Preparation for Bulgarian involvement and mobilization in WW1

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bulgaria_during_World_War_I [Actual events that occurred in reality are covered here, along with some modifications.] [This is about material that is counterfactual, except using the Wikipedia article as a source. Bulgarian mobilization is the same as reality except being approximately two months earlier and slightly faster with the Serbian defeat.]

The Bulgarian Summer of 1915

The summer [June to August] months were most critical for Bulgaria as the events that happened on the front changed drastically from the outcomes that were expected. In April-May, following the fall of Przemysl with the loss of 100000's of Austro-Hungarian troops, the Gallipoli Campaign and Italian intervention on the side of the Entente, Bulgarian negotiations with the Entente increased as it was believed there was little point in joining the losing side and getting threatened by the Entente and Russia from the Turkish border, coastline and Austro-Hungarian defeat.

The summer months of 1915 saw the decisive clash between the diplomacy of the

Entente and the

Central Powers take place. A young French historian, a reporter for the French

press and witness of the critical events named

Marcel Dunan summarized the importance of this period for the entire course of the war by simply naming it the "Bulgarian Summer" of 1915. Bulgaria's strategic geographic position and strong army now more than ever could provide a decisive advantage to the side that managed to win its support. For the Allies, Bulgaria could provide needed support to Serbia, shore up Russia’s defenses, and effectively neutralize the

Ottoman Empire while for the

Central Powers it could ensure the defeat of Serbia, cut off Russia from its allies and open the way to

Constantinople, thus securing the continuous

Ottoman war effort. Both sides had promised more or less the fulfillment of Bulgaria's national aspirations and the only problem facing the Bulgarian prime minister was how to secure maximum gains in exchange for minimum commitments.

During this time many Entente and

Central Powers dignitaries were sent to

Sofia in an effort to secure Bulgaria's friendship and support. Allied representatives met with the leaders of the Bulgarian opposition parties, they also provided generous financial support for opposition news papers and even attempted to bribe high ranking government officials.

Berlin and

Vienna were not willing to remain on the sidelines and dispatched to Bulgaria the

Duke of Mecklenburg, the former ambassador to the

Ottoman Empire Hans Freiherr von Wangenheim and the Prince Hohenlohe, who openly declared that after the defeat of Serbia, Bulgaria would take control of the Balkans and dominate the mainland of the peninsula. What kept the Bulgarian interest the most was indeed the balance of military power. The situation on the major European fronts was at that time developing markedly in favor of the

Central Powers and while the Allied operation in

Gallipoli turned into a costly stalemate the Russians were being driven out of

Galicia and

Poland. Under these circumstances, the Allies were hoping to finally secure Bulgaria, especially in the face of Italian entry and the imminent Serbian offensive.

Still, it took Entente diplomacy more than a month to give an answer to Radoslavov's questions and the reply proved far from satisfying. In reality it hardly differed from the offer the Allies presented in May. Once again the promises lacked a clear guarantee that Serbia would cede the desired lands and there was not even a mention of

Southern Dobrudja. In the eyes of the Bulgarians this was a manifestation of the Entente helplessness in the face of the conflicting ambitions of it smaller Balkan allies. The diplomatic positions of the

Central Powers in

Sofia were strengthened immensely forcing the Bulgarian tsar and prime minister to assume a course towards a final alignment of the country to the side of the

Central Powers. In August a Bulgarian military mission led by Colonel

Petar Ganchev, a former military attaché in Berlin, was dispatched to Germany to work out the details for a military convention. Almost simultaneously,Lieutenant-General Ivan Finchev resigned as minister of war for his pro-Entente sympathies and was replaced as minister by the pro-German

Major General Nikola Zhekov. Radoslavov had also entered talks with his country's despised enemy, the

Ottoman Empire, trying to gain concessions in exchange for Bulgarian benevolent neutrality. In this situation Germany,unlike the Allies, was able to persuade its ally to at least seriously consider ceding some land to gain Bulgarian support. Still the Ottomans were willing to conclude the deal only after Bulgaria entered into an agreement with the Central Powers.

Throughout the month of July, the Allied diplomatic activity was growing more incoherent. British and French diplomats began to realize that in the face of the stubborn Serbian and Greek refusals of any immediate concessions the best they could hope for was to keep Bulgaria neutral. In the face of its diplomatic failure, the

Entente even resorted toless conventional methods of keeping Bulgaria on the side lines, but it was hoped that the Serbian and Italian Offensives would suceed and encourage Romania to join the Entente, getting the Balkan Front full of activity against the Austrian southern flank and finally bringing Bulgaria on the Entente side. The Allies and their Bulgarian political sympathizers attempted to buy out the country's grain harvest and create a food crisis. This

affair however was revealed to the Bulgarian government and the perpetrators were arrested. Entente diplomats continued to pressure the Serbian government, finally forcing it to assume a more yielding attitude. On 1st of August, in the face of defeat by Austria-Hungary, Serbian prime minister Nikola Pasic agreed to cede about half of the uncontested zone but he demanded that Serbia should keep most of the land to the west of the

Vardar including the towns of

Prilep,

Ohrid and

Veles. In return for these territorial concessions, the Allied Powers had to allow Serbia to absorb Croatia and Slovenia and demand Bulgaria to invade the

Ottoman Empire, which it had just signed a treaty with in conjunction with the Suvla landings on 6 August. The Serbian offer was unacceptable and most of its demands were rejected. At the same time the Entente was unaware that the negotiations between Bulgaria and the

Central Powers had passed a critical phase and caused more trouble than worth when Bulgaria declared war in 2 weeks' time.

The decision of Serbia to maintain control of Macedonia was controversial because it sealed its doom. As Marcel Denan later stated, not only did continued Serbian control of Macedonia deprive Bulgaria of its most wanted territory, but tied up almost an entire [albeit weak] army to be destroyed when it could have ensured the success of the Serbian offensive's aims and Romanian entry, further and probably totally securing Bulgarian neutrality or Entente participation against the Ottomans and leading to success in Gallipoli, followed by a triumphant march to Constantinople with a successful landing in Suvla.

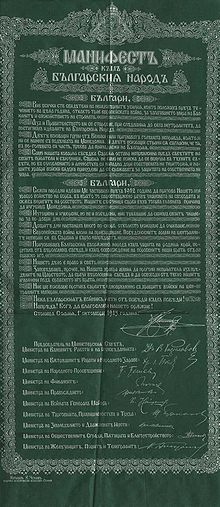

Bulgaria enters the war

On 24 July 1915, Bulgaria formalized its affiliation with the

Central Powers by concluding three separate documents of political and military character after the Serbian Offensive's defeat was confirmed. The first document was signed by prime minister Radoslavov and the German ambassador Michaheles in

Sofia and constituted the

Treaty of Amity and Alliance between the Kingdom of Bulgaria and the German Empire. It consisted of five articles that were to remain in force for five years. According to the treaty, each of the contracting sides agreed not to enter an alliance or agreement directed against the other. Germany was obliged to protect Bulgarian political independence and territorial integrity against all attack which could result without provocation on the side of Bulgaria's government. In exchange, Bulgaria was compelled to take action against any of its neighbouring states if they attacked Germany, the Ottoman Empire or Austria-Hungary such as Romania and Greece after Serbia and Entente expeditionary forces were dealt with.

The second important document the two men signed was a secret annex to the Treaty of Alliance. It specified the territorial acquisitions that Germany guaranteed to Bulgaria and included the whole of

Vardar Macedonia, including the so-called contested and uncontested zones, plus the part of Old Serbia to the east of the Morava river. In case Romania or Greece attacked Bulgaria or its allies without provocation, Germany would agree to Bulgarian annexation of the lands lost to these countries by the

Treaty of Bucharest, and to a rectification of the Bulgarian-Romanian border as delimited by the

Treaty of Berlin. In addition, Germany and Austria-Hungary guaranteed the Bulgarian government a war loan of 200,000,000 francs and in case the war lasted longer than four months, they guaranteed an additional supplementary loan.

The third documented was concluded at the German Eastern military headquarters in

Pless by the Chief of the

German General Staff Erich von Falkenhayn, the Chief of the Austro-Hungarian General Staff

Count Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf and the delegate of the Bulgarian government

Colonel Peter Ganchev. It was a military convention detailing the plan for the final defeat and conquest of Serbia. Germany and Austria-Hungary were obliged to act against Serbia within three weeks of the signing of the convention, while Bulgaria had to do the same within 25 days of that date. Germany and Austria-Hungary were to field at least six infantry divisions for the attack, and Bulgaria at least four infantry divisions according to their established tables and organization. All these forces were to be placed under the command of

Generalfeldmarschall August von Mackensen, whose task wad defined as "to fight the Serbian Army wherever he finds it and to open and insure as soon as possible a land connection between

Hungary and

Bulgaria". Germany also pledged to assist with what ever war material Bulgaria needed unless it harmed Germany's own needs. Bulgaria was to mobilize the 4 divisions within 15 days of the signing of the convention and furnish at least one more division (outside of Mackensen's command and forces) that was to occupy

Vardar Macedonia. Bulgaria also pledged to keep strict neutrality against Greece and Romania for the duration of the war operations against Serbia, as long as the two countries remained neutral themselves. The

Ottoman Empire was given the right to adhere to all points of the military convention and

von Falkenhayn was to open immediate negotiations with its representatives. On its part Bulgaria agreed to give full passage to all materials and soldiers sent from Germany and Austria-Hungary to the

Ottoman Empire, as soon as a connection through Serbia, the Danube or Romania had been opened.

On the same day, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire concluded a separate agreement that granted Bulgaria the possession of the remaining Ottoman lands west of the river

Maritsa including a 2-kilometer stretch on its eastern bank that ran along the entire length of the river. This placed the railway to the Aegean port of

Dedeagach and some 2,587 square kilometers (999 square miles) under Bulgarian control.

The Allies were unaware of the treaty between Bulgaria and Germany and on August 6, made a new attempt to gain Bulgarian support by offering the occupation of the uncontested zone by Allied troops as a guarantee that Bulgaria would receive it after it had attacked the Ottoman Empire following the landings at Suvla. This offer was a sign of desperation, however, and even the British foreign minister criticized it as inadequate. Radoslavov decided to play along and asked for further clarification. When the landings commenced, the Bulgarians decided to wait for news at that sector, but when it was confirmed the Anzac troops were stalled, Bulgaria refused the offer on 10 August.

Back on July 22, Bulgaria declared general mobilization and Radoslavov stated that country would assume a state of "armed neutrality" which its neighbors should not perceive as a threat. This event was indicative of Bulgarian intentions and prompted the Serbians to ask the

Entente to support them in a preemptive strike on Bulgaria, which was now impossible due to the Austro-Hungarian invasion of their homeland. The Allies were not yet ready to help Serbia in a military way and refused, focusing their efforts instead on finding ways to delay as much as possible the seemingly imminent Bulgarian attack. Sazonov, angered by this "Bulgarian betrayal", insisted that a clear ultimatum should be issued to the Balkan country. The French and the British resisted at first but eventually fell in line with the Russians and on 12 August, the Entente presented an ultimatum demanding all German officers attached to the Bulgarian army be sent back to home within 24 hours. Radoslavov did not reply and on 13 August, the Allied representatives asked for their passports and left Sofia.

On the following day, Bulgaria officially declared war on Serbia and the Bulgarian Army invaded Serbian territory. British

Prime Minister H. H. Asquith concluded that "one of the most important chapters in the history of diplomacy" had ended. He blamed this heavy Allied diplomatic defeat on Russia and most of all on Serbia and its "obstinacy and cupidity". In military terms, Bulgaria's involvement also made the position of the Allies in Gallipoli untenable.