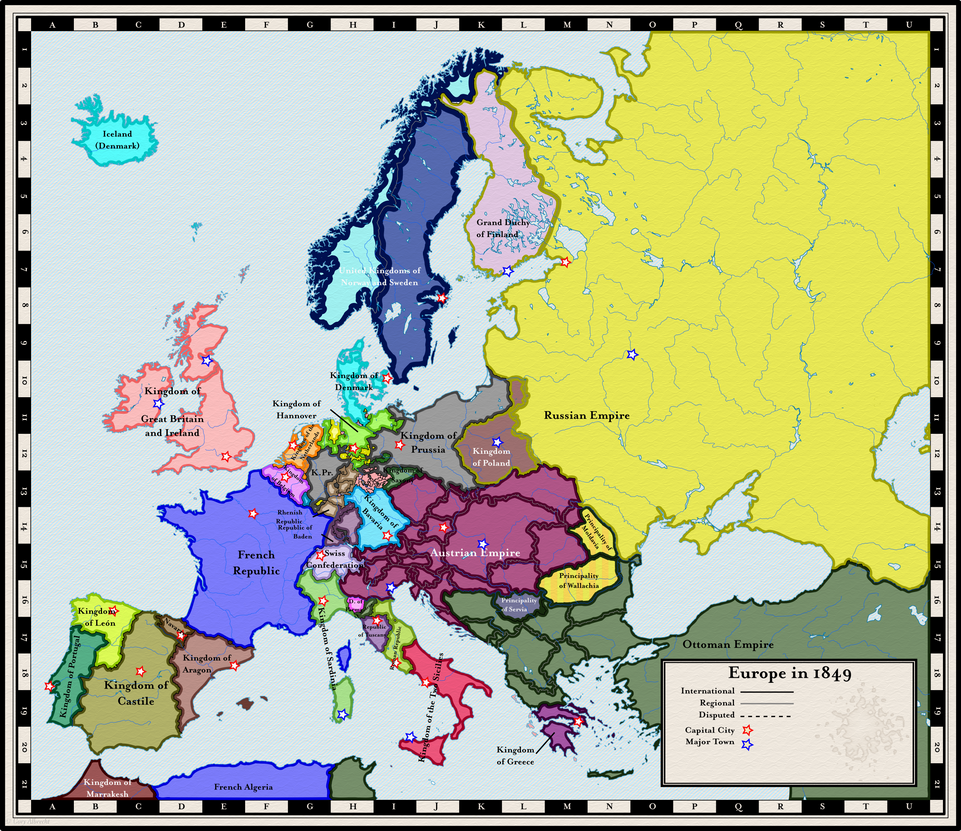

Europe and the Balance Power, Part III, 1848-1849

After nearly a decade of relative quiet, 1848 and 1849 are two very chaotic years for Europe.

In January, the island Kingdom of Sicily is wracked by rebellion against Neapolitan control and later that spring declares itself independent of the Kingdom of Naples. King Ferdinand II, initially favoured by the common folk, has become less popular since beginning his reign and is dealing with problems on the peninsula as well. He is forced to grant the Kingdom of Naples a liberal constitution. A force is sent to Sicily and in a bloody war lasting nine months, Frederick II reasserts his control. From then on, both his Kingdoms are the subject of rumour through Europe regarding their mismanagement and poverty which are only given more substance by the stories of repression by the secret police told by the many Sicilian and Neapolitan immigrants to the New World.

Grand Duke Leopold II of Tuscany also declares a new and liberal constitution in February to quell unrest, as does, unexpectedly, Pope Pius IX for the Papal States, and the French overthrow King Louis-Philippe Orléans and proclaim another republic. Even the long-powerful Austrian Foreign Minister Klemens von Metternich resigns his post in March as the Foreign Secretary and flees Vienna because of violent unrest across the Austrian Empire.

King Charles Albert of Sardinia is yet another monarch forced to grant a liberal constitution under duress because of rising pan-Italian nationalism, and those same pressures also push him, with Papal, Neapolitan and Tuscan support into invading the Austrian component kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia and take advantage of its rebellion against the Austrian Habsburgs. Initially successful in forcing the General Joseph Radetzky to retreat, the Papal, Neapolitan and Tuscan troops soon withdraw over fears that Sardinia is using the pan-Italian movement to its own ends. With the loss of those troops, French and British pressure is sufficient to make Charles Albert withdraw from Lombardy-Venetia and sign an armistice with Austria at Curtatone in May. Without that external focus of Italian nationalism to capture his citizens attention, he leaves the new constitution in place.

In Tuscany, however, further developments cause Leopold II to flee to Neapolitan Gaeta in March of 1849, joining Pius IX who had fled there three months previously and republics are declared in both their realms. Unlike Pius IX, Leopold II is generally well liked by his people and soon receives offers to return. First by counter-revolutionaries afraid of and wishing to prevent Austrian intervention, and later to be president of the new republic when it becomes clear that the Austrian forces remaining in Lombardy-Venetia cannot spare the troops after General Radetzky’s departure for Hungary. Pius IX eventually returns to Rome as well, his temporal power severely curtailed outside the Vatican demesnes, but not absent. The Vatican is given two deputies in parliament and finances the Roman Republic’s debt.

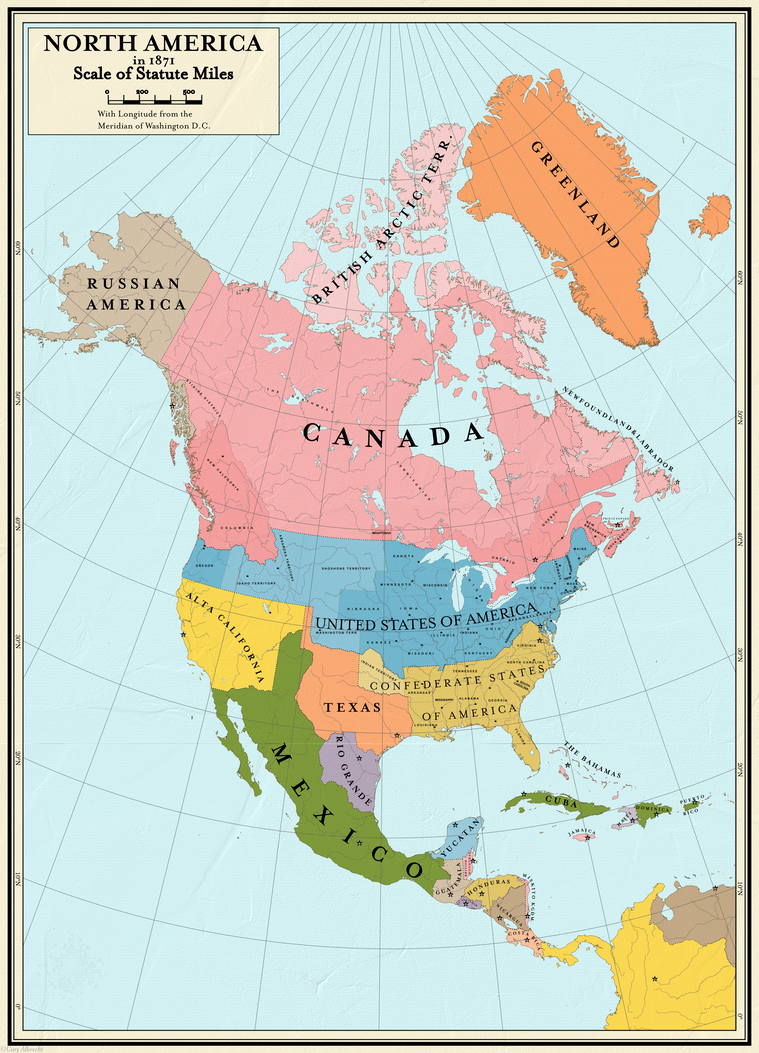

North in Denmark where uprisings were also underway and King Frederick VII joins the list of monarchs forced into granting liberal constitutions to their realms. Banking on the anti-interventionist policies the Concert of Europe has displayed, as well as the parallel rebellious distractions across Europe, he included the mostly German duchies of Holstein, Schleswig and Saxe-Lauenburg in the process, giving them separate but subordinate parliaments in union constitution to integrate them more firmly into the Danish realm while still giving the citizens expanded rights. Duke Christian August II of Augustenborg, also taking advantage of the 1848 uprisings, claims the dukedoms of Schleswig, Holstein and Saxe-Lauenburg. Because the three are largely populated by Germans and he himself is mostly German (though with links to the Danish Oldenburgs), Christian August tries to get Prussian support for the Holstein and Saxe-Lauenburg duchies to leave Denmark and become full members of German Confederation. Christian August is initially able to attract many pro-German sympathisers as well as Prussian help in the form of an army which enters Schleswig in April. However, after several losses to Danish forces Prussian troops are withdrawn from the three duchies. Prussia gives into to all Danish demands and signs the Treaty of Malmö in August of 1848. In the meantime, the petty nobility and bourgeoisie of the three duchies were starting to withdraw their support from Christian August after learning of the new Danish constitution and their own local parliaments which gave them expanded rights against the upper nobility like Christian August. As a result he drops his claims to the three duchies in return for being named heir presumptive to Frederick VII who is childless and believed to be infertile. With Tsar Nicholas I of Russia, as relative of the House of Oldenburg, insisting on the indissoluble union of the two dukedoms and the Danish crown, the Congress of London in January, 1849 accepts the Treaty of Malmö and the naming o Christian August II of Augustenborg as heir, but requires Denmark to join the German Zollverein. This is based in part on the precedent from Luxemburg and Limburg ten years previous and is supposedly to offset any economic losses that would arise from the new constitutions of Holstein and Saxe-Lauenburg, being subordinate to the Danish one, only nominally leaving them in the German Confederation. Frederick VII and the rest of the Danish nobility, however, see it as a chance for increased trade and a road to supremacy over their Swedish rivals. Seeing more of the trade from North America, Texian indigo-dyed cotton fabrics become popular among the Danish petty bourgeoisie and lower nobility.

In Austria, Kaiser Ferdinand I has insurrections throughout his empire and in April, 1848 the Hungarian Diet forces him to enact a set of reforms, granting them wide powers. However, even though the Hungarian Prime Minister, Batthyány, is a supporter of Hungary remaining in the Empire, the young Franz Joseph who becomes Kaiser after his uncle and father abdicate in quick succession revokes the new laws in August. As a result, Batthyány declares open revolution in September and hastily gathers an army. The Hungarians are defeated in October at Schwechat when they try to come to the aid of the rebellion in Vienna, but they are able to mostly hold their own inside Hungary to start. Their undoing, though, is two-fold. First, the Kingdom of Hungary is in some ways the Austrian Empire in miniature right down to the mistreated subordinate ethnic groups wanting to rebel, which Austria uses to its advantage. The second, is thanks to the British and French pressures on Sardinia, the Kaiser is able to call General Radetzky and part of his armies back from Italy in August. Because of the difficulties crossing the Alps, Radetzky marches through Trieste, Laibach and Agram and enters Hungary from the south in November, surprising the militarily inexperienced Hungarian head of state Lajos Kossuth who was having problems controlling his generals. By the time Kossuth cedes control to Artúr Görgey in June, 1849, it is too late. Though preventing Hungarian independence, Radetzky’s return is actually a good thing for Hungary in that Austria no longer need the Russian troops the new Foreign Minister Schwarzenberg was requesting from Tsar Nicholas I for. Letters between the two indicate that Nicholas would have sent 200,000 troops which would have annihilated the Hungarians, and many historians believe the repercussions would have been far worse than the so-called “12 Prisoners of Arad” and other possible reactions. As it is, while Radetzky’s military genius allows the 70,000 troops he brought from Northern Italy to decide things against the otherwise equally matched Austrian and Hungarian armies, Franz Joseph still has to accept many of the April Laws of the previous year when the treaty is signed at Világos in August by Görgey and Radetzky. The Hungarians, as the losers, have to accept the severing of Serbo-Croatian lands from the Lands of the Crown of St. Stephen, continued though lessened imperial taxation and subordination of the now permanent Hungarian Diet to the Imperial one.

