Fifth Installment

Here comes a little alternate "textbook chapter", for a bit of background information and proportions, so we can discuss plausibility issues, consequences etc. in more detail.

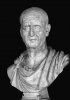

The tyranny of Decius

In 1001 AUC, Pannonia, Moesia and Dacia had come under assault by Goths, Carpi and Vandals. Having scored a victory in battle over a larger group of Carpi, the military tribune of the Legio II Flavia Felix, Pacatianus, was proclaimed Emperor by his soldiers. Emperor Philip the Arab, on the advice of his close ally, Decius, decided to “let the rebellion collapse under its own weight”. Indeed, Pacatianus was faced with both continuing barbarian incursions and a lack of funds, which he attempted to counter by minting more Vimniacan coins, which in turn sped up the devaluation of the currency and drowned the regional economy, creating unrest in the large towns of Sirmium and Naissus.. In 1002, Decius marched towards Moesia with a small force, on Philip`s behest. As soon as word of Decius` arrival at the Istros spread, a group of high-ranking officers and local nobles conspired against Pacatianus and killed him.

In the conspirational alliance against Pacatianus, conflicts over the further course of action erupted almost instantaneously. One group preferred to proclaim Decius as the new Emperor, trusting him to take the threat of Carpian and Gothic invasions seriously and cope with it, while another group feared that further instability in another Roman civil war would expose their lands to barbarian attacks and thus opposed the proclamation.

The “Decian” party prevailed, and Decius was proclaimed Emperor almost immediately upon arrival. Some sources state that Decius protested and refused three times to accept the proclamation. In the light of later events, this appears either unlikely, or a mere show of modesty which had almost become commonplace since the days of Gordian.

Again whether compelled by circumstances or driven by ambition is unclear, Decius or his supporters had a number of those executed who had been purported to him as opponents of his proclamation. Then, he marched towards Italy with the Istrian legions loyal to him.

Decius` and Philips armies met in a valley of the Eastern Alps. The battle was exceedingly bloody, claiming the lives of many thousands of soldiers. But Decius had prevailed and was proclaimed Princeps Augustus and endowed with potestas tribunicia and imperium proconsulare by the Senate in Rome.

Sacrifices, Purges, Plagues and Triumphs: The early reign

Decius knew that his position was unstable. Philip had had a large number of loyal followers among the upper tiers of the Roman oligarchy, only few of whom had fallen in battle. The fate of another usurper, Iotapianus, was unclear so far. It was in this context that Decius issued the fateful decree that everyone in the Empire must sacrifice to the Roman gods, praying for the Emperor to be able to protect the Empire from the barbarians and restitute its order, power, and glory.

Decius started two other initiatives in 1002, too, which are historically overshadowed by his Sacrificing Decree: he began comprehensive repair works of Rome`s infrastructure, and he attempted to reintroduce the office of a Censor, a position in which he hoped to see his associate Valerian. The latter was stalled in 1002 and 1003, though.

The Sacrificing Order led to the largest wave of religious persecution ever occurring in the Roman Empire. Mostly Christians, but also adherents of a number of other small monotheistic religions especially in Syria, were forbidden by the rules of their cults to sacrifice to other deities. Decius` imperial administration executed tens of thousands of citizens in this first wave of persecution (see table below) – among them the loyal and moderate Bishop of Rome, Fabian. Many more Christians fled from the persecution.

Then, a smallpox epidemics broke out, killing people by the thousands every month and causing economic activities and public order to break down. Decius tasked a group of six outstanding medical doctors and high-ranking administrators to deal with this problem – the Sexviri. Based on recommendations from the medical academies of several legions, the Sexviri soon came up with a plan of isolating the infected both within certain quarters of towns, and within quarantined regions. Massive protests from the local administration of various towns prevented the implementation of their plans, though.

Decius himself gathered five legions and confronted an invading army of Goths, Carpi, Vandals and Bastarnae at Nicopolis ad Istrum. The Apollodorian improvements in the defensive structures along the Danube had proven important in decimating the invaders, a task jointly undertaken by the Legio VII Claudia and border auxiliaries before Decius arrived. Nicopolis withstood the siege by the barbarians long enough for Decius to arrive and obtain a decisive victory. Then, Decius set with four legions across the Danube and conducted a punitive campaign against the Carpi, Bastarnae and Goths, killing and enslaving tens of thousands of them at victorious battles at Acidava, on the Oak Plains and at Carsium.

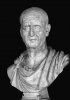

Decius returned to Rome triumphantly. From his strengthened position, he installed Valerian as a very powerful Censor, tasked with reforming fiscal administration and gathering information about the local implementation of quarantine measures and other decrees as well as about who followed which cults and the like.

What may have been intended as “restitutio rei publicae” ended up as tyranny. 1004 AUC was a peaceful year but also one haunted by the smallpox epidemics, and Decius` / Valerian`s structural reforms, which undermined local autonomy, were implemented in many provinces.

They perpetuated the persecution of nonconformist religious groups like Christians and Nazarenes. Though having been dominated by non-aggressive doctrines for centuries, radical groups gained strength within these confessions. Among the Christians, the influential Bishop of Rome, Fabius, had been put to death in the first wave of Decian persecutions already, in late 1002 or early 1003. Under permanent pressure of persecution, the election of new Bishop of Rome, who enjoyed a leading role among Christians, was made impossible throughout 1003 and 1004.

Figure 34: Estimated numbers of Christians fleeing from persecution 1002-1007 AUC (numbers of total Christian population 1000 AUC)

Iberia: 25,000 (600,000)

Gaul, Germania, Britain: 40,000 (700,000)

Italia: 30,000 (800,000)

Sicilia, Sardinia, Corsica: 2,000 (80,000)

Latin Africa: 50,000 (600,000)

Istros Region: 35,000 (450,000)

Aegyptus / Cyrenaica: 60,000 (600,000)

Anatolia & Cyprus: 100,000 (1,350,000)

Greater Syria: 120,000 (1,250,000)

Greek peninsula: 15,000 (300,000)

TOTAL: c. 475,000 (c. 6,750,000)

For figures of killed Christians, see table 35 “Victims of the revolutionary war”

The religious roots of the revolution

By the end of 1004 and the beginning of 1005, three factions had evolved among Christians over the question of how to react to the frequent waves of Decian persecutions:

- a group labeled “Corneliani” supported a continuation of political abstention and non-aggression, rejected millenarian interpretations and posited the theological competence of bishops, deacons and presbyters to absolve penitent “lapsi”

- a second group, which outsiders called “Novatiani” and members called “Cathari”, interpreted the persecutions as signs of a nearing Judgement Day, was neutral (or divided) on the question of political implication and rejected exculpation of lapsi, demanding a full re-baptism

- while a third group, which outsiders called “Theleptians” and members called “Agonistici”, who saw themselves as Cathari, too, and shared the Novatians` millenarianism, openly embraced and organized armed resistance and terrorist attacks against the institutions which persecuted them.

Early in 2005, a secret synod elected Cornelius as Bishop of Rome and leader of the Christians, while a parallel and rivaling synod elected Novatian as Bishop of Rome and leader of the Christians. Upon a new wave of persecution, the Cathari movement broke into two separate groups. The Agonistici of Africa Proconsularis gathered in Thelepte, where they assumed control over the civitas and formed a Council of Saints, which ran both the administration of the town and claimed to represent the true Christendom empire-wide. The Council of Saints gained the support of thousands of rural coloni and slaves by annulling their landowners` rights and titles and conferring them upon councils of the former serfs and slaves. Some sources report about mass baptisms. The Council must also have begun preparations for the defense of the town and its latifundia. Close contacts with radical groups in other civitates were maintained, and soon, the model became widely known.

The African Proconsul had almost no troops at his disposal. Emperor Decius intended to come to his aid and march on Thelepte, when he was informed that the worsening diplomatic relations with Shahanshah Shapur on the Armenian question had finally led to a Sasanian attack on Roman positions in Mesopotamia in 1005 AUC.

Continuation of chapter will be posted soon.