You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Earlier Permanent Settlement of New France

- Thread starter Viriato

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

French and British in India

India had ranked a distant third in priorities for both the British and French during the last war, as it was seen mostly as a commercial enterprise. Both French India and British India was governed by the Compagnie des Indes Orientales and the British East India Company respectively.

The first fighting between the two countries on the subcontinent only occurred during the War of Austrian Succession when France took Britain's fort at Madras. This was later returned in exchange for St. Lucia in the Caribbean.

However, French Governor-General Joseph Dupleix (1742-1754) had imagined the French ruling India. To that end he sought alliances with various Indian princes and a proxy war between French-backed and British-backed princes developed in the 1750s. The main French allies were the Kingdom of Mysore in the South and Hyderabad (which was in theory at least, a province of the Mughal Empire).

The British East India Company was largely independent of the British Government, and simply relied on parliament for a renewal of its royal charter. In contrast, the French Compagnie des Indes was largely a tool of Versailles and dependent on the French crown for troops and naval support. Also, the British company, had its control divided into three separate councils (Madras, Calcutta, and Bombay), meanwhile the French company was centralized in Pondicherry under the rule of a Governor-General. The result was that though French India was stronger militarily, however, by 1750, the British company generated four times as much trade as its French counterpart.

During the 1756-1758 war between Britain and France, the French had much larger naval forces in the Indian Ocean and were able to establish definitive control over the Northern Circars region. However, in 1756 the British were able to seize the French outpost of Chandernagore in Bengal and definitively establish their control over Bengal under Robert Clive. At the end of the war Chandernagore was returned to the French with the provision that they were not allowed to fortify it. A siege of British Madras was also lifted in June 1758 once news arrived in India of peace between Britain and France.

During the years following the war, the French would encourage the King of Mysore to overrun the smaller states of Coorg and Bednor, thereby expanding French invluence. Along with the Nizam of Hyderabad, the King of Mysore would become a vassal of the King of France once the French crown assumed direct control over French India from the Compagnie des Indes Orientales in 1769, due to its financial insolvency.

The war had accumulated the debts for the British East India Company as well. The company had to lower its dividends (although it was still able to pay them unlike its French counterpart). Also needing to be addressed, was the company being governed by three separate councils in India and lacking a unified command structure. Through the Regulating Act (1773), the British government, sought to unify British India by appointing a Governor-General in Calcutta to rule over all of British India. This would be followed by the 1784 India Act, granting the British government a larger role in the company's governance.

India had ranked a distant third in priorities for both the British and French during the last war, as it was seen mostly as a commercial enterprise. Both French India and British India was governed by the Compagnie des Indes Orientales and the British East India Company respectively.

The first fighting between the two countries on the subcontinent only occurred during the War of Austrian Succession when France took Britain's fort at Madras. This was later returned in exchange for St. Lucia in the Caribbean.

However, French Governor-General Joseph Dupleix (1742-1754) had imagined the French ruling India. To that end he sought alliances with various Indian princes and a proxy war between French-backed and British-backed princes developed in the 1750s. The main French allies were the Kingdom of Mysore in the South and Hyderabad (which was in theory at least, a province of the Mughal Empire).

The British East India Company was largely independent of the British Government, and simply relied on parliament for a renewal of its royal charter. In contrast, the French Compagnie des Indes was largely a tool of Versailles and dependent on the French crown for troops and naval support. Also, the British company, had its control divided into three separate councils (Madras, Calcutta, and Bombay), meanwhile the French company was centralized in Pondicherry under the rule of a Governor-General. The result was that though French India was stronger militarily, however, by 1750, the British company generated four times as much trade as its French counterpart.

During the 1756-1758 war between Britain and France, the French had much larger naval forces in the Indian Ocean and were able to establish definitive control over the Northern Circars region. However, in 1756 the British were able to seize the French outpost of Chandernagore in Bengal and definitively establish their control over Bengal under Robert Clive. At the end of the war Chandernagore was returned to the French with the provision that they were not allowed to fortify it. A siege of British Madras was also lifted in June 1758 once news arrived in India of peace between Britain and France.

During the years following the war, the French would encourage the King of Mysore to overrun the smaller states of Coorg and Bednor, thereby expanding French invluence. Along with the Nizam of Hyderabad, the King of Mysore would become a vassal of the King of France once the French crown assumed direct control over French India from the Compagnie des Indes Orientales in 1769, due to its financial insolvency.

The war had accumulated the debts for the British East India Company as well. The company had to lower its dividends (although it was still able to pay them unlike its French counterpart). Also needing to be addressed, was the company being governed by three separate councils in India and lacking a unified command structure. Through the Regulating Act (1773), the British government, sought to unify British India by appointing a Governor-General in Calcutta to rule over all of British India. This would be followed by the 1784 India Act, granting the British government a larger role in the company's governance.

Portuguese and Dutch India

The Portuguese Empire in India had been largely moribund since their defeat by the Marathas in 1737-1740, forcing the Portuguese to cede Bassein, Chaul, Sirgão, Quelme, Ilha das Vacas (Arnala), Caranja (Karanja) to the Marathas (today suburbs of Mumbai).

However, having remained neutral during the Seven Years War, the Portuguese had been able to build up a formidable navy of 24 ships of the line and add a military presence of 3,000 soldiers to Goa. Though nowhere near its 16th and 17th centuries peak of power, it was a renaissance of sorts under Portugal's prime minister the Marquis de Pombal

Also, the Portuguese quickly began to appreciate the revenue from collecting taxes over villages rather than simply relying on trade. To that end, the Portuguese engaged in a war with the Raja of Soonda (Sodhe) in 1752 finally building a fort at south of Goa Batcal (Bhatkal). In 1764, after the capture of Bendor by Mysore, the Raja of Soonda fled to Goa and ceded his territories to the Portuguese. Ironically the Portuguese began cooperating with their former foes the Dutch to the south. Thus the Portuguese were able to add territory far south of Goa. This culminated in the reconquest of Mangalore with its significant Catholic population.

The French who had been hoping to get Portugal to be an ally while wanting to keep the British from the area, brokered an agreement between the Portuguese and Mysore. Portugal was able annex the province of Sira due to infighting by 1766, including Carwar (Karwar) and Sadhishgivad. Further to the North, the Portuguese made peace with the Marathas and in 1779 they were allowed to collect revenues at over 100 villages outside of Damão, allowing Portugal to effectively annex Dadra and Nagar Haveli. Finally between 1765 and 1788 they annexed the lands north of Goa.

To the south, the Dutch had suffered a setback during the Travancore-Dutch War ending in 1753. However, with the upheaval in India the Dutch would take advantage of gaining control over much of the Malabar, the Cochin Sultanate and Travancore by 1760. Here too the French preferred Dutch control as a formula to thwart the British from gaining a foothold in the region. In Bengal, the Dutch were less successful, only retaining a factory at Hooghly.

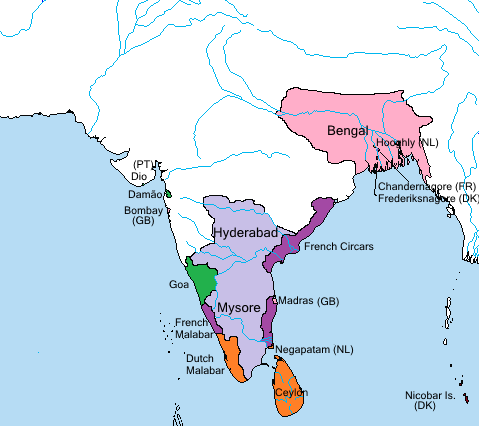

Map of ares of India under European Rule 1780

The Portuguese Empire in India had been largely moribund since their defeat by the Marathas in 1737-1740, forcing the Portuguese to cede Bassein, Chaul, Sirgão, Quelme, Ilha das Vacas (Arnala), Caranja (Karanja) to the Marathas (today suburbs of Mumbai).

However, having remained neutral during the Seven Years War, the Portuguese had been able to build up a formidable navy of 24 ships of the line and add a military presence of 3,000 soldiers to Goa. Though nowhere near its 16th and 17th centuries peak of power, it was a renaissance of sorts under Portugal's prime minister the Marquis de Pombal

Also, the Portuguese quickly began to appreciate the revenue from collecting taxes over villages rather than simply relying on trade. To that end, the Portuguese engaged in a war with the Raja of Soonda (Sodhe) in 1752 finally building a fort at south of Goa Batcal (Bhatkal). In 1764, after the capture of Bendor by Mysore, the Raja of Soonda fled to Goa and ceded his territories to the Portuguese. Ironically the Portuguese began cooperating with their former foes the Dutch to the south. Thus the Portuguese were able to add territory far south of Goa. This culminated in the reconquest of Mangalore with its significant Catholic population.

