Part I, Chapter VI: The American Expeditions

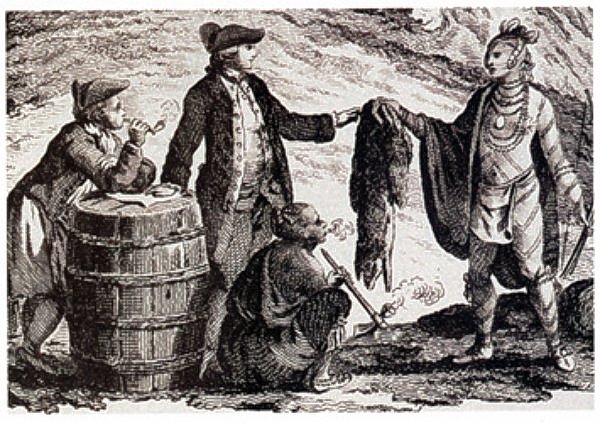

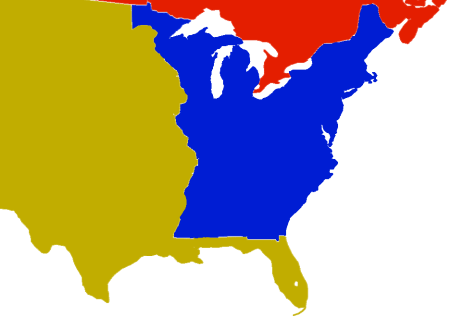

The Treaty of Paris in 1763 at the end of the French and Indian War had changed the ruling power of the Louisiana Territory and the Upper Midwest overnight. The entity known as New France that once spanned from the bayous of Louisiana all the way to the colony of Acadia had been shattered and retained only a token amount of governance in the New World in comparison to its former expansive territory. The clauses of the Treaty had regulated France to their only remaining North American possessions, the Caribbean Island colonies of Guadeloupe, Martinique, and Saint Lucia. Nonetheless, their largest colonies in the Upper Midwest - Michigan, Minnesota and Wisconsin - had grown extensively over the 18th century as a result of the lucrative fur trade and the settlements established in these colonies had sweeping French speaking majorities. The deportation of Acadians from the northeastern colonies of North America during the war had emphasized Great Britain's unwillingness to negotiate with non-Anglo resistance to the expansion of its colonial goals, and now that these territories rested firmly in the grasp of British rule, their future was all but certain.

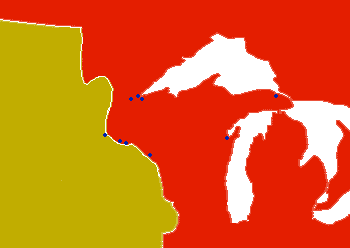

Major European trading posts and settlements in Minnesota, Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan by 1763. Fort du Lhut, Fort Le Sueur, Fort Pilante in British controlled Minnesota, and Fort Beauharnois in Spanish controlled Minnesota. In Wisconsin, the Green Bay Colony, the Prarie du Chien Colony, Fort Saint Antoine and Fort Perrot on Lake Pepin, and the La Pointe Colony. In Michigan, Sault Sainte Marie.

By 1765, however, it was clear the territories of the Upper Midwest would go relatively unharmed and unimpeded by the British, even despite a change in flags and ownership. The Treaty had provided a period of 18 months of amnesty for the remaining French speaking people in the newly acquired territories to relocate should they desire, and in some cases this relocation was subsidized and encouraged by the Crown in order to allow further Anglo colonization and to mitigate future problems that were likely to occur due to the disdain and animosity from their newly acquired subjects, who were certainly less than enthusiastic about being ruled by a now foreign crown. Furthermore, the remote location of the Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan colonies had dissuaded British interest, as they were also now forced to relocate assets to deal with an increasingly unruly Thirteen Colonies, who were beginning to voice their open discontent due to a sharp increase in taxes that had been imposed on the Colonies as a result of the massive amount of war expenditure Great Britain had accumulated in debt over the duration of hostilities with France.

Protest in the Thirteen Colonies regarding sharp increases in taxes as a result of war debt snuffed out British interest in the trivial Upper Midwest.

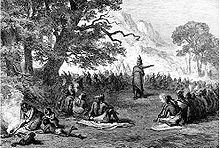

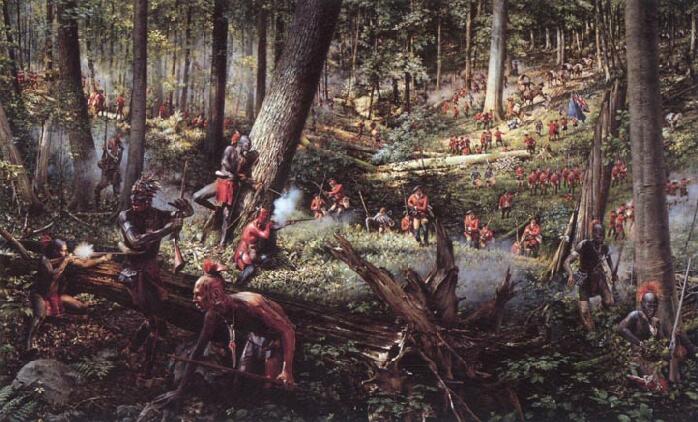

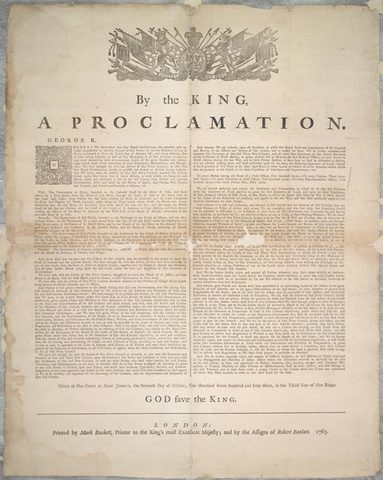

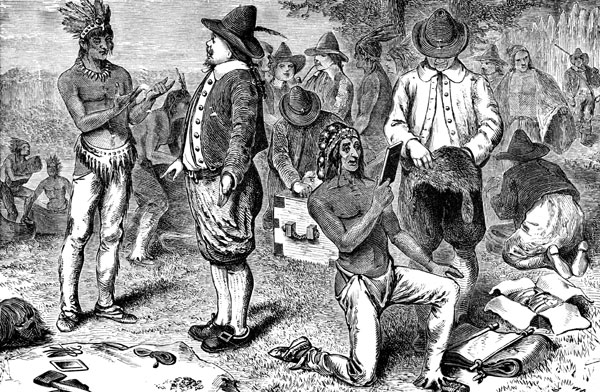

The end of the French and Indian War and the British acquisition of virtually all territory east of the Mississippi River had also opened this territory to Colonial expansion from the more well established and rapidly growing Thirteen Colonies, who viewed these new territories as a rightfully owed inheritance, and if anything a simple repayment for their struggle and sacrifice during the war. This radically early idea of Manifest Destiny, however, was quickly (and unintentionally) trampled by the British Crown when it issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which forbade American colonists from settling west of the Appalachian Mountains. Chief Pontiac and his Seneca Natives had become openly hostile by 1764, and had eliminated any chance of European travelers moving any further west than the Ohio River Valley, and the Iroquois Confederacy, although only a shadow of its former self, still remained as a significant threat along the Tennessee River. Regardless, the Proclamation would become a major grievance for the American colonists in the 1760's and well into the 1770's, and its stipulations would go widely ignored throughout the majority of the decade, as the British had very few means to enforce it. This would ultimately lead to a series of conflicts throughout the 1760's and 1770's (the most significant being Pontiac's War from 1763 - 1766) between the Natives and the American Colonists. Some of these conflicts would require intervention from British assets, and as a result lead to further taxation of the Colonies.

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 and Pontiac's War briefly eliminated any dreams European colonists once had of traveling further west than the Ohio River Valley.

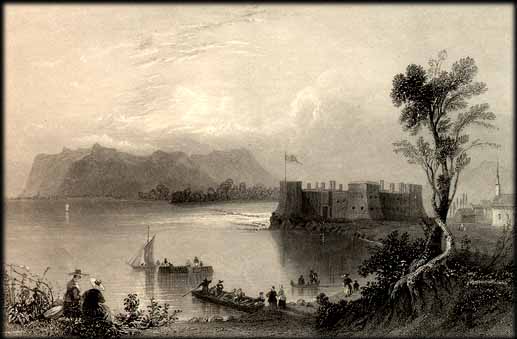

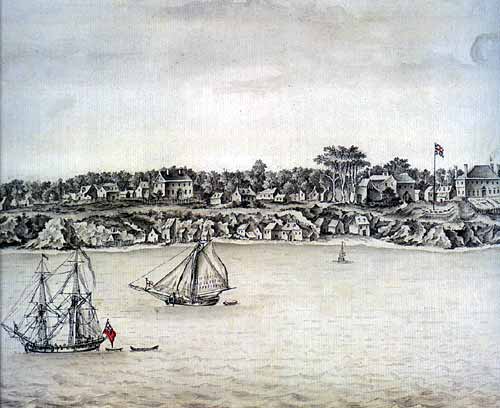

The issues further East with the hostile Seneca Natives and widespread American dissent throughout the Thirteen Colonies meant that the Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan colonies continued to see unimpeded fiscal growth throughout the 1760's and 1770's, even in British rule, mostly in part due to their strategic insignificance and remote location. The 18 month amnesty period that had been provided in the wake of the massive amount of territorial exchange in the Treaty of Paris in 1763 had granted French colonists subsidized relocation from the former colony of New France courtesy of the British Crown, but by 1764, this amnesty period had passed, and throughout many territories east and west of the Mississippi, the fur trade still proved to be profitable, and the majority of the French settlers that profited from the trade had simply refused the offer. The inability of the British to enforce a threat of deportation and a minimal amount of voluntary French relocation had lead to only a continuation of the status quo across the Upper Midwest. In fact, throughout the entire British "ownership" of the land, representations of the British government - other than its flag - never set foot in the Upper Midwest territories, with the one exception of a platoon of British rifles who briefly visited Green Bay in 1763. They stayed only for a short few days, and only in order to rearm and refit during the ongoing struggles with the Natives, and were later regarded only as a footnote and were treated well by the French settlers there, much to their surprise. Fort Beauharnois was also the only Upper Midwestern settlement considered to be in Spanish territory due to the Treaty of Fontainebleau, but because of its only trivial population, the now healthy relations between Spain and France, and the redirection of Spain's focus to its newly acquired Louisiana province, it was allowed to remain and saw no threat of closure or eventual deportation of its populace from the ruling Spanish governor of New Spain, Joaquin de Montserrat. It likewise would never see any presence of its new "owner."

Due to the Upper Midwest's inaccessibility, only Green Bay would see any real representation of its new territorial owners.

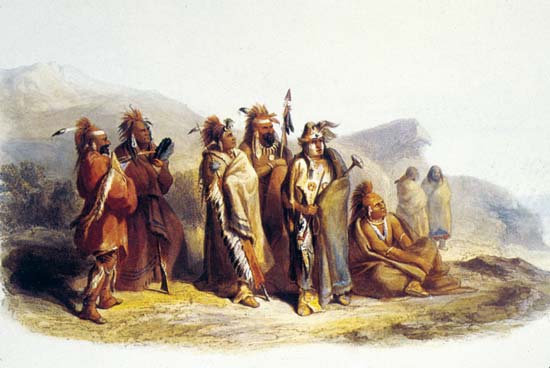

The destruction of Acadia and the capture of French Canada at the hands of combined Anglo efforts during the war had nonetheless disrupted the delicate position of the demographics of the Upper Midwest. Whereas the Thirteen Colonies numbered over 2,000,000 colonists of European origin by 1770, the permanent European settlers in Minnesota, Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan numbered only 1,000 - 920 of which were French. These numbers were doubled during the summer and fall months with the inclusion of up to 2,000 seasonal traders and missionaries as well, but their residencies were regarded as only temporary. In contrast, their Native American allies, the Sioux and Ojibwa, who still maintained a large presence (sometimes in extremely close proximity to settlements and trading posts) in the region numbered well over 50,000. Their numbers, however, were much less concentrated and unorganized than their European counterparts, and relations had fortunately remained friendly and stable, even despite the persecution of the Fox Natives following the Fox Wars. The reason for these low numbers was not only due to the remote location and inaccessibility of the regions, but also because during France's rule of the Louisiana Territory it was interested in little else but the fur trade, not settlement, and most colonization efforts were done strictly through private enterprise by the beginning of Queen Anne's War in the early 1700's. This demographic deficit was sharply emphasized by the loss of New France, as new settlers were few and far between, and the majority of New World French settlers had returned to France or settled in Louisiana following their displacement in the 1760's. The French and Indian War also saw close to 100 permanent French settlers and all of its permanent 20 British settlers to leave the Upper Midwest upon the declaration of hostilities, almost causing one of its settlements, Fort Beauharnois and its Catholic chapel in Minnesota, to be completely abandoned, and it was saved only by roughly two dozen displaced Acadians, who settled at the Fort in 1759.

The entire Upper Midwest totaled only 1,000 European settlers by 1770, as opposed to the Thirteen Colonies, who totaled nearly 2,000,000. The Natives in the Upper Midwest totaled roughly 50,000, but due to positive relations and trade with French settlers, they remained much less concentrated and organized than their Eastern cousins.

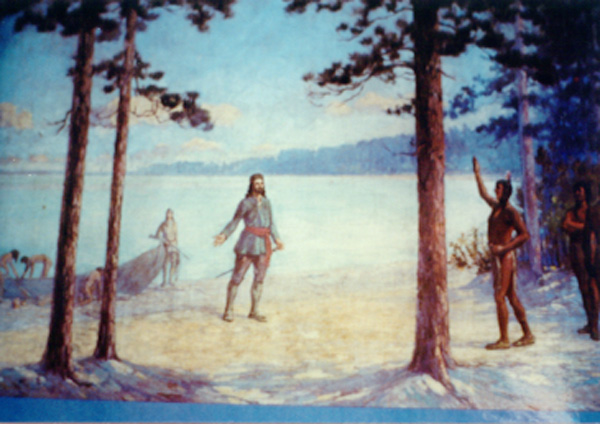

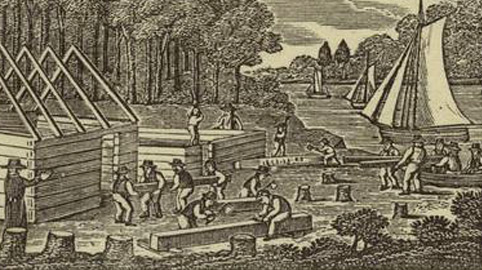

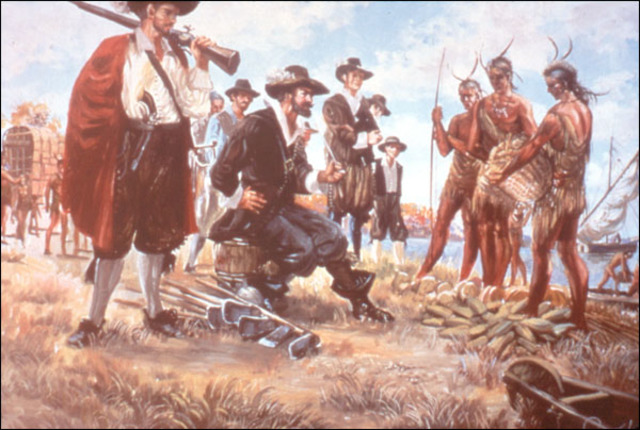

Nonetheless, due to its still lucrative fur trade, the inclusion of the Upper Midwest into territory now controlled by Great Britain and the conclusion of Native-Anglo warfare in the Great Lakes region following the end of Pontiac's War in 1766 improved interest in the area from British and American explorers and settlers, even after the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which was widely ignored. In 1770, Charles Michel de Langlade lead his expedition of 30 settlers from Massachusetts into the Wisconsin region in order to capitalize on the growing fur trade, and they settled a few miles west of the Green Bay area, making history as the first American settlement in Wisconsin. Jonathan Carver, a former American French and Indian War captain and his party of 12 other Americans from Connecticut and Massachusetts, also lead an expedition into the frontier when they were contracted by Robert Rogers, the famous French and Indian War commander and the leader of "Roger's Rangers," to find a western water route to the Pacific Ocean, which would later be known as the Northwest Passage. His efforts would be in vain as Carver was unable to find the passage as it was much farther north than he anticipated, but his party included two surveyors, and they mapped a good portion of the northwestern Wisconsin and southeastern Minnesota area before stopping briefly in Fort Beauharnois in 1768. Upon contacting Rogers, he no longer promised the appropriation of funds following Carver's perceived failure, and Carver instead lead his party north to Fort du Luht, where he would eventually settle with his family of seven children and his wife, Abigail Carver, after becoming a very successful trader due to his business experience in Connecticut. He and the 9 other members of his party that also chose to stay in the du Luht area would also make history, and became the first permanent American settlers in the Upper Midwest. The still lucrative fur trade in the regions continued to occur throughout the Upper Midwest well into the 1770's and as a result also saw a brief increase in European colonists after the end of Native tension along the Ohio River Valley, which would continue into the late 1770's.

Jonathan Carver, his family and 9 other members of his expeditionary party would eventually settle in du Luht following his failed expedition to find the Northwest Passage, becoming the first permanent American settlers in the Upper Midwest in 1768.

By 1775, however, the fate of the Upper Midwest was once again at the mercy of conflict in the east, and as a result once again out of the region's control. Unrelenting taxes, the garrison of British soldiers in American cities, and a lack of representation in British government had pushed the British Empire and its American colonies to the brink of war. As negotiations in London and Philadelphia broke down, the world held its breath once again, and it was clear the war for the independence of a nation was inevitable, but few, especially the small amount of colonists in the Upper Midwest, could imagine at what scale.

Taxes and treatment that was determined as unfair by American colonists in the Thirteen Colonies pushed both themselves and Great Britain to the brink of war, which would erupt into the American War of Independence in 1775.

Chapter I, Part VII: The American War of Independence