I'm so very sorry for any inconvieniences that the ending of the first two TLs may have caused you. But now, there is a new POD, but the same general idea, and maps and flags will be posted every 5th Chapter. Enjoy!

During the Democratic campaign of 1844, James K. Polk pushed for annexation of both Texas and, more importantly, the Oregon territory, which was disputed between Britain and the U.S. at the time. This appealed to both Northern and Southern expansionists, and would lead to the election of Polk as President of the United States, mainly because the opposition, Henry Clay, pushed against expansion. As he was inaugurated in March, 1845, he stated that the U.S. had a “clear and indefinite claim” to Oregon, and that neither Britain nor any other power, could take that away from them. Polk believed that strong posturing and a show of power would intimidate Britain into giving in to an acceptable resolution that would please the United States, and proceeded to do so as the two countries fortified the northern borders in preparation for war. He also rejected all offers by the U.K. that would use arbitration, and continued to push for the whole region. The public called out for the entire region, as mentioned in the 1844 Democratic campaign. On December 27th, 1845, the term “Manifest Destiny” was coined by John L. O’Sullivan describing American entitlement to the whole of Oregon, and would be used by expansionists for years to come.

Meanwhile, calls of war were erupting from the public over British mistrust and the belief that the U.S. would use the land more efficiently than the British. This, coupled with the bitterness that Northerners felt when Polk would compromise over Oregon but not Texas, and that many Senators of Michigan, Indiana and Ohio (note that these states were close to the northern borders, especially Michigan) were willing to push for war rather than accept anything less of “54’40” created enough political pressure to cause Polk to finally sever negotiations permanently with Great Britain. The British, not wanting of another war, finally gave into the demands of the U.S., but only if they came up with a good enough deal. On June 15th, 1846, the U.S. offered that a joint occupation between Britain and the U.S., that would allow both American and British colonists to occupy the whole territory, and that both nations would govern their own people from the split capital of Vancouver. East Vancouver would be controlled by the British and West Vancouver would be controlled by the Americans. The offer also mentioned the Hudson Bay Company and its monopoly among the fur trade on the Western Pacific Coast, and how they may continue their trade, but must relinquish all monopolies on the fur trade and allow free trade that is beyond their control. The British accepted these terms, and although they were bitter about the Hudson Bay Company section of the treaty, were still happy that it had not come to war between the two nations as they had more important things to worry about such as the Irish potato famine, and the U.S. pleased that they had both gained the Oregon territory and Texas that year. Many expansionists rejoiced, and even though they didn’t trust the British, they were glad that America had followed the Manifest Destiny. The newly gained Oregon territory would also help build a better American presence in the Pacific, and start the foundations of Fort Dwayne, a naval base that would help encourage trade between the U.S. and many of the colonial and Asian powers.

The years following the Oregon Treaty of 1846, many American pioneers moved towards the newly attained Oregon territory, even though the U.S. still didn’t trust the British, they were still willing to share the territory as long as they still had control through numbers. In fact, they did, as very few British colonists came to Oregon during the intermission, while the Americans had already established a naval base and a base population of at least 145 people. After the relatively peaceful nine years, the Fraser Gold Rush caused American colonists to again question the Oregon Treaty of 1846, more specifically the shared rule between Britain and America. During the Fraser Gold Rush, over 30,000 American miners and pioneers came from all around the Continental U.S., a lot more than the measly 400 that the British had. Anyways, during this short period of economic prosperity, the British-controlled East Vancouver complained that the large American population was taking homes and jobs meant for the British, and the American-controlled West Vancouver countered by stating that very few British had even come to Oregon, while the Americans had a naval base and a rapidly growing population. When the British began evicting Americans from their homes, and stopped American miners from claiming land, Americans responded by rioting and vandalizing much British-owned property on the night of August 19th, 1856 known as “Dark Tuesday”. West Vancouver had to pay $1,000 for the damages caused by the American citizens, and both Secretary of State William L. Marcy and Secretary of Foreign Affairs knew it was time for another negotiation to take place. On the 30th of August, President Franklin Pierce and Prime Minister Henry John Temple began negotiations that would rearrange the Oregon Treaty. On November 5th, 1856, a deal would allow certain British laws to apply to both types of citizens. Although that made it seem that the British were in control, appealing to the Prime Minister, it actually gave the U.S. more power in the Oregon Territorial Government, weakening Britain’s control, bound to affect the history of the future. Even though American citizens were angered that they had to follow British rules, they were no longer discriminated by the British, and continued the gold rush until 1860. After the Fraser Gold Rush, many Americans continued to stay in Oregon territory, mining the coal reservoirs, and although some Americans left for more gold rushes, the Americans remained even after the British residents were nearly non-existent. This would continue to persist even after the American Civil War.

“The citizens of the U.S. deserve all rights that their British counterparts, and I call upon the Prime Minister of Great Britain to stop this buffoonery, and make peace!” – Secretary of State William L. Marcy, at the Conference of 1856, talking about the reconstruction of the Oregon Treaty of 1856.

Chapter One

“Fraser Gold Rush and 54'40”

A TL

“Fraser Gold Rush and 54'40”

A TL

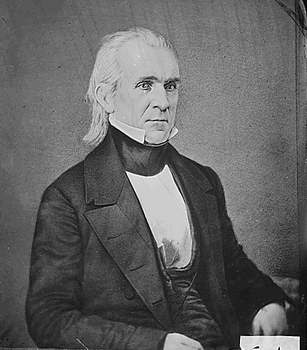

A representation of the “indefinite” claim the U.S. made in 1844, during the Democratic campaign. This got much popular support by the public, leading to the election of Polk.

“The whole land of Oregon is an indefinite and unquestionable claim to the U.S., and will not be ceded nor sold to any other power…I, and many others like me, are willing to go to war with Great Britain for our land.” – A quote from the speech of James K. Polk during the 1844 Democratic National Convention.

During the Democratic campaign of 1844, James K. Polk pushed for annexation of both Texas and, more importantly, the Oregon territory, which was disputed between Britain and the U.S. at the time. This appealed to both Northern and Southern expansionists, and would lead to the election of Polk as President of the United States, mainly because the opposition, Henry Clay, pushed against expansion. As he was inaugurated in March, 1845, he stated that the U.S. had a “clear and indefinite claim” to Oregon, and that neither Britain nor any other power, could take that away from them. Polk believed that strong posturing and a show of power would intimidate Britain into giving in to an acceptable resolution that would please the United States, and proceeded to do so as the two countries fortified the northern borders in preparation for war. He also rejected all offers by the U.K. that would use arbitration, and continued to push for the whole region. The public called out for the entire region, as mentioned in the 1844 Democratic campaign. On December 27th, 1845, the term “Manifest Destiny” was coined by John L. O’Sullivan describing American entitlement to the whole of Oregon, and would be used by expansionists for years to come.

Meanwhile, calls of war were erupting from the public over British mistrust and the belief that the U.S. would use the land more efficiently than the British. This, coupled with the bitterness that Northerners felt when Polk would compromise over Oregon but not Texas, and that many Senators of Michigan, Indiana and Ohio (note that these states were close to the northern borders, especially Michigan) were willing to push for war rather than accept anything less of “54’40” created enough political pressure to cause Polk to finally sever negotiations permanently with Great Britain. The British, not wanting of another war, finally gave into the demands of the U.S., but only if they came up with a good enough deal. On June 15th, 1846, the U.S. offered that a joint occupation between Britain and the U.S., that would allow both American and British colonists to occupy the whole territory, and that both nations would govern their own people from the split capital of Vancouver. East Vancouver would be controlled by the British and West Vancouver would be controlled by the Americans. The offer also mentioned the Hudson Bay Company and its monopoly among the fur trade on the Western Pacific Coast, and how they may continue their trade, but must relinquish all monopolies on the fur trade and allow free trade that is beyond their control. The British accepted these terms, and although they were bitter about the Hudson Bay Company section of the treaty, were still happy that it had not come to war between the two nations as they had more important things to worry about such as the Irish potato famine, and the U.S. pleased that they had both gained the Oregon territory and Texas that year. Many expansionists rejoiced, and even though they didn’t trust the British, they were glad that America had followed the Manifest Destiny. The newly gained Oregon territory would also help build a better American presence in the Pacific, and start the foundations of Fort Dwayne, a naval base that would help encourage trade between the U.S. and many of the colonial and Asian powers.

The years following the Oregon Treaty of 1846, many American pioneers moved towards the newly attained Oregon territory, even though the U.S. still didn’t trust the British, they were still willing to share the territory as long as they still had control through numbers. In fact, they did, as very few British colonists came to Oregon during the intermission, while the Americans had already established a naval base and a base population of at least 145 people. After the relatively peaceful nine years, the Fraser Gold Rush caused American colonists to again question the Oregon Treaty of 1846, more specifically the shared rule between Britain and America. During the Fraser Gold Rush, over 30,000 American miners and pioneers came from all around the Continental U.S., a lot more than the measly 400 that the British had. Anyways, during this short period of economic prosperity, the British-controlled East Vancouver complained that the large American population was taking homes and jobs meant for the British, and the American-controlled West Vancouver countered by stating that very few British had even come to Oregon, while the Americans had a naval base and a rapidly growing population. When the British began evicting Americans from their homes, and stopped American miners from claiming land, Americans responded by rioting and vandalizing much British-owned property on the night of August 19th, 1856 known as “Dark Tuesday”. West Vancouver had to pay $1,000 for the damages caused by the American citizens, and both Secretary of State William L. Marcy and Secretary of Foreign Affairs knew it was time for another negotiation to take place. On the 30th of August, President Franklin Pierce and Prime Minister Henry John Temple began negotiations that would rearrange the Oregon Treaty. On November 5th, 1856, a deal would allow certain British laws to apply to both types of citizens. Although that made it seem that the British were in control, appealing to the Prime Minister, it actually gave the U.S. more power in the Oregon Territorial Government, weakening Britain’s control, bound to affect the history of the future. Even though American citizens were angered that they had to follow British rules, they were no longer discriminated by the British, and continued the gold rush until 1860. After the Fraser Gold Rush, many Americans continued to stay in Oregon territory, mining the coal reservoirs, and although some Americans left for more gold rushes, the Americans remained even after the British residents were nearly non-existent. This would continue to persist even after the American Civil War.

“The citizens of the U.S. deserve all rights that their British counterparts, and I call upon the Prime Minister of Great Britain to stop this buffoonery, and make peace!” – Secretary of State William L. Marcy, at the Conference of 1856, talking about the reconstruction of the Oregon Treaty of 1856.

Last edited: