I wanted to create a TL about the creation of a Jewish Homeland in East Africa that nearly came into fruition. The assassination of Czar Alexander II of Russia would unleash a series of anti-Semitic violence affecting the world's largest Jewish community. The result was a series of violent pogroms, continuing until the 1920s where Jews were stripped of civil rights, robbed of their belongings and in extreme cases killed. These actions would cause 2 million Jews to abandon the Russian Empire between 1881 and 1913, with nearly 75% going to the United States, and others settling in South America, Great Britain, Canada, South Africa, France and other countries.

However, the arrival of destitute and culturally foreign refugees from Russia led to increased anti-Semitism in the West. The Dreyfus Affair in France in 1894, and increasing hostility to Jewish immigrants in England, and other countries led many Jews to push for the establishment of a Jewish homeland, where Jews would be able to govern themselves and maintain their customs, religion and no longer fear persecution. This would result in the Zionist movement, with the goal of creating a Jewish homeland in Palestine.

As the Zionist movement spread amongst Jews in the West, the first Zionist Congress was held between 29 August and 31 August 1897 in Basel Switzerland with the ultimate goal of establishing a Jewish homeland in Ottoman-ruled Palestine. Though a small number of Eastern European Jews had been settling in Palestine since 1882, their numbers were insignificant and by 1900, Jews only constituted 6% of a population of 600,000. However, the Zionist Organization, led by Hungarian-born Theodor Herzl, would continue to meet annually to pursue its goal and was committed to the idea of a Jewish homeland in Israel. To that end, in May 1901, they approached the Ottoman Sultan for a Charter to settle Jews in Palestine, but were rebuffed. Attempts to secure support from Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany seemed promising at first, however his support for the idea was withdrawn once he began to seek an alliance with the Ottomans.

Meanwhile, anti-Semitic persecution increased in Russia, culminating in the Kisinev pogroms in Bessarabia in April 19-20 1903. The violence of these pogroms shocked the western powers, and the British Government was particularly incensed at the barbarity of the violence. The persecution affected what was still the world's largest Jewish community, and would lead many prominent Jews in the West to argue that a Jewish homeland anywhere was better than none. Lord Rothschild, a prominent British Jew wrote to Herzl in 1902 "I must not be a stickler for principles and reject any immediate help for the poorest of our poor, no matter what form it may take".

Arriving in London in October 1902, Herzl met with members of the British cabinet seeking their assistance in establishing a Jewish settlement under British protection. Leopold Greenberg, the head of the British Zionist Federation along with Herzl met with Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain and Foreign Secretary Lord Landsdowne in April 1903. It would be in this meeting that Chamberlain proposed establishing a Jewish settlement in the British East Africa Protectorate. He mentioned that the land between Nairobi and the Mau Escarpment would be ideal, especially the Uasin Gishu Plateau.

The British government had several reasons for wanting to settle British East Africa, besides simply assisting refugees. Firstly, the government had spent over £5 million on the Uganda Railway, and though completed in 1901, little economic benefit had been derived from the railway as fewer than 500 Europeans resided in British East Africa. There was no commercial agriculture to speak of and it was hoped that settlement of the Jews in this sparsely populated territory would spur economic development. Finally, there was growing anti-immigrant hostility in Britain itself, with nearly 100,000 Russian-born Jews living in the country by 1901.

In 4 July 1903, Leopold Greenberg, head of Britain's Zionist Organization had Liberal MP and lawyer David Lloyd George draw up the Articles of Association for the Jewish homeland to be submitted to the British Cabinet for review. The articles called for a constitution to be approved by the British government in a protectorate that was to be "Jewish in character and with a Jewish Governor to be appointed by His Majesty in Council". The charter would grant the settlers complete domestic control of internal affairs over the colony including the power of taxation for administrative matters and all land matters. All settlers would automatically become British subjects, and the settlement was to be named "New Israel" and would be allowed to create its own flag.

On 23 July 1903, the British cabinet began reviewing the Articles submitted by Lloyd George, and agreed to them with some changes. On 6 August, 1903 the cabinet had altered the articles and were ready to submit the legislation to the House of Commons. Though they did agree to a Jewish Commissioner to be appointed by His Majesty the King, they rejected that inhabitants would automatically become British subjects. Settlers would have to reside in the territory for a minimum of two years before being able to become British subjects. In addition, they stipulated that the self-governing protectorate would have a free hand in regard to purely domestic matters and His Majesty's government would still retain control of external affairs.

Herzl felt triumphant and had the backing of many members of Britain's influential Jewish community. In addition, Jews financiers from South Africa, agreed to provide funding for the acquisition of land from the South African-owned East African syndicate for the immediate settlement of Jewish refugees. Herzl would propose his sixth Zionist Congress in Basel on 23-28 August 1903. However, settlement in what was called Uganda would be controversial and Herzl would face bitter opposition by many Zionists who were committed to a Jewish homeland in Palestine.

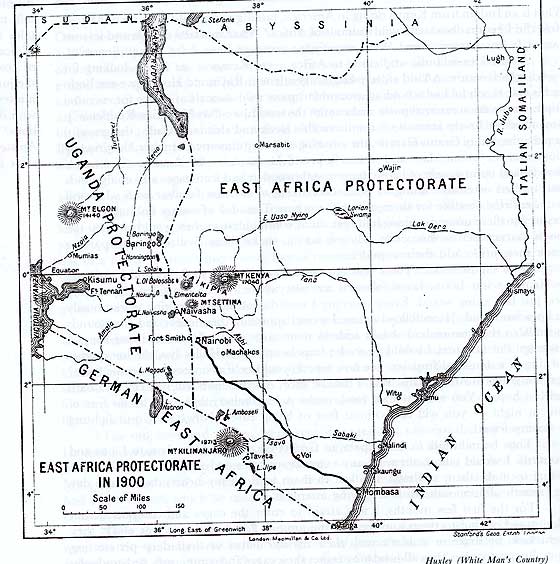

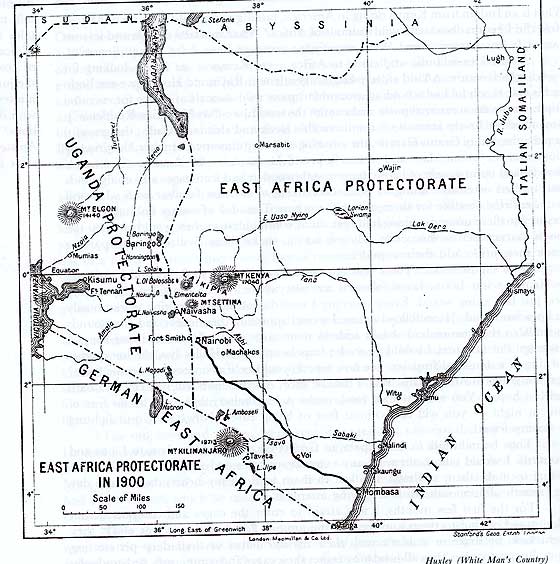

A map of the British East Africa Protectorate in 1900

However, the arrival of destitute and culturally foreign refugees from Russia led to increased anti-Semitism in the West. The Dreyfus Affair in France in 1894, and increasing hostility to Jewish immigrants in England, and other countries led many Jews to push for the establishment of a Jewish homeland, where Jews would be able to govern themselves and maintain their customs, religion and no longer fear persecution. This would result in the Zionist movement, with the goal of creating a Jewish homeland in Palestine.

As the Zionist movement spread amongst Jews in the West, the first Zionist Congress was held between 29 August and 31 August 1897 in Basel Switzerland with the ultimate goal of establishing a Jewish homeland in Ottoman-ruled Palestine. Though a small number of Eastern European Jews had been settling in Palestine since 1882, their numbers were insignificant and by 1900, Jews only constituted 6% of a population of 600,000. However, the Zionist Organization, led by Hungarian-born Theodor Herzl, would continue to meet annually to pursue its goal and was committed to the idea of a Jewish homeland in Israel. To that end, in May 1901, they approached the Ottoman Sultan for a Charter to settle Jews in Palestine, but were rebuffed. Attempts to secure support from Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany seemed promising at first, however his support for the idea was withdrawn once he began to seek an alliance with the Ottomans.

Meanwhile, anti-Semitic persecution increased in Russia, culminating in the Kisinev pogroms in Bessarabia in April 19-20 1903. The violence of these pogroms shocked the western powers, and the British Government was particularly incensed at the barbarity of the violence. The persecution affected what was still the world's largest Jewish community, and would lead many prominent Jews in the West to argue that a Jewish homeland anywhere was better than none. Lord Rothschild, a prominent British Jew wrote to Herzl in 1902 "I must not be a stickler for principles and reject any immediate help for the poorest of our poor, no matter what form it may take".

Arriving in London in October 1902, Herzl met with members of the British cabinet seeking their assistance in establishing a Jewish settlement under British protection. Leopold Greenberg, the head of the British Zionist Federation along with Herzl met with Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain and Foreign Secretary Lord Landsdowne in April 1903. It would be in this meeting that Chamberlain proposed establishing a Jewish settlement in the British East Africa Protectorate. He mentioned that the land between Nairobi and the Mau Escarpment would be ideal, especially the Uasin Gishu Plateau.

The British government had several reasons for wanting to settle British East Africa, besides simply assisting refugees. Firstly, the government had spent over £5 million on the Uganda Railway, and though completed in 1901, little economic benefit had been derived from the railway as fewer than 500 Europeans resided in British East Africa. There was no commercial agriculture to speak of and it was hoped that settlement of the Jews in this sparsely populated territory would spur economic development. Finally, there was growing anti-immigrant hostility in Britain itself, with nearly 100,000 Russian-born Jews living in the country by 1901.

In 4 July 1903, Leopold Greenberg, head of Britain's Zionist Organization had Liberal MP and lawyer David Lloyd George draw up the Articles of Association for the Jewish homeland to be submitted to the British Cabinet for review. The articles called for a constitution to be approved by the British government in a protectorate that was to be "Jewish in character and with a Jewish Governor to be appointed by His Majesty in Council". The charter would grant the settlers complete domestic control of internal affairs over the colony including the power of taxation for administrative matters and all land matters. All settlers would automatically become British subjects, and the settlement was to be named "New Israel" and would be allowed to create its own flag.

On 23 July 1903, the British cabinet began reviewing the Articles submitted by Lloyd George, and agreed to them with some changes. On 6 August, 1903 the cabinet had altered the articles and were ready to submit the legislation to the House of Commons. Though they did agree to a Jewish Commissioner to be appointed by His Majesty the King, they rejected that inhabitants would automatically become British subjects. Settlers would have to reside in the territory for a minimum of two years before being able to become British subjects. In addition, they stipulated that the self-governing protectorate would have a free hand in regard to purely domestic matters and His Majesty's government would still retain control of external affairs.

Herzl felt triumphant and had the backing of many members of Britain's influential Jewish community. In addition, Jews financiers from South Africa, agreed to provide funding for the acquisition of land from the South African-owned East African syndicate for the immediate settlement of Jewish refugees. Herzl would propose his sixth Zionist Congress in Basel on 23-28 August 1903. However, settlement in what was called Uganda would be controversial and Herzl would face bitter opposition by many Zionists who were committed to a Jewish homeland in Palestine.

A map of the British East Africa Protectorate in 1900