The French who had been hoping to get Portugal to be an ally while wanting to keep the British from the area, brokered an agreement between the Portuguese and Mysore. Portugal was able annex the province of Sira due to infighting by 1766, including Carwar (Karwar) and Sadhishgivad. Further to the North, the Portuguese made peace with the Marathas and in 1779 they were allowed to collect revenues at over 100 villages outside of Damão, allowing Portugal to effectively annex Dadra and Nagar Haveli. Finally between 1765 and 1788 they annexed the lands north of Goa.

To the south, the Dutch had suffered a setback during the Travancore-Dutch War ending in 1753. However, with the upheaval in India the Dutch would take advantage of gaining control over much of the Malabar, the Cochin Sultanate and Travancore by 1760. Here too the French preferred Dutch control as a formula to thwart the British from gaining a foothold in the region. In Bengal, the Dutch were less successful, only retaining a factory at Hooghly.

Map of ares of India under European Rule 1780

Spain's Enlightenment

During much of the 18th century, Spain would undergo a period of resurgence bringing the Spanish monarchy a period of prosperity and prestige not seen since the reign of Philip II. Spain fared well under the enlightened monarchs of Ferdinand VI and his half-brother Charles III. Though the enlightenment did spread to Spain, the religiosity of its people made it a different sort of enlightenment that was at the time derided by the likes of Voltaire and man English contemporaries.

One of the most progressive reforms instituted in Spain and its colonies in 1748-1749 was tax reform where land was taxed according to the size of holdings. After the War of Jenkins' Ear with Britain, the Spanish crown sought to raise funds to pay off the public debt. This included setting up a royal lottery along with the Bank of San Carlos to sell bonds for the state.

One of the most far-reaching reforms was allocating underutilized municipal to the poor in Spain and in its colonies. Though many of the land reforms were opposed by the large land-owning class, they helped bring popularity to the Spanish monarchy among the majority of people. Finally, the establishment of "pósitos", seed banks for the poor to obtain seeds for planting crops when they did not have any.

To carry on more reforms, in 1766, Carlos III appointed the Count of Aranda, who was a Freemason as his prime minister. Aranda strongly believed that the prosperity of Spain depended on the well being of its small farmers and peasants. To that end, more municipal lands were given to the poor and many more were given lands in the Americas to colonize (mostly in New Spain and La Plata). He also reorganized the police, and abolished many capital crimes. Finally, Aranda had roads repaired and new ones built along with sanitation services implemented in Spanish cities to greatly improve public health.

Also important during this period were the military reforms. After the short war with Britain culminating in the retaking of Gibraltar and Minorca, Carlos III set about on an ambitious naval building programme to increase the Spanish navy's strength to 300 vessels with 130,000 men. By 1770, the Spanish naval power approached that of Britain and France with 70 modern ships of the line, including 12 94-gun ships and another 16 112 gun ships built between 1779 and 1790.

Finally, the Catholic church was subjected to more royal authority, this culminated wit the Jesuits were expelled from Spain and its colonies in 1767 (being replaced by the Franciscans in the Spanish colonies).

During much of the 18th century, Spain would undergo a period of resurgence bringing the Spanish monarchy a period of prosperity and prestige not seen since the reign of Philip II. Spain fared well under the enlightened monarchs of Ferdinand VI and his half-brother Charles III. Though the enlightenment did spread to Spain, the religiosity of its people made it a different sort of enlightenment that was at the time derided by the likes of Voltaire and man English contemporaries.

One of the most progressive reforms instituted in Spain and its colonies in 1748-1749 was tax reform where land was taxed according to the size of holdings. After the War of Jenkins' Ear with Britain, the Spanish crown sought to raise funds to pay off the public debt. This included setting up a royal lottery along with the Bank of San Carlos to sell bonds for the state.

One of the most far-reaching reforms was allocating underutilized municipal to the poor in Spain and in its colonies. Though many of the land reforms were opposed by the large land-owning class, they helped bring popularity to the Spanish monarchy among the majority of people. Finally, the establishment of "pósitos", seed banks for the poor to obtain seeds for planting crops when they did not have any.

To carry on more reforms, in 1766, Carlos III appointed the Count of Aranda, who was a Freemason as his prime minister. Aranda strongly believed that the prosperity of Spain depended on the well being of its small farmers and peasants. To that end, more municipal lands were given to the poor and many more were given lands in the Americas to colonize (mostly in New Spain and La Plata). He also reorganized the police, and abolished many capital crimes. Finally, Aranda had roads repaired and new ones built along with sanitation services implemented in Spanish cities to greatly improve public health.

Also important during this period were the military reforms. After the short war with Britain culminating in the retaking of Gibraltar and Minorca, Carlos III set about on an ambitious naval building programme to increase the Spanish navy's strength to 300 vessels with 130,000 men. By 1770, the Spanish naval power approached that of Britain and France with 70 modern ships of the line, including 12 94-gun ships and another 16 112 gun ships built between 1779 and 1790.

Finally, the Catholic church was subjected to more royal authority, this culminated wit the Jesuits were expelled from Spain and its colonies in 1767 (being replaced by the Franciscans in the Spanish colonies).

Spanish America

Spanish Prime Minister the Count of Aranda had predicted at the rate New France was growing "it will aspire to the conquest of New Spain". To that end settling the borderlands of New Spain became a priority, especially after peace was established in 1758.

By the mid-18th century Spain once again had a growing population and it was decided to exploit this for the benefit of the Spanish New World. Before the 18th century, Spanish migrants to the New World were overwhelmingly males and mostly came from Andalusia, Extremadura and to a lesser extent Madrid. However, in the 18th century the Spanish crown began to settle entire families from the Canary Islanders in Cuba, Puerto Rico, Santo Domingo and in Venezuela. In Texas, they were settled in large numbers as well.

During Carlos III's reign Galician families were recruited to Texas, and after beginning in 1770 to Alta California. There they would launch a successful dairy industry. Basques too began arriving in large numbers around the same time with some 12,000 arriving in West Texas between 1765 and 1800, with another 4,000 settling in New Mexico. Many of the basques became shepherds and would establish a successful wool industry in the driest areas of the borderlands of New Spain. Finally, the establishment of vineyards by Franciscan monks was followed by the introduction of large numbers of people from Aragon.

One of the most enterprising colonial governors during this period was the Count of Gálvez who served as Governor of Texas from 1777-1785 and Viceroy of New Spain 1785-1786. In Texas, he established Puerto Gálvez (Galveston) in 1780 and introduced large numbers of Basque and Canarian colonists to the region, helping to thwart French expansion westward.

Below are the figures of the Spanish population in the respective borderlands of New Spain in 1800

Alta California 75,000

New Mexico 28,000

Texas 205,000

Further south, in La Plata, the Spanish were threatened by the increasing Portuguese expansion of Brazil. The Portuguese had long been settling west of the line set by Treaty of Tordesillas and the ever increasing number of Portuguese settlers arriving, especially in the south threatened Spanish rule over Rio de la Plata. Between 1700 and 1760, 600,000 Portuguese settled in Brazil, double the number of Spaniards settling in Spanish America during the same period, and many of them were settling further south. The border dispute with the Portuguese had led to a brief war between the two countries in 1776-1777 where the Spanish captured the Portuguese settlement of Colonia do Sacramento (Uruguay).

With the British failing to help the Portuguese in this dispute and the death of King José I of Portugal, Queen Maria I began to seek an alliance with Spain and France. To that end, France helped mediate the dispute and the Treaty of San Ildefonso was the result in 1777. Spain would finally recognize Portugal's conquests into the interior of South America as fait accompli.

Spanish Prime Minister the Count of Aranda had predicted at the rate New France was growing "it will aspire to the conquest of New Spain". To that end settling the borderlands of New Spain became a priority, especially after peace was established in 1758.

By the mid-18th century Spain once again had a growing population and it was decided to exploit this for the benefit of the Spanish New World. Before the 18th century, Spanish migrants to the New World were overwhelmingly males and mostly came from Andalusia, Extremadura and to a lesser extent Madrid. However, in the 18th century the Spanish crown began to settle entire families from the Canary Islanders in Cuba, Puerto Rico, Santo Domingo and in Venezuela. In Texas, they were settled in large numbers as well.

During Carlos III's reign Galician families were recruited to Texas, and after beginning in 1770 to Alta California. There they would launch a successful dairy industry. Basques too began arriving in large numbers around the same time with some 12,000 arriving in West Texas between 1765 and 1800, with another 4,000 settling in New Mexico. Many of the basques became shepherds and would establish a successful wool industry in the driest areas of the borderlands of New Spain. Finally, the establishment of vineyards by Franciscan monks was followed by the introduction of large numbers of people from Aragon.

One of the most enterprising colonial governors during this period was the Count of Gálvez who served as Governor of Texas from 1777-1785 and Viceroy of New Spain 1785-1786. In Texas, he established Puerto Gálvez (Galveston) in 1780 and introduced large numbers of Basque and Canarian colonists to the region, helping to thwart French expansion westward.

Below are the figures of the Spanish population in the respective borderlands of New Spain in 1800

Alta California 75,000

New Mexico 28,000

Texas 205,000

Further south, in La Plata, the Spanish were threatened by the increasing Portuguese expansion of Brazil. The Portuguese had long been settling west of the line set by Treaty of Tordesillas and the ever increasing number of Portuguese settlers arriving, especially in the south threatened Spanish rule over Rio de la Plata. Between 1700 and 1760, 600,000 Portuguese settled in Brazil, double the number of Spaniards settling in Spanish America during the same period, and many of them were settling further south. The border dispute with the Portuguese had led to a brief war between the two countries in 1776-1777 where the Spanish captured the Portuguese settlement of Colonia do Sacramento (Uruguay).

With the British failing to help the Portuguese in this dispute and the death of King José I of Portugal, Queen Maria I began to seek an alliance with Spain and France. To that end, France helped mediate the dispute and the Treaty of San Ildefonso was the result in 1777. Spain would finally recognize Portugal's conquests into the interior of South America as fait accompli.

Spanish Moroccan War 1774-1775

In the Mediterranean, the pirates of the Barbary Coast had long plagued the coastal settlements of Southern Europe, sacking coastal cities and kidnapping Christians to enslave or ransom them back to European powers. Algiers, Tripoli and Tunis were the principal ports out of which the corsairs operated, however they were based in Morocco as well. Piracy for the Beys of Algiers and Tunis had become their major source of revenue. The principal victims of these attacks were southern Spain, Portugal, Italy and especially the Balearic Islands, Corsica, Sardinia and Sicily. However, in the 17th century the corsairs had managed to launch a raid as far north as the Irish coast.

Spain for its part had used Muslim captives as galley slaves, just as the Barbary pirates had with Christian slaves. However, by the mid-18th century galleys were a thing of the past, and galley slaves were obsolete. Therefore, beginning in 1739 the Spaniards began exchanging their Muslim captives for Christian captives. Though this proved popular with the populace of Algiers and Tunis, it brought no revenue to the rulers of these states. They became wary of giving up Christians without any monetary compensation. Therefore, the last exchange of prisoners was in 1768 and 1769. The Bey of Algiers especially sought revenue in this fashion and demanded that ransoms be paid for all Christian prisoners. Beginning in 1760, the raids on European shipping increased greatly. In Corsica, these were so detrimental, that the Genoese government sold the island to the French in 1768.

With the increase of pirate activity in the western Mediterranean, several of the powers launched punitive expeditions against the Algiers, Tunis and Morocco, including the bombardment of Salé and Larache in Morocco by the French in 1765. After that point, Morocco was arguably the weakest of the Barbary States, having a corsair fleet of barely 20 ships. Therefore, to increase his revenue, Sultan Mohammed III laid siege to the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla In December 1774. With some 40,000 troops, including a large number of mercenaries from Algiers, the siege was particularly daunting for the Spaniards of Melilla. However, the Irish-born governor of Melilla Juan Sherlocke defended the city until a relief fleet arrived in March 1775.

Under the command of another Irishman, Alejandro (Alexander) O’Reilly, a Spanish Army of 45,000 men loaded with heavy artillery landed west of Melilla and relieved the city of its siege in March 1775. Afterwards, capturing Nador and encircling Mount Gourougou. Meanwhile, a large Spanish fleet began bombarding Tangier and later Larache and Salé. The Spanish expeditionary force sailed to Ceuta and captured Tangier, Tetuán, Arcila (Asilah), Larache, while a smaller force captured Salé. Most of the Algerian mercenaries fled back to Algiers and the Sultan sued for peace. As the Spanish forces with superior artillery approached the cities, the inhabitants fled en masse, leaving empty cities for the Spanish to take.

As a result of the peace treaty in 1780, the Spanish annexed all of the cities they had captured and much of the surrounding lands. They began fortifying Tangier, Salé and Larache to prevent future use by any corsairs, and began the colonization of their new settlements. In Spain, the war brought a surge of popularity and it was heralded as the new Reconquista. It was also seen a reversal of fortunes as the Larache was once again Spanish, after having lost it to the Moroccan forces in 1689. Now that Spain had annexed a large part of the surrounding countryside around its fortresses, it recruited colonists from Andalusia to the new Spanish settlements. Many were tempted by the offers of free homes and land. However, the Moroccans would continue to harass the borders for years to come, which would eventually lead to another war.

Alejandro O'Reilly, Conde de O'Reilly

In the Mediterranean, the pirates of the Barbary Coast had long plagued the coastal settlements of Southern Europe, sacking coastal cities and kidnapping Christians to enslave or ransom them back to European powers. Algiers, Tripoli and Tunis were the principal ports out of which the corsairs operated, however they were based in Morocco as well. Piracy for the Beys of Algiers and Tunis had become their major source of revenue. The principal victims of these attacks were southern Spain, Portugal, Italy and especially the Balearic Islands, Corsica, Sardinia and Sicily. However, in the 17th century the corsairs had managed to launch a raid as far north as the Irish coast.

Spain for its part had used Muslim captives as galley slaves, just as the Barbary pirates had with Christian slaves. However, by the mid-18th century galleys were a thing of the past, and galley slaves were obsolete. Therefore, beginning in 1739 the Spaniards began exchanging their Muslim captives for Christian captives. Though this proved popular with the populace of Algiers and Tunis, it brought no revenue to the rulers of these states. They became wary of giving up Christians without any monetary compensation. Therefore, the last exchange of prisoners was in 1768 and 1769. The Bey of Algiers especially sought revenue in this fashion and demanded that ransoms be paid for all Christian prisoners. Beginning in 1760, the raids on European shipping increased greatly. In Corsica, these were so detrimental, that the Genoese government sold the island to the French in 1768.

With the increase of pirate activity in the western Mediterranean, several of the powers launched punitive expeditions against the Algiers, Tunis and Morocco, including the bombardment of Salé and Larache in Morocco by the French in 1765. After that point, Morocco was arguably the weakest of the Barbary States, having a corsair fleet of barely 20 ships. Therefore, to increase his revenue, Sultan Mohammed III laid siege to the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla In December 1774. With some 40,000 troops, including a large number of mercenaries from Algiers, the siege was particularly daunting for the Spaniards of Melilla. However, the Irish-born governor of Melilla Juan Sherlocke defended the city until a relief fleet arrived in March 1775.

Under the command of another Irishman, Alejandro (Alexander) O’Reilly, a Spanish Army of 45,000 men loaded with heavy artillery landed west of Melilla and relieved the city of its siege in March 1775. Afterwards, capturing Nador and encircling Mount Gourougou. Meanwhile, a large Spanish fleet began bombarding Tangier and later Larache and Salé. The Spanish expeditionary force sailed to Ceuta and captured Tangier, Tetuán, Arcila (Asilah), Larache, while a smaller force captured Salé. Most of the Algerian mercenaries fled back to Algiers and the Sultan sued for peace. As the Spanish forces with superior artillery approached the cities, the inhabitants fled en masse, leaving empty cities for the Spanish to take.

As a result of the peace treaty in 1780, the Spanish annexed all of the cities they had captured and much of the surrounding lands. They began fortifying Tangier, Salé and Larache to prevent future use by any corsairs, and began the colonization of their new settlements. In Spain, the war brought a surge of popularity and it was heralded as the new Reconquista. It was also seen a reversal of fortunes as the Larache was once again Spanish, after having lost it to the Moroccan forces in 1689. Now that Spain had annexed a large part of the surrounding countryside around its fortresses, it recruited colonists from Andalusia to the new Spanish settlements. Many were tempted by the offers of free homes and land. However, the Moroccans would continue to harass the borders for years to come, which would eventually lead to another war.

Alejandro O'Reilly, Conde de O'Reilly

Spanish Algeria

Once news reached Europe and America of the Spanish victory over the “Moors” there was jubilation not only in Spain’s empire, but in New France as well. The Moroccan war had not yet ended, and King Carlos III began to prepare for an expedition to take an even greater prize, Algiers. Leaving behind a garrison of 11,000 men in the Moroccan conquests, the Spanish prepared a formidable invasion force to take Algiers and strike at the very epicenter of the Barbary Coast.

In the spring of 1775, an invasion force was assembled in Alicante under General Alejandro O’Reilly. The immense Spanish force consisted of 51 Ships of the Line and Frigates, along with several dozen transport ships and 46,000 men. On night of 10 June 1775, the attack of Algiers commenced. While the troops disembarked with heavy artillery west of Algiers, the Spanish ships began to heavily bombard the fortress of Algiers. They also setup batteries in the harbour, sending more than 12,000 shells against Algiers. Finally on 21 June the walls were breached and the Spaniards took the city. It was in countryside surrounding the city that they met the fiercest resistance, however. This led to bloody reprisals on the part of the Spaniards, who believed they were modern-day crusaders.

Further east in Oran, the Spaniards assembled 11,000 men to hold Oran, until Algiers had fallen. Beginning in August, the Spanish navy began to bombard the ports of Mostaganem and Arsenaria (Arzew) relentlessly. By September, these two cities had fallen to the Spaniards as well as well. Alejandro O’Reilly’s troops swept the countryside, plundering the areas around Oran and Algiers. The Bey fled with the remnants of his men inland Algiers eastward towards Constantine. However, the Arabs would flee to the mountains and continue to harass Spanish settlements for the next 30 years. Meanwhile, others whose lives depended on the sea fled to Tunis and Tripoli.

However the attack on Algeria, this was not solely a Spanish enterprise. Buoyed by the Spanish successes, the Italian states joined what was now being called the “Reconquista”. While the Spaniards attacked Algiers, a force led by the Naples & Sicily was assembled further east outside of La Cala (El Kala and Bona (Annaba). King Carlos III’s son, King Ferdinand of Naples and Sicily entered the war against the Barbary Pirates, because his kingdom had long been a victim of the North African corsairs. Therefore the Neopolitans were to be the spearhead of a multi-national force of 18 warships and 18,000 men to take attack the smaller ports in eastern Algeria. Joining them would be the forces of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, the Papal States and the Knights of Malta. Also, a small Spanish force of 2,000 troops assisted along with several Spanish ships. With little resistance, these towns fell to the Neopolitans and were incorporated into the Kingdom of Sicily and subsequently colonized by Sicilians. However, the remnant of the Bey’s forces based in Constantine would eventually have to be crushed as well.

After his victory, the Count of O’Reilly was appointed Governor of Spanish North Africa. He would spend the next 20 years conquering Algeria west of Bejaia (Bugia) for Spain. The Kingdom of Sicily and Naples was given the country to the east of Bugia. However, it would not be until 1785 when Constantine was finally conquered, though pockets of resistance against Spanish and Italian rule would continue in the Atlas Mountains until 1820.

Once news reached Europe and America of the Spanish victory over the “Moors” there was jubilation not only in Spain’s empire, but in New France as well. The Moroccan war had not yet ended, and King Carlos III began to prepare for an expedition to take an even greater prize, Algiers. Leaving behind a garrison of 11,000 men in the Moroccan conquests, the Spanish prepared a formidable invasion force to take Algiers and strike at the very epicenter of the Barbary Coast.

In the spring of 1775, an invasion force was assembled in Alicante under General Alejandro O’Reilly. The immense Spanish force consisted of 51 Ships of the Line and Frigates, along with several dozen transport ships and 46,000 men. On night of 10 June 1775, the attack of Algiers commenced. While the troops disembarked with heavy artillery west of Algiers, the Spanish ships began to heavily bombard the fortress of Algiers. They also setup batteries in the harbour, sending more than 12,000 shells against Algiers. Finally on 21 June the walls were breached and the Spaniards took the city. It was in countryside surrounding the city that they met the fiercest resistance, however. This led to bloody reprisals on the part of the Spaniards, who believed they were modern-day crusaders.

Further east in Oran, the Spaniards assembled 11,000 men to hold Oran, until Algiers had fallen. Beginning in August, the Spanish navy began to bombard the ports of Mostaganem and Arsenaria (Arzew) relentlessly. By September, these two cities had fallen to the Spaniards as well as well. Alejandro O’Reilly’s troops swept the countryside, plundering the areas around Oran and Algiers. The Bey fled with the remnants of his men inland Algiers eastward towards Constantine. However, the Arabs would flee to the mountains and continue to harass Spanish settlements for the next 30 years. Meanwhile, others whose lives depended on the sea fled to Tunis and Tripoli.

However the attack on Algeria, this was not solely a Spanish enterprise. Buoyed by the Spanish successes, the Italian states joined what was now being called the “Reconquista”. While the Spaniards attacked Algiers, a force led by the Naples & Sicily was assembled further east outside of La Cala (El Kala and Bona (Annaba). King Carlos III’s son, King Ferdinand of Naples and Sicily entered the war against the Barbary Pirates, because his kingdom had long been a victim of the North African corsairs. Therefore the Neopolitans were to be the spearhead of a multi-national force of 18 warships and 18,000 men to take attack the smaller ports in eastern Algeria. Joining them would be the forces of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, the Papal States and the Knights of Malta. Also, a small Spanish force of 2,000 troops assisted along with several Spanish ships. With little resistance, these towns fell to the Neopolitans and were incorporated into the Kingdom of Sicily and subsequently colonized by Sicilians. However, the remnant of the Bey’s forces based in Constantine would eventually have to be crushed as well.

After his victory, the Count of O’Reilly was appointed Governor of Spanish North Africa. He would spend the next 20 years conquering Algeria west of Bejaia (Bugia) for Spain. The Kingdom of Sicily and Naples was given the country to the east of Bugia. However, it would not be until 1785 when Constantine was finally conquered, though pockets of resistance against Spanish and Italian rule would continue in the Atlas Mountains until 1820.

After his victory, the Count of O’Reilly was appointed Governor of Spanish North Africa.

I assume the "of" is a typo, and you know that what you have is impossible?

I assume the "of" is a typo, and you know that what you have is impossible?

In Spanish he was given the title of Conde de O'Reilly which translates to Count of O'Reilly. I go that from "La Nobleza Titulada en la America Española" by Havier Gómez de Olea y Bustinza.

I also looked to "El Ejército Español en el Reinado de Carlos III" and it confirms that was his title.

Hunh. How very odd. Conde O'Reilly would make sense. Conde de 'wherever in Ireland he came from' makes sense. Conde de O'Reilly is crazy. (But it was an OTL crazy mistake, I guess.)In Spanish he was given the title of Conde de O'Reilly which translates to Count of O'Reilly. I go that from "La Nobleza Titulada en la America Española" by Havier Gómez de Olea y Bustinza.

I also looked to "El Ejército Español en el Reinado de Carlos III" and it confirms that was his title.

OTOH, some of the craziest things in TLs turn out to be OTL. Sigh.

Thank you for the response.

Hunh. How very odd. Conde O'Reilly would make sense. Conde de 'wherever in Ireland he came from' makes sense. Conde de O'Reilly is crazy. (But it was an OTL crazy mistake, I guess.)

OTOH, some of the craziest things in TLs turn out to be OTL. Sigh.

Thank you for the response.

For a feat like conquering Algiers, I'm sure we can see him getting a higher title like Duke, so I'm going to change the TL, he is elevated to Duke of Algiers.

War with Turkey 1768-1772

In 1758 the hawkish Duke of Choiseul became Prime Minister of France, virulently anti-British he became obsessed with invading Great Britain. Having missed his opportunity to invade England during the last war, he would spend the next decade and a half searching for a pretense to invade England. He was only restrained by the King, who wished to preserve the peace. However, under his authority French defence costs rose exponentially throughout the 1760s.

Choiseul wanted France to expand as a Mediterranean power, and to that end he had negotiated the acquisition of Corsica from the Republic of Genoa. However, he began to set his sights further east. As early as 1769 Choiseul had begun to look at the moribund Ottoman Empire as a target from which to acquire territory. However, since the reign of Louis XIV, the Porte had been an ally of the French, used as a means of preventing the Hapsburgs from expanding their power. However, the Ottoman Empire had been on the decline throughout the 18th century, and Choiseul thought it more important to repair relations with Austria, which had been damaged by France’s withdrawal from the Seven Years War. However, it would be Russia that would spark the flame of war in the East.

In late 1769, the Russians had marched into Moldavia defeating the Ottomans and by the end of the year they had taken over Wallachia as well. Russian successes mounted, and in 24 June 1770 the Russian fleet defeated an Ottoman fleet twice its size in the Mediterranean. Initially the French sought to support the Ottomans, however their quick victories stunned the French court. The Russians had been backed by the British, as Empress Catherine sought to expand territorially at the expense of both Poland and the Ottoman Empire. Both countries had traditionally been French allies (mostly as a bulwark against the Hapsburgs), however Choiseul began to see both countries as weak, France would need more formidable allies in Europe. Russia’s Empress also began to court an alliance with the French which would give her free reign over both Poland and the Ottoman Empire.

After Russia’s defeat of the Ottoman Navy at the Battle of Chesme, France suddenly began to reevaluate its position vis-à-vis the Ottoman Empire. The Count of Saint-Priest, French ambassador in Constantinople had made a blunt evaluation of the situation, reporting back to Choiseul on the weakness of the Ottoman Army. Also, beginning in 1770, the Russians had begun fomenting a revolt amongst the Greeks of the Ottoman Empire, particularly in Crete and Morea. However, the French did not want the Russians to have a presence in the Mediterranean. Saint-Priest warned that the Ottoman Empire was collapsing and that France should grab the pieces it could before it was too late. The Duc of Choiseul proposed to the king that France enter the war against the Ottomans so as to moderate the Russian gains, meanwhile depriving the British of an ally. Territorial acquisitions also came into play, as France had for a while now displayed ambitions towards annexing Crete.

The revolt amongst the Greeks and their suppression by the Ottomans became the pretext for intervention on behalf of the Christians of the Ottoman Empire. Since the reign of the Louis XIV, the French had appointed themselves as protectors of Christians in the sultan’s domains. In August 1770, a French fleet was assembled in Toulon with a force of 40,000 men to sail for Crete. After landing in Candia, the force faced little resistance and within a two days the Ottoman Pasha surrendered the island to the French. The Pasha departed and with him went several thousand Turks, fearing reprisals from the Greek population. After leaving behind a garrison on Crete of 6,000 men, the bulk of the French forces sailed for Morea, making a landing by September. The French army quickly achieved many victories, having captured Athens by December of 1770. The Russians too had secured the mouth of the Danube by that time.

Several states in Europe became alarmed by this war and what seemed like the end of the Ottoman Empire. The British for their part were shocked by the unforeseen chain of events. The French acquisition of Corsica in 1768 had brought down the government of the Duke of Grafton, and French acquisition of Crete would certainly precipitate another crisis. Though there were many in parliament who pressed for war, the American members of the House of Commons were vehemently against another conflict with France. They remembered the disaster the last war had brought upon the American provinces, along with the taxes they were still paying to reconstruct their defences. Another matter of concern was British dependence on Russia for its naval stores. If Britain were to go to war with Russia, the Royal Navy would be deprived of iron for its cannons, flax for its sailcloth, and most importantly timber for its masts and ships. Despite this, negotiations were underway at the beginning of 1771 with Austria, Sweden and Prussia to form a coalition against France and Russia.

Of all of the great powers, Austria was the most apprehensive about Russia’s gains as Russian troops were had secured Rumelia by the spring of 1771 and heading towards Constantinople. The French troops meanwhile had routed the Ottomans from Macedonia. However, Maria Theresa did not want a war with France. She hoped to strengthen the Franco-Austrian alliance. To that end, the Austrians rebuffed the British and negotiated secretly with the Russians and French for an agreement to acquire territory from the Ottomans as well. Finally, in October 1771, Austrian troops crossed the Danube into Serbia.

Prussia for its part was war-weary and still rebuilding its treasury from the last war. Therefore, the Prussians flatly rejected British attempts to go to war with France. The Prussians were more interested in Poland, and the Austrians along with the Russians seemed to be making progress at partitioning the kingdom. By 1771, the Russians and Austrians had agreed on the details of the partition and Prussia so no need to go to war with either Russia or Austria and risk losing its new acquisitions. The sacrifice of Poland on the part of the French, bought Prussian neutrality in the conflict. On September 1772, the annexation of Polish territory had been ratified by treaty and received the blessing of France. Meanwhile, in Sweden, the death of King Adolf Frederick had led to political turmoil throughout 1771 and 1772, preventing the Swedes from an alliance with Britain.

With the Russians approaching Constantinople, the Ottomans sued for peace in December of 1771. A peace treaty would be formalized in Belgrade in May 1772. The terms of capitulation ended up being much less harsh than expected, largely due to the infighting between Austria and Russia over the spoils of war. Russia had initially hoped for Rumelia, but this was blocked by both France and Austria. Austria for its part had wanted Bosnia too, but was restrained by the French.

In the end, Austria would receive Bukovina, Wallachia and Serbia, with the Austrian rulers now adding the titles of King of Serbia, Prince of Wallachia, and Duke of Bukovina to their already numerous titles. The French would acquire Morea and Crete, with the King of France now assuming the title of the King of Morea and Duke of Candia. Finally, Russia would annex Podolia, Bessarabia and Moldavia, now controlling the mouth of the Dniester. Finally, the Crimean Khanate was recognized as an independent state, however in reality it would be nothing more than a Russian puppet. Karbadia in the Caucasus was also recognized as a vassal of Russia. Other provisions included Russian protection over Orthodox subjects of the Porte, along with access to the Mediterranean.

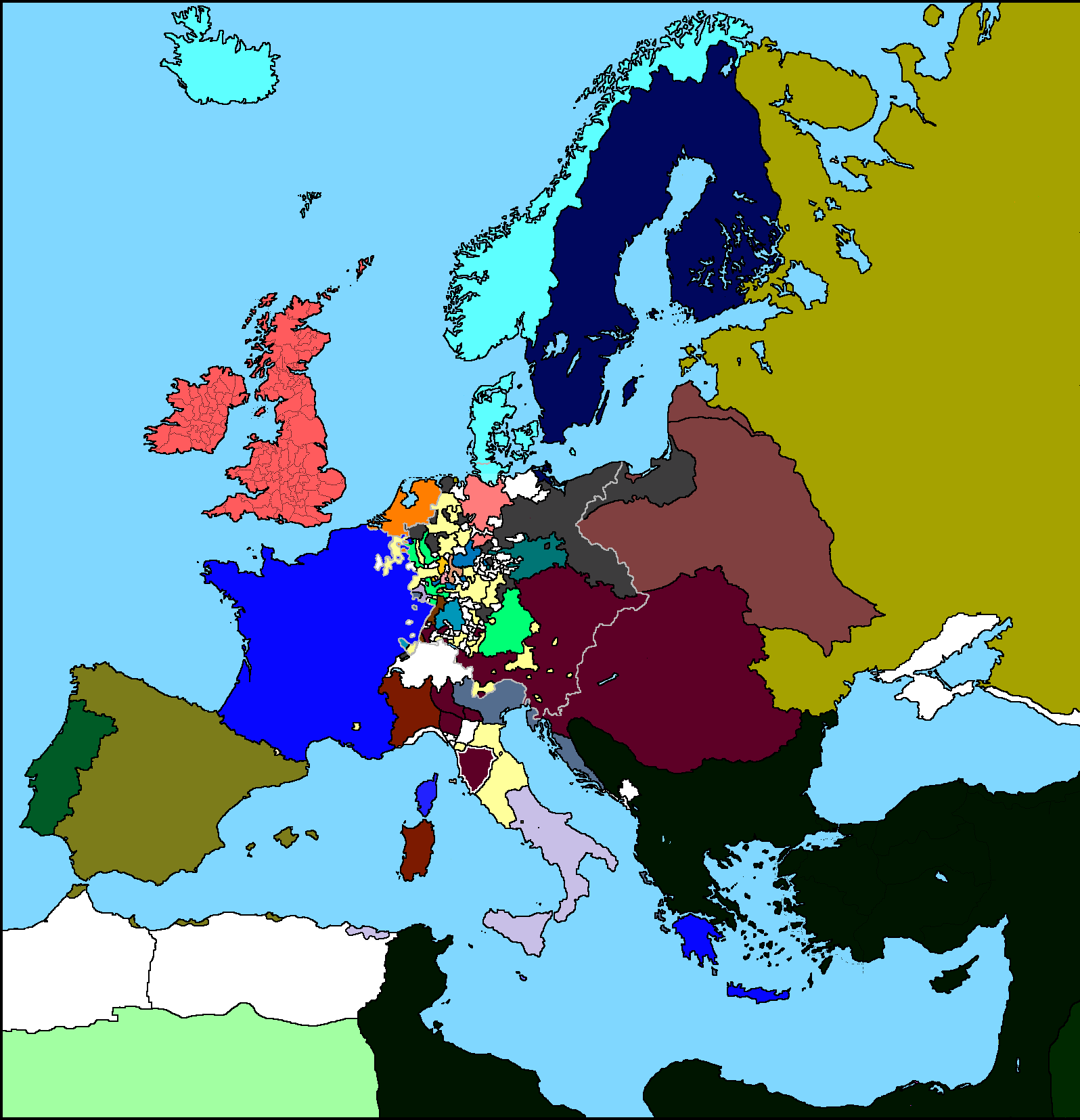

Europe in 1776

In 1758 the hawkish Duke of Choiseul became Prime Minister of France, virulently anti-British he became obsessed with invading Great Britain. Having missed his opportunity to invade England during the last war, he would spend the next decade and a half searching for a pretense to invade England. He was only restrained by the King, who wished to preserve the peace. However, under his authority French defence costs rose exponentially throughout the 1760s.

Choiseul wanted France to expand as a Mediterranean power, and to that end he had negotiated the acquisition of Corsica from the Republic of Genoa. However, he began to set his sights further east. As early as 1769 Choiseul had begun to look at the moribund Ottoman Empire as a target from which to acquire territory. However, since the reign of Louis XIV, the Porte had been an ally of the French, used as a means of preventing the Hapsburgs from expanding their power. However, the Ottoman Empire had been on the decline throughout the 18th century, and Choiseul thought it more important to repair relations with Austria, which had been damaged by France’s withdrawal from the Seven Years War. However, it would be Russia that would spark the flame of war in the East.

In late 1769, the Russians had marched into Moldavia defeating the Ottomans and by the end of the year they had taken over Wallachia as well. Russian successes mounted, and in 24 June 1770 the Russian fleet defeated an Ottoman fleet twice its size in the Mediterranean. Initially the French sought to support the Ottomans, however their quick victories stunned the French court. The Russians had been backed by the British, as Empress Catherine sought to expand territorially at the expense of both Poland and the Ottoman Empire. Both countries had traditionally been French allies (mostly as a bulwark against the Hapsburgs), however Choiseul began to see both countries as weak, France would need more formidable allies in Europe. Russia’s Empress also began to court an alliance with the French which would give her free reign over both Poland and the Ottoman Empire.

After Russia’s defeat of the Ottoman Navy at the Battle of Chesme, France suddenly began to reevaluate its position vis-à-vis the Ottoman Empire. The Count of Saint-Priest, French ambassador in Constantinople had made a blunt evaluation of the situation, reporting back to Choiseul on the weakness of the Ottoman Army. Also, beginning in 1770, the Russians had begun fomenting a revolt amongst the Greeks of the Ottoman Empire, particularly in Crete and Morea. However, the French did not want the Russians to have a presence in the Mediterranean. Saint-Priest warned that the Ottoman Empire was collapsing and that France should grab the pieces it could before it was too late. The Duc of Choiseul proposed to the king that France enter the war against the Ottomans so as to moderate the Russian gains, meanwhile depriving the British of an ally. Territorial acquisitions also came into play, as France had for a while now displayed ambitions towards annexing Crete.

The revolt amongst the Greeks and their suppression by the Ottomans became the pretext for intervention on behalf of the Christians of the Ottoman Empire. Since the reign of the Louis XIV, the French had appointed themselves as protectors of Christians in the sultan’s domains. In August 1770, a French fleet was assembled in Toulon with a force of 40,000 men to sail for Crete. After landing in Candia, the force faced little resistance and within a two days the Ottoman Pasha surrendered the island to the French. The Pasha departed and with him went several thousand Turks, fearing reprisals from the Greek population. After leaving behind a garrison on Crete of 6,000 men, the bulk of the French forces sailed for Morea, making a landing by September. The French army quickly achieved many victories, having captured Athens by December of 1770. The Russians too had secured the mouth of the Danube by that time.

Several states in Europe became alarmed by this war and what seemed like the end of the Ottoman Empire. The British for their part were shocked by the unforeseen chain of events. The French acquisition of Corsica in 1768 had brought down the government of the Duke of Grafton, and French acquisition of Crete would certainly precipitate another crisis. Though there were many in parliament who pressed for war, the American members of the House of Commons were vehemently against another conflict with France. They remembered the disaster the last war had brought upon the American provinces, along with the taxes they were still paying to reconstruct their defences. Another matter of concern was British dependence on Russia for its naval stores. If Britain were to go to war with Russia, the Royal Navy would be deprived of iron for its cannons, flax for its sailcloth, and most importantly timber for its masts and ships. Despite this, negotiations were underway at the beginning of 1771 with Austria, Sweden and Prussia to form a coalition against France and Russia.

Of all of the great powers, Austria was the most apprehensive about Russia’s gains as Russian troops were had secured Rumelia by the spring of 1771 and heading towards Constantinople. The French troops meanwhile had routed the Ottomans from Macedonia. However, Maria Theresa did not want a war with France. She hoped to strengthen the Franco-Austrian alliance. To that end, the Austrians rebuffed the British and negotiated secretly with the Russians and French for an agreement to acquire territory from the Ottomans as well. Finally, in October 1771, Austrian troops crossed the Danube into Serbia.

Prussia for its part was war-weary and still rebuilding its treasury from the last war. Therefore, the Prussians flatly rejected British attempts to go to war with France. The Prussians were more interested in Poland, and the Austrians along with the Russians seemed to be making progress at partitioning the kingdom. By 1771, the Russians and Austrians had agreed on the details of the partition and Prussia so no need to go to war with either Russia or Austria and risk losing its new acquisitions. The sacrifice of Poland on the part of the French, bought Prussian neutrality in the conflict. On September 1772, the annexation of Polish territory had been ratified by treaty and received the blessing of France. Meanwhile, in Sweden, the death of King Adolf Frederick had led to political turmoil throughout 1771 and 1772, preventing the Swedes from an alliance with Britain.

With the Russians approaching Constantinople, the Ottomans sued for peace in December of 1771. A peace treaty would be formalized in Belgrade in May 1772. The terms of capitulation ended up being much less harsh than expected, largely due to the infighting between Austria and Russia over the spoils of war. Russia had initially hoped for Rumelia, but this was blocked by both France and Austria. Austria for its part had wanted Bosnia too, but was restrained by the French.

In the end, Austria would receive Bukovina, Wallachia and Serbia, with the Austrian rulers now adding the titles of King of Serbia, Prince of Wallachia, and Duke of Bukovina to their already numerous titles. The French would acquire Morea and Crete, with the King of France now assuming the title of the King of Morea and Duke of Candia. Finally, Russia would annex Podolia, Bessarabia and Moldavia, now controlling the mouth of the Dniester. Finally, the Crimean Khanate was recognized as an independent state, however in reality it would be nothing more than a Russian puppet. Karbadia in the Caucasus was also recognized as a vassal of Russia. Other provisions included Russian protection over Orthodox subjects of the Porte, along with access to the Mediterranean.

Europe in 1776

Spanish West Africa

In 1777 and 1778, Portugal and Spain had signed treaties where they agreed on the frontiers of Brazil. Part of the agreement being that Portugal would cede the islands of Fernando Poo and Annobón in the Gulf of Guinea along with the rights to all land between the Niger River and the Ogooué River.

This was important because Spain had long had to rely on other nations for a supply of African slaves, with the Spanish Crown giving various companies an asiento or license to transport slaves. Portugal initially was the principal supplier, however, after 1713 Great Britain won that right for 30 years, as a spoil of the War of Spanish Succession. This agreement was cancelled by Spain in 1754, compensating the British South Sea Company with £100,000. Portugal and France now became the main suppliers.

The treaty of Tordesillas had excluded Spain from West Africa, however now it held the rights to some of the most lucrative slave trading regions on the continent including Calabar, Bonny, and Duala. A company from Cadiz had been awarded the Asiento in 1767, however it had no factories in Africa with which to supply slaves to the Spanish Caribbean, having to rely on buying them from Jamaica. With the new treaty in hand, the Spanish sent and expedition in 1780 from Rio de la Plata to claim the new territory.

When the Spaniards first arrived at Fernando Poo in 1780, they were greeted with a hostile reception from the native Bubi people on the island, having to send for a squadron of soldiers from Spain in 1781-1782 to pacify them. However, the island had few people and the Spaniards quickly began importing slaves from the mainland to work on sugarcane plantations. In 1790, cacao was introduced and by 1800 the island was one of the world's major producers.

On the mainland the Spaniards built factories at Cape Lopez and Duala. In Calabar they simply traded with the Efik people who would sell them captive slaves in return for a tribute to the local chief. However, in 1787 after the killing of 7 Spaniards, the Spanish retaliated by destroying Calabar. They followed up by building their own factory in 1789. Here the Spaniards also became leaders in the ivory trade in the following years.

Spanish America quickly developed a dependence on slave labour. The sugar plantations of Cuba, Puerto Rico and Santo Domingo initially took the most imports, this was soon followed by the sugar plantations of Veracruz and later New Navarra, Florida, and New Santander as these areas in northern New Spain became opened up to colonisation. Throughout 19th century slaves would be brought in huge numbers to Texas, New Navarra and California to work the cotton plantations as well.

In central America, slaves were brought to the Caribbean coast of Guatemala to work the sugar plantations there and in forestry and mining. In New Granada and Peru they would also work the mines. Many were also sent via Buenos Aires to the northern portions of the Viceroyalty of Rio de La Plata to work in mining and agriculture in remote areas.

By 1795, the Spaniards were exporting from Africa an average of 40-50,000 slaves to the New World each year. Young men between the ages of 10 to 25 were preferred, and would this group would account for nearly 70% of the slaves sold taken captive to the new world. The mortality rates during the passage were upwards of 10% for the slaves and over 5% for the sailors. In the New World itself, the sugarcane plantations proved to be the harshest places to work with the life expectancy of slaves there being about 25. Slaves working on a sugar plantation had a mortality rate 50% higher than those working in coffee plantations. Coupled with few slaves being able to reproduce or form families, this meant that the slave population in Spanish America had a negative natural growth rate of -5-8% per annum.

In Africa, the removal of so many people had an impact in Spanish Guinea. The areas under Spanish control, especially south of Duala had a negative growth rate due to women outnumbering men in many areas by 2 to 1. The introduction of manioc helped to mitigate the demographic impact somewhat, however by the 20th century, the area north of the Congo would be among the most sparsely populated areas of the African continent.

At the same time, Cadiz would grow rich from this human traffic, just as Liverpool and Nantes had.

In 1777 and 1778, Portugal and Spain had signed treaties where they agreed on the frontiers of Brazil. Part of the agreement being that Portugal would cede the islands of Fernando Poo and Annobón in the Gulf of Guinea along with the rights to all land between the Niger River and the Ogooué River.

This was important because Spain had long had to rely on other nations for a supply of African slaves, with the Spanish Crown giving various companies an asiento or license to transport slaves. Portugal initially was the principal supplier, however, after 1713 Great Britain won that right for 30 years, as a spoil of the War of Spanish Succession. This agreement was cancelled by Spain in 1754, compensating the British South Sea Company with £100,000. Portugal and France now became the main suppliers.

The treaty of Tordesillas had excluded Spain from West Africa, however now it held the rights to some of the most lucrative slave trading regions on the continent including Calabar, Bonny, and Duala. A company from Cadiz had been awarded the Asiento in 1767, however it had no factories in Africa with which to supply slaves to the Spanish Caribbean, having to rely on buying them from Jamaica. With the new treaty in hand, the Spanish sent and expedition in 1780 from Rio de la Plata to claim the new territory.

When the Spaniards first arrived at Fernando Poo in 1780, they were greeted with a hostile reception from the native Bubi people on the island, having to send for a squadron of soldiers from Spain in 1781-1782 to pacify them. However, the island had few people and the Spaniards quickly began importing slaves from the mainland to work on sugarcane plantations. In 1790, cacao was introduced and by 1800 the island was one of the world's major producers.

On the mainland the Spaniards built factories at Cape Lopez and Duala. In Calabar they simply traded with the Efik people who would sell them captive slaves in return for a tribute to the local chief. However, in 1787 after the killing of 7 Spaniards, the Spanish retaliated by destroying Calabar. They followed up by building their own factory in 1789. Here the Spaniards also became leaders in the ivory trade in the following years.

Spanish America quickly developed a dependence on slave labour. The sugar plantations of Cuba, Puerto Rico and Santo Domingo initially took the most imports, this was soon followed by the sugar plantations of Veracruz and later New Navarra, Florida, and New Santander as these areas in northern New Spain became opened up to colonisation. Throughout 19th century slaves would be brought in huge numbers to Texas, New Navarra and California to work the cotton plantations as well.

In central America, slaves were brought to the Caribbean coast of Guatemala to work the sugar plantations there and in forestry and mining. In New Granada and Peru they would also work the mines. Many were also sent via Buenos Aires to the northern portions of the Viceroyalty of Rio de La Plata to work in mining and agriculture in remote areas.

By 1795, the Spaniards were exporting from Africa an average of 40-50,000 slaves to the New World each year. Young men between the ages of 10 to 25 were preferred, and would this group would account for nearly 70% of the slaves sold taken captive to the new world. The mortality rates during the passage were upwards of 10% for the slaves and over 5% for the sailors. In the New World itself, the sugarcane plantations proved to be the harshest places to work with the life expectancy of slaves there being about 25. Slaves working on a sugar plantation had a mortality rate 50% higher than those working in coffee plantations. Coupled with few slaves being able to reproduce or form families, this meant that the slave population in Spanish America had a negative natural growth rate of -5-8% per annum.

In Africa, the removal of so many people had an impact in Spanish Guinea. The areas under Spanish control, especially south of Duala had a negative growth rate due to women outnumbering men in many areas by 2 to 1. The introduction of manioc helped to mitigate the demographic impact somewhat, however by the 20th century, the area north of the Congo would be among the most sparsely populated areas of the African continent.

At the same time, Cadiz would grow rich from this human traffic, just as Liverpool and Nantes had.

Naval Race of the 1780s.

Throughout the 1770s, the world's major navies had begun expanding. However, it was the major expansion in the French and Spanish navies during the following decade, that would prompt the other powers to begin launching new ships.

Amongst the Great Powers, the British were the most concerned by the Bourbons' naval expansion. They had become diplomatically isolated from the rest of Europe, and the Royal Navy was now expected to defend not only the British isles from a Franco-Spanish invasion, but secure British America, along with its valuable colonies in the West Indies and in India. During the last war, Britain had found itself unable to defend all of its territory, as most of its ships were stationed in the English channel to stave of an invasion. Also, on the continent, Austria, Russia and Prussia had turned out to be unreliable allies. Britain's smaller allies of Portugal and the Netherlands were no match for Spain and France.

However, with more revenue coming in from the American colonies, a rearmament programme was undertaken by the Royal Navy. To that end, between 1771 and 1774 a total of eleven ships of the line were launched. During the 1750s and 1760s the Royal Navy had entertained the idea of matching the massive three-decker ships of the line being launched by the Spanish Navy, with the 100-gun Royal George, Britannia and Victory. In addition, 11 90-gun ships and 1 98-gun ship were launched between 1755 and 1777. However, the Royal Navy soon turned to the cheaper to construct and faster 74-gun two deck ship of the line. These would be the majority of the Royal Navy ships after 1770, giving Britain a naval strength of 115 ships of the line by 1789. However, Britain would still rank behind France in naval strength. Though most ships were built in Britain, frigates were being launched in Portsmouth (New Hampshire), Boston, Philadelphia, and Newport in British America, this had proven popular with members of parliament from northern provinces of British America.

The French navy for its part began a major expansion programme during the reign of Louis XVI. The king was immensely interested in naval affairs and was determined to have a stronger navy that that of Britain's. Between 1780 and 1790, a total of 10 110-gun and 118-gun three-decker ships of the line were launched. By 1782, the French Naval budget was 250 million livres (£10.4 million), over double of Britain's total military expenditures. With the dockyards of France unable to keep up with production, Québec and Saint-Jean produced nearly half of France's large ships during this period. In France itself, Rochefort and Lorient also became major dockyards for France's navy during this period. By 1789, the French navy would be the largest in the world with 128 ships of the line.

Spain's tax reforms had given the Spanish Crown the ability to raise revenue substantially during the wars in North Africa. To that end the Spanish rebuilt their navy and military, with a naval budget of 140 million reales (£3.8 million) by 1784 . The Spanish had focused on larger heavier ships with substantial fire power to protect their far flung empire. Havana became the dockyard launching the large 112-gun ships like the Santísima Trinidad in 1769. By 1789, the Spanish Navy would have largest number of three-deckers with 14 in her fleet. However, the Spanish too followed the lead of over navies launching many 74-gun ships. By 1789, Spain's navy ranked third amongst the world's naval forces with 88 ships of the line.

The Dutch Navy too recovered from a long decline during the 1780s. However, France's annexation of the Austrian Netherlands, coupled with Britain's defeat during the last war preoccupied the Dutch Republic into rebuilding a formidable navy. Due to the shallower waters around the Netherlands, they preferred to rely on smaller ships in the 60-gun range along with frigates. By 1789, the Dutch Navy had 50 ships of the line, securing the title of the world's fourth largest navy.

The Russian fleet had expanded considerably with with 7 100-gun ships being launched in the 1780s for use in the Black Sea and subsequently the Mediterranean. In addition to that 17 74-gun ships were launched, adding to the several smaller ships based in the Baltic. By 1789, the Russian Navy possessed 38 ships of the line. It had risen from nearly nothing to an impressive fifth place.

Like the Dutch, the Portuguese found themselves in a vulnerable after Britain's defeat. To that end they sought a policy of neutrality, trying to cooperate with Spain and France wherever possible. Also, the Portuguese crown found itself having to emulate Spain's taxes on land-holdings to raise revenues. This did have the effect of increasing the budget and allowing the navy to expand to 28 ships of the line by 1789, including 3 large 84-gun ships. The Portuguese Navy's main task during this period was to protect convoy's from Brazil and also to counteract Arab piracy in the Indian Ocean and in the Persian Gulf, as the Omanis along with smaller states posed a threat to both Mozambique and Goa.

The Danish Navy would rank seventh just behind the Portuguese. However, with the shallower waters of the Baltic, they like the Dutch stuck to building smaller 50 and 62-gun ships along with frigates to defend Denmark and Norway. By 1789, the Danish Navy possessed 24 ships of the line.

The Swedish Navy had fallen behind due to the instability in that country during this period. However, they were alarmed at Russia's rapidly growing navy. To that end 10 62-gun ships of the line were launched during the 1780s. By 1789, Sweden possessed 17 ships of the line.

The Kingdom of Naples and Sicily ranked last among the world's 8 large navies. However, there were some ships launched and by 1789 they possessed a navy of 12 ships of the line, giving the Kingdom the ability to defend itself against the pirates of the Barbary Coast.

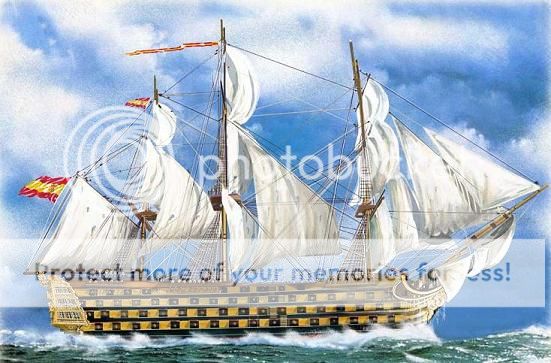

Spain's 112-gun Nuestra Señora de la Santísima Trinidad

Throughout the 1770s, the world's major navies had begun expanding. However, it was the major expansion in the French and Spanish navies during the following decade, that would prompt the other powers to begin launching new ships.

Amongst the Great Powers, the British were the most concerned by the Bourbons' naval expansion. They had become diplomatically isolated from the rest of Europe, and the Royal Navy was now expected to defend not only the British isles from a Franco-Spanish invasion, but secure British America, along with its valuable colonies in the West Indies and in India. During the last war, Britain had found itself unable to defend all of its territory, as most of its ships were stationed in the English channel to stave of an invasion. Also, on the continent, Austria, Russia and Prussia had turned out to be unreliable allies. Britain's smaller allies of Portugal and the Netherlands were no match for Spain and France.

However, with more revenue coming in from the American colonies, a rearmament programme was undertaken by the Royal Navy. To that end, between 1771 and 1774 a total of eleven ships of the line were launched. During the 1750s and 1760s the Royal Navy had entertained the idea of matching the massive three-decker ships of the line being launched by the Spanish Navy, with the 100-gun Royal George, Britannia and Victory. In addition, 11 90-gun ships and 1 98-gun ship were launched between 1755 and 1777. However, the Royal Navy soon turned to the cheaper to construct and faster 74-gun two deck ship of the line. These would be the majority of the Royal Navy ships after 1770, giving Britain a naval strength of 115 ships of the line by 1789. However, Britain would still rank behind France in naval strength. Though most ships were built in Britain, frigates were being launched in Portsmouth (New Hampshire), Boston, Philadelphia, and Newport in British America, this had proven popular with members of parliament from northern provinces of British America.

The French navy for its part began a major expansion programme during the reign of Louis XVI. The king was immensely interested in naval affairs and was determined to have a stronger navy that that of Britain's. Between 1780 and 1790, a total of 10 110-gun and 118-gun three-decker ships of the line were launched. By 1782, the French Naval budget was 250 million livres (£10.4 million), over double of Britain's total military expenditures. With the dockyards of France unable to keep up with production, Québec and Saint-Jean produced nearly half of France's large ships during this period. In France itself, Rochefort and Lorient also became major dockyards for France's navy during this period. By 1789, the French navy would be the largest in the world with 128 ships of the line.

Spain's tax reforms had given the Spanish Crown the ability to raise revenue substantially during the wars in North Africa. To that end the Spanish rebuilt their navy and military, with a naval budget of 140 million reales (£3.8 million) by 1784 . The Spanish had focused on larger heavier ships with substantial fire power to protect their far flung empire. Havana became the dockyard launching the large 112-gun ships like the Santísima Trinidad in 1769. By 1789, the Spanish Navy would have largest number of three-deckers with 14 in her fleet. However, the Spanish too followed the lead of over navies launching many 74-gun ships. By 1789, Spain's navy ranked third amongst the world's naval forces with 88 ships of the line.

The Dutch Navy too recovered from a long decline during the 1780s. However, France's annexation of the Austrian Netherlands, coupled with Britain's defeat during the last war preoccupied the Dutch Republic into rebuilding a formidable navy. Due to the shallower waters around the Netherlands, they preferred to rely on smaller ships in the 60-gun range along with frigates. By 1789, the Dutch Navy had 50 ships of the line, securing the title of the world's fourth largest navy.

The Russian fleet had expanded considerably with with 7 100-gun ships being launched in the 1780s for use in the Black Sea and subsequently the Mediterranean. In addition to that 17 74-gun ships were launched, adding to the several smaller ships based in the Baltic. By 1789, the Russian Navy possessed 38 ships of the line. It had risen from nearly nothing to an impressive fifth place.

Like the Dutch, the Portuguese found themselves in a vulnerable after Britain's defeat. To that end they sought a policy of neutrality, trying to cooperate with Spain and France wherever possible. Also, the Portuguese crown found itself having to emulate Spain's taxes on land-holdings to raise revenues. This did have the effect of increasing the budget and allowing the navy to expand to 28 ships of the line by 1789, including 3 large 84-gun ships. The Portuguese Navy's main task during this period was to protect convoy's from Brazil and also to counteract Arab piracy in the Indian Ocean and in the Persian Gulf, as the Omanis along with smaller states posed a threat to both Mozambique and Goa.

The Danish Navy would rank seventh just behind the Portuguese. However, with the shallower waters of the Baltic, they like the Dutch stuck to building smaller 50 and 62-gun ships along with frigates to defend Denmark and Norway. By 1789, the Danish Navy possessed 24 ships of the line.

The Swedish Navy had fallen behind due to the instability in that country during this period. However, they were alarmed at Russia's rapidly growing navy. To that end 10 62-gun ships of the line were launched during the 1780s. By 1789, Sweden possessed 17 ships of the line.

The Kingdom of Naples and Sicily ranked last among the world's 8 large navies. However, there were some ships launched and by 1789 they possessed a navy of 12 ships of the line, giving the Kingdom the ability to defend itself against the pirates of the Barbary Coast.

Spain's 112-gun Nuestra Señora de la Santísima Trinidad

To be honest, the Franco-Spanish alliance is beginning to look like an unstoppable juggernaut. What a price for the British Empire to pay in exchange for keeping the Thirteen Colonies!

About the only thing that could stop France at this point is a bloody revolution...

Why Revolution?

Usually, when the country is doing well, the people are not so angry. And even they are disgruntled, as far major famines and huge deficits can be avoided (with the money from colonies) it will be manageable. Plus, a greater emigration to the colonies will be a good way to disperse tensions.

The Bourbon monarchy should only keep the peasants feed and win wars (no stupid peace) and do minor and continues reforms (like British OTL).

I still have one question, are the Spanish also Bourbons ?

Thanks and keep going!

Uff Da the optimist

Donor

Me too, just re-read it and would really like to see what the future holds!!

BRITANNIA ASCENDANT

Despite Britain's defeat at the hands of the French in 1758, by 1783 the twenty-five years of peace had allowed Britain and its North American colonies to not only recover, but to thrive both politically and economically. The British economy had grown due to increasing mechanisation as the Industrial Revolution was underway. Commerce also increased and Britain's financial system was among the best in Europe as London now became a financial hub. Even France, though much larger could not compete. France with its cottage industries tended to produce high-quality luxury goods on a smaller scale, rather than relying on mass-production, in contrast with Britain's increasingly cheaper mass produced goods. During this period, British tariffs were lowered, allowing for increased trade within the empire, so that tobacco, sugar and tea consumption increased in Britain, whereas France was still relying on a mercantilist economic system. Canal building was in Britain was more important than ever, along with coal mining and the profusion of new steam-powered textile mills. As a result, Britain's merchant classes became the most politically influential in Europe, with their political clout only rivaled by Dutch merchants in Amsterdam.

Politically, Britain remained under Tory rule in 1783 with the accession of William Pitt the younger as Prime Minister. He sought to continue several of the political reforms which had been enacted by the previous government under Lord North. Among these, was the granting of a constitution to Ireland in 1782. This having followed the establishment of a written constitution for America in 1780. The difference being that America continued to elect Members to the House of Commons, while Ireland had complete legislative independence.

In 1784, the India Act reformed the British East India Company, helped centralise British India under the Governor-General based at Calcutta, with subordinates in Bombay and Fort Saint George. Increased taxes in both Britain and America were seen as a necessary evil to protect the British Empire from France and Spain and were allowed for a reduction of the national debt and most importantly for the rebuilding of the Royal Navy, with several new ships being launched during the 1770s and 1780s. Perhaps the most notable reform undertaken by Pitt was the Parliamentary Reform Act of 1786, whereby several rotten boroughs were abolished. The act was passed with near unanimity of the American MPs, abolishing several of the rotten boroughs with provisions to compensate others. This resulted in a redistribution of 72 seats in the house, with the most important effect being the increasing political representation in the growing commercial ports of the country like Liverpool.