the parafoil deployment.

Unlike Apollo they had an horizontal ranging capability instead of simply following the wind as in a conventional parachute. They we are able to maneuver even into the wind through developing an airplane-like lift on their canopy. It enabled Helios to maneuver even in the presence of high -winds to a preselected point for landing.

Mattignly changed the relative attitude of the spacecraft and the parachute through a system of line pulls. Using this mechanism he could roll the spacecraft, or move it on ahead or bring it in short.

They had control capability for about 20 to 30 miles of range with the lifting canopy alone. Together with the offset center of gravity in reentry Big Gemini could maneuver an extra hundred miles for a grand total in the neighborhood of a hundred and twenty miles - not bad, but a mere 5 percent of the lost space shuttle 1500 miles crossrange. The Big G parawing was sensitive to bad weather, and strategies had had to be invented to bring the spaceship down to Earth in a reasonable time even with uncooperative weather.

The operational approach with a system like this was just what NASA did on Apollo 9 — the crew would wait to deorbit, going another orbit around and changing their reentry point. As such NASA had selected a network of alternate landing sites.

Low inclinations flights had a row of very good landing sites across the Southern United States which gave crews the ability to land several places between the west coast and the east coast. Four sites were prime recovery sites. With an adequate number of passes weather was never a true issue - that, and Big G reentry module was small, light and seldom reused, so bringing back to the Cape was hardly an expensive priority. It was fortunate, because the module width of 14 feet mandated a Supper Guppy or a C-133 large-diameter cargo aircraft... or a Sikorsky CH-54 Skycrane helicopter !

As for higher inclinations orbits -recovery sites used locations in the whole United States. The parawing developped a lifting force that allowed landings with a good enough precision — although not at a place like Los Angeles International Airport, but certainly at places like Palmdale, Edwards, White Sands, or Green River.

They were now floating a mile above Florida, on clear skies with very little winds and a superb view of the space coast. There, NASA and the Air Force shared a narrow penninsula. They flew over the deserted Merrit Island Launch Complex 39 gantries, over the big cube that was the Vehicle Assembly Building. But they would not land there; north of the VAB stood an empty, rough patch of land that had never been turned into a space shuttle landing strip.

Mattingly instead guided the capsule to the military area, to Cape Canaveral Air Force station. After a gentle touchdown, Big Gemini wheeled down to a perfect stop on the military airfield, the so-called skid strip.

(Yes, I wanted wheels, not skids, on Big Gemini, cute little wheels)

Last edited: