You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

In Soviet Russia, Deck Shuffles You

- Thread starter Maeglin

- Start date

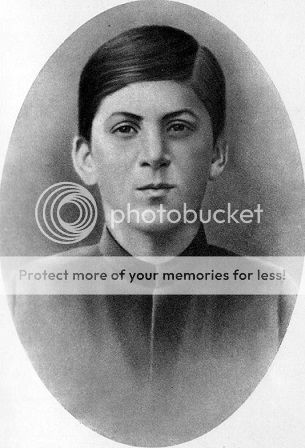

Nikita Khrushchev

1917-1930

The Young Man Who Shook the World

It is impossible to think of the twentieth century without the name Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev. The history of revolutionary socialism, stretching back to Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels and their antecedents, had hitherto been one of abstract theory: the Dictatorship of the Proletariat, stillborn in the Paris Commune, remained tragically out of reach for European revolutionaries. It took a Ukrainan peasant boy and his friend to overturn that convention, and bring the dream of Communism to the huddled masses of the world. Today, nearly one in three human beings lives under a Government directly descended from the regime established by Khrushchev and Kaganovich in those heady months of 1917: a historical legacy of global influence unrivalled since Islam in its first century, and a feat comparable with Alexander the Great himself. For it should never be forgotten that Khrushchev attained power at a mere 23 years of age, and that the other member of that early Communist duumverate, Lazar Kaganovich, was less than a year older. And unlike Alexander, Khrushchev was not born into greatness, but rather rose from the barest poverty of the rural Ukraine. Small wonder, then, that his homeland has affixed his name to everything from cities to lakes, to schools.

Khrushchev was born in 1894, in Kalinovka, and first became acquainted with Marxism through the brother of his parochial school teacher Lydia Shevchenko. While his poor peasant parents could not afford to give him a more elaborate education, the young man devoured the Communist Manifesto and other political texts. He tried, and largely failed, to seek out other like-minded idealists, but was thwarted by both limited opportunities (he spent much of his day as a herdsman), and by the well-founded family fear of the Imperial Government. When his family moved to the city of Yuzovka, however, he found himself an apprenticeship as a metal fitter, and an opportunity for underground political activism in what was then one of the great industrial heartlands of the Empire. It was also there he met the man who would be his lifelong friend and colleague, Lazar Kaganovich.

Khrushchev and Kaganovich were united by the common conviction that Marx's theories could be modified to bring about revolution in Imperial Russia. Rather than waiting for capitalism to collapse through its own decadent excesses and internal contradictions, the idea they came up with was that the course of history could be steered: the apparent feudal apparatus of the Empire could, given the correct leadership, jump directly to a socialist model, bypassing bourgeois capitalist development altogether. Via the publication of the underground Pravda newspaper, the idea took the local Social Democrats by storm, even though some of the more traditional Marxists (to say nothing of Bakunin's anarchists) remained deeply sceptical. During this period, Khrushchev also had his first (minor) run-in with the Tsarist Secret Police, when the regime sought to break a local strike. Khrushchev modified his ideas accordingly: socialism could not triumph by being law abiding and respectful when its opponents were willing and able to use extensive oppression. As he would later say, "if you start throwing hedgehogs under me, I shall throw a couple of porcupines under you."

The collapse of the Tsarist regime in the February Revolution gave Khrushchev and Kaganovich the opening they sought. Even as Alexander Kerensky set up his fragile Provisional Government in Petrograd (formerly St Petersburg), the twain were already seeking to rally the support of workers and peasants for a New Order: as young as they were, they promised a new future, free from the shackles of Russia's despotic past. A particular sore point was the Kerensky Government's determination to continue the war against Germany - Khrushchev, who had narrowly escaped conscription by virtue of his skilled labour status, made a point in every speech of advocating peace. Meanwhile, he and his friend set about organising Worker Governments ('Soviets') in as many cities as they could, in preparation for the day the Proletariat would take control of their own destiny. They also worked closely with the agrarian Social Revolutionaries, pointing out that the peasants and workers shared a common enemy. Before long, the two movements had merged into a populist and somewhat incoherent general protest organisation, with Khrushchev appealing to the farms as much as he did to the factories.

Then in October 1917 (November under the Gregorian calendar) discontent with the Kerensky regime had reached fever pitch. Amid strikes and industrial chaos, and risings in the countryside, Nikita Khrushchev proclaimed the establishment of a new, revolutionary, Russia. Several years later, the country with its diverse nationalities and cultures would be reorganised as a Union of Soviets, the state still known to us today as the Soviet Union.

But the old order was not prepared to die quietly. While the young men were happy enough to bend to Germany's grandiose peace demands, they found themselves fighting a new and much more desperate war: a Civil War between themselves (the Reds) and their anti-Communist opponents (the Whites). While Khrushchev as the new General Secretary took care of Communist Party organisation (much of which had to be delegated), and juggled an awkward set of political alliances, Kaganovich sought to muster military forces from both town and country in support of the Revolution. Fortunately, they were able to find able lieutenants, including the likes of Leon Trotsky, who fascinated the young men with his own interpretation of Marxist theory. Despite minor foreign intervention and general devastation, the Reds finally emerged victorious by 1920.

But leading a Revolution is one thing - actually governing is quite another, and attempting to transform the blasted hulk of Imperial Russia into Socialism is another again. Their peasant allies had been alienated by some of the more desperate food confiscations during the Civil War ("our armies must eat!" cried Kaganovich), despite haphazard attempts at belated compensation, while the outside world saw the new regime as a hotbed of international insurrection.

The Soviet Union in its early days placed greater emphasis on the 'Soviet' than on the 'Union'. Day to day policies were decided democratically and locally by councils of workers and peasants, with Khrushchev himself trying, generally unsuccessfully, to bind these diverse units together into a coherent whole. With different cities and localities deciding on their own road to Socialism, the 1920s was as anticlimactic as it was frustrating for the victorious revolutionaries. What is writing and reading reports in comparison to heroically manning the barricades? Some among the upper ranks of the party hierarchy grumbled that there should be a greater degree of cohesion imposed from above, and that Khrushchev and Kaganovich, despite their achievements and ideas, were simply too young to lead.

Finally, in 1930, Khrushchev informed the Communist Party's ruling committee (the Politburo) that he intended to resign his position as General Secretary. He told them that he felt hurt by the whispering campaign against him, and said that, since older men clearly had greater wisdom than the young, perhaps it was time for a more mature leader.

Last edited:

I have very, very serious doubts about this. Maybe this isn't quite at the Sealion level, but it's close.

First of all, in order to get the February revolution, you need to have WW1 take on a similar course as OTL: Millions of casualties, huge military defeats, gross economic mismanagement, Tsar takes over command at the front and leaves Tsarina home to govern, Tsar fails to reach accomodation with Duma, millions of refugees fleeing the Germans and massive inflation. Absent most (or even all) of these, an anti-tsarist revolution by the liberals and socialists (both within the halls of power and on the street level) will not take place so early.

While this did happen OTL, it also set the stage for coming events, from which its really hard to escape: Liberals govern the country, war effort continues to go badly, as does the economy and inflation, whilst the Soviets expand and grow. However, in order for the bolsheviks to take over the socialist movement and become the armed vanguard of the revolution, they need a major victory and acces to weapons, both provided by the Kornilov affair. IF THIS DOESN'T HAPPEN, then the Soviets will continue to be dominated by the SRs.

Now, a revolution led by the SR's is possible after all. They will push however for free elections (like OTL) and they will win them by huge margins (like OTL). ITTL however, with the Bolsheviks not being the 'armed vanguard of the revolution', they will not be able to shut down the freely elected parliament. This however seems to go against the TL, since you want the Communist Party to win out and not the morderate socialists - therefor, the Communist party needs to break up the SRs by force. In order for it to do so however, it needs to be heavily armed and in control of the secret police (like OTL).

So, we're at a point were the bolsheviks, led by Krushev and Kaganovic, have used force to establish their authority against the SRs via their armed thugs, there's just no way around this. What next though ? They have to fight everyone else - the SRs and the Kadets, the other White armies, the Ukrainians etc etc. In order to do this, they have to maintain order in the cities and field large, mobile armies. Now, you mentioned manning the barricades, which is a sure-fire way to defeat - they need large, mobile forces which they can redirect from place to place, not have immobile garrisons under the control of the local soviets.

This however leeds to the crux of the problem: they CANNOT feed their armies and their cities without resorting to war communism, given that the whole economic system is so fucked up (and you can't say ITTL its different, because then you get no revolution, as explained above). However, resorting to war communism (necessary for their survival) means turning the Soviets in rubber-stamp committees and engaging in wide-spread acts of repression.

This means that this:

cannot happen.

First of all, in order to get the February revolution, you need to have WW1 take on a similar course as OTL: Millions of casualties, huge military defeats, gross economic mismanagement, Tsar takes over command at the front and leaves Tsarina home to govern, Tsar fails to reach accomodation with Duma, millions of refugees fleeing the Germans and massive inflation. Absent most (or even all) of these, an anti-tsarist revolution by the liberals and socialists (both within the halls of power and on the street level) will not take place so early.

While this did happen OTL, it also set the stage for coming events, from which its really hard to escape: Liberals govern the country, war effort continues to go badly, as does the economy and inflation, whilst the Soviets expand and grow. However, in order for the bolsheviks to take over the socialist movement and become the armed vanguard of the revolution, they need a major victory and acces to weapons, both provided by the Kornilov affair. IF THIS DOESN'T HAPPEN, then the Soviets will continue to be dominated by the SRs.

Now, a revolution led by the SR's is possible after all. They will push however for free elections (like OTL) and they will win them by huge margins (like OTL). ITTL however, with the Bolsheviks not being the 'armed vanguard of the revolution', they will not be able to shut down the freely elected parliament. This however seems to go against the TL, since you want the Communist Party to win out and not the morderate socialists - therefor, the Communist party needs to break up the SRs by force. In order for it to do so however, it needs to be heavily armed and in control of the secret police (like OTL).

So, we're at a point were the bolsheviks, led by Krushev and Kaganovic, have used force to establish their authority against the SRs via their armed thugs, there's just no way around this. What next though ? They have to fight everyone else - the SRs and the Kadets, the other White armies, the Ukrainians etc etc. In order to do this, they have to maintain order in the cities and field large, mobile armies. Now, you mentioned manning the barricades, which is a sure-fire way to defeat - they need large, mobile forces which they can redirect from place to place, not have immobile garrisons under the control of the local soviets.

This however leeds to the crux of the problem: they CANNOT feed their armies and their cities without resorting to war communism, given that the whole economic system is so fucked up (and you can't say ITTL its different, because then you get no revolution, as explained above). However, resorting to war communism (necessary for their survival) means turning the Soviets in rubber-stamp committees and engaging in wide-spread acts of repression.

This means that this:

the Soviet Union in its early days placed greater emphasis on the 'Soviet' than on the 'Union'. Day to day policies were decided democratically and locally by councils of workers and peasants, with Khrushchev himself trying, generally unsuccessfully, to bind these diverse units together into a coherent whole. With different cities and localities deciding on their own road to Socialism, the 1920s was as anticlimactic as it was frustrating for the victorious revolutionaries.

cannot happen.

Just to clarify: this is a Shuffling the Deck timeline, which means it is largely intended to be tongue in cheek: the idea is to have all the OTL leaders, but in a completely different order, and generally with completely different personalities and legacies. Hence the handwavium that you would never see in any other setting.

I will rework the first post based off your feedback, though: comedy is better if it is at least plausible.

I will rework the first post based off your feedback, though: comedy is better if it is at least plausible.

Cook

Banned

Nikita Khrushchev

The story of his Premiership will shortly be made into a Hollywood film starring Christian Slater:

Vladimir Ulyanov

1930-1932

Russia's Forgotten Leader

In marked contrast to his illustrious predecessor, you will find few monuments in the Soviet Union dedicated to Vladmir Ilyich Ulyanov. Trapped as he was between the twin glories of the October Revolution and the Great Patriotic War, he presided over little memorable, and if he is remembered at all in modern-day Russia, it is as "the one with the beard and waistcoat", or even as a sort of Soviet Millard Fillmore, famous for being obscure. While some Western historians have recently begun to reassess his contribution to the Soviet state, he has been the subject of few specialised biographies, and much of what follows is still subject to conjecture. Perhaps it is only inevitable that a dry law lecturer in a suit, on the wrong side of 60 years old, should attract less attention than a 23 year old who captured an Empire.

Ulyanov was born in 1870 to a wealthy middle-class family in Simbirsk, and by all accounts spent a happy childhood, playing chess and excelling at school. A few of his chess games survive, and given the evident level of tactical understanding involved, it has been suggested by at least one historian that the world made a tragic mistake in trading a first-rate chess master for a second-rate politician. Ulyanov followed his brother to Kazan State University, where he pursued a degree in law. His grades, again, suggest an excellent student, but his conventionality was such that when his brother Aleksandr became involved in a radical political group on campus, Vladimir wrote a letter home to his mother about it. Aleksandr was forced to disassociate himself from the group, on pain of having his allowance cut off.

It was during his University years that Ulyanov first encountered the works of Georgi Plekhanov, a leading Russian Marxist. Ulyanov had always been a great reader, being particularly fond of the poetry of Gleb Uspensky, but Plekhanov's theories about Russia changing from feudalism into capitalism evidently struck a chord. His mother owned a small estate, so Ulyanov spent several summers in the countryside, collecting social data on the peasantry. We only know this, however, because the resulting paper 'New Economic Developments in Peasant Life' was published in a liberal journal. Had the journal rejected him, it is likely that this period of his life would be a complete blank.

The First World War found Ulyanov lecturing in law at the University of St Petersburg (soon to be Petrograd). Accounts from his students reveal a man who knew his subject area, but who was also prone to overtly dry analysis. He retained an interest in politics, being a card-carrying member of the Russian Social Democratic Party, though this mixture of radicalism with a respectable middle-class persona was a source of amusement to his colleagues. One of them remarked "Vladimir Ilyich is so revolutionary that when confronted with a Do Not Walk on the Grass sign, he will always keep to the pavement."

Nevertheless, it was his ability to analyse complex theory and his undoubted organisational skills that pulled him up the hierarchy of the revolutionary state. Intelligent, disciplined, inoffensive, and always willing to settle disputes over a quiet game of chess, he was the sort of hard-working, middle-aged, middle-class underling the new regime needed. He achieved Politburo status in 1924, and in marked contrast to the likes of Trotsky, managed to balance both intellectualism with a conspicuous lack of self aggrandisement. While there were few words of praise from his colleagues, there were even fewer words of criticism, and he never at any point got himself involved in the whispering campaign against Khrushchev. So when Khrushchev unexpectedly resigned in 1930, it was felt that Ulyanov would make a harmless replacement.

It must have therefore come as a surprise when, as the newly installed General Secretary, he proposed overhauling the Soviet system with what he termed a New Economic Policy: a much more centralised state, combined with small-scale private enterprise. The intent was to achieve what Ulyanov considered to be the best of both worlds: a greater sense of political cohesion, combined with a level of local responsiveness and creativity. 'Market Socialism', he tried to call it, though his critics immediately condemned him for a throwback to capitalism. Much was made of Ulyanov's bourgeois background, to the point that the General Secretary felt every bit as victimised as his predecessor. After fruitlessly trying to push his agenda through the leadership for eighteen months, he finally gave up. Nothing had changed, nothing had happened: the system, as he saw it, was unable to be salvaged. Not even the apparent collapse of global capitalism could cheer him up.

In 1932 he resigned from the General Secretary position and returned to academia.

Last edited:

I am buckled up and in for the ride. I did think the opening post was slightly too similar to OTL's course of events, but I can tell we're going to be diverging quite a lot from now on.

