You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Civilian Jetliners of Alternate History

- Thread starter George Carty

- Start date

American aero companies should have considered taking a page from Barnes Wallis's book and designed a relatively low-speed SST, in the Mach 1.5 range or so, first. I guess by the early Sixties they figured their transAtlantic competition would already have a Mach 2 passenger jet to offer the public and that they had to leapfrog past that. But I'd think that by 1960 they'd have a lot of experience with relatively low supersonic speeds thanks to military fighters and planes like the B-58 "Hustler" bomber, and so whipping up a suitable passenger plane much sooner than the Concorde could come to market would get their foot in the door sooner.

More to the point, around Mach 1.5, the thermal heating in the shock wave is about the right amount to raise stratospheric air to temperatures comparable to those prevailing here on the ground, so either no unusual air conditioning would be needed or at any rate it would be modest. Still more importantly, the temperatures the plane would operate in would be similar to those normal airplanes experience and so standard materials could be reliably used. The aerodynamic compromises between decent supersonic and acceptable subsonic performance (for acceptable takeoff/landing conditions) would be less than for the faster planes too.

The joker in the deck is that while both airframe performance (attainable lift/drag ratio, that is) and engine performance worsen as you push the top speed higher, they don't do so in direct proportion to speed. So if you can make an engine and airframe that can go at Mach 2, it will use more fuel per minute than one that can operate at Mach 1.5, but not 33 percent more, so you wind up with slightly better economy at the faster speed--assuming everything else stays equal which has been pointed out here is not the case. You need a heavier airframe to go faster, which also complicates takeoff and landing. But there is that economic temptation to pioneer ever-higher speeds, which would also reward whoever gets there firstest with the mostest with pre-empting market share.

In hindsight, clearly Concorde was too big a step forward for its day, and given that today there are no SSTs flying for anyone (unless the Russians revive theirs, but I gather those Tupolevs were grounded long ago, not long after they launched in fact) perhaps the time has come to revisit Wallis's modest proposal to begin modestly. Certainly a Mach 1.4 transoceanic liner would be very noticeably faster than anything anyone else has to offer. Given that today aero firms have decades more experience with supersonic military planes, lots of advanced materials, supercruise engines, etc, it ought to be doable as a private venture.

I don't say that it would necessarily be economical, not even sold to a premium market. (Perhaps it would be better to invest in high passenger volume and aim for a mass market instead).

We also have heard tell here on this thread of commercial supersonic business jets; not clear to me if any of them are actually flying or offered for sale yet. I haven't noticed a military executive jet version for anyone's Air Forces, so that casts some doubt on how market-ready any of these can be as of today. But if a version is sold and has decent success I suppose it could lead directly to at least a small and expensive-ticketed common carrier.

More to the point, around Mach 1.5, the thermal heating in the shock wave is about the right amount to raise stratospheric air to temperatures comparable to those prevailing here on the ground, so either no unusual air conditioning would be needed or at any rate it would be modest. Still more importantly, the temperatures the plane would operate in would be similar to those normal airplanes experience and so standard materials could be reliably used. The aerodynamic compromises between decent supersonic and acceptable subsonic performance (for acceptable takeoff/landing conditions) would be less than for the faster planes too.

The joker in the deck is that while both airframe performance (attainable lift/drag ratio, that is) and engine performance worsen as you push the top speed higher, they don't do so in direct proportion to speed. So if you can make an engine and airframe that can go at Mach 2, it will use more fuel per minute than one that can operate at Mach 1.5, but not 33 percent more, so you wind up with slightly better economy at the faster speed--assuming everything else stays equal which has been pointed out here is not the case. You need a heavier airframe to go faster, which also complicates takeoff and landing. But there is that economic temptation to pioneer ever-higher speeds, which would also reward whoever gets there firstest with the mostest with pre-empting market share.

In hindsight, clearly Concorde was too big a step forward for its day, and given that today there are no SSTs flying for anyone (unless the Russians revive theirs, but I gather those Tupolevs were grounded long ago, not long after they launched in fact) perhaps the time has come to revisit Wallis's modest proposal to begin modestly. Certainly a Mach 1.4 transoceanic liner would be very noticeably faster than anything anyone else has to offer. Given that today aero firms have decades more experience with supersonic military planes, lots of advanced materials, supercruise engines, etc, it ought to be doable as a private venture.

I don't say that it would necessarily be economical, not even sold to a premium market. (Perhaps it would be better to invest in high passenger volume and aim for a mass market instead).

We also have heard tell here on this thread of commercial supersonic business jets; not clear to me if any of them are actually flying or offered for sale yet. I haven't noticed a military executive jet version for anyone's Air Forces, so that casts some doubt on how market-ready any of these can be as of today. But if a version is sold and has decent success I suppose it could lead directly to at least a small and expensive-ticketed common carrier.

The Aerion supersonic biz-jet is scheduled to be real in 2014. Cruise is Mach 1.7. 12 passengers. A 50 passenger vehicle is said to be in the offing.

The Burnelli lifting body GB-888A was designed by Vincent Burnelli before his death in 1964. His story is quite interesting, and his designs make one wonder of the reason they didn't receive more acceptance in the mainstream, although many of his patent ideas seem to have been borrowed.

The Burnelli lifting body GB-888A was designed by Vincent Burnelli before his death in 1964. His story is quite interesting, and his designs make one wonder of the reason they didn't receive more acceptance in the mainstream, although many of his patent ideas seem to have been borrowed.

Why then did the OTL Soviet Union have markedly different airliner design from the West?

Another Soviet oddity was the Yakovlev Yak-40 -- this aircraft was a jet designed for really bad runways, where Western countries would use only propeller planes. On the other hand it certainly wasn't a fast jet...

Mainly because the Soviet design bureaux (Tupolev, Ilyushin, Yaklovev) didn't do the actual research involved in aircraft production. That function was taken by TsAGI, the Central Aero- and Hydrodynamics institute. A good analogy would be if American aircraft design houses had to get their aerodynamic data from NASA, instead of in-house.

The second reason Soviet designs were so different is that they were developed to a different set of requirements. As has already been mentioned, in the Soviet era (and continuing in some places to today) most airports would be considered "unimproved" or "unusable" to Western aviation authorities. Even at that, some major airports were almost completely lacking in most sorts of ground-support facilities. To that end, airliners in the Soviet Union had to be able to operate from awful-condition airfields, turn-around at the airport had to be almost completely independent, and return to awful-condition airfields with the minimum of maintenance in the interim. Even the Tu-144 had a rough-field capability

A further note on the "self-sufficiency" aspect: Soviet airliners have some abilities that were rarely seen in Western types. The Il-86, a Soviet analogue to the early widebodies such as the L-1011 and DC-10, has not only an APU powerful enough to power all the aircraft's systems (including de-icing) for an extended period but also suction pumps for aiding in refueling, and a unique ground-access ability where passengers enter the lower level through several sets of self-contained airstairs, stow their own luggage, and then ascend to the upper passenger-seating level. The only large Western airliner to offer this facility, to my knowledge, was the L-1011 and even then on a very limited basis. And even after all this the Il-96 is still able to take off and land from gravel airstrips.

Probably the main reason Soviet airliners were never able to compete on a level playing field with those of the West, though, came down to powerplants. Soviet jet engines were, in short, maintenance nightmares and hideously inefficient. Powerful to be certain but the Soviet engine designers were never able to balance power with efficiency. Again referring the the Il-86, the Soloviev engines it used were so far behind equivalent Western types that four engines were needed and at that it's range was far below what a large widebody of the early Eighties would be expected of in the West. It was not until the improved Il-96 that this was rectified when it was re-engined with the PS-90A but by then the die had been cast.

(Partisan alertCanada's Avro Jetliner C-102. It could have established Canada as a major producer of passenger jet planes - for a few years.

It didn't help nobody at Avro or DND could see the increased production of the Clunk wouldn't arrive for years. In the event, the war was over, first.Oddly enough, it was defense spending that killed the Canadian one. Or rather defense production capacity: Avro simply couldn't build both the CF-100 Canuck fighter and the Jetliner at once, and with a war on C.D. Howe ordered the company to build fighters.

FYI, this was part of why the C.102 had underslung engines: the gear legs could be short, & engine maintenance done without special rigs. It also enabled engines to be installed without substantial spar changes IIRC (which, IIRC, the podded design required).Not all aircraft designers think to hard about maintenance issues

Last edited:

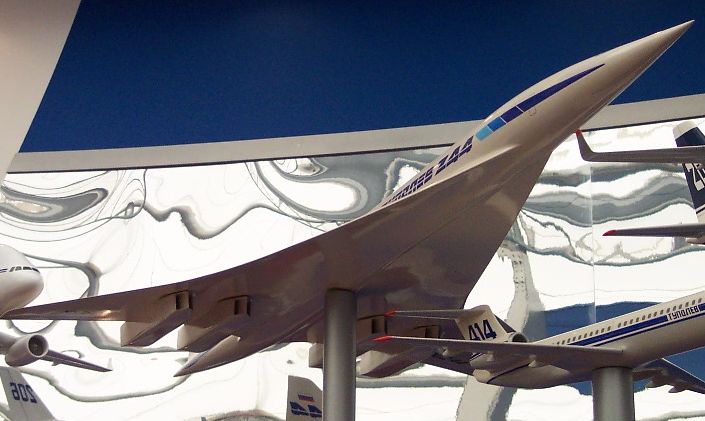

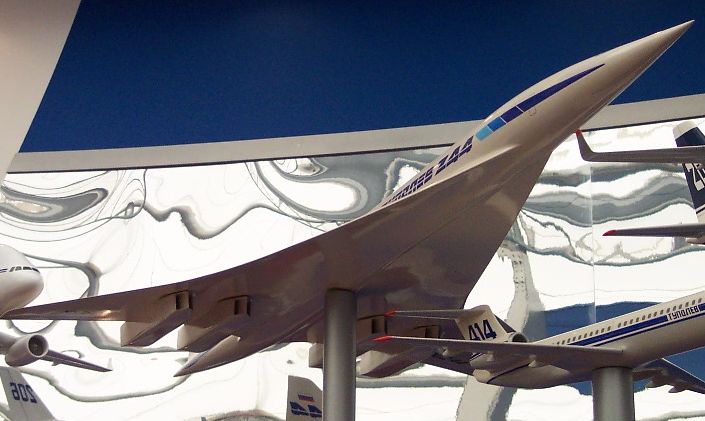

Also, the Tupolev Tu-244, a proposed successor of the Tu-144 - here's a mockup :

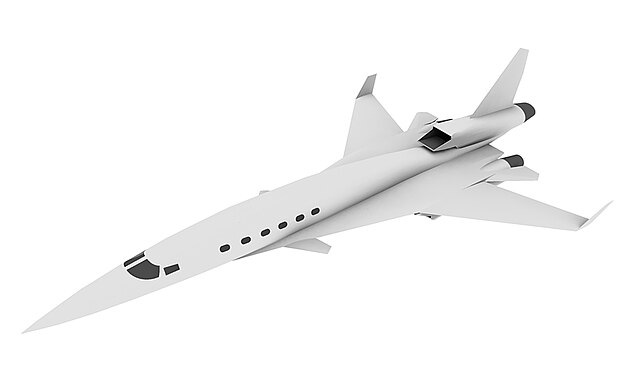

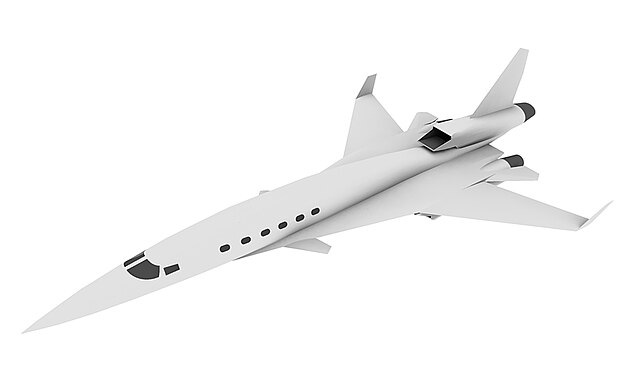

And, in the grand tradition of early 90s euphoria over Russia jettisoning its Soviet paintjob, here's a joint American-Russian project, the Sukhoi-Gulfstream S-21 business jet :

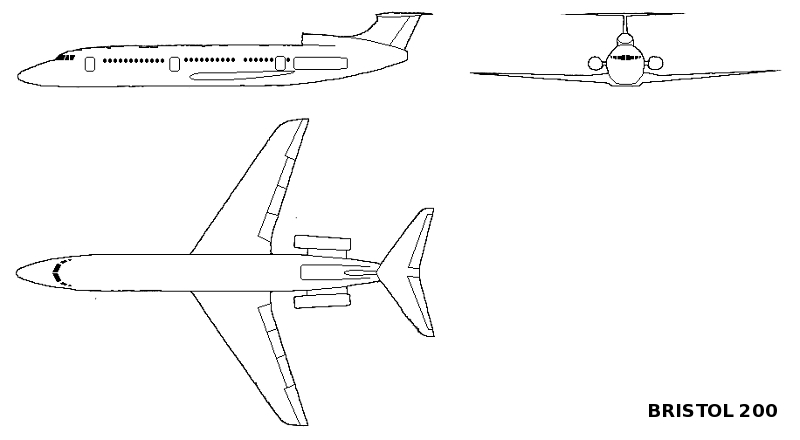

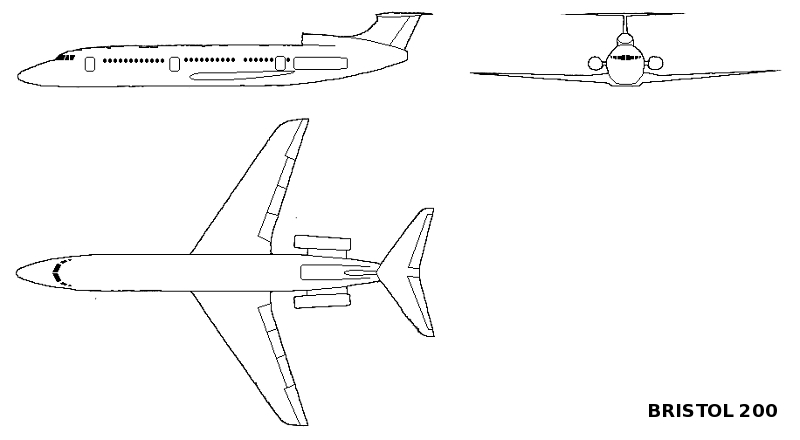

A British unbuilt proposal from 1956 was the Bristol Type 200 :

And, in the grand tradition of early 90s euphoria over Russia jettisoning its Soviet paintjob, here's a joint American-Russian project, the Sukhoi-Gulfstream S-21 business jet :

A British unbuilt proposal from 1956 was the Bristol Type 200 :

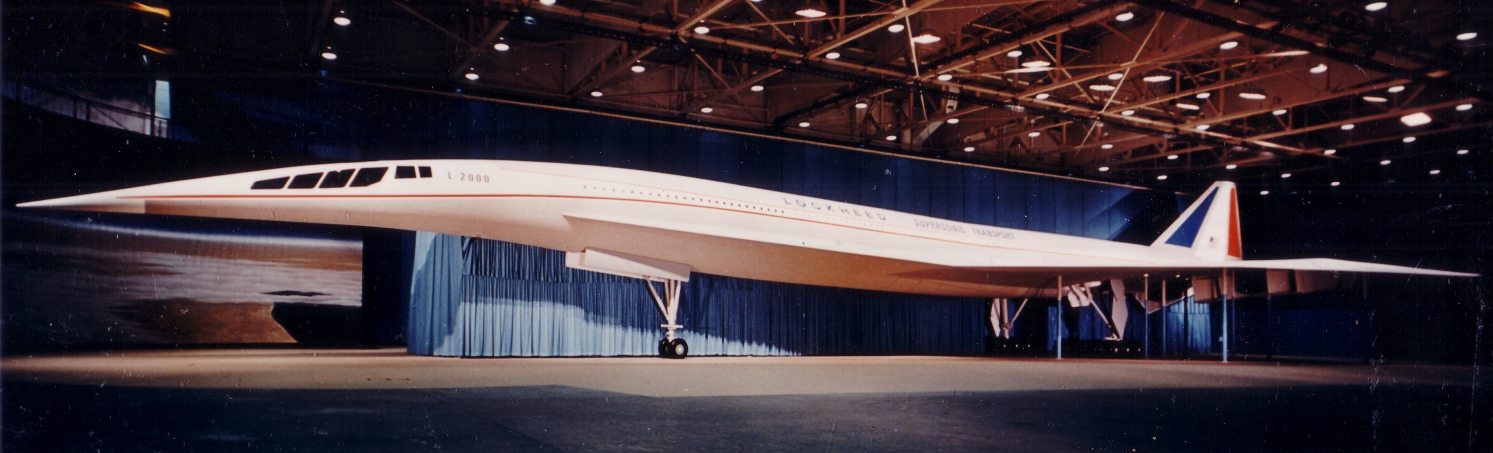

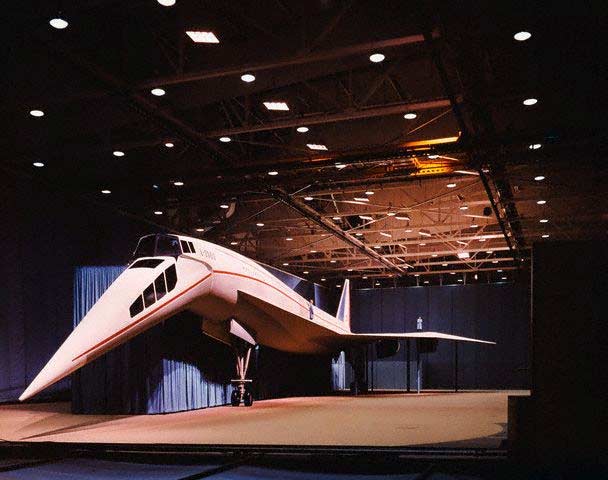

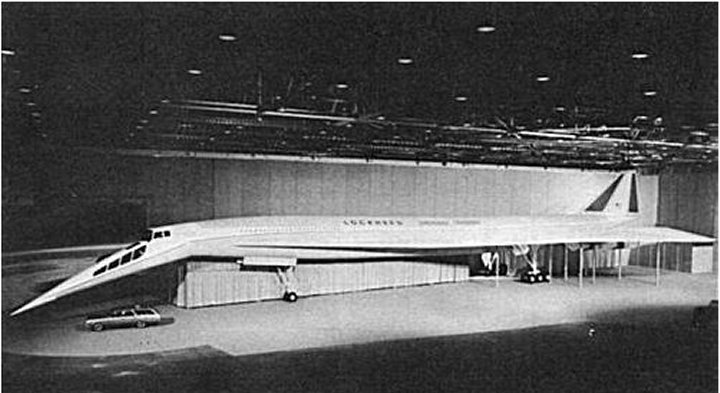

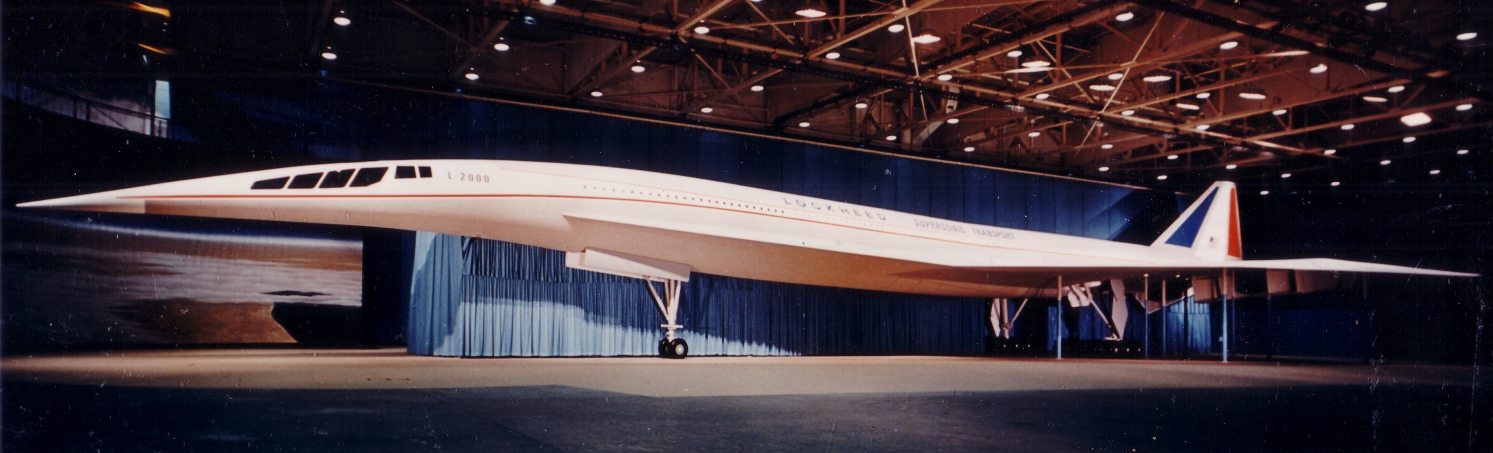

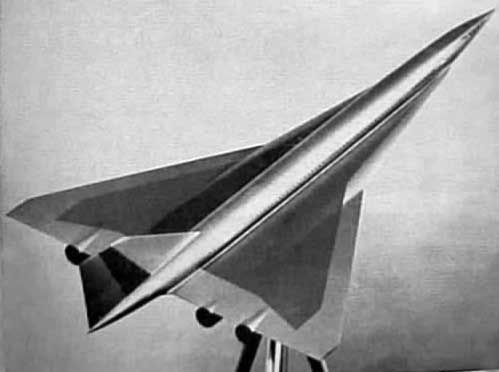

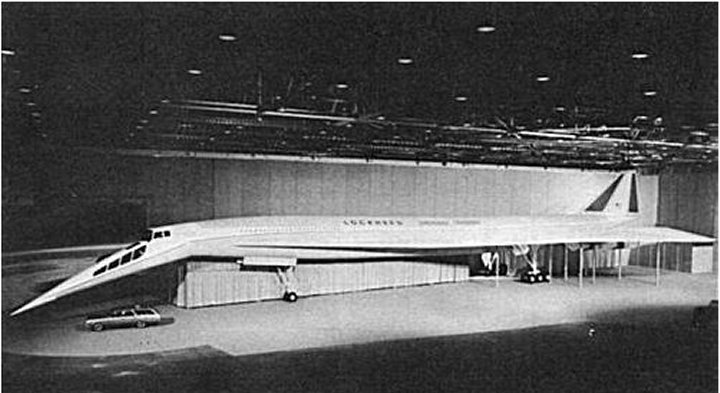

A video showcasining the mockups of cancelled late 60s US supersonic airliners, the Lockheed L-2000 and the Boeing 2707 :

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HV7K2BHNMoc

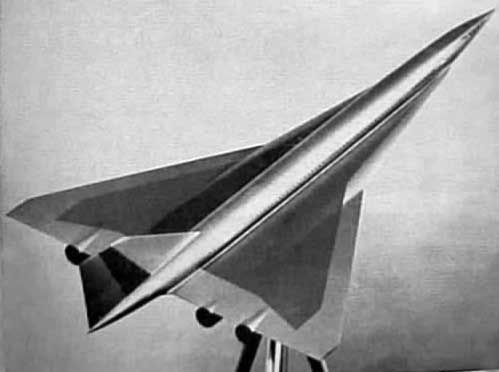

Lockheed L-2000 :

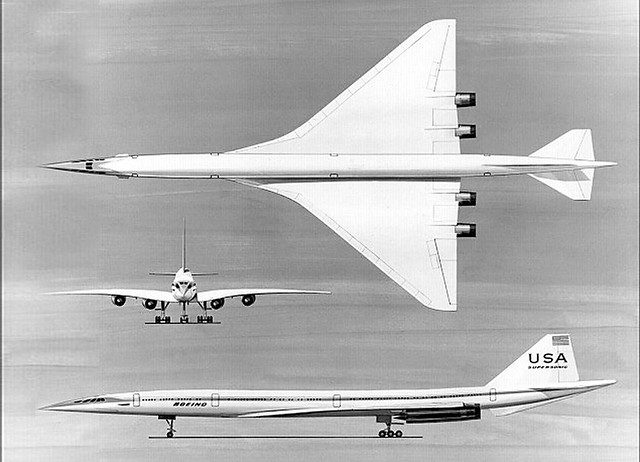

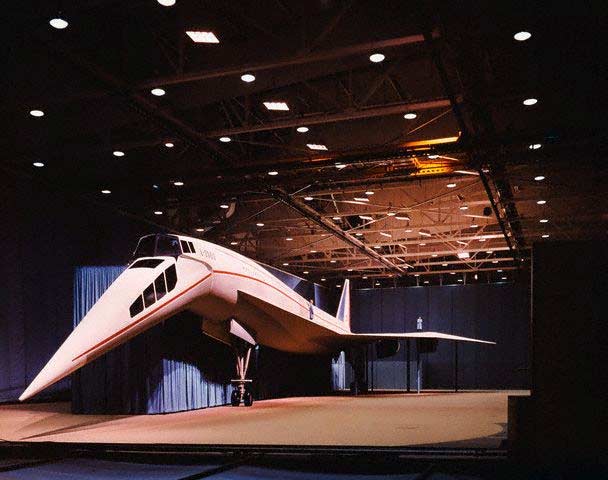

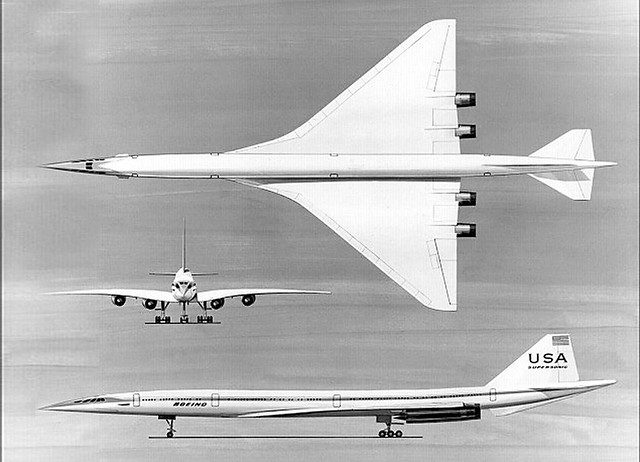

Boeing 2707 :

As crazy as it sounds, it had variable-sweep wings.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HV7K2BHNMoc

Lockheed L-2000 :

Boeing 2707 :

As crazy as it sounds, it had variable-sweep wings.

Sorry for the necro, but this is too interesting a thread to leave for dead.

Since pictures of some of the planes mentioned in the first few posts didn't get posted, I'm remedying that problem - here's the Fokker F.26 "Phantom" in all its glory...

Thank you for drawing my attention to this concept.

Now, in the name of all that is holy, what were they thinking of putting the jet engines on the very bottom of the plane like that??

Reading up on it, I got 2 "answers":

1) it would make the cabin quieter

2) easier to maintain.

Well to 1), I don't see how it would be any quieter than if they'd put them up on top of the fuselage, or out on the wings for that matter. Wouldn't they actually be quieter in the position Boeing sanctified?

2)--yes, surely, putting the engines practically on the runway would make them easier to reach.

It also makes it much much much easier for all manner of runway debris to reach the engines, get sucked in and shred their innards.

Surely they weren't unaware of the possibility?

To be sure, having invoked Boeing to point out the wisdom of putting the engines in pods out on the wing, I have to face up to the Boeing 737, which put those pods below an already low-mounted wing, so close to the ground that when they wanted to upgrade to turbofans that needed greater airflow to work with they had to make the intakes oval because there just wasn't any more room to widen them in an up-down direction!

Boeing did have to take some extraordinary measures to protect those low jet engine intakes from FODs, including IIRC installing a blower system to blow down any debris popping up to enter the engines.

The Fokker is even worse than the 737 in this respect.

Fokker also designed, with VFW, the bizarre VFW-Fokker 614, which had it's engine pods above the wings.

*googles picture*

Oh my !

*googles picture*...

Oh my !

Why, Petike, I've gotten the impression you knew of everything that ever flew or was designed to fly; it's amazing to see something that surprises you!

The difference here is, the 614 works. It looks bizarre, but those high engines sheltered behind the wing leading edge are a great idea. They enabled the little airplane to be designed very low to the runway, meaning shorter landing gear and easier access for passengers and cargo.

I'm sad they didn't sell more models than the relative handful they did.

The above-mentioned Caravelle system of tail-mounted engines of course gets similar results and has been very popular, with the Caravelle itself selling well and with numerous foreign (to France) competitors picking up on the idea, in the USA, in Britain, and in the USSR. Oh and apparently Fokker too!

I guess I should be less harsh with the F.26; while I can't think of any multi-engine transport that puts the air intakes down on the deck like that, I sure can think of lots of fighter planes, including that USAF and export workhorse the F-16, that do something similar with chin intakes. I guess it just looks different on a subsonic transport than on a supersonic jet!

Why, Petike, I've gotten the impression you knew of everything that ever flew or was designed to fly; it's amazing to see something that surprises you!

Not at all. Better to look in a dictionary than be a dictionary, as the old saying goes.

An upside-down Fokker 26 is the AN-72. STOL characteristics and a poor seat/mile cost. It doesnt hoover FOD.

A very similar design was independently developed by Boeing for their YC-14. The Air Force dropped the STOL tactical airlift contract it was designed for, however, and the eventual C-17 specification was more suited to a more conventional design like the competing McDonnell Douglas YC-15.

An upside-down Fokker 26 is the AN-72. STOL characteristics and a poor seat/mile cost. It doesnt hoover FOD.

The AN-72 and YC-14 both use the engine placement to run strong airflow over the wing and use the Coanda effect to achieve very high lift coefficients for low-speed takeoff and landing. As STOL planes one wouldn't expect them to manage high cruise efficiency as well!

In the early days when the F.26 was conceived I don't know that anyone would have been thinking in those terms and anyway the method involves designing wing flaps that can take being in the direct blast of the engines, probably not a good thing to try in 1946! Also in the '40s, although the idea of the turbofan had already been thought up and both Francis Whittle and Metropolitan Vickers had sketched out designs for them, no one was actually making any. The more modern planes used turbofan engines that would have a slower and cooler (though more massive) exhaust that it is somewhat easier to design those flaps for; in 1946 the basic turbojets available would have a much hotter and faster exhaust that perhaps we couldn't adapt for purposes of circulation control even today.

So if they'd put the engines on top instead of on the bottom, it would have only been to get them up and out of the way of FODs and they'd have had some problems with the jet exhaust sticking to the wings and thus overheating them, and also impinging on the tail surfaces, and for that matter sticking to the upper fuselage.

Still that sort of design was considered in those days, I believe that before Boeing massively revised their initial designs for what would become the B-47, they were going with straight wings and engines right on top of the fuselage at the wing root. In fact they were going to bury them in the upper fuselage. One reason they gave up on that was Air Force people reminding them what happens when a jet engine fails and flies apart; the USAF guys did not want the engines inside along with the bomb load and at the most crucial part of the structure! The Fokker design, with the two engines either below or above, looks less fatal than that, with the engines clearly outside the main structure.

If they were going to move the engines up I'd think they'd want to move the wings down, to keep them cleanly separated; that also brings the wings down to where wing-mounted landing gear are possible.

Obviously the STOL planes, East and West, couldn't do that because there the idea is to bring engine exhaust together with the wing.

If the F.26 design had been switched around like that I'd have been less flabbergasted by it. I still don't see how they could think it would be quiet but I didn't see that with the engines on the bottom either. It certainly would be harder to access the engines for maintenance though.

I was going to start a new thread but this appears to be a good place to ask as we seem to have several knowledgeable people knocking about. As most people know the de Havilland Comet was the worlds first jet airliner that looked to be about to take over the global market for a number of years until a series of accidents thanks to the at the time unknown factors of stress and metal fatigue caused a number of accidents grounding the fleet and forcing a number of modifications. The lead that they had built and reputation were lost and never really recovered. The three main factors that contributed to the crashes were the use of a thinner gauge metal, square windows where stress concentrations built up, and the use of punch rivet construction in general and instead of glue around the windows. However under the original plans the Comet was meant to of used drill riveting and glued windows that are much less susceptible to fatigue cracks, I could of also of sworn that I'd read somewhere that originally the windows were meant to be rounded instead of square but can't find anything now so could well be mistaken.

So to get to the alternate history part what happens if de Havilland decides to stick to the plans they came up with and use drill riveting and glue as originally intended. Is this enough to push back the rate of metal fatigue that they're able to control the market for longer, and perhaps even see Boeing and Douglas produce their 707 and DC-8 respectively with similar design flaws since as they later said they learnt it from the Comet? Or would we need to increase the gauge of the skin and have rounded windows? And if so could we possibly get away with doing just one or the other to extend the initial life of the plane? Thanks.

So to get to the alternate history part what happens if de Havilland decides to stick to the plans they came up with and use drill riveting and glue as originally intended. Is this enough to push back the rate of metal fatigue that they're able to control the market for longer, and perhaps even see Boeing and Douglas produce their 707 and DC-8 respectively with similar design flaws since as they later said they learnt it from the Comet? Or would we need to increase the gauge of the skin and have rounded windows? And if so could we possibly get away with doing just one or the other to extend the initial life of the plane? Thanks.

One can presume that contributory factors are cumulative and that the Comets would have lasted longer with a partial cure. I can't imagine much good stemming from having more Comets in service when they start to fail. The Comet's failure was instrumental in initiating investigation into fail-safe methods of construction whereby failure is detected before it becomes catastrophic. Delaying such wouldn't be a good thing. To this day, people often have to die before unprofitable measures are taken to detect and prevent flawed aircraft and components.

The fate of the Comet and especially of a far luckier turn in its development has been discussed a lot over the years. It is true that the British aerospace industry needlessly lost a lot of steam in the late 50s and early 60s and never fully recovered from that period, both in the civilian and military aviation market. I'm sure the Comet could have been more succesful and gain increasingly better variants over the years, but I'm not so much sure how this would influence competing American, French, German/Dutch and Russian manufacturers.

Share: