Hi to everyone! After almost a year of absence, I finally returned quite motivated to conclude this TL (https://www.alternatehistory.com/discussion/showthread.php?t=177322) I started time ago. However, instead to continue where I left I decided instead to start a V.2 revised and corrected, and even enriched with more notions and the insertion of images and maps (about those I'll try my best, but don't expect wonders from me...

This project is supposed to develop through three acts, the first one which will be a retake of what I wrote the first time: however, I already want to announce that respect to the V.1 some of the events which didn't convince me completely will be revised if not changed. However, suggestions and comments are always welcomed as usual, and I hope not only to regain the old public but also conquer new readers as well. Finally, I'll try to update with regularity and to not remain too inactive like the last months of my previous try. So bombard me with request of updates!

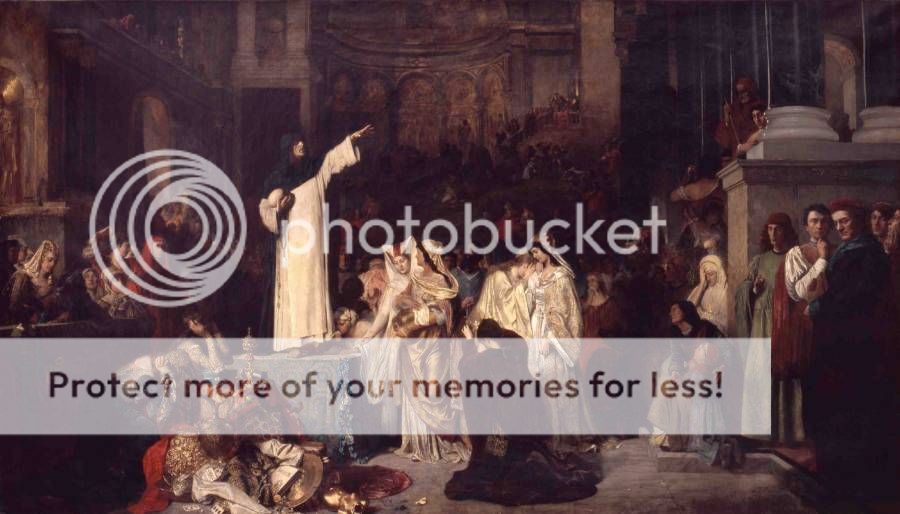

Fine enough, it's time to start with the first chapter of the first act, every one marked with its proper marker. Here's the actual one for the moment (maybe later I will replace it with another better, who knows?

Chapter one

“Per il bene di Fiorenza, che la Repubblica moia e viva il Principato! ( For the good of Florence, the Republic must die and the Principate live!)” – Angelo PolizianoFrom “History of modern Italy, volume one: the rise of the Principate of Tuscany”

Drawing of Florence said "della catena", by Francesco di Lorenzo Rosselli, around 1471-1482. It shows the Toscan city during the rule of Lorenzo de'Medici, in the years immediately next to the Pazzi conspiracy.

Despite the failure of the Pazzi conspiracy, in 1478 the situation looked very grim for the Florentine Republic and his de facto sovereign, Lorenzo de Medici. The main promoter of the failed coup, Pope Sixtus IV, decided to pursue at all costs the intention to claim the rich lands of Florence for his family by excommunicating Lorenzo and the high offices of the Republic for the assassination of the plotters, and launching a full-scale diplomatic offensive in order to isolate the Tuscan city.

The Pope managed to convince the city of Siena, main rival of Florence for the control of Tuscany, and Ferdinand I of Naples, interested to expand his influence in Central Italy in prevision of a future intervention in the North, to join arms with the Papacy against the excommunicated Republic; on the other side, Florence soon discovered to be alone, as her main allies were unable to intervene. In fact, Milan was engulfed in a civil war after the assassination of Galeazzo Maria Sforza, Venice was fighting the Turks and the French were involved in Burgundian affairs. Other near states as Lucca and Urbino (where in recent times it was discovered a letter which confirmed the support to the attemped coup by Federico da Montefeltro, even if Lorenzo never suspected his involvement) remained neutral despite it was clear they hoped for the Florentine defeat as well.

The front situation at the start of the "Tuscan-Papal war" in early 1478. Florence (blue) was alone against the coalition (red) composed by the Papacy, Siena, and Aragonese Naples. Despite the apparent disparity of forces, the coalition was more weak than expected: the city of Siena wasn't too far from the Florentine frontier, the lords and the cities of Marche and Romagna remained neutral giving Florence the security in the northern and the eastern borders, while Ferdinand soon saw the risks of a war where the Papacy will become more stronger in case of victory...

In a desperate situation like that, to Lorenzo came in help the wind of the new cultural ideas whose in these years from Italy are spreading all across Europe. The Medici lord was a man of great culture, and realized the philosophical concepts of the Renaissance Humanism could be used to renovate and revitalize the assets of the Republic not only for the imminent danger, but also for the years to come. However, Lorenzo realized soon that in order to take his reform plan, it was necessary to him to govern the country in first person, and not behind the shadows like his father and grandfather before him (and as he did until the conspiracy), even at cost to lose everything in case of failure; but he decided nevertheless to accept the challenge.Already in the early May of 1478, Lorenzo presented at Palazzo Vecchio in front of the Republican organs the results of his reflections, developed with the help of his inner circle of intellectuals leaded by Angelo Poliziano, famous writer of the period; to the meeting were present also delegates from the major cities controlled by the Republic, as Pisa, Arezzo, Pistoia and Prato, and previously called by the same Lorenzo. To the surprise of many Florentines, Lorenzo claimed that the Republic, which controlled the majority of the Tuscan territory, couldn’t claim any more to be only “Florentine” but it had the right to bring the name “Tuscany” instead; as consequence, the Republic couldn’t have the presumption to be ruled only by Florence but it needed to share the power with the other cities under its control. The final result, in Lorenzo’s opinion, was to reform as soon as possible the medieval city assembly into a real legislative chamber where all the cities and the various counties of the Republic were present.

Palazzo Vecchio, or Palazzo del Principato in Florence, seat of the medieval council of the Tuscan city. In 1478 it hosted the works of the delegates arrived from all Florentine Tuscany, which results made the complex the seat of the first "parliament" of the modern age in Italy - and Europe as well. Today, it is the seat of the communal administration of the city, as in the past.

It was soon clear the proposal encountered the immediate approval from the delegates of the other cities, and opposition in some parts of the Florentine noble and merchantile families, not willing to share part of their power with the rest of the Tuscans, but Lorenzo managed to convince them with personal donations and the reassurance the majority of the assembly will be composed by Florentines; also, he made them clearly understand the Florentines without the support of the other controlled cities they will be not a match against all of Central and Southern Italy.To further legitimate the process of reform of the Republic in the eyes of the local population and in the international opinion, Lorenzo also proposed to recall in some way the ancient Roman traditions, by giving not only to the new assembly the name of “Senate” (the complete term was “Nobile Senato di Toscana” or “Noble Senate of Tuscany”), but also to make the head of state of the country the leader of the same Senate, the one that in Roman tradition was called the “Princeps”, “Principe” in Italian (“Prince” in English), which after Augustus became the legitimate charge for the Roman Emperors to rule; however Lorenzo immediately declared that the term Prince was to be intended in his original use during the Republican age, and assured that Tuscany will be and will remain a Republic.

Lastly, Lorenzo gained the support of the local clergy promising it will have a small but solid presence in the Senate, plus the confirmation of his traditional privileges, in exchange of full support for the reforms and a common stand against the Pope in the imminent war; in reason of that, the Archbishop of Florence Rinaldo Orsini, tied with the Medici because of the wedding of his parent Clarice with Lorenzo, soon declared the invalidity of the excommunication because first the plotters killed Giuliano de’Medici in the Dome of Florence, and second Lorenzo and the Florentine authorities didn’t give order to the people to assault them, and in any way the conjurors with that act became traitors and deserved that punition. Other bishops of the Republic supported that position, more in spite of Sixtus IV that hoping for a victory which at the time seemed impossible, receiving in exchange from Rome the excommunication; in reply, they declared the Pope decayed because of his corrupt and nepotistic policy. Anyway, the Tuscan clergy remained compact behind Lorenzo until the end of the war.

Gained the necessary support, and after a further discussion about the modification of the Republican offices and administration, the 24th May 1476 the old Florentine Council was dissolved and replaced by a Senate composed by 300 members, with about the 62% composed by Florentines but nevertheless still with a strong presence from the other cities and counties, Pisa, Pistoia and Arezzo in particular. It was decided that the term of a senator will be for life but not hereditary, and future replacements will be chosen from candidates promoted by the Prince, in charge of the internal and external affairs of the Republic. Naturally, Lorenzo de’Medici was elected first Prince of the new “Principate of Tuscany”, so starting a new course for the entire Italian peninsula…

Lorenzo de'Medici, first Prince of Tuscany. The danger of the imminent war with the Papacy and the new constitutional asset of the Republic forced him to directly assume the rule of Florence and his domains. Still de jure a Republic, Florence - now Tuscany - de facto became another Italian Signoria...