My money is on Stalin being a powerless figurehead in his late 70s, who only 'rules' for a couple of years. Lenin next, as a bookish bureaucrat perhaps? (EDIT: Ninja'd!)

Keep it up.

Also, the spinoffs we predicted have finally come to fruition:

My money is on Stalin being a powerless figurehead in his late 70s, who only 'rules' for a couple of years. Lenin next, as a bookish bureaucrat perhaps? (EDIT: Ninja'd!)

Keep it up.

Also, the spinoffs we predicted have finally come to fruition:

(OOC: this one goes into overt satire more than the previous).

If Nikita Khrushchev created the Soviet Union and Real Existing Socialism, Georgy Maximilianovich Malenkov, its longest-serving leader, is the man who defined it. Not only did he save his country during its darkest hour, but he proved once and for all that one catches more flies with honey than with vinegar. The portly, cuddly, multi-chinned Soviet leader was as popular in the West as he was at home, to the extent that it was openly suggested prior to the 1948 US Presidential election that the Constitution be amended to permit Malenkov to run for the American Presidency. Needless to say, had Malenkov been available to stand in foreign elections, he would have run his competition close, such was his affable charm and intelligence. It is easy to imagine some calculating despot seizing the reins after Ulyanov's short and ill-fated tenure, doing irreparable harm both to the reputation of the Soviet Union and to international Communism; as it was, Communism never has had a better advertisement.

Malenkov was born in Orenburg in 1902, the son of a wealthy farmer. He pursued his studies diligently, except when called out by his father to help sell the harvest. In his spare time, he proved to be an avid reader, and he delighted in the company of others with similar tastes, to the extent that he would often recommend books to people he had barely met. There are several accounts from British diplomats in the 1940s and 1950s, describing how Malenkov defused heated diplomatic incidents through judicious and irreverent literary analysis. His interest in literature and academia brought him into the circle of Vladmir Ulyanov in the early 1920s, and it was Ulyanov who provided Malenkov with both a gateway into politics, and an unexpected opportunity to climb the Soviet ladder. His place in the Politburo was assured in the late 1920s, after an encounter with Khrushchev. The latter appreciated another fresh and youthful voice among a sea of middle-aged faces, and remarked that Malenkov had a knack for language and diplomacy that he himself lacked. Malenkov and the retired Khrushchev remained the best of friends until the latter's death in 1971.

With the resignation of Ulyanov in 1932, the 30 year old Malenkov seemed a return to the Khrushchev era. But it turned out that Malenkov really did have an unexpected talent for Machiavellian politics hitherto lacking among the Soviet leadership. He curried favour with Nikolai Yezhov, the head of the Soviet internal security service, leading the latter to think that the NKVD would have increased responsibilities under a Malenkov regime. Once Yezhov had been lured into showing Malenkov the paperwork for a proposed general purge, Malenkov promptly had the NKVD chief arrested and removed. This episode is, however, cautionary in that it shows what might have happened under a less scrupulous leader.

In terms of economics, Malenkov realised early on that both the traditional Soviet model and Ulyanov's proposed N.E.P. were doomed to failure. Cohesion was needed, but neither could a return to capitalism be justified, especially as the forces of bourgeois liberalism appeared in retreat on every front. Malenkov's plan was to Plan. Replacing the vast array of small localised workers councils with elected regional Soviets, and a Supreme Soviet in Petrograd, he set the representatives to work on concocting multi-year quotas for production. Malenkov used his best diplomatic talents to argue in favour of this model, and set his friends in academia to work in figuring out how to include pricing mechanisms into the system. He did not get everything he wanted, but few could argue that the Malenkov reforms were not a significant improvement on what went before. A much greater emphasis was placed on building up Soviet heavy industry, and providing materials for the Red Army.

It was, however, in the nick of time. The countries bordering the Soviet Union still, as of the 1930s, took a dim view of the intentions of the revolutionary government in Petrograd. Believing that the Red Army was something of a paper tiger, some even made territorial demands of Russia: a small military might still make mincemeat of "peasants with pitchforks" if they had the secret support of Berlin. Malenkov rejected their demands out of hand. He was greeted with a joint invasion of the Soviet Union by a coalition of Poland, Finland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, the Baltic States, and Nazi Germany. Amid chaotic scenes, Malenkov had no choice but to move the capital back to Moscow.

It was the war years that solidified Malenkov's reputation in the West. At almost one stroke, the Soviet leader had gone from the piggish monster of Anglo-American propaganda (George Orwell's Animal Farm being a particularly low blow in this regard, poking fun at Malenkov's weight) to loveable, cuddly Uncle George. Uncle George, however, always made a point of giving credit to others, especially the ever loyal and ever victorious Commander Zhukov. The Great Patriotic War was tough and brutal, but Malenkov never flinched from urging his people forward to victory. His controversial decision in the late 1930s to ignore calls for a purge of "disloyal" officers probably helped the Soviet cause too.

Malenkov finally retired in 1953, stating that over 20 years in office was enough for anyone. He might have reconsidered his choice within a few years, given the nature of his successor.

Georgy Malenkov

1932-1953

Uncle George: Beloved and Respected

Uncle George: Beloved and Respected

If Nikita Khrushchev created the Soviet Union and Real Existing Socialism, Georgy Maximilianovich Malenkov, its longest-serving leader, is the man who defined it. Not only did he save his country during its darkest hour, but he proved once and for all that one catches more flies with honey than with vinegar. The portly, cuddly, multi-chinned Soviet leader was as popular in the West as he was at home, to the extent that it was openly suggested prior to the 1948 US Presidential election that the Constitution be amended to permit Malenkov to run for the American Presidency. Needless to say, had Malenkov been available to stand in foreign elections, he would have run his competition close, such was his affable charm and intelligence. It is easy to imagine some calculating despot seizing the reins after Ulyanov's short and ill-fated tenure, doing irreparable harm both to the reputation of the Soviet Union and to international Communism; as it was, Communism never has had a better advertisement.

Malenkov was born in Orenburg in 1902, the son of a wealthy farmer. He pursued his studies diligently, except when called out by his father to help sell the harvest. In his spare time, he proved to be an avid reader, and he delighted in the company of others with similar tastes, to the extent that he would often recommend books to people he had barely met. There are several accounts from British diplomats in the 1940s and 1950s, describing how Malenkov defused heated diplomatic incidents through judicious and irreverent literary analysis. His interest in literature and academia brought him into the circle of Vladmir Ulyanov in the early 1920s, and it was Ulyanov who provided Malenkov with both a gateway into politics, and an unexpected opportunity to climb the Soviet ladder. His place in the Politburo was assured in the late 1920s, after an encounter with Khrushchev. The latter appreciated another fresh and youthful voice among a sea of middle-aged faces, and remarked that Malenkov had a knack for language and diplomacy that he himself lacked. Malenkov and the retired Khrushchev remained the best of friends until the latter's death in 1971.

With the resignation of Ulyanov in 1932, the 30 year old Malenkov seemed a return to the Khrushchev era. But it turned out that Malenkov really did have an unexpected talent for Machiavellian politics hitherto lacking among the Soviet leadership. He curried favour with Nikolai Yezhov, the head of the Soviet internal security service, leading the latter to think that the NKVD would have increased responsibilities under a Malenkov regime. Once Yezhov had been lured into showing Malenkov the paperwork for a proposed general purge, Malenkov promptly had the NKVD chief arrested and removed. This episode is, however, cautionary in that it shows what might have happened under a less scrupulous leader.

In terms of economics, Malenkov realised early on that both the traditional Soviet model and Ulyanov's proposed N.E.P. were doomed to failure. Cohesion was needed, but neither could a return to capitalism be justified, especially as the forces of bourgeois liberalism appeared in retreat on every front. Malenkov's plan was to Plan. Replacing the vast array of small localised workers councils with elected regional Soviets, and a Supreme Soviet in Petrograd, he set the representatives to work on concocting multi-year quotas for production. Malenkov used his best diplomatic talents to argue in favour of this model, and set his friends in academia to work in figuring out how to include pricing mechanisms into the system. He did not get everything he wanted, but few could argue that the Malenkov reforms were not a significant improvement on what went before. A much greater emphasis was placed on building up Soviet heavy industry, and providing materials for the Red Army.

It was, however, in the nick of time. The countries bordering the Soviet Union still, as of the 1930s, took a dim view of the intentions of the revolutionary government in Petrograd. Believing that the Red Army was something of a paper tiger, some even made territorial demands of Russia: a small military might still make mincemeat of "peasants with pitchforks" if they had the secret support of Berlin. Malenkov rejected their demands out of hand. He was greeted with a joint invasion of the Soviet Union by a coalition of Poland, Finland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, the Baltic States, and Nazi Germany. Amid chaotic scenes, Malenkov had no choice but to move the capital back to Moscow.

It was the war years that solidified Malenkov's reputation in the West. At almost one stroke, the Soviet leader had gone from the piggish monster of Anglo-American propaganda (George Orwell's Animal Farm being a particularly low blow in this regard, poking fun at Malenkov's weight) to loveable, cuddly Uncle George. Uncle George, however, always made a point of giving credit to others, especially the ever loyal and ever victorious Commander Zhukov. The Great Patriotic War was tough and brutal, but Malenkov never flinched from urging his people forward to victory. His controversial decision in the late 1930s to ignore calls for a purge of "disloyal" officers probably helped the Soviet cause too.

Malenkov finally retired in 1953, stating that over 20 years in office was enough for anyone. He might have reconsidered his choice within a few years, given the nature of his successor.

Last edited:

I'm hoping really hard for Evil Lev Kamenev/Rozenfeld, but I don't think that's going to happen.

I'm hoping really hard for Evil Lev Kamenev/Rozenfeld, but I don't think that's going to happen.

Give it time. We haven't had Stalin yet.

It is nice to see a TL that doesn't just go "more democratic Russian revolution - we all win!" and then ends.

Looking forward to what you do with the rest of your cards.

fasquardon

Looking forward to what you do with the rest of your cards.

fasquardon

Ioseb dze Jughashvili

1953-1954

The Red Priest

There has probably never been a leader anywhere quite like Ioseb dze Jughashvili. It remains one of history's truly unbelievable twists: an elderly Orthodox Patriarch managed to become the General Secretary of a party officially devoted to atheism, and maintain power for a full year, all the while speaking in a near-incomprehensible Georgian accent. What is clear, however, is that the Year of the Priest, as it remains called in the Soviet Union, represented an upsurge of religious fundamentalism unseen in Europe since the height of Martin Luther's Reformation. His successors would ever after baulk at referencing him by name, and indeed throughout the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, there was an active campaign in suppressing his legacy among the people: his teachings were labelled a heretical mistake, and it was often repeated that the true path to Socialism lay elsewhere. His divisive legacy is even seen among overseas Communist Parties. Having reached their heyday in the early 1950s, under the benevolent influence of Uncle George, the Year of the Priest resulted in panic among secular authorities and the active marginalisation of Western Communists. The first signs of a Sino-Soviet split began to appear during this era too, with the new leadership in Beijing unable to accept the overtly Christian message coming from Moscow.

Ioseb dze Jughashvili was born in 1878 in Gori, Georgia, and was the son of an abusive, alcoholic cobbler. Dze Jughashvili remained close to his devoutly religious mother, who believed him destined for great things; she enrolled him in a religious school over her husband's objections. In 1894, Ioseb then received a scholarship to attend the Georgian Orthodox Tiflis Spiritual Seminary. He passed his final exams in 1899 with top marks, and accordingly entered the Orthodox Priesthood. Between his ruminations on faith and human existence, he was also an avid reader of (translated) Goethe and Shakespeare, and adored the Georgian epic, The Knight in the Panther's Skin. He also wrote poetry, some of which has a cult following in the Soviet Union to this day, and it is likely that if dze Jughashvili had not entered the Priesthood, he would have become a novelist or a poet.