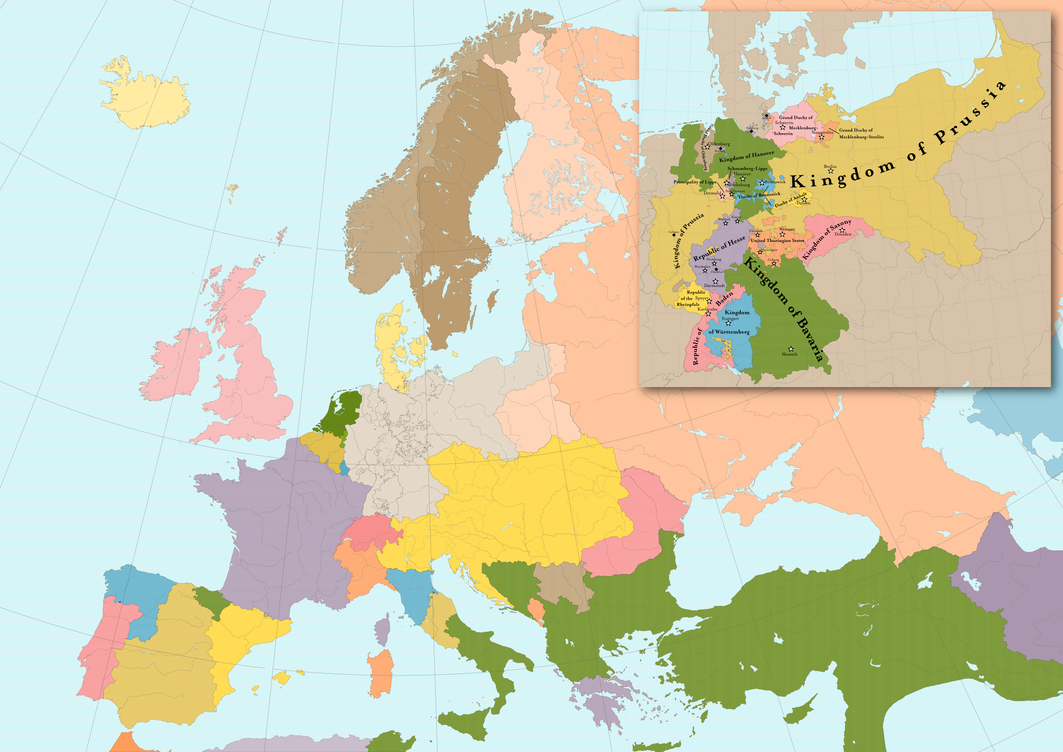

The Germanies were not free of strife either with everything from protests to outright armed insurrection breaking out in many of the states.. The Diet of the German Confederation is dissolved and the Frankfurt Parliament is called to creat a unifying constitution for a German Empire. It is populated by deputies from across the German Confederation but from the beginning is rife with the combination of regional politics, Austro-Prussian rivalries and moderate/radical dissension causing serious problems in talks to ostensibly unify the states. The Frankfurt Parliament ultimately fails and the constitution, without an emperor, it produces is only recognised the smaller states but not by Austria, Prussia, Bavaria, Hanover or Saxony.

In Baden, Bavaria’s Rhenish Palatinate exclave, and Saxony as a result of the failed Parliament, there are significant armed insurrections in the spring of 1849. While Baden’s and the Rhenish Palatinate’s rebellions are successful, the Saxon one was disorganised, being mostly students, and lacked weapons. In spite of not being able to receive Prussian assistance, the Saxon army was still able to crush the rebellion and continue the constitutional monarchy which had been in place since 1830. Because Austria’s own internal issues were under control, through not resolved, by this time, it stood with great Britain and France against Prussian assistance of local monarchs across the confederation under the guise that these were independent states and the Concert of Europe had a tradition of maintaining the balance of power by preventing such intervention as in Italy and Iberia. In reality, though, this was just another facet of the Austro-Prussian rivalry.

As a result, the new Republic of Baden and the Rheinland Republic are the only significant political changes in Central Europe, though the high emigration to the new countries in North and South America lessening the workforce population did what the Frankfurt Parliament could not - increase the pace of industrialisation and economic integration and thus favourable views of unification across Germanised Central Europe.

Not even France is immune to revolution, no matter how liberal King Louis-Philippe was compared to previous French monarchs, and in December the reconstituted French Republic elects Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte as president who is popular thanks to his support for the universal male suffrage now granted across the Republic.

Even though things are no longer violent, that doesn’t mean Europe itself had calmed down. Nationalist and democratic sympathies, as a result of the republican successes in Baden, France, the Rheinland, Rome and Tuscany, are often displayed in newspapers and heard in coffee houses and taverns across the continent. Many people desire or fear the changes they feel are coming.