I stand correctedChapter 1 already states that one hundred thousand soldiers were left for peacekeeping, which largely lines up with OTL. IOTL, more than 800,000 men had been discharged and another 190,000 by spring 1866. Demobilization was popular and in line with the anti-military disposition . That said, the demobilization of USCT could definitely be avoided, which was justified as a measure to placate Southerners. Retaining the cavalry volunteers or converting some USCT regiments to cavalry units would also be good for counter-insurgency.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Reconstruction: The Second American Revolution - The Sequel to Until Every Drop of Blood Is Paid

- Thread starter Red_Galiray

- Start date

Thank you for your kind words! I'm really glad you liked the first TL, I hope you will like this one too.Saw this, checked it out and discovered it was a sequel to another TL so I went and binged that before coming back. I gotta say, that was an amazing TL and I cannot wait to see how this one will turn out. Eagerly waiting for additional updates.

Given the circumstances of his birth, he very well could have died in the famine. But, assuming he lives, since many of his relatives were actual Klansmen, he very well could see the Klan put down by Federal force, maybe even see his uncle, a local leader of the Klan, executed or imprisoned. He's likely then to just be more racist and embittered against Reconstruction, but his novels would probably see much less success.In accordance with me asking about D. W Griffith in the original thread, may I ask what happened to Thomas Dixon Jr. ITTL? Assuming he was still born in North Carolina in 1864. IOTL he was an author who wrote racist novels that supported white supremacy and opposed racial equality for blacks, most notably his novel The Clansman (1905) was later adapted into a popular play and then the infamous blockbuster movie Birth of a Nation (1915) directed by the aforementioned D. W. Griffith, which has gone on to be called the most racist film in Hollywood history.

Probably, yeah. He's the one who could claim to the Junta's main opposition, and given that Lee died he could appropriate his legacy, saying he was Lee's true successor, with Jackson being little more than an usurper.I wonder if James Longstreet ends up in a far better position than he was OTL, given he's the "living martyr" of the Junta plus earning the respect of the Union for surrendering at the time he did.

Something like that, yes.Oh I expect the Union to parade Longstreet out and, once he's proven his loyalty, actually give him a position of influence. He could potentially end up as a Reconstruction Governor if he proves his worth - he's be able to speak to disenfranchised Southrons, explain how he had believed in the Cause, but came to see it for how wrong it was and ha to stand up to the Junta in order to protect the soldiers he cared about. If he shows a willingness to work with Freedmen, he could basically become the prototype of the "Good Confederate" - and it would make sense for the Union to push him when and where they can

Yeah, if we show Southerners that supporting Reconstruction can pay dividends, the whole process would be strengthened, and much less likely to be seen as a foreign imposition. In other words, we need more Scalawags, less Carpetbaggers.And promoting people like Longstreet and co would help ensure that the Union does not have its own equivalent to Britain's "Irish Problem" except the size of a continent by making it clear to White Southerners that Reconstruction, if they play ball and keep their head down, was not the end of the world.

I could see him command National Guard units to fight against terrorism, basically a more successful version of his efforts commanding the Metropolitan Police in New Orleans.Hello,

Longstreet may be placed in a way that lets him continue to serve the US and putting him out of the way until he fades into obscurity. I think he wishes not to draw more attention to himself after his defection helped by Grant. So, this may happen like in OTL ...

Never heard of them, I'm afraid, but given that they seemed involved with Democratic politics, a lot of their life would depend on what cart they hitch themselves to. Ohio probably sees the main opposition being Pendleton-style advocates of inflation.I wonder how the Fighting McCooks fared in this timeline.

In OTL they were two brothers from Ohio: Daniel McCook and John James McCook, along with the 13 sons of both, who all served in the Union military. Daniel died during the war, becoming a war hero, while many of the second generation went on to have political ambitions. George Wyth McCook would serve as the AG of Ohio and was a losing Democratic candidate for governor. Edwin Stanton McCook would be named the Secretary of the Territory of Dakota before being assassinated in 1873 due to a personal dispute with another leading figure in the territory. Edward Moody McCook would be named the territorial governor of Colorado, and John James McCook Jr was a prominent NY lawyer and railroad executive. A number of other passed away during the war in various battles.

Rather fascinating group - most known for their temper and gungho attitude.

Would be some interesting stories you could spin off of these guys. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fighting_McCooks

Yeah, that was my own impression as well. Longstreet would be THE Good Confederate ITTL.I could see Longstreet acquiring a public reputation that's a sort of mix between popular perceptions of Rommel and von Stauffenberg.

Emphasis on the "popular perceptions" part mind.

This was something that we discussed very often in the old thread. The consensus is that eventually we will see labor struggles, and that that's probably going to be the breaking point for the Republican Party, which will divide into Liberal and Labor wings. Likewise, a successful Reconstruction opens all sorts of possibilities for biracial populist movements.How about labor struggles? Given that a radical labor tradition gained steam from 1865 onwards in America, in OTL, with a more radical Reconstruction I can easily see a more popular socialist or labor party gain influence. In particular, the great strike of 1877 could be interesting.

We'll get into that later, but he, along with men like Delany, will play an important part in the initial military occupation and Reconstruction.Reading back I wonder what role will Robert Smalls play in reconstruction considering he has been portrayed as the model African-American solider and otl served as a Representative from South Carolina during Reconstruction

Oh, the greatest challenge I'll have writing this thing is that there so, so much ground to cover. There's a reason why the first comprehensive work on Reconstruction was Foner's book, with him noting in the prologue that several historians had given up before him. I've almost finished the next update, I think I could actually post it today after I finish editing it, but I will need to compartmentalize and analyze one topic at a time. I simply cannot analyze every factor at once, even though they take place simultaneously. We will first focus on social and economic issues, continuing to set the stage, before moving to Federal policies and then the organization of the States and then National politics. Next update will, for example, talk of the Black experience during the Jacquerie, famine, and the initial occupation, which is affected by demobilization, but I can't get into the details for now. We will analyze how demobilization occurs and how it affects Reconstruction a little later.Speaking of which, how much would this TL’s first chapters discuss demobilization of the wartime Army and how it affects Reconstruction?

It's inevitable. The US had little desire to keep a million men down South, for such a large standing army was enormously expensive, the public wanted the boys back home, and most politicians seemed unable to appreciate just how demanding the enforcement of their laws would be. Even Radicals like Sumner or Butler consistently voted to downsize the Army. Instead I want to organize cheaper, better motivated, and more permanent Constabulary and National Guard units, and increase the quality of the regiments that are down South.There may not be much demobilization they need the army to help keep peace in the south.

Yes, at the very least we'll see more USCT regiments and more cavalry units, at least during the pivotal first year of occupation.Chapter 1 already states that one hundred thousand soldiers were left for peacekeeping, which largely lines up with OTL. IOTL, more than 800,000 men had been discharged and another 190,000 by spring 1866. Demobilization was popular and in line with the anti-military disposition . That said, the demobilization of USCT could definitely be avoided, which was justified as a measure to placate Southerners. Retaining the cavalry volunteers or converting some USCT regiments to cavalry units would also be good for counter-insurgency.

Last edited:

Moving to something else I've been thinking... could in the next few decades a freedman President be elected out of the grouping of freedman politicians that are undoubtedly going to stick around ITTL where they faded into the background OTL?

Imagining both's OTL positions reversed is just hilarious.Probably, yeah. He's the one who could claim to the Junta's main opposition, and given that Lee died he could appropriate his legacy, saying he was Lee's true successor, with Jackson being little more than an usurper.

that would be insane in a good way.Moving to something else I've been thinking... could in the next few decades a freedman President be elected out of the grouping of freedman politicians that are undoubtedly going to stick around ITTL where they faded into the background OTL?

Imagining both's OTL positions reversed is just hilarious.

but alas unlikely until this generation dies out and there's no hard feelings left

so 1910 maybe

but also the practical reason it'd be hard to choose such a politician due to the lack of information about the freedman poltilcos at ths time.

but actually I think some abiolianist newspapers actually said "it's not over till there's a black president " so maybe

If Reconstruction is a success in the US as @Red_Galiray says, I see the potential for a popularly elected Black President coming in the mid 1930s to early 1940s IMO.that would be insane in a good way.

but alas unlikely until this generation dies out and there's no hard feelings left

so 1910 maybe

but also the practical reason it'd be hard to choose such a politician due to the lack of information about the freedman poltilcos at ths time.

but actually I think some abiolianist newspapers actually said "it's not over till there's a black president " so maybe

Now, I finally join this Timeline, too.

I am excited to see where Reconstruction will lead America. Hopefully, to a better Future than in OTL.

I am excited to see where Reconstruction will lead America. Hopefully, to a better Future than in OTL.

If Reconstruction is a success in the US as @Red_Galiray says, I see the potential for a popularly elected Black President coming in the mid 1930s to early 1940s IMO.

I agree. You could potentially get one sooner by being first nominated as a Vice-President (a nice feel-good measure, to show the rank and file that the party cares for the Freedmen as an interest group) and then the President (in)conveniently shakes off the mortal coil. Though, I suspect that a Freedmen President gaining office in such a way would have a great deal of challanges to his legitimacy and it would be a difficult presidency. If the economy is good, and they really go above and beyond in pushing popular policies and governing effectively, they could find themselves nominated for a term of their own and MAYBE narrowly win.

Its important to remember that this timeline is going to see LESS racism towards Freedmen and their descendents, and the hard racism of Jim Crow , state-mandated segregation laws and the like are not going to exist. But there's still going to be a lot of soft racism and bias in the country that will take a lot longer to go away (or die down to such a level that it can be overcome in the political arena).

Random thought, but Black Americans need their own Henry Clay's, influential politicians that while not gaining the Presidency had a massive impact on future policy throughout the US. Getting decades of black politicians holding their own, and even dominating, in DC will provide great dividends in showing to the American populace their worthiness for accession to the White House.Snip

Last edited:

Yes! I agree so much with this! This is what African-Americans need ITTL to reinforce their worthiness and experience to European Americans, and to show how competent they are to the racists in order to hopefully discredit their theories to the general public, atleast in the sense to show them as civilised people and not savage animals.Random thought, but Black Americans need their own Henry Clay's, influential politicians that while not gaining the Presidency had a massive impact on future policy throughout the US. Getting decades of black politicians holding their own, even dominating, in DC will a great dividends in proving to the American populace their worthiness for accession to the White House.

If one would come out of ITTL civil war, it would probably involve the black version of William McKinley for example (a young soldier)that would be insane in a good way.

but alas unlikely until this generation dies out and there's no hard feelings left

so 1910 maybe

but also the practical reason it'd be hard to choose such a politician due to the lack of information about the freedman poltilcos at ths time.

but actually I think some abiolianist newspapers actually said "it's not over till there's a black president " so maybe

However, I could see reconstruction era black politicians get into high positions like cabinet secretaries or leaders in congress

Chapter 2: We Are Bound for Freedom's Light

Chapter 2: We Are Bound for Freedom's Light

Emancipation and Land Reform in the last months of the war and at the start of the Military Occupation

Emancipation and Land Reform in the last months of the war and at the start of the Military Occupation

Slavery in the United States did not end with the Emancipation Proclamation of July 4, 1862, nor did it end with the final victory over the Confederacy. Instead, and despite the celebrations of Northerners who declared that “slavery and treason are buried in the same grave,” it would take some months more before the 13th amendment was ratified and slavery was ended as a legal institution throughout the nation. But to proclaim the enslaved free did not make them so. Instead, the soldiers of the United States and the enslaved people themselves would have to enforce this freedom, ending slavery as an actual practice and claiming meaningful freedom. The work of emancipation that had started during the war continued through the collapse of the Confederacy, the bloody Jacquerie, and the anarchic situation in the immediate aftermath of the rebel surrenders. And then, after this freedom was secured, new questions regarding its meaning and boundaries had to be confronted. “Verily,” Frederick Douglass declared, “the work does not end with the abolition of slavery, but only begins.”

The continuous war-time erosion of the Confederate State and its power to violently enforce slavery had allowed the enslaved growing opportunities to challenge their masters and claim their freedom. For most of the war, this meant escaping to the Yankee lines. But this could hardly free every slave. Though the Union Armies penetrated deep into Dixie, the path they traced didn’t take them through every plantation in the South. The enslaved found by the advancing Federals would be freed, but most of the time the priority for the armies was to seize strategic cities and infrastructure and keep the enemy in check. Rarely did the Union Armies seek to establish a strong presence in the entire countryside that could free every enslaved person in a given area, for military realities required concentrating against the rebel armies and guarding key points. Consequently, even at the end of the war, a majority of the enslaved had remained in farms and plantations that hadn’t even seen a Yankee soldier during the entire conflict. For all actual purposes, they still hadn’t been freed, notwithstanding all laws and proclamations to the contrary.

While the image of the valiant Black slave defying the planters and escaping to Union lines to fight for the cause of freedom would become ingrained in the consciousness of the Black community and American popular memory, in truth, practical realities kept most Black men from escaping. Of the over 300,000 Black Union soldiers, half came from the Border States and the North, being men who had been free before the war or faced less danger in escaping slavery because they lived in Union-controlled territory. Of the other half, a large percentage were men who had been freed by the arrival of the Federals, rather than by escaping to their lines. Escaping during the war presented great peril, for right until its very collapse the Confederate government kept a strong enough grip over the population it enslaved, being able to capture and severely punish runaways, with whippings, mutilation, or execution. Escape, moreover, would mean leaving relatives and loved ones behind to the tender mercies of the slaveholders, many of whom had openly promised stern punishment to the families of escapees. Taking them along many times wasn’t an option either, for flight exposed them to many dangers such as disease, starvation, exhaustion, or slave patrols, which children or the elderly could very well not survive.

This meant that, even as it steadily and fatally wrecked slavery as an institution, military emancipation by itself failed to completely destroy it. A large number of slaveholders, for example, successfully “refugeed” their human chattel, moving them away from areas threatened by Yankee invasion to the interior or the Trans-Mississippi. Many others, even those near the Federal lines, failed in their efforts to escape, being stopped by Confederate militias. Some never tried, recognizing the dangers they would put themselves and their loves ones in. “Like everybody else, slaves were driven by a complex mixture of incentives and calculations,” writes historian James Oakes. “It cannot have been obvious to all slaves that they should quit their families, neighbors, or homes in exchange for a filthy, overcrowded contraband camp, or the brutal uncertainties of trailing an army on the march.”

It's estimated that, of around four million Black slaves, only one million had been effectively freed by the war's end

Unsympathetic Yankees were quick to assume this reluctance to escape was a sign of loyalty to the masters, or cowardice on the part of the slaves. “Not one nigger in ten wants to run off,” General Sherman complained while stationed in Tennessee. In truth, most probably wanted to flee, but just couldn’t, with a great majority of the enslaved having no option but to stay in their plantations. Even the famously destructive “marches” through Alabama, Georgia, and the Carolinas towards the end of the war were unable to completely free every single slave. “The Yankees swept through plantation districts like a tornado, destroying deserted farms and uprooting slavery along the way,” comments James Oakes. “Like a tornado, though, the severity of the damage ended abruptly at the edge of the storm’s track.” Of some 460,000 enslaved people in Georgia before the war, Sherman’s march only freed around ten thousand; of over 400,000 slaves in South Carolina, only 7,000 were directly liberated during his Carolinas campaign. Oakes concludes: “In the most concerted attack on slavery during the most deliberately destructive campaign of the war, Sherman had dislodged only about 2 percent of the slaves in Georgia and South Carolina.”

Nonetheless, the collapse of Confederate public authority and the retreat of rebel forces from many plantation districts allowed Black people to self-emancipate, seize plantations, and even organize rudimentary governments in the absence of Federal power. Sherman’s and McPherson’s marches through Alabama, as in their future campaigns, freed only a small percentage of the enslaved directly, but because they destroyed the authority of the slaveholders they found themselves unable to enforce slavery anymore. Throughout the State, former slaves declared themselves free, refusing to obey orders anymore, and even seizing lands and property. In one plantation, for example, freedmen told the former owner that “they will git the crop let them work you cant drive them off for this land don’t Bee long to you.” Whenever planters fled or were imprisoned, freedmen were quick to take control. In one plantation they drove away the overseer and declared that “they will not allow any white man to put his foot on it;” in another, the former master fled after he observed the laborers refused to work for him, the only work they completed being the construction of a gallows.

This meant that instead of the formal bureaucratic process Northerners had envisioned, land redistribution on the ground advanced informally and irregularly, with Federals often finding that the freedmen had already seized and divided the lands themselves. “I don’t do any distribution,” a Land Bureau agent wrote. “I only take note of what the negroes did already.” Often, soldiers and agents on the field encouraged defiance and fanned hopes for land redistribution. A group of self-described “loyal planters” thus complained bitterly of “negroes led astray by designing persons” who made them believe that “the plantations and everything on them belonged to them.” One example was the freedman West Turner, who was asked by a Union soldier if he had been whipped by his slaver. He was, Turner answered, at least 39 times. The soldier then advised Turner to take an acre for every stroke, plus one more as a bonus, so Turner “measure off best I could forty acres of dat corn field.” Black soldiers were especially conspicuous in this regard, their mere presence encouraging the dreams of the freedmen. “The Negro Soldiery here,” a Mississippi planter said, “are constantly telling our negroes that for the next year, the Government will give them land, provisions, and Stock and all things necessary to carry on business for themselves.”

Not even declarations of loyalty could stop lands from being forcibly taken. Much to the consternation and horror of many planters, the Land Bureau allowed freedmen to testify as to the loyalty of their former owners in order to determine whether the land should be confiscated. Often, lands were taken before the owner even had an opportunity to take the oath, presenting the Federal agents with a mere fait accompli that would then be ratified after the freedmen declared the owners to have been rebels. One conservative agent at least did question “why we hear the negroes, who have a vested interest in saying their masters were the worst rebels and so to take the land.” But the Federals were reluctant to believe planters that “only remember their love for the government once they see our soldiers at their doorstep,” as a soldier said sardonically. Informed of military orders and Bureau decisions by the grapevine telegraph, freedmen were also quick to appeal to them to justify their actions. The leader of a Home Farm, for example, told the returning planter that “Massa Sherman has said that the land belongs to us the colored people,” and as such the plantation was no longer his property.

Unable to call on rebel soldiers to enforce slavery, and with the Federals proclaiming freedom and often upholding land redistribution, the slaveholders had no other option but to acknowledge the end of slavery. But in areas outside Union control where they could still count on Confederate units or local militias to impose their will, the masters grew more brutal in their methods. Frightened by news of planters who had lost their lands and by exaggerated reports of massacres, the repression faced by the enslaved only increased in the last year of the war and especially after the Coup. Under the auspices of the Southern Junta, more ruthless than Breckinridge had ever been, any sign of defiance or resistance was swiftly crushed, by such methods as publicly hanging corpses or placing the heads of runaways on pikes. Believing that “the roar of a single cannon of the Federals would make them frantic-savage cutthroats and incendiaries,” as James H. Hammond said, the planters just stepped up their campaign of terror.

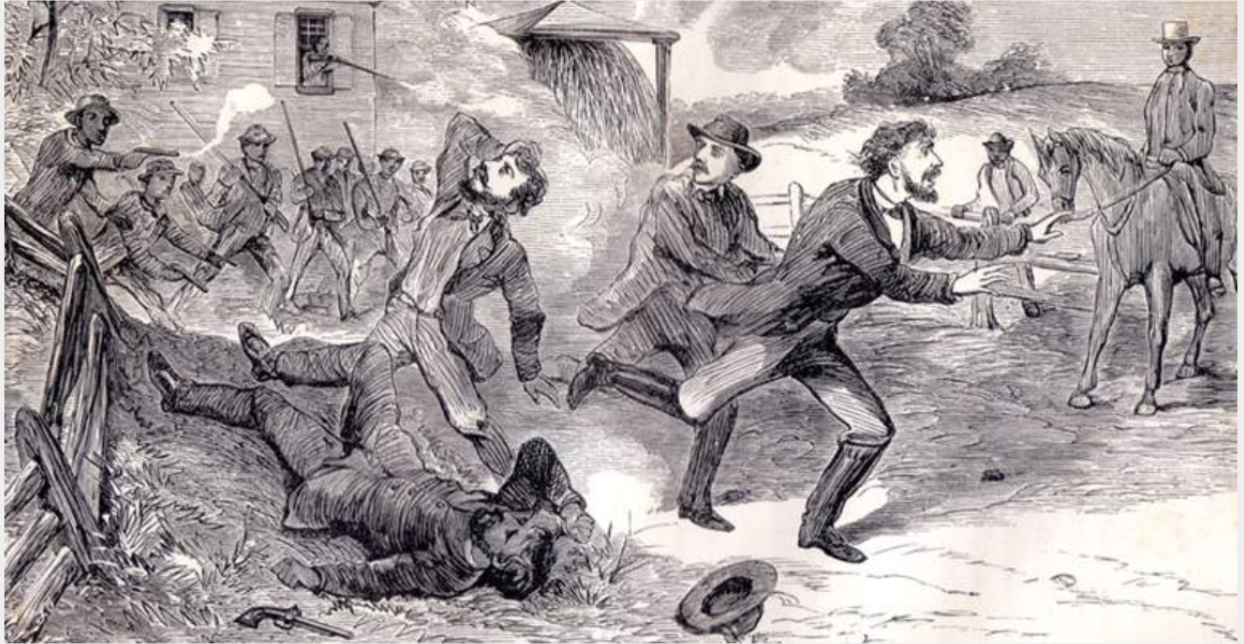

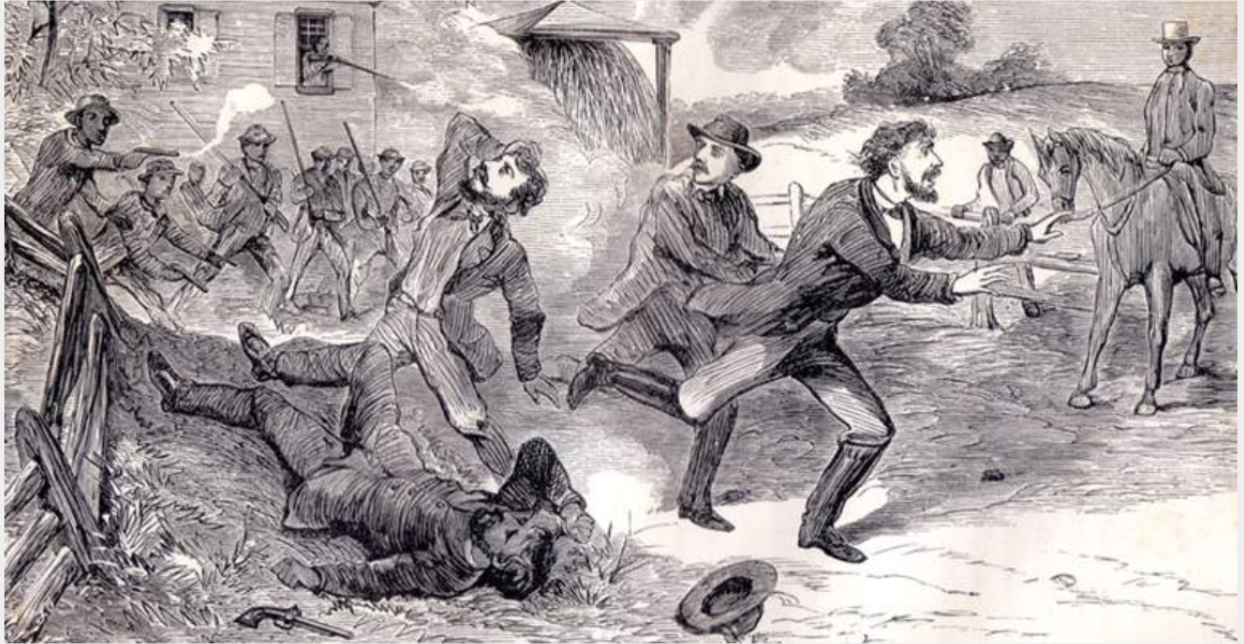

The Jacquerie allowed Black people to claim their freedom and seize plantations

The power of the Confederate State and thus slavery itself started to unravel in the winter when hunger and dissent spread throughout the Southern countryside. In the areas still under Confederate control, the enslaved were usually the first victims of famine, for the enslavers preferred to keep the food for themselves, or even to sell at marked-up prices. The slaves of Charles Manigault’s plantations, for example, had been surviving in meager rice rations, and when the Federals finally freed them close to half had already died by starvation, disease, and malnutrition – which resulted in Manigault being imprisoned, for he still had beef and other supplies he simply had refused to share. Outright violence from the enslaved, heretofore, had been contained by the knowledge that insurrection had bleak odds of success and that bloody punishment would be quick to follow failure, and by hopes that the Federals would soon arrive. But driven by desperate hunger, and with organized Confederate forces dissolving and thus unable to “restore order,” enslaved people in plantation after plantation started to raise up, seizing food stores, driving away owners and overseers, and taking the plantations for themselves.

During the secession crisis, Northerners had repeatedly warned Southerners that “disunion is abolition,” for, as William Seward said, the “ferocious African slave population” could not be expected to “remain stupid and idle spectators” in the middle of a “flagrant civil war,” but would claim their freedom – by violence, if needed. The Springfield Republican likewise apprised Southerners that, once outside the Union, slavery’s “life will be one of constant peril and strife, and, like all great criminals, it will be pretty certain to come to a violent and bloody end.” Such prophecies seemed to finally be fulfilled during the Southern Jacquerie. In the Alabama and Georgia plantation districts, “perfect anarchy and rebellion” reigned, with scores of manorial houses being plundered and torched. At Middleton Place near Charleston, the freedmen even broke into the family graveyard and scattered the bones of previous slavers on the ground. Another South Carolina planter was lynched after he refused to turn the plantation over to his slaves, “his head being split open by blows with a hatchet, and penetrated by shots at his face.” James Hammond’s fears were proven correct when he, too, was murdered by the people he enslaved, who hung up his mangled corpse and danced in circles around it, chanting “I free, I free, I free!”

Hard statistics are hard to come by, muddled as they are by fragmentary reports, wild exaggerations, and untrustworthy rumors, but tens of thousands of slaves freed themselves and seized plantations during the last months of the war and its immediate aftermath. Unlike what some panicking masters declared, however, the Black insurrections did not constitute a “generalized and savage Saint Domingue,” where every White person was murdered. Masters and overseers were usually merely expelled, while there are almost no verified reports of murdered White women or children. The Southern Junta did try to repress the slave insurrections, but as their government crashed down, they simply found themselves unable to do so, especially when poor Whites were also revolting and bread riots engulfed all major cities, including Richmond. The task of restoring order instead fell on the Federals, who could, unfortunately, do little until they were able to establish an actual presence in the areas rocked by the Jacquerie. The most they could do at first was informing freedmen that “any act of violence except for those conducted in strict self-defense,” would be punished, something that may have disincentivized revenge.

Once Yankee boots actually reached the areas in upheaval, they would try to bring in food relief, suppress violence, and settle questions of land and labor. But during the initial chaotic months, decisions could be highly arbitrary, depending more on the personal biases and opinions of the officers on the field than on settled national policy. Some racist officers were prone to believe planters that painted the freedmen as bloodthirsty savages and would thus seek to violently quell insurrection. In North Carolina, one even copied the methods of the Slave Patrols and publicly hung the corpses of three Black men executed for rape and murder. Other officers, however, were more likely to imprison overseers and planters than help them recover their plantations. The paramount concern, however, was allowing for the quick resumption of food cultivation by permitting the freedmen to farm the lands they had seized, all in order to alleviate the famine. “Questions of legality and loyalty,” a Colonel informed a planter who avowed himself loyal, “shall be decided later.”

The Federal actions encouraged the freedmen, who came to believe that the Yankees had already declared the land to be theirs, and thus that when they forcibly took plantations, they were only claiming their own property. When the Federals finally took Richmond, a Black man warned his former owner that “there was to be no more master and mistress now, all was equal . . . all the land belongs to the Yankees now and they gwine divide it out among the coloured people.” A Mississippi slave also testified that “There were a heap of talk about the Yankees a-giving every Nigger forty acres and a mule. I don't know how us come to hear about it. It just kind of got around. I picked out my parcel. All of us did.” Examining the issue, General Rufus Saxton concluded that “Our own acts of Congress and particularly General Sherman’s order, which was extensively circulated among them, further strengthened them in this dearest wish of their heart—that they were to have homesteads.”

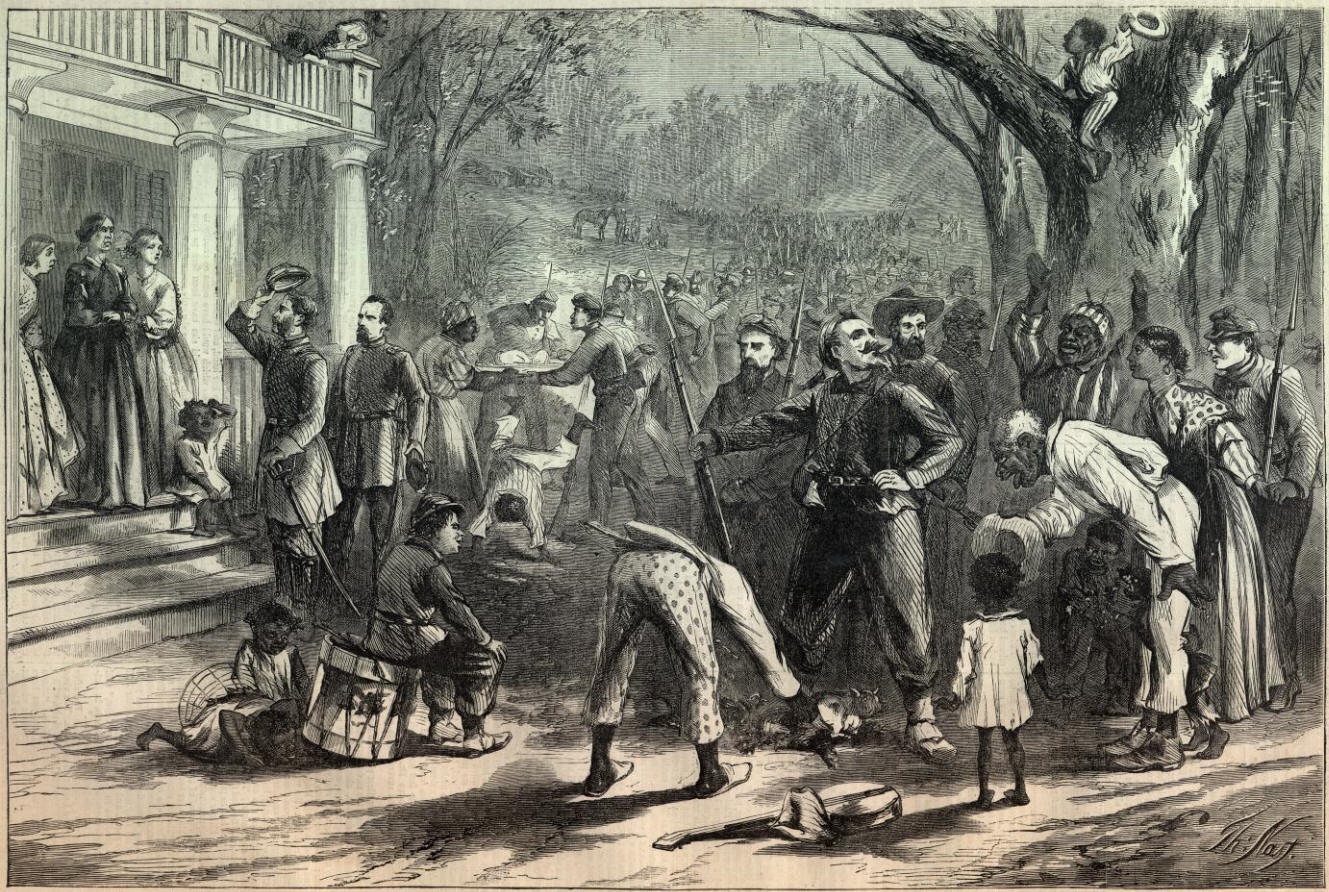

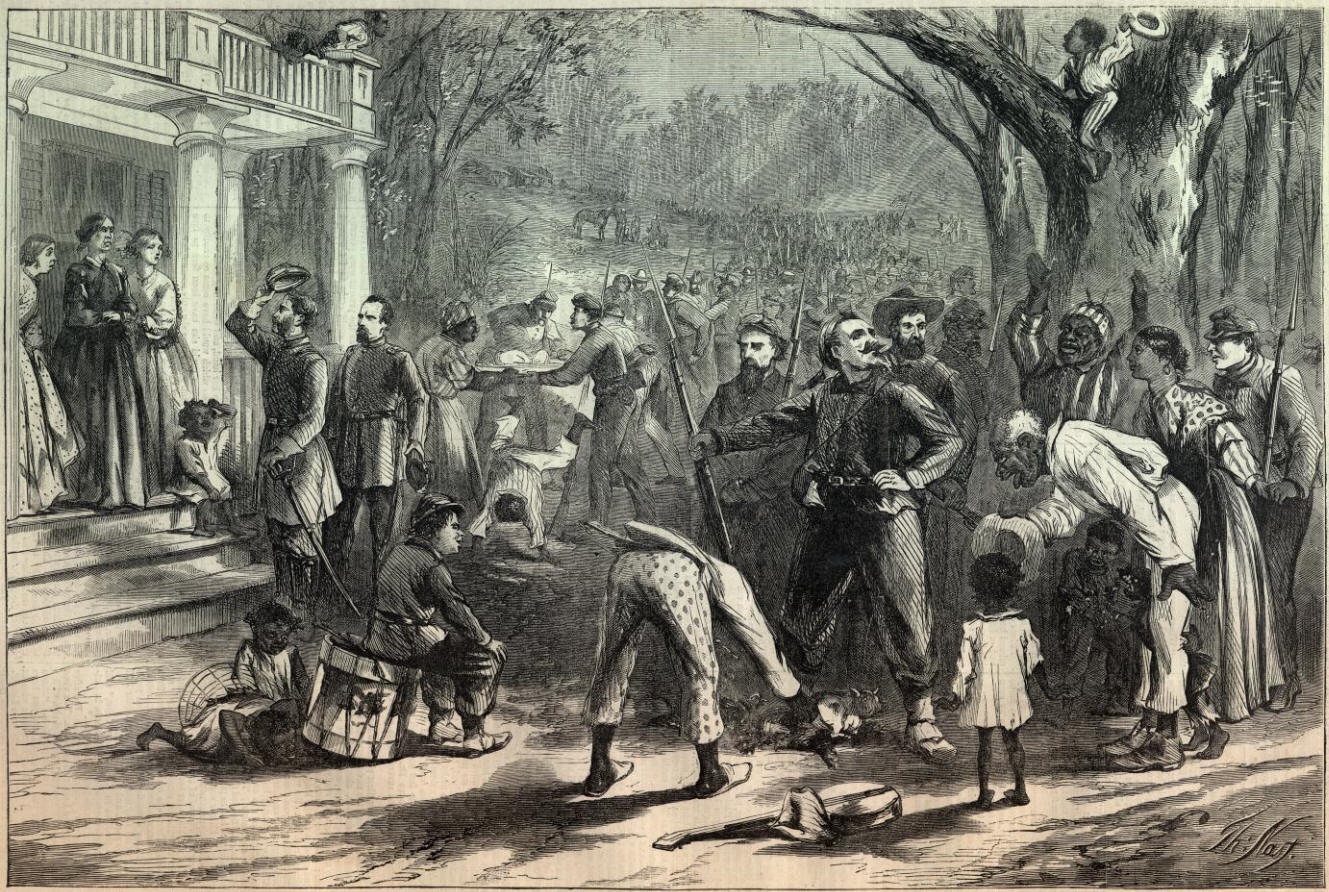

"Emancipation at gunpoint" - to enforce emancipation against rebels who clung to slavery, the US Army had to establish an effective presence in the Southern countryside

However, the freedmen’s possession of the land could prove precarious in the face of continued White resistance and terrorism. For example, after St John’s Berkley Parish in South Carolina was occupied by Black Union troops, the newly freed people took control of several plantations, only to be then attacked by Confederate scouts, who proceeded to hang their leaders and force them to work. Such violence continued well after the organized rebel forces surrendered, with returning Confederate veterans and planters forming militias to try and resist land redistribution and subjugate the freedmen to their will. Describing “rebel savagery,” a Bureau agent said that a group of returning soldiers “took some Freedmen and cut off their ears . . . now and again they ride through the country, using necklaces made with these ears.” Refusing to recognize the end of slavery, much less land redistribution, planters engaged in appalling violence to assert their control. “I saw white men whipping colored men just the same as they did before the war,” claimed the freedman Henry Adams. A guerrilla in Edisto Island, off the South Carolina coast, massacred dozens of slaves after they refused to return the land to the planters.

Such violence was distressingly commonplace in the localities most affected by the Jacquerie and the famine, where a continuous and bloody struggle over food and land continued to rage. But slavery also endured in other areas less affected by the war, where “masters kept some slaves in chains well after the Confederacy’s collapse,” Bruce Levine explains, merely informing “their laborers that nothing had changed.” In Georgia, an African Methodist Episcopal missionary found that as late as August “the people do not know really that they are free, and if they do, their surroundings are such that they would fear to speak of it.” In the same state, a young girl named Charity Austeen remembered how “Boss tole us we were still slaves. We stayed there another year until we finally found out we were free and left.” In Arkansas, the exasperated Colonel Charles Bentzoni found “slavery everywhere;” in Texas, the former masters wanted to ensure that “slavery in some form will continue to exist” by terrorizing their former slaves into obedience, and as late as October there were reports of Black people being “bought and sold as in former years.”

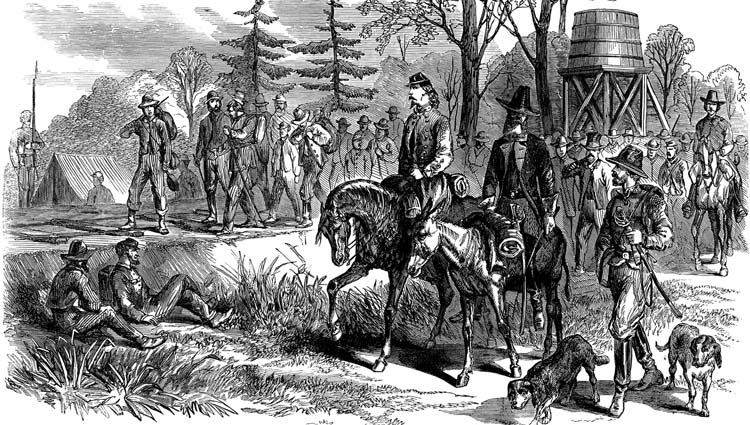

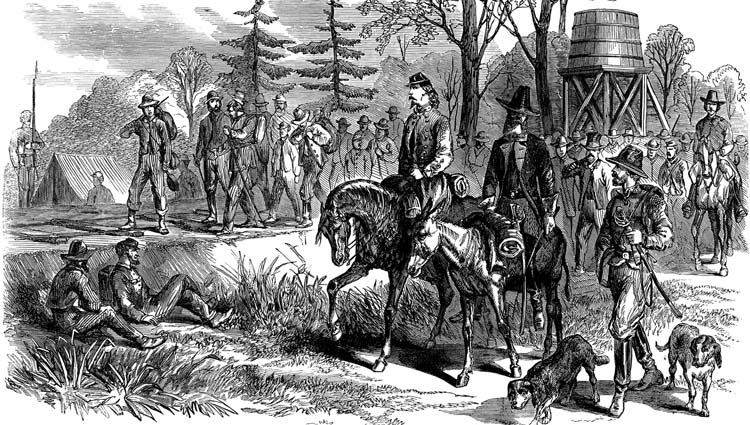

It's no coincidence that most of these reports come from Eastern Arkansas, Texas, and other areas of the Confederate Trans-Mississippi. Separated from the rest of the Confederacy by Grant’s capture of Vicksburg, the Department of the Trans-Mississippi had spent the latter half of the war under the military but also political and economic control of General Kirby Smith. Having refused to recognize the authority of the Southern Junta, Kirby Smith became basically a warlord, controlling his extensive Department and answering to no superior authority. The “Kirby Smith Kingdom,” as it came to be known, remained relatively stable, seeing neither large scale Union invasions, destructive military campaigns, or widespread guerrilla warfare. This is not to say that the Department was in a good condition, for its economic situation was nothing short of calamitous, especially after the Federals closed the illicit trade with Mexico. A Federal officer noted for example that “the people have neither seed, corn, nor bread, or the mills to grind the corn if they had it.” Nor did Smith manage to completely preserve slavery, for it suffered from the same erosion that affected it in the rest of the Confederacy. But compared with the Eastern States that descended into the Jacquerie and famine, the Trans-Mississippi lived relative peace, saw little destruction, and was not affected by hunger or insurrections.

In later years, this would create the impression that Kirby Smith had protected the Trans-Mississippi from the widespread devastation that the Junta brought to the rest of the Confederacy, affording him a status as a popular hero for many. This was not entirely true, but those areas nonetheless had been the least affected by emancipation, had seen little to no confiscation, and were where slavery remained at its strongest at the end of the war. This meant that, compared with the Eastern States where hundreds of thousands of enslaved people had been freed or had freed themselves, a much larger number were still under chains when Kirby Smith surrendered, and the Union moved into his former Department. Union General Gordon Granger might have proclaimed in Texas in July that “all slaves are free,” resulting in the date still being celebrated as the “Third American Proclamation of Freedom,” but in truth the work to enforce emancipation had just begun. As Colonel Bentzoni warned, unless “slavery is broken up by the strong arm of the Government, it will continue to exist in its worst forms all law and proclamations to the contrary.”

Faced with veritable anarchy in many areas, and enduring slavery in others, the US Army had no option but to establish a strong military occupation to at last completely kill slavery and suppress the violence of the Jacquerie and the hunger of the famine. Within months, hundreds of Army outposts and Bureau agencies were established throughout the South. This was, a Union General wrote, a “general policy of ramifying these small posts through the country,” allowing loyalists to appeal to them to hear their complains, settle disputes, protect them from injustice, and punish crime. In this way, the Federal government and the freedmen developed a radically new conception of freedom and rights. Whereas Americans had traditionally seen the government as a source of tyranny, and freedom as the absence of governmental coercion, now freedom would mean the presence of the State power as an effective force. “This statist understanding of freedom as attachment to government, instead of separation from government, proved crucial in sustaining support for the occupation of the rebel states and in shaping the development of civil rights over the next decades,” writes Gregory P. Downs. “Instead of a march to freedom, with its connotations of separation from the state, freedpeople and soldiers described a walk toward government.”

Kirby Smith's Confederacy enjoyed relative peace when compared with the catastrophic collapse of the Junta

The greatest challenge the government confronted was an extensive famine the likes of which the United States had never seen, and thus was ill-equipped to handle. The Commissioner of the Freedman’s Bureau, Oliver O. Howard, a man known as the ”Christian General” for his close ties to aid and missionary societies, had initially been wary of turning the Bureau into a “pauperizing agency,” believing that Federal relief was “abnormal to our system of government” and that “dependency” should not be encouraged. As a result, he had initially hoped to offer only limited rations and instead focus on encouraging the resumption of agriculture. This ethos of self-sufficiency was echoed by many Northerners, who agreed that freedmen had to “feel the spur of necessity, if it be needed to make them self-reliant, industrious and provident.” Even many Black leaders declared that they didn’t want the freedmen to just be fed and clothed by the government, but instead only wished for a chance to prove themselves. To the question “What shall we do with the Negro?” Frederick Douglass answered vehemently: “Do nothing! Give him a chance to stand on his own legs! Let him alone!”

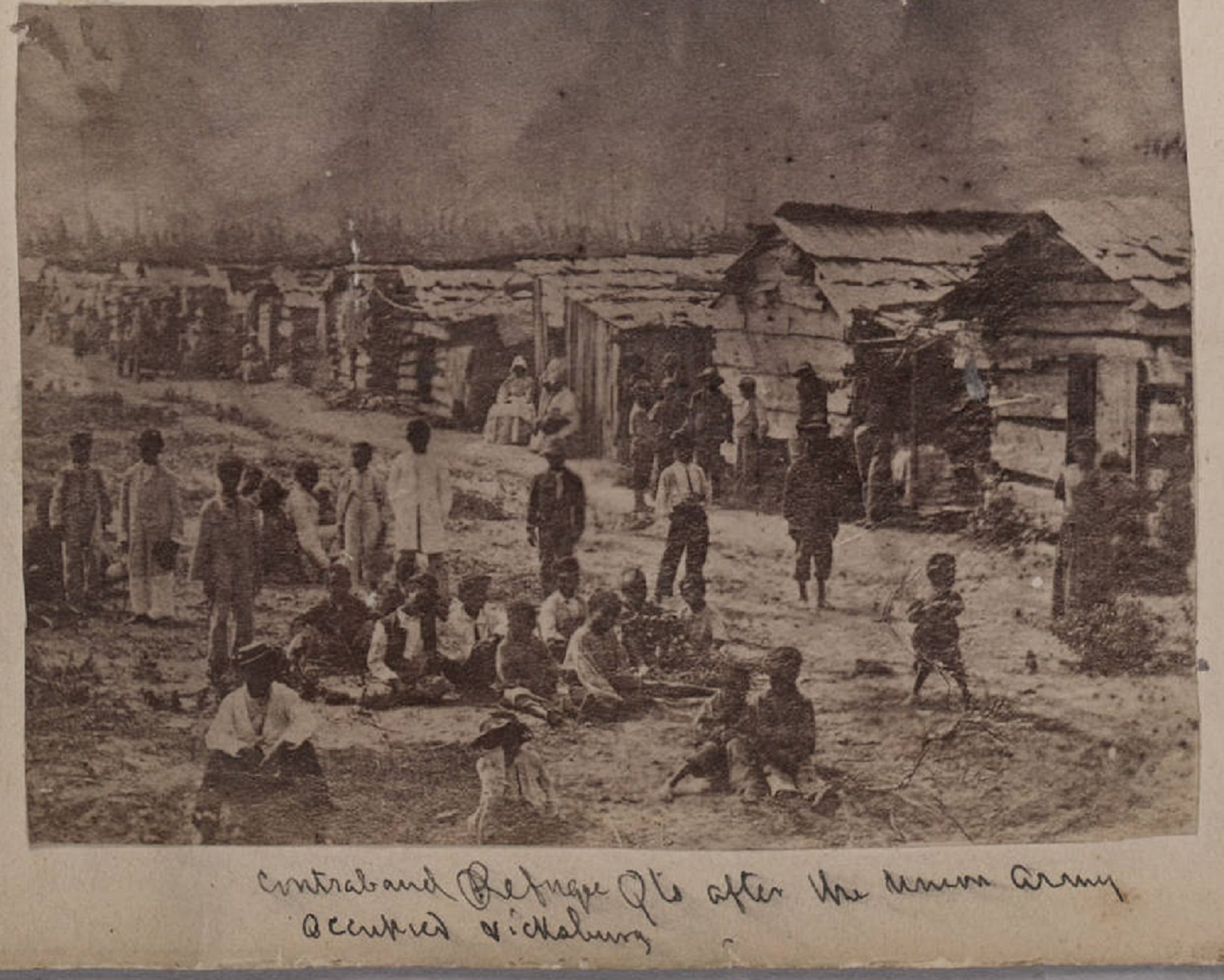

But the realities of the famine and the post-war situation soon made the Bureau and its agents realize that large-scale relief would be needed. Even when freedmen were able to start cultivating lands relatively quickly, the crops would take time to ripen. Even in Union-held areas, hunger remained widespread because foodstuffs could not be just conjured immediately. A soldier reported finding a group of freedmen “dead with green potatoes in their mouths,” in a Georgia home farm, for example. In other plantations, violence prevented food from being effectively cultivated, with freedmen being forced to flee from guerrillas to already overcrowded Union depots. The anarchic circumstances also prevented the Federals from rebuilding the Southern network of transport, and often food could only be transported to the famine-stricken countries under heavy guard, while other areas simply couldn’t be reached. Whatever subsistence remained in the countryside was easily robbed by returning veterans. Even worse, as hungry people seeking food, and fleeing loyalists seeking protection, gathered in unhygienic and cramped Bureau posts and shantytowns, epidemics of disease spread, often the only treatment available being the “root doctors and conjure men” that in truth could do little.

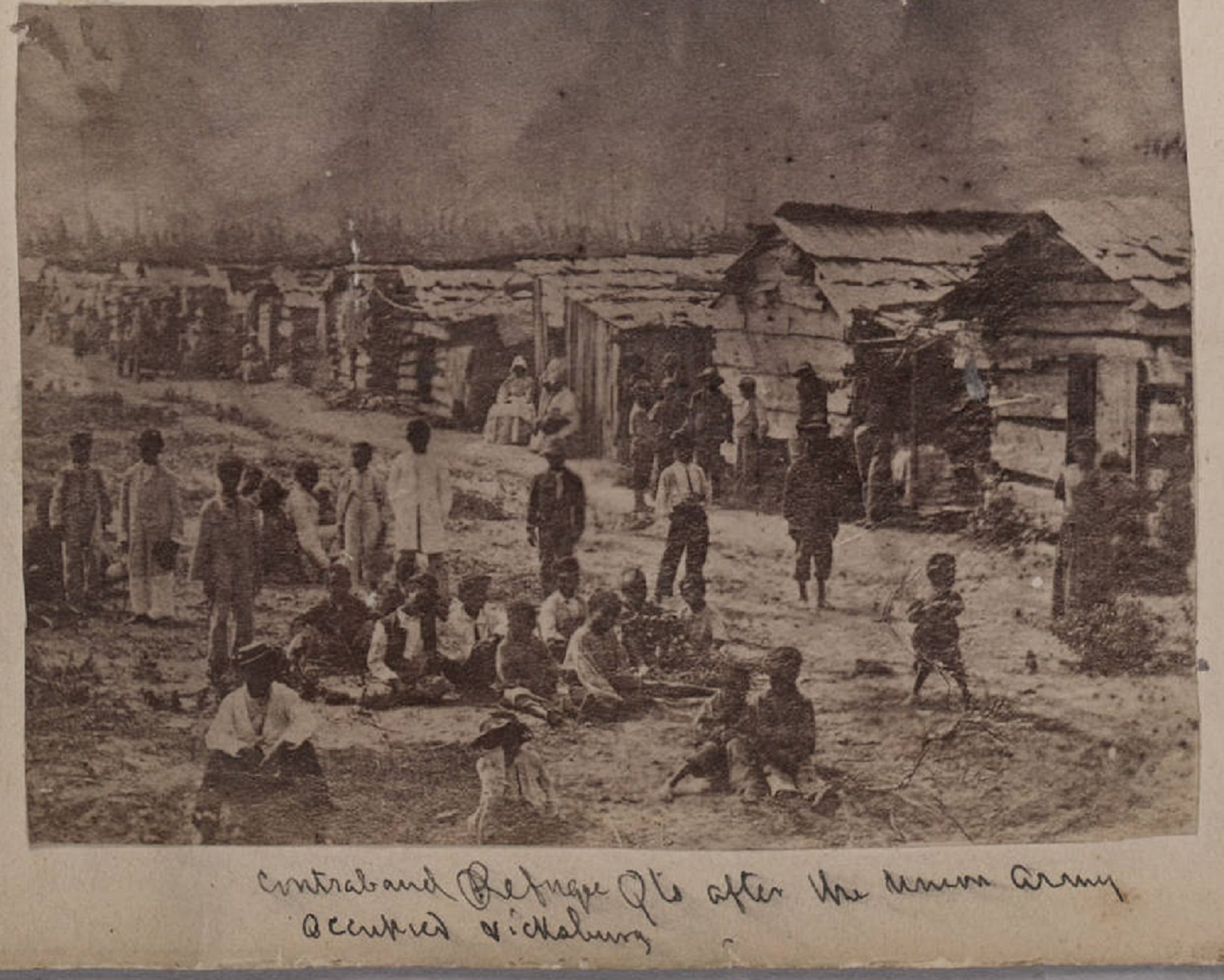

To try and end the famine, the United States government proceeded to undertake a massive bureaucratic and logistical effort that has hardly a counterpart in the 19th century. The Army and the Bureaus distributed over 20 million food rations, established schools and hospitals, rebuilt the ruined infrastructure of the South, and built refugee camps. In fact, in just a few months after the surrenders the Bureaus had built more refugee camps than during the entire war. Despite these mighty efforts, famine, epidemics, and violence still took the lives of over 600,000 Americans, divided in roughly equal numbers of Black and White civilians. Faced with such statistics, it’s easy to declare that the relief and contention efforts were just an abject failure. But it’s estimated that without this intervention, the deaths would have twice or thrice as high, and one must not ignore the truly heroic work undertaken by thousands of men and women, Black and White, to bring a minimum of safety and food security to a region so thoroughly destroyed by a bloody and long war.

One factor that further aggravated the situation was that the countryside remained in constant movement. The Civil War had produced severe dislocations throughout the South, as people fled the advancing armies, were forcibly moved by them, or poured into depots and cities for food or protection. The end of the war only increased this movement, especially by emancipated Black people. “Right off colored folks started on the move,” a Texas freedman remembered, with tens of thousands taking to the roads in what was described by hostile observers as a “vagabondage” and an “aimless migration.” In truth, this migration responded to concrete concerns, which included freedmen who had been “refugeed” or sold returning home, others abandoning White-majority areas in favor of Black population centers, and yet others trying to reach areas of land redistribution to see if they could claim a parcel for themselves.

But thousands were merely trying to reach Southern cities, where “freedom was free-er,” for there were located the Bureaus and Union soldiers that could offer a modicum of protection from the generalized violence in the rural South. A freed slave was not “safe, in his new-found freedom, nowhere out of the immediate presence of the national forces,” wrote Norfolk freedmen. As such, they were “always fleeing to the nearest Military post and seeking protection.” To try and stymie this movement, the US Army sent agents to plantation districts to teach “the colored people that they were free, they and their children, and would remain so for ever: that freedom was brought to them and they need not leave their homes to find it.” But most freedmen believed that their freedom and security was entirely dependent on the presence of US soldiers. The North Carolina freedman Ambrose Douglass would write that “I guess we musta celebrated ’mancipation about twelve time. . . . Every time a bunch of No’thern sojers would come through they would tell us we was free and we’d begin celebratin’. Before we would get through somebody else would tell us to go back to work, and we would go.”

Hastily built Bureau refugee camps

These factors all contributed to the continuance of land redistribution, a policy that instead of ending with the war only widened in scope in order to keep the freedmen in the countryside, manage the humanitarian crisis, and revive agriculture and food production. While some Northerners did advocate for using the Army to force the freedmen to sign labor contracts and to restore most land to its former owners, many were skeptical of such an approach, notably General Grant. Taught by their experience with this kind of military managed plantations in Louisiana and the Mississippi Valley, they doubted this could speedily revive agriculture and feared that it would only bring further conflict and disputes that the Army was not prepared to settle. By contrast, and with the experience of the Home Farm system in mind, they trusted Black people to farm and defend redistributed land efficiently, with less need for soldiers and Federal agents. Advocates of Free Labor were also quick to endorse the program, believing that this would prove once and for all their theory that Black free labor would be infinitely more profitable and productive than slavery had been.

Consequently, land reform advanced as mostly a practical measure, but many voices called for it as a question of justice too. The New Orleans Tribune for example advocated for extensive land redistribution in harsh terms, even saying that land should be confiscated from those who had taken the oath. "There is . . . no true republican government, unless the land and wealth in general, are distributed among the great mass of the inhabitants,” it proclaimed. "The Southern landowner's hands are red with a treason unparalleled in the world's history that no oath or pardon can wash away . . . The land tillers are entitled by a paramount right to the possession of the soil they have so long cultivated." A group of Sea Islands freedmen too addressed a letter “to our Beloved President Lincoln,” denouncing those “who were Found in rebellion against this good and just Government (and now being conquered) come with penitent hearts and beg forgiveness For past offenses and also ask if thier lands Cannot be restored to them.” “Are these rebellious Spirits to be reinstated in thier possessions?” they asked. “And we who have been abused and oppressed For many long years not to be allowed the Privilege of owning land But to be subject To the will of these large Land owners?”

In this way, land redistribution continued and deepened after the end of the war. These efforts were led by sympathetic Federal officers, such as Orlando Brown, who advocated for “extensive confiscation,” or Rufus Saxton, who told a crowd of freedmen “that they were to be put in possession of lands, upon which they might locate their families and work out for themselves a living and respectability.” General Howard himself, a friend reported, “says he will give the freedmen protection, land and schools, as far and as fast as he can.” Under military auspices, several orders dividing plantations in 40-acres plots and allocating them to Black families were produced. In fact, over 3/4th of all the land redistributed during Reconstruction was redistributed after the Confederate surrenders. In this effort they were supported by Northern Radicals, who saw in confiscation and land reform a vision for a new South of free labor, the power of its old landed aristocracy permanently broken. “My dream,” one declared, “is of a model republic, extending equal protection and rights to all men . . . The wilderness shall vanish, the church and school-house will appear . . . the whole land will revive under the magic touch of free labor.”

It must be acknowledged, however, that land redistribution never matched the dreams of many, for a substantial percentage of land remained in the hands of planters who had taken the oath or was bought by Northern factors. It also was largely unequal, with scarce land redistribution in the Upper South, areas of the Mississippi Valley and Louisiana, and the Trans-Mississippi, while a veritable “revolution of land titles” came to Alabama, Georgia, the Carolinas, and Virginia. Nonetheless, extensive land reform had granted over 25 million acres of land to over 400,000 Black families, meaning that more than a third of Black families became landowners as a result of the Second American Revolution. Moreover, some 50 million more acres came to be owned by Black people by the end of Reconstruction, bought by veterans with their bounties, cooperatives for the acquisition of land, and upwardly mobile workers. By the end of Reconstruction, 3/4ths of Black families were landowners. This was an astounding social and economic transformation that has few parallels in the history of the world.

Land reform in the Reconstructed South

It was within this context that new aspirations and demands for the post-war world were being fashioned. Much attention has been dedicated to the campaign in favor of universal Black suffrage that started around the 1864 Presidential election, chiefly spearheaded by Louisiana’s Black population. But such goals as equal rights or universal suffrage were for the most part urban concerns, the rural population being more focused on the immediate issues of land and labor. Radicals like James M. Ashley might have declared that “If I were a black man, with the chains just stricken from my limbs . . . and you should offer me the ballot, or a cabin and forty acres of cotton land, I would take the ballot.” But when one Louisiana freedman was actually asked about voting qualifications, he snapped back that “I cant eats a ballot, so I don’t want no ballot. What us wants is lands to grow food for our families.” Nonetheless, the mobilization of Black communities was also felt in the countryside, and as urban Black leaders came to recognize their need to ally with rural Black freedmen, they also started to advocate for their interests.

Initially, urban Black populations, particularly New Orleans’ gens de couleur, had sought to separate themselves from the rural freedmen. But they endured bitter experiences with the Reconstructed Government of Louisiana, which had only begrudgingly accepted a “Quadroon Bill” providing for limited Black suffrage and had made no appropriations for Black education or provided for civil equality or access to offices. In the face of this enduring discrimination, the free and the freed Black populations came to realize that they needed to unite to press for their rights. “These two populations, equally rejected and deprived of their rights, cannot be well estranged from one another,” the New Orleans Tribune wrote. “The emancipated will find, in the old freemen, friends ready to guide them . . . The freemen will find in the recently liberated slaves a mass to uphold them.” Compared with the war-time mobilizations, the conventions and meetings that took place after the end of the war took care to include the concerns of rural freedmen. The Equal Rights Convention that assembled in New Orleans had, for example, “the rich and the poor, the literate and educated man and the country laborer hardly released from bondage” sitting “side by side.” This was the start of a wide mobilization of Black people throughout the South that would greatly shape the process of political Reconstruction.

It was in this way and under these circumstances that the Black people of the Southern States claimed and defended their freedom, obtained lands to till, and started to organize to demand their rights before the Reconstructed regimes and the Federal government. Having successfully helped to defeat the Confederacy through their second front at its very heart, the enslaved also suffered greatly from the Jacquerie and the famine, events that for a long time were considered to have been White rural affairs. They, nonetheless, managed to assert their freedom, and seize plantations for their own use, which provided a strong foundation for the formal land reform that would later take place. Consequently, Black people played a vital role not as mere subjects of Federal policy, but also as active players in the end of the Confederacy and the on-going Second American Revolution, shaping the end of the war and the first months of occupation. It was on these foundations of land reform, a Statist conception of rights, and Black political mobilization that the new Reconstructed States would be built.

Last edited:

As they said in the Middle Ages, city air makes one free.But thousands were merely trying to reach Southern cities, where “freedom was free-er,” for there were located the Bureaus and Union soldiers that could offer a modicum of protection from the generalized violence in the rural South.

Hope you enjoy the chapter! The main difficulty I will face writing this thing is that there's just so much stuff going on at the same time, and I can't analyze it as once. We'll get to all other subjects in due time, for now I wanted to focus on how the last remnants of slavery were destroyed, the Black experience during the last months of the war, and the foundations for future land reform. As a note, the 25 million acres that were outright redistributed do NOT represent the totality of confiscated land. Millions of acres more were instead sold or leased, or redistributed to White yeomen, or given as bounties to soldiers, or are in the hands of the Federals who want to sell them to make a profit. So be assured that the planters lost much more land than that. Moreover, note that I wrote Black families, and given an average of four people per household that means that around 1.6 million former slaves now live on land of their own - and a substantial number are not in OTL's sharecropping contracts but more advantageous leasing arrangements that has more opportunities for obtaining land. Also, this is not the end of land reform, but the start. We will have to explore later the economics of freedom, how they fare as independent farmers and what's life like for the people who still have to work in plantations later. Next update we'll turn to the White experience, with a focus on the treason trials. So, prepare for a whole slate of mostly economic and social (alternate) history before we delve into the political reorganization of the rebel states.

@Red_Galiray Amazing work! And yes! Military occupation to enforce the New laws!

The first steps towards a better United States are beign taken!

The first steps towards a better United States are beign taken!

Can't wait for them! You're the best!Hope you enjoy the chapter! The main difficulty I will face writing this thing is that there's just so much stuff going on at the same time, and I can't analyze it as once. We'll get to all other subjects in due time, for now I wanted to focus on how the last remnants of slavery were destroyed, the Black experience during the last months of the war, and the foundations for future land reform. As a note, the 25 million acres that were outright redistributed do NOT represent the totality of confiscated land. Millions of acres more were instead sold or leased, or redistributed to White yeomen, or given as bounties to soldiers, or are in the hands of the Federals who want to sell them to make a profit. So be assured that the planters lost much more land than that. Moreover, note that I wrote Black families, and given an average of four people per household that means that around 1.6 million former slaves now live on land of their own - and a substantial number are not in OTL's sharecropping contracts but more advantageous leasing arrangements that has more opportunities for obtaining land. Also, this is not the end of land reform, but the start. We will have to explore later the economics of freedom, how they fare as independent farmers and what's life like for the people who still have to work in plantations later. Next update we'll turn to the White experience, with a focus on the treason trials. So, prepare for a whole slate of mostly economic and social (alternate) history before we delve into the political reorganization of the rebel states.

Good chapter, nice to see successful land distribution among the black populace with the collapse of the Confederacy. I can already see the books/films/shows having tales black managed towns having fending for themselves against the savage hordes of evil white planters. Keep up the good work.

Good update! We've seen the better conditions of the freedman vs. OTL building up in the ACW. Now, it's time to develop and actually defend those developments. I assume that more home farms will be formed along with their defending regiments. I'm sure there's plenty of discarded small arms from both the Federal and rebel armies to give around. Speaking of which, what will be done with home farm regiments? Will they later perhaps be reclassified as National Guard to ensure the army's numbers stay below the cap set by Congress?

That's a good starting number - IIRC W.E.B. Du Bois once estimated that the freedmen needed 25-50 million acres if they were to become independent peasant farmers. With better leasing conditions, their starting situation is better than OTL. One aspect that I considered was the conflict between farmers and merchants. IOTL since the South's banking sector was utterly destroyed due to its support of the Confederacy, farmers had to rely on merchants for both crops and credit. Maybe this is what the Freedman's Bank can be repurposed to later. On another note, there's bound to be a bit of hardship over the droughts in 1866-67 - on the other hand, if less cotton and more food was planted, there might be less hardship vs. IOTL.25 million acres

The Treason trials will be very interesting to see. IOTL the Federals ultimately buckled on concerns that the Southern jury will acquit people like Jeff Davis. IIRC, it's been mentioned that were tried by military court, which practically guarantees the sentence. That said, the use of military courts will be divisive - there will be cries of despotism while even Republicans will express concerns that this sets a precedent for engineering a 'right' outcome for a trial. That said, I'll definitely be curious to see the Southern reaction to their leaders being hung. IOTL Jeff Davis got a big popularity boost despite being hated toward the end of the war. With the break down of order in the South, I see it being less likely, though it would inflame the diehards that have so far escaped engagement with Federal authorities.Next update we'll turn to the White experience, with a focus on the treason trials.

great one. Can't wait for the nextChapter 2: We Are Bound for Freedom's Light

Emancipation and Land Reform in the last months of the war and at the start of the Military Occupation

Slavery in the United States did not end with the Emancipation Proclamation of July 4, 1862, nor did it end with the final victory over the Confederacy. Instead, and despite the celebrations of Northerners who declared that “slavery and treason are buried in the same grave,” it would take some months more before the 13th amendment was ratified and slavery was ended as a legal institution throughout the nation. But to proclaim the enslaved free did not make them so. Instead, the soldiers of the United States and the enslaved people themselves would have to enforce this freedom, ending slavery as an actual practice and claiming meaningful freedom. The work of emancipation that had started during the war continued through the collapse of the Confederacy, the bloody Jacquerie, and the anarchic situation in the immediate aftermath of the rebel surrenders. And then, after this freedom was secured, new questions regarding its meaning and boundaries had to be confronted. “Verily,” Frederick Douglass declared, “the work does not end with the abolition of slavery, but only begins.”

The continuous war-time erosion of the Confederate State and its power to violently enforce slavery had allowed the enslaved growing opportunities to challenge their masters and claim their freedom. For most of the war, this meant escaping to the Yankee lines. But this could hardly free every slave. Though the Union Armies penetrated deep into Dixie, the path they traced didn’t take them through every plantation in the South. The enslaved found by the advancing Federals would be freed, but most of the time the priority for the armies was to seize strategic cities and infrastructure and keep the enemy in check. Rarely did the Union Armies seek to establish a strong presence in the entire countryside that could free every enslaved person in a given area, for military realities required concentrating against the rebel armies and guarding key points. Consequently, even at the end of the war, a majority of the enslaved had remained in farms and plantations that hadn’t even seen a Yankee soldier during the entire conflict. For all actual purposes, they still hadn’t been freed, notwithstanding all laws and proclamations to the contrary.

While the image of the valiant Black slave defying the planters and escaping to Union lines to fight for the cause of freedom would become ingrained in the consciousness of the Black community and American popular memory, in truth, practical realities kept most Black men from escaping. Of the over 300,000 Black Union soldiers, half came from the Border States and the North, being men who had been free before the war or faced less danger in escaping slavery because they lived in Union-controlled territory. Of the other half, a large percentage were men who had been freed by the arrival of the Federals, rather than by escaping to their lines. Escaping during the war presented great peril, for right until its very collapse the Confederate government kept a strong enough grip over the population it enslaved, being able to capture and severely punish runaways, with whippings, mutilation, or execution. Escape, moreover, would mean leaving relatives and loved ones behind to the tender mercies of the slaveholders, many of whom had openly promised stern punishment to the families of escapees. Taking them along many times wasn’t an option either, for flight exposed them to many dangers such as disease, starvation, exhaustion, or slave patrols, which children or the elderly could very well not survive.

This meant that, even as it steadily and fatally wrecked slavery as an institution, military emancipation by itself failed to completely destroy it. A large number of slaveholders, for example, successfully “refugeed” their human chattel, moving them away from areas threatened by Yankee invasion to the interior or the Trans-Mississippi. Many others, even those near the Federal lines, failed in their efforts to escape, being stopped by Confederate militias. Some never tried, recognizing the dangers they would put themselves and their loves ones in. “Like everybody else, slaves were driven by a complex mixture of incentives and calculations,” writes historian James Oakes. “It cannot have been obvious to all slaves that they should quit their families, neighbors, or homes in exchange for a filthy, overcrowded contraband camp, or the brutal uncertainties of trailing an army on the march.”

It's estimated that, of around four million Black slaves, only one million had been effectively freed by the war's end

Unsympathetic Yankees were quick to assume this reluctance to escape was a sign of loyalty to the masters, or cowardice on the part of the slaves. “Not one nigger in ten wants to run off,” General Sherman complained while stationed in Tennessee. In truth, most probably wanted to flee, but just couldn’t, with a great majority of the enslaved having no option but to stay in their plantations. Even the famously destructive “marches” through Alabama, Georgia, and the Carolinas towards the end of the war were unable to completely free every single slave. “The Yankees swept through plantation districts like a tornado, destroying deserted farms and uprooting slavery along the way,” comments James Oakes. “Like a tornado, though, the severity of the damage ended abruptly at the edge of the storm’s track.” Of some 460,000 enslaved people in Georgia before the war, Sherman’s march only freed around ten thousand; of over 400,000 slaves in South Carolina, only 7,000 were directly liberated during his Carolinas campaign. Oakes concludes: “In the most concerted attack on slavery during the most deliberately destructive campaign of the war, Sherman had dislodged only about 2 percent of the slaves in Georgia and South Carolina.”

Nonetheless, the collapse of Confederate public authority and the retreat of rebel forces from many plantation districts allowed Black people to self-emancipate, seize plantations, and even organize rudimentary governments in the absence of Federal power. Sherman’s and McPherson’s marches through Alabama, as in their future campaigns, freed only a small percentage of the enslaved directly, but because they destroyed the authority of the slaveholders they found themselves unable to enforce slavery anymore. Throughout the State, former slaves declared themselves free, refusing to obey orders anymore, and even seizing lands and property. In one plantation, for example, freedmen told the former owner that “they will git the crop let them work you cant drive them off for this land don’t Bee long to you.” Whenever planters fled or were imprisoned, freedmen were quick to take control. In one plantation they drove away the overseer and declared that “they will not allow any white man to put his foot on it;” in another, the former master fled after he observed the laborers refused to work for him, the only work they completed being the construction of a gallows.

This meant that instead of the formal bureaucratic process Northerners had envisioned, land redistribution on the ground advanced informally and irregularly, with Federals often finding that the freedmen had already seized and divided the lands themselves. “I don’t do any distribution,” a Land Bureau agent wrote. “I only take note of what the negroes did already.” Often, soldiers and agents on the field encouraged defiance and fanned hopes for land redistribution. A group of self-described “loyal planters” thus complained bitterly of “negroes led astray by designing persons” who made them believe that “the plantations and everything on them belonged to them.” One example was the freedman West Turner, who was asked if he had been whipped by a Union soldier. He was, Turner answered, at least 39 times. The soldier then advised Turner to take an acre for every stroke, plus one more as a bonus, so Turner “measure off best I could forty acres of dat corn field.” Black soldiers were especially conspicuous in this regard, their mere presence encouraging the dreams of the freedmen. “The Negro Soldiery here,” a Mississippi planter said, “are constantly telling our negroes that for the next year, the Government will give them land, provisions, and Stock and all things necessary to carry on business for themselves.”

Not even declarations of loyalty could stop lands from being forcibly taken. Much to the consternation and horror of many planters, the Land Bureau allowed freedmen to testify as to the loyalty of their former owners in order to determine whether the land should be confiscated. Often, lands were taken before the owner even had an opportunity to take the oath, presenting the Federal agents with a mere fait accompli that would then be ratified after the freedmen declared the owners to have been rebels. One conservative agent at least did question “why we hear the negroes, who have a vested interest in saying their masters were the worst rebels and so to take the land.” But the Federals were reluctant to believe planters that “only remember their love for the government once they see our soldiers at their doorstep,” as a soldier said sardonically. Informed of military orders and Bureau decisions by the grapevine telegraph, freedmen were also quick to appeal to them to justify their actions. The leader of a Home Farm, for example, told the returning planter that “Massa Sherman has said that the land belongs to us the colored people,” and as such the plantation was no longer his property.

Unable to call on rebel soldiers to enforce slavery, and with the Federals proclaiming freedom and often upholding land redistribution, the slaveholders had no other option but to acknowledge the end of slavery. But in areas outside Union control where they could still count on Confederate units or local militias to impose their will, the masters grew more brutal in their methods. Frightened by news of planters who had lost their lands and by exaggerated reports of massacres, the repression faced by the enslaved only increased in the last year of the war and especially after the Coup. Under the auspices of the Southern Junta, more ruthless than Breckinridge had ever been, any sign of defiance or resistance was swiftly crushed, by such methods as publicly hanging corpses or placing the heads of runaways on pikes. Believing that “the roar of a single cannon of the Federals would make them frantic-savage cutthroats and incendiaries,” as James H. Hammond said, the planters just stepped up their campaign of terror.

The Jacquerie allowed Black people to claim their freedom and seize plantations

The power of the Confederate State and thus slavery itself started to unravel in the winter when hunger and dissent spread throughout the Southern countryside. In the areas still under Confederate control, the enslaved were usually the first victims of famine, for the enslavers preferred to keep the food for themselves, or even to sell at marked-up prices. The slaves of Charles Manigault’s plantations, for example, had been surviving in meager rice rations, and when the Federals finally freed them close to half had already died by starvation, disease, and malnutrition – which resulted in Manigault being imprisoned, for he still had beef and other supplies he simply had refused to share. Outright violence from the enslaved, heretofore, had been contained by the knowledge that insurrection had bleak odds of success and that bloody punishment would be quick to follow failure, and by hopes that the Federals would soon arrive. But driven by desperate hunger, and with organized Confederate forces dissolving and thus unable to “restore order,” enslaved people in plantation after plantation started to raise up, seizing food stores, driving away owners and overseers, and taking the plantations for themselves.

During the secession crisis, Northerners had repeatedly warned Southerners that “disunion is abolition,” for, as William Seward said, the “ferocious African slave population” could not be expected to “remain stupid and idle spectators” in the middle of a “flagrant civil war,” but would claim their freedom – by violence, if needed. The Springfield Republican likewise apprised Southerners that, once outside the Union, slavery’s “life will be one of constant peril and strife, and, like all great criminals, it will be pretty certain to come to a violent and bloody end.” Such prophecies seemed to finally be fulfilled during the Southern Jacquerie. In the Alabama and Georgia plantation districts, “perfect anarchy and rebellion” reigned, with scores of manorial houses being plundered and torched. At Middleton Place near Charleston, the freedmen even broke into the family graveyard and scattered the bones of previous slavers on the ground. Another South Carolina planter was lynched after he refused to turn the plantation over to his slaves, “his head being split open by blows with a hatchet, and penetrated by shots at his face.” James Hammond’s fears were proven correct when he, too, was murdered by the people he enslaved, who hung up his mangled corpse and danced in circles around it, chanting “I free, I free, I free!”

Hard statistics are hard to come by, muddled as they are by fragmentary reports, wild exaggerations, and untrustworthy rumors, but tens of thousands of slaves freed themselves and seized plantations during the last months of the war and its immediate aftermath. Unlike what some panicking masters declared, however, the Black insurrections did not constitute a “generalized and savage Saint Domingue,” where every White person was murdered. Masters and overseers were usually merely expelled, while there are almost no verified reports of murdered White women or children. The Southern Junta did try to repress the slave insurrections, but as their government crashed down, they simply found themselves unable to do so, especially when poor Whites were also revolting and bread riots engulfed all major cities, including Richmond. The task of restoring order instead fell on the Federals, who could, unfortunately, do little until they were able to establish an actual presence in the areas rocked by the Jacquerie. The most they could do at first was informing freedmen that “any act of violence except for those conducted in strict self-defense,” would be punished, something that may have disincentivized revenge.

Once Yankee boots actually reached the areas in upheaval, they would try to bring in food relief, suppress violence, and settle questions of land and labor. But during the initial chaotic months, decisions could be highly arbitrary, depending more on the personal biases and opinions of the officers on the field than on settled national policy. Some racist officers were prone to believe planters that painted the freedmen as bloodthirsty savages and would thus seek to violently quell insurrection. In North Carolina, one even copied the methods of the Slave Patrols and publicly hung the corpses of three Black men executed for rape and murder. Other officers, however, were more likely to imprison overseers and planters than help them recover their plantations. The paramount concern, however, was allowing for the quick resumption of food cultivation by permitting the freedmen to farm the lands they had seized, all in order to alleviate the famine. “Questions of legality and loyalty,” a Colonel informed a planter who avowed himself loyal, “shall be decided later.”

The Federal actions encouraged the freedmen, who came to believe that the Yankees had already declared the land to be theirs, and thus that when they forcibly took plantations, they were only claiming their own property. When the Federals finally took Richmond, a Black man warned his former owner that “there was to be no more master and mistress now, all was equal . . . all the land belongs to the Yankees now and they gwine divide it out among the coloured people.” A Mississippi slave also testified that “There were a heap of talk about the Yankees a-giving every Nigger forty acres and a mule. I don't know how us come to hear about it. It just kind of got around. I picked out my parcel. All of us did.” Examining the issue, General Rufus Saxton concluded that “Our own acts of Congress and particularly General Sherman’s order, which was extensively circulated among them, further strengthened them in this dearest wish of their heart—that they were to have homesteads.”

"Emancipation at gunpoint" - to enforce emancipation against rebels who clung to slavery, the US Army had to establish an effective presence in the Southern countryside

However, the freedmen’s possession of the land could prove precarious in the face of continued White resistance and terrorism. For example, after St John’s Berkley Parish in South Carolina was occupied by Black Union troops, the newly freed people took control of several plantations, only to be then attacked by Confederate scouts, who proceeded to hang their leaders and force them to work. Such violence continued well after the organized rebel forces surrendered, with returning Confederate veterans and planters forming militias to try and resist land redistribution and subjugate the freedmen to their will. Describing “rebel savagery,” a Bureau agent said that a group of returning soldiers “took some Freedmen and cut off their ears . . . now and again they ride through the country, using necklaces made with these ears.” Refusing to recognize the end of slavery, much less land redistribution, planters engaged in appalling violence to assert their control. “I saw white men whipping colored men just the same as they did before the war,” claimed the freedman Henry Adams. A guerrilla in Edisto Island, off the South Carolina coast, massacred dozens of slaves after they refused to return the land to the planters.

Such violence was distressingly commonplace in the localities most affected by the Jacquerie and the famine, where a continuous and bloody struggle over food and land continued to rage. But slavery also endured in other areas less affected by the war, where “masters kept some slaves in chains well after the Confederacy’s collapse,” Bruce Levine explains, merely informing “their laborers that nothing had changed.” In Georgia, an African Methodist Episcopal missionary found that as late as August “the people do not know really that they are free, and if they do, their surroundings are such that they would fear to speak of it.” In the same state, a young girl named Charity Austeen remembered how “Boss tole us we were still slaves. We stayed there another year until we finally found out we were free and left.” In Arkansas, the exasperated Colonel Charles Bentzoni found “slavery everywhere;” in Texas, the former masters wanted to ensure that “slavery in some form will continue to exist” by terrorizing their former slaves into obedience, and as late as October there were reports of Black people being “bought and sold as in former years.”

It's no coincidence that most of these reports come from Eastern Arkansas, Texas, and other areas of the Confederate Trans-Mississippi. Separated from the rest of the Confederacy by Grant’s capture of Vicksburg, the Department of the Trans-Mississippi had spent the latter half of the war under the military but also political and economic control of General Kirby Smith. Having refused to recognize the authority of the Southern Junta, Kirby Smith became basically a warlord, controlling his extensive Department and answering to no superior authority. The “Kirby Smith Kingdom,” as it came to be known, remained relatively stable, seeing neither large scale Union invasions, destructive military campaigns, or widespread guerrilla warfare. This is not to say that the Department was in a good condition, for its economic situation was nothing short of calamitous, especially after the Federals closed the illicit trade with Mexico. A Federal officer noted for example that “the people have neither seed, corn, nor bread, or the mills to grind the corn if they had it.” Nor did Smith manage to completely preserve slavery, for it suffered from the same erosion that affected it in the rest of the Confederacy. But compared with the Eastern States that descended into the Jacquerie and famine, the Trans-Mississippi lived relative peace, saw little destruction, and was not affected by hunger or insurrections.