Chapter I - Calling the Faithful

Here's the first chapter in my new ATL about a more successful second crusade.

Sorry about the amount of OTL stuff in this post, the next will be plenty more AH! Hope you all enjoy!

Chapter One

Calling the Faithful

Ever since the success of the First Crusade in establishing Latin states in Outremer, the Holy Land had found itself under siege as the Moslem rulers fought against these new invaders. With a thinly spread Latin population ruling over a mix of native Christians and Moslems, the crusaders were practically fighting a losing battle, eventually leading to the fall of the capital of the least Latinised of the states, Edessa, in the last days of 1144 to Zengi, ruler of Aleppo and Mosul. The Count of Edessa, Joscelin, had been away from the city with his army at the time, allowing Zengi to push even further west before the crusaders were able to gather and halt his advance.

Although Zengi returned to Mosul, fear spread throughout the crusader states that soon Moslem armies would sweep aside the remains of the County of Edessa, take Antioch and cause the destruction of all that the Latins had fought for. It was this fear that led to Pope Eugene III’s papal bull Quantum Praedecessores, calling Christendom to war once again, promising absolution for those who completed the crusader, either through death or by taking Edessa, and guaranteeing the Church’s protection for the families of the crusaders. Louis VII of France, to whom the papal bull was addressed, had been planning such an expedition already, so as to fulfil a vow his dead brother had made, and was initially reluctant to join the official crusade. However, Bernard of Clairvaux, under orders from the Pope to preach the crusade, convinced Louis to agree to join Eugene’s venture. With this major success in rallying support, Quantum Praedecessores was reissued in 1146 and Bernard set off into Germany to gather further support.

As Bernard travelled, popular support for the Second Crusade began to increase, miracles being attributed to the preacher everywhere he went. More and more people began to take the cross, but with this success and the rise of religious fervour, brutality against the Jews began to spread. Fuelled by the renegade monk Radulphe, who preached that the Jews should be slaughtered, violence began to spiral out of control. Attempts were made by the authorities, both secular and ecclesiastical, to stem the violence, but it was swiftly getting out of hand. Even the Archbishop of Mainz was unable to prevent a mob killing a group of Jews he had taken into his own house to protect. They appealed to Bernard, who issued a strong condemnation of the atrocities, but the continued and so he travelled in person to the areas most affected and preached against the violence, even forcing Radulphe to return to the monastery he had left without permission. With this the violence at last began to subside.

Conrad III of Germany was the next monarch to take the cross, but in his kingdom yet another problem now arose. The Saxons in the north were reluctant to go to the Holy Land when, as they saw it, enemies of Christianity lay at their very doorstep in the form of the pagan Slavs. When the Saxons asked Bernard for official support of their own crusade, their request was rejected in communications from the Pope, who had been convinced of imminent danger to the crusader states by the somewhat exaggerated reports of emissaries from Outremer and so decided that official sanction must focus on the Holy Land in this instance. To the Pope, the Moslems were the greatest danger to Christendom. With coaxing from Bernard, the Saxons would provide men for the crusade, but their numbers were limited in comparison to the contingents from other regions. In Iberia too the request was made of the Pope that official sanction be given to a crusade against the Moors. Despite some slight hesitation, with the entreaties of Alfonso VII of León and Castile this was shortly given.

Sorry about the amount of OTL stuff in this post, the next will be plenty more AH! Hope you all enjoy!

Chapter One

Calling the Faithful

Ever since the success of the First Crusade in establishing Latin states in Outremer, the Holy Land had found itself under siege as the Moslem rulers fought against these new invaders. With a thinly spread Latin population ruling over a mix of native Christians and Moslems, the crusaders were practically fighting a losing battle, eventually leading to the fall of the capital of the least Latinised of the states, Edessa, in the last days of 1144 to Zengi, ruler of Aleppo and Mosul. The Count of Edessa, Joscelin, had been away from the city with his army at the time, allowing Zengi to push even further west before the crusaders were able to gather and halt his advance.

Although Zengi returned to Mosul, fear spread throughout the crusader states that soon Moslem armies would sweep aside the remains of the County of Edessa, take Antioch and cause the destruction of all that the Latins had fought for. It was this fear that led to Pope Eugene III’s papal bull Quantum Praedecessores, calling Christendom to war once again, promising absolution for those who completed the crusader, either through death or by taking Edessa, and guaranteeing the Church’s protection for the families of the crusaders. Louis VII of France, to whom the papal bull was addressed, had been planning such an expedition already, so as to fulfil a vow his dead brother had made, and was initially reluctant to join the official crusade. However, Bernard of Clairvaux, under orders from the Pope to preach the crusade, convinced Louis to agree to join Eugene’s venture. With this major success in rallying support, Quantum Praedecessores was reissued in 1146 and Bernard set off into Germany to gather further support.

As Bernard travelled, popular support for the Second Crusade began to increase, miracles being attributed to the preacher everywhere he went. More and more people began to take the cross, but with this success and the rise of religious fervour, brutality against the Jews began to spread. Fuelled by the renegade monk Radulphe, who preached that the Jews should be slaughtered, violence began to spiral out of control. Attempts were made by the authorities, both secular and ecclesiastical, to stem the violence, but it was swiftly getting out of hand. Even the Archbishop of Mainz was unable to prevent a mob killing a group of Jews he had taken into his own house to protect. They appealed to Bernard, who issued a strong condemnation of the atrocities, but the continued and so he travelled in person to the areas most affected and preached against the violence, even forcing Radulphe to return to the monastery he had left without permission. With this the violence at last began to subside.

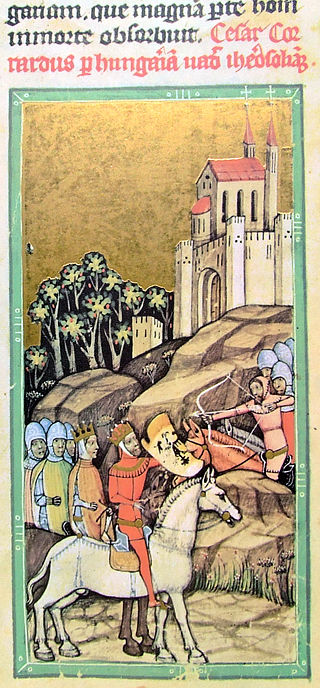

Conrad III of Germany was the next monarch to take the cross, but in his kingdom yet another problem now arose. The Saxons in the north were reluctant to go to the Holy Land when, as they saw it, enemies of Christianity lay at their very doorstep in the form of the pagan Slavs. When the Saxons asked Bernard for official support of their own crusade, their request was rejected in communications from the Pope, who had been convinced of imminent danger to the crusader states by the somewhat exaggerated reports of emissaries from Outremer and so decided that official sanction must focus on the Holy Land in this instance. To the Pope, the Moslems were the greatest danger to Christendom. With coaxing from Bernard, the Saxons would provide men for the crusade, but their numbers were limited in comparison to the contingents from other regions. In Iberia too the request was made of the Pope that official sanction be given to a crusade against the Moors. Despite some slight hesitation, with the entreaties of Alfonso VII of León and Castile this was shortly given.

Last edited: