Thanks all.

II

Confederation

So, granted all this disparity, why did BNA ever come together? One reason was that what they shared - especially their British heritage - was a lot bigger than it sounds today. The fact that a Newfoundland fisherman, a PEI farmer, an Ontario lumberjack, and a BC miner, were all British citizens, was seen as a much larger thing than the obvious differences, which, if not totally gone, are at least a lot less significant. Also important, especially in Canada, was the desire to make like the United States and settle the west; the mounting population pressures were making this a more important factor by the day and a united BNA would obviously be in a better position to get its hands on the boundless prairies. The British, too, were in favor of union; their view of Empire, especially the white parts thereof, was that it was a good thing to have but the less day-to-day running - and paying for - they had to do the better. A united BNA could be relied upon to do a lot more of its own running, and paying for. The larger markets of a united BNA made it popular amongst merchants and railroad investors; as mentioned above, the Grand Trunk was one of the most urgent pushers for union.

Finally, there was the United States. In the first half of the 1860s the United States had fought and won a bloody civil war, ending in the rather surprising - and even more, disquieting - discovery that the USA had suddenly become, almost without intending to, a military power to be reckoned with. At the receiving end of a century of Manifest Destiny spirit - and it was only their good showing in 1812 that had kept BNA from being treated as roughly, or worse, than Mexico - BNA found this an understandably unsettling turn of events. A unified BNA could better organize its defense, and - more pragmatically - develop enough national sentiment of its own to keep itself from simply falling into the gaping maw of the United States.

There was also opposition, however. The main opposition to union, ironically enough in light of later events in Canadian history, came from the Maritimes, not Quebec. The Canadians largely spearheaded confederation, and many in the Maritimes were concerned about being sucked into this larger union. The economic concerns of the Maritimes and Canada were quite different; indeed, almost opposed. The Maritimes based their economies on fishing and trading, and were firmly in favor of free trade, which would keep their markets open; Canada, by contrast, wanted tariffs to help sponsor their fledgling manufacturing sector. And, in a contest between Canada and the Maritimes, there was no doubt about who would win: the much larger Canadian population (and, therefore, political representation) would trample over the Maritimers’ concerns. (In the end, the Senate, unelected but assigned seats on regional lines, as in the US, was made to solve this problem.)

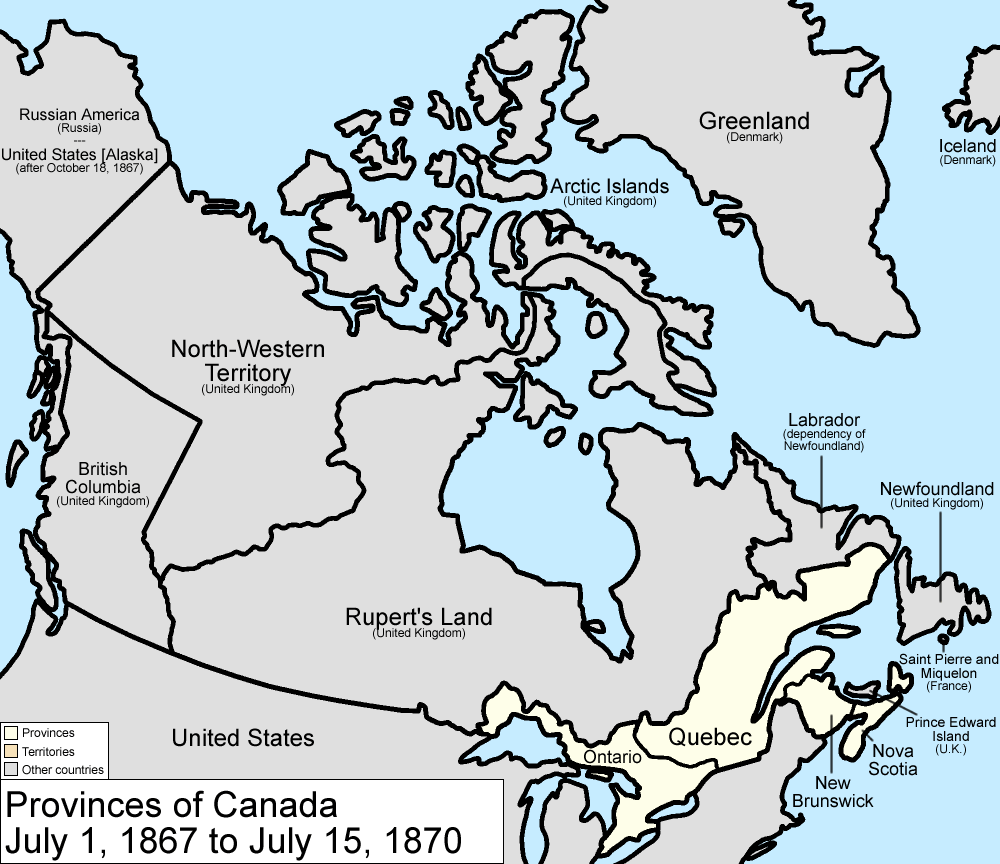

Nevertheless, Confederation was brought in – “floated in on a tide of champagne”, in one historian’s phrase. Canadian politicians, spearheaded by Canadian Premier John A MacDonald and his Quebecois partner, George-Etienne Cartier, wined and dined the Maritimers at a series of conferences, first in Charlottetown, PEI and then Quebec City, trying to convince them to get onboard. By early 1867 they had New Brunswick and Nova Scotia with them and went to London to get the British government’s assent. The British government, if anything, was disappointed that PEI and Newfoundland were not joining, but were willing to let the Canadians take the last step towards total internal self-government (and self-financing). O July 1st, 1867, the BNA Act was signed, creating the new Dominion of Canada, and granting the new federal government thus created most domestic powers. Almost immediately it began to fall apart.

As a consequence of the BNA Act, the new federal government and all four new provinces of Canada had to have a new election; in the provinces this essentially amounted to a referendum on Confederation. MacDonald, merging the pro-confederation parties of the various colonies into the new Conservative Party of Canada, managed a decisive federal victory over the disorganized anti-confederation forces, thanks in no small part to his popularity in Ontario and Quebec, where the provincial pro-confederation forces also won decisive victories. In New Brunswick as well, the pro-confederationers managed a win. Not so in Nova Scotia. Premier Charles Tupper's party, who had led Nova Scotia into Canada, was massacred in the general election, winning only 2 of 38 seats. The anti-confederation Joseph Howe became premier, and immediately began making secessionist noises. But MacDonald’s new federal government managed to talk him down; Nova Scotians got more posts in the cabinet, the province got more federal grant money, and the federal government agreed to buy more of Nova Scotia’s debt. Secessionism began almost immediately to fade as a force in Nova Scotia, although it would be some time before it went away entirely.

In Quebec, by contrast, what emotion was raised by the union tended to be uniformly pro-confederation. French-Canadian nationalism, at this time, was so marginal as to be almost invisible. Nevertheless, the regionalism of the new country was a major concern for MacDonald's new government; his efforts, and the efforts of his successors, to build a nation would fill most of the rest of the century.