Hendryk

Banned

(Link to the original thread)

This is the story of a sleeping giant that shook itself awake.

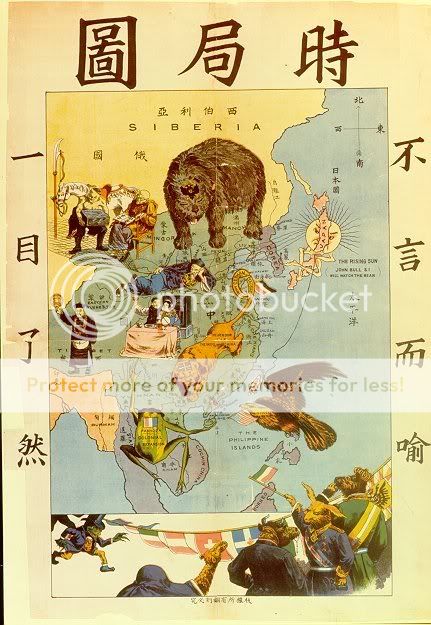

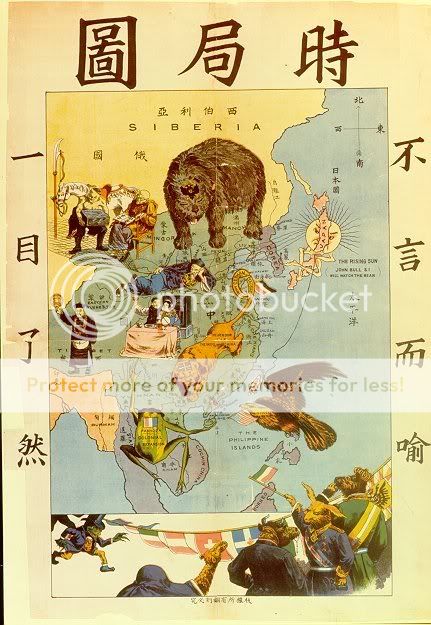

In 1911, China was called "the sick man of Asia". Its ruling dynasty was in a terminal state of deliquescence; its territory was being encroached on all sides by imperialist powers; it had lost critical elements of its sovereignty; long gone were the days when European powers respected its civilization, instead dismissing it as backwards and fossilized.

And then something happened.

******

Forgotten Achievements

From “A Revisionist Assessment of China’s Modern Political Myths” by Geraldine Brandt, Journal of Asian Studies, Volume 55:3, 1995:

That the instauration of the Qian dynasty had been a transformational moment in the history of China was conventional wisdom to such an extent that it wasn’t until the 1960s that academics would begin to challenge the claim. It was a neat, tidy, and above convenient interpretation, one that had been part of official Chinese historiography for over a half-century; that it went unquestioned in China itself was understandable enough, especially when one keeps in mind that the authoritarian nature of the regime would not be relaxed until several years into Wensheng’s reign. It is however more puzzling that even non-Chinese historians took it largely for granted all that time. The first serious revisionist attempt was that of French Sinologist Lucien Bianco in 1967, Revolution and Reform in China 1895-1947. (…)

While politically useful to the regime, the idea that the advent of the Qian dynasty in 1912 had been a turning point, before which China had been in slow but inexorable decline, and after which it began to rise again, is one that was increasingly disputed by a new generation of historians who followed into Bianco’s footsteps. The truth turns out to be rather more complicated.

The dominant interpretation is now that the Qian dynasty, to put it bluntly, got lucky; it took over at the right moment to benefit from a series of reforms that had been implemented over the past decade and a half, as well as a piecemeal modernization that, after a half-century, was finally beginning to bear tangible results. It may therefore be argued that the main achievement of the new regime was simply not to squander the fruits of its predecessor’s labor. In other words it is probable that, the alleged merits of the Qian dynasty notwithstanding, any other successor regime—including, probably, a Republican one under either Sun Yixian or Yuan Shikai—would by and large have met with a similar degree of success.

A first example concerns the field of education. While Jianguo and his indispensable prime minister Liang Qichao received credit for the thorough overhaul of the Chinese education system after 1912, the truth is that the foundations had already been laid before that. In the previous 15 years a string of reforms, some of them initiated by Kang and Liang themselves in 1898, had already begun adapting to the modern era the obsolete education system, essentially inherited from the Song dynasty and in a state of advanced decay by the end of the 19th century: the old civil service exams had been abolished in 1905; modern universities had been opened (Beijing University in 1898, Fudan University in 1905, Qinghua in 1911, and the venerable Nanjing University, originally founded in 258 CE, was converted into a modern college in 1902); and most important, the system had been rationalized along Western lines between 1901 and 1905, with a primary, secondary and tertiary levels. As far as more specifically military education was concerned, the Baoding Military Academy was up and running from 1901, churning out class after class of army officers trained to Western standards.

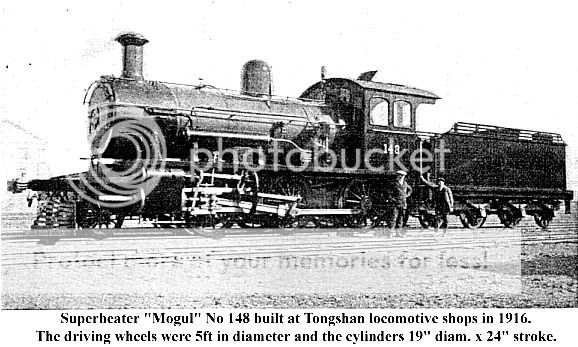

If one looks at industries, the facts tell the same story. It is often forgotten how close China had come in the 1860s from having a Meiji Era of its very own. That the Self-Strengthening Movement of the late Qing had ultimately foundered hardly means that its efforts were in vain: they laid the foundations of subsequent industrial development. Who, outside of a narrow circle of historians and weapons buffs, is today aware that the Jiangnan Arsenal, founded in 1865 by Li Hongzhang and Ding Richang, had within five years become the largest manufacturer of modern weapons in East Asia? Who remembers that, while Japan would not produce its first iron-hulled warship until 1887, the dockyards at Jiangnan were already churning out such ships as early as 1872? That until their destruction during the Sino-French War in 1884, the Fuzhou Shipyards were larger than any in Japan? That the steel foundries and arsenal set up by Zhang Zhidong in Wuchang and Hanyang respectively had by 1911 blossomed into a thriving industrial complex in Hubei province, with, among other factories, some 300 cotton-weaving mills employing a total of 12,000 workers?

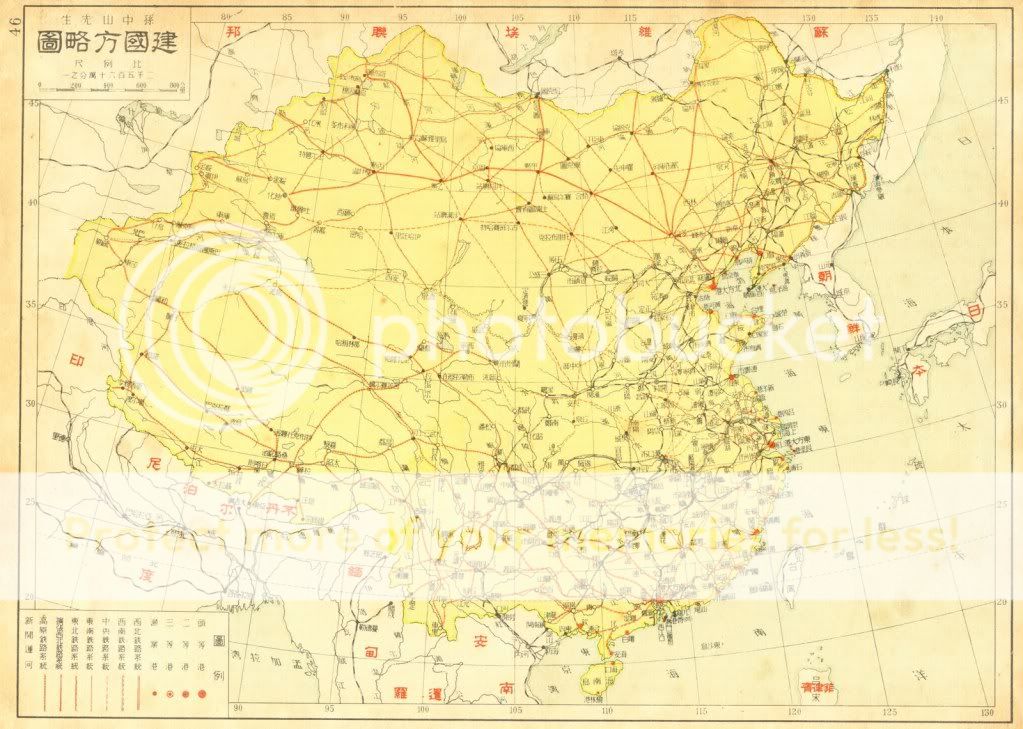

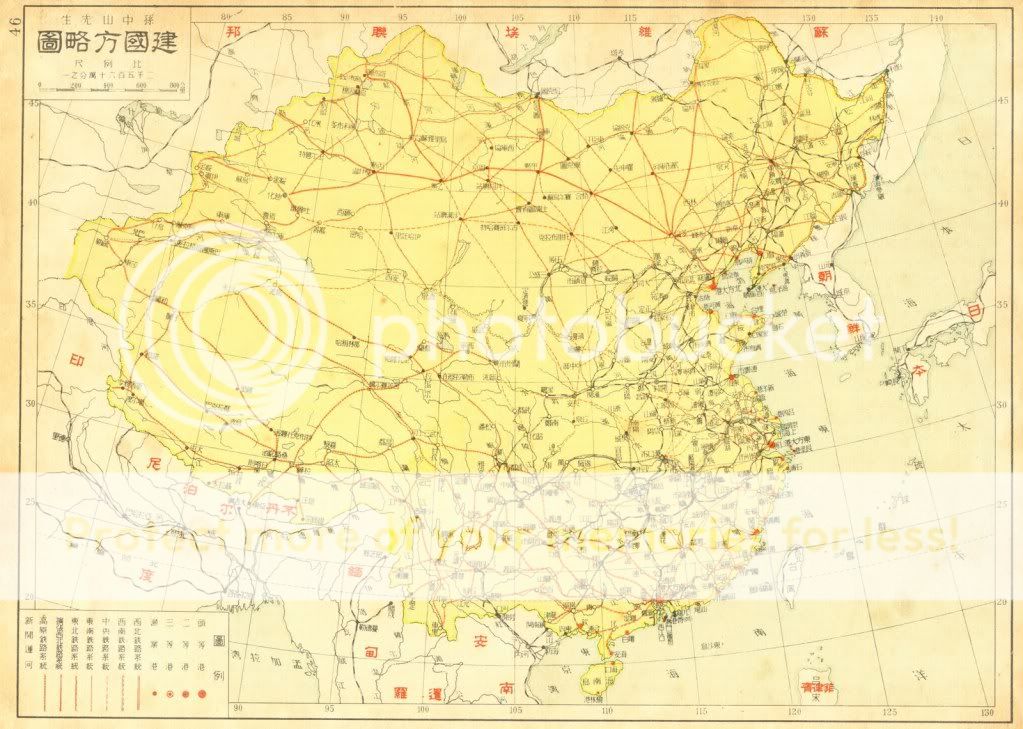

Then there is the transportation infrastructure. In 1912 China boasted a respectable 9,820 km of railroads, 30% of which were under direct government ownership; more were in the process of being laid down, and the regime change did not make a noticeable difference as far as the pace of building was concerned. It was thanks to the existence of railroads that the settlement of Inner Manchuria, mostly by peasants from Shandong, had been able to proceed so briskly in the last decades of Qing rule. After the railway from Beijing to Hankou was opened in 1905, commercial traffic in Hankou was multiplied by three in as many years. And while the intended purpose of foreign-built railroads was to make the Chinese hinterland accessible to overseas imports, they also enabled a steep rise in Chinese exports to foreign markets, with 80% growth between 1904 and 1912 (tea, cotton, soybeans, tin, etc.).

These and more achievements of the late Qing were opportunistically minimized by official historians after 1912, the better to give the Qian dynasty credit for “reversing” China’s decline and “putting the country back on the path to greatness”. But perhaps said decline had in fact already been reversed by 1912…

Excerpts from The Accidental Revolution: The Collapse of the Qing Dynasty and its Aftermath by Jonathan Spence, 1979

After Yuan’s death, it was obvious both for his former followers and for the Republicans under the leadership of Huang Xing and Sun Yixian that, unless an agreement was found for his successor, the two factions would come to blows in short order; and neither felt that it had enough of an advantage over the other to take such a chance. But who could be acceptable to both sides? Sun, who had briefly been the Republic of China’s first president, had already conceded to Yuan in the first place; Huang or any other Republican would be in no more favorable a position. The Beiyang faction, on the other hand, had only been held together by Yuan himself; with him gone, its various members seemed poised to become so many rivals, and the more lucid among them knew that if one of their number took over, he would likely turn against the others. For different reasons, the two sides therefore came to the same conclusion: a compromise figure had to be found in order to secure their respective gains.

The list of potential candidates acceptable to Republicans and Beiyang officers alike was a short one; it had to be someone with credentials both as a reformer, to placate the actors of the recent revolution, and as a conservative, to guarantee that Yuan’s former supporters would retain their preeminence. Li Yuanhong, as former vice-president to both Sun and Yuan, and since February 24 the acting president, suggested himself, but his bid was rejected out of hand by the Beiyang faction and did not receive much support from the Republicans, for whom he had all along been an ad hoc military leader, and not one seen to have the requisite political skills. They had not forgotten that he had only taken command of the revolutionary armies literally at gunpoint, after being dragged out from under his concubine’s bed where he was hiding.

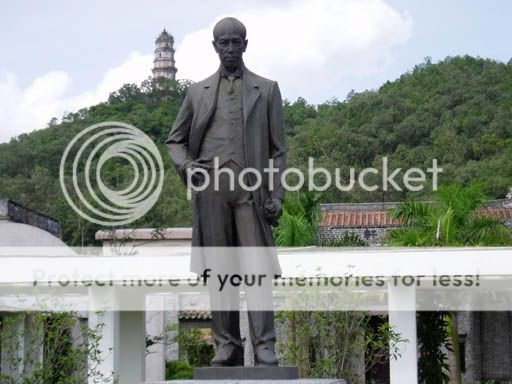

Enter Liang Qichao, who, at a still-youthful 39 years of age, already boasted nearly two decades of political activism, first as Kang Youwei’s disciple, then as a co-founder of the Baohuanghui, and most recently as a journalist and pamphleteer. Liang, formerly an outspoken supporter of constitutional monarchy, had since the death of Emperor Guangxu in 1908 moved closer to the Republican ideals of the Tongmenghui, and enjoyed the trust and personal friendship of Sun Yixian—he had at one point been his son’s private tutor. Having arrived in China a week after Yuan’s death, he was put forward by Sun and Huang as their compromise candidate. The Beiyang faction, however, was lukewarm: from their perspective Liang’s closeness to the Republicans was, like Li’s, a liability.

Statue of Liang Qichao.

The impasse was resolved when Liang met with a delegation of the most senior Beiyang officers that included Duan Qirui, Zhang Xun and Cao Kun, as well as Yuan’s closest friend Xu Shichang. Together, after a long closed-doors negotiation, they came to an agreement: the next president would be Liang’s own former mentor Kang Youwei. The onetime architect of the Hundred Days reform movement, and leader of the Baohuanghui, Kang had unlike Liang remained a steadfast advocate of constitutional monarchy, and even though he was seen as a radical a decade and a half earlier, the evolution of the political situation since then had led to his becoming perceived as something of a conservative. Xu and Zhang in particular considered him a safe fallback choice, and Liang, for his part, felt confident that he could exert critical influence even as his former mentor was ostensibly put in charge. The final arrangement was therefore that, with Kang as president, Li Yuanhong would retain the mostly ceremonial position of vice-president, and Liang would be prime minister.

That the cobbled-together arrangement failed to fully satisfy anyone is probably a reason why it worked out. (…)

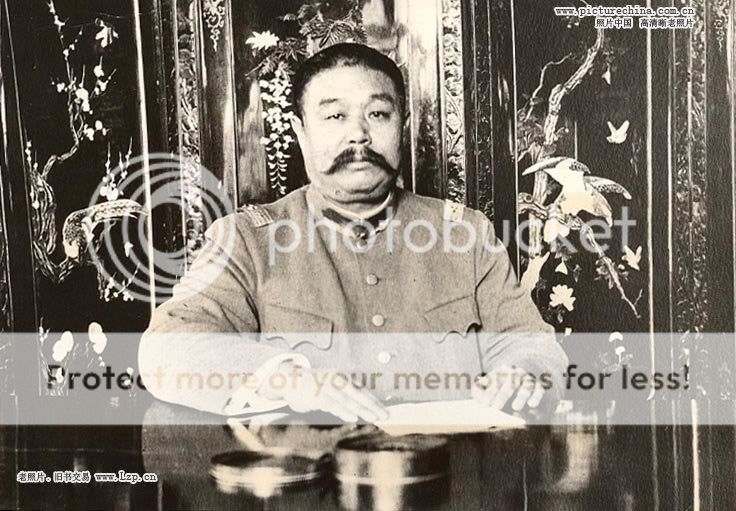

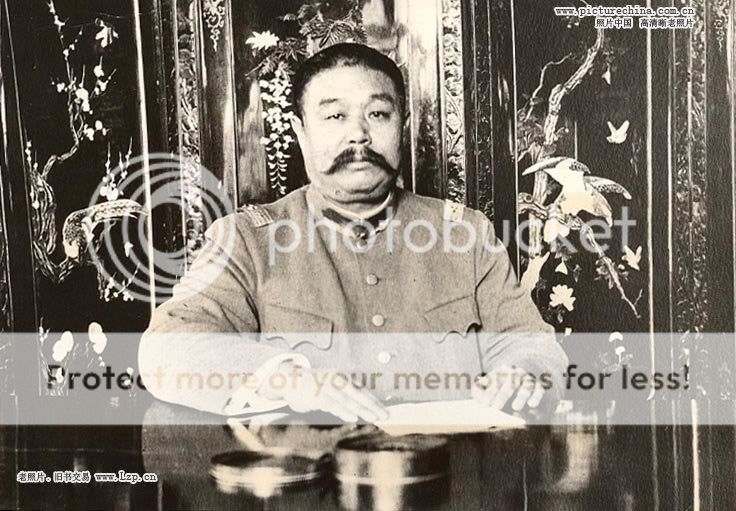

Xu Shichang.

***

The fate of the Republic of China was strangely foreshadowed by that of the Republic of Formosa, which had lasted a mere five months between May 23 and October 21, 1895—though it that case the political experiment was terminated by Japanese annexation. Formally proclaimed on January 1, 1912, the Republic of China only lasted until July 16, and went down in Chinese history books as the Interregnum Republic. In those eventful seven months, it was led by three presidents, the last one of whom went on to become emperor.

In hindsight, there never was any doubt as far as Kang Youwei was concerned that he had only accepted the position of president in order to steer the country towards imperial restoration. Certainly, however unreliable official historiography is on certain other sensitive topics, it can be trusted on the fact that Kang was not primarily motivated by personal ambition, and the disclosure of his private archives has confirmed what had been asserted by his heirs all along, namely that, had the Dowager Empress Longyu not formally abdicated on behalf of the infant emperor Puyi on February 12, he would have simply sworn allegiance to the latter and actually restored the Qing dynasty. But the abdication meant that such was not an option for this punctilious Confucian; so the only other logical choice for him was the creation of a new imperial dynasty.

But if Kang’s behavior was unsurprising even without the benefit of hindsight, Liang’s remains a topic of speculation. He had known Kang for twenty-two years and had been his faithful disciple for eighteen, so he must have been aware that his master would, given the chance, overthrow the fledgling republic. That he nonetheless suggested him to succeed Yuan Shikai as president thus implies that his ideological loyalties were at the time more fluid than Sun and the other Republicans had been led to believe. We may conclude that he was not concerned about the formal type of regime that ruled China, so long as it was one, whether Republican or neo-Imperial, that got things done. Of course, as prime minister, he was in a very good position indeed to ensure that they did get done according to his own priorities, and that he would answer to a president or a constitutional emperor was a secondary concern. In all likelihood, he merely adapted his political convictions to the new circumstances.

Sun Yixian would, in his memoirs, later claim that he was deliberately led along by Liang; a more likely hypothesis is that he had persuaded himself of Liang’s attachment to the Republican cause, and that Liang had considered opportune to not explicitly dispel the impression until the last moment. Certainly Liang does not seem to have made any openly deceitful statement, and in any case the respect he felt for Sun was genuine. (…)

President Kang and prime minister Liang had to perform a delicate balancing act when they assembled the governmental cabinet and assigned the top positions of the new regime’s structure. Enough members of the two opposite factions had to be included so that both would have a vested interest in endorsing the government, and neither would feel cheated of its spoils. Several weeks were spent in confidential negotiations before the composition of the cabinet was finally disclosed. The Republicans were given several senior portfolios, with Lin Sen named finance minister, Hu Hanmin justice minister, Huang Xing home minister, Song Jiaoren navy minister, and Sun Yixian entrusted with the custom portfolio of transportation minister (he presently set to work on a pet project of his, a plan for a radical overhaul of China’s rail network that would prove wildly unrealistic). The Beiyang faction also got its share of sensitive portfolios: Tang Shaoyi was named foreign affairs minister, Liang Shiyi communications minister, and Xu Shichang received the critical position of defense minister, while Li Jingxi became speaker of the Senate, and Duan Qirui, Zhang Xun, Cao Kun and Wu Peifu all got positions in the Chiefs of Staff Committee. Positions not attributed to either faction went to members of the Xianyuhui (the successor organization to the Baohuanghui), unaffiliated monarchists and assorted apolitical officials; Tang Hualong, in particular, became Speaker of the House.

Yang Du.

With the cabinet assembled, attention turned to the Constitutional Convention, officially convened on May 19. Kang and Liang had attributed its chairmanship to renowned legal scholar Yang Du, whose monarchist convictions were a secret to none. Although the Republicans had been initially reassured to see an American legal scholar, Frank Johnson Goodnow, invited as special advisor and vice-chairman, their hopes for a wholly new foundational document were soon dashed when it surfaced that the Convention, rather than starting from scratch, would in fact be using as a basis the unfinished draft constitution begun in 1908, which heavily borrowed from the Japanese Constitution promulgated in 1889. This sent a clear signal that the ultimate goal of president Kang was constitutional monarchy rather than the preservation of the Republic, and the timing was calculated to precipitate a clash within the Republican faction. On the one hand, the pragmatists led by Hu Hanmin insisted that the two things that really mattered were the existence of a genuine parliamentary assembly with constitutionally guaranteed prerogatives, and the presence of Tongmenghui members—themselves—at the heart of the executive where they would have the most influence; on the other, the radicals led by Sun Yixian considered the imminent demise of the Republic an unacceptable betrayal of their ideals, and called for a second revolution. Meanwhile, Liang acted as liaison between Kang and the Republicans, and offered assurances that, even though the regime was going to become technically monarchic, the essential gains of the Xinhai revolution would be preserved. In the end Sun and Song Jiaoren resigned from their respective ministries, but the others accepted to stay on. This coincided with the start of a carefully orchestrated press campaign, in which Liang displayed his sharply-honed skills as an opinion journalist, to sell the idea of imperial restoration to the politically informed public.

Frank Johnson Goodnow was invited by Kang to help draft the Chinese Constitution.

He stayed in China from 1912 to 1914, first as vice-chairman of the Constitutional Convention,

then as special advisor to its successor body the Constitutional Council.

To Song Jiaoren who was praising Sun Yixian as "the Chinese Washington", Goodnow replied:

"China doesn't need a Washington so much as a Bismarck.

Give her a Washington now, and before long she will need a Lincoln."

Sun, Song and other radical Republicans such as Wang Jingwei left Nanjing for Guangzhou where they were hoping to regroup faithful Tongmenghui elements and resume armed struggle, but upon arriving there realized that this was not a viable option: the two provinces of Guangdong and Guangxi were under the control of military governor Lu Rongting*, with whom Liang had previously struck an agreement, exchanging his loyalty to Kang against his being granted his position for life. Lu now had enough of a vested interest in the success of Kang’s scheme to oppose any Republican attempt to use his provinces as insurrectionary rear bases. After a few desultory clashes between Tongmenghui forces and Lu’s army in Guangzhou, the rebellion petered out; at Liang’s urging, Kang then issued a blanket amnesty that resulted in Sun and Song losing most of their remaining followers. They both left for Japan where they created a successor organization to the Tongmenghui, the Guomindang or National People’s Party; in time, after the reconciliation with the Republican moderates, it would become the new regime’s main parliamentary opposition.

Jianguo's Gaze pierces the Clouds, propaganda painting.

By the end of June, there no longer remained any serious political obstacle to Kang’s neo-imperial restoration; few members of the Beiyang faction cared enough to make a fuss, most being content with the positions they had been granted, and those members of the Republican faction who hadn’t been placated had now marginalized themselves. In Chinese civil society at large, although the progressive elites criticized what they perceived as a step backward, and some of the more radicalized university students staged demonstrations in Beijing and Shanghai, the general consensus was that Kang-Liang (as they were once again being referred to, in reference to the Hundred Days of 1898) deserved the benefit of the doubt. After the revolutionary fighting of 1911 and the uncertainty it brought, the country seemed stable enough. Millions of people waited for what would come next, some with misgivings, others with cautious. It would, for everyone, be something of an anticlimax.

The Constitutional Convention had not yet finished its work when Kang formally declared the instauration of the Qian dynasty on July 16, 1912, having chosen for its name that of the first trigram of the Yijing’s divination system (☰), which symbolizes vital energy at its apex. As for his own dynastic name, Kang had decided on Jianguo, “Build the Country”—as clear a statement of intent as could be; though to the Western public he would be known, inaccurately, as Emperor Kang. He wanted a Confucian ceremony in full traditional regalia, intent of respecting ritual to the letter, but Liang managed to talk him into making a number of key concessions to modernity. After the pump and circumstance, the polite revelry and the symbolic trivia of regime change had taken place, business as usual resumed both for the political class and the country as a whole. For years afterwards, government officials assigned to the more remote rural areas would come across people who had never even heard that for seven months in 1912, they had lived under a republic.

* Lu Rongting was a rather colorful figure of late Qing and early Qian China. He had started out as a highway robber who, after gathering a band of outlaws under his leadership, had become so notorious that the central government, rather than fight him, offered him a job as a military officer. By 1911, he had risen to the position of vice-governor of Guangxi, and took advantage of the revolution to set himself up as governor, and expand his de facto rule to neighboring Guangdong. Thanks to his opportunistic endorsement of Kang's imperial restoration, he became governor-for-life of both provinces.

Statue of Emperor Jianguo.

Excerpts from The Resurgence of China 1911-1945 by Lionel B. Gates, 2002

If Kang’s neo-imperial scheme was allowed to proceed with relatively little opposition, it was mostly because the national stage was no longer, at that point, the only locus of political decision-making, or even, arguably, the most important one. An important consequence of the Xinhai revolution had been the de facto devolution of many of the central government’s prerogatives to the provincial level; and so long as both the revolutionaries and the moderates who had endorsed the overthrow of the Qing (whether sincerely or out of opportunism) were allowed to retain their control over the provincial governments, what happened in Nanjing was not a fundamental concern to them.

One of the reforms implemented during the last years of Qing rule had been the creation of provincial assemblies, in response to increasingly pressing demands from progressive local elites to be given a voice in the political process. These assemblies were widely seen as inadequate, since their role was a purely advisory one, and they were deprived of genuine decision-making powers; nonetheless, they had provided a forum of expression for men eager to contribute input to the political management of their provinces. Their membership consisted, for the most part, in public officials, representatives of the landed gentry, and rich businessmen—the informal leadership of traditional Chinese society. Many of them either were Constitutionalists (in other words, they belonged to Kang Youwei’s organization) or had Constitutionalist leanings, or, out of frustration at the sclerosis of the Qing, had joined Sun Yixian’s Republican organization; and even the politically unaffiliated ones yearned for opportunities to enact badly-needed reforms. When, in October 1911, the revolution started in Hubei, and then spread to other central and southern provinces, the eviction of central rule had resulted in the provincial assemblies claiming the actual decision-making powers that they had previously been denied, including the organization and command of military forces, the collection and allocation of taxes, and the appointment of local and provincial bureaucrats. In fact, as revolutionary forces were taking over, they generally made sure to minimize administrative disruption by working together with local officials so that bureaucratic continuity was not endangered, but its control simply transferred from agents of the central government to the provincial assemblies. As Edward McCord writes,

By February 1912, the provincial assemblies had solidified their control over local government, and collectively represented a political force that could not be ignored by whoever would be in charge in Nanjing.

The Xinhai Revolution, 1911-1912.

The situation was a mixed blessing to Kang Youwei when he became the third President of the Republic. On the one hand, the fact that many provinces were now controlled by men either affiliated to his organization or sympathetic to its aims could be seen as a positive development. On the other, this spontaneous devolution meant that even after successfully sidelining the National Assembly, his nationwide rule was still constrained by the provincial assemblies, whose semi-autonomous status, even if largely informal, could act as a local check on the central government’s powers. Nor was post-revolutionary decentralization limited to civil administration: as will be explained below, the army was in much the same situation.

Kang realized that he would have to curtail the powers that the provincial assemblies had granted themselves, but that was easier said than done. He had been able to replace Republican with Neo-imperial rule precisely with the proviso that the regime change would leave lower levels of governance unaffected; were he to frontally contest the legitimacy of provincial self-rule, he would almost certainly face the very rebellion he had so skillfully avoided when he had set himself up as Emperor Jianguo. As Liang had reportedly argued, paraphrasing Laozi, “China is a fragile vase; clench it too tightly, and you may break it.” He instead advised a policy of accommodation: in exchange for the formal—and constitutionally guaranteed—recognition of the decision-making powers of the provincial assemblies, the central government would retain the prerogative of appointing provincial governors of its choosing. In essence, this arrangement replicated at the provincial level the situation at the national level, in which a prime minister (theoretically) elected by the legislative assembly shares executive power with the unelected head of state. Kang and Liang’s assumption was that, over time, administrative and budgetary creep would tilt the balance of power in favor of the governor, who would become the equivalent of a departmental prefect in the French Third Republic.

Whereas in theory, Nanjing had discretionary authority when choosing governors, in practice the choice tended to be determined by the bargaining strength of a given provincial assembly vis-à-vis the central government, which itself largely boiled down to budgetary issues: provinces in need of government help to finance local projects or to develop infrastructures—or, simply, to balance their books—were not in a position to contest a gubernatorial appointment, while those that ran surpluses or were able to operate without assistance from above got away with “suggesting” candidates that Nanjing then quietly endorsed. As a result the rule of avoidance, which until 1911 had required that governors be appointed in a different province than the one they were from in order to avoid the development of clientelist networks, was no longer consistently enforced—though it still was for public officials at the county level.

Because the relative power of provincial assemblies ebbed and flowed, a governor was not appointed for a fixed term, but until such time as the central government decided or the provincial assembly felt confident enough to press the issue of his replacement. Some of the governors appointed in 1912 served a mere three years before being reassigned, such as Li Shengduo in Shanxi and Cheng Dequan in Sichuan. One obvious exception was Lu Rongting, governor of Guangdong and Guangxi, who had been appointed for life and ruled his provinces as a quasi-potentate, using enticements and threats in equal parts to preempt any challenge to his hegemony. In Tibet, there wasn’t even a pretense of consent: when Cen Chunxuan was sent to Lhasa as governor, he arrived in a province that the Qing dynasty, as one of its last initiatives before collapsing, had put under actual military occupation; and the new regime had no intention whatsoever of allowing it to escape Chinese suzerainty.

General elections were scheduled for February 1913, based on the post-revolutionary expanded franchise (from 1% under the late Qing, the electoral body had been increased to about 8% of the population, which, while still restricted, compared favorably with the situation in Japan at the time). Ironically, while it was the Republicans who had insisted on elections since July of the previous year to strengthen their position against Kang by claiming democratic legitimacy, the timing played to their disadvantage, since the campaign took place as they were divided between the advocates of conciliation and the hard-liners. Unable to present a united front, they lost much of their political credibility with an electorate eager for order after the turmoil and uncertainty of revolutionary times. Although the Progressive Party was little more than the mouthpiece of Emperor Jianguo and his prime minister, it benefited from its perception as a cohesive force, its broad (if sometimes shallow) base of support among local elites, and most of all from the electorate’s sheer revolution fatigue: few people seriously wanted a third regime change coming on the heels of the previous two. And once again Liang Qichao proved to be a tireless, energetic campaigner. Although there is plentiful evidence that the ballot was tampered with by agents of the central government, that election paradoxically saw less resort to strong-arm tactics and intimidation than later ones in the following decades, since the apparatus of political control that the Qian would come to rely on wasn’t yet in place; despite numerous instances of ballot-stuffing and figure-cooking, the 1913 election was (if only by default) the most transparent one China would know for the next half-century. Here again, the exceptions were Guangdong and Guangxi, where cases of overt anti-Republican violence were reported, with opposition supporters beaten up by gangs of thugs or even by soldiers of the provincial army, and many voting precincts only carrying Progressive Party ballots. When the last votes were counted, only Fujian, Guizhou and Jiangxi had Republican parliamentary majorities.

However, if Jianguo and Liang’s position was now stronger, their party’s electoral victory hardly implied a mandate to reverse the post-revolutionary devolution to the provincial level: however supportive of the Qian the new assemblies were, none of them cared to renounce their decision-making powers. (…)

Jianguo and Liang were amenable to concessions with the provincial assemblies not from any sincere endorsement of political decentralization, but rather because they were not in a position to force the issue. The military option, tempting though it may have been, was not open to them, as the events of 1911 had considerably slackened the chain of command.

One should keep in mind that the Xinhai revolution had first and foremost been a military uprising. In the last years of the Qing dynasty, the deliquescent central government no longer had the organizational or financial means to proceed with military modernization, and had instead entrusted provincial governments with setting up so-called New Armies, namely armed forces trained and equipped to Western standards. Unlike the virtually-defunct Eight Banners and Green Standard armies, these new armed forces mostly recruited literate young men drawn from the middle class, as the ability to understand complex orders and follow written instructions were prerequisites; and this very characteristic had made them susceptible to political infiltration, and eventually subversion, by revolutionary activists appealing to the recruits’ nationalism and desire for progress. Unlike the several previous attempts to overthrow Manchu rule, the Xinhai revolution was successful because it used as its primary instrument the country’s very military: in the days and weeks that followed the first uprising in Wuchang on October 10, province after province had seen its New Army join the revolutionary movement. Furthermore, in order to fight loyalist forces, these armies had swollen to considerable size by hiring as many new recruits as possible, so that, by the time the Qing were formally deposed, they counted in some cases three times as many soldiers as they had before the revolution—though the new recruits were mostly ill-trained and ill-disciplined. With, on the one hand, many provincial armies under the command of revolutionary officers, and on the other, their rapid transformation into heterogeneous, bloated masses of men of dubious allegiance, by 1912 China’s armed forces were in no condition to be used by the central government in any attempt to restore centralized rule over autonomy-minded provincial governments.

Because the post-revolutionary state of the armed forces was as much a concern to the provinces as it was to the central government—overly large armies being both an unsustainable budgetary burden and a threat to social order—no time was lost in implementing a nationwide policy of disbandment, so that by the end of the year the provincial armies had shrunk back to their pre-revolutionary size, and had recovered an acceptable degree of internal discipline. Soldiers had been enticed to accept demobilization by being paid up to three months’ wages in one go upon quitting, and some of those that remained had been transferred into the newly-created national gendarmerie, and thus placed under the direct authority of the central government. The greatest resistance to disbandment came not from soldiers but from career-minded officers seeking to maintain their positions. The reduction of general troop strength prior to any elimination of military units was an adroit strategy to forestall such opposition: by decreasing the troop strength of each unit while temporarily preserving command structures, few officers' positions were immediately endangered. Those most suspect of pro-Republican sympathies were offered generous retirement bonuses, and the others were reassigned (with pay raise) to different units outside of their home provinces, in order to sever any parochial loyalties and make them more pliable to the central government’s authority.

Along with disbandment, the reorganization of the New Armies was completed by terminating the policy of voluntary recruitment and instead implementing a nationwide draft. This had both a short-term advantage to the provinces and a long-term advantage to the central government: whereas veteran soldiers were paid a comparatively high salary of 10 yuan a month, draftees would be paid six yuan a month, making the maintenance of the armed forces easier on badly-strained provincial budgets. And with the draft being on a national scale, the central government could claim control over the assignment of draftees, making sure to shuffle them from province to province, thus weakening local loyalties and strengthening a sense of national belonging. The transition, overseen by Li Yuanhong, who from vice-president had become Chief of the Defense Staff, was complete by mid-1914. To his credit, although he lacked both the credentials and the support for high political office, Li proved to be a skilled organizer. He also turned out to be remarkably good at managing the large and easily ruffled egos of staff generals, most of whom were former Beiyang Army officers and clearly intended to trade their endorsement of the new regime for all manners of favors. Keeping rivalries borne of ambition from degenerating into factionalism, while simultaneously ensuring that they wouldn’t coalize into a politically autonomous junta, was a delicate balancing act in which Li, so frequently—and unfairly—dismissed as a bumbling nonentity both by his contemporaries and by posterity, gave evidence of his political acumen.

Li Yuanhong.

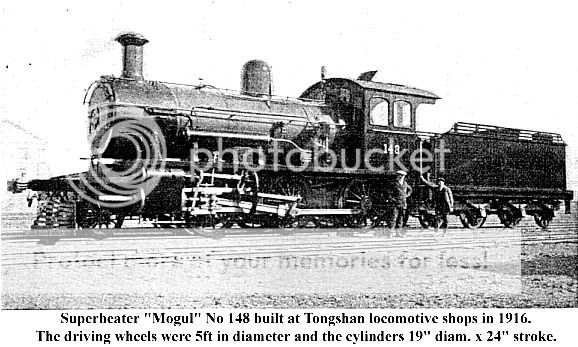

In the same spirit of incremental (some would have said creeping) military centralization, the defense ministry under Xu Shichang initiated in March 1913 a program of logistical standardization. Ever since the ad hoc creation of provincial militias by reform-minded officials during the Taiping Rebellion in the mid-19th century, the procurement of weapons and equipment by Chinese armed forces had been a decentralized one, with little concern for operational compatibility at the national level. The decision was thus taken to adopt a national standard, based on the weapons already under production in China’s main modern arsenals, chiefly those of Jiangnan, Jinling and Hanyang. The standard rifle was henceforth the Hanyang 88 (license-made version of the Gewehr 88) and the standard military sidearm the Maosi (license-made version of the Mauser M1896). It logically followed that the two standard rounds for light weapons became the 7.92 mm Mauser on the one hand, and the 9 mm Parabellum on the other. Actual implementation, however, took several years, as some of the provincial armies, out of passive noncompliance or sheer bureaucratic inertia, continued for a while to use nonstandard weapons: for example Lu Rongting had in late 1912 ordered on his own authority a large shipment of US-made Winchester M1895 rifles, which would be in use by his army until the late 1920s (and were still occasionally seen in Chinese soldiers’ hands in the early years of the Second Sino-Japanese War), while the provincial armies of Tannu-Tuva and Heilongjiang were initially issued the Russian-made Mosin-Nagant M1891 rifles, and fair numbers of French-made Lebel Mle 1886M93 rifles found their way into the inventories of Yunnan’s provincial army.

From “Salt, Silver and Land: Tax Reform in early Qian China” by Park Sunghee, Journal of East Asian Studies, Sept-Dec 2003:

Liang Qichao and Kang Youwei were aware, upon assuming power, that the financial situation of the Chinese government was dire indeed: both of them had wasted no opportunity in the previous 14 years to rail against budgetary mismanagement in general, and the tendency of the late Qing to pile on foreign debt to cover up budget shortfalls. The situation was, if anything, even more serious than they had expected.

The Xinhai revolution had not taken place in a vacuum: the rest of the world, and in particular the imperialist powers with economic and strategic interests in China, were very much involved. They had allowed the overthrow of the Qing to proceed only after being given reassurance, among other things, that the new regime, whichever form it took, would assume the debts of the previous one. First the Interregnum Republic under Yuan Shikai, and then the Qian dynasty under Jianguo, had thus from their inception been saddled with the Qing’s potentially crushing debt. China had first contracted a foreign loan in 1865 in order to pay an indemnity to Russia, but its chronic reliance on borrowing had started in earnest in 1894 to finance defense spending for the forthcoming war against Japan. After 1895, the entirety of the proceeds from China’s customs services, which had been under de facto foreign control since 1854, were earmarked for the repayment of said loans. On top of that came the payment of war reparations to Japan (230 million silver taels) and indemnities to the Eight Allied Powers following their intervention against the Boxer Rebellion in 1900 (450 million silver taels, a tremendous sum to be paid over 39 years at 4% interest). Compounding the severity of these debts, even before 1911 the central government’s tax collection apparatus had become inefficient, and with the provincial governments claiming autonomy in the course of the revolution, by 1912 very little tax money found its way to the capital any more. China stood on the verge of a spiral of ever-growing spiral of indebtedness, in which it would have to borrow money in order to repay previous loans.

On February 23, 1912, the very day before he died, president Yuan Shikai had requested a loan of seven million taels from the Four-Power Consortium in order to get the Nanjing provisional government to disband troops and to liquidate outstanding liabilities. Because of Yuan’s death, the Consortium only advanced 2 million taels on March 1st, and made it known through Tang Shaoyi, who had been Yuan’s provisional prime minister, that disbursement of the remaining amount would be conditional on a guarantee from the Chinese government that the Consortium would get preferential rights for further loans to China. This put the incoming Kang and Liang in a quandary: on the one hand, they were deeply wary of increasing yet further China’s debt to foreign lenders, who were liable to use it as a pretext to encroach some more on Chinese sovereignty; but on the other, they had no other credible option to put desperately-needed money in state coffers. Liang concluded that the money would have to be accepted to avoid complete government bankruptcy, but realized that, the decision being a politically controversial one, a backlash might result if they took it on their own—still rather uncertain—authority. So he submitted the issue to the provisional National Assembly, after arranging a meeting with Lin Sen, whom had just become finance minister, and Sun Yixian and Huang Xing, to share with them his assessment of the desperate straits of government finances. What he did not disclose, however, was that he had been privately approached by the Anglo-Belgian Syndicate (an alliance of the Eastern Bank and the Banque Belge), which had offered to make the Chinese government a secret loan if the Consortium’s offer was turned down [1]. Whether he would have taken up the Syndicate’s offer had the National Assembly voted against accepting the Consortium’s conditions remains a moot point, however, since, as he had expected, Lin, Sun and Huang convinced the Republican delegates to vote along with the Constitutionalists in favor of the loan. The National Assembly having given agreement, Liang had the legitimacy to work out the details with the Consortium. The customs revenue, completely hypothecated for the service of previous loans and the Boxer indemnity, for an undetermined time could only be a secondary guarantee; Liang therefore decided to pledge the proceeds of the salt revenue. As a central condition for floating the loan, the consortium insisted upon a measure of control over the Salt Administration, not merely advice and audit [2]. This was a stringent condition, which almost led Liang to break off negotiations despite the possible consequences. But after conferring with Kang, he understood how that particular requirement, while it outwardly constrained the central government, actually had the potential to strengthen its hand vis-à-vis the provincial governments.

Accordingly, Article 5 of the agreement provided for the establishment, under the Ministry of Finance, of a Central Salt Administration to comprise a “Chief Inspectorate of Salt Revenue under a Chinese Chief Inspector and a foreign Associate Chief Inspector”. In each salt-producing district there was to be a branch office “under one Chinese and one foreign District Inspector who shall be jointly responsible for the collection and the deposit of the salt revenues”. According to John King Fairbank and Denis Crispin Twitchett,

What Liang had done, in essence, was to outsource to foreign agents the task of collecting the revenues of a tax that the central government would, given its weakness in relation to the provincial governments, have otherwise been unable to get hold of at all. He had played two potential foes of his, foreign imperialist interests and uncooperative provincial governments, against one another, and revitalized the fiscal solvency of the central government in the process. Even though a share of the salt tax revenue went to the reimbursement of the loan, the remainder provided state coffers with a welcome injection of hard cash. In fact, the reorganization of the salt tax collection system was a boon to all concerned: in just four years, the annual yield of the tax increased more than fourfold, from $17 million to $71 million [4]. This newfound financial clout gave Jianguo and Liang the breathing space they needed to proceed with their plans.

Most of the loan had gone into clearing China’s outstanding liabilities to foreign lenders, but with the remainder, and especially with steady revenue accruing from the share of the salt tax not going into repayment, the central government was now in a much better bargaining position with the provincial ones. The provincial assemblies, it must be kept in mind, were largely controlled by reform-minded men who, although reluctant to surrender their new decision-making powers to Nanjing, shared Jianguo’s agenda of modernization. Their priorities were the construction of communication and transportation infrastructures, the development of modern industries, the spread of education, and other policies that were in tune with Nanjing’s. But in order to implement them, they needed capital, and even by retaining at their level the bulk of tax revenue instead of forwarding it to the central government, their financial capabilities were often too limited. Starting in October 1912, when the loan came through and the first effects of the new jointly-operated Salt Administration were felt, the central government was therefore able to come forward and offer to complement provincial budgets with loans of its own—which were offered with strings attached. As collateral, just as Nanjing had had to accept a degree of foreign control over the salt tax collection apparatus, it required from the provinces in need of capital that land tax collection be jointly administered between the provincial and central governments. The reasoning was that the Chinese economy, despite the embryonic industrialization undertaken since the 1860s, was still overwhelmingly agrarian; and even if agriculture generated little surplus, it was nonetheless, in aggregate terms, the main economic activity in China. To fail to adequately extract revenue from it would keep government finances dependent on comparatively marginal fiscal revenue, such as the lijin, a tax of commercial transactions introduced as a temporary emergency measure in 1853, which had since then become permanent (it would only be abolished in 1922 [5]).

In every case, the agreement explicitly spelled out that the joint administration of land tax collection would still operate to the benefit of the provincial budget, since the amount of tax revenue remaining at the provincial level would remain unchanged from that of the previous fiscal year, or the average revenue for the five previous years, whichever was higher. The deal was ostensibly offered as an initiative to increase efficiency, which indeed it was; the immediate gain for the central government was that it would, from now on, receive the share of the tax that had up to then ended up embezzled by corrupt local officials taking advantage of lax oversight, or not been duly collected in the first place due to collusion between collectors and local landlords. To that gain was added a more long-term benefit, that of an extension of the central government’s fiscal authority into a tax collection apparatus it previously had no direct control over. A National Revenue Board was created to oversee the process. As Liang put it, “The reach of the bureaucracy determines the strength of the State. The authority of our government only extends as far as an official is in place who can say, ‘This is the will of the Emperor’, and expect to be obeyed.” Within a year, eleven provinces had contracted a loan from Nanjing on these terms; and within two years, all but five of them had done so.

While this centralization of land tax collection was achieved through the back door, the idea itself was hardly a new one and had been championed as early as 1903 by no less a figure than Robert Hart, inspector-general of the Imperial Maritime Customs Service from 1863 to 1907 and one of the most influential Westerners in China:

Despite his extensive experience with Chinese fiscal matters, Hart was overly optimistic in his estimate. The actual yield of the tax in 1913 was 180 million taels [6]. Nonetheless, it was, along with the salt tax, another steady source of fiscal revenue that Nanjing could henceforth count on: between 1913 and 1931, as agricultural prices, land value and farm wages rose, revenue from the land tax increased by 67% [7].

In 1918, the young US-educated economist Huang Hanliang, who would later become director of the National Revenue Board, made in his book The Land Tax in China an assessment of the reformed system after five years of operation:

As a result partly of the 1912 “Reorganization Loan”, but especially the reform of the salt and land taxes, by 1914 China was already on a much firmer financial ground than it had been for decades. But its fortunes would improve further in the following years thanks to two windfalls, the smaller one half-expected and the larger one quite serendipitous…

* The Cambridge History of China (Volume 12)

** The I. G. in Peking: Letters of Robert Hart, Chinese Maritime Customs, 1868-1907

[1] This is OTL.

[2] This too.

[3] OTL quote.

[4] OTL figures.

[5] 1931 in OTL.

[6] This is a lower figure than the most conservative estimates in OTL, and it’s still a lot of money.

[7] OTL figure.

[8] OTL quote, except for one or two words.

From Marches of Empire: Center and Periphery in Twentieth Century China by Gaurav D. Patel, 2001

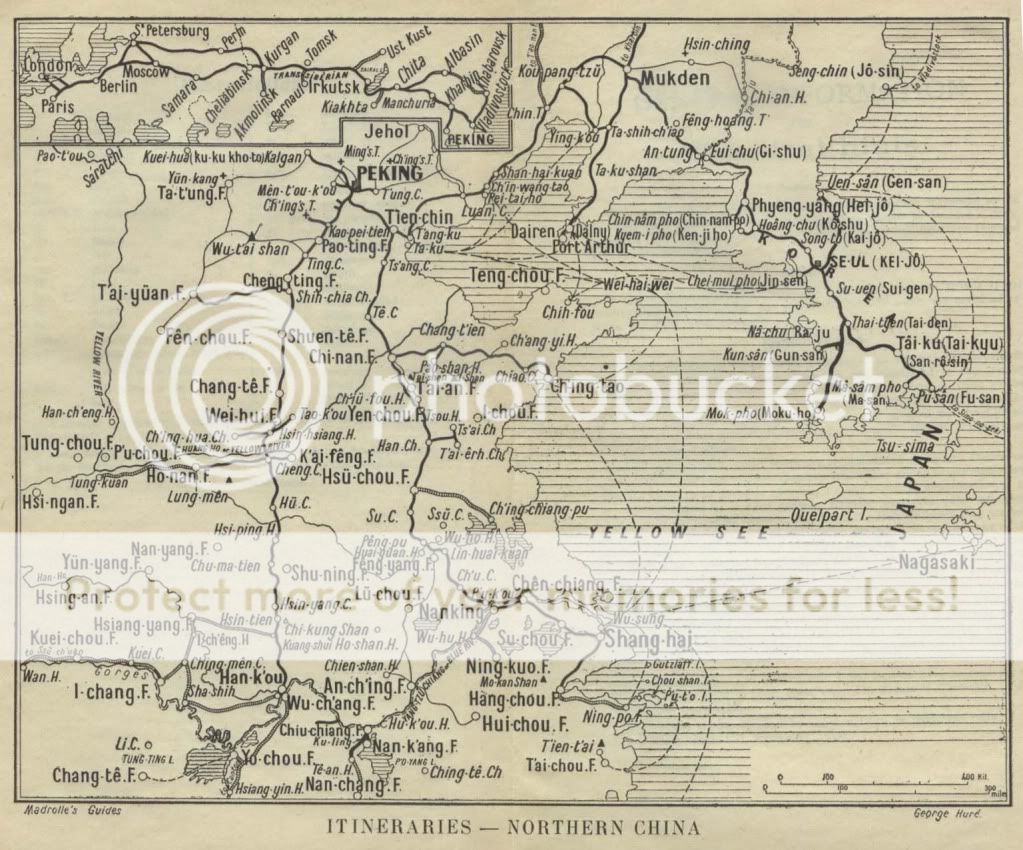

Even as they were consolidating their hold on the center, Liang and Kang were aware that they had to make sure that the periphery would not break away. The most pressing concerns were the centrifugal forces at work in Tibet on the one hand, and in Mongolia on the other. In both cases trouble came from the existence of pro-independence movements emboldened by the presence, over the border, of a potentially sympathetic foreign power—respectively Britain and Russia.

In Tibet, the Interregnum Republic had inherited from the Qing dynasty a complex situation. While Tibet’s vassalization by China dated back from the Yuan dynasty, Chinese overlordship had not been uniformly enforced throughout the centuries, depending on the priorities and the sheer strength of the dynasty in charge. The Qing had first installed an amban (imperial resident) in Lhasa in 1727, but his authority was more symbolic than real; in 1751, the Qing, while retaining the position of amban, had formally entrusted temporal as well as spiritual rule over Tibet to the Dalai-Lama. From the 1860s, Britain began taking an interest in Tibet as part of its “Great Game” against Russia for geopolitical hegemony in Central Asia. As of the time of the Xinhai Revolution, the basis for British policy in the Himalayan region was the Convention signed in 1906 between Sir Ernest Satow and Tang Shaoyi, by which Britain recognized China’s suzerainty over Tibet:

The priority for Britain when signing this Convention was obviously to preempt any Russian expansion into Tibet, there being no other “foreign state” susceptible of interfering with “the territory or internal administration of Tibet”. The principle of Chinese suzerainty was reiterated by the 1907 Convention between Britain and Russia:

Endorsing China’s claim was thus seen as the easiest way to keep Russia out of Tibet, but the tacit assumption of British delegates was that China was, in any case, too weak by that point to prevent Tibet’s de facto evolution towards internal self-rule. In this they were mistaken: in 1908, Zhao Erfeng, formerly the acting viceroy of Sichuan, was appointed amban in Lhasa and proceeded to launch a brutal campaign of repression against Tibetans in Kangba (then known to Westerners as Kham), the multiethnic buffer region between Sichuan and Tibet proper. This campaign amounted to ethnic cleansing in all but name, and it soon became obvious that the Qing intended to turn Kangba, until then unofficially considered part of Tibet, into a full-fledged Chinese province—something that was nominally achieved by the Interregnum Republic when the new province of Xikang was created. Acts of violence against civilians and monks prompted Thubten Gyatso, the 13th Dalai-Lama, to issue a protest, but Zhao’s response was to deploy troops throughout Tibet itself in February 1910; the small, ill-trained and ill-equipped Tibetan army was easily routed by Zhao’s modern forces, and a mere year and a half before the collapse of the Qing dynasty, China had reasserted direct control over Tibet. The Dalai-Lama escaped to Darjeeling via Sikkim with a small escort. As for Zhao, his attempt to quell the military uprisings that became the Xinhai Revolution resulted in his being executed by mutineers in December 1911.

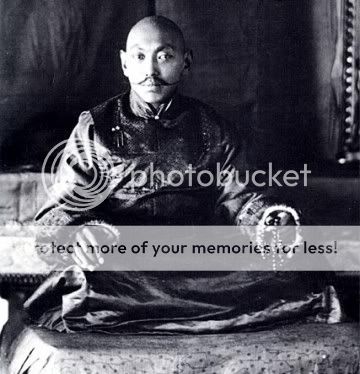

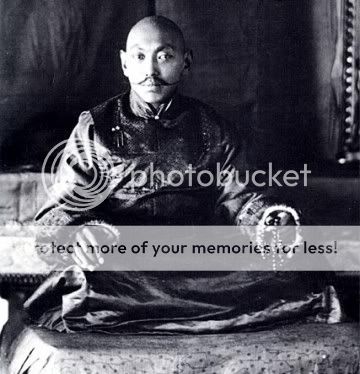

The 13th Dalai-Lama.

The situation in Mongolia was even more volatile, largely as a consequence of a change in Chinese policy during the last years of Qing rule, itself a reaction to growing Russian encroachment in the region. Indeed, until the turn of the 20th century, the Qing dynasty had allowed Mongols a significant degree of self-rule. The Manchus had initially taken control of Inner Mongolia in 1636, prior to their conquest of Beijing in 1644. Between 1655 and 1691, they gradually absorbed Outer Mongolia, and in the 1750s, they conquered the Oirats, the Western Mongols of Dzhungaria. China treated North Mongolia as a militarized buffer area largely cut off from Han colonization. Outer Mongolia’s geographical isolation north of the Gobi desert gave it a certain amount of administrative autonomy, while Inner Mongolia, located on the southern side of the desert, became closely tied to the Qing administrative system. However, China’s traditional laissez-faire attitude toward Mongol internal administration had changed in 1902, when, in reaction to growing Russian interest in Mongolia following the completion of the Transsiberian railway, the Chinese government adopted a twofold policy of centralizing the Mongol administration under that of China proper, while at the same time encouraging the Han colonization of Mongol lands. In 1911, on the eve of the collapse of the Qing dynasty, the Chinese government had decided that Inner and Outer Mongolia should be formally incorporated into China. These policies were resented by the Mongols as a threat to their traditional way of life, and this concern was compounded by the rapid rise in the years after 1902 of recently-arrived Han Chinese merchants, traders and businessmen who had taken advantage of the economic opportunities offered by the opening of Mongolia to Han settlement:

In July 1911, a group of Mongol noblemen and members of the Buddhist clergy had convened a secret meeting, and after consulting the Russian consul in the city of Ikh Khüree, had sent a delegation to Saint-Petersburg pleading for Russian assistance in restoring internal self-rule in Outer Mongolia. While some factions in the Russian government saw it as an opening for making Mongolia a Russian-aligned independent country, the prevailing view was one of moderation:

The Russian government thus intervened as mediator between the Mongols and the Qing, but as the negotiations were underway in October 1911, the Wuchang Uprising broke out and, within weeks, the dynasty was collapsing. The sudden power vacuum made not just internal autonomy but outright independence a tantalizing possibility: in November, Qing officials in Urga were driven out; on December 1, the nobles and priests of Khalkha Mongolia declared their independence; and on December 29, the Jebtsundamba Khutagtu was declared Bogd Khan. Soon the control of the Khan’s government had spread from Khalkha Mongolia throughout the entirety of Outer Mongolia. Through early 1912 the Russian government continued to offer its services as mediator, but it was increasingly obvious to all concerned that it was tempted to recognize the secessionist Mongol government and would do so unless the Chinese government regained the initiative.

A third territory that China looked set to lose to centrifugal forces as the Xinhai Revolution broke out was Tannu Tuva, then known as Tannu Uriankhai, an outlying region of Outer Mongolia proper. Formally included in the Chinese Empire by the Treaties of Kiakhta and Bura in 1727, it had been acknowledged as such by a 1869 border protocol with Russia. But in 1910 the border markers were unilaterally removed by Russia, a clear harbinger of annexationist ambitions. Russia coveted Tannu Tuva for several reasons: a growing plurality of Russian settlers; the presence of interesting natural resources, especially gold; and its location on a strategic plateau where the two sources of the Yenisei River originated, important for the defense of Siberia.

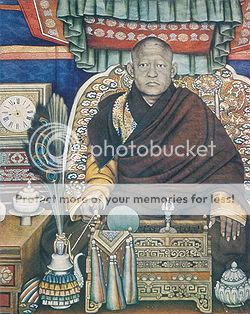

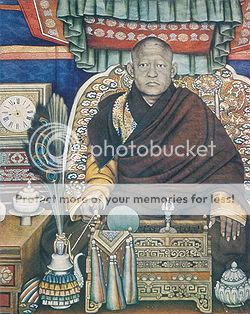

Bogd Khan.

In March 1912 the situation in both Tibet and Mongolia was thus very much in flux. Realizing that swift action was required, Liang set up the Bureau for Tibetan and Mongolian Affairs under his direct authority as prime minister, removing the question from the home ministry’s jurisdiction, much to the quiet relief of Huang Xing, who justifiably feared that the thorny issue would otherwise consume most of his attention. It is worth emphasizing that, whatever disagreements Republicans and Constitutionalists had in other regards, when it came to the preservation of central rule over China’s peripheral regions, they had exactly the same position, which explains why neither Huang nor any other Republican leader objected to Liang making Tibetan and Mongolian affairs the prime minister’s prerogative. The Bureau was the successor of the recently-disbanded Qing-era Board of National Minority Affairs, and Goingsang Norbu, a pro-Chinese native Tibetan official, was appointed as its director.

Tang Shaoyi, Liang’s incoming foreign affairs minister, who as the negotiator of the aforementioned 1906 Sino-British Convention had retained an interest in the Tibetan issue, urged him to act rapidly lest pro-independence elements gained the upper hand in Lhasa, as they already had in Urga. Liang agreed and decided to resolve the Tibetan and Mongolian issues by linking them together. Aware of British concerns over Russian expansion in Central Asia, he approached the Australian reporter George Ernest Morrison, who had in the previous years become increasingly outspoken in his defense of Chinese interests, and was famous on the Chinese political scene as an extremely well-connected figure. Through Morrison’s mediation a draft agreement was elaborated between the Chinese government and the British Foreign Office: Britain would acknowledge China’s suzerainty over Tibet on the condition that China did not “interfere in the internal administration of Tibet or station an unlimited number of troops in Lhasa or other parts of Tibet” [1], and extended the same recognition to Mongolia (as well as Tannu Tuva) with similar conditions. At the initiative of British minister plenipotentiary in China Sir John Jordan, who rightly saw that China was in a weak negotiating position, the agreement required that Chinese renounce any claims of suzerainty over Nepal, Bhutan and Sikkim (which the Qing dynasty had long claimed as vassals); that the Chinese side of the Sino-Indian border be demilitarized, with only a civilian constabulary force allowed for customs control; and that Chinese officials who had, at the time of the Younghusband intervention in Tibet, “mistreated” British officers, be demoted and sanctioned (these being Zhang Yingtang and Liang Yu). Morrison expressed reservations about the harshness of the terms, considering that the agreement would be as much in Britain’s own interest as it was in China’s, but Jordan’s calculations proved correct, and the Chinese government, in the person of its chief negotiator Wen Congyao, acquiesced to all conditions. The agreement was formalized on June 5 as the Sino-British Convention on the status of Tibet and Mongolia.

Liang wasted no time in publicizing the document in order to display his acceptance of Tibetan and Mongolian internal autonomy, thus making it possible to mend fences with the Dalai-Lama, while emissaries were sent to Urga to negotiate a repeal of the secession. Kang appointed the experienced Cen Chunxuan as the new imperial resident for Tibet; Cen picked up a contingent of reliable troops in Sichuan (where he had previously served two terms as governor) on the way, and upon arriving in Lhasa oversaw the evacuation of the Chinese troops already present, imposing strict discipline on his soldiers to avoid a repeat of the depredations committed by Zhao’s army; the reinstated Dalai-Lama returned to Lhasa, and as per the agreement, Lieutenant-Colonel William Frederick O’Connor, who had been part of the Younghusband intervention, was sent to the Tibetan capital as a British observer. In Mongolia, as a further show of good faith, Liang’s envoys offered that the government assume the entirety of the debts contracted by Mongolian noblemen and commoners alike to Han Chinese traders, a shrewd move that deflated much of the pro-independence movement’s base of support, and, to Bogd Khan, offered to give him the same status in Outer Mongolia that the Dalai-Lama had in Tibet, that of spiritual ruler with full authority in religious matters, and temporal ruler acting under the suzerainty of the Chinese government, represented by a high commissioner (a title conspicuously chosen to avoid any mention of governorship), which was to be Zhu Jiabao. The Khan added a condition of his own: that any further Han settlement be subjected to his approval. The envoys accepted, although they obtained that settlers already present as of August 1911 be allowed to stay. The resolution of Mongolia’s bid for independence also resulted in Tannu Tuva agreeing to returning into the Chinese fold on the same terms. With China’s suzerainty over both territories explicitly endorsed by Britain, Russia decided that the wisest course of action consisted in officially calling its mediation between China and Mongolia unneeded, and quietly dropping its policy of satellization of Tannu Tuva, which it had never acknowledged in the first place.

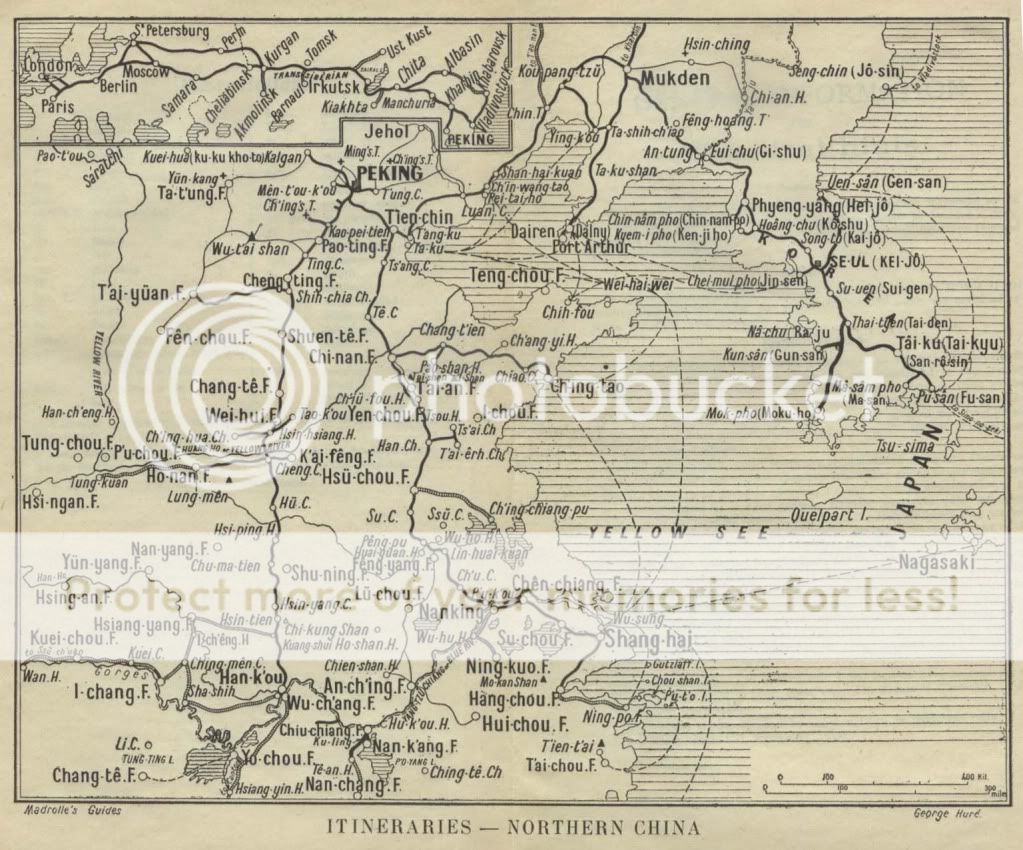

In the aftermath of Mongolia’s attempted secession, Inner Mongolia was abolished as a discrete territory and divided into the newly-created provinces of Rehe, Chahar and Suiyuan, with the remainder absorbed by Ningxia, completing the process of administrative normalization of the region begun under the late Qing. In order to tie Outer Mongolia more tightly to the rest of the country, and if need be facilitate military deployment, the Chinese government hired Zhan Tianyou a.k.a. Jeme Tien Yow, China’s most famous railway engineer, to build a railroad to Urga. A preliminary survey was conducted in early 1913, with construction beginning in October 1914. The railroad prolonged the Beijing-Baotou line to Wuyuan in Suiyuan, and from there went due north to Mandalgovi and Urga, which already had a rail link to the Siberian city of Verkhneudinsk (now Deede-Ude); it was completed by the end of 1916. A similar rail link to Lhasa was considered as well, but the project was shelved due to its unaffordable cost and its daunting technical challenges; Tibet would not be linked by rail to the rest of China until the end of the Second Sino-Japanese War.

* Stephen Kotkin and Bruce A. Elleman, Mongolia in the Twentieth Century: Landlocked Cosmopolitan.

** Ibid.

[1] This is the same offer that was made by Britain to China in OTL.

From Gloved China Hands: Westerners in the Chinese Corridors of Power, 1845-1945, by Rogeria Quartim de Moraes, 2006

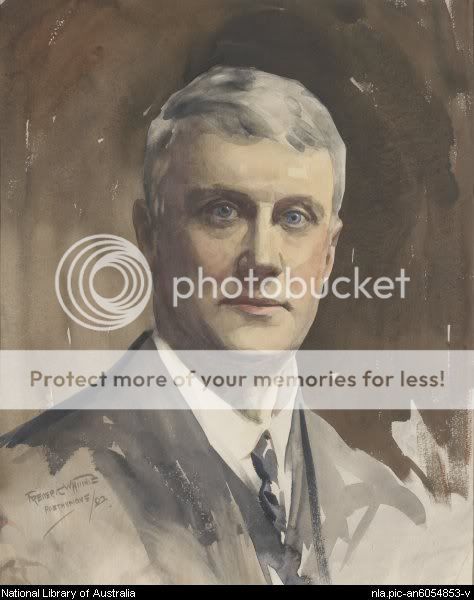

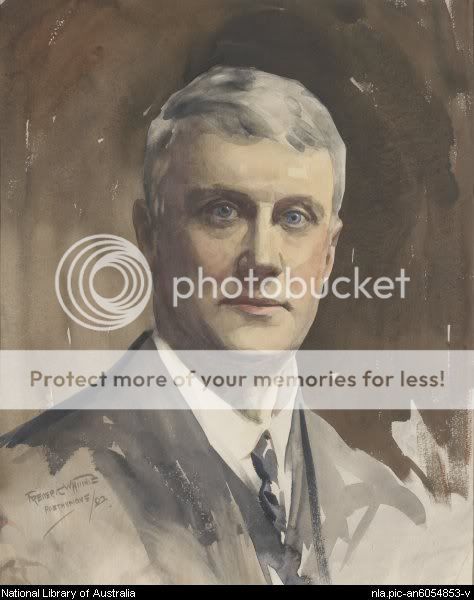

If the nascent Qian dynasty benefited from a sizeable capital of goodwill on the international stage, it owed it in large part to one man in particular, the “Canny Scot” Dr. George Ernest “Chinese” Morrison. By far the most famous Western correspondent in China at the time, and certainly one of the most famous reporters worldwide, Morrison’s role in that politically volatile period cannot be overstated. Even though his role in China’s decision to align with Entente powers turns out to have been less decisive than was then widely believed, he was instrumental in tilting international opinion in favor of Emperor Jianguo’s rule against Sun Yixian’s Republican opposition, putting his impeccable credentials and his opinion-shaping skills to the service of the new regime’s public-relations campaign. Conveniently, the idea of a Western advisor for a latter-day Chinese emperor fed into the then-widespread pop-cultural cliché of the White Man using his inherent superiority to guide well-meaning but benighted nonwhite rulers down the path to modernity, and the Chinese government cleverly used the trope to its advantage, playing up Morrison’s influence on Jianguo even in decision-making areas where, in fact, he provided but little input. Whether a good sport or, as the more radical members of China’s Republican faction accused him to be, a useful idiot, Morrison duly went along with the ploy.

So who was Morrison? To his newspaper-reading contemporaries the question would scarcely have needed an answer, as Morrison was already, in 1912, a well-known figure indeed on the international stage. Born in 1862 in Geelong, Victoria, Australia, George Ernest Morrison grew up to be a man of adventure: before beginning his superior studies at the University of Melbourne, he walked from Geelong to Adelaide, a trek of more than 950 km through largely unsettled country. Then, having completed his first year, he took a sabbatical to ride a canoe from Albury, New South Wales, all the way down the Murray River to the ocean—a trip of 2,640 km covered in 65 days. After failing his examinations, he shipped on a vessel trading the South Sea islands, and discovered his calling as a travel reporter when he started writing articles on human trafficking in the region, which earned him his first measure of fame at the ripe old age of 20 when they were published in the Melbourne daily The Age and contributed to banning the practice. Visiting New Guinea next, he had his first taste of China when he sailed on a Chinese junk on the way back; landing at Normanton, Queensland, he covered the 3,270-km journey to Melbourne entirely by foot. With sponsorship from The Age and the Sydney Morning Herald, he led an exploratory party into New Guinea; an expedition he returned from with a spearhead stuck in his body. He was sent to Edinburgh to have it removed—the delicate operation being beyond the skill of any surgeon in Australia—and there completed his medical studies. After graduating M.B., Ch.M. in August 1887, Morrison travelled to North America and the West Indies. From May 1888 he worked in Spain for eighteen months as medical officer at a British-owned mine and then resumed his globe-trotting, returning to Australia at the end of 1890. The following April he was appointed resident surgeon at the Ballarat base hospital, but he quit after two years as his wanderlust once again got the better of him. He travelled through the Philippines then up the coast of China, dressed in Chinese clothing (complete with fake pigtail).

In February 1894, he endeavored to travel from Shanghai to Rangoon, a 4,828-km journey he completed in three months; this formed the basis of his book An Australian in China: Being the Narrative of a Quiet Journey Across China to Burma, which was published to critical acclaim in Britain the following year. In the course of his trip Morrison became increasingly fond of Chinese culture and shed the remaining racial prejudice that, by his own admission, he had grown up with in Australia (although he retained a casual anti-Semitism that surfaces time and again in his private correspondence). He was however scathing in his criticism of the missionaries he encountered on the way, and commented with biting sarcasm on the wide chasm between their ambitions and the disappointing results of their evangelizing work:

Capitalizing on his rising profile, in 1897 he became the permanent correspondent for The Times in East Asia, and soon became known to the Western public as “Chinese Morrison”, a recognized authority on Chinese politics and diplomacy. As his entry by J. S. Gregory in the Australian Dictionary of Biography states,

In March 1912, Morrison was approached by the Anglo-Belgian Syndicate to privately relay to incoming Prime Minister Liang Qichao an offer for a secret loan, should the negotiations with the Four-Power Consortium for the so-called Reorganization Loan fall through. Although the offer wasn’t taken up, Liang remained in touch with Morrison, and a few weeks later called on him to help broker an agreement between his government and the British Foreign Office about the status of Tibet and Mongolia. Morrison, who was firmly committed to the preservation of Chinese territorial integrity, did his utmost to ensure a mutually satisfactory outcome to the negotiations. The British agreed to recognize Chinese suzerainty over both territories, although not without exacting stringent concessions from China which he did his best to mitigate. After the agreement went into force on June 5, a grateful Liang recommended him to then-President Kang as a private advisor.

This decision was not inspired by gratitude alone. In the months since the overthrow of the Qing dynasty, Morrison had overtly taken position for the imposition in China of a strong, centralized and if need be dictatorial government, which he considered indispensable for the modernization of the country; and like American legal expert Frank Johnson Goodnow, who had just arrived to assist in the drafting of the new constitution, he was firmly convinced that a monarchical regime was much better suited to China than a republican one. He therefore readily endorsed Kang’s project of neo-imperial restoration, and was instrumental in bringing international opinion in favor of the scheme. Morrison’s international reputation is best summarized in this article by James McPherson in the New York Times (June 11, 1912):

It must be emphasized that Morrison never saw his loyalties as going to the Qian dynasty alone: he was firmly convinced all along that, in helping China restore its power, he was also serving the interests of the British Crown. As he told Charles William Campbell (a former official at the British consulate in Beijing) in a letter:

Because Morrison never learned to speak more than a smattering of Chinese, his conversations with Jianguo required an interpret; and in order to guarantee their confidentiality, the job was entrusted to 19-year-old He Zhanli, Jianguo’s third wife (out of six), who was born and had grown up in the US. About their first meeting, Morrison wrote to William Henry Donald (editor at the Far Eastern Review):

When, in 1913, China signed the treaties that formalized its rapprochement with Britain on the one hand and France on the other, ensuring that in case of war China would join the Entente, most of the credit went to Morrison—a perception that Chinese diplomacy did its best to foster. In fact China’s decision was determined by inescapable geopolitical factors that were beyond any one man to influence: it was surrounded on every side with Entente powers or their colonies—British India to its southwest, French Indochina to its south, Japan to its east and Russia to its north. The presence of German leased territories on its coast—Jiaozhou especially—virtually ensured that even if its chose a path of neutrality, some of the fighting would necessarily take place within its borders, reiterating the humiliating situation of 1904-1905. At the time China had helplessly seen the Russo-Japanese War spill over into its Manchurian provinces, and the same could be expected to happen in Shandong were war to break out between the Central Powers and the Entente: Qingdao would simply be too tempting a target for the Japanese. As for siding with Germany, there would be little to gain in a best-case scenario, and almost certainly plenty to lose in all other outcomes, since that would give Japan, Britain’s ally, a perfect pretext for expanding its sphere of influence at the expense of Chinese territorial integrity; the option was quickly discarded. The logical solution was to enter into actual alliance with Britain and France, so that when the fight did come to Chinese shores, it would at least be on Chinese terms—and any gains would be China’s rather than a foreign power’s. Morrison’s presence had little to do with such a calculation, no matter how convenient he was as the treaties’ ostensible architect. He did however plain an undeniably crucial role, after the beginning of the war, in the creation of the Chinese Auxiliary Corps. (…)

Morrison would remain in Jianguo’s service until 1919, when he resigned for health reasons and moved to Britain.

* The Correspondence of G.E. Morrison.

** Ibid. [TTL]

From Building the Nation: Institutional Reform in Early Qian China 1912-1934 by Roderick McNeil, 2002

In its first year of existence, the new Chinese regime had focused most of its attention on the resolution of impending crises: the factional infighting between various post-revolutionary political forces, the loss of central control over autonomy-minded home provinces and secessionist outer territories, the crippling budgetary shortfall. As those were satisfactorily dealt with, from mid-1913 Emperor Jianguo and his prime minister Liang Qichao could next implement reforms they both had given a great deal of thought about since the Hundred Days Movement. Coming first on the list was the repeal of the Unequal Treaties which had been infringing on Chinese sovereignty since 1843.

There were two reasons for this choice of priorities. One was that both men, like the coalition government they had assembled out of moderate republicans, former supporters of Yuan Shikai and their own followers, were committed patriots who regarded the treaties as an insult to the Middle Kingdom and a formal admission of its semi-colonial status. The other was that they intended to play to the rising force of Chinese nationalism, reinforcing their popular legitimacy in the process. In the past two decades nationalism had proved to be a potent instrument of grassroots mobilization in Chinese society: it was by publicly protesting the Treaty of Shimonoseki that Kang Youwei had risen to national prominence in the first place; it was nationalism that had spurred the construction of the Sichuan railroad, whose botched government takeover had started the revolution; it was nationalism that had turned a ragtag secret society, the Fists of Harmony, into such a strong movement that a coalition of the eight most powerful countries in the world had been necessary to defeat it. Harnessing this groundswell of national self-awareness could make the difference between success and failure for the young Qian Dynasty, and both men knew it.

They also knew that doing so required walking a fine line between Chinese popular sentiment and foreign wariness. The foundations of the regime were still too shaky to afford antagonizing the very imperialist powers whose tacit acquiescence had made its instauration possible: were countries like Britain, France and Japan to conclude that the Qian were dangerous firebrands whom one could not reliably do business with, Jianguo and Liang knew that yet another foreign intervention was a definite threat. Consequently, they decided to attack the treaty system in a roundabout way, starting with its most visible manifestation—the grating missionary presence—while giving assurances that the protection of foreign economic interests, which were the real point of the treaties, would be safeguarded. In this they found an unlikely ally in the person of a certain venerable, highly respected British businessman.

On June 5, 1913, the visitor was welcomed with full pump as he stepped out of his train carriage in Nanjing station. The aged man, with failing hearing and fragile health, had travelled all the way from London in order to testify of his support for a controversial policy that the Chinese government was about to implement. Although a private individual, he received a statesman’s welcome, so great was his fame, and so opportune his visit. His name was Sir Hiram Maxim.

Sir Hiram Maxim in 1913.

For a half century the privileges granted to Christian missionaries by the treaties of Tianjin had been a thorn in the side of China’s patriotic consciousness. “The Christian religion,” the treaty with Britain stated in its Article VIII, “as professed by Protestants or Roman Catholics, inculcates the practice of virtue, and teaches man to do as he would be done by. Persons teaching or professing it, therefore, shall alike be entitled to the protection of the Chinese authorities, nor shall any such, peaceably pursuing their calling, and not offending against the law, be persecuted or interfered with.” The treaties signed with France and the United States contained a similar provision almost verbatim. A Chinese saying cynically summarized the situation: “When the missionaries show up, the soldiers aren’t far behind.” Indeed, foreign powers were all too eager to use the real or alleged molestation of missionaries as a pretext for gunboat diplomacy; as late as 1897, Germany had claimed rights over the Jiaozhou peninsula after the murder of two German missionaries in the region. Furthermore, missionary orders of whichever Christian denomination all claimed immunity from Chinese laws for both themselves and their local converts, and even exemption from taxes, making the Christian presence in China a point of contention and a lightning rod of patriotic indignation. It was therefore from this side that the new regime intended to undermine the treaty system.

Maxim’s support had not come out of the blue. The inventor of the modern machine gun, whose name was celebrated in song and poem (“Whatever happens, we have got/The Maxim gun, and they have not”) had for a long time been something of a Sinophile, as well as an outspoken opponent of religious proselytism. He had met Li Hongzhang, founding figure of the Self-Strengthening Movement, creator of the Western-trained Beiyang Army, and former Viceroy of Zhili, when the latter visited Britain in 1896. The two men had become friends and, in Li’s memory, Maxim had written a pamphlet, Li Hungchang’s Scrapbook, which had gone to press a mere few weeks before his visit to China. He left no doubt as to his position on what he called “a religion based on a belief in devils, ghosts, impossible miracles, and all the other absurdities and impossibilities peculiar to the religion taught by the missionaries”:

Once in Nanjing, Maxim joined forces with Jianguo’s high-profile Western adviser George Morrison—himself a vocal critic of Western missionaries in China [1]—and lent his considerable fame to the support of the new regime’s anti-missionary policies. He would spend the next ten months in China, a period during which the Western press took to calling Morrison, constitutional expert Frank Johnson Goodnow [2] and him “The Emperor’s Three Wise Men”.

Hiram Maxim (right) demonstrates his machine gun to Li Hongzhang (second from the right) in 1896.