The Georgian Orthodox Church re-established its autonomy in the wake of the 1917 Revolution. Admiring his literary bent, and his outspoken defence of the Church, he found favour with the religious authorities, and began to find himself rising up the ranks, becoming a metropolitan bishop in 1930. He was noted as an effective (if somewhat strict) administrator, affectionately nicknamed Bishop Card Index by those under his care. These organisational skills served him well during the war years, where he attracted a enthusiastic and occasionally fanatical following for his powerful speeches. He urged Georgians to work ever harder, to join the Red Army, to supply more textiles and munitions for the great cause. By 1945, he had risen to the top of the Church hierarchy, becoming Catholicos-Patriarch of All Georgia. Notwithstanding their official commitment to atheism, the local party authorities made a point of consulting him on nearly all day-to-day affairs.

Then, in early 1953, the 74 year old Patriarch experienced a vision, a vision of a nation reborn. With a handful of his loyal followers, he resolved to walk barefoot from Georgia to Moscow, to share his revelations with the leaders in the Kremlin. Along the way, others joined in, until by the time the elderly dze Jughashvili reached his destination, he commanded a multitude, consisting of all ages and all backgrounds. Georgy Malenkov had, only several weeks before, announced his retirement, and there was still no clear leader available on hand to greet the arrivals. Indeed, there was great indecision among the Politburo about what, if anything, should be done about them. Lev Kamenev and Leon Trotsky, elderly hardliners that they were, suggested that the crowds be forcibly dispersed: for was not religion the opium of the people? Kamenev and Trotsky were, however, overruled: the majority insisted that the Soviet Union would always recognise an individual's right to assemble peacefully.

When news of the vacant leadership reached dze Jughashvili's followers, they began vocally suggesting that their beloved Patriarch should be appointed to the position. Unthinkable as it was to the more conventional in the party, the Politburo invited him to discuss his vision for the country. Two hours later, he emerged from the meeting, not only having been granted life membership of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, but having been made its new General Secretary too. Western journalists who were on hand to witness the event wrote excitedly of Moscow's new Red Priest. The Year of the Priest had begun.

Ioseb dze Jughashvili started off by telling Soviet citizens that the calamities of war and invasion had been a sign from God that He was displeased with the devotion of His people. The people of the Soviet Union, nay Europe, nay the world, would need to be purified of decadence, and return to the simple faith and life of their fathers. More specifically, the teachings of the Church would become the highest law in the land, and the current multi-year plan would immediately switch from building dams and canals to churches and religious schools. Henceforth, every town in the country would have at least one church, though during the Year of the Priest, there was an active competition among regions to see who could erect the greatest number of religious buildings. Dze Jughashvili is reported to have been delighted by this pious competition.

Nor did he neglect more worldly concerns. The Red Army was subjected to compulsory daily prayers as part of their routine. Dze Jughashvili was immensely proud of his country's military, comparing the clear strength of the Orthodox Church to that of his Catholic counterpart in Rome. "The Pope?" he is said to have remarked, "how many divisions has he got?"

But given the holy nature of Ioseb dze Jughashvili, it was perhaps inevitable that he become a martyr. Not everyone in the Communist Party was happy with their Red Priest, preferring their orthodoxy to be of the lower-case variety. The discontent was fanned by the leader's trusting-yet-arrogant expectation that everyone would simply do their duty without question, and by the annoyance of subjecting the army to daily prayers. In a country supposedly devoted to the teachings of Marx, it was clearly a reactionary throwback. So it was that a small handful of Politburo members plotted to assassinate the General Secretary: Kamenev, Trotsky, and Lavrentiy Beria. In July 1954, as Ioseb dze Jughashvili sat down to his austere dinner, the three of them waited with prepared weapons. Kamenev and Beria had guns, but Trotsky had been unable to find one, so had borrowed an ice pick from a mountaineer friend.

"I forgive you," said the General Secretary, shortly before the pick entered his skull. "God shall not."

Last edited:

Share: