James V would depart from Falkland Palace, leaving his wife and infant daughter behind, and moved south calling his nobles to assemble with their men near Dumfries. James had never been popular with his highborn subjects, as was seen in his difficulty assembling an army prior to the Battle of Solway Moss, but the defeat had damaged all of Scotland’s prestige, both the nobles’ and King’s alike. While there were some lords noticeably absent, including the Earl of Arran and several other Protestants, the King commanded an army of much greater size than he had 5 months earlier, with troops under his command close to 25,000. By the beginning of April James and his forces began to move south into England, taking a more easterly route as to avoid reminders for the defeat they had only recently suffered.

In England the news of James’ survival infuriated Henry VIII, and the King’s mood was made only worse by the fact that many of the same nobles who had made pledges to the King had been some of the first to once again take up arms against him. Henry sent several diplomats to James requesting the immediate return of the prisoners which had been accidentally released and had broken their vows. Reportedly James avoided seeing the diplomats himself and remarked that he believe that vows made to heretics did not count. This would only serve to increase the rage Henry felt at his nephew, rage he would take out on several people other than the King of the Scots.

Scandal would rock the court of Henry VIII when Thomas Seymour, an uncle to Henry’s son and the brother of his late wife Jane, married Catherine Parr, a member of the Lady Mary’s household. While Henry VIII had expressed interest in Catherine, and made hints that he wished to marry her, he had become distracted by the war and she had fallen by the wayside and, believing the King no longer wanted to marry her, had married Thomas Seymour in secret. Naturally this was a large scandal as Catherine had only recently been widowed and Henry became determined to punish both Thomas and Catherine, whom he viewed as traitors. The couple was separated and both were placed in the Tower while the King began drawing up charges against them, both were charged with treason alongside adultery (as Henry made it clear he did not view their marriage as valid) and were subsequently sentenced to be beheaded, as was Henry’s common method of removing enemies and opponents in his realm. On the morning of July 12th, 1543 both Catherine and Thomas would be executed.

The doomed bride: Catherine Parr (1512-1543)

During the scandal in the court of Henry, James officially entered England and moved south towards the town of Carlisle, where he would find Thomas Wharton (the commander of the English forces during the Battle of Solway Moss) awaiting him with 7,000 men. Unlike in the past, the Scots were prepared and unified and launched a vicious and merciless attack at the English lines which were unprepared for the surprising level of ferocity. By early afternoon the English retreated and Carlisle was taken by the Scottish army on the morning of June 5th, 1543.

It was widely agreed that the defeat at Carlisle, along with the heartbreak of having Catherine marry Thomas Seymour, was too much for King Henry who fell into a period of illness brought on by stress and depression in June 1543. It was during this time that the King scrapped his plans to invade France, as Scotland remained unconquered and the realm was near bankruptcy, and this infuriated his ally, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V who then decided to negotiate a truce with Francis largely at the behest of the French Queen, and Charles’ sister, Eleanor. The Emperor wished to focus on the Protestants in northern Germany and Francis wished to seek revenge on the English for their alliance with the Hapsburgs. The truce was officially signed in August 1543 and was made with the intent of lasting peace. Charles and Francis both withdrew their conflicting claims over Burgundy and Naples respectively and Francis’ second son Charles was to marry Mary, the daughter of the Emperor.

Henry’s illness grew worse upon hearing that the Emperor had betrayed him and Francis, his onetime ally, was intending to continue the war against England. Rumors abounded that Francis intended to invade England, leading the command himself, and establish James V as the ruler of England alongside Scotland. These whispers grew highly popular among Catholics in the realm, especially in Wales and the north, and forced the dying King to make a clear path of succession. As fall began to approach Parliament was forced to confirm the Act of Succession (1543) declaring that Edward was next in line for the throne and then, should he die without issue, was to be followed by Mary and Elizabeth after her. It was also stipulated in the Act that no descendants of Margaret Tudor would be eligible to inherit the throne. He and Margaret had always had a tense relationship while she was still living (with him having counselled Margaret against divorcing James IV only to then go on to split with the Pope when he wouldn’t grant Henry a divorce) and the King had always favored his younger sister Mary over Margaret. This, combined with the fact he was at war with Margaret’s son, made it an easy choice for the now bedridden and dying Henry. With the succession now clear and James V believed to have been removed from the throne, Henry quietly passed away on November 24th, 1543. It was the one year anniversary of the Battle of Solway Moss, the last time the King had tasted victory. Edward, his son, was hastily crowned Edward VI and the Catholics, led by Bishop Stephen Gardiner (who was named to be an executor of Henry’s will) attempted to seize power back from the Protestants who dominated the King’s regency council. All the while the young Edward was being educated by a devout and fervent Reformer, John Cheke despite the best tries by the Catholics to get a more moderate tutor.

A portrait of an elderly King Henry VIII

With Henry VIII now dead there were numerous issues which arose over how the Church of England was to move forward. The traditionalists, some of which wanted to go entirely back into the Catholic fold, moved boldly within weeks of Henry’s death and formally accused Thomas Cranmer, the Archbishop of Canterbury and one of the leading Protestants in the realm, of heresy. This was meant primarily as a way to stifle further reform of the Church of England and diminish the Protestant hold over the young King, whose own mother had been a Catholic. Opposition arose from the Protestants on the regency council, but mainly from Edward Seymour, the King’s uncle and head of the Protestant faction. After weeks of political maneuvering it became clear that there had been months of plotting by the Catholics who were quite extensive in number. With the King in his minority it initially seemed as though Cranmer was doomed and that the Catholics would have the power and support necessary to get him removed from office. Seymour would move decisively to prevent this however, and in early December took his nephew to one of his estates with his tutor in tow. It was clear that the King was not going to be moved for quite some time. He did this discretely though, and the following week at Hampton Court Gardiner was barred from entering the Council Chambers much to his surprise and anger. Seymour organized a Protestant lead investigation into the extent of the plot and in the meantime bullied the remaining Catholics besides Gardiner into standing down through various methods, primarily bribery and the threat of execution. It was a stunning turn of events which grew even more surprising when Gardiner himself was arrested on the morning of January 4th, 1544 and taken to the Tower of London to be imprisoned. Without a clear leader the Catholic faction in England grew much weaker at court, so much so that the heir to the throne, Henry’s daughter and devout Catholic, Mary withdrew herself to her newly inherited estates. Within two months of the old King’s death the Regency Council had already gained a clear leader in the form of Edward Seymour and the Catholics had seen their position surprisingly reduced.

Both the Catholics and the Protestants on the Regency Council could agree on one thing though, the war had to be ended. The realm was nearly bankrupt and had now tasted defeat following the loss of Carlisle and further Scottish incursions in the north. Diplomats were sent to James V and Francis, both who would consent to peace on their terms. James wished to keep Carlisle, and rule it as had once been done by Scottish Kings prior to him along with the return of his uncle, and onetime host, the Earl of Angus, on whom James wished to take revenge for near imprisonment during his childhood. Francis meanwhile wished for a series of monetary payments be made to him despite the fact that England was nearing a complete lack of funds and even, some whispered, debt. The regency council had no choice but to accept, and the Treaty of Westminster was signed, turning the war from a near Scottish defeat into a victory in nearly an instant. James V returned to Falkland Palace in December and found, as promised, that his wife Marie was indeed pregnant and set to give birth within a couple of weeks. It appeared that the glory James had once had, possessing two sons and prestige worldwide, lost since the Battle of Solway Moss, had once more returned.

Marie went into labor on December 17th, several weeks earlier than expected, and at long last James had another son, conveniently named James. The birth was extremely hard on Marie however, and she was bedridden for several weeks afterward. It was a close call, but she pulled through, although some believed that it meant she was no longer fertile, a charge which she would fervently deny. The boy was baptized into the Catholic faith by Cardinal Beaton and unlike his children in the past, was to be kept near the King in order to, hopefully, secure his survival.

Prince James and his mother, Marie d'Guise (1544)

With the war over, and the threat England posed greatly reduced, the devout James began to work on suppressing Protestantism in Scotland. The Earl of Arran was imprisoned on paper for refusing to join the King in his campaign against England but it was widely accepted that it was a part of James’ disdain for him. Shortly after the King began, with the backing of Parliament, to actively hunt down and imprison Protestant preachers within the realm. This made waves all across Europe as Scotland made it clear that it wanted nothing to do with the increasingly reformed faith in England and instead wished to remain in union with Rome and allied with France. Ironically, despite his professed devotion to the Church, he partially contributed to the increased disillusionment with Catholicism by appointing his illegitimate children, many of whom were exceptionally young, to the various church offices in the realm. This blatant nepotism would come under increased fire in the realm, although the spark could not catch on due to the King’s active persecution of reformers. Seven men were burned at the stake, and numerous more were imprisoned and forced to recant their beliefs.

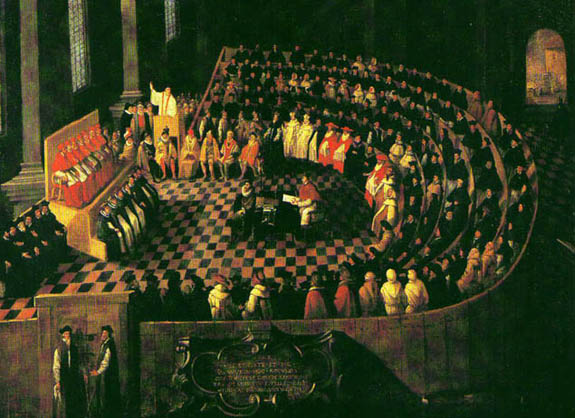

In the meantime across Europe the Pope began to plan and organize the Council of Mantua, which had been long delayed and had been cancelled on several occasions. The primary goal of the council was to reform the church in answer to some of the calls of reform alongside making it much more acceptable as a way to win back Lutherans, Calvinists, and other Protestants. It was now clear that the Reformation was much more than an issue between members of the Church, but instead the early stages in an attempt to formulate separate sects of Christianity, whether intentional or not. Scandinavia, England, and Northern Germany had already begun to convert and there were whispers that Austria, Bohemia, France, and Scotland were not far behind. Furthermore with Charles V announcing he intended to take military action against the Protestants in the Holy Roman Empire now that France had made peace with him, Pope Paul III knew that the Church had to act if It was to retain some influence on ending the Reformation. To allow Charles to solve the problem without assistance from the Church would undermine the position of the papacy and set a precedent, or so Paul believed. Therefore a call to council was enacted on February 18th, 1544.