Prologue

“We sat grown quiet at the name of love;

We saw the last embers of daylight die,

And in the trembling blue-green of the sky

A moon, worn as if it had been a shell

Washed by time's waters as they rose and fell

About the stars and broke in days and years.

I had a thought for no one's but your ears:

That you were beautiful, and that I strove

To love you in the old high way of love;

That it had all seemed happy, and yet we'd grown

As weary-hearted as that hollow moon.”

--W.B. Yeats, In the Seven Woods: Being Poems Chiefly of the Irish Heroic Age

“History, Stephen said, is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake.”

--James Joyce, Ulysses

Leinster House Today

For decades, it has been impossible for responsible historians within and without Ireland to write a true and proper account of Irish modern history, John Turnley’s excellent effort A People’s History of the Free State of Ireland notwithstanding(1). In the past, this was largely due to the immense isolation of the National Guard regime and its masterful warping of any and all information leaving its island fortress. However, even after the fall of the fascist regime and the first tentative steps towards democracy, 20th-century Irish history has suffered within it a great hole; to many, it is as though history ended when the National Guard seized control of Leinster House in 1933 and only began again with the Irish Spring in 1994.

One of the many mass graves found near Cork

It is fascinating that the famously introspective Irish people have chosen to neglect this most recent part of their history. With the final declassification of National Guard documents in 2008, however, this reticence has become more understandable. The horrific actions of the nationalist regime--mass murder, brutal suppression, the imprisonment of hundreds of thousands, and the forced restructuring of Irish society which killed further hundreds of thousands--have clawed deep scars into the Irish psyche. As with the post-Soviet republics and the post-fascist Iberian states, it is essential to the reconstruction of national spirit that the Irish face and understand their heritage, brutal as it might be.

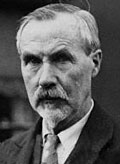

Eoin O'Duffy as a young man

Try as we may, it is impossible to discuss any modern history of Ireland without an examination of Eoin O’Duffy, its most controversial leader. O’Duffy, the infamous founder of the National Guard, had been born in 1892 in County Monaghan, at Lough Egish. Though he had been born into a happy family, his life took a turn for the tragic in 1904, when his mother died. The young O’Duffy was deeply scarred by his mother’s death, and wore her wedding ring until his own death in 1954. O’Duffy worked as an engineer until 1917, when he joined the Irish Volunteers during the Anglo-Irish War. The young man distinguished himself greatly during the war, wherein he showed a talent for command, shown most notably in the Battle of Ballytrain. Here, O’Duffy, Peader O’Donnell (later the face of domestic opposition to the National Guard), and Ernie O’Malley (who would later fight against the fledgling Irish state in the First Civil War and become a major critic of O’Duffy’s regime in the United States), led a force of thirty men to destroy the local barracks and arms depot; it was one of the first major IRA incursions against British arms. This incident is notable for the three very different personalities it combined, all of whom would later battle in the divisive sectarian conflict of the next twenty years.

Pro-Treaty IRA under fire from Anti-Treaty forces

O’Duffy became director of the army in 1921 and was elected to the Dáil Éireann in the same year. During the First Civil War, O’Duffy was first stationed in Belfast, where he successfully protected Northern Irish Catholics from attack by Unionists, and fostered good military relations with the British, which would be crucial in his later handling of the Anglo-Irish Trade War. As the war entered 1922, O’Duffy was promoted to general (becoming the youngest until Francisco Franco) and became the IRA’s chief of staff, later successfully capturing Limerick and spearheading the tactic of seaborne landings onto Anti-Treaty areas. What is interesting to note is that despite his siding with the Treaty IRA, O’Duffy was a significant critic of the Treaty Ports (southern Irish ports that would continue to be used by the Royal Navy after independence, according to the treaty) and the retention of Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom. These concerns would (much) later be sidelined in favor of political pragmatism as O’Duffy’s regime faced the very real concern of British invasion if he refused to toe the line.

Eamon de Valera, last President of the Executive Council of Ireland

At the end of the civil war, O’Duffy left the military and became police commissioner on the recommendation of Kevin O’Higgins. His truly outstanding organizational skills soon put paid to the widespread insubordination that had dominated the Garda before his appointment, and the sternly Catholic, nationalist ethos which he instilled in the police would have far-reaching ramifications in the coming conflicts of the 1930s. Ten years later, after the fall of the Cumann na nGaedheal government in early 1933 and the rise of Eamon de Valera, O’Duffy was dismissed as commissioner; on the surface, this was because of his deep political ties to Cumann na nGaedheal. However, records of conversations and private diaries recovered after the fall of the National Guard have revealed that O’Duffy’s dismissal was actually due to his strong advocation of a military coup to avoid the incoming Fianna Fail government. Some less reputable historians have had a field day with this idea, delving into counterfactual history to paint a portrait of a world in which O’Duffy fails and is executed, thus avoiding Ireland’s descent into civil war and authoritarianism. I feel obligated to remind these men, however, that Cumann na nGaedheal was at the time just as opposed to the idea of a coup as Fianna Fail was; O’Duffy never could or would have acted thusly without more support.

A Blueshirt rally in Cork

This support he found in the Army Comrades Association or ACA, a group of veterans and young, fervent nationalists set up to protect CnG meetings from the pro-FF partisans which had begun mistreating CnG members since the end of the First Civil War. Although it had, under its founding leader Thomas F. O’Higgins, been simply an organization to provide protection for pro-Treaty veterans and voters, O’Duffy changed the group into something altogether stronger and more malicious. Only a month after he became the ACA’s leader, he formally changed the name of the group to the National Guard or Garda Náisiúnta (GN). New, bright blue uniforms were adopted, leading to the infamous nickname “Blueshirt” to designate a GN partisan. The Roman salute was also adopted, as was military discipline. Alongside other such cosmetic changes was the new constitution O’Duffy enacted for the GN, which fundamentally changed the purpose and makeup of the group. According to this constitution, the group’s main political aims were:

--To promote the reunification of Ireland.

--To oppose Communism and alien control and influence in national affairs and to uphold Christian principles in every sphere of public activity.

--To promote and maintain social order.

--To make organised and disciplined voluntary public service a permanent and accepted feature of Irish political life and to lead the youth of Ireland in a movement of constructive national action.

--To promote of co-ordinated national organisations of employers and employed, which with the aid of judicial tribunals, will effectively prevent strikes and lock-outs and harmoniously compose industrial influences.

--To cooperate with the official agencies of the state for the solution of such pressing social problems as the provision of useful and economic public employment for those whom private enterprise cannot absorb.

--To secure the creation of a representative national statutory organisation of farmers, with rights and status sufficient to secure the safeguarding of agricultural interests, in all revisions of agricultural and political policy.

--To expose and prevent corruption and victimisation in national and local administration.

--To awaken throughout the country a spirit of combination, discipline, zeal and patriotic realism which will put the state in a position to serve the people efficiently in the economic and social spheres.(2)

A National Guard uniform

The sixth provision of this new constitution would steadily be ignored by O’Duffy and his radical group as they rose to power. By July 1933, the organization was composed of some 40,000 men, trained and armed by O’Duffy as a powerful paramilitary force, and instilled with his corporatist ethos. The new government watched these developments with some trepidation--the memories of Mussolini’s March on Rome and, more recently, the beginnings of Hitler’s rise to power, were all too fresh a warning for democratic governments. It was in August that these tensions finally came to a head. The National Guard announced that they would be holding a march in Dublin to honor Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith, prominent Irish nationalists that had died eleven years before. Fearing an Irish version of Mussolini’s seizure of power, de Valera’s government immediately banned the march and the National Guard. This struck O’Duffy deeply--though he was a fervent corporatist and deeply against de Valera, he had worked loyally with the government of Ireland for years. He vacillated between outright breaking with the government and following the law for several days. Finally, on August 10, the decision was made.

The Taking of Leinster House, Irish Realist drawing from the 1970s.

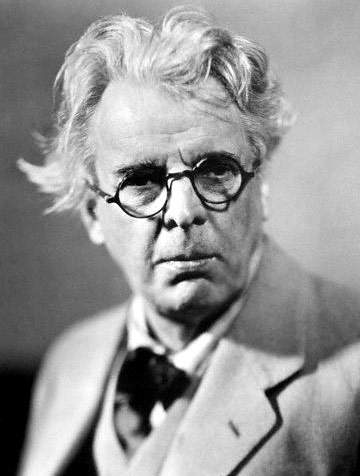

On August 13, 1933, 25,000 members of the National Guard marched on Dublin, where a large group of the Irish military awaited them, supplemented by police. Behind them further, Anti-Treaty IRA and pro-Fianna Fail protested loudly against the Blueshirts. Coming directly face to face with the military forces, the Blueshirts, led by O’Duffy himself, were silent for several moments. It is one of the most dramatic moments of the 20th century; military and paramilitary silently standing each other down while anti-Blueshirt protesters egged them on. Then, something broke as O’Duffy stepped forward and saluted the soldiers. Many of them had served under the former general; the police, too, remembered his era fondly. Some breaking into tears, the group, en masse, saluted O’Duffy and joined his march(3), swiftly pushing aside the protesters, violently in many cases. The march made a short stop at Glasnevin Cemetery, where emotional speeches were held in which many again lost themselves to tears. After the march, numbering almost 40,000 now, left the cemetery, many had been stirred up into a rage by O’Duffy’s inflammatory speeches and the left-wing opposition encountered. Trumpeting O’Duffy as “true leader of Ireland”, the marchers encamped themselves outside Leinster House, where they demanded that O’Duffy immediately be installed as Taoiseach, and a National Guard transitional government be put in. At around 3:00, the tense standoff between the marchers and the few loyal policemen was broken as one of the marchers, perhaps itching for a battle, flung a rock at Leinster House, causing the policemen to begin firing on the crowd. Howling for blood, O’Duffy’s men overwhelmed police barricades and charged into Leinster House, where (very luckily) Eamon de Valera and his cabinet had already fled, to Cork. The TDs remaining who did not surrender immediately or openly join the rioters were beaten, in many cases to death. One of the unfortunate casualties of this attack was none other than the aging W.B. Yeats, who did in fact support the movement.

W.B. Yeats, a tragic casualty of the fascists' rise to power

Only an hour later, Eoin O’Duffy, surrounded by loyal Blueshirts, proclaimed the State of Ireland from the balcony of Leinster House with himself as the first Stiúrthóir ("Director" in Irish), to be cheered on by his supporters. In those heady moments, it was surely easy to forget that the government of de Valera survived and that there remained significant opposition to the National Guard.

The Second Irish Civil War had begun.

Notes

(1) John Turnley was, IOTL, a pro-unification Northern Irish activist. Here, he's much more radicalized.

(2) To avoid accusations of plagiarism, I would like to state full-out that the constitution written here is taken almost word for word (besides a few cosmetic changes) from the actual text of the constitution, in the interest of historical accuracy.

(3) This is exactly what de Valera feared would happen IOTL, and it's not too out there for it to actually happen here.

* * *

Yep, a fascist Ireland. It's happening. This isn't going to be a TLIAW like I had planned; it's going to be rather a bit more expansive than that. Anyway, enjoy, and please comment! It cheers me up.

Last edited: