Here's my first entry to the AH fora: hope you enjoy...

It was becoming apparent by the late 1960s that Canada’s nuclear bomber force – composed mainly of mid-1950s-vintage Canadian-built Vickers Valiants – was becoming obsolete. Although the two squadrons of Canadian Valiants had fared far better than their British counterparts, and were quite at home in their low-level attack role, it was realized that if the worst was to come to pass and the bombers were to be sent out a faster, more advanced option was required.

Valiant over CFB Cold Lake, 1958

In 1967 the newly unified Canadian Armed Forces set out a list of requirements for a Valiant replacement: the new bomber had to have a range of at least 4000 miles unrefueled, a bomb load of at least 15,000 lbs, and have a cruise speed of at least 0.9 Mach. There were few options available. The American FB-111A and French Mirage IV, while having the speed and bombload requirement, fell short on range. Britain offered Avro Vulcans which had the range and bombload, but lacked the speed requested.

The requirement languished for two years while the options were weighed. But as so often happens, the solution came from an unexpected direction. By the directive of US Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, the US Strategic Air Command had been ordered to retire its fleet of B-58 and TB-58 nuclear bombers by the end of January, 1970. Ironically, it was the specifications of the B-58 that had influenced the Canadian requirement. The USAF was already aware of Canada’s requirement and, since the Canadian Strategic Strike Force was part of the NORAD and NATO nuclear retaliatory force, the USAF made an offer to supply Canada with some of the surplus US bombers.

Canadian Ambassador to the US Edgar Ritchie, along with the Canadian Military Attaché, negotiated for the purchase of 32 of the remaining Hustlers at a cost of $2.3 Million US each, along with spares and engineering assistance. Delivery was set to begin on February 15, 1972.

The thirty-two lowest-time Hustlers (consisting of twenty-six B-58As and six TB-58As) were chosen from those placed into storage at Davis-Monthan AFB and returned to flying status. Under operation Peace Flash the Hustlers were returned to flight status and flown two at a time to Canadian Forces Base Trenton via their old home at Bunker Hill AFB, Indiana. As the Hustlers were delivered, they were moved to Trenton’s North Apron for refit, whence they would join either 419 Moose Squadron or 434 Bluenose Squadron. The refits were completed by Canadair (part of the General Dynamics conglomerate) in the North Apron hangars, installing Canadian-specific equipment and generally updating and refreshing the now-ten-year-old bombers.

The Canadian Hustler refit program consisted of three phases. Central to the Canadian update was the replacement of the J79-GE-5A engines with J79-OEL-7B engines to bring the Hustlers into motive commonality with the CF’s existing CF-104 Starfighter jets. It was realized that since they both used basically the same powerplant, updating the older -5A engines to the more powerful Canadian-built -7B engine variant was a logical decision.

The avionics changes to the CB-158 were a major improvement to the original system fitted to the Hustler, both in reduction of complexity and increase in effectiveness. The new system, based on the Mark IIB system fitted to the F-111D, consisted of 7 major components -- an inertial navigation set and attack radar built by the Autonetics Division of North American Rockwell, an IBM computer system, converter and panels by the Kearfott Division of Singer-General Precision, Inc., an AN/AVA-9 integrated display set by the Norden Division of United Aircraft Corporation, a Doppler radar by the Canadian Marconi Company, a horizontal situation display by the Astronautics Corporation of America, and a stores management set by the Fairchild Hiller Corporation. The main forward-looking attack radar of the Canadian Hustler, like the F-111D, was the APQ-130/2 with MTI and Doppler beam sharpening.

The last change was the increase in the Hustler’s mission capability. One of the ongoing weaknesses of the Hustler was its nuclear-only mission, and the Canadian Forces saw the need for conventional missions as well, as well as a reconnaissance option. Due to the Hustler’s pod design, new pods could be built to upgrade the Hustler’s operational flexibility. The pods were to be designed and built by Canadair at their Cartierville facility.

Initially, the BLU-2/B two-component pods would be used exclusively to provide the CF Hustlers with operational capability, but they were soon joined by a reconnaissance pod (similar in configuration to the MB-1C single-component pod). These pods, designated RCF in Canadian service, had three cameras located in the forward portion of the pod as well as one in the rear, and a Litton Sideways Looking Airborne Radar (SLAR) in the center-lower section. The upper pod section contained a fuel bladder double-sealed to prevent fuel leakage into the electronic areas. Twelve RCF pods were built, distributed six per squadron beginning in 1975.

The third pod type built for Canadian Hustler service was the most different from any in US service. Designed for conventional weaponry, the CWP was split internally into upper and lower halves. The upper half was fuel tankage, while the lower half consisted of a pod-length weapons bay covered by upward-sliding bay doors. When opened, the doors (2/3 the length of the pod) would extended slightly outwards and slide upwards around the circumference of the pod. The pod was stressed to carry 20,000 lbs of bombs or other weaponry. In an emergency, the doors could be ejected completely. Externally similar to the MB pods, a single ventral fin was fitted to the aft-end of the pod to increase lateral aircraft stability when the doors were opened. The existing wing-root hardpoints were also modified to allow the carriage of triple-ejector racks. After extensive testing, the CWP entered service in 1978.

The last pre-service modification made to the Canadian Hustler (and made possible by the new avionics) was the addition of an extendable refueling probe, fitted starboard of (and in addition to) the existing flying boom receptacle.

The Hustler began replacing 434 Bluenose Squadron’s Valiants at CFB Goose Bay in mid-1973. By December of that year, 434 had gained alert capability and officially entered into the joint US/UK/Canada SIOP (Strategic Integrated Operational Plan). 419 Squadron, based at CFB Namao near Edmonton, Alberta, began reequipping in 1974. At the time of squadron entry, the CB-158 was equipped with the TCP only and had as yet no conventional mission, although training for such missions was well underway. Each squadron would receive twelve Hustlers as well as three TB-58s (designated CB-158D, D for Dual-control) along with pods sufficient for each aircraft. In addition, for engineering work the Armament Engineering and Test Establishment (AETE) based at CFB Cold Lake would receive a single CB-158 as well as a CB-158D. All Hustlers were delivered by mid-1975 and the force was declared fully operational. As the Hustler force was being brought up to speed, the Valiant force was being drawn down and the venerable Valiants were placed in storage at CFB Winnipeg to await their eventual fate.

Interoperation with SAC and the British bomber force began almost immediately upon squadron service. In late 1974 a pair of CAF Hustlers made a goodwill visit to RAF Marham, and another pair visited Loring AFB, Maine. CAF Hustlers from 434 Squadron participated in the SAC “Giant Voice” bombing/navigation competition in 1976 and while they did not win, they impressed the judging panel with their performance, particularly with an aircraft only two years in service.

There were problems, however. The Mark II electronics added in the refit were experiencing the same issues as in the F-111D, primarily with the Norden primary display. The conventional-weapons pod was late arriving, and would not be in full service until 1977 at the earliest. So confident were the Canadian Forces, however, that when AMARC at Davis-Monthan put the remaining Hustlers up for scrap tender in 1976 the CAF bought an additional twenty airframes, intending to form a third squadron and have additional spares. The third squadron was destined never to form, however; instead ten airframes were brought up to service levels as possible attrition replacements (the CAF had not yet lost any Hustlers but with the B-58’s SAC accident record it was seen as a matter of time).

While the Hustler was being brought into squadron service, the AETE example was already performing development work on improving some of the B-58’s faults. Top of the list was the poor low-speed handling which made landing tricky (and sometimes fatal). To that end AETE and the National Research Council began to develop “semi-fly-by-wire” flight controls for the Hustler, as well as equipping it with an auto-land system coupled to the existing ILS. The auto-land was available by 1977, and was notable for needing no additional ground equipment: as long as the runway had a functioning ILS, the Hustler’s auto-land would be able to calculate the factors necessary to bring the Hustler to a safe landing. This was not a true “hands-off” design; instead it assisted with auto-throttles and glideslope maintenance at all weights and flight configurations. The pilot was still in charge of the aircraft at all times and saw the correct landing instructions through a new Canadian Marconi heads-up display. The auto-pilot would also “nudge” the stick and throttles as altitude decreased. This system allowed not only for easier landings in the notoriously tricky bomber, but also allowed blind landings at night or in bad weather.

In the meantime, AETE was also perfecting the Conventional Weapons Pod. While the configuration was not unusual (it was aerodynamically identical to the MB-1 Single Component Pod), problems were encountered when the bomb doors were opened. During the first supersonic open-door test, aerodynamic forces were sufficient to tear the doors off the pod. The pod was ejected almost immediately, saving the AETE Hustler. The fix came on the next test pod when spoilers were added to the pod ahead of the door openings; they would pop open 45° immediately before door opening to shield the pod-to-door gap and prevent loss of the doors at speed. After extensive testing (as has been mentioned previously), the CWP entered limited service with 419 Squadron in 1978, extending to the full fleet by 1980. The pods themselves were constructed by deHavilland Canada at their Downsview facility and were trucked to Toronto International Airport for acceptance by the Canadian Forces. Thirty pods were constructed in total; one for each Hustler along with several spare units.

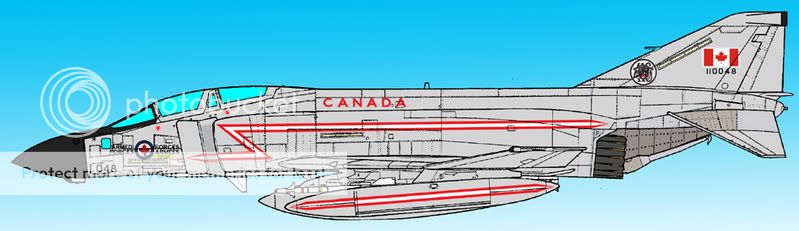

CB158 Hustler over eastern Canada, 1978

One shortcoming of the Canadian Forces that had been noted even before the entry of Hustler was a lack of in-flight refueling capacity. The aircraft themselves were able to be in-flight refueled, but apart from two drogue-equipped CC137 Husky transports there were no aircraft to do the refueling. Until the Hustler, the CAF (and the RCAF before it) had mainly relied on RAF and USAF tanker support. Although this was seen as a reasonable option, many in both the Canadian government and DND Command felt that this reliance on foreign support was not desirable and that the Canadian strategic nuclear forces should, in theory, be independent of other nations.

It was initially proposed that the surplus Valiants be used for the IFR role but the refit program was seen as being too expensive, considering the age of the Valiants and the modifications needed. Furthermore, the refit programs for the Hustler itself were turning out to be more expensive than anticipated. SAC also noted the lack of capability and, in a somewhat surprise move in 1974, offered the CAF thirty “surplus” KC-135 Stratotankers on what it termed “long-term loan”. These KC-135As, known as CC137Ks in Canadian service, were identical to USAF KC-135As apart from Beechcraft refueling pods added to the wings in a similar fashion to the already-in-service CC-137s. They would also be re-engined with Pratt and Whitney TF-33 engines to bring them into commonality with the already-existing CC-137 “Husky” transports (707-320Bs acquired from Boeing from a declined Western Airlines option). A new unit, 447 Squadron, was formed with detachments at each Hustler base for organic support.

Apart from the bases at CFB Namao and CFB Goose Bay, several Forward Operational Locations were chosen; the Hustler was still somewhat short on range and it was thought that in times of crisis it would be advantageous to base the Hustlers closer to likely targets. Although the Canadian Forces already had bases in West Germany capable of handling the Hustler, the West German government had some reservations about hosting strategic nuclear bombers. Britain did not, however, and offered the old WWII-era RCAF station at RAF Leeming as a FOL. 434 Squadron began rotating five Hustlers at a time through the RAF base in 1977.

With Europe taken care of, the Western squadron also needed a forward base.

419 was invited to lodge at Shemya AB in the Aleutian Islands; the runway there was extended both for SAC B-52s and as a courtesy to the Canadian bombers. This bse was notable as being the only base on American soil closer to the Soviet Union than the mainland United States itself.

CB158 Hustler, 1978

New Life: The Resurrection of the B-58 Hustler

It was becoming apparent by the late 1960s that Canada’s nuclear bomber force – composed mainly of mid-1950s-vintage Canadian-built Vickers Valiants – was becoming obsolete. Although the two squadrons of Canadian Valiants had fared far better than their British counterparts, and were quite at home in their low-level attack role, it was realized that if the worst was to come to pass and the bombers were to be sent out a faster, more advanced option was required.

Valiant over CFB Cold Lake, 1958

In 1967 the newly unified Canadian Armed Forces set out a list of requirements for a Valiant replacement: the new bomber had to have a range of at least 4000 miles unrefueled, a bomb load of at least 15,000 lbs, and have a cruise speed of at least 0.9 Mach. There were few options available. The American FB-111A and French Mirage IV, while having the speed and bombload requirement, fell short on range. Britain offered Avro Vulcans which had the range and bombload, but lacked the speed requested.

The requirement languished for two years while the options were weighed. But as so often happens, the solution came from an unexpected direction. By the directive of US Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, the US Strategic Air Command had been ordered to retire its fleet of B-58 and TB-58 nuclear bombers by the end of January, 1970. Ironically, it was the specifications of the B-58 that had influenced the Canadian requirement. The USAF was already aware of Canada’s requirement and, since the Canadian Strategic Strike Force was part of the NORAD and NATO nuclear retaliatory force, the USAF made an offer to supply Canada with some of the surplus US bombers.

Canadian Ambassador to the US Edgar Ritchie, along with the Canadian Military Attaché, negotiated for the purchase of 32 of the remaining Hustlers at a cost of $2.3 Million US each, along with spares and engineering assistance. Delivery was set to begin on February 15, 1972.

The thirty-two lowest-time Hustlers (consisting of twenty-six B-58As and six TB-58As) were chosen from those placed into storage at Davis-Monthan AFB and returned to flying status. Under operation Peace Flash the Hustlers were returned to flight status and flown two at a time to Canadian Forces Base Trenton via their old home at Bunker Hill AFB, Indiana. As the Hustlers were delivered, they were moved to Trenton’s North Apron for refit, whence they would join either 419 Moose Squadron or 434 Bluenose Squadron. The refits were completed by Canadair (part of the General Dynamics conglomerate) in the North Apron hangars, installing Canadian-specific equipment and generally updating and refreshing the now-ten-year-old bombers.

Refitting the Hustler: Updates and Fixes

The avionics changes to the CB-158 were a major improvement to the original system fitted to the Hustler, both in reduction of complexity and increase in effectiveness. The new system, based on the Mark IIB system fitted to the F-111D, consisted of 7 major components -- an inertial navigation set and attack radar built by the Autonetics Division of North American Rockwell, an IBM computer system, converter and panels by the Kearfott Division of Singer-General Precision, Inc., an AN/AVA-9 integrated display set by the Norden Division of United Aircraft Corporation, a Doppler radar by the Canadian Marconi Company, a horizontal situation display by the Astronautics Corporation of America, and a stores management set by the Fairchild Hiller Corporation. The main forward-looking attack radar of the Canadian Hustler, like the F-111D, was the APQ-130/2 with MTI and Doppler beam sharpening.

The last change was the increase in the Hustler’s mission capability. One of the ongoing weaknesses of the Hustler was its nuclear-only mission, and the Canadian Forces saw the need for conventional missions as well, as well as a reconnaissance option. Due to the Hustler’s pod design, new pods could be built to upgrade the Hustler’s operational flexibility. The pods were to be designed and built by Canadair at their Cartierville facility.

Initially, the BLU-2/B two-component pods would be used exclusively to provide the CF Hustlers with operational capability, but they were soon joined by a reconnaissance pod (similar in configuration to the MB-1C single-component pod). These pods, designated RCF in Canadian service, had three cameras located in the forward portion of the pod as well as one in the rear, and a Litton Sideways Looking Airborne Radar (SLAR) in the center-lower section. The upper pod section contained a fuel bladder double-sealed to prevent fuel leakage into the electronic areas. Twelve RCF pods were built, distributed six per squadron beginning in 1975.

The third pod type built for Canadian Hustler service was the most different from any in US service. Designed for conventional weaponry, the CWP was split internally into upper and lower halves. The upper half was fuel tankage, while the lower half consisted of a pod-length weapons bay covered by upward-sliding bay doors. When opened, the doors (2/3 the length of the pod) would extended slightly outwards and slide upwards around the circumference of the pod. The pod was stressed to carry 20,000 lbs of bombs or other weaponry. In an emergency, the doors could be ejected completely. Externally similar to the MB pods, a single ventral fin was fitted to the aft-end of the pod to increase lateral aircraft stability when the doors were opened. The existing wing-root hardpoints were also modified to allow the carriage of triple-ejector racks. After extensive testing, the CWP entered service in 1978.

The last pre-service modification made to the Canadian Hustler (and made possible by the new avionics) was the addition of an extendable refueling probe, fitted starboard of (and in addition to) the existing flying boom receptacle.

Into Squadron Service

Interoperation with SAC and the British bomber force began almost immediately upon squadron service. In late 1974 a pair of CAF Hustlers made a goodwill visit to RAF Marham, and another pair visited Loring AFB, Maine. CAF Hustlers from 434 Squadron participated in the SAC “Giant Voice” bombing/navigation competition in 1976 and while they did not win, they impressed the judging panel with their performance, particularly with an aircraft only two years in service.

There were problems, however. The Mark II electronics added in the refit were experiencing the same issues as in the F-111D, primarily with the Norden primary display. The conventional-weapons pod was late arriving, and would not be in full service until 1977 at the earliest. So confident were the Canadian Forces, however, that when AMARC at Davis-Monthan put the remaining Hustlers up for scrap tender in 1976 the CAF bought an additional twenty airframes, intending to form a third squadron and have additional spares. The third squadron was destined never to form, however; instead ten airframes were brought up to service levels as possible attrition replacements (the CAF had not yet lost any Hustlers but with the B-58’s SAC accident record it was seen as a matter of time).

Development and Upgrading

In the meantime, AETE was also perfecting the Conventional Weapons Pod. While the configuration was not unusual (it was aerodynamically identical to the MB-1 Single Component Pod), problems were encountered when the bomb doors were opened. During the first supersonic open-door test, aerodynamic forces were sufficient to tear the doors off the pod. The pod was ejected almost immediately, saving the AETE Hustler. The fix came on the next test pod when spoilers were added to the pod ahead of the door openings; they would pop open 45° immediately before door opening to shield the pod-to-door gap and prevent loss of the doors at speed. After extensive testing (as has been mentioned previously), the CWP entered limited service with 419 Squadron in 1978, extending to the full fleet by 1980. The pods themselves were constructed by deHavilland Canada at their Downsview facility and were trucked to Toronto International Airport for acceptance by the Canadian Forces. Thirty pods were constructed in total; one for each Hustler along with several spare units.

CB158 Hustler over eastern Canada, 1978

Refueling the Beast

It was initially proposed that the surplus Valiants be used for the IFR role but the refit program was seen as being too expensive, considering the age of the Valiants and the modifications needed. Furthermore, the refit programs for the Hustler itself were turning out to be more expensive than anticipated. SAC also noted the lack of capability and, in a somewhat surprise move in 1974, offered the CAF thirty “surplus” KC-135 Stratotankers on what it termed “long-term loan”. These KC-135As, known as CC137Ks in Canadian service, were identical to USAF KC-135As apart from Beechcraft refueling pods added to the wings in a similar fashion to the already-in-service CC-137s. They would also be re-engined with Pratt and Whitney TF-33 engines to bring them into commonality with the already-existing CC-137 “Husky” transports (707-320Bs acquired from Boeing from a declined Western Airlines option). A new unit, 447 Squadron, was formed with detachments at each Hustler base for organic support.

Locations and Basing

With Europe taken care of, the Western squadron also needed a forward base.

419 was invited to lodge at Shemya AB in the Aleutian Islands; the runway there was extended both for SAC B-52s and as a courtesy to the Canadian bombers. This bse was notable as being the only base on American soil closer to the Soviet Union than the mainland United States itself.

CB158 Hustler, 1978