I suppose, but the conscious reminder is always encouragingI can only speak for me but beside my own fun and enjoyment ain't this why we write publicly in general? ;D

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

A House Divided Against Itself: An 1860 Election Timeline

- Thread starter TheRockofChickamauga

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 67 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

XLVIII: March on Managua XLIX: The Road to Groveton XLX: The Groveton Races Groveton Order of Battles Maps for the Battle of Groveton XLXI: Once More Unto The Breach, Dear Friends, Once More Map for the Battle of Warrenton XLXII: Their Souls Are Rolling On!I'd just like to thank @GladstonianLiberal and @EarthmanNoEarth for the nominating and seconding on this TL for the 2023 Turtledoves! I'm honored to be considered for this award.

Ooh, is there a link to the Turledoves anywhere? I'd love to check em out.I'd just like to thank @GladstonianLiberal and @EarthmanNoEarth for the nominating and seconding on this TL for the 2023 Turtledoves! I'm honored to be considered for this award.

The threads for the individual awards are pinned in the relevant forums and I believe a full explanation of the event is pinned in the nonpolitical chat forum.Ooh, is there a link to the Turledoves anywhere? I'd love to check em out.

Cool, I'll check it out!The threads for the individual awards are pinned in the relevant forums and I believe a full explanation of the event is pinned in the nonpolitical chat forum.

Ooh, is there a link to the Turledoves anywhere? I'd love to check em out.

Yep, the Turtledove threads should be pinned at the top of their appropriate threads. In my particular case, it can be found here.The threads for the individual awards are pinned in the relevant forums and I believe a full explanation of the event is pinned in the nonpolitical chat forum.

I've been meaning to respond here, but just kept forgetting.

I'm happy with the route the timeline has gone, and I've found it to be going in a unique direction. Not only has the American Civil War been postponed, but Nicaragua is diverging into essentially three states inside one, leading to a tense political situation that will surly affect foreign policy and probably lead to internal war within 10 years or so.

I'm happy to have stumbled upon this timeline!

I'm happy with the route the timeline has gone, and I've found it to be going in a unique direction. Not only has the American Civil War been postponed, but Nicaragua is diverging into essentially three states inside one, leading to a tense political situation that will surly affect foreign policy and probably lead to internal war within 10 years or so.

I'm happy to have stumbled upon this timeline!

I'm always glad to hear the positive feedback from you, as it were your TLs that first inspired me to join this site and you have been very generous in helping me become a member of the community.I've been meaning to respond here, but just kept forgetting.

I'm happy with the route the timeline has gone, and I've found it to be going in a unique direction. Not only has the American Civil War been postponed, but Nicaragua is diverging into essentially three states inside one, leading to a tense political situation that will surly affect foreign policy and probably lead to internal war within 10 years or so.

I'm happy to have stumbled upon this timeline!

XLIX: The Road to Groveton

XLIX: The Road to Groveton

With the outbreak of open conflict between the two sides at the Battle of Savannah Shore, Morton's administration began to feel a renewed pressure to finally launch a full offensive against the Confederacy. Up until this point, Morton and his top military advisers had been focusing on rushing the 20,000 regular army soldiers alongside the initial 20,000 volunteers to the most crucial points of defense across the border while awaiting the proper organization and training of the tens of thousands of more troops they had called for following his inauguration. Although there were no shortage of men willing to be counted among Morton's "100,000 volunteers", Scott, Wool, and others senior military officers warned that they might no be ready to brought into a campaign until July at the earliest (and even then in a very green state). Thus, Morton throughout the months of March through June had to content himself with receiving reports from the states on the progress of their recruitment efforts as well as intelligence concerning the Confederacy's. During this period, only one major action would occur.

With Washington D.C. straddling the border with Virginia along the Potomac River, many advised Morton that it might be wise to attempt to seize the city of Alexandria across from it in Virginia. They argued that not only would it proved a buffer-zone between the capital and the Confederacy, but that it could also serve very well as a bridgehead from which subsequent Union advances into Virginia could occur. Hoping to inspire national morale and prove to both national and foreign onlookers that his government had force behind it, Morton agreed to the effort. Taking six thousand of the original volunteers, alongside two thousand regular army soldiers, Morton would give the command to Brigadier General Thomas. Organizing his eight regiments into two brigades under newly promoted brigadier generals William S. Rosecrans and Henry W. Slocum, Thomas would secure the necessary transports and supplies and prepare for the effort to begin on April 15.

Early on the morning of that day, Thomas and his forces would board the vessels and cross the Potomac River. Accompanied by several gunboats under the command of Captain Samuel F. DuPont, the Union forces would find the defenses of the opposing shore surprisingly quiet. Directing the landing in person, Thomas would find several abandoned artillery emplacements, and as the Union troops marched through the city they found no organized opposition. Surprised but satisfied with his bloodless triumph, Thomas would join Rosecrans and Slocum in securing the premises of the city. Meanwhile, one of the most iconic images of the war would occur when Colonel Elmer Ellsworth, leader of one of the volunteer regiments, would climb to the top of one of the city's hotels and replace its Confederate flag with a Union standard. Already somewhat of a celebrity around the nation for his pre-war military units, Ellsworth would become the first soldier in the American Civil War to win a Medal of Honor for his act on May 28, 1865.

An envelope honoring the actions of Ellsworth in the capture of Alexandria

In spite of basking in the glory of the hour, both Morton and Thomas were perplexed by the events of the day. They had received credible reports of at least 1,000 Confederates in the defense of the city, and the cannons found in its shoreline defenses confirmed that they had been there. From those pieces being left behind, Thomas speculated that word must have leaked to those Confederates of the impending Union advance against them, leading to their hasty retreat during the night. From this, rumors began to swirl of a spy in the Union capital who had been leaking information to the enemy. Being so close to the South both geographically and culturally, it proved difficult to ascertain exactly who was the spy, however. It might have continued for much longer had the Union not chanced upon a lucky break while investigating Confederate headquarters in Alexandria. In the haste of the evacuation, the commander of the Confederate military defenses, Colonel Richard S. Ewell, had left several of his papers behind. Among these was a letter from Rose O'Neal Greenhow, which provided information concerning the upcoming Union advance. Greenhow, a Washington socialite, was noted for his connections among Washington's governing class as well as for suspect sympathies. With the letter in hand, Morton quickly had her arrested and prevented from further correspondence with the enemy.

With the momentary crisis abated, all eyes turned once more upon the upcoming campaign. Following his success in Alexandria, Thomas would be given a promotion to major general in both the volunteer and regular army. As a result of this, Winfield Scott would announce his retirement from the position of Commanding General of the United States Army. He had been contemplating the move ever since the outbreak of civil war, but wanted to see to it that a man he approved of succeeded him. With Thomas' success and promotion, he believed the time had come, and announced him as his preferred successor. Morton and Congress would oblige him, making Thomas the 4th Commanding General of the United States Army. Not all was to be triumph for Thomas in the realm of politics, however. Although Congress had been content to laud him with promotion and positions, there were many also who were not particularly comfortable with the idea of the Virginian being given the top command in an invasion of his home state. Sensing the political reality, Morton began approaching Thomas with the prospect of command in the Western Theater. Already Thomas had been hoping to secure a position out from under the direct eye of supervision of Washington, so he eagerly would accept Morton's offer to take over efforts on that front.

This maneuvering, however, left it unclear who would head the upcoming Union invasion into Virginia. As the army began assembling around Washington and preparations needed to begin for their strategy, it became important that a man was selected to head them. Despite his good service in organization and pleading of his continued competency, Wool was considered too old to give such a large and demanding command. Of the other heroes of Alexandria, Rosecrans had already been selected by Morton to accompany Thomas west and take command of another army to conquer the Mississippi River, while Slocum's Democratic tendency were too well-known to be acceptable to the Republican-dominated Congress. The commander of Washington's defenses, Brigadier General Charles F. Smith, was briefly considered as a possibility, but his military expertise provided too invaluable to overseeing matters in the capital to deploy the field. Similar logic kept Brigadier General Henry W. Halleck in his Washington office.

Ultimately, the top command position for what would develop into the Army of the Potomac would be given to a man who had been out of the regular army for almost twelve years. Selected by Governor Edwin D. Morgan to lead a brigade of New York volunteers south on the basis of his prior military experience alongside his personality, Joseph Hooker made quite a reputation for himself once he arrived in Washington. Among the first of officers to lead troops into the city, he soon became known as among the most vocal. Noted for his grand public speeches on the sanctity of the Union and grandiose armchair strategies to restore it, the man who often had a marked ability to rub compatriots the wrong way ended up finding the right way to appeal to the most powerful Republicans. Already enjoying the favor of the powerful New York congressional delegation because of the troops under his command, he quickly became a favorite of Morton, Chandler, and the powerful senator Benjamin F. Wade as well. With this support, he soon found his way into promotions and public accolades. He would be promoted to major general in the volunteer army (making him junior only to Thomas and Rosecrans) and given a coveted brigadier commission in the regular army.

Major General Joseph Hooker

As his army's structure formed around him, Hooker began to take measures to ensure it was properly trained and supplied. Beyond that, however, he took measures to ensure that their morale was well-supported as well. Perhaps the most well-remembered examples of this (at least in the diaries of the common soldiers) was Hooker's bread ovens. Hardtack was common fare for soldiers as they marched from their training camps to the Washington encampment. Once they had arrived, however, they were in for a pleasant surprise. As one New Hampshire soldier recorded in his diary, "All that we had had to eat on the march south to face the rebel foe had been hardtack and salt pork. Uncle Joe quickly saw to this once we had arrived, and we were treated to fresh loaves from the ovens he had constructed, along with many of food stuffs that we could previously only dream of." Perhaps drawing from the famous maxim of the man he drew much military inspiration from, Hooker made sure that the stomach that his soldiers would march on would be a fully satisfied one.

As Hooker was finding success with his new command, his Confederate counterparts were in for more of a struggle. Following the bloodless but embarrassing retreat from Alexandria, President Mason had begun calling together units to defend his home state. Despite the Confederate capital being safely behind the lines in Atlanta, Mason still hoped to prevent as much carnage as possible from being brought upon his home state. To that end, he proposed that Virginia should serve as the defensive line for the Eastern Theater of the Confederacy. This was heartedly approved of by most within the Confederate government, causing them to generally be able to overcome their state's rights qualms and dispatch large numbers of their volunteer regiments to the state. Accompanying these organizations north would be General David R. Jones, who had become popular throughout the nation for his involvement in the Battle of Savannah Shore. Once he arrived in Virginia, he would be given command of a large number of the troops in the state, with the remainder being under the command of General Joseph E. Johnston, a native of the state and the senior-most American officer to join the Confederacy.

Jones would be in command of the equivalent of three corps, although they were not officially referred to as such at the time. These were commanded by James Longstreet, Theophilus H. Holmes, and D.H. Hill, who all held the rank of brigadier general as at the time it was the only grade of general beside "general" in the Confederate Army. Generally referred to as the Army of Centreville, they stay astride a connection of Alexandria to the state capital of Richmond, camping near the town of Centreville. Johnston's command, generally referred to as the Army of Fredericksburg, was posted along another more southern route to Richmond and was camped near the town of Fredericksburg. It would consist of only one equivalent corps under the command of Brigadier General Thomas J. Jackson. Technically junior to Jones in rank, Johnston's pride made him insistent upon an independent command. Jones, who generally had a gentler personality, was willing to oblige this. Mason, meanwhile, saw the value of protecting two potential routes of invasion and approved the command structure. It was understood that either force would come to the reinforcement of the other in the case of attack, but most expected Jones' Army of Centreville to be the more likely target, which led to its larger size.

General Joseph E. Johnston

With his strategy now planned, Hooker and his officers presented it to Morton for final approval. Eager to embrace any forward motion into the Confederacy, Morton signed off on the effort and gave Hooker permission to go ahead. With this, Hooker organized his command and began to ferry them across the Potomac River into Alexandria on July 16, 1865. By the next day, the Army of the Potomac had crossed its namesake river and could begin its march against Jones' Army of Centreville. The stage was set for the Battle of Groveton, and now the pieces were in motion for the first major battle of the American Civil War.

Great work as always! I usually am not a fan of Civil War timelines since how detail oriented they can get, but you do such a good job with this.

Yeah. I know how sometimes they can be hard to follow, so I'm going to try and incorporate maps and orders of battle to hopefully make this TL as understandable and accessible as possible.Great work as always! I usually am not a fan of Civil War timelines since how detail oriented they can get, but you do such a good job with this.

Regardless of his ultimate fate, Hooker is certainly about to earn his OTL nickname: Fightin' Joe Hooker.

The irrepressible conflict is upon us, and every soldier is called upon to do his duty.

I wonder if Hooker will have a better run than in OTL, or if he'll cock up and force the administration to switch him out.

XLX: The Groveton Races

XLX: The Groveton Races

As soon as Jones received reports of the advance of Hooker's troops from Washington into Alexandria, his headquarters soon devolved into a storm of panic. Immediately desperate riders were dispatched to Johnston and his Army of Fredericksburg to come immediately for his reinforcement. By the time that the Union crossing was completed on July 17, 1865, Jones knew that it was going to be a close contest over whether Hooker or Johnston would arrive first. He decided to consult his subordinates about what measures to take in response. The force of the Army of the Potomac was reportedly 75,000, while the Army of Centreville hosted around 45,000 soldiers with the Army of Fredericksburg representing an additional 15,000 men. With this reality plainly known, all three of his corps commanders urged Jones to withdraw to a stronger position behind the Bull Run Creek, both to mount a better defense and close the distance between himself and Johnston. The specifics of strategy, however, differed among the officers. Longstreet, his senior subordinate, advocated that the retreat continue until they had linked forces with Johnston (perhaps at Warrentown) and then they should turn to face Hooker. Hill and Holmes, however, argued that the Bull Run Creek would offer a better defensive line to hold out against the numerically superior Federals. They believed either that Johnston could arrive at that position even before the battle began, or that the Army of Centreville would be able to withstand long enough for him to appear shortly after the commencement of battle.

Wanting to concede as little territory to the Union as possible and fearful of the toll on morale from a prolonged retreat, Jones ultimately opted to support the latter plan. As the Army of Centreville began to leave their eponymous town on July 18, however, it seems that the high command was unaware just how close Hooker and the Army of the Potomac was. Already on the night of the day advance Union cavalry detachments were capturing stragglers from the withdrawal. As July 19 dawned, it seemed that battle was imminent. The morning saw the advancing Union column closing the distance of their retreating foe. Eventually, this would become all to clear to the Confederate high command. By 10:00 AM of that day, Jones had already withdrawn the corps of Longstreet and Hill across the Bull Run Creek, and only Holmes men remained to depart. It was then the first sightings of the Union troops occurred. Hooker's Army of the Potomac had been in a close pursuit of the Army of Centreville, marching in a column led by Hancock's II Corps, followed by Reynolds' V, Sedgwick's VI, Slocum's I, Howard's III, and Burnside's IV. The inexperienced cavalry brigade attached to Holmes' corps in the rear of the column, led by Colonel Beverly H. Robertson, failed to scout or report on the narrowing distance between the two armies.

Thus, by morning, Holmes' corps found itself positioned on one side of the Bull Run Creek with the rest of the Army of Centreville having already crossed over to the other side. A more decisive commander perhaps could have salvaged the situation by committing to one bank of the creek or the other, but instead Jones hesitated. Fearing a sudden Union strike on a disorganized column, he ordered Holmes to attempt to hold his position and engage in a fighting but organized retreat. Confronted by subordinates with the reality that Holmes' individual corps was likely be overwhelmed by itself, he still refused to immediately order his corps already across the river to march to the aid of Holmes. By the time he realized how truly dire a situation Holmes was in and attempted to send aid, it would be too late. Thus, the Battle of Groveton, the first major battle of the American Civil War, would begin in earnest.

Brigadier General Theophilus H. Holmes

Having waited for the Confederates to abandon their position, Hooker now ordered his men to charge. The eager Union volunteers quickly obliged the command. Their initial volleys devastated Holmes' tattered command, and his organized withdrawal quickly dissolved into a rout under the weight of the Union assault. The three Union corps corps closed like wings around Holmes' command. Ransom's division, which had been the center of Holmes' crescent, was almost completely enveloped as the wings of Union the advance closed the gap between them. It helped those Confederates little that Ransom lay mortally wounded from a chest wound inflicted during the Union volleys. It was at this moment of supreme chaos that Jones finally ordered Hill to advance one of his divisions under William Dorsey Pender to aid Holmes. As those men advanced toward the bridge, they were soon buffeted by the stream of hopelessly panicked Confederates, only further confusing their retreat. Sensing the situation, Pender would turn his division around and march it back to the Confederate line at Groveton to prepare for the inevitable Union assault to follow.

By high noon, the Union had solidified control over the bridge crossing the Bull Run and were eager to continue their advance. They had already smashed one of the Confederate corps and were eagerly anticipating doing that to the remaining two. Rightly suspecting that the remaining two Confederate corps had established a stronger position, Hooker would order a halt to his Union troops across the Bull Run Creek in order to reposition them to advance against them. Although a reasonable maneuver at the time, this delay of an hour would ultimately play a major role in the course of the battle. At 1:00 PM, Hooker had arranged his six infantry corps into a long line to advance. Forming the center of this would be the three corps that already seen action. Anchoring the right would be the I Corps under Henry W. Slocum, while his left would be held by III and IV Corps under Howard and Burnside respectively. Their advance against the remaining Confederates was ready to begin in earnest.

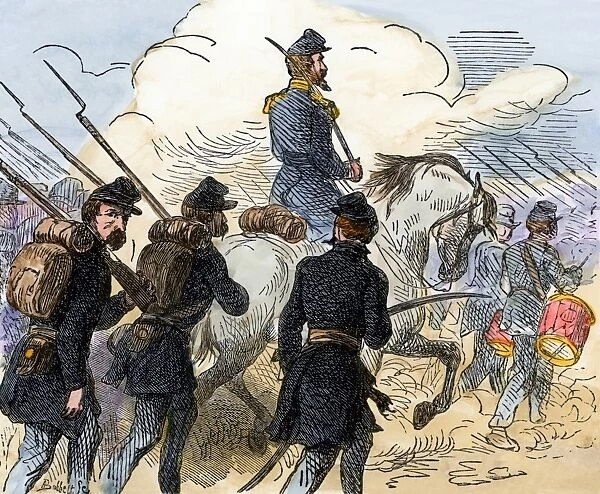

A depiction of the advance of the Union IV Corps

Once more in the vanguard would be the corps of Hancock, Reynolds, and Sedgwick. Hardly injured during their battle at Bull Run Creek and already in a fiery fervor, Hooker saw fit to unleash their determination against the main line of Jones. Hoping to once more envelope the foe, they would serve to pin Jones in his position. Slocum would work his way around the Confederate left, while Howard and Burnside acting similarly on the Confederate right. Slocum's advance was to be the diversion, causing Jones to throw whatever reserves he had available to confront him. This was to be followed by Howard and Burnside falling upon the Confederate line and rolling it up. With this strategy in place, Hooker would send the first prong of his attack forward.

As they had done before, the three Union corps unleashed their full and ferocious might against their Confederate opponents. In this case, however, they were being met by roughly even numbers and a much stronger position. In spite of all of their spark, they were soon stalemated against the Confederate front, unable to form a breach in their lines. What they were doing successfully, however, was fulfilling their role in Hooker's plan. They were hitting as hard as they were getting hit, and once more Jones' scouts failed him. He assumed that those men were the sum total of Hooker's advance, and while the fighting was fierce, his men were holding the line. A strong and unified push by Hancock's three divisions under John Gibbon, Alexander S. Webb, and Samuel S. Carroll seemed poised for a breakthrough in one frightful moment, but Longstreet was ultimately able to rebuff them. When Slocum appeared to the north of his line complete, however, panic once more gripped the nervy Jones. His response was just as Hooker envisioned, throwing whatever troops he could assemble against the threat to his left flank. Slocum's probing attacks were held back. But the final surprise was yet to drop.

At 3:30 PM, the 24,000 men of Howard and Burnside appeared on the right flank of the Army of Centreville. Already overextended and locked in inextricable combat on the front and left, Jones was seemingly bagged by Hooker's trap. It was here that Hooker's delay to reorganize his army came back to bite him. As the two Union army corps crashed into the Confederate right, all seemed lost for Jones. As the two Union corps became intermingled and jumbled, however, the Confederate salvation arrived in the form of the Army of Fredericksburg. Having intermittently rode on trains and ran on foot toward Jones' position, the Army of Fredericksburg arrived on the scene just in time to salvage the situation. At 4:00 PM, Johnston and Jackson directed their howling troops into the heart of the action. Surprised by the assault on their flank, the inexperienced troops of the III and IV Corps fell back and relieved the pressure on Jones. Seeing his last opportunity for escape, Jones ordered a full withdrawal of his troops over the path he has designated for retreat. Although by no means completely organized and unharried, as Hooker ordered Slocum to throw his corps into a full assault, the Army of Centreville managed to escape complete annihilation. Jackson's corps would be badly bloodied while serving as a rearguard, but disaster had been averted for the Confederacy.

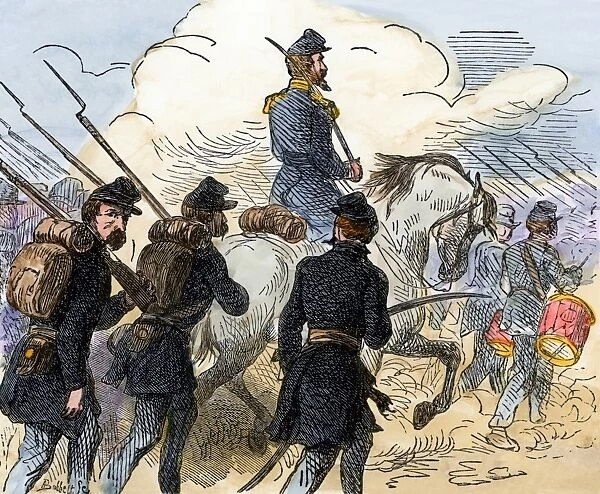

Jackson overseeing the deployment of his corps at the crucial moment

Groveton Order of Battles

Army of the Potomac

Major General Joseph Hooker, Commanding

I Corps: Major General Henry W. Slocum

1st Division: Brigadier General George Sykes

2nd Division: Brigadier General Andrew A. Humphreys

3rd Division: Brigadier General John C. Robinson

Attached Cavalry Brigade: Brigadier General Elon J. Farnsworth

II Corps: Major General Winfield S. Hancock

1st Division: Brigadier General John Gibbon

2nd Division: Brigadier General Alexander S. Webb

3rd Division: Brigadier General Samuel S. Carroll (w)

Attached Cavalry Brigade: Brigadier General John Buford

III Corps: Major General Oliver O. Howard

1st Division: Brigadier General John Newton

2nd Division: Brigadier General Orlando B. Willcox (w)

3rd Division: Brigadier General Gershom Mott

Attached Cavalry Brigade: Brigadier General George H. Chapman

IV Corps: Major General Ambrose Burnside

1st Division: Brigadier General Samuel W. Crawford

2nd Division: Brigadier General George W. Getty

3rd Division: Brigadier General Rufus King (w)

Attached Cavalry Brigade: Brigadier General George D. Bayard

V Corps: Major General John F. Reynolds

1st Division: Brigadier General Charles Griffin

2nd Division: Brigadier General David A. Russell

3rd Division: Brigadier General Lewis A. Grant

Attached Cavalry Brigade: Brigadier General William W. Averell

VI Corps: Major General John Sedgwick

1st Division: Brigadier General Christopher C. Augur

2nd Division: Brigadier General Romeyn B. Ayres

3rd Division: Brigadier General James B. Ricketts

Attached Cavalry Brigade: Brigadier General David McM. Gregg

Army of Centreville

General David R. Jones, Commanding

Longstreet's Corps: Brigadier General James Longstreet

1st Division: Brigadier General Richard H. Anderson

2nd Division: Brigadier General John B. Hood (w)

3rd Division: Brigadier General Joseph B. Kershaw

Attached Cavalry Brigade: Colonel Wade Hampton III

Hill's Corps: Brigadier General Daniel H. Hill

1st Division: Brigadier General William D. Pender

2nd Division: Brigadier General Cadmus M. Wilcox

3rd Division: Brigadier General Robert E. Rodes

Attached Cavalry Brigade: Colonel Turner Ashby

Holmes' Corps: Brigadier General Theophilus H. Holmes

1st Division: Brigadier General Gustavus W. Smith

2nd Division: Brigadier General Robert Ransom Jr. (mw)

3rd Division: Brigadier General Raleigh E. Colston

Attached Cavalry Brigade: Colonel Beverly H. Robertson

Army of Fredericksburg

General Joseph E. Johnston, Commanding

Jackson's Corps: Brigadier General Thomas J. Jackson

1st Division: Brigadier General Richard S. Ewell

2nd Division: Brigadier General Ambrose P. Hill

3rd Division: Brigadier General James L. Kemper

Attached Cavalry Brigade: Colonel J.E.B. Stuart

Major General Joseph Hooker, Commanding

I Corps: Major General Henry W. Slocum

1st Division: Brigadier General George Sykes

2nd Division: Brigadier General Andrew A. Humphreys

3rd Division: Brigadier General John C. Robinson

Attached Cavalry Brigade: Brigadier General Elon J. Farnsworth

II Corps: Major General Winfield S. Hancock

1st Division: Brigadier General John Gibbon

2nd Division: Brigadier General Alexander S. Webb

3rd Division: Brigadier General Samuel S. Carroll (w)

Attached Cavalry Brigade: Brigadier General John Buford

III Corps: Major General Oliver O. Howard

1st Division: Brigadier General John Newton

2nd Division: Brigadier General Orlando B. Willcox (w)

3rd Division: Brigadier General Gershom Mott

Attached Cavalry Brigade: Brigadier General George H. Chapman

IV Corps: Major General Ambrose Burnside

1st Division: Brigadier General Samuel W. Crawford

2nd Division: Brigadier General George W. Getty

3rd Division: Brigadier General Rufus King (w)

Attached Cavalry Brigade: Brigadier General George D. Bayard

V Corps: Major General John F. Reynolds

1st Division: Brigadier General Charles Griffin

2nd Division: Brigadier General David A. Russell

3rd Division: Brigadier General Lewis A. Grant

Attached Cavalry Brigade: Brigadier General William W. Averell

VI Corps: Major General John Sedgwick

1st Division: Brigadier General Christopher C. Augur

2nd Division: Brigadier General Romeyn B. Ayres

3rd Division: Brigadier General James B. Ricketts

Attached Cavalry Brigade: Brigadier General David McM. Gregg

Army of Centreville

General David R. Jones, Commanding

Longstreet's Corps: Brigadier General James Longstreet

1st Division: Brigadier General Richard H. Anderson

2nd Division: Brigadier General John B. Hood (w)

3rd Division: Brigadier General Joseph B. Kershaw

Attached Cavalry Brigade: Colonel Wade Hampton III

Hill's Corps: Brigadier General Daniel H. Hill

1st Division: Brigadier General William D. Pender

2nd Division: Brigadier General Cadmus M. Wilcox

3rd Division: Brigadier General Robert E. Rodes

Attached Cavalry Brigade: Colonel Turner Ashby

Holmes' Corps: Brigadier General Theophilus H. Holmes

1st Division: Brigadier General Gustavus W. Smith

2nd Division: Brigadier General Robert Ransom Jr. (mw)

3rd Division: Brigadier General Raleigh E. Colston

Attached Cavalry Brigade: Colonel Beverly H. Robertson

Army of Fredericksburg

General Joseph E. Johnston, Commanding

Jackson's Corps: Brigadier General Thomas J. Jackson

1st Division: Brigadier General Richard S. Ewell

2nd Division: Brigadier General Ambrose P. Hill

3rd Division: Brigadier General James L. Kemper

Attached Cavalry Brigade: Colonel J.E.B. Stuart

Wonderful job! Also, it is always nice to see Joe Hooker do well in an Alt Civil War.

Seems like the secessionists are being handed one terrible defeat after another. At this rate, the CSA might last only a fraction as long as it did in OTL: which might be both a good and a bad thing, as the country would suffer from less bloodshed and destruction, but at the same time abolition might be once again delayed by a faster, sharper civil war.

Threadmarks

View all 67 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

XLVIII: March on Managua XLIX: The Road to Groveton XLX: The Groveton Races Groveton Order of Battles Maps for the Battle of Groveton XLXI: Once More Unto The Breach, Dear Friends, Once More Map for the Battle of Warrenton XLXII: Their Souls Are Rolling On!

Share: