You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

A House Divided: A TL

- Thread starter Utgard96

- Start date

Interesting. So Astoria becomes TTL's Seattle? A cup of Sloth Coffee please!

One-Eyed Willy's may or may not become one of the nation's favorite coffee chains ITTL.

Alex Richards

Donor

Interesting- Britain definitely gets the better end of the deal there in that territorial exchange.

RyanF

Banned

One-Eyed Willy's may or may not become one of the nation's favorite coffee chains ITTL.

You mean like that place a Geneva businessman is trying to set up in London?

Good start, and I say that as someone who has previously used the ridiculous Colombia River but US gets Olympic peninsula solution in a TL.

Now I'm interested; just don't abandon this...

I'm going to try my best, sadly I don't have the best track record on this but I've got a significant chunk of updates ready to go as a result of announcing prematurely. Updates should be forthcoming twice a week, on Tuesdays and Fridays, until that changes.

Interesting- Britain definitely gets the better end of the deal there in that territorial exchange.

Yes and no - certainly seeing it from the present day point of view, that's true, but we're at an early enough point in time that the Oregon Country was largely unsettled, unsurveyed Indian and fur trapper country. Plus the US had disproportionate amounts of national pride invested in the Maine question, which is why it took so long to resolve IOTL. From the point of view of the time, it's more debatable who got the upper hand, but New England is going to be quite pleased with the treaty.

I'm sorry about the lack of an update Tuesday last - I've been travelling and my Internet access was worse than I expected when I promised twice-weekly updates. Rest assured the pattern will continue from tomorrow.

#2: No Country for Literate Men

A House Divided #2: No Country for Literate Men

“May our country always be successful, but whether successful or otherwise, always right.”

***

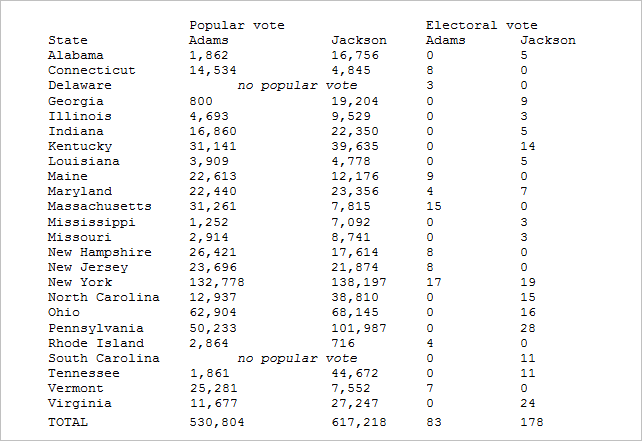

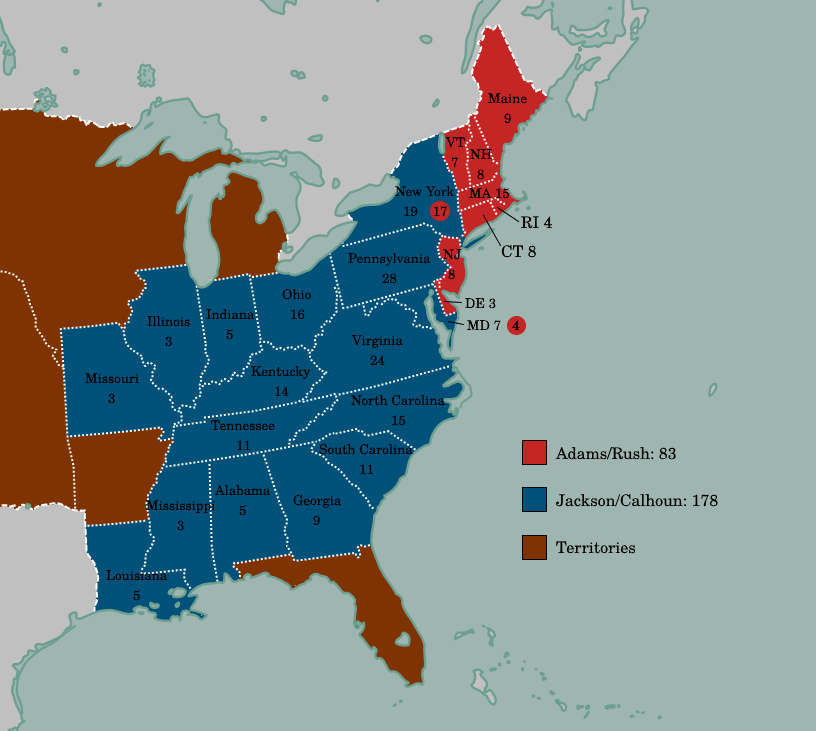

From “The Statistical Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections”

(c) 1992 by Horace Finkelstein (ed.)

New Orleans: Pelican Books

1828: The Rematch

The 1828 presidential election marked the start of a pattern that would continue in presidential politics until the Mexican War and the rise of the “Young Americans”. Incumbent President John Quincy Adams, a scion of one of Boston's oldest and most prominent political families (indeed, his own father had been President – see 1796), had served a controversial four years since the even more controversial 1824 election, and the belief that he and Henry Clay had conspired to steal the election lingered despite all evidence to the contrary. Andrew Jackson, the winner of the popular vote (though loser of the contingent vote) in 1824, had spent Adams' term building up support for a second run at the presidency, and from as early as 1825 (when the legislature of his home state of Tennessee passed a resolution nominating him for President) his candidacy was seen as a given. Adams, being the incumbent, was an equally obvious candidate, and though both men's supporters had congressional and electoral organisations (still unnamed by this point – the labels “Democratic” and “Republican” [1] would only arise in the 1830 midterm campaign), no formal nominations were actually carried out – the only time in post-Washington American history that this has occurred [2].

The campaign was extremely spirited, in contrast to most previous ones, and saw Adams supporters attack Jackson for being a barbaric illiterate unfit to govern the country, and Jackson supporters strike back against Adams for being an out-of-touch Massachusetts elite who was closer to the British than his own people. Undoubtedly they were helped in this by the signing of the Clay–Vaughan Treaty just a month before the election, which angered the West in particular for giving up rightful American soil – however, Maine hailed Adams as a national hero for successfully pushing their territorial claim. The other main achievement of the Adams administration, the Tariff of 1828, was opposed sternly by many Southern Jacksonians (notably incumbent Vice President and Jackson running mate John Calhoun), although Jackson himself ominously neglected to take a stand either way…

…The 1828 election was undoubtedly the most democratic ever held in the United States at the time. New York, Vermont, Georgia and Louisiana having moved from having electors chosen by their state legislatures to having them elected by general suffrage since 1824, only Delaware and South Carolina now neglected to hold direct presidential votes. And suffrage rights were expanding as well – the only states that retained absolute property qualifications for white men were Rhode Island, New Jersey and Tennessee, although several more states had harsher voting requirements for free blacks. Overall, some two million people had the vote in 1828, and of them, roughly three fifths turned out to vote for President – well over three times as many as had voted in 1824.

[3]

The result of the 1828 elections was relatively unsurprising – Adams' backing in the Northeast wasn't enough to save him, and on the back of strong support from the South and West, Andrew Jackson entered the White House as the first US President not born into wealth, and the first whose home state was neither Virginia nor Massachusetts… [4]

***

From “Waxhaws to White House: The Life and Times of Andrew Jackson”

(c) 1962 by Dr Josiah Harris

Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press

Jackson's inauguration was quite unlike that of any previous President. For the first time, the inaugural ceremony was held on the outside of the Capitol, on the East Portico, and the east lawn was filled with over twenty thousand eager spectators. Jackson, who had already entertained crowds of supporters along the three-week steamboat and carriage journey from Nashville to the capital, arrived on foot and entered the Capitol through a side door to avoid the crowd, before emerging on the portico, taking the inaugural oath administered by Chief Justice Marshall before giving his inaugural address. Although spectators describe the crowd as reverently silent throughout the speech, in this period before electric sound amplification, any attempts to pick up his words outside the immediate vicinity of the stairs would have been utterly in vain.

By the time Jackson was finished speaking, the crowd was beginning to break through the barrier placed on the Capitol stairs, and the President of the United States was forced to flee his own inauguration by running through the Capitol rotunda, mounting a horse readied for this purpose on the west lawn, and riding post-haste toward the White House. However, he would find scant calm there either. Seeing himself very much as a man of the people, Jackson had made a symbolic decision that his inaugural festivities should be open to everyone regardless of social status, and issued an invitation to the general public to visit the White House after the inauguration. A great many people had taken him up on his offer, and to the delight of many Republicans, the crowd quickly descended into a drunken mob that caused several thousand dollars of damage to the building, mostly in broken china. Jackson himself was forced to escape through a window and beat a hasty retreat across the Potomac to Alexandria, where he spent the night at Gadsby's Hotel… [5]

…In his inaugural address, Jackson had set out “the task of reform, which will require particularly the correction of those abuses that have brought the patronage of the Federal Government into conflict with the freedom of elections, and the counteraction of those causes which have disturbed the rightful course of appointment and have placed or continued power in unfaithful or incompetent hands” and added that he would “endeavor to select men whose diligence and talents will insure in their respective stations able and faithful cooperation, depending for the advancement of the public service more on the integrity and zeal of the public officers than on their numbers”. What this meant in practical terms was that Jackson tried to prevent institutional corruption by rotating officeholders and making sure no federal civil servant held any one position long enough to build a power base. Ironically, this intended anti-corruption measure, in giving rise to the tradition of presidential appointments to the federal civil service, did more than any other single act to give rise to the “spoils system” that characterized American political life for much of the 19th century...

***

From “A History of the Native Americans”

(c) 2001 by Arthur Lewis

Talikwa: Cherokee Publishers

In terms of his policy toward the Native nations, Andrew Jackson remains something of an enigma. It's highly likely that he held our kind in low regard – for evidence to this effect one need look no further than the Seminole War of 1818, when then-General Jackson exceeded orders to drive the Seminole out of U.S. Soil, massacring a large number of people and proceeding to invade Florida and create a diplomatic incident with Spain. Moreover, he made his opinion of Native culture fairly clear when, in an address to Congress in 1830, he asked “what good man would prefer a country covered with forests and ranged by a few thousand savages to our extensive Republic, studded with cities, towns, and prosperous farms, embellished with all the improvements which art can devise or industry execute, occupied by more than twelve million happy people, and filled with all the blessings of liberty, civilization, and religion?”

However, unlike many of his contemporaries, Jackson appears to have felt some degree of concern toward the impending doom of the Southeastern Native nations, for while President he championed not their extermination, but their relocation to lands west of the Mississippi – given the geography of the US at the time, this likely would've meant what is today the state of Cimarron – in the vainglorious hope that they might escape white violence there. In the spring of 1830, Senator White of Tennessee introduced legislation endorsed by Jackson that would've permitted the federal government to undertake such an expulsion, causing a long-drawn Congressional debate that hinged largely on the limits of federal authority…

…While the bill sailed through the Senate, over the objections of men like Frelinghuysen, the House of Representatives, which was more weighted toward the more populous northern states, was a different matter. There was great consternation in the House over the provisions of the bill, particularly the article that would've allowed the President to call up state militias to escort those natives who would move, with a strong implication that they might also be used to coerce those who would not [6]. This elicited strong opposition from the North in particular, and the bill ended up failing by a margin of two votes… [7]

…As feared by proponents of the Indian Removal Bill, its failure to pass resulted in the states taking matters into their own hands. In August of 1830, Governor Gabriel Moore of Alabama signed a law dividing the remaining Muscogee lands in his state up into counties and opening it to white settlement – when the Muscogee protested, their case was not heard, and when white settlers started moving in, hundreds if not thousands of Muscogee were massacred…

…Georgia attempted to push similar measures against the Cherokee, who occupied land Georgians felt important to connect their state to the burgeoning West, and to that effect issued legislation in 1828 depriving the Cherokee of their rights to autonomy in the state [8], clearly aiming to have them removed wholesale – however, the Cherokee were more adept at defending themselves than the Muscogee, and brought a case before the Supreme Court to indict Georgia for transgressing on their treaty rights. The Court declined to hear the case, citing their belief that the Cherokee were not a “foreign nation” and as such could not sue a state in a direct sense, but reserved itself by stating that “in a case with proper parties”, it might be sympathetic to the Cherokee's case. Such a case would not appear until 1832, when a missionary by the name of Samuel Worcester sued the State of Georgia for its law that forbade any non-native from entering native lands without permission from the state. Chief Justice Marshall, supported by five out of six associate justices then on the bench, ruled that this was a violation of tribal sovereignty, and that no individual state had the authority to make rulings over Native nations. However, for all that this appeared to be a victory, the Court had no way to enforce it in practice, and repression against the Cherokee would continue for several years…

***

[1] The Republicans are largely the OTL Whigs, though their membership is somewhat different from OTL. See future updates.

[2] It's true that the 1824 election was largely fought on a nonpartisan basis, but the Democratic-Republican Party did hold a nominating caucus, which was sparsely attended and ended up nominating William Crawford, who came third and was promptly trounced at the contingent election.

[3] The changes from OTL here are mostly cosmetic – Adams gains slightly in the Northeast while Jackson gains slightly elsewhere – but because the states pushed toward Adams are largely bigger, this means Adams actually gains almost thirty thousand votes. The only state that actually flips as a result of this is Maryland, but since they chose electors by district rather than statewide, this means only three of the state's eleven electors change allegiance, and three electors flipping the other way in New York and Maine means that the electoral vote divides exactly as IOTL.

[4] Obviously this is also true of OTL – it would also be entirely legitimate to say Jackson was the first president to neither be a Virginian nor have the surname “Adams”.

[5] This all happened IOTL. You can imagine the contrast against Adams' inauguration, which took place inside the House of Representatives and was followed by a relatively low-key ball for federal employees and the DC social register.

[6] This was implicit in the OTL Indian Removal Act, but here it's explicitly stated.

[7] IOTL, the bill passed 101-97, with 11 members abstaining. ITTL, a few more northern members who abstained IOTL were persuaded to side against the bill, and the split is 100-102.

[8] This legislation predates the PoD.

“May our country always be successful, but whether successful or otherwise, always right.”

***

From “The Statistical Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections”

(c) 1992 by Horace Finkelstein (ed.)

New Orleans: Pelican Books

1828: The Rematch

The 1828 presidential election marked the start of a pattern that would continue in presidential politics until the Mexican War and the rise of the “Young Americans”. Incumbent President John Quincy Adams, a scion of one of Boston's oldest and most prominent political families (indeed, his own father had been President – see 1796), had served a controversial four years since the even more controversial 1824 election, and the belief that he and Henry Clay had conspired to steal the election lingered despite all evidence to the contrary. Andrew Jackson, the winner of the popular vote (though loser of the contingent vote) in 1824, had spent Adams' term building up support for a second run at the presidency, and from as early as 1825 (when the legislature of his home state of Tennessee passed a resolution nominating him for President) his candidacy was seen as a given. Adams, being the incumbent, was an equally obvious candidate, and though both men's supporters had congressional and electoral organisations (still unnamed by this point – the labels “Democratic” and “Republican” [1] would only arise in the 1830 midterm campaign), no formal nominations were actually carried out – the only time in post-Washington American history that this has occurred [2].

The campaign was extremely spirited, in contrast to most previous ones, and saw Adams supporters attack Jackson for being a barbaric illiterate unfit to govern the country, and Jackson supporters strike back against Adams for being an out-of-touch Massachusetts elite who was closer to the British than his own people. Undoubtedly they were helped in this by the signing of the Clay–Vaughan Treaty just a month before the election, which angered the West in particular for giving up rightful American soil – however, Maine hailed Adams as a national hero for successfully pushing their territorial claim. The other main achievement of the Adams administration, the Tariff of 1828, was opposed sternly by many Southern Jacksonians (notably incumbent Vice President and Jackson running mate John Calhoun), although Jackson himself ominously neglected to take a stand either way…

…The 1828 election was undoubtedly the most democratic ever held in the United States at the time. New York, Vermont, Georgia and Louisiana having moved from having electors chosen by their state legislatures to having them elected by general suffrage since 1824, only Delaware and South Carolina now neglected to hold direct presidential votes. And suffrage rights were expanding as well – the only states that retained absolute property qualifications for white men were Rhode Island, New Jersey and Tennessee, although several more states had harsher voting requirements for free blacks. Overall, some two million people had the vote in 1828, and of them, roughly three fifths turned out to vote for President – well over three times as many as had voted in 1824.

[3]

The result of the 1828 elections was relatively unsurprising – Adams' backing in the Northeast wasn't enough to save him, and on the back of strong support from the South and West, Andrew Jackson entered the White House as the first US President not born into wealth, and the first whose home state was neither Virginia nor Massachusetts… [4]

***

From “Waxhaws to White House: The Life and Times of Andrew Jackson”

(c) 1962 by Dr Josiah Harris

Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press

Jackson's inauguration was quite unlike that of any previous President. For the first time, the inaugural ceremony was held on the outside of the Capitol, on the East Portico, and the east lawn was filled with over twenty thousand eager spectators. Jackson, who had already entertained crowds of supporters along the three-week steamboat and carriage journey from Nashville to the capital, arrived on foot and entered the Capitol through a side door to avoid the crowd, before emerging on the portico, taking the inaugural oath administered by Chief Justice Marshall before giving his inaugural address. Although spectators describe the crowd as reverently silent throughout the speech, in this period before electric sound amplification, any attempts to pick up his words outside the immediate vicinity of the stairs would have been utterly in vain.

By the time Jackson was finished speaking, the crowd was beginning to break through the barrier placed on the Capitol stairs, and the President of the United States was forced to flee his own inauguration by running through the Capitol rotunda, mounting a horse readied for this purpose on the west lawn, and riding post-haste toward the White House. However, he would find scant calm there either. Seeing himself very much as a man of the people, Jackson had made a symbolic decision that his inaugural festivities should be open to everyone regardless of social status, and issued an invitation to the general public to visit the White House after the inauguration. A great many people had taken him up on his offer, and to the delight of many Republicans, the crowd quickly descended into a drunken mob that caused several thousand dollars of damage to the building, mostly in broken china. Jackson himself was forced to escape through a window and beat a hasty retreat across the Potomac to Alexandria, where he spent the night at Gadsby's Hotel… [5]

…In his inaugural address, Jackson had set out “the task of reform, which will require particularly the correction of those abuses that have brought the patronage of the Federal Government into conflict with the freedom of elections, and the counteraction of those causes which have disturbed the rightful course of appointment and have placed or continued power in unfaithful or incompetent hands” and added that he would “endeavor to select men whose diligence and talents will insure in their respective stations able and faithful cooperation, depending for the advancement of the public service more on the integrity and zeal of the public officers than on their numbers”. What this meant in practical terms was that Jackson tried to prevent institutional corruption by rotating officeholders and making sure no federal civil servant held any one position long enough to build a power base. Ironically, this intended anti-corruption measure, in giving rise to the tradition of presidential appointments to the federal civil service, did more than any other single act to give rise to the “spoils system” that characterized American political life for much of the 19th century...

***

From “A History of the Native Americans”

(c) 2001 by Arthur Lewis

Talikwa: Cherokee Publishers

In terms of his policy toward the Native nations, Andrew Jackson remains something of an enigma. It's highly likely that he held our kind in low regard – for evidence to this effect one need look no further than the Seminole War of 1818, when then-General Jackson exceeded orders to drive the Seminole out of U.S. Soil, massacring a large number of people and proceeding to invade Florida and create a diplomatic incident with Spain. Moreover, he made his opinion of Native culture fairly clear when, in an address to Congress in 1830, he asked “what good man would prefer a country covered with forests and ranged by a few thousand savages to our extensive Republic, studded with cities, towns, and prosperous farms, embellished with all the improvements which art can devise or industry execute, occupied by more than twelve million happy people, and filled with all the blessings of liberty, civilization, and religion?”

However, unlike many of his contemporaries, Jackson appears to have felt some degree of concern toward the impending doom of the Southeastern Native nations, for while President he championed not their extermination, but their relocation to lands west of the Mississippi – given the geography of the US at the time, this likely would've meant what is today the state of Cimarron – in the vainglorious hope that they might escape white violence there. In the spring of 1830, Senator White of Tennessee introduced legislation endorsed by Jackson that would've permitted the federal government to undertake such an expulsion, causing a long-drawn Congressional debate that hinged largely on the limits of federal authority…

…While the bill sailed through the Senate, over the objections of men like Frelinghuysen, the House of Representatives, which was more weighted toward the more populous northern states, was a different matter. There was great consternation in the House over the provisions of the bill, particularly the article that would've allowed the President to call up state militias to escort those natives who would move, with a strong implication that they might also be used to coerce those who would not [6]. This elicited strong opposition from the North in particular, and the bill ended up failing by a margin of two votes… [7]

…As feared by proponents of the Indian Removal Bill, its failure to pass resulted in the states taking matters into their own hands. In August of 1830, Governor Gabriel Moore of Alabama signed a law dividing the remaining Muscogee lands in his state up into counties and opening it to white settlement – when the Muscogee protested, their case was not heard, and when white settlers started moving in, hundreds if not thousands of Muscogee were massacred…

…Georgia attempted to push similar measures against the Cherokee, who occupied land Georgians felt important to connect their state to the burgeoning West, and to that effect issued legislation in 1828 depriving the Cherokee of their rights to autonomy in the state [8], clearly aiming to have them removed wholesale – however, the Cherokee were more adept at defending themselves than the Muscogee, and brought a case before the Supreme Court to indict Georgia for transgressing on their treaty rights. The Court declined to hear the case, citing their belief that the Cherokee were not a “foreign nation” and as such could not sue a state in a direct sense, but reserved itself by stating that “in a case with proper parties”, it might be sympathetic to the Cherokee's case. Such a case would not appear until 1832, when a missionary by the name of Samuel Worcester sued the State of Georgia for its law that forbade any non-native from entering native lands without permission from the state. Chief Justice Marshall, supported by five out of six associate justices then on the bench, ruled that this was a violation of tribal sovereignty, and that no individual state had the authority to make rulings over Native nations. However, for all that this appeared to be a victory, the Court had no way to enforce it in practice, and repression against the Cherokee would continue for several years…

***

[1] The Republicans are largely the OTL Whigs, though their membership is somewhat different from OTL. See future updates.

[2] It's true that the 1824 election was largely fought on a nonpartisan basis, but the Democratic-Republican Party did hold a nominating caucus, which was sparsely attended and ended up nominating William Crawford, who came third and was promptly trounced at the contingent election.

[3] The changes from OTL here are mostly cosmetic – Adams gains slightly in the Northeast while Jackson gains slightly elsewhere – but because the states pushed toward Adams are largely bigger, this means Adams actually gains almost thirty thousand votes. The only state that actually flips as a result of this is Maryland, but since they chose electors by district rather than statewide, this means only three of the state's eleven electors change allegiance, and three electors flipping the other way in New York and Maine means that the electoral vote divides exactly as IOTL.

[4] Obviously this is also true of OTL – it would also be entirely legitimate to say Jackson was the first president to neither be a Virginian nor have the surname “Adams”.

[5] This all happened IOTL. You can imagine the contrast against Adams' inauguration, which took place inside the House of Representatives and was followed by a relatively low-key ball for federal employees and the DC social register.

[6] This was implicit in the OTL Indian Removal Act, but here it's explicitly stated.

[7] IOTL, the bill passed 101-97, with 11 members abstaining. ITTL, a few more northern members who abstained IOTL were persuaded to side against the bill, and the split is 100-102.

[8] This legislation predates the PoD.

Last edited:

From a quick glance, Missouri, Maryland and Georgia stand out in the election results compared to OTL. An artifact of randomization or something underlying beyond my knowledge?

The former, mostly.

#3: South of the Border

A House Divided #3: South of the Border

“America is ungovernable; all those who served the revolution have plowed the sea.”

***

From “Mexico Between the Wars, 1820-1850”

(c) 1976 by Manuel Guzmán

Monterrey: University of New Leon Press

When Mexico's independence was finally secured, it was only through the defection of much of the Spanish troops in the country, whose commander Agustín de Iturbide had far from the best relations with the mainland and – along with most of the criollo class – was beginning to lose confidence in Spanish rule. Iturbide joined forces with rebel leader Vicente Guerrero to formulate the Plan of Iguala, also known as the ”Plan of the Three Guarantees” for its main points – the signatories would fight for independence (a Mexico free from Spanish rule), unity (an end to the caste system that had dominated Mexican society up until then), and crucially, religion (the preservation of Roman Catholicism as the sole religion of Mexico). This plan managed to unite most of Mexico behind it, and Iturbide and Guerrero were able to raise an army of some 17,000 men…

…The viceroy of New Spain, Juan de O'Donojú [1], was of a liberal persuasion, and had been appointed by a liberal government in Madrid to oversee a transition to greater Mexican autonomy; when faced with an armed revolt, however, he eventually conceded independence to Mexico. The Treaty of Córdoba, signed in August of 1821, saw Spain relinquish sovereignty to a monarchist Mexican state, whose crown would be offered first to King Ferdinand VII of Spain and then to his brothers in order of seniority should the King refuse.

Ferdinand VII was decidedly not a liberal or a Mexican independence sympathizer, and not only did he reject the crown, he declared the treaty invalid and refused to recognize Mexico's independence. Nonetheless, with the adoption of the Declaration of Independence a little over a month after the treaty's signing, supported by all sides of Mexican society, independence was more or less a fait accompli. Any hope of getting a European monarch was exhausted when King Ferdinand presented credible plans to reconquer Mexico; the Spanish monarchy may have lost much of its power by this time, but the princely houses of Europe were still loath to cross them so visibly. So it was that a junta was set up to govern Mexico on a provisional basis until an emperor could be found; this was presided over by Iturbide, who was soon floated as a potential monarch…

…On May 18, 1822, the Regiment of Celaya led a mass demonstration outside Iturbide's residence in Mexico City, demanding he take the throne ”for the good of the nation”. Iturbide appeared before the crowd and repeatedly insisted that he did not want to be emperor, however, he cannot have been terribly sincere this time around, for the very next day the Congress unanimously invited him to take the throne, and he accepted. There has been much debate over whether Congress made this invitation under duress, as Mexico City saw a significant amount of tension instigated by the Regiment of Celaya and other pro-Iturbide groups; generally speaking, liberal historians have portrayed Iturbide's ascension as him staging demonstrations in support of himself and then manoeuvering Congress to ”invite” him to take power, while conservative historians have taken the view that he was legitimately popular for his efforts in securing independence and that Congress willingly and enthusiastically elevated him to the monarchy. However this may have been, Iturbide was now in power, and Mexico appeared for the time being to have some stability…

…While eventually supportive of independence, Iturbide cannot be called a liberal by any means, and as he entrenched himself in power this became strikingly obvious. His ascension was backed by the clergy and the landed classes, but Congress was dominated by liberals, many of whom were of republican persuasions, and while in theory it gathered to draft a constitution, in practice it produced no such draft in the eight months it sat, and mainly issued statements of protest against Iturbide's rule. The situation came to a head in October of 1822, when rumors circulated of a plot against the Emperor by several members of Congress; Iturbide seized the opportunity to declare the body as a whole guilty of treason, and to dissolve it indefinitely…

…With the signing of the Plan of Casa Mata, the Mexican Empire's fate was sealed; nearly all the provinces supported the Plan, and Santa Anna was able to raise an army to march on Mexico City in support of it. With Iturbide unable to pay his soldiers [2], very little in the way of resistance was put up, and in early March he summoned Congress back to the capital. On March 19, he presented his abdication to the legislature, and the executive power was handed over to a new junta composed of Nicolás Bravo, Guadalupe Victoria and Pedro Celestino Negrete. The Mexican Empire was dead, and the Mexican Republic born.

The First Republic

…The government junta sat for some eighteen months, until the new Congress announced terms for a presidential election to be held in October of 1824. A federalist model inspired by the United States was agreed upon, whereby each state legislature would nominate two candidates for President, and whoever got the most nominations would win, with the runner-up becoming Vice President. Thirty states nominated Guadelupe Victoria, putting him first ahead of Nicolás Bravo, and the two became the first President and Vice President of Mexico…

…President Victoria wasted no time in taking up the task of economic reconstruction, badly needed after fifteen years of war. He created the first unified Mexican merchant marine in 1825, to alleviate the poor supply situation caused by Spain's continued refusal to recognize Mexico's independence. In addition, he secured loans from British banks to cover up the budget shortfall caused by war recovery. The abolition of slavery, long promised as part of independence, was declared in September of 1825; in the same year, however, Victoria had signed into law a highly favorable colonization law, which gave foreign nationals who settled Mexico's northern territories the right to claim land and hold it tax-exempt for a period of ten years. Enticed by this, a steady stream of Americans began to cross the border into Tejas (as it then was), and most of them openly flaunted the ban on slavery and brought slave-based plantation agriculture with them. Moreover, several of the American empresarios contracted by the Mexican government to find settlers more or less openly refused to recognize Mexican sovereignty over their land; one of them, Haden Edwards, went so far as to rebel in December of 1826, forming the ”Republic of Fredonia” around Nacogdoches in east Texas, which was put down by Mexican troops within a month.

Meanwhile on the homefront, conflict was rising between the different factions in Mexico City, symbolized by the two dominant Masonic lodges: the Scottish Rite, whose members were politically moderate and had hitherto dominated political life, and the York Rite, whose members were generally of a more radical persuasion. For want of formal political parties, these groups formed the main political organization in Mexico at this time [3], and their members were at constant loggerheads. Vice President Bravo, a member of the Scottish Rite, grew more and more fearful that his influence was shrinking, and in December of 1827 he issued a pronunciamiento calling for the abolition of secret societies and the expulsion of American minister Joel Roberts Poinsett, who was thought to pose an undue influence over the York Rite. Bravo's rebellion was very quickly defeated by federal troops under Vicente Guerrero, and its ringleaders imprisoned, apart from Bravo himself, who was exiled…

…In the autumn of 1828, presidential elections were held to replace Victoria, who had communicated his desire to step down upon completion of his four-year term in April of 1829. The main two candidates were Vicente Guerrero, nominated by backers of the Scottish Rite, and Manuel Gómez Pedraza, who was nominated by backers of the York Rite and supported by President Victoria. Guerrero's supporters, who included several other prominent army commanders, were enraged by Victoria's backing of Gómez Pedraza, and are reputed to have threatened a revolt to install Guerrero as president by force; however, the rebellion proved unable to gather traction, and Victoria was eventually able to kill it in its cradle by calling out the Mexico City garrison and issuing a proclamation to the effect that “the task of the President is to defend the Constitution and the democratic process, and in particular to defend them against those who would impose their will on the nation by force of arms”. Gómez Pedraza was eventually able to gather the support of enough states to win election, and took office in 1829, but his presidency would not be without controversy… [4]

***

From “The Liberator: The Life of Simón Bolívar”

(c) 1985 by Adolfo Hernández

Translation (c) 1988 by Luis Castillo

Caracas: Ediciones Quirós

Bolívar returned from Peru in early 1827 to find Colombia in a state of chaos. Both in Venezuela and in Quito [OTL Ecuador] there were open revolts in progress, the latter against the government's free-trade policies, which were beneficial to agriculture in Venezuela and New Granada but damaging to the proto-industrial Quito economy. The Venezuelan revolt was a more straightforward federalist revolt against what was perceived as the overbearing central authority of Bogotá, similar to innumerable other such movements in early independent Latin America. The federalist viewpoint held significant sympathy in New Granada and Quito as well, with Vice President (and acting President during Bolívar's absence from Colombia) Francisco de Paula Santander among its chief advocates. However, it was strongest in Venezuela, where José Antonio Páez, the Military Governor of Caracas, had led the La Cosiata rebellion [5] in 1826 against the central government (…) Páez was unwilling to recognize Santander's rule over Venezuela, but when Bolívar himself returned to power, Páez agreed to end the revolt in exchange for retaining his position as governor…

…Having re-established his authority in Bogotá, Bolívar decided that since the existing state of affairs was clearly untenable, a second constitutional convention should be held to amend the Cúcuta constitution and provide a new settlement that would make Colombia governable. The convention was called to Ocaña, assembling in April of 1828, and conflict immediately broke out between federalists and centralists. Bolívar wanted to use the convention to push for his ideal form of government, as expressed in the Bolivian constitution of 1826 [6], believing that this would bring stability to the country's government and allow him to take control over the separatist regions [7]. However, this sentiment was opposed by the majority of the delegates, notably Vice President Santander as well as nearly every single provincial leader, who argued that the size of the country and the poor state of communications would make the country ungovernable from a central location. Bolívar's determination and stubbornness was the main thing preventing the federalists from imposing their will on the convention, and with the president of the nation shoring up the minority side with all the ferocity that had driven the Spanish out of most of a continent, the convention remained deadlocked for weeks.

Then, on May 15th, something unexpected happened. During a negotiation session, Bolívar suddenly slumped down in his seat, his head banging against the table, and remained still for several minutes as the room went into a blind panic. The nearest physician was sent for, and took the Liberator into a separate room where a bed was set up. A quick examination appeared to confirm that Bolívar had suffered a severe heart attack, and that with the relatively spartan medical resources in the provincial town, it appeared likely that this would be his deathbed…

…In the end, as feared, the physicians of Ocaña proved unable to save the Liberator. He spent the following day on his deathbed going in and out of consciousness, during which time he saw Santander and several other leading figures of the convention. He did not, of course, have any close relatives who could be summoned, but his mistress Manuela Sáenz was by his side throughout. His final words were spoken to her, minutes before slipping back into unconsciousness, and have been lost to history; we do, however, know what the last thing he told Santander was, because the latter used the words in his address to the convention on the 17th – “Keep the nation together, keep the revolution alive” – although we obviously have no way of knowing whether this was actually true or if Santander fabricated the statement for dramatic effect… [8]

…The convention assembled hastily on the following day, and with little debate, agreed to proclaim Santander as the new President of Colombia for two years, with regular elections to be held in July of 1830. The federalists now decisively held the upper hand, and the convention could soon agree on a new constitution, which was in effect mainly an amendment of the Cúcuta constitution. The main change was that the departments would be significantly more autonomous, with the intendants abolished in favor of governors elected by the assemblies of their department [9]. Otherwise most of the provisions remained in place, and the twelve existing departments [10] would remain in place for the foreseeable future…

***

From “Colombia: The Early Years”

(c) 1988 by Garrison Fernandez

Philadelphia: United Press

…By the time Santander replaced the departed Bolívar as chief executive, the situation, although less troublesome than previously, remained precarious. The regional revolts had simmered down for the time being, but as long as the war against Spain continued to rage, the economic situation would mean continued unrest. Fortunately for Santander and for Colombia, the situation in Spain would soon change. The overthrow of Charles X of France in July of 1830 meant that Ferdinand VII had lost his most important foreign ally, thus weakening his position considerably. Implored by his advisors not to overextend his empire, King Ferdinand decided to shift focus to consolidating the remainder of it. To this end, a ceasefire – not a formal peace, nor formal Spanish recognition of independence – was offered to Colombia, and President Santander accepted it wholeheartedly. The nation was at peace, and the crisis appeared over. Colombia appeared to be on the path to stability…

***

[1] A large number of Irish Catholics took up service under the Spanish crown; O'Donojú's ancestor was one of them, but he himself was a Spaniard by birth.

[2] I've skipped over a significant part of Iturbide's rule, including when the gradually worsening economic situation got to the point where he was unable to pay his men.

[3] Not making this up, early Mexican politics were quite literally run by warring groups of Freemasons. The more I read into this the more I'm convinced that the Anti-Masonic Party was on to something.

[4] IOTL, the army did launch a rebellion in support of Guerrero's candidacy, and eventually got Gómez Pedraza to concede the election, starting a long tradition of military interference in presidential politics which would result in no president between Victoria and José Joaquín de Herrera (1848-51) completing a full term in office. ITTL, with the peaceful transfer of power between Victoria and Gómez Pedraza, this is somewhat nipped in the bud, although I wouldn't be able to change the nature of Mexican politics enough to stop the army being a factor altogether without a much earlier PoD.

[5] Cosiata is a local Spanish colloquialism meaning something like “thingamajig” (or so I'm told).

[6] This was a rather weird form of quasi-republican parliamentary government, inspired by what Bolívar saw as the most stable democracies thus far created, namely ancient Rome and Great Britain. The system would've had a President appointed for life and able to choose his successor, with very limited powers except over national defense and overseeing the other executive officials. Power would instead be vested in a tricameral parliament, consisting of an elected Chamber of Tribunes who would hold power over matters of fiscal policy and have the sole right to declare war, a hereditary Senate appointed by the President who would oversee the judiciary and appoint regional officials, and a body of Censors who would act as a check on the other two houses' power in the name of the people – Bolívar was unclear on how these would be selected, but their neutrality would've been essential to the operation of government. Naturally, the book covers this system during its chapter on the Bolivian constitutional convention, which is why I need to explain it in a footnote here.

[7] Bolívar was, to say the least, a bit of a control freak.

[8] IOTL, Bolívar's health was in decline at this point, but he survived until the end of the convention, which would've produced a federalist constitution had he not ordered his supporters to withdraw from it, leading to its disbandment. He subsequently tried to push his centralist agenda through regardless, but was frustrated at every turn, and resigned in April of 1830, intending to go into self-imposed exile in Europe. However, he died in Cartagena before he could set sail.

[9] The Cúcuta constitution (which predates the PoD) provided for most federal offices to be elected indirectly by an assembly of electors in each province, who were elected by voters in each canton (a level between the province and parish). The departments, which consisted of several provinces each, were to be governed by intendants appointed by the President; here that provision is replaced.

[10] One department (Istmo) corresponding to OTL Panama, three (Ecuador, Guayaquil and Azuay) corresponding to OTL Ecuador, and four each corresponding to OTL Colombia (Boyacá, Cauca, Cundinamarca and Magdalena) and Venezuela (Maturín, Orinoco, Venezuela and Zulia).

“America is ungovernable; all those who served the revolution have plowed the sea.”

***

From “Mexico Between the Wars, 1820-1850”

(c) 1976 by Manuel Guzmán

Monterrey: University of New Leon Press

The Empire

When Mexico's independence was finally secured, it was only through the defection of much of the Spanish troops in the country, whose commander Agustín de Iturbide had far from the best relations with the mainland and – along with most of the criollo class – was beginning to lose confidence in Spanish rule. Iturbide joined forces with rebel leader Vicente Guerrero to formulate the Plan of Iguala, also known as the ”Plan of the Three Guarantees” for its main points – the signatories would fight for independence (a Mexico free from Spanish rule), unity (an end to the caste system that had dominated Mexican society up until then), and crucially, religion (the preservation of Roman Catholicism as the sole religion of Mexico). This plan managed to unite most of Mexico behind it, and Iturbide and Guerrero were able to raise an army of some 17,000 men…

…The viceroy of New Spain, Juan de O'Donojú [1], was of a liberal persuasion, and had been appointed by a liberal government in Madrid to oversee a transition to greater Mexican autonomy; when faced with an armed revolt, however, he eventually conceded independence to Mexico. The Treaty of Córdoba, signed in August of 1821, saw Spain relinquish sovereignty to a monarchist Mexican state, whose crown would be offered first to King Ferdinand VII of Spain and then to his brothers in order of seniority should the King refuse.

Ferdinand VII was decidedly not a liberal or a Mexican independence sympathizer, and not only did he reject the crown, he declared the treaty invalid and refused to recognize Mexico's independence. Nonetheless, with the adoption of the Declaration of Independence a little over a month after the treaty's signing, supported by all sides of Mexican society, independence was more or less a fait accompli. Any hope of getting a European monarch was exhausted when King Ferdinand presented credible plans to reconquer Mexico; the Spanish monarchy may have lost much of its power by this time, but the princely houses of Europe were still loath to cross them so visibly. So it was that a junta was set up to govern Mexico on a provisional basis until an emperor could be found; this was presided over by Iturbide, who was soon floated as a potential monarch…

…On May 18, 1822, the Regiment of Celaya led a mass demonstration outside Iturbide's residence in Mexico City, demanding he take the throne ”for the good of the nation”. Iturbide appeared before the crowd and repeatedly insisted that he did not want to be emperor, however, he cannot have been terribly sincere this time around, for the very next day the Congress unanimously invited him to take the throne, and he accepted. There has been much debate over whether Congress made this invitation under duress, as Mexico City saw a significant amount of tension instigated by the Regiment of Celaya and other pro-Iturbide groups; generally speaking, liberal historians have portrayed Iturbide's ascension as him staging demonstrations in support of himself and then manoeuvering Congress to ”invite” him to take power, while conservative historians have taken the view that he was legitimately popular for his efforts in securing independence and that Congress willingly and enthusiastically elevated him to the monarchy. However this may have been, Iturbide was now in power, and Mexico appeared for the time being to have some stability…

…While eventually supportive of independence, Iturbide cannot be called a liberal by any means, and as he entrenched himself in power this became strikingly obvious. His ascension was backed by the clergy and the landed classes, but Congress was dominated by liberals, many of whom were of republican persuasions, and while in theory it gathered to draft a constitution, in practice it produced no such draft in the eight months it sat, and mainly issued statements of protest against Iturbide's rule. The situation came to a head in October of 1822, when rumors circulated of a plot against the Emperor by several members of Congress; Iturbide seized the opportunity to declare the body as a whole guilty of treason, and to dissolve it indefinitely…

…With the signing of the Plan of Casa Mata, the Mexican Empire's fate was sealed; nearly all the provinces supported the Plan, and Santa Anna was able to raise an army to march on Mexico City in support of it. With Iturbide unable to pay his soldiers [2], very little in the way of resistance was put up, and in early March he summoned Congress back to the capital. On March 19, he presented his abdication to the legislature, and the executive power was handed over to a new junta composed of Nicolás Bravo, Guadalupe Victoria and Pedro Celestino Negrete. The Mexican Empire was dead, and the Mexican Republic born.

The First Republic

…The government junta sat for some eighteen months, until the new Congress announced terms for a presidential election to be held in October of 1824. A federalist model inspired by the United States was agreed upon, whereby each state legislature would nominate two candidates for President, and whoever got the most nominations would win, with the runner-up becoming Vice President. Thirty states nominated Guadelupe Victoria, putting him first ahead of Nicolás Bravo, and the two became the first President and Vice President of Mexico…

…President Victoria wasted no time in taking up the task of economic reconstruction, badly needed after fifteen years of war. He created the first unified Mexican merchant marine in 1825, to alleviate the poor supply situation caused by Spain's continued refusal to recognize Mexico's independence. In addition, he secured loans from British banks to cover up the budget shortfall caused by war recovery. The abolition of slavery, long promised as part of independence, was declared in September of 1825; in the same year, however, Victoria had signed into law a highly favorable colonization law, which gave foreign nationals who settled Mexico's northern territories the right to claim land and hold it tax-exempt for a period of ten years. Enticed by this, a steady stream of Americans began to cross the border into Tejas (as it then was), and most of them openly flaunted the ban on slavery and brought slave-based plantation agriculture with them. Moreover, several of the American empresarios contracted by the Mexican government to find settlers more or less openly refused to recognize Mexican sovereignty over their land; one of them, Haden Edwards, went so far as to rebel in December of 1826, forming the ”Republic of Fredonia” around Nacogdoches in east Texas, which was put down by Mexican troops within a month.

Meanwhile on the homefront, conflict was rising between the different factions in Mexico City, symbolized by the two dominant Masonic lodges: the Scottish Rite, whose members were politically moderate and had hitherto dominated political life, and the York Rite, whose members were generally of a more radical persuasion. For want of formal political parties, these groups formed the main political organization in Mexico at this time [3], and their members were at constant loggerheads. Vice President Bravo, a member of the Scottish Rite, grew more and more fearful that his influence was shrinking, and in December of 1827 he issued a pronunciamiento calling for the abolition of secret societies and the expulsion of American minister Joel Roberts Poinsett, who was thought to pose an undue influence over the York Rite. Bravo's rebellion was very quickly defeated by federal troops under Vicente Guerrero, and its ringleaders imprisoned, apart from Bravo himself, who was exiled…

…In the autumn of 1828, presidential elections were held to replace Victoria, who had communicated his desire to step down upon completion of his four-year term in April of 1829. The main two candidates were Vicente Guerrero, nominated by backers of the Scottish Rite, and Manuel Gómez Pedraza, who was nominated by backers of the York Rite and supported by President Victoria. Guerrero's supporters, who included several other prominent army commanders, were enraged by Victoria's backing of Gómez Pedraza, and are reputed to have threatened a revolt to install Guerrero as president by force; however, the rebellion proved unable to gather traction, and Victoria was eventually able to kill it in its cradle by calling out the Mexico City garrison and issuing a proclamation to the effect that “the task of the President is to defend the Constitution and the democratic process, and in particular to defend them against those who would impose their will on the nation by force of arms”. Gómez Pedraza was eventually able to gather the support of enough states to win election, and took office in 1829, but his presidency would not be without controversy… [4]

***

From “The Liberator: The Life of Simón Bolívar”

(c) 1985 by Adolfo Hernández

Translation (c) 1988 by Luis Castillo

Caracas: Ediciones Quirós

Bolívar returned from Peru in early 1827 to find Colombia in a state of chaos. Both in Venezuela and in Quito [OTL Ecuador] there were open revolts in progress, the latter against the government's free-trade policies, which were beneficial to agriculture in Venezuela and New Granada but damaging to the proto-industrial Quito economy. The Venezuelan revolt was a more straightforward federalist revolt against what was perceived as the overbearing central authority of Bogotá, similar to innumerable other such movements in early independent Latin America. The federalist viewpoint held significant sympathy in New Granada and Quito as well, with Vice President (and acting President during Bolívar's absence from Colombia) Francisco de Paula Santander among its chief advocates. However, it was strongest in Venezuela, where José Antonio Páez, the Military Governor of Caracas, had led the La Cosiata rebellion [5] in 1826 against the central government (…) Páez was unwilling to recognize Santander's rule over Venezuela, but when Bolívar himself returned to power, Páez agreed to end the revolt in exchange for retaining his position as governor…

…Having re-established his authority in Bogotá, Bolívar decided that since the existing state of affairs was clearly untenable, a second constitutional convention should be held to amend the Cúcuta constitution and provide a new settlement that would make Colombia governable. The convention was called to Ocaña, assembling in April of 1828, and conflict immediately broke out between federalists and centralists. Bolívar wanted to use the convention to push for his ideal form of government, as expressed in the Bolivian constitution of 1826 [6], believing that this would bring stability to the country's government and allow him to take control over the separatist regions [7]. However, this sentiment was opposed by the majority of the delegates, notably Vice President Santander as well as nearly every single provincial leader, who argued that the size of the country and the poor state of communications would make the country ungovernable from a central location. Bolívar's determination and stubbornness was the main thing preventing the federalists from imposing their will on the convention, and with the president of the nation shoring up the minority side with all the ferocity that had driven the Spanish out of most of a continent, the convention remained deadlocked for weeks.

Then, on May 15th, something unexpected happened. During a negotiation session, Bolívar suddenly slumped down in his seat, his head banging against the table, and remained still for several minutes as the room went into a blind panic. The nearest physician was sent for, and took the Liberator into a separate room where a bed was set up. A quick examination appeared to confirm that Bolívar had suffered a severe heart attack, and that with the relatively spartan medical resources in the provincial town, it appeared likely that this would be his deathbed…

…In the end, as feared, the physicians of Ocaña proved unable to save the Liberator. He spent the following day on his deathbed going in and out of consciousness, during which time he saw Santander and several other leading figures of the convention. He did not, of course, have any close relatives who could be summoned, but his mistress Manuela Sáenz was by his side throughout. His final words were spoken to her, minutes before slipping back into unconsciousness, and have been lost to history; we do, however, know what the last thing he told Santander was, because the latter used the words in his address to the convention on the 17th – “Keep the nation together, keep the revolution alive” – although we obviously have no way of knowing whether this was actually true or if Santander fabricated the statement for dramatic effect… [8]

…The convention assembled hastily on the following day, and with little debate, agreed to proclaim Santander as the new President of Colombia for two years, with regular elections to be held in July of 1830. The federalists now decisively held the upper hand, and the convention could soon agree on a new constitution, which was in effect mainly an amendment of the Cúcuta constitution. The main change was that the departments would be significantly more autonomous, with the intendants abolished in favor of governors elected by the assemblies of their department [9]. Otherwise most of the provisions remained in place, and the twelve existing departments [10] would remain in place for the foreseeable future…

***

From “Colombia: The Early Years”

(c) 1988 by Garrison Fernandez

Philadelphia: United Press

…By the time Santander replaced the departed Bolívar as chief executive, the situation, although less troublesome than previously, remained precarious. The regional revolts had simmered down for the time being, but as long as the war against Spain continued to rage, the economic situation would mean continued unrest. Fortunately for Santander and for Colombia, the situation in Spain would soon change. The overthrow of Charles X of France in July of 1830 meant that Ferdinand VII had lost his most important foreign ally, thus weakening his position considerably. Implored by his advisors not to overextend his empire, King Ferdinand decided to shift focus to consolidating the remainder of it. To this end, a ceasefire – not a formal peace, nor formal Spanish recognition of independence – was offered to Colombia, and President Santander accepted it wholeheartedly. The nation was at peace, and the crisis appeared over. Colombia appeared to be on the path to stability…

***

[1] A large number of Irish Catholics took up service under the Spanish crown; O'Donojú's ancestor was one of them, but he himself was a Spaniard by birth.

[2] I've skipped over a significant part of Iturbide's rule, including when the gradually worsening economic situation got to the point where he was unable to pay his men.

[3] Not making this up, early Mexican politics were quite literally run by warring groups of Freemasons. The more I read into this the more I'm convinced that the Anti-Masonic Party was on to something.

[4] IOTL, the army did launch a rebellion in support of Guerrero's candidacy, and eventually got Gómez Pedraza to concede the election, starting a long tradition of military interference in presidential politics which would result in no president between Victoria and José Joaquín de Herrera (1848-51) completing a full term in office. ITTL, with the peaceful transfer of power between Victoria and Gómez Pedraza, this is somewhat nipped in the bud, although I wouldn't be able to change the nature of Mexican politics enough to stop the army being a factor altogether without a much earlier PoD.

[5] Cosiata is a local Spanish colloquialism meaning something like “thingamajig” (or so I'm told).

[6] This was a rather weird form of quasi-republican parliamentary government, inspired by what Bolívar saw as the most stable democracies thus far created, namely ancient Rome and Great Britain. The system would've had a President appointed for life and able to choose his successor, with very limited powers except over national defense and overseeing the other executive officials. Power would instead be vested in a tricameral parliament, consisting of an elected Chamber of Tribunes who would hold power over matters of fiscal policy and have the sole right to declare war, a hereditary Senate appointed by the President who would oversee the judiciary and appoint regional officials, and a body of Censors who would act as a check on the other two houses' power in the name of the people – Bolívar was unclear on how these would be selected, but their neutrality would've been essential to the operation of government. Naturally, the book covers this system during its chapter on the Bolivian constitutional convention, which is why I need to explain it in a footnote here.

[7] Bolívar was, to say the least, a bit of a control freak.

[8] IOTL, Bolívar's health was in decline at this point, but he survived until the end of the convention, which would've produced a federalist constitution had he not ordered his supporters to withdraw from it, leading to its disbandment. He subsequently tried to push his centralist agenda through regardless, but was frustrated at every turn, and resigned in April of 1830, intending to go into self-imposed exile in Europe. However, he died in Cartagena before he could set sail.

[9] The Cúcuta constitution (which predates the PoD) provided for most federal offices to be elected indirectly by an assembly of electors in each province, who were elected by voters in each canton (a level between the province and parish). The departments, which consisted of several provinces each, were to be governed by intendants appointed by the President; here that provision is replaced.

[10] One department (Istmo) corresponding to OTL Panama, three (Ecuador, Guayaquil and Azuay) corresponding to OTL Ecuador, and four each corresponding to OTL Colombia (Boyacá, Cauca, Cundinamarca and Magdalena) and Venezuela (Maturín, Orinoco, Venezuela and Zulia).

Last edited:

To be honest Ares, most of the left in Catholic countries in the 19th century was made up of basically Freemasons. In fact, membership (and rank) in the sects tended to go side by side with rising political influence on the left.

And most of the right was associated with the church, I assume?

And most of the right was associated with the church, I assume?

Essentially. The clerical vs. anti-clerical divide was very deep for this reason. That and anti-clericalism was rather popular amongst the masses (ideal for revolts) and when socialism appeared, they had to become more anti-clerical than the anti-clerical liberals in order to then be able to spread socialist ideas, given anticlericalism's popularity, in the cities anyway.

By the way, although I don't know enough about South American politics to comment, it does seem that both Mexico and Gran Colombia are headed so far for a better period than OTL. But I guess that's not saying much.

Share: