General Serrano's Regency, Part II: The Election of the new King

That was the political situation in Spain when, on 21st June 1870, an agent of the Spanish government in Berlin informed through telegraph about the acceptance of Prussian prince Leopold zu Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen for the candidacy that had been gestating from some time ago so that he could occupy the Spanish throne.

After the rotund failure

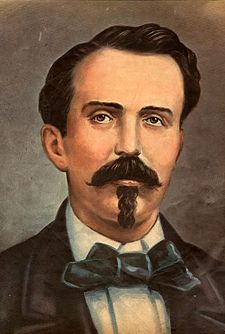

in extremis of the young Duke of Genoa's candidacy, there also was the flat refusal of General Espartero to become King of Spain, in spite of the popular support for his candidacy (due to his 77 years old, his lack of descendants and his wide experience in government responsibilities, many popular and political sectors saw him as the perfect candidate, especially the nostalgic Progressives, Ruiz Zorrilla's Radicals and even some Republicans) because he felt without the strength required to endure such responsibility.

Retired General Baldomero Fernández Espartero, former leader of the Progressive Party.

This situation was leading towards great tension in the political class that supported the constitutional monarchy (Prim himself stated

Finding a democratic king in Europe is harder than finding an atheist in Heaven!), strengthening the Republican position. Prim tried to win them and control the Spanish Republican movement by offering Emilio Castelar and Francisco Pi y Margall the positions of Ministers of Treasury and Public Works, respectively, but both of them refused, believing that soon the new monarchical regime would fail and there would be a chance to establish a Spanish Republic.

This was why Prim's government started to sound out certain princes in Central European nations that met the minimum requirements to be crowned King of Spain: that he was Catholic, that he accepted to swear allegiance to the 1869 Constitution and that he didn't meddle in the Spanish political life beyond his constitutional duties. Those requirements ruled out the candidates from the Habsburg dynasty (due to the traditionalism and Neocatholicism that Franz Joseph I represented) and the Wittelsbach dynasty from Bavaria (due to the congenital madness it suffered).

Austro-Hungarian Emperor Franz Joseph I.

Meanwhile, the Spanish representatives looked to the members of the reigning dynasty in Prussia, the Hohenzollern, as perfect, given that they had turned Prussia into Europe's emergent power and were doing a titanic job, mostly thanks to Chancellor Otto von Bismarck's negotiations, to turn into reality the dream of the German National Assembly established in Frankfurt during the 1848 Revolution: the unification of Germany in one sovereign state. However, there was a problem with that: the Hohenzollern were Protestants.

All these facts seemed to corroborate President Prim's sentence, but then the government was contacted by one of its emissaries in Berlin, Eusebio Salazar y Mazarredo, former secretary of the Spanish legislation in Berlin and later Deputy to Courts. From the first revolutionary plans to topple Isabella II, Salazar had already been projecting what he considered the perfect candidacy to the Spanish throne. In summer 1866 he met with Baron von Werthern, Prussian ambassador in Paris, in the city of Biarritz, a suitable summer resort for dignitaries and rich people of the time (amongst its most faithful visitors was Bismarck, which was probably one of the reasons for the choice of place, because the restless Spanish diplomat hoped to meet the Chancellor there) for a lunch meeting. The main conversation subject was the chance that the throne of Spain, for any reason, became vacant, and Baron von Werthern answered that, if that were to happen, the best candidate was Leopold zu Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen.

Prince Leopold zu Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen.

Leopold was the older son of Prince Karl Anton zu Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, head of the Hohenzollern branch that, in the 16th Century, planted their dominion in Swabia, and had given their rights in Swabia to their Prussian relatives after the 1848 Revolution. Also, Karl Anton had been Prussian Chancellor between 1858 and 1862 and was currently military governor of Rhineland and Westphalia, while Leopold was an officer in the Prussian Army and Karl Anton's second son, Karl, had been promoted in 1866 to the Romanian throne under the name of Carol I, so the possibility of Leopold accessing the Spanish throne didn't lack a precedent.

Besides, Leopold had several characteristics that made his candidacy even more attractive: for starters, Leopold was 35 years old; he was Catholic, as his whole family was (the Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen had remained faithful to Catholicism after the Protestant Reform); he was a very educated man, of great intelligence; his personal fortune was one of the most considerable in the continent; he was married to Portuguese Infanta Antónia de Saxe-Coburgo-Gota e Bragança (María II and Fernando de Saxe-Coburgo-Gota's daughter), which could give him the support of those that had looked for a candidate that could unify Spain and Portugal in one sovereign state, and he had his succession secured thanks to his sons Wilhelm (born in 1864) and Ferdinand (born in 1865), as well as, shortly before

the Glorious, his third son, Karl Anton.

Spanish diplomatic Eusebio Salazar y Mazarredo.

It was, thus, along 1869, that Salazar asked Prim to inform Bismarck of his intentions and for the government to officially support him through the Spanish ambassador in Berlin, Count Juan Antonio Rascón, to win the Chancellor's support for the Leopoldine candidacy.

Salazar's schemes were soon well-known in all Europe and came to the newspapers, creating a contrived situation from where the protagonists escaped faking ignorance of the matter while vital contacts of great importance were developed. Those contacts were transcribed into a secret visit of President Prim with his most trusted men to Leopold's father house, to propose him his son's candidacy to the Spanish throne. Both Leopold and Prussian King William I had doubts, given their distrust of the situation in Spain and the eternal pro-coup philosophy developed in the Spanish Army, but Otto von Bismarck was very interested in the chance of putting a Hohenzollern in the Spanish throne and became a support for the Spanish agents.

Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck.

At first sight, it seemed that the Prussian Chancellor was unflappable regarding Leopold's candidacy, but his closest confidants stated he was excited with it: his apparent indifference (in spite of Count Rascón's being a person of his liking and confidence) was due to the fact that he was planning to use the affair as a pretext to attract France into a war against Prussia that would end up in German unification, as well as slowly wear down his King's and Leopold's reticence.

With that objective in mind, Bismarck convinced William I to entrust Prince Karl Anton with a private dinner which was attended by Prince Leopold, Bismarck, General Helmuth von Moltke, the main Ministers, the Prussian King, and his son and heir, Kronprinz Friedrich. All those present were in favor of Leopold's acceptance of the Crown (with the aim of gaining France's southern neighbor as an faithful ally of Prussia), save for the King and Kronprinz, while Leopold remained ambiguous, awaiting the King's settlement. Bismarck then started a series of sibylline pressures to convince William I and the pretender of the great opportunities Leopold's accession to the Spanish throne would generate, both internally and externally, for Prussia.

Prince Karl Anton zu Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen.

It was then, in 21st June 1870, that Salazar notified through telegraph to the President of the Courts, Manuel Ruiz Zorrilla, Leopold's acceptance which he had been given while at the Bavarian spa of Reichenhall after William I approved it, and that he would arrive there near 6th July (*), in time to present it before the Courts, whose members were awaiting with impatience for the parliamentary session period to end, so that the candidacy was voted. The return of Salazar and his collaborators was not done unaccompanied, because, for their security and that of the candidacy, they were being accompanied by several secret agents of Bismarck's maximum confidence, who would join those that were already in Spain since before

the Glorious happened.

The Prussians were not the only ones that had sent spies to operate and watch out what was going on in Spain, and mainly in Madrid. France and its Emperor, Napoleon III, looked at Isabella II's overthrow with a mix of interest and distrust, so they had sent more agents than ever in order to know what was happening in Spain at first hand. In essence, this external policy towards Spain was very common in regards to the periodical interventions that France had carried out in Spain in the last decades (the most notorious examples were the Hundred Thousand Sons of Saint Louis, who invaded Spain in 1823 to reestablish Fernando VII's absolutism and end the constitutional experience originated in Lieutenant Colonel Rafael de Riego's 1820 uprising; and Isabella II's marriage in 1846, preventing the young queen from marrying Leopold, Fernando de Saxe-Coburgo-Gota's younger brother, as the British pretended, given that the dynasty (the Saxe-Coburg-Gotha) already ruled in Belgium, Portugal and Great Britain).

King William I of Prussia.

However, there was a great difference when compared with previous French interventions, veiled or clear, in Spanish politics. The growing mistakes of Imperial France's foreign policy had left France internationally isolated: French support for the Polish rebellion in 1863 had broken the alliance with Russia; lack of French support to Austria during the Seven Weeks War against Prussia offended the Habsburgs; French defense of the Pope so that he could keep the Lazio had greatly angered the previously friendly Italians, who had given them their Savoy and Nice possessions, after two popular referenda, in 1860; France was also seen from Istanbul as a vulture that encouraged the Ottoman Empire's disintegration through their help to the Egyptians (who showed their gratefulness by giving permission for the construction of the Suez Canal, which was inaugurated in 1869 by Eugenia de Montijo, the Spanish-born Empress) and the Greeks, to obtain all Ottoman colonies; and, in the New World, the United States of America didn't forget neither the Imperial venture in Mexico nor the tentative support Napoleon III had given the Confederates during the American Civil War. France could only count on two great European powers with whom relations could be considered amicable: the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, immersed in the fruitful reign of Victoria I, and Spain.

Emperor Napoleon III of France.

Unfortunately, the United Kingdom was completely centered in its vast colonial empire and avoided getting directly involved in continental affairs, as well as the fact that they didn't trust Napoleon III given the manifest French pretentions of annexing Belgium and Luxembourg during the Seven Weeks War, pretentions defeated thanks to Bismarck's skillful international diplomacy; while Spain, which had been a great French ally during Isabella II's reign, was a great unknown factor for French interests after the unexpected revolution of September 1868, an event that could change the European and worldwide political balance in considerable and permanent ways.

From his personal point of view, Napoleon III was opposed to the possibility of the Duke of Montpensier accessing to the Spanish throne, either directly or through his wife. This was because such an action would complete France's international isolation and would destabilize Napoleon III's internal power in France, given that the Duke was the tenth son of Louis-Philippe I, the king that the French Emperor had overthrown in 1848, and his crowning as King of Spain would provoke the reemergence of the Orleansist movement in the Gallic nation.

French ambassador in Madrid, Mercier de L'Ostende.

Thus, Napoleon III (on his own and on his wife's advice) ordered his agents in Spain to do the impossible so that France was the first European power that heard about the scheming of the government coalition. It was then that they managed to be the first, after the Portuguese, to hear about the Iberian candidacy that would have put Fernando de Saxe-Coburgo-Gota in the Spanish throne, a candidacy Napoleon III supported because he thought that, if he did so from the start, the resulting Iberian nation from the dynastic union of Spain and Portugal would become a firm French ally.

The failure of this candidacy was a setback for the Emperor's prospects, and the rumors of the Prussian candidacy, which the French were only hearing about through the newspapers, were denied officially by the Spanish and Prussian Governments to save the candidacy. Everybody knew that France would completely reject it, so it was forbidden to let the secret negotiations reach Paris' ears, to which it helped that France had treated Spain like dirt for years, and the establishment, by the Emperor, of a great support for the Bourbon monarchy, under the new leadership of Prince Alfonso (Isabella II abdicated his dynastic rights in his only son on 25th June 1870), who was studying in Vienna while the Isabeline monarchists called him Alfonso XII. These circumstances, and the enormous disinformation effort done by the Prussian agents, undermined French efforts to know the result of the search for the new King of Spain.

French Empress Eugenia de Montijo.

However, the French ambassador in Madrid, Mercier de L'Ostende, managed to arrange a private dinner with Manuel Ruiz Zorrilla with the objective of knowing who would be the King of Spain. Dinner took place normally, with both politicians talking about trivial affairs, and when the French thought the way was prepared enough to talk about the matter, L'Ostende asked the Spaniard if Montpensier had any chances, but Ruiz Zorrilla assured him it was impossible due to his Bourbon kinship, his political leanings, his excessive ambition and his recent killing of Enrique de Borbón in a duel, although he would probably have parliamentary support from some staunch Unionists led by Admiral Topete.

Then, the French ambassador asked the Radical leader who would be in better position of gaining the required parliamentary support based on the Law of 10th June (that required an absolute majority of all Deputies to a candidacy was accepted), and Ruiz Zorrilla, who had realized which were the French ambassador's intentions, avoided the question as best as he could. Remembering the negotiations of some members of the Government Coalition, led by former Minister Pascual Madoz, to retake Amedeo di Savoia's candidacy if Leopold zu Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen's candidacy ultimately fails, he told the ambassador that the negotiations with the Italian prince were being retaken. After knowing this, the meeting ended soon after and the ambassador returned to his house, from where he would send an special delivery to Paris announcing that there would be no problems with the Spanish succession, and that the new king would probably be an Italian prince, the Duke of Aosta.

Former Minister Pascual Madoz.

Meanwhile, and without French knowledge of it, Eugenio Salazar y Mazarredo arrived to the Courts with Prince Leopold's signed acceptance on 6th July 1870. An extraordinary session of the Constituent Courts was convened for the following day with the only reason of voting who would become the new king. The voting obtained the following result:

- Prussian Prince Leopold zu Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen: 210 Deputies.

- Proclamation of a Federal Republic: 60 Deputies.

- Antoine d'Orléans, Duke of Montpensier: 21 Deputies.

- General Baldomero Espartero: 18 Deputies.

- Carlos María de Borbón y Austria-Este, Carlist Pretender: 7 Deputies.

- Infanta Luisa Fernanda de Borbón, Duchess of Montpensier: 4 Deputies.

- Proclamation of an Unitary Republic: 2 Deputies.

- Prince Alfonso de Borbón y Borbón, Prince of Asturias: 2 Deputies.

- Null or none of the above: 13 Deputies.

- Absent: 44 Deputies, including those from Cuba and Puerto Rico (18 and 11, respectively).

Proclamation parliamentary of the results of the vote of the Prince Leopold zu Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen.

With this result, the president of the Courts, Radical Manuel Ruiz Zorrilla solemnly declared

Queda elegido como Rey de los españoles el señor Leopoldo de Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen (

It has been agreed that the new King of the Spaniards is Leopold of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen) in the middle of a thunderous ovation in the chamber of the Palace of the Courts in the Carrera de San Jerónimo in Madrid.

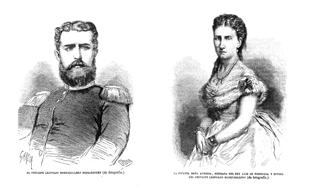

Journalistic portraits of the new Spanish kings published in Spanish and European press.

The next morning, 8th July 1870, all Spain awakened excited about the proclamation of the Prussian candidate as new King of Spain, whom the press classed him as the contemporaneous reincarnation of Emperor Charles I of Spain and V of Germany, because Leopold would represent the same feeling that deceased Charles represented on his time for Spain. However, all this popular joy explosion didn't prevent the fact that many people took the new king's surname as a joke, and due to the difficulty in pronouncing it correctly, they nicknamed him

¡Olé, olé, si me eligen! (

Olé, olé, if I am chosen!), which was acquired by those sectors opposed to his election as a derogatory nickname to Leopold's figure. Those same sectors would soon start to devise tricks that would allow them to expel the Prussian from the Catholic Monarchs' throne.

o0o0o0o0o0o0o0o0o0o0o0o0o0o0o0o0o0o0o0o0o0o0o0o

(*): The POD starts here. Eusebio Salazar y Mazarredo sent that telegram, but a strange and transcendental transmission mistake happened and the resulting telegram expressed that Leopold's acceptance would arrive in

26th July. Ruiz Zorrilla decided that he couldn't keep the deputies waiting for 18 more days (8th July had been established as the last day of parliamentary sessions before summer holidays) and suspended the sessions early. This delay derived in the affair becoming public and became soon known to the whole world, starting with French Ambassador Mercier de L'Ostende, who angrily protested to Governance Minister Sagasta. The French press and political media registered a explosion of aggressive Gallic nationalism that led to Leopold's renunciation and to the premise Bismarck used to obtain the so-long desired war against France that would allow for Germany to be unified around Hohenzollern’s Prussia, but Leopold withdrew early his candidacy and Prim managed to convince the Duke of Aosta.

o0o0o0o0o0o0o0o0o0o0o0o0o0o0o0o0o

I guess the identity of the new king isn't very surprising to readers. However, I assure you that there will be big surprises in the next update. I hope you will comment soon the progress of this alternative history.

Greetings.