Chapter Thirty-Seven

Grant & the Two Porters

-v-

the Gardner of Port Hudson

-v-

the Gardner of Port Hudson

From “The Fighters – Grant v Bragg on the banks of the Mississippi” by Nelson Cole

LSU 1991

LSU 1991

“The Siege of Port Hudson occurred from May 4 to June 2, 1863, when Union Army troops assaulted and then surrounded the Mississippi River town of Port Hudson, Louisiana. In cooperation with Major General Fitz-John Porter's advance from Baton Rouge, Major General Ulysses Grant’s army moved against the Confederate stronghold at Port Hudson...

According to historian Morgan Withers, "Port Hudson, unlike Baton Rouge, was one of the strongest points on the river, and batteries placed upon the bluffs could command the entire river front."

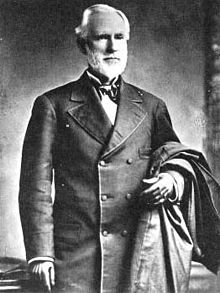

In May 1863, Union land and naval forces began a campaign they hoped would give them control of the full length of the Mississippi River. One army under Grant commenced operations against the Confederacy's fortified position at Vicksburg at the northern end of the stretch of the river still in Southern hands. At about the same time, another army under Fitz-John Porter moved against Port Hudson, which stood at the southern end…

The renewed support for the war brought about by the death of General Hunter galvanized the Lincoln administration into action. Major General Fitz-John Porter was diverted from a possible expedition to Mobile and given orders to take Port Hudson. The Union commander of all armies, Henry Wager Halleck stated to Porter that President Lincoln “regards the opening of the Mississippi River as the first and most important of all our military and naval operations, and it is hoped that you will not lose a moment in accomplishing it”…”

From “The Bloody Crucible – The Siege of Port Hudson” by Morgan Withers

LSU 1983

LSU 1983

“Port Hudson began as a village sited on an 80 foot bluff on the east bank above a hairpin turn in the Mississippi river 25 miles upriver from Baton Rouge. The hills and ridges in the area of the town represented extremely rough terrain, a maze of deep, thickly forested ravines, swamps, and cane brakes giving the effect of a natural fortress. The town had appeared and grown as a point for shipping cotton and sugar downriver from the surrounding area. Despite the growing shipping business the town itself remained small, consisting of a few buildings and 200 people by the start of the war…

General Bragg had by this time realized that linking the Port Hudson and Clinton railway to Jackson, Mississippi would be invaluable in allowing reserves to be switched between Vicksburg and Port Hudson, depending upon which was most threatened. A desperate shortage of iron and transport within the Confederacy made this move impossible…

Poor supply lines, starvation, and disease were to remain the constant problems of the Port Hudson position, and overwhelm efforts to improve conditions for the soldiers of the garrison. Louisiana Private Robert D. Patrick wrote: “never since I have been in the army have I fared so badly and in truth I have been almost starved.” At the same time commercial activity between Port Hudson and areas west of the Mississippi increased, because Port Hudson and Vicksburg were the last remaining links with the Trans-Mississippi. This tended to tie up even more of Port Hudson’s limited transport facilities…

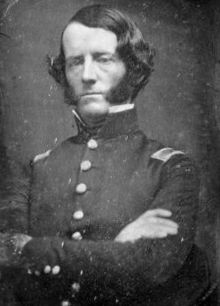

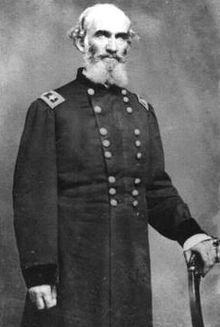

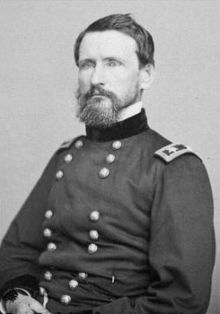

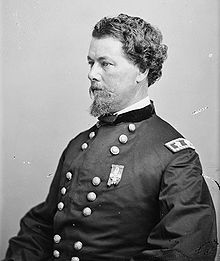

The arrival of Lincoln’s new commander of the Gulf, Fitz-John Porter, appeared to herald renewed action for the approximately 31,000 Union troops in New Orleans and the southern Louisiana area. The Confederate command reacted to this increased Union commitment by sending a new major general to take command of Port Hudson. Major General Franklin Gardner arrived at his post on the 27th of December 1862. Gardner was a career army officer who graduated from West Point 17th in his class in 1843. The native New Yorker commanded a cavalry brigade at Shiloh and was 39 years old at the time of his arrival. Upon taking command he reorganized the defenses at Port Hudson, concentrating the fields of fire of the heavy guns and setting up more earthworks using packed earth and sod rather than the traditional gabions or sandbags…

Fitz-John Porter busied himself in anticipation of the attack on Port Hudson with his usual slow but thorough preparations. What finally brought him to move on Port Hudson was the prospect of uniting with Grant’s army, currently maneuvering against Vicksburg, and word that a significant part of the Port Hudson garrison had been sent to Bragg in Vicksburg. When Grant’s attempts to force a lodgment south of Vicksburg stalled at Port Gibson, he sent word to Porter to meant him at Port Hudson…

Leading the advance was the cavalry brigade of Colonel Benjamin Henry Grierson, which had just joined Porter’s forces on April thirtieth after its raid through the Rebel lines. The entire advance involved a pincher movement with three army divisions advancing from the northwest from Bayou Sara meeting two divisions advancing from the south from Baton Rouge. The meeting of the two groups would surround Port Hudson pending the arrival of Grant’s force…

Leading the advance was the cavalry brigade of Colonel Benjamin Henry Grierson, which had just joined Porter’s forces on April thirtieth after its raid through the Rebel lines. The entire advance involved a pincher movement with three army divisions advancing from the northwest from Bayou Sara meeting two divisions advancing from the south from Baton Rouge. The meeting of the two groups would surround Port Hudson pending the arrival of Grant’s force…

Once Porter had completed the investment of the Port Hudson defenses he anticipated a formal siege. The arrival of Grant with the corps of McClernand and Sherman changed that. Grant hoped to overrun the entrenchments quickly, then take his army northward to attack Vicksburg…

General Gardner chose to reinforce the picket lines shielding the Confederate grain mill and support shops of the areas near Little Sandy Creek because he did not consider a siege probable, and had not fortified that perimeter. Other Confederate troops remained outside the fortifications, consisting of 1200 troops under the command of Colonel John L. Logan. These represented all of Gardner’s cavalry, the 9th Louisiana Battalion, Partisan Rangers, and two artillery pieces of Robert’s battery. These troops slowed the encirclement of Porter’s troops, and prevented them from discovering the weaknesses in the defenses. With Grant’s arrival the infantry assault was scheduled for the 8th of May. The short delay between the encirclement by Porter and the arrival of Grant had allowed Gardner to complete the ring of defenses around Port Hudson. He also had sufficient time to move some artillery from the river side of the fort to the east side fronting the Federal forces…

Grant had set up his headquarters at Riley’s plantation and planned the attacks with his staff and corps commanders. Porter was opposed to the idea of trying to overwhelm the fort with a simple assault, but Grant wanted to end the siege as quickly as possible in order to move on Vicksburg before the rebels could react in force, and felt that the 50,000 troops available to him would easily force the surrender of the 7,500 troops under Gardner, a seven to one advantage. Despite his reluctance, General Porter was given the task of organizing the assault. Four different assault groups were organized, under the commands of generals Godfrey Weitzel, Cuvier Grover, James B. Ricketts, and Thomas W. Sherman. Porter indicated dawn for his intended simultaneous attack…

Generals Weitzel and Sherman attacked on the north and northeast sides of the fort at dawn. However Ricketts was slow to get into action and Grover held off pending confirmation that Ricketts was ready. This meant that the attack on the east and southeast sides commenced at 10.30am. The naval bombardment began the night before the attack, firing most of the evening, and the upper and lower fleets beginning firing for an hour after 7am. The army land batteries also fired an hour bombardment after 5am. Weitzel’s and Sherman’s two divisions began the attack at 6am on the north, advancing through the densely forested ravines bordering the valley of Little Sandy Creek. This valley led the assault into a salient formed by a fortified ridge known as the “Bull Pen” where the defenders slaughtered cattle, and a lunette on a ridge nicknamed “Fort Desperate” which had been hastily improvised to protect the fort's grain mill.

At the end of this ravine between the two was a hill described as “Commissary Hill” with an artillery battery mounted on it. The Union troops were caught in a crossfire from these three positions, and held in place by dense vegetation and obstacles placed by Rebel troops that halted their advance. The combination of rugged terrain, a crossfire from three sides, and rebel sharpshooters inflicted many casualties. The Union troops advancing west of the Bull Pen were caught between the Bull Pen, which had been reinforced with three Arkansas regiments from the east side of Port Hudson, and a more western fortified ridge manned by Lieutenant Colonel M. B. Locke’s Alabama troops. Once again the combination of steep sided ravines, dense vegetation, and a rebel crossfire from ridge top trenches halted the Union advance. Premature shell bursts from the supporting artillery of the 1st Maine Battery also caused Union casualties…

Seeing that his advance had been stopped, Brigadier General William Dwight ordered the Louisiana Native Guards forward into the attack. These troops were not intended to take part in the attack due to the general prejudice against negro troops on the part of General Porter. Dwight was determined to break though the Confederate fortifications however, and committed them to the attack at 10 am. Since they had been deployed as pioneers (for which they had initially been raised), working on the pontoon bridge over Big Sandy Creek near its junction with the Mississippi, these troops were in the worst possible position for an attack than all the units in Weitzel’s northern assault group.

The Guard first had to advance over the pontoon bridge, along Telegraph Road with a fortified ridge to their left manned by Mississippi troops supported by a light artillery battery, the Confederate heavy artillery batteries to their front, and the Mississippi river to their immediate left. Despite the heavy crossfire from rifles, field artillery, and heavy coast guns, the Louisiana Native Guards advanced with determination and courage, led by Captain Andre Cailloux, a free black citizen of New Orleans. Giving orders in English and French, Cailloux led the Guard regiments forward until injured by artillery fire. Taking heavy losses, the attackers were forced to retreat to avoid annihilation. This fearless advance did much to dissipate any remaining doubts in the Western armies that negro troops were unreliable under fire…

The attack of the Louisiana Native Guards

While the infantry attacks raged against the northern section of the fortress, General Porter had sought to line up 38 cannon opposite the eastern side of the fortress and conducted a steady bombardment of the rebel works and battery positions, supported by sharpshooters aiming for Confederate artillery crews. This effort had some success, but General Grant, upon hearing no massed rifle fire from the Union center, visited Grover’s headquarters and threatened to relieve him of command unless he advanced his troops. Grover then began the attack on the eastern edge of the Port Hudson works at about 10.30am.

These attacks included some of the troops of Ricketts as well as his own, and had less in the way of natural terrain obstacles to contend with, but in this area the Confederates had more time to construct fortifications, and had put more effort and firepower into them. One feature of the earthworks in this region was a dry moat and more abatis in front of the parapet. The Union negro pioneer companies, mostly former Louisiana slaves, carried axes, poles, planks, cotton bags and fascines to fill in the ditch and effectively led the attack...

When the Union infantry closed within 150 yards they were met by a hail of rifle and canister fire, and few made it within 50 yards of the Confederate lines. Grover was wounded in these attacks, and Lieutenant Colonel James O'Brien, commanding the pioneer companies, was killed. At 3pm Union troops raised a white flag to signal a truce to remove the wounded and dead from the field. This ended the fighting for the day. None of the Union attacks had even made it to the Confederate parapets…

The successful defense of their lines brought a renewed confidence to Gardner and his garrison. They felt that through a combination of well planned defensive earthworks and the skillful and deliberate reinforcement of threatened areas, the superior numbers of attackers had been repulsed. Learning from his experience, Gardner organized a more methodical system of defense. This involved dividing the fortifications into a network of defense zones, with an engineering officer in charge of strengthening the defense in each area. For the most part this involved once again charting the best cross fire for artillery positions, improving firepower concentrations, and digging protective pits to house artillery when not in use, to protect them from enemy bombardment…

Spent bullets and scrap metal were sewed into shirtsleeves to make up canister casings for the artillery, and the heavy coast guns facing the river that had center pivot mounts were cleared for firing on Union positions on the eastern side of the fortress. Three of these guns were equipped for this, and one 10-inch Columbiad in Battery Four was so effective in this that Union troops referred to it as the “Demoralizer." Its fearful reputation spawned the myth that it was mounted on a railroad car, and could fire from any position in the fortifications. Rifles captured from the enemy or taken from hospitalized soldiers were stacked for use by troops in the trench lines.

Positions in front of the lines were land mined with unexploded 13-inch mortar shells, known as “torpedoes” at the time. Sniper positions were also prepared at high points in the trench works for sharpshooters. These methods improved the defense, but could not make up for the fact that the garrison was short of everything except gunpowder. The food shortage was a drag on morale, and resulted in a significant level of desertion to the enemy. This drain on manpower was recorded by Colonel Steedman who wrote, “Our most serious and annoying difficulty is the unreliable character of a portion of our Louisiana troops. Many have deserted to the enemy, giving him information of our real condition; yet in the same regiments we have some of our ablest officers and men”…

On the Union side, astonishment and chagrin were near universal in reaction to the decisive defeat of the infantry assaults. Grant was furious at the setback. Porter too was unimpressed with the performance of several of his commanders notwithstanding his previous opposition to any attack. Ricketts was promptly relieved of his command for his delay. He would not be re-employed…

The resources of the entire command were now called into play, and men and material poured into the Union encirclement. General Porter took command of all the artillery at hand and began a relentless bombardment of the Rebel works…

Union batteries during the Siege of Port Hudson

The second assault began with a redoubled shelling of the Confederate works beginning at 11:15am on June 1 and lasting an hour. Grant then sent a message to Gardner demanding the surrender of his position. Gardner’s reply was, “My honor and my duty require me to defend this position, and therefore I decline to surrender”. Porter continued the bombardment during the night, and Grant gave the order for what was to be a simultaneous three prong infantry attack at 1am on June 2. The attack began at 1:30am. McClernand’s corps led the assault from the north.

McClernand was keen to swipe anyway any stain on his reputation from Port Gibson. It was the most difficult sector to assault but as William T. Sherman observed “McClernand was aggressive. Regardless of the position or odds. Perhaps the most aggressive general in Grant’s army. He was the only person who wanted to fight even when Grant did not”. His column struck the Confederate line at “Fort Desperate” before the other columns reached the Rebel lines, and the same formidable terrain combined with the enhanced Confederate defense almost stopped the attack outside the rebel works. William T. Sherman's attack in the center, spearheaded by Steele’s Division, and the attack on the southern end of the line by Fitz-John Porter’s troops, arrived in time to prevent any attempts by Gardner to reallocate his troops within the works – he was attacked all along the line.

Porter’s troops redeemed themselves by being the first to break through the defenses, closely followed by McClernand’s troops under Eugene Carr. Rebel troops quickly began to stream from the outer defenses into the small town and inner defenses…

As dawn broke General Grant demanded the surrender of General Gardner. Gardner prevaricated for a almost a day before surrendering on June 2. General Porter assembled some of his “eastern” troops at the corps headquarters and thanked them for their brave efforts and sacrifices. In response General McClernand gave a speech of praise to his “westerners”. In historian John Murdoch’s opinion “a war of words now erupted between the easterners and westerners in Grant’s army that was to poison some relationships, while prompting a competition that would spur both factions to greater deeds”…”

From “Vicksburg or Bust” by John W. Scharf

Empire 1984

Empire 1984

“The surrender gave the Union almost complete control of the Mississippi River and its major tributaries, save for Vicksburg. Both sides suffered heavy casualties: between 5,000 to 5,750 Union men were casualties, and an additional 7,000 fell prey to disease or sunstroke; Gardner's forces suffered around 1,300 casualties, from battle losses and disease...

In the west the reputation of black soldiers in Union service was enhanced by the siege. The advance of the Louisiana Guard had gained much coverage in northern newspapers. The attack was repulsed, due to its hasty implementation, but was bravely carried out in spite of the hopeless magnitude of opposing conditions. This performance was noted by the army leadership: “One thing I am glad to say, that is that the black troops at P. Hudson fought & acted superbly. The theory of negro inefficiency here is, I am very thankful at last thoroughly exploded by facts. We shall shortly have a splendid army of thousands of them.” General Porter, under who command the bulk of negros served, also noted their performance in his official report, stating, “The severe test to which they were subjected, and the determined manner in which they encountered the enemy, leaves upon my mind no doubt of their utility as disciplined troops.” These observations did much to support the substantial efforts already underway to recruit free blacks for the Union armed services following the death of General Hunter…

In the west the reputation of black soldiers in Union service was enhanced by the siege. The advance of the Louisiana Guard had gained much coverage in northern newspapers. The attack was repulsed, due to its hasty implementation, but was bravely carried out in spite of the hopeless magnitude of opposing conditions. This performance was noted by the army leadership: “One thing I am glad to say, that is that the black troops at P. Hudson fought & acted superbly. The theory of negro inefficiency here is, I am very thankful at last thoroughly exploded by facts. We shall shortly have a splendid army of thousands of them.” General Porter, under who command the bulk of negros served, also noted their performance in his official report, stating, “The severe test to which they were subjected, and the determined manner in which they encountered the enemy, leaves upon my mind no doubt of their utility as disciplined troops.” These observations did much to support the substantial efforts already underway to recruit free blacks for the Union armed services following the death of General Hunter…

Grant’s mind now turned to Vicksburg with Fitz-John Porter’s XIX Corps as a sorely needed reinforcement…”

Last edited: