You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Carrier development, during and post WWI- help

- Thread starter CarribeanViking

- Start date

It would also help if the RN had begun to develop heavier than air aviation earlier.

A possible POD is the Report of the Esher Committee published in January 1909. It said that the Army and RN should do airships instead of aeroplanes, the result being HMA No. 1 The Mayfly.

IIRC Lord Esher changed his mind a few months after his report was published and said that he should have recommended that the Army and RN buy 40-50 aeroplanes for service trials.

The RFC (Naval Wing) later the RNAS was formed in 1912. A start in 1909 doesn't mean the RNAS of 1914 ITTL have aeroplanes or aircraft carrying ships as good as 1917 IOTL because the money needed wouldn't be available. However, would give the RN 3 extra years to develop the theory of naval aviation.

This POD is too late for the first flight from a British warship to be advanced by exactly 3 years (January 1912 to January 1909). But the Hermes trials could be brought forward from 1913 to 1910. The Ark Royal could be commissioned in 1912 instead of 1915. The purchase of the Campania could also be brought forward 3 years. It would also help if her sister ship the Lucania wasn't scrapped in 1909 so that she could be acquired too.

Whether that means the RN commissions its first flush deck aircraft carrier 3 years earlier is another matter.

A possible POD is the Report of the Esher Committee published in January 1909. It said that the Army and RN should do airships instead of aeroplanes, the result being HMA No. 1 The Mayfly.

IIRC Lord Esher changed his mind a few months after his report was published and said that he should have recommended that the Army and RN buy 40-50 aeroplanes for service trials.

The RFC (Naval Wing) later the RNAS was formed in 1912. A start in 1909 doesn't mean the RNAS of 1914 ITTL have aeroplanes or aircraft carrying ships as good as 1917 IOTL because the money needed wouldn't be available. However, would give the RN 3 extra years to develop the theory of naval aviation.

This POD is too late for the first flight from a British warship to be advanced by exactly 3 years (January 1912 to January 1909). But the Hermes trials could be brought forward from 1913 to 1910. The Ark Royal could be commissioned in 1912 instead of 1915. The purchase of the Campania could also be brought forward 3 years. It would also help if her sister ship the Lucania wasn't scrapped in 1909 so that she could be acquired too.

Whether that means the RN commissions its first flush deck aircraft carrier 3 years earlier is another matter.

The purchase of the Campania could also be brought forward 3 years. It would also help if her sister ship the Lucania wasn't scrapped in 1909 so that she could be acquired too.

The RN could only purchase Campania when it did as it was going for scrap.

I haven't looked for the source, but IIRC the Admiralty subsidised the construction of Campania and Lucania so that if required they could be requisitioned by the RN and used as armed merchant cruisers. Also the Cunard Line might be glad to be rid of her in 1911-12 if the Admiralty made them a decent offer.

Admittedly that does not fit in with the Wikipaedia article on RMS Campania which says her last commercial voyage was in September 1914 when was replaced by the RMS Aquitania.

However, not having these ships available in 1911-12 might be a good thing. It might strengthen the Admiralty's case to buy a purpose built ship with the Treasury.

Admittedly that does not fit in with the Wikipaedia article on RMS Campania which says her last commercial voyage was in September 1914 when was replaced by the RMS Aquitania.

However, not having these ships available in 1911-12 might be a good thing. It might strengthen the Admiralty's case to buy a purpose built ship with the Treasury.

Yes, I was in a foul mood about that; partly because I really am stuck, not so much on the tactics and technology as the behind the scenes shouting match and wrangling for budget that will determine what actually happens.

I'll reconstruct the post in a bit- much of it was a list of what happened in OTL as a jumping off point, no less than eleven small carriers, three large although two of them almost too late.

The abolition of the R class is a result of the major fleet action both sides were expecting early in the war- in my TL, it actually happens, the High Seas Fleet attempts to intercept the BEF on it's way to France.

As a result of the casualties there sustained, by both sides, the Grand Fleet emerges with less of a need to pad the battle line out and much more of a need for fast ships- the R class are no longer necessary, and it would make sense to have a couple more R BC's.

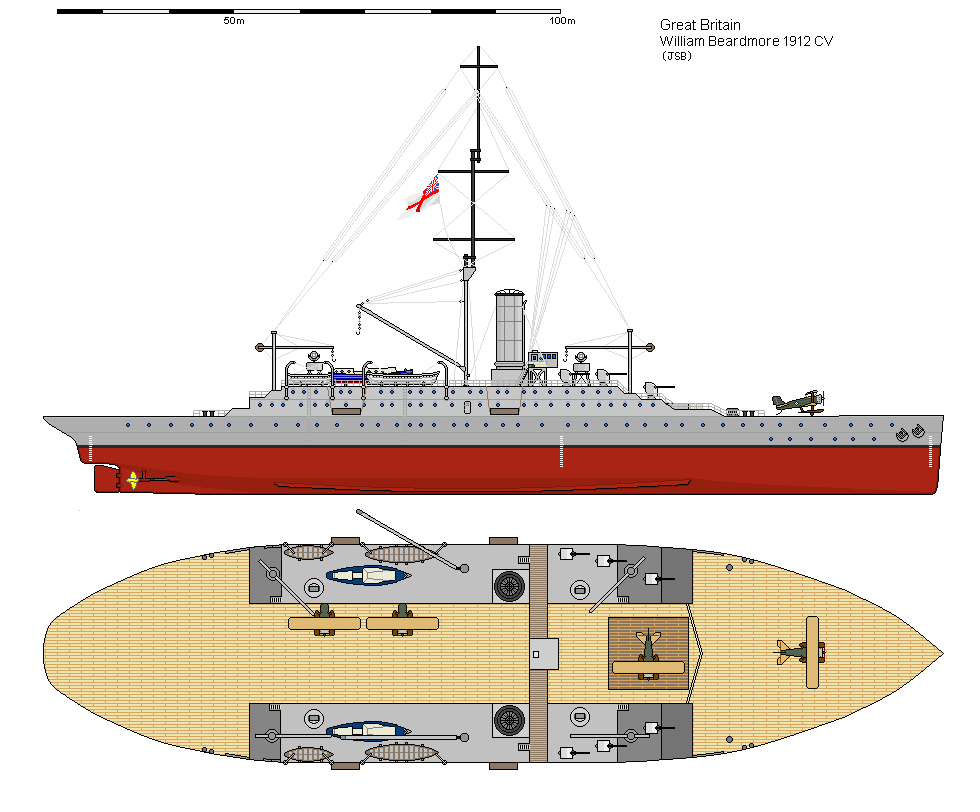

But the carriers- Beardmore's proposal, on wind tunnel testing, proved to be highly iffy, did it not? Turbulence behind the islands made it not a particularly wise proposition.

Given some interest, though, prewar exercises that go some distance to making it sound like a good idea, other conversions could be done- there are at least three ships, one rescuable from the breakers' yard for scrap value like Campania was, the Majestic of 1890, two new and not yet fully fitted out- liners Belgic and Alcantara, leaving 10CS with Alsatian for a flagship-

so in theory, the main event, the second large naval clash of the war (an attempt to break the Northern Blockade) could be attended by a full, four ship Carrier Battle Squadron, carrying sixty to seventy aircraft.

The Shorts 184 was in service at this date, had already been employed in torpedo attack in the mediterranean theatre, and made the bulk of Campania's air group in reality.

And after that, I start drooling uncontrollably. Discount the fighters and you're looking at quite a healthy carrier striking force, some fifty torpedo bombers. (I will get around to writing this up eventually, but suffice it to say that after the event, there will be another exhibit in Portsmouth Historic Dockyard.)

And then? The island style of Beardmore's is unlikely to be acceptable, but what happens to naval design and construction- of carriers and of the rest of the fleet? After the battle experience that would in our timeline only arrive in 1940, here twenty- four years early?

I have a head full of fog, and am trying not to be hopelessly overoptimistic about this.

Razee and convert some of the less useful older ships? the Monmouth class armoured cruisers were fast, reasonably long legged, and almost completely useless as gunships; but how expensive would such a conversion have been?

Build the hangar and flight deck on top of the existing structure, adding a deck, stripping the guns and using their space as a sort of U-shaped lower hangar level, for stores and parts and disassembled spare aircraft?

Come to think of it, at this point the I class dreadnought armoured cruisers, or at least the survivors, are probably no longer considered fit for the gun line.

Fisher's Follies? Would they even be completed as gunships at all, or be carriers from the beginning?

It is an excellent drawing, but the ship would have been a learning experience more than a combat vessel; historically, there is Campania, and with three others providing a mix of seaplane and landplane capability, it is an enormous leap forward that lands- where?

As tempting as it is to complete the G3's as carriers, it's a shade unlikely.

Oh, and thank you for bothering to reply, I'm just in a poor mood these days.

I'll reconstruct the post in a bit- much of it was a list of what happened in OTL as a jumping off point, no less than eleven small carriers, three large although two of them almost too late.

The abolition of the R class is a result of the major fleet action both sides were expecting early in the war- in my TL, it actually happens, the High Seas Fleet attempts to intercept the BEF on it's way to France.

As a result of the casualties there sustained, by both sides, the Grand Fleet emerges with less of a need to pad the battle line out and much more of a need for fast ships- the R class are no longer necessary, and it would make sense to have a couple more R BC's.

But the carriers- Beardmore's proposal, on wind tunnel testing, proved to be highly iffy, did it not? Turbulence behind the islands made it not a particularly wise proposition.

Given some interest, though, prewar exercises that go some distance to making it sound like a good idea, other conversions could be done- there are at least three ships, one rescuable from the breakers' yard for scrap value like Campania was, the Majestic of 1890, two new and not yet fully fitted out- liners Belgic and Alcantara, leaving 10CS with Alsatian for a flagship-

so in theory, the main event, the second large naval clash of the war (an attempt to break the Northern Blockade) could be attended by a full, four ship Carrier Battle Squadron, carrying sixty to seventy aircraft.

The Shorts 184 was in service at this date, had already been employed in torpedo attack in the mediterranean theatre, and made the bulk of Campania's air group in reality.

And after that, I start drooling uncontrollably. Discount the fighters and you're looking at quite a healthy carrier striking force, some fifty torpedo bombers. (I will get around to writing this up eventually, but suffice it to say that after the event, there will be another exhibit in Portsmouth Historic Dockyard.)

And then? The island style of Beardmore's is unlikely to be acceptable, but what happens to naval design and construction- of carriers and of the rest of the fleet? After the battle experience that would in our timeline only arrive in 1940, here twenty- four years early?

I have a head full of fog, and am trying not to be hopelessly overoptimistic about this.

Razee and convert some of the less useful older ships? the Monmouth class armoured cruisers were fast, reasonably long legged, and almost completely useless as gunships; but how expensive would such a conversion have been?

Build the hangar and flight deck on top of the existing structure, adding a deck, stripping the guns and using their space as a sort of U-shaped lower hangar level, for stores and parts and disassembled spare aircraft?

Come to think of it, at this point the I class dreadnought armoured cruisers, or at least the survivors, are probably no longer considered fit for the gun line.

Fisher's Follies? Would they even be completed as gunships at all, or be carriers from the beginning?

It is an excellent drawing, but the ship would have been a learning experience more than a combat vessel; historically, there is Campania, and with three others providing a mix of seaplane and landplane capability, it is an enormous leap forward that lands- where?

As tempting as it is to complete the G3's as carriers, it's a shade unlikely.

Oh, and thank you for bothering to reply, I'm just in a poor mood these days.

Fisher's Follies? Would they even be completed as gunships at all, or be carriers from the beginning?

That's what I sometimes do in my Alt RN of the Great War essays.

It's rather convoluted, but the pre-war Beardmore design sort of evolved into the Hermes that was eventually built by them. With a POD in 1909 the Hermes might be laid down in January 1915 instead of January 1918.

The 3 follies were laid down in Apr, May and June 1915. So if you have a POD in 1909+an effective naval staff by middle 1900s+Fisher on the side of the aircraft carrier supporters if is possible that 3 larger and faster Hermes class might be built in place of Courageous, Glorious and Furious.

hope you don't mind me resurrecting it ?

Carrier development, during and post WWI- help

Right, I need a bit of help figuring out what is both feasible and likely in a given set of AH circumstances.

PoD is 1910, the somewhat belated forming of a naval general staff within the RN, and much more active fleet exercises 1911-1914, wringing out some of the kinks likely to occur with the new warfare.

Much submarining and antisubmarine work, mining and minesweeping- and aviation.

This, for reference, is what was achieved historically, before the carriers as we know them;

Aircraft and Seaplane Carriers

Hermes, Highflyer class cruiser used for seaplane trials- 5,600t, 372x54x22ft, crew 450, 20kt, 11x6", 2x18"TT, 1.5-3" curved deck, 3 seaplanes (trials 1913)

Engadine (Aug 1914); 1,676t, 316x41x16ft, crew 250, 21kt, 4x 12lbr 3", 6 seaplanes

Empress (Sep 1914); 1,694t, 323x41x15ft, crew 200, 18kt, 1,355nm at 15kt, 4x 12lbr 3", 4 seaplanes

Riviera (Nov 1914); 1,850t, 316x41x14ft, crew 250, 20.5kt, 860nm at 10kt, 2x 4", 4 seaplanes

Ark Royal (Dec 1914); 7,080t, 366x50.85x18.75ft, crew 180, 11kt, 3,030nm at 10kt, partly sail driven, 4x 12lbr 3", 8 seaplanes

Anne (Jan 1915); 4,083t, 367x47.6x27.3ft, crew 90, 11kt, 1x 12lbr 3", 2 seaplanes

Ben-My-Chree (Mar 1915), 3,888t, 375x46x16ft, crew 250, 24.5kt, 4x12lbr 3", 6 seaplanes

Campania (Apr 1915)- converted liner, 20,570t, 622x65x28.5ft, crew 600, 19.5kt, 6x 4.7", 1x 3"AA, 12 landplanes, flying off platform- machinery too old to reward further refit to flush deck

Raven II (June 1915); 4,706t, 394.4x51.5x27.5ft, 10kt, 6 seaplanes

Vindex (Oct 1915); 2,950t, 361.5x42x13.7ft, crew 218, 23kt, 995nm at 10kt, 4x 12lbr, 7 landplanes, platform

Manxman (Apr 1916); 2,048t, 341x43x16ft, crew 250, 21kt, 2x 4", 8 seaplanes

Nairana (Aug 1917); 3547t, 352x45.5x15ft, crew 278, 20kt, 2x 12lbr, 2x 12lbr AA, 7 landplanes

Pegasus (Aug 1917); 3,315t, 332x43x15.8ft, crew 258, 20kt, 1,220nm at 20kt, 4x 12lbr 3", 9 landplanes

Argus (Sep 1918, converted merchant capture); 14,450t,565x68x22ft, crew 495, 20kt, 3600nm at 10kt, 4x 4" AA, 2x 4" LA, 15-18 landplanes, full decked

Vindictive (Oct 1918, mod Hawkins class); 9,934t, 605x55x17.5ft, crew 700, 29.75kt, 5,400nm at 14kt, 4x 7.5" mk VI, 6x 21" TT, 3-2"belt, 1" deck, 12 landplanes

This was the experimental work done, and the starting point; a motley collection of small liners, cross channel ferries, coal and banana boats, converted cruisers, improvisations. All OTL.

Beardmore's yard, Govan, had proposed something almost recognisable as a modern carrier as early as 1912, and actually were responsible for Argus' conversion. She, however, was just a bit late for the war.

With more extensive trials before the war, it would seem reasonable to have more larger craft taken up for service, some of the armed merchant cruisers that briefly mushroomed in the navy list would be fair candidates.

many of the ships that were taken on were released back to civilian service soon after or converted again to troopships, there being no real combative role for them; the most seaworthy and economic were retained to form Tenth Cruiser Squadron, the northern blockade force.

There are probably a couple in there that can be spared- there was another old ship, Majestic (would require renaming to avoid confusion with the predreadnought BB), and two newer craft, the liners Belgic and Alcantara (which was actually the 10CS flagship, but they still have Alsatian so what the hell), which are either rescuable from the breakers' yard for no more than scrap value, or so new as not to be properly fitted out yet and easily convertable.

No, not at all, saves me having to remember what I typed.

With reference to HMA no.1 and the diversion to lighter than air- remember the Sea Scout class non- rigids? There were about a hundred and fifty of them, seventy thousand cubic foot capacity, plus forty and more under construction of the hundred and seventy thousand foot C (Coastal) Class. They played a major part in @ anyway, and their patrol endurance and presence is going to be hard to ignore or do without.

Now if only there was some way to sweep mines from them, but that may be technically unfeasible.

Anyway, rigid airships- I reckon there is a genuine window of opportunity for them, while they still have a competitive edge before being overtaken by advancing aviation, and that is about the first two thirds of the first world war. By the time you're looking at Albatros D.V's, Camels and SE.5a's, they're no longer worth the risk as weapons of war- and killing enemy scouts is going to be a major role for the fighter component of carrier aviation.

Non- rigids are light and cheap enough that they're worth the hazard, at least into the twenties. (There was an anecdote- one definition of blimp is said to come from "Two types of lighter than air craft; a)rigid and b)limp;" the other being that when you flick the fabric of an inflated nonrigid, it makes a noise like "blimp."

A Sea Scout based on a warship- how much of a hazard would that be? The hydrogen manufacturing plant, now that could go spectacularly wrong.

A though, for aircraft- seaplanes- based on gunships, on the battle line, it might be a better idea instead of carrying them on flying off platforms to treat them as ship's boats; seems a more reasonable extension of existing doctrine without paralysing half the main armament.

Part of the spotting top issue, their being in the wrong place, was to preserve existing arrangements for boat handling, though. Exactly the sort of misplaced priority that a staff system should serve to correct, although a little late in that specific case.

As far as I remember from DK Brown without looking it up, the wind tunnel trials on the Beardmore plan were done in 1917- actually during the war. Either that or 1922.

Campania was not, as said, the only ship going for scrap at the time; but anything obtained on those terms would have a short service life, being already nearly worn out, and be more than half experimental testbed to serve the next, newer-conversion or purpose built generation;

borrowing ships that would otherwise have been fitted out as AMC's for Tenth Cruiser Squadron seems a reasonable interim solution, how were those ships meant to be paid for anyway? There is time and energy being used on them in any case.

(What I actually had roughed out was one of the older ships completed as seaplane, one as landplane carrier, one each of the newer ships too; use the older ships as testbeds, scrap them at the end of the war, rebuild the newer hulls as necessary with the theories and ideas evolved from the older craft. Or is that too sensible?)

Rendering most of the R class unnecessary frees up yard space and workforce that could go to- many things, some of it to the carrier program, much of it to small craft and escorts more likely.

With reference to HMA no.1 and the diversion to lighter than air- remember the Sea Scout class non- rigids? There were about a hundred and fifty of them, seventy thousand cubic foot capacity, plus forty and more under construction of the hundred and seventy thousand foot C (Coastal) Class. They played a major part in @ anyway, and their patrol endurance and presence is going to be hard to ignore or do without.

Now if only there was some way to sweep mines from them, but that may be technically unfeasible.

Anyway, rigid airships- I reckon there is a genuine window of opportunity for them, while they still have a competitive edge before being overtaken by advancing aviation, and that is about the first two thirds of the first world war. By the time you're looking at Albatros D.V's, Camels and SE.5a's, they're no longer worth the risk as weapons of war- and killing enemy scouts is going to be a major role for the fighter component of carrier aviation.

Non- rigids are light and cheap enough that they're worth the hazard, at least into the twenties. (There was an anecdote- one definition of blimp is said to come from "Two types of lighter than air craft; a)rigid and b)limp;" the other being that when you flick the fabric of an inflated nonrigid, it makes a noise like "blimp."

A Sea Scout based on a warship- how much of a hazard would that be? The hydrogen manufacturing plant, now that could go spectacularly wrong.

A though, for aircraft- seaplanes- based on gunships, on the battle line, it might be a better idea instead of carrying them on flying off platforms to treat them as ship's boats; seems a more reasonable extension of existing doctrine without paralysing half the main armament.

Part of the spotting top issue, their being in the wrong place, was to preserve existing arrangements for boat handling, though. Exactly the sort of misplaced priority that a staff system should serve to correct, although a little late in that specific case.

As far as I remember from DK Brown without looking it up, the wind tunnel trials on the Beardmore plan were done in 1917- actually during the war. Either that or 1922.

Campania was not, as said, the only ship going for scrap at the time; but anything obtained on those terms would have a short service life, being already nearly worn out, and be more than half experimental testbed to serve the next, newer-conversion or purpose built generation;

borrowing ships that would otherwise have been fitted out as AMC's for Tenth Cruiser Squadron seems a reasonable interim solution, how were those ships meant to be paid for anyway? There is time and energy being used on them in any case.

(What I actually had roughed out was one of the older ships completed as seaplane, one as landplane carrier, one each of the newer ships too; use the older ships as testbeds, scrap them at the end of the war, rebuild the newer hulls as necessary with the theories and ideas evolved from the older craft. Or is that too sensible?)

Rendering most of the R class unnecessary frees up yard space and workforce that could go to- many things, some of it to the carrier program, much of it to small craft and escorts more likely.

If its of any use. This the aircraft carrier section from a Royal Navy in the Great War essay I started in October 2012.

1) Aircraft Carriers

a) Pre-War Developments

In the real world the Royal Navy did not begin to develop heavier than air aviation until 1912 but still completed the first through deck aircraft carrier in the closing weeks of the Great War. However, this might have been achieved even earlier had more money been available before the war and if there had been fewer restrictions on carrier building during it.

In the real world an aeroplane was flown off from a platform fitted to the deck of the pre-dreadnought battleship HMS Africa in Sheerness harbour on 10.01.12 and further trials were made from the battleship Hibernia and armoured cruiser London while at sea. Sueter was appointed Director Air Department (DAD) in July 1912 and he issued a specification for a 10 knot carrier fitted with a 200ft flying off deck and in October 1912 he asked Beardmore to submit a design for a 21 knot carrier.

Winston Churchill who was First Lord of the Admiralty authorised the construction of a merchant ship in October 1912, but as there were insufficient funds in the 1912-13 Estimates the 2nd class protected cruiser Hermes was proposed. It was also proposed that Beardmore build a 15 knot carrier (a variant of the original design) to pioneer flying from her deck, which would become a destroyer depot ship once she had gained data for the fleet carrier. This ship wasn’t built, but did form the basis for later Air Department fleet carrier designs.

Hermes conducted trials in 1913. Her captain said that extemporised carriers were of little value. Furthermore seaworthy seaplanes were heavy and needed long decks to take off. Thus the Air Department sought a carrier which could fly seaplanes from a long deck. However, it was 1916 before it had one.

Churchill then allocated £110,000 in December 1913 for the merchant ship conversion and planned to order the bespoke “aeroplane ship” in the 1915-16 Estimates and have it completed by the end of 1916. However, once again the money wasn’t available in the 1913-14 Estimates and only £80,000 could be provided in 1914-15. Worse the fast fleet seaplane carrier had to be put back to 1916-17 and would not reach the fleet until the end of 1917 at the earliest. Meanwhile the merchant ship conversion, HMS Ark Royal was commissioned in December 1914.

In this version of history I want to say that there was enough money for the merchant ship conversion authorised by Churchill in October 1912 and given top priority so that Ark Royal was ready to take part in the 1913 manoeuvres, but because she was not fast enough to operate with the fleet the cruiser Hermes was still given a temporary conversion.

The results were that the seaplanes carried by Hermes were often unable to take off from the sea and she was not fast enough to catch up with the fleet after stopping to launch and recover her aircraft. Ark Royal meanwhile could launch her aeroplanes and seaplanes from her deck faster than Hermes could because there was no need to stop and hoist out.

Ark Royal successfully flew off aeroplanes and seaplanes from her deck during the second half of 1913, which is nearly 3 years before the same was done by Campania in the real world. Furthermore aeroplanes were successfully landed on. This was dangerous because of the turbulence created by her superstructure, but proved that landing on was feasible. The landings and take-offs were made in sea conditions that prevented seaplanes from taking off and landing, plus Ark Royal was able to launch and recover her aeroplanes more quickly than Hermes could seaplanes.

Although this is wishful thinking it is perfectly feasible. The findings were used to prepare the staff requirements for what had become known as the Fleet Aircraft Carrier to be ordered in the 1915-16 Estimates. However, the outbreak of the Great War in August 1914 led to her order being placed 6 months earlier than planned with a projected completion date of 1st July 1916. This ship that was built was the aircraft carrier HMS Hermes of the real world.

b) Wartime Developments

Progress in the real world during the war was at first held back because the war was expected to be a short one. In August 1914 all ships that could not be completed in 6 months were cancelled or suspended. On 30.10.14 the Admiralty decided that the war would not end until the end of 1915, which allowed more ferry conversions, but not the building of new carriers. On xx the end of the war was put back to the end of 1916, but once again it did not allow enough time to build new carriers. It was not until January 1917 that the war Cabinet asked that planning be on the basis that the war would continue until at least the end of 1918. However, by then merchant shipping losses had become horrendous and priority had to be given to new merchant ships and escort vessels. Thus the ships ordered in the second half of the war took longer than intended to build.

In this version of history the 6-month rule was still introduced in August 1914, but as I have already said the new aircraft carrier was made a special case and accelerated. However, in this version of history the Admiralty later accepted Kitchener’s opinion that that the war would last at least 3 years and in xx made allowed the construction of ships that would not be ready until 1918. Finally the earlier introduction of convoys reduced merchant shipping losses to the level that the Admiralty could cut merchant shipbuilding and increase naval shipbuilding.

In the real world Hermes was converted back to a seaplane carrier in August 1914, but was sunk by a U-boat soon afterwards. No more cruisers could be converted because they were needed for other duties and only one liner was available because the others were earmarked for conversion to armed merchant cruisers. The liner was the Campania, but her machinery was unreliable due to her age and her conversion was not completed until May 1915. Meanwhile 3 train ferries were converted along the lines of Hermes in August 1914 and from October of that year they made a number of air raids on German naval and zeppelin bases. With one exception these raids failed because the seaplanes were unable to take off.

In this version of history Campania and the ferries were still the only ships available for conversion. However, in this version of history they were converted to the standard of their second refit, i.e. with flying off decks (which were long enough to launch aeroplanes and seaplanes) and steel hangars, rather than the canvas ones initially fitted.

This meant the ferries weren’t ready until January 1915, but they were much more successful because every serviceable aircraft was able to get airborne. Seaplanes were used initially, but they were soon replaced by aeroplanes, which could carry more bombs. It was found that aeroplanes fitted with flotation bags were safer for the crews than seaplanes and no more wasteful because seaplanes usually capsized and damaged beyond repair on landing.

In this version of history the liner Conte Rosso was purchased in August 1914 instead of August 1916 and completed by the end of 1916 or earlier if given higher priority. Consideration had also been given to completing the liner Gulio Cesare as a carrier, but in the real world the resources were not available. In this version of history the resources were available and she was ready by the end of 1916 if not sooner. I usually say that the Almirante Cochrane was completed as a battleship, but if purchased in January 1915 rather than 3 years later would have been with the fleet by the end of 1916.

More flight decks could be provided by converting the Courageous class light battle cruisers when they were less advanced or laying them down as “Improved Hermes” class carriers. Ideally they would be completed to the double-hangar design that they were eventually completed to in the real world and as they were built as carriers from the keel up their displacement would be smaller or they could be better ships on the same tonnage.

The problem with this is that I usually have 6 Queen Elisabeth class battleships built instead of the Renown and Courageous classes so that the RN has 4 Hoods and 16 Queen Elisabeths in World War II.

c) Scenario 1909

In the real world the Esher Report of January 1909 decreed that the Royal Navy should develop rigid airships, the British Army should continue its experiments with non-rigid airships and that no work should be done on aeroplanes. Lord Esher soon changed his mind, but the damage had already been done. Had he decreed that aeroplanes were to be developed too and that funds should be provided in the 1909-10 Estimates to build a trials ship, then this would have put the development of aircraft carriers 2 to 2½ vital years ahead of the real world.

The Africa trials would be brought forward to January 1910 or even the second half of 1909. Ark Royal and Hermes would be ready for 1911 or even 1910. The bespoke carrier was ordered in the 1913-14 Estimates (or even 1912-13) for completion at the end of 1914 (or even 1913).

The conversions of Conte Rosso and Gulio Cesare were authorised in August 1914 because they could be completed by the end of 1915 and 3 “Improved Hermes” were ordered in early 1915 instead of the light battle cruisers and completed in the fourth quarter of 1916.

Thus at Jutland the Grand Fleet would have the services of Argus, Gulio Cesare and Hermes rather than Campania, Engadine and Vindex. All other things being equal the converted liners were at Scapa Flow with the main fleet, but one was refitting and the other missed the order to sail and was ordered back to base by Jellicoe after she belatedly sailed. This left Hermes with the battlecruisers because she was faster than the other ships. Unlike Engadine she was able to keep several aircraft in the air at all times. They did not spot the Germans before the light cruisers did, but after that provided the fleet with a continuous stream of sighting reports that gave Jellicoe a much clearer idea of where the enemy was. They were of no use during the night action, but the aeroplanes were airborne again at first light on 1st June and soon found the survivors of the High Seas Fleet heading for the Horns Reef channel. Whether Jellicoe would have been able to catch them up is another matter. The converted liners carried primitive torpedo bombers. Their torpedoes were not powerful enough to sink a battleship, but might be able to slow some down so that the British battleships could catch up and finish them off. However, as neither of them were there this wasn’t an option.

By early 1917 the Grand Fleet would have enough carriers to put 200 aircraft in the air. Therefore there was no need to supplement them with capital ships and cruisers fitted with flying off platforms. It could conduct raids on the German coast in greater strength and better aircraft than the ones that were available in the real world.

In this version of history the earlier invention of the aircraft carrier made the Royal Navy even more air minded that it was in the real world and did all it could to retain control of the RNAS. If unsuccessful it would intensify its efforts after the war to get it back. No battleship was sunk during the Great War in this version of history, but the admirals saw that it was only a matter of time before suitable aircraft were ready and wanted to continue the development of naval aviation, "Regardless of finance or tradition," after the war was over.

There would probably be some more merchant ship conversions in the second half of the war. However, these ships were the first escort carriers, because their job was to defend convoys with anti-submarine aircraft, beyond the range of land based aircraft in the western approaches.

I have the bare bones of a RN pre 1WW TL that has the DNC going the X4 Fast battleship route AFTER Dreadnought and Invincible

Basically they enter WW1 with More and faster battleships but only a handful of Battle Cruisers but more heavy light Cruisers earlier

With another pod giving the RN a heavier than air component earlier I can see a "Float plane Support Cruiser" being developed to support Cruiser Squadrons by operating amphibian Aircraft and then later being adapted as OTL but 3 years earlier to operate fixed wing ---- or something along those line

Basically they enter WW1 with More and faster battleships but only a handful of Battle Cruisers but more heavy light Cruisers earlier

With another pod giving the RN a heavier than air component earlier I can see a "Float plane Support Cruiser" being developed to support Cruiser Squadrons by operating amphibian Aircraft and then later being adapted as OTL but 3 years earlier to operate fixed wing ---- or something along those line

Circa 1910, Blimps were the best choice for naval patrol aircraft. They served the same role as picket ships, warning they the Grand Fleet of approaching enemy vessels.

Blimps were viable long-range patrol aircraft until 1960. The USN flew them over convoys during WW2 and U-boats soon learned that they had to stay submerged - or die - any time WALLY aircraft flew over convoys. It took until 1944 for fixed wing (B-24 Liberator bombers) to close the mid-Atlantic gap. Until 1960, the USN flew a fleet of radar-equipped, blimps to track Russian submarines in the mid-Atlantic Ocean. The mid-Atlantic gap

Was eventually closed by a combination of hydrophones, attack submarines, P-3 patrol planes and satellites.

As for mine-sweeping ... there were a few experiments with blimps pulling mine-sweeping gear. I wonder if blimps had sufficient horsepower to pull mine-sweeping gear into a strong wind.

More recently, heavy helicopters (Sikorsky CH-53 and Mi-17) have worked as mine-sweepers. Heavy-lift helicopters make good mine-sweepers because of their massive engines. CH-53 was developed as an enclosed cabin version of the Sikorsky Skycrane and every successive version has more powerful engines.

If we are speculating, I would like to see a through-deck carrier or angled flight deck much earlier. POD a commercial carrier is converted to an aircraft carrier, but because of space restrictions, she has two elevators installed outboard. The first elevator is amidships on the port side and the second elevator is outboard of the starboard stern. Fear of the crash net/barrier sees pilots "cheating" landings to the port side of the deck.

Airplanes that have just landed-on are man-handled to the starboard side of the forecastle to clear the deck quickly. During a re-fit, her arrestor cables are re-aligned to match the angled landing-deck. Without the do-or-die threat of an arrestor/crash net, pilots' stress levels would reduce when landing-on. As long as you had enough space alongside the landing strip (to secure airplanes that had just landed) you would only need a crash net for emergencies.

Blimps were viable long-range patrol aircraft until 1960. The USN flew them over convoys during WW2 and U-boats soon learned that they had to stay submerged - or die - any time WALLY aircraft flew over convoys. It took until 1944 for fixed wing (B-24 Liberator bombers) to close the mid-Atlantic gap. Until 1960, the USN flew a fleet of radar-equipped, blimps to track Russian submarines in the mid-Atlantic Ocean. The mid-Atlantic gap

Was eventually closed by a combination of hydrophones, attack submarines, P-3 patrol planes and satellites.

As for mine-sweeping ... there were a few experiments with blimps pulling mine-sweeping gear. I wonder if blimps had sufficient horsepower to pull mine-sweeping gear into a strong wind.

More recently, heavy helicopters (Sikorsky CH-53 and Mi-17) have worked as mine-sweepers. Heavy-lift helicopters make good mine-sweepers because of their massive engines. CH-53 was developed as an enclosed cabin version of the Sikorsky Skycrane and every successive version has more powerful engines.

If we are speculating, I would like to see a through-deck carrier or angled flight deck much earlier. POD a commercial carrier is converted to an aircraft carrier, but because of space restrictions, she has two elevators installed outboard. The first elevator is amidships on the port side and the second elevator is outboard of the starboard stern. Fear of the crash net/barrier sees pilots "cheating" landings to the port side of the deck.

Airplanes that have just landed-on are man-handled to the starboard side of the forecastle to clear the deck quickly. During a re-fit, her arrestor cables are re-aligned to match the angled landing-deck. Without the do-or-die threat of an arrestor/crash net, pilots' stress levels would reduce when landing-on. As long as you had enough space alongside the landing strip (to secure airplanes that had just landed) you would only need a crash net for emergencies.

Potential POD's

The Aircraft Carrier Story 1908 – 1945, Guy Robbins

Page 13

Samson duly flew off the forecastle of the old battleship Africa in Sheerness harbour on 10th January 1912. His aeroplane (a Short 538) was equipped with pontoons attached to the wheels for emergency tough-down on the sea. As a result Seuter and Rear Admiral E C T Troubridge, Chief of the War Staff, suggested trials in four cruisers of the Home Fleet before issuing two machines per warship in the fleet. Further experiments involved flying-off from cruiser’s deck at sea and while underway at 10 ½ kts.

Unlike Ely, however, Samson never attempted to follow up these experiments (taking off) by flying onto a ship despite having a technique proposed for doing so. In December 1911 Lieutenant H A Williamson, a submariner, forwarded a proposal to the Admiralty to convert existing warships, or even to build a new carrier, to launch and retrieve aeroplanes for fleet anti-submarine duties. This design was rejected by Samson as too complicated, but primarily because he had decided to develop seaplanes. He considered flying onto a ship too dangerous for fast machines and unnecessary for seaplanes.

The Aircraft Carrier Story 1908 – 1945, Guy Robbins

Page 15

Churchill authorised the conversion of a merchant ship, but sufficient funds were unavailable in the 1912/1913 Estimates and the Treasury refused any extra. Sueter therefore secured permission to prepare the old cruiser Hermes for seaplane experiments and proposed in December, that Beardsmores build a 15kt carrier (a variant of their original design) to pioneer flying (seaplanes) from her deck. She was to become a depot ship for destroyers once she had gained data for the fleet carrier.

The Board refused permission to build her since Churchill had ruled against any more depot ships and they required proof of the feasibility of seaplanes at sea plus further design work due to the invention by Shorts of folding seaplanes. Another factor was that the Air department had already spent £0.5 million on restarting the airship programme.

The Grand Fleet, D K Brown

Page 74

There were several trials between 1903 and 1908 when the Admiralty decided that kites as then known had little to offer – there is a note by Brown ‘It is interesting that the problem of the disturbed air behind the funnels and superstructure was already apparent.’

Page 75

There were two proposals for aviation ships in 1913, Admiral Mark Kerr suggesting a purpose built ‘true’ carrier while the First Sea Lord, Admiral of the Fleet Sir Arthur Wilson, had a less ambitious scheme. He wanted to convert an Eclipse class cruiser, removing the main mast and building a landing platform aft with a take-off platform forward. Special cranes would lift planes from one deck to the other. In the event, an even more limited scheme was adopted – this was the conversion of the cruiser Hermes.

Ader wrote a book on military aviation in 1909 which contained his proposal. Here is the wiki article on the book:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/L'Aviation_Militaire

"L'Aviation Militaire" is especially famous for its precise description of the concept of the modern aircraft carrier with a flat flight deck, an island superstructure, deck elevators and a hangar bay.

On the structure of the aircraft carrier:

"An airplane-carrying vessel is indispensable. These vessels will be constructed on a plan very different from what is currently used. First of all the deck will be cleared of all obstacles. It will be flat, as wide as possible without jeopardizing the nautical lines of the hull, and it will look like a landing field."

—Military Aviation, p35

On stowage:

"Of necessity, the airplanes will be stowed below decks; they would be solidly fixed anchored to their bases, each in its place, so they would not be affected with the pitching and rolling. Access to this lower decks would be by an elevator sufficiently long and wide to hold an airplane with its wings folded. A large, sliding trap would cover the hole in the deck, and it would have waterproof joints, so that neither rain nor seawater, from heavy seas could penetrate below."

—Military Aviation, p36

On the technique of landing:

"The ship will be headed straight into the wind, the stern clear, but a padded bulwark set up forward in case the airplane should run past the stop line"

—Military Aviation, p37

The book received much attention, and the US Naval Attaché in Paris sent a report on his observations, before actual experiments took place in the United States a year later[1]

[FONT="]"L'Aviation Militaire" was translated into English by Lee Kennett under the title "Military Aviation" (for Air University Press, Maxwell Air Force Base Alabama, 2003, ISBN 1-58566-118-X). [/FONT][FONT="]

[/FONT]

The Aircraft Carrier Story 1908 – 1945, Guy Robbins

Page 13

Samson duly flew off the forecastle of the old battleship Africa in Sheerness harbour on 10th January 1912. His aeroplane (a Short 538) was equipped with pontoons attached to the wheels for emergency tough-down on the sea. As a result Seuter and Rear Admiral E C T Troubridge, Chief of the War Staff, suggested trials in four cruisers of the Home Fleet before issuing two machines per warship in the fleet. Further experiments involved flying-off from cruiser’s deck at sea and while underway at 10 ½ kts.

Unlike Ely, however, Samson never attempted to follow up these experiments (taking off) by flying onto a ship despite having a technique proposed for doing so. In December 1911 Lieutenant H A Williamson, a submariner, forwarded a proposal to the Admiralty to convert existing warships, or even to build a new carrier, to launch and retrieve aeroplanes for fleet anti-submarine duties. This design was rejected by Samson as too complicated, but primarily because he had decided to develop seaplanes. He considered flying onto a ship too dangerous for fast machines and unnecessary for seaplanes.

The Aircraft Carrier Story 1908 – 1945, Guy Robbins

Page 15

Churchill authorised the conversion of a merchant ship, but sufficient funds were unavailable in the 1912/1913 Estimates and the Treasury refused any extra. Sueter therefore secured permission to prepare the old cruiser Hermes for seaplane experiments and proposed in December, that Beardsmores build a 15kt carrier (a variant of their original design) to pioneer flying (seaplanes) from her deck. She was to become a depot ship for destroyers once she had gained data for the fleet carrier.

The Board refused permission to build her since Churchill had ruled against any more depot ships and they required proof of the feasibility of seaplanes at sea plus further design work due to the invention by Shorts of folding seaplanes. Another factor was that the Air department had already spent £0.5 million on restarting the airship programme.

The Grand Fleet, D K Brown

Page 74

There were several trials between 1903 and 1908 when the Admiralty decided that kites as then known had little to offer – there is a note by Brown ‘It is interesting that the problem of the disturbed air behind the funnels and superstructure was already apparent.’

Page 75

There were two proposals for aviation ships in 1913, Admiral Mark Kerr suggesting a purpose built ‘true’ carrier while the First Sea Lord, Admiral of the Fleet Sir Arthur Wilson, had a less ambitious scheme. He wanted to convert an Eclipse class cruiser, removing the main mast and building a landing platform aft with a take-off platform forward. Special cranes would lift planes from one deck to the other. In the event, an even more limited scheme was adopted – this was the conversion of the cruiser Hermes.

Ader wrote a book on military aviation in 1909 which contained his proposal. Here is the wiki article on the book:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/L'Aviation_Militaire

"L'Aviation Militaire" is especially famous for its precise description of the concept of the modern aircraft carrier with a flat flight deck, an island superstructure, deck elevators and a hangar bay.

On the structure of the aircraft carrier:

"An airplane-carrying vessel is indispensable. These vessels will be constructed on a plan very different from what is currently used. First of all the deck will be cleared of all obstacles. It will be flat, as wide as possible without jeopardizing the nautical lines of the hull, and it will look like a landing field."

—Military Aviation, p35

On stowage:

"Of necessity, the airplanes will be stowed below decks; they would be solidly fixed anchored to their bases, each in its place, so they would not be affected with the pitching and rolling. Access to this lower decks would be by an elevator sufficiently long and wide to hold an airplane with its wings folded. A large, sliding trap would cover the hole in the deck, and it would have waterproof joints, so that neither rain nor seawater, from heavy seas could penetrate below."

—Military Aviation, p36

On the technique of landing:

"The ship will be headed straight into the wind, the stern clear, but a padded bulwark set up forward in case the airplane should run past the stop line"

—Military Aviation, p37

The book received much attention, and the US Naval Attaché in Paris sent a report on his observations, before actual experiments took place in the United States a year later[1]

[FONT="]"L'Aviation Militaire" was translated into English by Lee Kennett under the title "Military Aviation" (for Air University Press, Maxwell Air Force Base Alabama, 2003, ISBN 1-58566-118-X). [/FONT][FONT="]

[/FONT]

Something I have wondered about a few times is what could have been done with the depot ship Vulcan (probably only seaplanes) or with the Protected Cruisers Powerful and Terrible - Friedman does mention in a footnote that Armoured Cruisers of the Drake class were looked at for potential seaplane carrier conversion.

What I would want to know is - could you trunk the funnels of Powerful/Terrible to one side and put a full length flight deck over a hanger on the existing hull?

What I would want to know is - could you trunk the funnels of Powerful/Terrible to one side and put a full length flight deck over a hanger on the existing hull?

The issue with fast battleships is that nobody had quite understood, by 1914, how useful high speed was going to be; machinery was expensive, the fuel to feed into the machinery was a major factor in the size and cost of the hull of the ship-

in general, the battle line's 21 knots seemed adequate to the task, and only major increases on that- to 25 knots or better- seemed to matter very much; and that could only be achieved at such an increase in size and cost that either corners would have to be cut, elsewhere- battlecruiser armour, ahem-

or no corners cut, in which case the ships involved would be highly expensive and at a severe disadvantage in that they would always be fighting against odds.

Consider; one Admiral class was the cost equivalent of two and a half, more or less, QE class. It does make sense not to push it too far; greater performance was possible, but it rapidly encountered diminishing economic returns- an Admiral, or two, against their cost equivalent in QE's would be a desperately uneven and almost certainly losing fight.

Prewar fast battleships are unlikely, even although they were contemplated, because the disadvantages seemed to outweigh the advantages.

Genuine changes in technology- like the three knots Dreadnought gained over her contemporaries by moving to turbines, or the (intended) four knots the QE's gained over the rest of the dreadnought line by moving to oil firing, yes, by all means, take advantage of that; but just piling on more of the same, overdeveloping existing technology, is a good way to find oneself at odds of five to two against.

In practise, and in the AH I really must get along with, the decisive driver turns out to be torpedoes- a battlecruiser can move quickly and handily enough as to comb torpedo fire and bring her guns to bear in circumstances that a battleship would have to turn away from or accept the probability of being hit. In an odd way Fisher may have been right; speed is armour, at least against that.

The R BC's would be urgently needed primarily to replace losses, though.

Blimps- the Sea Scouts and Coastals had early aero engines, types obsolete in heavier than air aircraft; 75 and 100hp motors in 1917-18, when Rolls-Royce was bringing 200hp fighter and 350hp bomber engines into service.

Now that I pay attention to the numbers, it's unlikely that they could make much headway into the wind, not towing minesweeping gear- and shades of ASDIC, the RN did not think mines were going to be much of a problem in the war in 1914, because they had sweeping technology, it was a solved issue. Oops.

A blimp design based around the Rolls-Royce Eagle or Sunbeam Cossack would be a different beast- possible, but different; but there was ferocious competition for those engines, not least from the heavy bombers.

the surface raider problem turned out to be far less serious than previously expected, and the patrolling cruisers and armed merchant cruisers less urgently required; the northern blockade kept the best and let the rest go for troopships. I would consider those ships to be available, from october-november 1914 anyway; question then becomes of they would be any good.

the extempore carriers- all eleven of them- did serve, to some effect; but seaplane recovery is bloody hard work and leaves a ship hove to in potentially hostile waters for extended periods, so landing on is much safer for the ship, which does argue for a proper flat top.

in general, the battle line's 21 knots seemed adequate to the task, and only major increases on that- to 25 knots or better- seemed to matter very much; and that could only be achieved at such an increase in size and cost that either corners would have to be cut, elsewhere- battlecruiser armour, ahem-

or no corners cut, in which case the ships involved would be highly expensive and at a severe disadvantage in that they would always be fighting against odds.

Consider; one Admiral class was the cost equivalent of two and a half, more or less, QE class. It does make sense not to push it too far; greater performance was possible, but it rapidly encountered diminishing economic returns- an Admiral, or two, against their cost equivalent in QE's would be a desperately uneven and almost certainly losing fight.

Prewar fast battleships are unlikely, even although they were contemplated, because the disadvantages seemed to outweigh the advantages.

Genuine changes in technology- like the three knots Dreadnought gained over her contemporaries by moving to turbines, or the (intended) four knots the QE's gained over the rest of the dreadnought line by moving to oil firing, yes, by all means, take advantage of that; but just piling on more of the same, overdeveloping existing technology, is a good way to find oneself at odds of five to two against.

In practise, and in the AH I really must get along with, the decisive driver turns out to be torpedoes- a battlecruiser can move quickly and handily enough as to comb torpedo fire and bring her guns to bear in circumstances that a battleship would have to turn away from or accept the probability of being hit. In an odd way Fisher may have been right; speed is armour, at least against that.

The R BC's would be urgently needed primarily to replace losses, though.

Blimps- the Sea Scouts and Coastals had early aero engines, types obsolete in heavier than air aircraft; 75 and 100hp motors in 1917-18, when Rolls-Royce was bringing 200hp fighter and 350hp bomber engines into service.

Now that I pay attention to the numbers, it's unlikely that they could make much headway into the wind, not towing minesweeping gear- and shades of ASDIC, the RN did not think mines were going to be much of a problem in the war in 1914, because they had sweeping technology, it was a solved issue. Oops.

A blimp design based around the Rolls-Royce Eagle or Sunbeam Cossack would be a different beast- possible, but different; but there was ferocious competition for those engines, not least from the heavy bombers.

the surface raider problem turned out to be far less serious than previously expected, and the patrolling cruisers and armed merchant cruisers less urgently required; the northern blockade kept the best and let the rest go for troopships. I would consider those ships to be available, from october-november 1914 anyway; question then becomes of they would be any good.

the extempore carriers- all eleven of them- did serve, to some effect; but seaplane recovery is bloody hard work and leaves a ship hove to in potentially hostile waters for extended periods, so landing on is much safer for the ship, which does argue for a proper flat top.

Share: